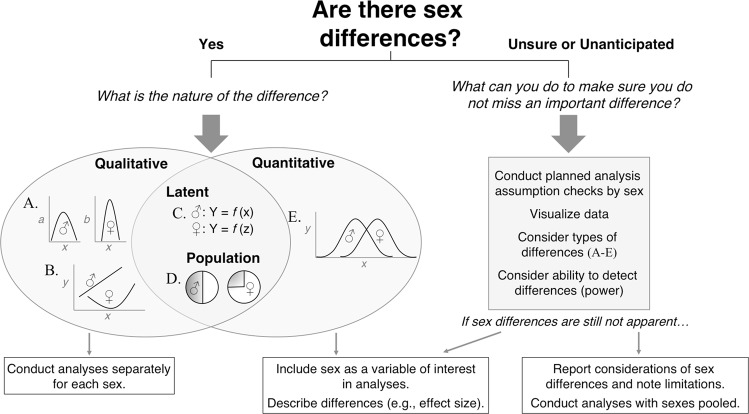

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of questions to ask, possible answers, and suggested analysis aproaches when examining empirical data from male and female subjects. Although informed by the broader literature, responses to questions should be made with respect to the particular data set being analyzed. If a sex difference is expected or present (“Yes”), then the nature of the difference will influence the type of analysis to be conducted. Qualitative differences, in which different traits are examined in the sexes (“A”) or in which the functional form of a relation varies by sex (“B”), require analyses to be conducted separately for males and females; that is, data should be analyzed as if the males and females are from two independent experiments. Quantitative differences, in which males and females show the same pattern of traits, but to different levels, extents, or degrees (“E”), indicate analyses that include sex as a variable of interest (e.g., using sex as a term in a factorial analysis). Latent differences mark sex differences in the mechanisms underlying a trait (“C”), and population differences reflect sex differences in the prevalence of different, non-overlapping traits (“D”). Both can be evaluated in analyses conducted separately by sex, or by including sex as a variable of interest in planned analyses; the decision depends upon the research question, and whether the specific difference of interest is qualitative or quantitative. Thus, a given behavior can reflect multiple types of sex differences. In addition to specifying the statistical significance of sex differences, it is also important to describe their direction and practical importance (e.g., effect size, such as Cohen’s d or percent difference). If it is unclear whether a sex difference is present or not (“Unsure or Unanticipated”), then sex should be included in all assumption checks performed on the data prior to conducting inferential analyses; this may include consideration of all types of differences (“A” thru “E”) with descriptive statistics (e.g., distributions), variance and normality evaluations by sex, and data visualizations (e.g., scatterplots). The sequence and nature of these checks may differ by data set, and may also be done prior to analyzing data in which sex differences are expected. Results can then guide the response to the initial question (i.e., “What can you do to make sure you do not miss an important difference?”). If still unsure whether there are sex differences, then sex can be included as a variable of interest in planned analyses, with the knowledge that analyses will only capture quantitative and some latent and population differences, or analyses may pool subjects across sex. When pooling subjects, effect size should be considered in addition to statistical power, as samples may be too small to detect differences even if they are present (although increases in sample size required to examine main and even interaction effects of sex are modest; see [5]). It may also be important to note when examinations of sex differences are incomplete (e.g., if all types of differences were not studied) or inconclusive (e.g., if power was limited to detect effects).We do not recommend controlling for gender or sex differences as these are non-random differences [8]. Other types of analyses may require examination of individual differences in addition to sex differences [9–12]. See Table 2 for more information.