Abstract

Background

As transcatheter aortic valve replacement expands to younger and/or lower risk patients, the long‐term consequences of permanent pacemaker implantation are a concern. Pacemaker dependency and impact have not been methodically assessed in transcatheter aortic valve replacement trials. We report the incidence and predictors of pacemaker implantation and pacemaker dependency after transcatheter aortic valve replacement with the Lotus valve.

Methods and Results

A total of 912 patients with high/extreme surgical risk and symptomatic aortic stenosis were randomized 2:1 (Lotus:CoreValve) in REPRISE III (The Repositionable Percutaneous Replacement of Stenotic Aortic Valve through Implantation of Lotus Valve System—Randomized Clinical Evaluation) trial. Systematic assessment of pacemaker dependency was pre‐specified in the trial design. Pacemaker implantation within 30 days was more frequent with Lotus than CoreValve. By multivariable analysis, predictors of pacemaker implantation included baseline right bundle branch block and depth of implantation; diabetes mellitus was also a predictor with Lotus. No association between new pacemaker implantation and clinical outcomes was found. Pacemaker dependency was dynamic (30 days: 43%; 1 year: 50%) and not consistent for individual patients over time. Predictors of pacemaker dependency at 30 days included baseline right bundle branch block, female sex, and depth of implantation. No differences in mortality or stroke were found between patients who were pacemaker dependent or not at 30 days. Rehospitalization was higher in patients who were not pacemaker dependent versus patients without a pacemaker or those who were dependent.

Conclusions

Pacemaker implantation was not associated with adverse clinical outcomes. Most patients with a new pacemaker at 30 days were not dependent at 1 year. Mortality and stroke were similar between patients with or without pacemaker dependency and patients without a pacemaker.

Clinical Trial Registration

URL: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/. Unique identifier NCT02202434.

Keywords: aortic valve stenosis, pacemaker dependency, permanent pacemaker, transcatheter aortic valve replacement

Subject Categories: Aortic Valve Replacement/Transcather Aortic Valve Implantation, Pacemaker

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Patients with a pre‐existing permanent pacemaker were at the highest risk of death and no association was found between new pacemaker implantation and worse clinical outcomes; risks for new pacemaker implantation at 30 days following transcatheter aortic valve replacement included baseline right bundle branch block, depth of valve implantation, and medically treated diabetes mellitus.

A prospective, systematic approach to evaluate pacemaker dependency was used; 1‐year mortality and stroke were similar between patients in the pacemaker dependent and not dependent groups compared with patients without a pacemaker.

Predictors of pacemaker dependency at 30 days included right bundle branch block, female sex, and mean depth of implantation and at 1 year included right bundle branch block and left ventricular outflow tract overstretch.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Patients with pre‐existing pacemakers and with baseline conduction disturbances (including right bundle branch block) should be carefully monitored after undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Despite the rapid adoption of transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) for the treatment of aortic stenosis, the high frequency of conduction disturbances and subsequent requirement for permanent pacemaker remains a challenge. Because of the proximity of the aortic annulus with the atrioventricular conduction system, replacement of the aortic valve may result in bundle branch block or high degree atrioventricular block, with consequent permanent pacemaker implantation.1 A lack of consensus or specific guidelines for pacemaker implantation after TAVR have led to wide variation in implantation patterns.2, 3 TAVR‐related conduction system injury/inflammation is dynamic and may resolve over time but the incidence of pacemaker dependency over the course of follow‐up has been poorly studied. Although long‐term pacemaker dependency rates of 27% to 68% following TAVR have been reported, these studies have not systematically assessed pacemaker dependency using a consistent protocol‐driven algorithm. Finally, data regarding the impact of pacemaker implantation and dependency on left ventricular function, arrhythmias, and survival are limited and could influence expansion of TAVR into younger, low‐surgical risk cohorts.

REPRISE III (The Repositionable Percutaneous Replacement of Stenotic Aortic Valve through Implantation of Lotus Valve System—Randomized Clinical Evaluation) is the first large‐scale randomized comparison of 2 different TAVR platforms: the Lotus mechanically‐expanded valve and the CoreValve self‐expanding bioprosthesis.4 Systematic assessment of pacemaker dependency using a defined algorithm was pre‐specified in the trial design.

We report the incidence, timing, and predictors for pacemaker requirement to 30 days after TAVR. Further, we evaluated the proportion of patients who were pacemaker dependent after TAVR as well as predictors and long‐term clinical impact of pacemaker dependency.

Methods

Additional methods can be found in Data S1.

Study Population

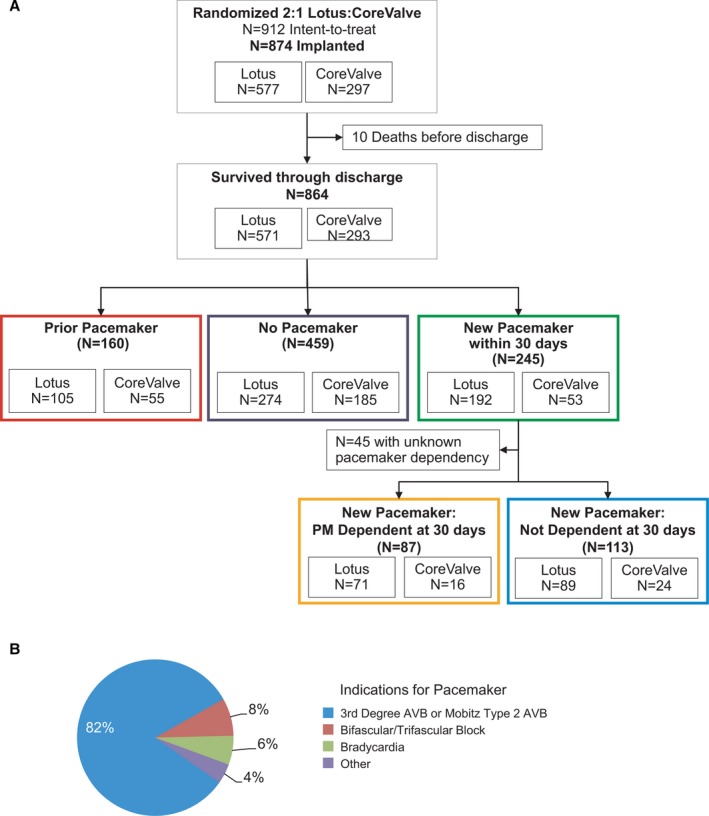

The design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and primary results of the REPRISE III trial have been reported.4 Patients with symptomatic aortic stenosis and Society of Thoracic Surgeons predicted risk of mortality ≥8% or another indicator of high or extreme risk were eligible for enrollment. Patients were randomized 2:1 to Lotus (Boston Scientific Corporation, Marlborough, MA) or CoreValve (CoreValve Classic or EvolutR; Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland).4 Study flow is shown in Figure 1A.4 The protocol was approved by institutional review boards at each site; all patients provided written informed consent. The data for this clinical trial may be made available to other researchers in accordance with the Boston Scientific Data Sharing Policy (http://www.bostonscientific.com/en-US/data-sharing-requests.html). For the current analysis, patients who were randomized and received the assigned valve were included (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Patient flow and pacemaker indications. A, Patient flow. B, Other/unknown indications: 6 other, 5 left bundle branch block, 3 second degree atrioventricular block type 1 and 1 first degree atrioventricular block. AVB indicates atrioventricular block

Pacemaker Dependency Algorithm

At 30 days and 1 year, patients with a new permanent pacemaker were evaluated for dependence via pacemaker interrogation using a pre‐specified algorithm (Figure S1). Pacing rate was decreased by 10 beats per minute (bpm) until: (1) observation of native rhythm; (2) symptom onset; or (3) 30 bpm was reached. Pacemaker dependent patients were defined as patients who were symptomatic or did not have a native rhythm. The percentage of paced ventricular beats was captured.

Definitions

Clinical outcomes were based on the Valve Academic Research Consortium end points5 and were analyzed between 31 days and 1 year to avoid bias stemming from patients not receiving a pacemaker because of early death. An independent core laboratory analyzed all echocardiograms. Health status was assessed by the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Quality of Life and the short form 12 (SF‐12) health survey questionnaires.

Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables are expressed as mean±SD and compared with the Student t test. Discrete variables were reported as n (%), differences were assessed using chi‐square or Fisher exact tests. Time‐to‐event analyses were performed using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared with the log‐rank test. Odds ratios and 95% CI for the adjusted risk of receiving a pacemaker after TAVR or being pacemaker dependent were generated using multivariate logistic regression. Parameters entered in the multivariate model included demographics (sex, age, body mass index), medical history (history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass graft surgery, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation or flutter, stroke, transient ischemic attack, carotid artery stenosis/endarterectomy/stenting, severe liver disease/cirrhosis, renal failure, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, prior balloon aortic valvuloplasty, or current immunosuppressive therapy), Society of Thoracic Surgeons Score, baseline conduction disturbances (right bundle branch block [RBBB], left bundle branch block [LBBB], left anterior fascicular block, first degree atrioventricular block), procedural and echocardiographic characteristics (valve type [Lotus, CoreValve Classic, EvolutR], depth of implantation, left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) and annulus overstretch, valve area, annulus area, mean aortic valve gradient, aortic valve area, LVOT area, and left ventricular ejection fraction <40%, coronary cusp calcification), and baseline laboratory values (serum albumin, platelet count, and serum creatinine). Parameters with a univariate P<0.2 were modeled in a multivariate analysis using a stepwise procedure in a logistic regression model. The significance level thresholds for entry and exit of independent variables into the multivariate model was set at 0.1. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS software, version 9.2 or later.

Results

A total of 912 patients with high/extreme surgical risk and severe, symptomatic aortic stenosis were randomized (2:1, Lotus:CoreValve) and 874 received the assigned device (577 Lotus, 297 CoreValve; Figure 1A). The first‐generation Lotus was used throughout the study while the second‐generation EvolutR was introduced during study enrollment leading to 51.5% (153/297) CoreValve Classic and 48.5% (144/297) EvolutR.

Pre‐existing pacemakers were present in 18% of Lotus patients (105/571) and 19% of CoreValve patients (55/293). In patients who survived through discharge (n=864), the need for pacemaker implantation within 30 days was greater with Lotus than CoreValve among pacemaker naïve patients (Lotus 34% [192/571] and CoreValve 18% [53/293], P<0.001). The 30‐day pacemaker implantation rate in patients treated with CoreValve Classic (20%) and EvolutR (16%) were not significantly different; therefore, patients were analyzed together in the ‘CoreValve’ cohort. Median time to pacemaker implantation was 2 days post‐TAVR; 90% were implanted within 1 week. More than 80% received a pacemaker because of high degree atrioventricular block (Figure 1B).

Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1 and Table S1. Patients who received a new pacemaker within 30 days had higher weight and body mass index and were more likely to have baseline RBBB and hyperlipidemia compared with patients who did not. Depth of valve implantation was greater whereas left ventricular ejection fraction <40%, effective orifice area and overstretch were lower in patients who received a new pacemaker versus those who did not (Table 1). Patients who had a pacemaker before the index procedure were older and had more comorbidities (higher EuroSCORE, increased history of coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, prior myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention, atrial flutter/fibrillation, and left ventricular ejection fraction <40%) compared with patients without a pacemaker.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics in Patients Who Received a New Pacemaker Within 30 days of the Index Procedure

| No Pacemaker (n=459) | New Pacemaker (n=245) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 82±8 | 83±7 | 0.48 |

| Female sex | 236 (51) | 123 (50) | 0.76 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29±7 | 31±8 | 0.001 |

| STS score | 6.5±4.2 | 6.8±3.6 | 0.33 |

| EuroSCORE II | 5.9±4.5 | 6.5±5.7 | 0.14 |

| Extreme surgical risk | 111 (24) | 45 (18) | 0.08 |

| LVEF <40% | 40 (8.8) | 11 (4.5) | 0.04 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 124 (27) | 78 (32) | 0.18 |

| Atrial flutter | 14 (3.1) | 11 (4.6) | 0.31 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 136 (30) | 82 (34) | 0.29 |

| History of coronary artery disease | 321 (70) | 176 (72) | 0.63 |

| History of myocardial infarction | 75 (17) | 44 (18) | 0.54 |

| History of percutaneous coronary intervention | 138 (30) | 79 (32) | 0.55 |

| History of coronary artery bypass graft surgery | 110 (24) | 60 (25) | 0.85 |

| Congestive heart failure | 349 (77) | 182 (76) | 0.80 |

| Annulus area, mm2 | 446±68 | 450±67 | 0.45 |

| LVOT area, mm2 | 427±80 | 427±76 | 0.99 |

| Aortic valve area, cm2 | 0.7±0.2 | 0.7±0.2 | 0.001 |

| Mean aortic valve gradient, mm Hg | 45±14 | 45±13 | 0.77 |

| Baseline RBBB | 17 (3.7) | 68 (28) | <0.0001 |

| Baseline LBBB | 36 (7.9) | 20 (8.2) | 0.91 |

| Baseline LAFB | 70 (15) | 51 (21) | 0.07 |

| Baseline first degree atrioventricular block | 31 (6.8) | 25 (10) | 0.11 |

| Mean depth of valve implantation, mm | 5.7±2.2 | 6.2±2.3 | 0.01 |

| Annulus overstretch | 125±20 | 118±17 | <0.0001 |

| LVOT overstretch | 132±26 | 126±22 | 0.002 |

| Current immunosuppressive therapy | 48 (11) | 22 (9.1) | 0.57 |

| Hypertension | 420 (92) | 231 (94) | 0.18 |

| Prior balloon aortic valvuloplasty | 28 (6.1) | 17 (7.1) | 0.63 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (≥moderate) | 71 (16) | 50 (21) | 0.08 |

| Prior stroke | 60 (13) | 28 (12) | 0.54 |

| Right carotid artery stenosis (≥80%) | 11 (3.0) | 3 (1.6) | 0.40 |

| Left carotid artery stenosis (≥80%) | 9 (2.5) | 2 (1.1) | 0.35 |

| Prior carotid endarterectomy/ carotid artery stenting | 37 (8.2) | 16 (6.6) | 0.47 |

| History of peripheral vascular disease | 127 (28) | 72 (30) | 0.58 |

| History of dialysis‐dependent renal failure | 5 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 0.17 |

| Severe liver disease/cirrhosis | 6 (1.3) | 4 (1.7) | 0.74 |

| Platelet count <150 (109/L) | 81 (18) | 45 (18) | 0.34 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 1.1±0.40 | 1.1±0.42 | 0.64 |

| Serum albumin, g/dL | 3.8±0.43 | 3.8±0.48 | 0.55 |

| Moderate or greater calcification of left coronary cusp | 86 (19) | 46 (19) | 0.20 |

| Moderate or greater calcification of right coronary cusp | 13 (2.8) | 4 (1.6) | >0.99 |

| Moderate or greater calcification of non‐coronary cusp | 331 (72) | 173 (71) | 0.79 |

| Depth of implant from left coronary sinus, mm | 6.3±2.5 | 6.7±2.6 | 0.02 |

| Depth of implant from posterior aortic sinus of the ascending aorta, mm | 5.1±2.7 | 5.7±2.8 | 0.03 |

% unless indicated. Calcification graded by computed tomographic imaging core laboratory as none/mild, moderate, or severe. Annulus overstretch indicates valve area/annulus area [by CTA]; LAFB, left anterior fascicular block; LBBB, left bundle branch block; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVOT overstretch, valve area/LVOT area [by CTA]; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; RBBB, right bundle branch block; STS, Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

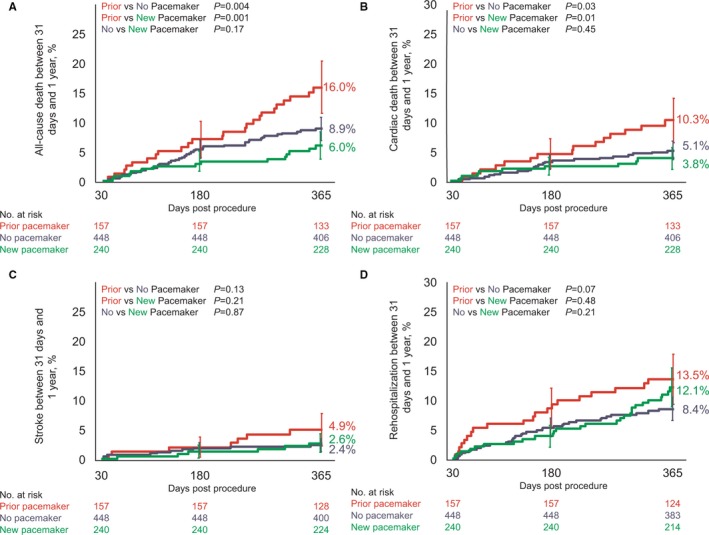

Outcomes in Patients With a New Pacemaker

Patients with a pre‐existing pacemaker had higher clinical event rates than patients who did or did not receive a pacemaker (death: prior pacemaker 15.3% versus no pacemaker 8.7%; P=0.02; versus new pacemaker 5.8%, P=0.002, Table S2). Comparing patients without a pacemaker to those who received a new pacemaker, the frequency of death and stroke between 31 days and 1 year were similar (Figure 2, Table S2). Rates of re‐hospitalization and other clinical outcomes were also similar in patient without and with a new pacemaker (Table S2). Left ventricular ejection fraction was slightly lower in patients who received a pacemaker (1 year: 54±10) compared with those who did not (57±11, P=0.004; Table 3). Both new and no pacemaker patients experienced significant improvements in health status post‐TAVR as measured by the KCCQ (Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire) (Figure S2). The extent of improvement in the physical composite score of the short form 12 (SF‐12) health survey was somewhat smaller in patients who received a new pacemaker compared with those without a pacemaker (3.9 versus 5.4, P=0.08).

Figure 2.

Clinical impact of pacemaker implantation. A, all‐cause death, (B) cardiac death, (C) all stroke, and (D) hospitalization for valve‐related symptoms/worsening congestive heart failure (New York Heart Association class III/IV) in patients with a prior pacemaker at baseline (red), patients who did not receive a pacemaker (purple), and patients who received a pacemaker within 30 days of the index procedure (green). Event rates between 31 and 365 days were calculated with Kaplan–Meier methods. Error bars indicate standard error. AVB indicates atrioventricular block

Table 3.

Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction Over Time Stratified by Pacemaker Status at 30 days

| Pacemaker Status | 30 D | 6 Mo | 1 Y |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prior pacemaker | 52±11 (119)a | 54±11 (97) | 52±11 (91)a |

| No pacemaker | 55±11 (344) | 56±11 (298) | 57±11 (288) |

| New pacemaker | |||

| Overall | 54±11 (194) | 54±11 (172)a | 54±10 (167)a |

| Not dependent | 54±10 (96) | 54±11 (81) | 53±10 (77) |

| Dependent | 53±12 (67) | 53±12 (61) | 53±11 (63) |

The “Overall pacemaker” group included patients without pacemaker dependency information. Dependency was measured at 30 days.

P<0.05 vs the no pacemaker group.

Predictors of Pacemaker Requirement

Valve type was a significant predictor of 30‐day pacemaker requirement overall. The independent multivariate predictors of 30‐day pacemaker implantation in the Lotus and CoreValve cohorts are shown in Table 2 (and Tables S3 and S4). Baseline RBBB was the strongest predictor of pacemaker implantation in both Lotus and CoreValve‐treated patients; mean depth of valve implantation was also a significant predictor. Medically treated diabetes mellitus was associated with an increased likelihood of pacemaker implantation in Lotus‐treated patients.

Table 2.

Multivariate Predictors of 30‐Day Pacemaker Implantation

| Lotus Patients | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| RBBB at baseline | 21.6 (8.3– 56.6) | <0.0001 |

| Mean depth of valve implantation | 1.17 (1.04–1.32) | 0.008 |

| Medically treated diabetes mellitus | 1.66 (1.03–2.67) | 0.04 |

| CoreValve patients | ||

| RBBB at baseline | 5.42 (1.89–15.6) | 0.002 |

| Mean depth of valve implantation | 1.15 (1.01–1.32) | 0.04 |

Included patients who did or did not receive a new pacemaker within 30 days of the index procedure (excluded patients with a prior pacemaker) and analyzed in each treatment group (Lotus or CoreValve). RBBB indicates right bundle branch block.

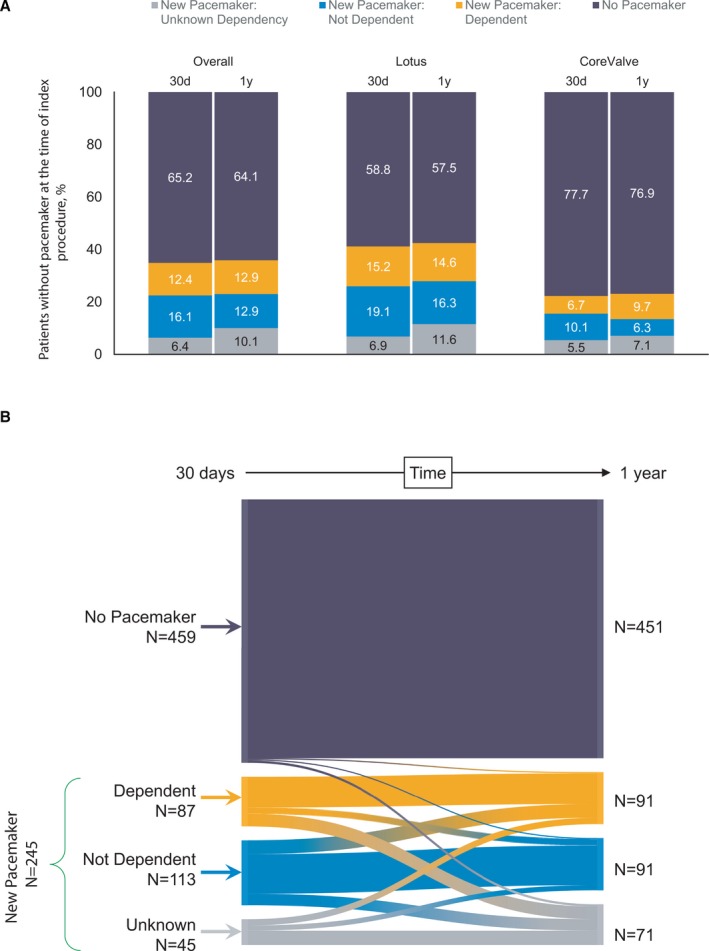

Incidence of Pacemaker Dependency

In patients who received a new pacemaker, the percentage of ventricular paced beats was 65% at 30 days and 57% at 1 year (Table S5). Of the patients without a preexisting pacemaker at baseline, 35% (n=245) received a pacemaker and 65% (n=459) did not receive a pacemaker within 30 days of the index procedure (Figure 3A). At 30 days, 40% of new pacemaker patients who had dependency data were considered dependent based on the pre‐specified algorithm (n=87); at 1 year 50% of these patients were pacemaker dependent (Figure 3A). Approximately 83% of dependent patients at 30 days remained dependent at 1 year; 17% were no longer dependent. Of patients who received a new pacemaker but were not dependent at 30 days, three‐quarters remained that way while one‐quarter became dependent by 1 year (Figure 3B). A break down by valve type is shown in Figure S3.

Figure 3.

Pacemaker dependency at 30 days and 1 year. A, Pacemaker status and dependency in patients who did not have a prior pacemaker at baseline. B, Change in pacemaker status and dependency between 30 days and 1 year.

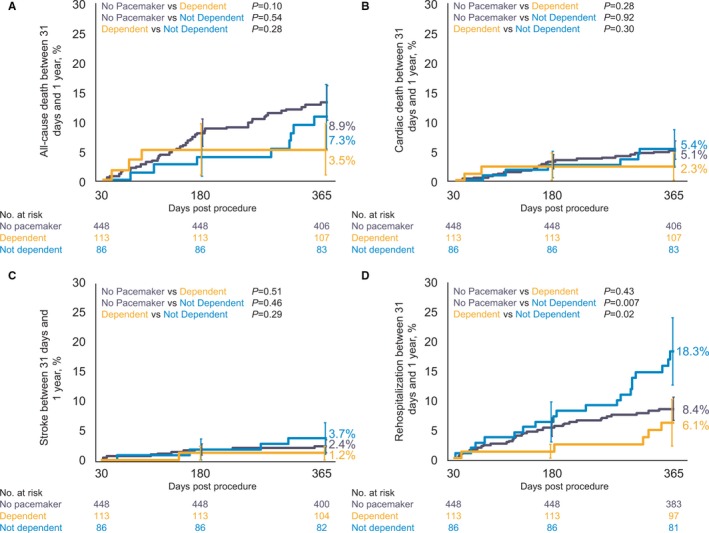

Outcomes by Pacemaker Dependency

No differences in death or stroke between 31 days and 1 year were observed among the no pacemaker, dependent, and not dependent cohorts (Figure 4, Table S6). Patients who received a new pacemaker but were not dependent had higher re‐hospitalization rates (18.3%) compared with patients who did not receive a pacemaker (8.4%; P=0.007) or were dependent (6.1%, P=0.02). The rate of bleeding was higher in patients without a pacemaker (6.0%) compared with patients who received a new pacemaker but were not dependent (0.9%; P=0.02); pacemaker dependent patients had a bleeding rate of 5.8% (Table S6). Left ventricular ejection fraction was similar between patients who were or were not pacemaker dependent (Table 3).

Figure 4.

Clinical impact of pacemaker dependency. A, All‐cause death, (B) cardiac death, (C) all stroke, and (D) hospitalization for valve‐related symptoms/worsening congestive heart failure (New York Heart Association class III/IV) in patients without a pacemaker at baseline (purple) and in patients who received a pacemaker within 30 days of the index procedure who were pacemaker dependent (orange) or not pacemaker dependent (blue) at 30 days. Event rates between 31 and 365 days were calculated with Kaplan–Meier methods. Error bars indicate standard error.

Predictors of Pacemaker Dependency

Multivariate predictors of pacemaker dependency at 30 days included baseline RBBB and depth of valve implantation; male sex was protective (Table 4; Table S7). Baseline RBBB and LVOT overstretch were significant multivariate predictors of pacemaker dependency at 1 year (Table 4; Table S8). Valve type was not a significant predictor of pacemaker dependency in patients who received a pacemaker at either timepoint.

Table 4.

Multivariate Predictors of Pacemaker Dependency

| 30 D | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| RBBB at baseline | 4.47 (2.11– 9.5) | <0.0001 |

| Male sex | 0.39 (0.19–0.78) | 0.008 |

| Mean depth of valve implantation, mm | 1.18 (1.01–1.38) | 0.03 |

| 1 y | ||

| RBBB at baseline | 3.46 (1.70–7.06) | 0.0006 |

| LVOT overstretcha (%) | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | 0.005 |

Included patients who received a new pacemaker within 30 days of the index procedure (excluded patients with a prior pacemaker). LVOT indicates left ventricular outflow tract; RBBB, right bundle branch block.

Valve area/LVOT area [by CTA].

Discussion

The major findings of our study include: (1) patients with pre‐existing pacemakers were at highest risk of death post‐TAVR; new pacemaker implantation was not associated with worse 1‐year outcomes. (2) Multivariate predictors of new pacemaker implantation included baseline RBBB and depth of valve implantation; diabetes mellitus was a predictor for Lotus. (3) Pacemaker dependency was dynamic; 20% to 25% of new pacemaker patients switched dependency status between 30 days and 1 year. (4) Pacemaker dependent patients did not have worse clinical outcomes at 1 year compared with patients without a pacemaker. (5) Pacemaker dependency at both time points was predicted by baseline RBBB; depth of valve implantation and female sex predicted 30‐day dependency whereas LVOT overstretch predicted 1‐year dependency.

Pacemaker implantation post‐TAVR occurs in 2% to 50% of patients depending on valve type, patient population, and other factors.1, 2 Rates in patients treated with the first‐generation Lotus valve range between 25% and 41%.6, 7, 8 The first‐generation Lotus frame may travel deeper into the LVOT during implantation than other valves; subsequent studies using optimized implantation depth and newer versions of the Lotus device suggest lower rates of pacemaker implantation are achievable.8, 9 The most consistent independent predictor of new pacemaker implantation, unrelated to device, is pre‐existing RBBB which is associated with poorer clinical outcomes.10 Depth of valve implantation was a significant predictor of pacemaker implantation in this population as well. Other factors which increase the likelihood of receiving a pacemaker after TAVR can be grouped into pre‐existing conduction abnormalities and anatomic factors (LBBB, annulus/LVOT calcification), procedural factors (overstretch, diameter), and clinical characteristics or demographics.11

Most studies have shown no significant association between post‐TAVR pacemaker implantation and death.1, 12, 13 Two exceptions are the Society of Thoracic Surgeons/ACC (American College of Cardiology) Transcatheter Valve Therapy registry which found 1‐year overall mortality was increased among patients who received a pacemaker after TAVR and there was a trend toward increased mortality at 5 years in the Nordic Aortic Valve Intervention trial (new pacemaker 38.2% versus no pacemaker 21.7%; P=0.07).14, 15 In our study, implantation of a new pacemaker was not associated with adverse outcomes compared with patients who did not receive a pacemaker and, in fact, was associated with numerically fewer adverse outcomes to 1 year. Patients with a pacemaker before TAVR had a higher mortality rate compared with patients who never received a pacemaker. Implantation of a pacemaker post‐TAVR has also been shown to increase hospital length of stay, rehospitalization rates, and be associated with less improvement in left ventricular function.16 Finally, there are complications and financial considerations related to the pacemaker itself.1, 12, 13, 16 These results are primarily derived from higher risk populations; the clinical consequences of new pacemaker implantation in lower risk patients has been less well studied.

Pacemaker dependency post‐TAVR has not been rigorously or consistently evaluated. Conduction disturbances after TAVR may resolve over time; between one‐ and two‐thirds of patients who require a permanent pacemaker after TAVR are not dependent at subsequent follow‐up.7, 17, 18, 19, 20 In REPRISE III, 38% were pacemaker dependent at 30 days and 44% were dependent at 1 year, which is within the wide range observed in other studies (27% and 68%).7, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 The change in dependency during follow‐up underscores the possibility that some conduction disturbances may improve or progress with time. There may be differences among TAVR valves though additional studies are needed to better assess this.

Previous studies have found a number of independent predictors for long‐term pacemaker dependence including pre‐existing RBBB, first‐degree atrioventricular block, left anterior hemiblock, porcelain aorta, and implantation depth of the prosthesis.17, 20, 24, 25 RBBB and depth of implantation were confirmed as independent predictors of pacemaker dependency with LVOT overstretch identified as an additional predictor in the REPRISE III patient population. Male sex was associated with a decreased likelihood of pacemaker dependency.

We found no differences in mortality or stroke between patients who were or were not dependent on the new pacemaker. Few studies have reported outcomes in these patient groups. One small single‐center study showed similar rates of clinical outcomes between dependent and not dependent patients through 1‐year post‐TAVR.17 The rate of rehospitalization was lowest in pacemaker dependent patients compared with patients without a pacemaker or those who were not dependent. The findings related to pacemaker dependency do not necessarily support changing the indication for permanent pacemaker implantation after TAVR, but predictors of short‐term or persistent pacemaker dependency may help in selecting patients who would benefit most from receiving a pacemaker. Techniques or devices that help with short‐term pacing or diagnosis of arrhythmic events, including implantable cardiac monitors,26 could help ensure the optimal use and best outcomes of permanent pacemaker implantation. Our results support periodic examination and adjustment of pacemaker settings to ensure normal conduction while minimizing the risks of long‐term pacing and associated left ventricular dysfunction. Leadless pacemakers and permanent His bundle pacing may contribute to less morbidity in these patients in the future.27, 28

This current study has limitations. The control arm included 2 generations of CoreValve. The study was not designed or powered to compare clinical outcomes in patients with and without a pacemaker. Additionally, atrial fibrillation burden was not prospectively documented by protocol and invasive electrophysiological tests were not performed. Pacemaker dependency is likely to be dynamic and was assessed at only 2 time points and the small number of patients did not allow an analysis of pacemaker dependency by valve type. As such, intervening moments of pacemaker dependency may have been missed. Follow‐up beyond 1‐year is not yet available.

Conclusions

Patients with a pre‐existing permanent pacemaker were at the highest risk of adverse clinical outcomes. No associations between new pacemaker implantation and clinical outcomes were found. Most patients with a new pacemaker were not dependent at 1 year. Pacemaker dependent patients did not have worse outcomes compared with either those without pacemaker dependency or patients without a pacemaker.

Sources of Funding

This work was funded by the Boston Scientific Corporation.

Disclosures

Dr Meduri reports membership on the advisory boards of Boston Scientific and Mitralign, consulting fees from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, and Mitralign, and research grants from Medtronic and Edwards Life Sciences, fees for proctoring for Edwards Life Sciences, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, and Mitralign. Dr Kereiakes reports research grants from Boston Scientific and Edwards Life Sciences and membership on the Boston Scientific Advisory Board. Dr Rajagopal reports membership on the Boston Scientific Advisory Board, speaker/proctoring fees from Medtronic, Edwards Life Sciences, and Abbott. Dr O'Hair reports consultant fees from Medtronic. Dr Linke reports speaker/consultant fees from Medtronic, St. Jude Medical, Claret Medical, Boston Scientific, Edwards Life Sciences, Symetis, Bard, and stock options from Claret Medical. Dr Waksman reports research support/consultant/honoraria from Boston Scientific, Biotronik, Biosensors, Medtronic, Abbott, Symetis, Med Alliance, LifeTech, Amgen, and Volcano/Philips. Dr Stoler reports Medtronic and Boston Scientific advisory board membership and proctor fees from Boston Scientific. Dr Mishkel reports minor honorarium/travel expenses for provision of proctoring services during the trial from Boston Scientific. Dr Schindler reports consultant fees from Boston Scientific and proctor fees from Edwards Life Sciences. Drs Allocco and Meredith are full‐time employee and stockholders at Boston Scientific. Dr Feldman reports research grants from Boston Scientific, Abbott, Edwards Life Sciences, WL Gore, and minor honorarium/travel expenses for provision of proctoring services during the trial from Boston Scientific (and from Abbott, Edwards, WL Gore, outside the submitted work); he is now an employee at Edwards Lifesciences. Dr Reardon reports consulting fees paid to his institution from Medtronic. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Data S1. Supplemental Methods.

Table S1. Additional Baseline Characteristics by Pacemaker Status at 30 Days

Table S2. Outcomes Between 31 Days and 1 Year in Patients Who Had a Prior Pacemaker, no Pacemaker or New Pacemaker at 30 Days

Table S3. Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction Over Time

Table S4. Multivariate Predictors of Pacemaker Implantation at 30 Days in Lotus Patients

Table S5. Multivariate Predictors of Pacemaker Implantation at 30 Days in CoreValve Patients

Table S6. Outcomes Between 31 Days and 1 Year Stratified by Pacemaker Dependency at 30 Days

Table S7. Multivariate Predictors of Pacemaker Dependency at 30 Days

Table S8. Multivariate Predictors of Pacemaker Dependency at 1 y

Figure S1. Pre‐specified pacemaker dependency algorithm.

Figure S2. Pacemaker dependency at 30 days and 1 year.

Figure S3. Quality of life outcomes in patients with a new pacemaker.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kristine Roy, PhD (Boston Scientific Corporation) for assistance in manuscript preparation and Hong Wang, MS (Boston Scientific Corporation) for assistance with statistical analysis.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e012594 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012594.)

References

- 1. Auffret V, Puri R, Urena M, Chamandi C, Rodriguez‐Gabella T, Philippon F, Rodés‐Cabau J. Conduction disturbances after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: current status and future perspectives. Circulation. 2017;136:1049–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Siontis GC, Juni P, Pilgrim T, Stortecky S, Bullesfeld L, Meier B, Wenaweser P, Windecker S. Predictors of permanent pacemaker implantation in patients with severe aortic stenosis undergoing TAVR: a meta‐analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:129–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Franzone A, Windecker S. The conundrum of permanent pacemaker implantation after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:e005514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Feldman TE, Reardon MJ, Rajagopal V, Makkar RR, Bajwa TK, Kleiman NS, Linke A, Kereiakes DJ, Waksman R, Thourani VH, Stoler RC, Mishkel GJ, Rizik DG, Iyer VS, Gleason TG, Tchétché D, Rovin JD, Buchbinder M, Meredith IT, Götberg M, Bjursten H, Meduri C, Salinger MH, Allocco DJ, Dawkins KD. Effect of mechanically expanded vs self‐expanding transcatheter aortic valve replacement on mortality and major adverse clinical events in high‐risk patients with aortic stenosis: the REPRISE III randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:27–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kappetein AP, Head SJ, Genereux P, Piazza N, van Mieghem NM, Blackstone EH, Brott TG, Cohen DJ, Cutlip DE, van Es GA, Hahn RT, Kirtane AJ, Krucoff MW, Kodali S, Mack MJ, Mehran R, Rodes‐Cabau J, Vranckx P, Webb JG, Windecker S, Serruys PW, Leon MB. Updated standardized endpoint definitions for transcatheter aortic valve implantation: the valve academic research consortium‐2 consensus document. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1438–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dumonteil N, Meredith IT, Blackman DJ, Tchétché D, Hildick‐Smith D, Spence MS, Walters DL, Harnek J, Worthley SG, Rioufol G, Lefèvre T, Modine T, Van Mieghem N, Houle VM, Allocco DJ, Dawkins KD. Insights into the need for permanent pacemaker following implantation of the repositionable LOTUS™ valve for the transcatheter aortic valve replacement in 250 patients: results from the REPRISE II trial with extended cohort. EuroIntervention. 2017;13:796–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alasti M, Rashid H, Rangasamy K, Kotschet E, Adam D, Alison J, Gooley R, Zaman S. Long‐term pacemaker dependency and impact of pacing on mortality following transcatheter aortic valve replacement with the LOTUS valve. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv.2018;92:777–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van Gils L, Wöhrle J, Hildick‐Smith D, Bleiziffer S, Blackman DJ, Abdel‐Wahab M, Gerckens U, Brecker S, Bapat V, Modine T, Soliman OI, Nersesov A, Allocco D, Falk V, Van Mieghem NM. Importance of contrast aortography with lotus transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a post hoc analysis from the RESPOND post‐market study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:119–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Binder RK, Webb JG, Toggweiler S, Freeman M, Barbanti M, Willson AB, Alhassan D, Hague CJ, Wood DA, Leipsic J. Impact of post‐implant SAPIEN XT geometry and position on conduction disturbances, hemodynamic performance, and paravalvular regurgitation. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:462–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Auffret V, Webb JG, Eltchaninoff H, Muñoz‐García AJ, Himbert D, Tamburino C, Nombela‐Franco L, Nietlispach F, Morís C, Ruel M, Dager AE, Serra V, Cheema AN, Amat‐Santos IJ, de Brito FS, Lemos PA, Abizaid A, Sarmento‐Leite R, Dumont E, Barbanti M, Durand E, Alonso García del JH, Vahanian A, Bouleti C, Immè S, Maisano F, del Valle R, Benitez LM, García del Blanco B, Puri R, Philippon F, Urena M, Rodés‐Cabau J. Clinical impact of baseline right bundle branch block in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:1564–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Terré JA, George I, Smith CR. Pros and cons of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI). Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;6:444–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Young MN, Inglessis I. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement: outcomes, indications, complications, and innovations. Curr Treat Options Cardio Med. 2017;19:81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bob‐Manuel T, Nanda A, Latham S, Pour‐Ghaz I, Skelton WP, Khouzam RN. Permanent pacemaker insertion in patients with conduction abnormalities post transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a review and proposed guidelines. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fadahunsi OO, Olowoyeye A, Ukaigwe A, Li Z, Vora AN, Vemulapalli S, Elgin E, Donato A. Incidence, predictors, and outcomes of permanent pacemaker implantation following transcatheter aortic valve replacement: analysis from the U.S. Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology TVT Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:2189–2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thyregod HGH . Abstract Presented: Five‐Year Outcomes From the All‐Comers Nordic Aortic Valve Intervention Randomized Clinical Trial in Patients with Severe Aortic Valve Stenosis. 2018. Available at: https://www.acc.org/~/media/Clinical/PDF-Files/Approved-PDFs/2018/03/05/ACC18_Slides/March10_Sat/1215pmET-NOTION-acc-2018.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2019.

- 16. Chamandi C, Barbanti M, Munoz‐Garcia A, Latib A, Nombela‐Franco L, Gutiérrez‐Ibanez E, Veiga‐Fernandez G, Cheema AN, Cruz‐Gonzalez I, Serra V, Tamburino C, Mangieri A, Colombo A, Jiménez‐Quevedo P, Elizaga J, Laughlin G, Lee D‐H, Garcia del Blanco B, Rodriguez‐Gabella T, Marsal J‐R, Côté M, Philippon F, Rodés‐Cabau J. Long‐term outcomes in patients with new permanent pacemaker implantation following transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:301–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Naveh S, Perlman GY, Elitsur Y, Planer D, Gilon D, Leibowitz D, Lotan C, Danenberg H, Alcalai R. Electrocardiographic predictors of long‐term cardiac pacing dependency following transcatheter aortic valve implantation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2017;28:216–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Renilla A, Rubín JM, Rozado J, Moris C. Long‐term evolution of pacemaker dependency after percutaneous aortic valve implantation with the corevalve prosthesis. Int J Cardiol. 2015;201:61–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van der Boon RMA, Van Mieghem NM, Theuns DA, Nuis R‐J, Nauta ST, Serruys PW, Jordaens L, van Domburg RT, de Jaegere PPT. Pacemaker dependency after transcatheter aortic valve implantation with the self‐expanding Medtronic CoreValve System. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:1269–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pereira E, Ferreira N, Caeiro D, Primo J, Adao L, Oliveira M, Goncalves H, Ribeiro J, Santos E, Leite D, Bettencourt N, Braga P, Simoes L, Vouga L, Gama V. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation and requirements of pacing over time. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2013;36:559–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nazif TM, Dizon JM, Hahn RT, Xu K, Babaliaros V, Douglas PS, El‐Chami MF, Herrmann HC, Mack M, Makkar RR, Miller DC, Pichard A, Tuzcu EM, Szeto WY, Webb JG, Moses JW, Smith CR, Williams MR, Leon MB, Kodali SK. Predictors and clinical outcomes of permanent pacemaker implantation after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: the PARTNER (Placement of AoRtic TraNscathetER Valves) Trial and Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:60–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Urena M, Webb JG, Cheema A, Serra V, Toggweiler S, Barbanti M, Cheung A, Ye J, Dumont E, Delarochelliere R, Doyle D, Al Lawati HA, Peterson M, Chisholm R, Igual A, Ribeiro HB, Nombela‐Franco L, Philippon F, Garcia del Blanco B, Rodes‐Cabau J. Impact of new‐onset persistent left bundle branch block on late clinical outcomes in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation with a balloon‐expandable valve. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:128–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ramazzina C, Knecht S, Jeger R, Kaiser C, Schaer B, Osswald S, Sticherling C, KÜHne M. Pacemaker implantation and need for ventricular pacing during follow‐up after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2014;37:1592–1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weber M, Sinning J‐M, Hammerstingl C, Werner N, Grube E, Nickenig G. Permanent pacemaker implantation after TAVR—predictors and impact on outcomes. Interv Cardiol. 2015;10:98–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fraccaro C, Napodano M, Tarantini G. Conduction disorders in the setting of transcatheter aortic valve implantation a clinical perspective. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;81:1217–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rodés‐Cabau J, Urena M, Nombela‐Franco L, Amat‐Santos I, Kleiman N, Munoz‐Garcia A, Atienza F, Serra V, Deyell MW, Veiga‐Fernandez G, Masson J‐B, Canadas‐Godoy V, Himbert D, Castrodeza J, Elizaga J, Francisco Pascual J, Webb JG, de la Torre JM, Asmarats L, Pelletier‐Beaumont E, Philippon F. Arrhythmic burden as determined by ambulatory continuous cardiac monitoring in patients with new‐onset persistent left bundle branch block following transcatheter aortic valve replacement: the MARE study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:1495–1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vijayaraman P, Dandamudi G. Anatomical approach to permanent His bundle pacing: optimizing His bundle capture. J Electrocardiol. 2016;49:649–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reddy VY, Exner DV, Cantillon DJ, Doshi R, Bunch TJ, Tomassoni GF, Friedman PA, Estes NAM, Ip J, Niazi I, Plunkitt K, Banker R, Porterfield J, Ip JE, Dukkipati SR; LEADLESS II Study Investigators . Percutaneous implantation of an entirely intracardiac leadless pacemaker. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1125–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Supplemental Methods.

Table S1. Additional Baseline Characteristics by Pacemaker Status at 30 Days

Table S2. Outcomes Between 31 Days and 1 Year in Patients Who Had a Prior Pacemaker, no Pacemaker or New Pacemaker at 30 Days

Table S3. Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction Over Time

Table S4. Multivariate Predictors of Pacemaker Implantation at 30 Days in Lotus Patients

Table S5. Multivariate Predictors of Pacemaker Implantation at 30 Days in CoreValve Patients

Table S6. Outcomes Between 31 Days and 1 Year Stratified by Pacemaker Dependency at 30 Days

Table S7. Multivariate Predictors of Pacemaker Dependency at 30 Days

Table S8. Multivariate Predictors of Pacemaker Dependency at 1 y

Figure S1. Pre‐specified pacemaker dependency algorithm.

Figure S2. Pacemaker dependency at 30 days and 1 year.

Figure S3. Quality of life outcomes in patients with a new pacemaker.