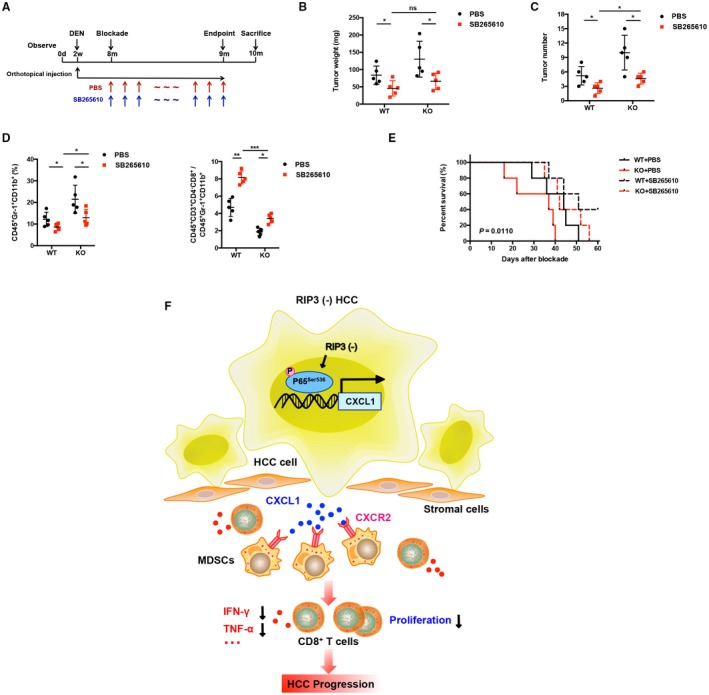

Figure 8.

Blockade of CXCR2 reverses MDSC chemotaxis mediated by RIP3 deficiency to the tumor. (A) Flowchart of DEN (25 mg/kg)–induced HCC models in RIP3 KO mice and littermates. SB265610 (2 mg/kg body weight) or PBS was injected intraperitoneally every day since the eighth month after birth. (B) Tumor weight and (C) tumor number were monitored (left, weight; right, number; n = 5). *P < 0.05. (D) Flow‐cytometric analyses of DEN‐induced HCC of RIP3 KO mice or littermates treated by SB265610 or PBS. Percentage of positive cells relative to total cells is plotted. MDSCs (left) and CD8+ T cells/MDSCs (right) (n = 5). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (E) The probability of overall survival was significantly different in DEN‐induced HCC of RIP3 KO mice or littermates treated by SB265610 or PBS. (F) Schematic representation of RIP3 signaling in HCC immune evasion. Hepatic RIP3 deficiency promotes HCC immune escape by up‐regulation of CXCL1 and recruitment of MDSCs through CXCR2, the exclusive cognate receptor of CXCL1. RIP3 inhibits CXCL1 expression by disrupting phosphorylation of P65Ser536 and inhibiting p‐P65Ser536 nuclear translocation, as well as its direct co‐occupancy of CXCL1 promoter. Abbreviation: ns, nonsignificant.