Abstract

Disulfide bond-disrupting agents (DDAs) are a new chemical class of agents recently shown to have activity against breast tumors in animal models. Blockade of tumor growth is associated with downregulation of EGFR, HER2, and HER3 and reduced Akt phosphorylation, as well as the induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress. However, it is not known how DDAs trigger cancer cell death without affecting nontransformed cells. As demonstrated here, DDAs are the first compounds identified that upregulate the TRAIL receptor DR5 through transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms to activate the extrinsic cell death pathway. At the protein level, DDAs alter DR5 disulfide bonding to increase steady-state DR5 levels and oligomerization, leading to downstream caspase 8 and 3 activation. DDAs and TRAIL synergize to kill cancer cells and are cytotoxic to HER2+ cancer cells with acquired resistance to the EGFR/HER2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor Lapatinib. Investigation of the mechanisms responsible for DDA selectivity for cancer cells reveals that DDA-induced upregulation of DR5 is enhanced in the context of EGFR overexpression. DDA-induced cytotoxicity is strongly amplified by MYC overexpression. This is consistent with the known potentiation of TRAIL-mediated cell death by MYC. Together, the results demonstrate selective DDA lethality against oncogene-transformed cells, DDA-mediated DR5 upregulation, and protein stabilization, and that DDAs have activity against drug-resistant cancer cells. Our results indicate that DDAs are unique in causing DR5 accumulation and oligomerization and inducing downstream caspase activation and cancer cell death through mechanisms involving altered DR5 disulfide bonding. DDAs thus represent a new therapeutic approach to cancer therapy.

Subject terms: Breast cancer, Oncogenes

Introduction

Drugs exist for tumors overexpressing human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) or epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinases. However, drug resistance is a common problem. Tumors that lack estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER2 are termed “Triple-Negative” Breast Cancers (TNBCs). TNBCs resist most targeted therapies. EGFR is overexpressed in a substantial fraction of TNBCs and is a potential therapeutic target1, but EGFR-targeted therapies have not exhibited sufficient activity against EGFR+ TNBCs. EGFR and HER2-specific drugs act through the mechanism of oncogene addiction. Cancers often escape from oncogene addiction. Synthetic lethality relies on drug actions that manifest selectively in the context of tumor-associated genetic alterations. Given the current limitations of EGFR and HER2-targeted drugs in treating breast cancer, new agents that act through a synthetic lethal mechanism could benefit patients with EGFR+ TNBCs and drug- resistant HER2+ tumors.

Previous reports2–4 describe a novel class of anticancer agents termed disulfide bond-disrupting agents (DDAs). DDAs kill cancer cells that overexpress EGFR or HER24, and DDAs decrease expression of EGFR, HER2, and HER3 and reduce phosphorylation of the pro-survival kinase Akt. DDA-mediated cancer cell death is also associated with activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR)2. The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress that triggers the UPR can activate multiple cell death pathways (reviewed in ref. 5). However, the specific cell death mechanisms engaged by the DDAs remain unexplored.

Irremediable ER stress can drive apoptosis by upregulating the death receptor 5 (DR5) protein through transcriptional mechanisms6–9. Activation of DR5 by its ligand, TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), selectively kills cancer cells without effects on nontransformed cells, and shows manageable side effects in clinical trials10–12. However, TRAIL and other DR5 agonists have not met expectations in clinical trials, in part because cancer cells can easily become TRAIL resistant by downregulating DR513–15. A strategy for increasing DR5 levels and activating downstream DR5 apoptotic signaling could bypass the resistance to TRAIL and DR5 agonist antibodies observed in the clinic.

Results

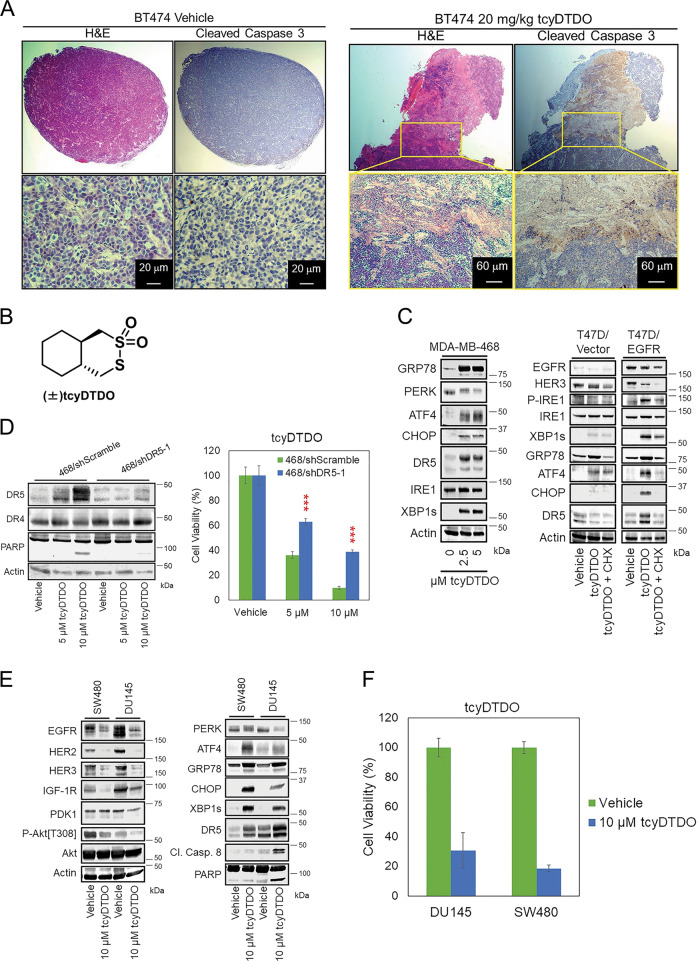

DDAs activate the extrinsic apoptosis pathway to kill EGFR+ and HER2+ cancers

Breast cancer cells that overexpress EGFR or HER2 are sensitive to DDAs2,4,16. Past work employed MDA-MB-468 TNBC cells and BT474 luminal B cells as models of EGFR and HER2-overexpressing breast cancer, respectively. Consistent with these previous studies, DDAs show extensive anticancer effects in vivo. Mice bearing orthotopic xenograft BT474 tumors were treated with vehicle (DMSO) or different doses of our most highly potent DDA tcyDTDO16 for 5 days. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) histochemical staining revealed that the tumors were substantially necrotic after tcyDTDO treatment (Fig. 1a, left panels). Cleaved caspase 3 staining indicated tumor cell death due to apoptosis (Fig. 1a, right panels). To investigate which pathway mediates DDA-induced tumor cell death, we screened multiple cell death axes. Immunoblot analyses showed that tcyDTDO (Fig. 1b) significantly increased the levels of DR5 (Fig. 1c, left panel), suggesting that DDAs activate extrinsic apoptosis in cancer cells. T47D cells model low EGFR/HER2 luminal A cancers2,4,16. These studies showed that T47D cells overexpressing EGFR or HER2 are highly sensitive to DDAs. Therefore, we examined whether DR5 expression increases in EGFR-overexpressing T47D cells treated with DDAs. TcyDTDO activated ER stress and upregulated DR5 in T47D/EGFR cancer cells, but not T47D/vector cells (Fig. 1c, right panel). The combination of tcyDTDO and Cycloheximide (CHX), a protein synthesis inhibitor, reversed DDA-induced upregulation of ER stress and DR5, indicating that DDA-triggered ER stress is responsible for increasing DR5 levels. To confirm that DR5 is critical for regulating the sensitivity of cancer cells to DDAs, we generated DR5 knockdown MDA-MB-468 lines (Fig. 1d). Knockdown of DR5 decreased PARP cleavage and partially reduced sensitivity of cancer cells to tcyDTDO treatments in MTT assays (Fig. 1d).

Fig. 1. DDAs activate the extrinsic apoptosis pathway to kill EGFR+ and HER2+ cancers.

a Tumor-bearing mice were randomly separated into two groups of three mice each and treated once daily for 5 days with either vehicle (DMSO) or 20 mg/kg tcyDTDO. Mice were killed on day 5 (3 h after treatments) and tumor samples were collected for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and cleaved caspase 3 staining. b Structure of DDA tcyDTDO. c MDA-MB-468 and the indicated T47D stable cell lines treated for 24 h have been indicated and cell extracts were analyzed by immunoblot. d Left panel. Immunoblot analyses were performed on the indicated MDA-MB-468 lentivirally transduced shRNA knockdown cell lines with 5 or 10 µM tcyDTDO treatments. Right panel. MTT assays were performed on the same cell lines treated with the indicated concentrations of tcyDTDO for 72 h. e SW480 and DU145 cell lines were treated as indicated for 24 h and analyzed by immunoblot. f MTT assays were performed on SW480 and DU145 cells with indicated treatments for 72 h. The results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of five replicate determinations. Significance was determined using Student’s t test with ***P ≤ 0.001.

We previously demonstrated that DDA treatment kills cancer cells that overexpress EGFR and/or HER216. The human tumor lines DU145 (prostate) and SW480 (colon) are DDA-sensitive non-breast cancer cell lines. TcyDTDO downregulated the expression levels of EGFR/HER2/HER3, induced Akt dephosphorylation, and caused ER stress in these cells (Fig. 1e). Importantly, tcyDTDO also triggered the extrinsic apoptosis pathway as measured by the upregulation of DR5, CC8, and PARP cleavage, and significant reduction of cell viability (Fig. 1f). These data suggest that DDAs activate the extrinsic apoptosis pathway to kill EGFR+ and HER2+ cancers.

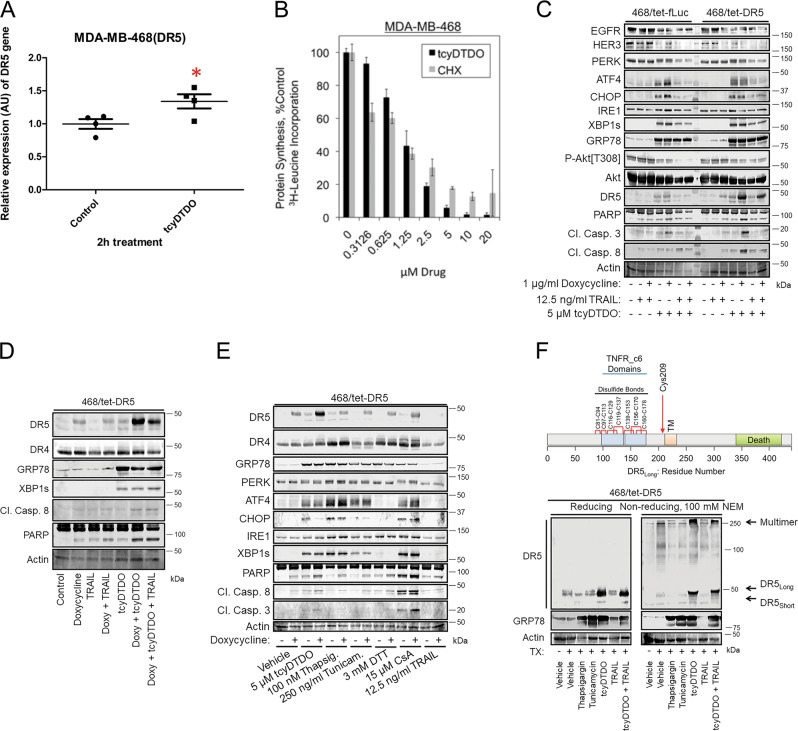

DDAs upregulate DR5 through both transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms, by altering DR5 disulfide-bonding pattern and promoting its oligomerization

ER stress increases the transcription of the gene encoding DR5 through activation of transcription factors ATF4 and CHOP17–19. Therefore, we examined whether tcyDTDO activates a previously described13 DR5 transcriptional reporter construct. TcyDTDO (5 µM) stimulated a several-fold increase in the activity of the DR5 reporter (Fig. S1A), suggesting a transcriptional mechanism. To validate this finding in cancer cells, time-course treatments (2–16 h) of MDA-MB-468 cells with 5 µM tcyDTDO were performed, and the mRNA level of DR5 was measured by RT-PCR and quantitative PCR. As shown in Figs. 2a and S1B, the increase in DR5 mRNA level was only detected at 2 h after tcyDTDO treatment, and only caused a 1.5-fold change. Since CHOP regulates DR5 expression, we constructed MDA-MB-468 and SKBR3 cell lines encoding either tetracycline-inducible control vector (468/tet-Puro) or CHOP (468/tet-CHOP), and knocked down CHOP in BT474 cells to study the effects of CHOP on DR5 levels in response to DDAs. CHOP overexpression failed to increase DR5 levels with or without DDA treatment (Fig. S1C, D), and CHOP knockdown only partly blocked DDA-mediated DR5 upregulation (Fig. S1E). These data suggest that tcyDTDO weakly increases the transcription of DR5. ER stress also reduces protein synthesis through PERK-dependent phosphorylation of eIF2α, so we examined the effect of tcyDTDO on protein synthesis. TcyDTDO suppressed protein synthesis in a concentration-dependent manner similarly to the protein synthesis inhibitor Cycloheximide (CHX) (Fig. 2b). Therefore, we hypothesized that DDAs regulate DR5 levels through post-transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms. We constructed stable MDA-MB-468 cell lines to inducibly express the long alternative splice variant of DR5 (468/tet-DR5), or firefly luciferase (468/tet-fLuc) as a control, to study the effects of DDAs on DR5 steady-state protein levels. In the 468/tet-DR5 cells, doxycycline + tcyDTDO robustly upregulated DR5 associated with strong induction of caspase 8 and 3 cleavage (Fig. 2c). In contrast, in the 468/tet-fLuc cells, doxycycline + tcyDTDO induced a weaker upregulation of DR5 and caspase 3 and 8 cleavage. Examining combinations of doxycycline, tcyDTDO, and TRAIL on 468/tet-DR5 cells demonstrated that the highest levels of the long form of DR5 were achieved by combining doxycycline and tcyDTDO (Fig. 2d), suggesting that tcyDTDO may stabilize DR5 at the protein level. These treatments did not alter the levels of DR4 (Fig. 2e). Comparison of tcyDTDO with other activators of the UPR demonstrated that at similar levels of ER stress induction, tcyDTDO produced the highest level of steady-state DR5 (Fig. 2e). Interestingly, levels of DR4 were increased by ER stressors that disrupt Ca2+ homeostasis (thapsigargin), reduce disulfide bonds (dithiothreitol (DTT)), and inhibit proline cis-/trans-isomerization (cyclosporine A (CsA)), while DR4 levels were not significantly altered by tcyDTDO. The DR5 extracellular domain contains seven disulfide bonds20,21 and DR5Long contains an additional unpaired Cys, Cys 209, that is not present in DR5Short (Fig. 2f, upper panel). Based on our previous proposal that DDA actions are mediated through effects on disulfide bond formation4, we examined if tcyDTDO alters the disulfide-bonding pattern of DR5. Immunoblot analysis of 468/tet-DR5 samples, which were prepared under reducing or nonreducing conditions in the presence of 100 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) to prevent disulfide exchange after lysis, was used to compare the effects of multiple ER stress inducers on DR5 (Fig. 2f, lower panel). Analysis under reducing conditions revealed that thapsigargin, tunicamycin, and tcyDTDO induced comparable ER stress as measured by GRP78, but tcyDTDO had the strongest effect in upregulating DR5. Analysis under nonreducing conditions indicated that only tcyDTDO treatment shifted migration of DR5Long monomer and increased accumulation of the disulfide-bonded multimeric form of DR5 at the top of the gel. MG132 and b-AP15 induce DR5 accumulation by inhibiting the proteasome and proteasome-associated deubiquitinases, respectively13,22–24. TcyDTDO, but not thapsigargin, tunicamycin, b-AP15, MG132, or TRAIL, reduced the electrophoretic ability of both DR5Long and DR5Short under nonreducing conditions in various cell lines (Fig. S2A–C). These results suggest that tcyDTDO altered the disulfide-bonding pattern of DR5long, and increased the formation of DR5 multimers by promoting the formation of intermolecular disulfide bonds.

Fig. 2. DDAs upregulate DR5 through transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms.

a MDA-MB-468 cells were treated with DMSO or 5 µM tcyDTDO for 2 h. Total RNA was isolated from each sample and converted to cDNA using reverse transcriptase. The mRNA levels of DR5 were measured using real-time qPCR, and relative mRNA expression was calculated. Fold change was calculated by normalizing all values to the untreated group. T test showed p = 0.0395. b Protein synthesis was assessed by 3H-leucine incorporation in MDA-MB-468 cells treated with the indicated concentrations of tcyDTDO or cycloheximide (CHX). c Immunoblot analysis of MDA-MB-468 cells engineered to express DR5 in a tetracycline-inducible manner (468/tet-DR5) and the corresponding control cell line (468/tet-fLuc) after the indicated 24-h treatments. d Immunoblot analysis of 468/tet-DR5 cells treated separately or with combinations of 1 µg/ml doxycycline, 12.5 ng/ml TRAIL, and 5 µM tcyDTDO for 24 h. e Immunoblot analysis of 468/tet-DR5 cells treated with the indicated agents for 24 h. f Upper panel. Diagram based on DR5 crystal structures showing the presence of seven intramolecular disulfide bonds and an unpaired cysteine residue in the extracellular domain of DR5. Lower panel. Immunoblot analysis of DR5 from 468/tet-DR5 cells treated for 24 h as indicated under nonreducing and reducing conditions. Cell extraction in the presence of N-ethylmaleimide NEM (100 mM) was used to limit thiol–disulfide exchange under nonreducing conditions.

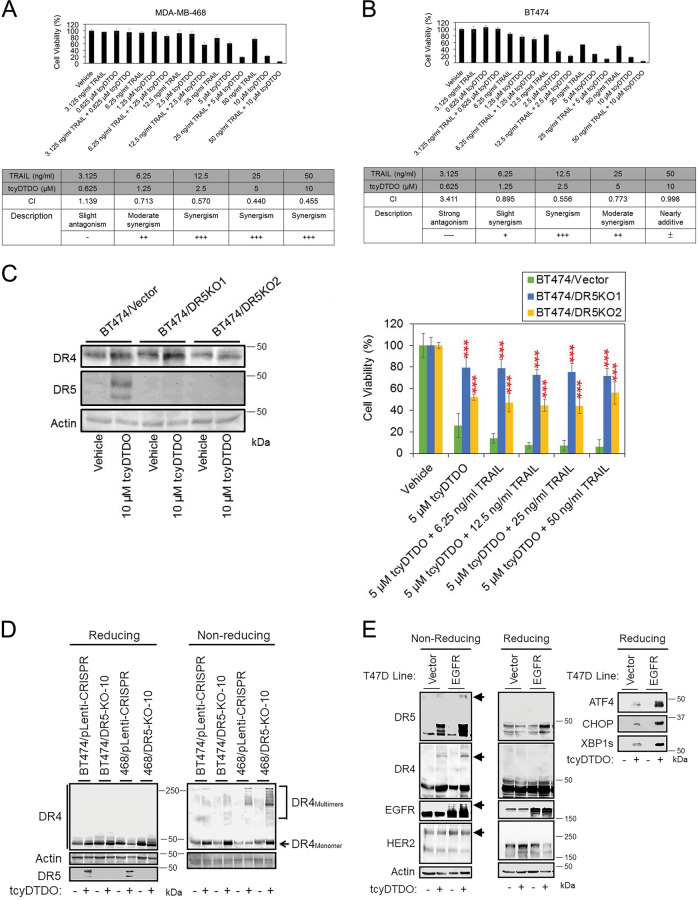

DDA upregulation of DR5 correlates with sensitization to TRAIL

Since DDAs stabilize DR5 protein level through a post-transcriptional mechanism, we investigated whether DDA sensitizes cancer cells to TRAIL. Cell viability studies were performed in MDA-MB-468 (Fig. 3a) and BT474 (Fig. 3b) cells and synergy was analyzed using the Chou–Talalay method25,26. The results showed that the combination of tcyDTDO and TRAIL induces strong synergy in killing both cell lines. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing was used to generate DR5-knockout BT474 clones that were compared with control cells (Fig. 3c, left panel). Cell viability assays confirmed that ablation of DR5 expression reduced the sensitivity of cells to tcyDTDO treatment, or combined tcyDTDO/TRAIL treatment (Fig. 3c, right panel). Loss of DR5 expression did not fully rescue cell death from tcyDTDO + TRAIL treatments, so we hypothesized that DR4 might be activated by tcyDTDO after DR5 was knocked out. Vector control cells and DR5-knockout clones from different cell lines were treated in the presence or absence of tcyDTDO, and cell lysates were prepared in reducing or nonreducing conditions (Fig. 3d). TcyDTDO did not upregulate the total protein levels of DR4, but strongly induced DR4 oligomerization in DR5-knockout cells (Fig. 3d). TcyDTDO more strongly stimulated DR5 oligomerization in T47D/EGFR than in T47D/vector cells, suggesting that EGFR overexpression potentiates the effects of tcyDTDO on DR5 (Fig. 3e). Together, the results in Fig. 3 demonstrate that tcyDTDO sensitizes cancer cells to TRAIL through DR5 upregulation and oligomerization.

Fig. 3. DDA upregulation of DR5 correlates with sensitization to TRAIL.

a, b MTT cell viability assays performed on MDA-MB-468 and BT474 cells, respectively, after 72 h of the indicated treatments (upper panel) and analyzed using the Chou–Talalay method to calculate combination indices (CIs) (lower panel). [CIs: =1, >1, and <1 represent additivity, antagonism, and synergy, respectively.] Graphs represent the average of quadruplicate determinations ± standard deviation. c Left panel. Immunoblot analysis of BT474 control and DR5-knockout (DR5-KO) clones after a 24-h treatment with vehicle or 10 µM tcyDTDO. Right panel. MTT cell survival assays performed on BT474 control and DR5 -knockout clones after 72 h of the indicated treatments. d Immunoblot analysis showing comparison of DR4 oligomerization in MDA-MB-468 and BT474 vector control or DR5-knockout clones. e The indicated T47D cell lines were treated in the presence or absence of 5 µM tcyDTDO for 24 h. Samples were collected under reducing and nonreducing conditions for immunoblot analyses.

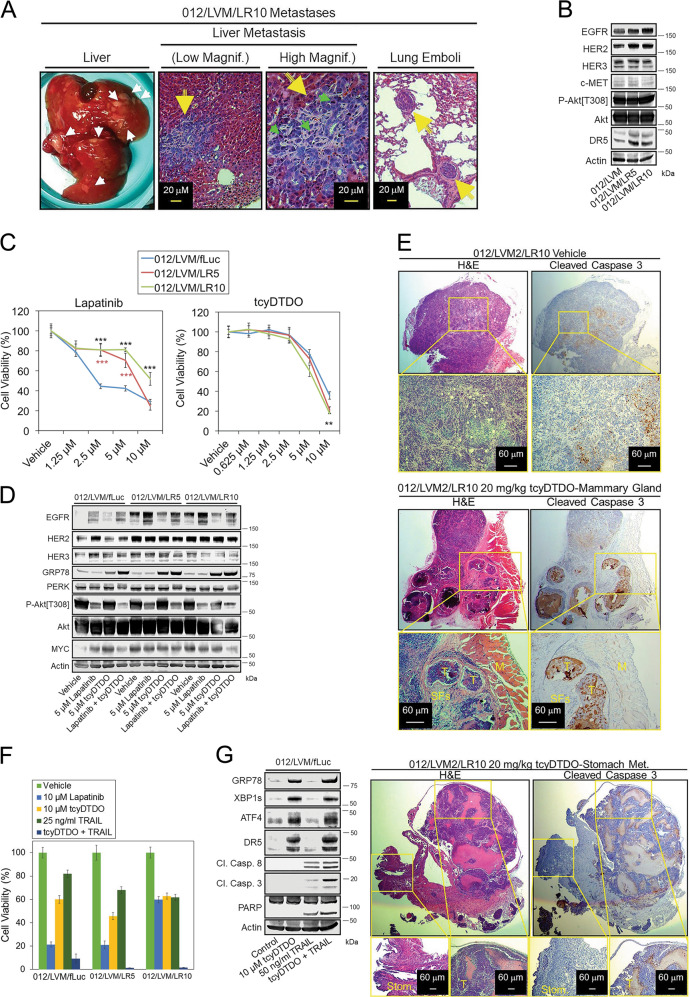

DDAs kill Lapatinib-resistant breast cancer cells

We previously isolated a cell line termed HCI-01216 obtained from a patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model of the same name. The HCI-012 xenograft originated from a patient with HER2+ breast cancer that metastasized and resisted treatment with cytotoxic and targeted (Lapatinib/Trastuzumab) therapy27. We selected sublines of the HCI-012 cells to model drug-resistant and metastatic breast cancers in two steps. We first isolated HCI-012 sublines capable of colonizing mouse lungs and liver after injection into either the tail vein or mammary gland (Fig. 4a). Second, continuous growth of the HCI-012 cells from liver metastases (012/LVM) in the presence of either 5 or 10 µM Lapatinib produced the Lapatinib-resistant sublines 012/LVM/LR5 and 012/LVM/LR10, respectively. Immunoblot analysis showed that the Lapatinib-resistant lines expressed higher levels of EGFR, HER2, and DR5 (Fig. 4b). Lapatinib cytotoxicity was reduced in the Lapatinib-resistant lines (Fig. 4c), but the sensitivity of all three cell lines to tcyDTDO was similar. Treatment of the control cell lines with Lapatinib increased expression of EGFR and HER2, and this effect was more dramatic in the Lapatinib-resistant lines (Fig. 4d). This suggests that the Lapatinib resistance may be due to Lapatinib upregulating EGFR and HER2 in addition to higher basal EGFR and HER2 levels in these cells. TcyDTDO partially decreased EGFR expression and Akt phosphorylation in control and Lapatinib-resistant cells. To study anticancer activities of tcyDTDO against Lapatinib-resistant tumors in vivo, eight mice were injected with HCI-012/LVM/LR10 cells in their mammary fat pads. After volumes of the primary tumors reached 100 mm3, mice were randomly assigned into two groups and treated once daily with vehicle or 20 mg/kg of tcyDTDO for 5 consecutive days by intraperitoneal injection. H&E staining of tumor tissue showed that both the primary and metastatic tumors from tcyDTDO-treated mice were necrotic, and large numbers of dying cells were observed surrounding the necrotic areas (Fig. 4e). Cleaved caspase 3 staining of serial sections confirmed that the apoptotic pathway was activated, especially surrounding the tumor necrotic areas (Fig. 4e). Importantly, tcyDTDO only induced apoptosis of cancer cells, while the normal muscle and stomach tissues remained intact, indicating selectivity of tcyDTDO toward cancer cells (Fig. 4e).

Fig. 4. DDAs kill Lapatinib-resistant cancer cells.

a Micrographs of liver metastases and lung tumor emboli generated in mice by a HCI-012 cell line selected for liver metastasis (LVM) and growth in the presence of 10 µM Lapatinib (LR10). b Immunoblot analysis of parental liver metastatic HCI-012 cells (012/LVM), or sublines selected for growth in 5 (LR5) or 10 µM (LR10) Lapatinib. c MTT cell viability assays on the indicated cell lines after treatment for 72 h with increasing concentrations of Lapatinib (left panel) or tcyDTDO (right panel). d Immunoblot analysis of the indicated cell lines treated for 24 h with the specified concentrations of Lapatinib, tcyDTDO, or Lapatinib + tcyDTDO. e Tumor-bearing mice were randomly separated into two groups of four mice each and treated for 5 days with either vehicle (DMSO) or 20 mg/kg of tcyDTDO. Mice were killed at day 5 (3 h after treatments) and tumor samples and metastatic lesions were collected for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and cleaved caspase 3 staining. Abbreviations used include M, muscle tissue; T, tumor tissue; SFs, stromal fibroblasts. f MTT cell viability assays performed after a 72-h treatment with 10 µM Lapatinib, 10 µM tcyDTDO, 25 ng/ml TRAIL, or tcyDTDO + TRAIL. g Immunoblot analysis of 012/LVM/fLuc cells treated for 24 h as specified. 012/LVM/fLuc cells were labeled using a lentiviral firefly luciferase vector as described in the “Materials and methods” section.

Combining tcyDTDO and TRAIL may be an effective strategy against Lapatinib-resistant 012/LVM lines, as the viability of these cells was somewhat decreased by treatment with either tcyDTDO or TRAIL, but tcyDTDO + TRAIL dramatically reduced the viability of all three lines (Fig. 4f). TcyDTDO and TRAIL-induced cell death was apparent as demonstrated by reduced cell numbers and apoptotic cell morphology in photomicrographs (Fig. S2D). Consistent with these observations, co-treatment with tcyDTDO and TRAIL resulted in maximal caspase 8, caspase 3, and PARP cleavage, indicative of the induction of apoptosis through the extrinsic death pathway (Fig. 4g).

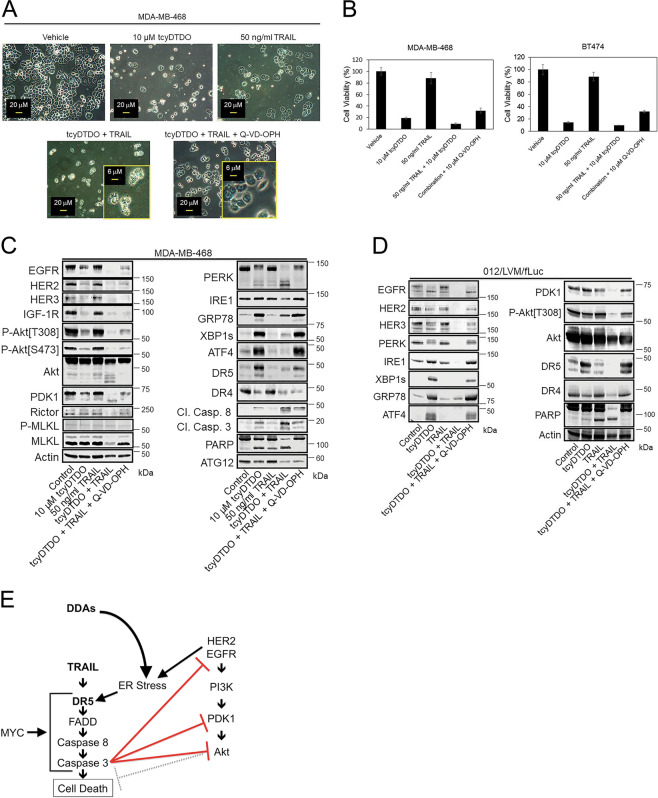

While our data show that DDAs trigger extrinsic apoptosis, as indicated by the activation of DR5, caspases 8 and 3, and PARP cleavage, we do not always observe a direct correlation between increased activity of caspases 8 and 3 and DR4 or DR5 levels. There are several possible explanations for these discrepancies. Based on previous work28, DDA-mediated ER stress might activate caspase 12, which in turn could activate caspase 3. It is also possible that DDA-mediated ER stress increases the expression of inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) such as cIAP1 or cIAP229, which could impact the levels of activated caspases 8 and 3. Further, DR5 is required for maximal DDA induction of apoptosis (Figs. 1d and 3c), but death receptors can activate caspases 8 and 1030, so the relative DDA activation of caspases 8 and 10 could explain the absence of a perfect correlation between caspases 8 and 3 activation. However, a central role for caspase activation in mediating the anticancer actions of DDAs is indicated by the observations that (1) the caspase inhibitor Q-VD-OPH reverses many of the biochemical and biological responses to DDAs, with the exception of the DDA-mediated ER stress response (Fig. 5c), and (2) mouse tumor studies demonstrate strong DDA induction of caspase 3 cleavage by DDAs in cancer cells in vivo, but not in the surrounding normal tissues (Fig. 4e).

Fig. 5. Caspases mediate DDA/TRAIL-induced downregulation of EGFR and PDK1.

a Micrographs of MDA-MB-468 cells treated as indicated for 24 h showing cytotoxicity of tcyDTDO and TRAIL and prevention of cell death by the caspase inhibitor Q-VD-OPH (10 µM). b MTT assays were performed on MDA-MB-468 and BT474 cells with indicated treatments for 72 h. c Immunoblot analysis of MDA-MB-468 cells treated as in a. d Immunoblot analysis of 012/LVM/fLuc cells treated for 24 h as indicated. e Model for how DDAs and TRAIL reduce the levels of PERK, EGFR, PDK1, and Akt by inducing their caspase-dependent degradation.

Caspases mediate DDA/TRAIL-induced downregulation of EGFR and PDK1

As with the HCI-012 cell lines, tcyDTDO and TRAIL co-treatment killed MDA-MB-468 and BT474 cells more effectively than either agent alone (Fig. 5a and S2E). The caspase inhibitor Q-VD-OPH partially rescued the cells from tcyDTDO + TRAIL-mediated cell death (Fig. 5a, b). Rescue was associated with reversal of the rounded and apoptotic morphology of cells treated with tcyDTDO to the attached, spread morphology observed with the vehicle-treated cells. Immunoblot analysis indicated that tcyDTDO increased expression of DR5, but not DR4, and tcyDTDO + TRAIL strongly decreased EGFR, HER2, HER3, and IGF-1R expression and Akt phosphorylation (Fig. 5c). TcyDTDO + TRAIL induced the degradation of Akt, PDK1, and PERK based on the loss of the parent bands and formation of more rapidly migrating species. These effects were reversed by caspase inhibition. EGFR31 and Akt32 are caspase substrates. We are not aware of reports showing that PDK1 or PERK are degraded via a caspase-dependent mechanism. TRAIL + tcyDTDO produced near-complete PARP cleavage, which was reversed by Q-VD-OPH. In some systems, ER stress upregulates ATG12 and initiates autophagy33, or induces necroptosis34. In MDA-MB-468 cells, tcyDTDO + TRAIL did not increase expression of the autophagy marker ATG12 or the necroptosis marker phospho-MLKL, suggesting that cell death is predominantly through caspase-dependent apoptosis (Fig. 5c). Similarly, in 012/LVM/fLuc cells, tcyDTDO + TRAIL strongly decreased EGFR, HER2, HER3, and PDK1 levels and Akt phosphorylation, and increased PARP cleavage (Fig. 5d). These results indicate that DDAs and TRAIL cooperate to downregulate EGFR, HER3, PERK, Akt, and PDK1. Further, this downregulation correlates with the greatest degree of PARP cleavage, and these effects were reversed by caspase inhibition. In contrast, the ER stress and DR5 upregulation caused by tcyDTDO were not altered by caspase inhibition. The inability of Q-VD-OPH to overcome the ER stress response and the associated inhibition of protein synthesis and cell proliferation may explain its inability to restore cell viability to control levels. Together, the results suggest that the model in Fig. 5e operates in breast cancer cell lines, where stimulation of the TRAIL/DR5 pathway activates caspases that execute cell death in part through decreased expression of elements of the HER/PI3K/PDK1/Akt survival pathway.

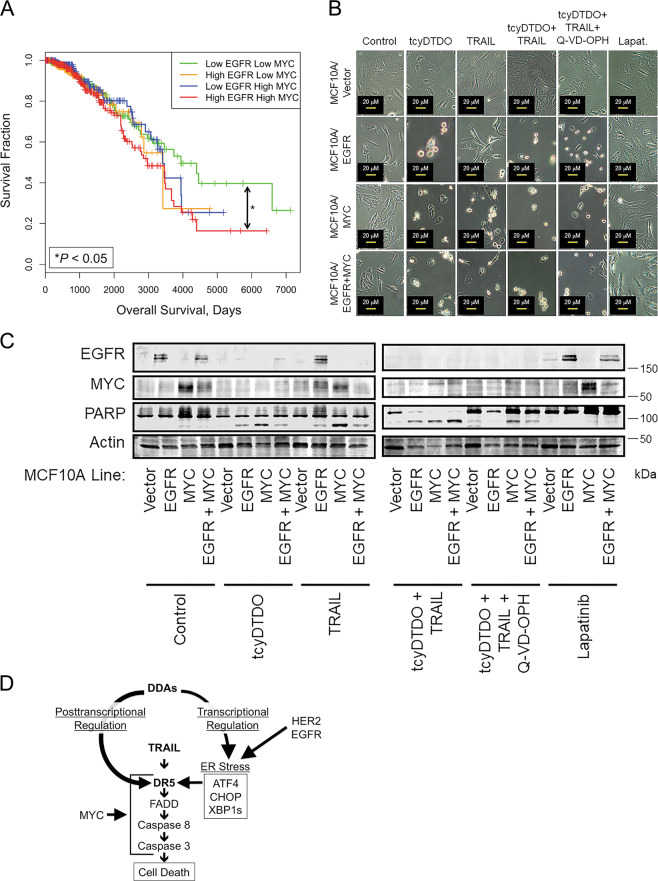

DDAs selectively kill oncogene-transformed cells

Cancer cells that overexpress EGFR or HER2 are particularly sensitive to DDAs2,4. The cancer lines chosen as representative of EGFR and HER2-overexpression, MDA-MB-468 and BT474, respectively, also exhibit MYC amplification35–37. Breast cancers with MYC and HER2 co-amplification are metastatic and exhibit a tumor initiating cell/cancer stem cell phenotype and poor prognosis38. Kaplan–Meier analyses demonstrate that breast tumors with high expression of both EGFR and MYC are likewise associated with decreased patient survival (Fig. 6a). To investigate whether overexpression of MYC increases the sensitivity of cancer cells to DDAs, we engineered MCF10A human mammary epithelial cells to overexpress EGFR, MYC, or both proteins using retroviral vectors. Photomicrographs and immunoblot analysis indicate that neither tcyDTDO nor TRAIL induced changes in cell morphology or PARP cleavage in the vector control cell line (Fig. 6b, c). In contrast, overexpression of EGFR or MYC either separately or together sensitized MCF10A cells to tcyDTDO, TRAIL, or tcyDTDO + TRAIL-induced cell death, but did not sensitize these cells to Lapatinib. The pan-caspase inhibitor Q-VD-OPH reversed the cell rounding and apoptotic morphology caused by tcyDTDO and tcyDTDO + TRAIL, but did not reverse tcyDTDO-mediated ER stress. Together, the results in Fig. 6 indicate that overexpression of either EGFR or MYC is sufficient to sensitize cells to tcyDTDO or TRAIL-mediated cell death. This is consistent with DDAs and TRAIL selectively killing oncogene-transformed cells through overlapping mechanisms, and suggest that MYC/EGFR may serve as predictive biomarkers of tcyDTDO efficacy.

Fig. 6. MYC or EGFR overexpression is sufficient to confer DDA cytotoxicity.

a Kaplan–Meier plot showing that patients with tumors overexpressing both EGFR and MYC are associated with a significantly worse survival than are patients with tumors expressing low levels of both EGFR and MYC. Patients ranked based on the expression of EGFR and MYC were classified into four groups, named “low EGFR low MYC (N = 359)”, “low EGFR high MYC (N = 220)”, “high EGFR low MYC (N = 225)”, and “high EGFR high MYC (N = 372)”. Overall survival (OS) was compared among these groups. The F test was used to compare the variance between groups (P > 0.05, ns; *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001). b Micrographs showing the morphology of the indicated MCF10A stable cell lines after 24 h of treatment with 5 µM tcyDTDO, 12.5 ng/ml TRAIL, tcyDTDO + TRAIL, tcyDTDO + TRAIL + 10 µM Q-VD-OPH, or 10 µM Lapatinib. c Immunoblot analysis of stable MCF10A cell lines treated for 24 h as in b. d Model for how DDAs activate TRAIL/DR5-induced cell death in an oncogene-dependent manner. In the context of EGFR or HER2 overexpression, DDAs elevate ER stress resulting in transcriptional upregulation of DR5. Through a second mechanism, DDAs alter DR5 disulfide bonding to promote DR5 protein stabilization, oligomerization, and activation of pro-apoptotic signaling. Cytotoxicity of DDAs and TRAIL is also potentiated in MYC-overexpressing cells.

Discussion

Great effort has been expended in testing soluble TRAIL and DR5 agonist antibodies as anticancer agents (reviewed in refs. 36,37). These trials have not demonstrated dramatic anticancer activity, due to short in vivo half-lives and trimer dissociation for soluble TRAIL agonists38–40, and the inability of bivalent agonist antibodies to trigger the same receptor trimerization induced by soluble TRAIL. DR4 and DR5 can be inactive in cancer cells due to decreased expression of the proteins41, constitutive protein internalization42–44, or alterations in post-translational modifications45–47. Potential solutions include generation of more stable trimeric forms of TRAIL48–51, and the induction of increased DR5 expression through pharmacological agents that induce ER stress to activate DR5 transcription6–9,52,53. Other strategies have included increasing DR5 half-life by decreasing its proteasomal degradation by inhibiting the proteasome23,54,55 or proteasome-associated deubiquitinases (DUBs)24. We are not aware of pharmacological approaches that: (a) cause DR5 accumulation and oligomerization, and (b) stimulate downstream caspase activation and cancer cell death through mechanisms involving altered DR5 disulfide bonding.

Our results suggest the model in Fig. 6d where DDAs activate TRAIL/DR5 signaling through two mechanisms. First, DDAs induce ER stress that is strongly potentiated by EGFR or HER2 overexpression (Fig. 1C and ref. 2), resulting in induction of the UPR and increased DR5 expression. Previous reports have shown transcriptional upregulation of DR5 by various ER stressors6–9,52,53. TcyDTDO or RBF34 upregulation of DR5 is not blocked by a PERK kinase inhibitor (GSK260641456), even though upregulation of ATF4 and CHOP is blocked (Fig. S3A). PERK inhibition does not affect tcyDTDO upregulation of GRP78 or XBP1s (Fig. S3B), so XBP1s or ATF6 may participate in DR5 upregulation in response to tcyDTDO.

Second, DDAs act distinctly from other ER stress inducers to stabilize steady-state DR5 protein levels and induce DR5 multimerization. These mechanisms may explain the ability of tcyDTDO to induce cleavage of caspases 8, 3, and PARP in the absence of TRAIL, and to potentiate the cytotoxicity of TRAIL. This is the first evidence that altering DR5 disulfide bonding favors multimerization and increased downstream signaling. A recent report showed that deletion of the extracellular domain of DR5 permits oligomerization mediated by the transmembrane domain57. Thus, the extracellular domain prevents receptor oligomerization and downstream signaling in the absence of TRAIL. The extracellular domains of DR5 and DR4 contain seven disulfide bonds (see Fig. 2f) that mediate their proper folding. We speculate that DDAs alter the patterns of DR5 and DR4 disulfide bonding to allow their oligomerization and downstream signaling in the absence of TRAIL.

DDAs are selective against cancer cells over normal cells in vitro and in vivo (herein (Fig. 6c) and elsewhere2,4). Multiple mechanisms explain the oncotoxicity of DDAs. First, DDAs selectively induce ER stress, with associated DR5 upregulation, in the context of EGFR or HER2 overexpression (Fig. 1c). Second, breast cancer cells often overexpress MYC, which strongly enhances apoptosis through the TRAIL/DR5 pathway58–61. Third, TRAIL kills cancer cells without affecting nontransformed cells11,12,35,62. Interestingly, HCI-012 lines selected for Lapatinib resistance exhibit high basal EGFR and HER2 expression, and Lapatinib treatment of these lines further elevates EGFR and HER2 levels. In addition, the resistant lines show higher MYC levels. This may explain why resistance to Lapatinib is not associated with DDA resistance.

Materials and methods

Cell culture, preparation of cell extracts, and immunoblot analysis

The cell lines MCF10A, MDA-MB-468, BT474, T47D, SW480, and DU145 were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA). The HCI-012 cell line was derived from a HER2+ patient-derived xenograft that was originally isolated from a patient as detailed previously2,27. MCF10A cells were cultured as described previously63. Unless otherwise indicated, cancer cell lines were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle’s medium (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, UT) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (10% FBS–DMEM) in a humidified 37 °C incubator with 5% CO2. Cell lysates were prepared as described previously64. Immunoblot analysis was performed by employing the following antibodies purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA) [Akt, #4691; P-Akt[T308], #13038; P-Akt[S473], #9271; ATF4, #11815; EGFR, #4267; HER2, #2165; HER3, #4754; IRE1, #3294; XBP1s, #12782; PARP, #9532; PERK, #5683; GRP78, #3177; CHOP, #2895; DR5, #8074; DR4, #42533; PDK1, #5662; Cleaved Caspase 8, #9496; Cleaved Caspase 3, #9664; MET, #3127; PERK, #9101, Rictor, #2140; MLKL, #14993; P-MLKL, #91689; PDI, #3501] and Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) [IGF-1R, sc-713; MYC, sc-764; ERK, sc-93; Actin, sc-1616-R]. P-IRE1[Ser724] (nb100-2323ss) antibody was from Novus Biologicals.

The following reagents were purchased from the indicated sources: Tunicamycin, 2-Deoxyglucose: Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO); 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB): StressMarq Biosciences (Cadboro Bay, Victoria, Canada); Thapsigargin: AdipoGen (San Diego, CA); Cycloheximide, Rapamycin: EMD Biosciences (Darmstadt, Germany); Lapatinib: Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX); Doxycycline: Enzo Life Science (Farmingdale, NY); CCF642, TORIN1, and dithiothreitol (DTT): TOCRIS Bioscience (Minneapolis, MN); Cyclosporin A (CsA): Bioryt (Atlanta, GA); LOC14, PERK Inhibitor I (GSK2606414): Calbiochem (Burlington, Massachusetts); Q-VD-OPH, Kifunensine: Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI); N-ethylmaleimide (NEM): Thermo Fisher Scientific (Grand Island, NY); MG132: InvivoGen (San Diego, CA); b-AP15: MedKoo Biosciences (Chapel Hill, NC); TRAIL: PEPROTECH (Rocky Hill, NJ).

Construction of stable cell lines using recombinant retroviruses and lentiviral shRNAs

Stable cell lines were constructed as follows: retroviral vectors encoding EGFR (Plasmid 1101165) and HER2 (Plasmid 4097866) were purchased from Addgene (Cambridge, MA). Stable MCF10A cell lines ectopically expressing EGFR, MYC, or HER2 were prepared according to the methods used in a previous report64. MYC Plasmid 17758 was obtained from Addgene67 to allow coexpression of EGFR and MYC using puromycin and zeocin selection, respectively.

T47D/Vector, T47D/EGFR, T47D/HER2, and T47D/EGFR/HER2 cell line construction was described in our previous report3,68. The HCI-012/LVM cells were isolated from mouse liver metastases using the conditional cell reprogramming approach of Schlegel and colleagues69 as detailed in a previous report2. Lapatinib-resistant sublines 012/LVM/LR5 and 012/LVM/LR10 were developed by growing HCI-012/LVM cells in the continuous presence of either 5 or 10 µM Lapatinib. Lentiviral DR5 shRNA constructs were from the TRC Lentiviral shRNA Libraries from Thermo Scientific. Labeling cells with firefly luciferase (fLuc) was performed using Addgene Plasmid 4755370. The protocol employed for developing stable cell lines with lentiviral shRNAs was from the Thermo Scientific website: https://www.thermofisher.com/us/en/home/references/gibco-cell-culture-basics/transfection-basics.

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing

Four guide RNA sequences were designed to target the human DR5 gene (GenBank accession number: AF012628) using the online CRISPR Design tool at http://crispr.mit.edu. Sequences of the four DR5 oligonucleotide pairs are as follows: 5′-CACCGAGAACGCCCCGGCCGCTTCG-3′ and 5′-AAACCGAAGCGGCCGGGGCGTTCT-3′; 5′-CACCGCCTTGTGCTCGTTGTCGCCG-3′ and 5′-AAACCGGCGACAACGAGCACAAGGC-3′; 5′-CACCGCGCGGCGACAACGAGCACAA-3′ and 5′-AAACTTGTGCTCGTTGTCGCCGCGC-3′; 5′-CACCGTTCCGGGCCCCCGAAGCGGC-3′ and 5′-AAACGCCGCTTCGGGGGCCCGGAAC-3′. Oligonucleotide pairs were annealed, phosphorylated with polynucleotide kinase, and cloned into the BsmBI site of LentiCRISPRv2 (Addgene #52961). Cloning of gRNA sequences into LentiCRISPRv2 was verified by sequence analysis. Viruses expressing the four different DR5- directed gRNAs were packaged using HEK 293T cells. To produce stable cell lines, target cell lines were subsequently infected with lentivirus and selected with 5 μg/ml puromycin, as described previously64,68. Clonal-knockout cell lines were isolated by limiting dilution and characterized by immunoblot analysis.

RT-PCR and RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted with Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen #15596-018) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Total cellular RNA was used to synthesize first-strand cDNA by using the PCR conditions listed: 25 °C for 10 min, 42 °C for 30 min, and 95 °C for 5 min. PCR was subsequently performed using either DR5 or β-actin primers. The primer sequences for DR5 are 5′- TCCACCTGGACACCATATCTCAGAA-3′ and 5′-TCCACTTCACCTGAATCACACCTG-3′ and the primer sequences for β-actin are 5′-GGATGCAGAAGGAGATCAC-3′ and 5′-AAGGTGGACAGCGAGGCCAG-3′. The PCR products were visualized on 3% agarose gels with ethidium bromide staining under UV transillumination with a digital camera system, and quantified using NIH ImageJ. Real-time qPCR was performed with the QuantStudio 6 Flex system (Thermo Fisher #4485691) using PowerUp from Invitrogen (https://www.thermofisher.com/order/catalog/product/A25742). The expression level of DR5 was normalized to β-actin, and the cycle threshold value of the sample was used to calculate the relative gene expression level = 2−(Ct target−Ct actin). The relative change in gene expression compared with the control group was expressed as fold change, and calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt method71.

Protein synthesis assays

Protein synthesis assays were carried out as detailed previously72 using 3H-Leucine (cat. # NET460001MC) obtained from Perkin Elmer (Waltham, MA).

Luciferase transcriptional reporter assays

Reporter assays were performed as described previously2 using the DR5 reporter construct obtained from Addgene (Plasmid 1601273).

Cell viability assays

Cell viability was evaluated using the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay. MTT assays were carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions (kit CGD1, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

In vivo tumor studies, histochemical, and immunohistochemical analysis

Mice were housed, maintained, and treated in the Animal Care Service Center at the University of Florida in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol number: 201608029). NOD-SCID-gamma (NSG) mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Breast cancer liver metastasis was initiated by injecting 1 × 106 cancer cells into the #4 mammary fat pads, or 200,000 cells into the lateral tail veins of adult female NSG mice.

Tissue samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS and paraffin embedded. Tissue sectioning, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, and immunohistochemical staining for 6 cleaved Caspase 3 (Cat. #9664, Cell Signaling Technology) were performed by the University of Florida Molecular Pathology Core (https://molecular.pathology.ufl.edu/).

Statistics

In Fig. 6a data obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; https://tcga.xenahubs.net/download/TCGA.BRCA.sampleMap/HiSeqV2_PANCAN.gz) [dataset ID: TCGA_BRCA_exp_HiSeqV2_PANCAN] were used to examine the relationships between tumor expression of EGFR and MYC at the mRNA level and patient survival. Gene expression data for 1176 patients with invasive breast carcinoma was measured by RNAseq and mean-normalized across all TCGA cohorts. EGFR and MYC were the two genes of interest in our study. Patients ranked based on the expression of EGFR and MYC were classified into four groups, named “low EGFR low MYC (N = 359)”, “low EGFR high MYC (N = 220)”, “high EGFR low MYC (N = 225)”, and “high EGFR high MYC (N = 372)”. Overall survival (OS) was compared among these groups. The F test was used to compare the variance between groups (P > 0.05, ns; *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001).

Statistical analyses for synergies between drugs were performed using CalcuSyn software (http://www.biosoft.com/w/calcusyn.htm). The combination index (CI) was calculated by applying the Chou–Talalay method and was used for synergy quantification74. Student’s t test was used for comparisons in both in vitro and in vivo experiments. All P values are two-tailed, and both P values and statistical tests are mentioned in either figures or legends.

Chemical syntheses of DDAs

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

These studies were supported in part by grants from the Florida Breast Cancer Foundation (B.L. and R.C.), the Ocala Royal Dames for Cancer Research (B.L.), the Florida Department of Health Bankhead-Coley Program (4BF03, B.L.), the Collaboration of Scientists for Critical Research in Biomedicine (CSCRB, Inc., B.L.), and a UF-Health Cancer Center pilot project award (B.L., R.C., and C.H.). This work was supported in part by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs through the Breast Cancer Research Program under Award Nos. W81XWH-15-1-0199 (B.L.) and W81XWH-15-1-0200 (R.C.). RBF is grateful to the University of Florida for a Graduate School Fellowship. Finally, we thank breast cancer research advocate Mrs. Jeri Francoeur for her advice and support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Ronald K. Castellano, Brian K. Law

Edited by I. Lavrik

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ronald K. Castellano, Phone: +3523922752, Email: castellano@chem.ufl.edu

Brian K. Law, Phone: +3522739423, Email: bklaw@ufl.edu

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41420-019-0228-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Costa R, et al. Targeting Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor in triple negative breast cancer: new discoveries and practical insights for drug development. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2017;53:111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferreira RB, et al. Disulfide bond disrupting agents activate the unfolded protein response in EGFR- and HER2-positive breast tumor cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8:28971–28989. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Law ME, et al. CUB domain-containing protein 1 and the epidermal growth factor receptor cooperate to induce cell detachment. Breast Cancer Res. 2016;18:80. doi: 10.1186/s13058-016-0741-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferreira RB, et al. Novel agents that downregulate EGFR, HER2, and HER3 in parallel. Oncotarget. 2015;6:10445–10459. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang M, Law ME, Castellano RK, Law BK. The unfolded protein response as a target for anticancer therapeutics. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2018;127:66–79. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu L, Su L, Liu X. PKCdelta regulates death receptor 5 expression induced by PS-341 through ATF4-ATF3/CHOP axis in human lung cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2012;11:2174–2182. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tiwary R, et al. Role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in alpha-TEA mediated TRAIL/DR5 death receptor dependent apoptosis. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11865. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdelrahim M, Newman K, Vanderlaag K, Samudio I, Safe S. 3,3'-diindolylmethane (DIM) and its derivatives induce apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells through endoplasmic reticulum stress-dependent upregulation of DR5. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:717–728. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamaguchi H, Wang HG. CHOP is involved in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis by enhancing DR5 expression in human carcinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:45495–45502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406933200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashkenazi A, Dixit VM. Apoptosis control by death and decoy receptors. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1999;11:255–260. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(99)80034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rieger J, Naumann U, Glaser T, Ashkenazi A, Weller M. APO2 ligand: a novel lethal weapon against malignant glioma? FEBS Lett. 1998;427:124–128. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00409-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffith TS, et al. Monocyte-mediated tumoricidal activity via the tumor necrosis factor-related cytokine, TRAIL. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:1343–1354. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.8.1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheong HJ, Lee KS, Woo IS, Won JH, Byun JH. Up-regulation of the DR5 expression by proteasome inhibitor MG132 augments TRAIL-induced apoptosis in soft tissue sarcoma cell lines. Cancer Res. Treat. 2011;43:124–130. doi: 10.4143/crt.2011.43.2.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.James MA, et al. A novel, soluble compound, C25, sensitizes to TRAIL-induced apoptosis through upregulation of DR5 expression. Anticancer Drugs. 2015;26:518–530. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0000000000000213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jazirehi AR, Kurdistani SK, Economou JS. Histone deacetylase inhibitor sensitizes apoptosis-resistant melanomas to cytotoxic human T lymphocytes through regulation of TRAIL/DR5 pathway. J. Immunol. 2014;192:3981–3989. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Mengxiong, Ferreira Renan B., Law Mary E., Davis Bradley J., Yaaghubi Elham, Ghilardi Amanda F., Sharma Abhisheak, Avery Bonnie A., Rodriguez Edgardo, Chiang Chi-Wu, Narayan Satya, Heldermon Coy D., Castellano Ronald K., Law Brian K. A novel proteotoxic combination therapy for EGFR+ and HER2+ cancers. Oncogene. 2019;38(22):4264–4282. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-0717-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Ping, Hu Tao, Liang Yupei, Li Pei, Chen Xiaoyu, Zhang Jingyang, Ma Yangcheng, Hao Qianyun, Wang Jinwu, Zhang Ping, Zhang Yanmei, Zhao Hu, Yang Shengli, Yu Jinha, Jeong Lak Shin, Qi Hui, Yang Meng, Hoffman Robert M., Dong Ziming, Jia Lijun. Neddylation Inhibition Activates the Extrinsic Apoptosis Pathway through ATF4–CHOP–DR5 Axis in Human Esophageal Cancer Cells. Clinical Cancer Research. 2016;22(16):4145–4157. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim MJ, et al. Ku70 acetylation and modulation of c-Myc/ATF4/CHOP signaling axis by SIRT1 inhibition lead to sensitization of HepG2 cells to TRAIL through induction of DR5 and down-regulation of c-FLIP. Int J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2013;45:711–723. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Z, et al. Activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4)-ATF3-C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) cascade shows an essential role in the ER stress-induced sensitization of tetrachlorobenzoquinone-challenged PC12 cells to ROS-mediated apoptosis via death receptor 5 (DR5) signaling. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2016;29:1510–1518. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.6b00181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cha SS, et al. Crystal structure of TRAIL-DR5 complex identifies a critical role of the unique frame insertion in conferring recognition specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:31171–31177. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004414200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mongkolsapaya J, et al. Structure of the TRAIL-DR5 complex reveals mechanisms conferring specificity in apoptotic initiation. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1999;6:1048–1053. doi: 10.1038/14935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiu CC, et al. Glucose-regulated protein 78 regulates multiple malignant phenotypes in head and neck cancer and may serve as a molecular target of therapeutic intervention. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008;7:2788–2797. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hetschko H, Voss V, Seifert V, Prehn JH, Kogel D. Upregulation of DR5 by proteasome inhibitors potently sensitizes glioma cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis. FEBS J. 2008;275:1925–1936. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oh YT, Deng L, Deng J, Sun SY. The proteasome deubiquitinase inhibitor b-AP15 enhances DR5 activation-induced apoptosis through stabilizing DR5. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:8027. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08424-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chou TC, Talalay P. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv. Enzym. Regul. 1984;22:27–55. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chou TC, Talalay P. Generalized equations for the analysis of inhibitions of Michaelis-Menten and higher-order kinetic systems with two or more mutually exclusive and nonexclusive inhibitors. Eur. J. Biochem. 1981;115:207–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1981.tb06218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeRose YS, et al. Tumor grafts derived from women with breast cancer authentically reflect tumor pathology, growth, metastasis and disease outcomes. Nat. Med. 2011;17:1514–1520. doi: 10.1038/nm.2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hitomi J, et al. Apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress depends on activation of caspase-3 via caspase-12. Neurosci. Lett. 2004;357:127–130. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.12.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamanaka RB, Bobrovnikova-Marjon E, Ji X, Liebhaber SA, Diehl JA. PERK-dependent regulation of IAP translation during ER stress. Oncogene. 2009;28:910–920. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kischkel FC, et al. Death receptor recruitment of endogenous caspase-10 and apoptosis initiation in the absence of caspase-8. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:46639–46646. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105102200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He YY, Huang JL, Chignell CF. Cleavage of epidermal growth factor receptor by caspase during apoptosis is independent of its internalization. Oncogene. 2006;25:1521–1531. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Medina EA, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-{alpha} decreases Akt protein levels in 3T3-L1 adipocytes via the caspase-dependent ubiquitination of Akt. Endocrinology. 2005;146:2726–2735. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang J, et al. Hepatitis C virus core protein activates autophagy through EIF2AK3 and ATF6 UPR pathway-mediated MAP1LC3B and ATG12 expression. Autophagy. 2014;10:766–784. doi: 10.4161/auto.27954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Livezey Mara, Huang Rui, Hergenrother Paul J., Shapiro David J. Strong and sustained activation of the anticipatory unfolded protein response induces necrotic cell death. Cell Death & Differentiation. 2018;25(10):1796–1807. doi: 10.1038/s41418-018-0143-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ashkenazi A, et al. Safety and antitumor activity of recombinant soluble Apo2 ligand. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;104:155–162. doi: 10.1172/JCI6926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kretz Anna-Laura, von Karstedt Silvia, Hillenbrand Andreas, Henne-Bruns Doris, Knippschild Uwe, Trauzold Anna, Lemke Johannes. Should We Keep Walking along the Trail for Pancreatic Cancer Treatment? Revisiting TNF-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand for Anticancer Therapy. Cancers. 2018;10(3):77. doi: 10.3390/cancers10030077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuan Xun, Gajan Ambikai, Chu Qian, Xiong Hua, Wu Kongming, Wu Gen Sheng. Developing TRAIL/TRAIL death receptor-based cancer therapies. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 2018;37(4):733–748. doi: 10.1007/s10555-018-9728-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seol JY, et al. Adenovirus-TRAIL can overcome TRAIL resistance and induce a bystander effect. Cancer Gene Ther. 2003;10:540–548. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang HH, et al. PEGylated TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) for effective tumor combination therapy. Biomaterials. 2011;32:8529–8537. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim TH, et al. PEGylated TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) analogues: pharmacokinetics and antitumor effects. Bioconjug Chem. 2011;22:1631–1637. doi: 10.1021/bc200187k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song JJ, et al. c-Cbl-mediated degradation of TRAIL receptors is responsible for the development of the early phase of TRAIL resistance. Cell Signal. 2010;22:553–563. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mert U, Sanlioglu AD. Intracellular localization of DR5 and related regulatory pathways as a mechanism of resistance to TRAIL in cancer. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2017;74:245–255. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2321-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jin Z, McDonald ER, 3rd, Dicker DT, El-Deiry WS. Deficient tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) death receptor transport to the cell surface in human colon cancer cells selected for resistance to TRAIL-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:35829–35839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405538200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Y, Yoshida T, Zhang B. TRAIL induces endocytosis of its death receptors in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2009;8:917–922. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.10.8141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoshida T, Shiraishi T, Horinaka M, Wakada M, Sakai T. Glycosylation modulates TRAIL-R1/death receptor 4 protein: different regulations of two pro-apoptotic receptors for TRAIL by tunicamycin. Oncol. Rep. 2007;18:1239–1242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liang Y, et al. N-acetyl-glucosamine sensitizes non-small cell lung cancer cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis by activating death receptor 5. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2018;45:2054–2070. doi: 10.1159/000488042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Micheau Olivier. Regulation of TNF-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand Signaling by Glycosylation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018;19(3):715. doi: 10.3390/ijms19030715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Han JH, et al. Potentiation of TRAIL killing activity by multimerization through isoleucine zipper hexamerization motif. BMB Rep. 2016;49:282–287. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2016.49.5.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lamanna G, et al. Multimerization of an apoptogenic TRAIL-mimicking peptide by using adamantane-based dendrons. Chemistry. 2013;19:1762–1768. doi: 10.1002/chem.201202415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pan LQ, et al. Engineering and refolding of a novel trimeric fusion protein TRAIL-collagen XVIII NC1. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013;97:7253–7264. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4604-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu H, et al. Improvement of pharmacokinetic profile of TRAIL via trimer-tag enhances its antitumor activity in vivo. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:8953. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09518-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang X, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress inducers, but not imatinib, sensitize Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemia cells to TRAIL-mediated apoptosis. Leuk. Res. 2011;35:940–949. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zou W, Yue P, Khuri FR, Sun SY. Coupling of endoplasmic reticulum stress to CDDO-Me-induced up-regulation of death receptor 5 via a CHOP-dependent mechanism involving JNK activation. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7484–7492. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hougardy BM, et al. A robust ex vivo model for evaluation of induction of apoptosis by rhTRAIL in combination with proteasome inhibitor MG132 in human premalignant cervical explants. Int. J. Cancer. 2008;123:1457–1465. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.He Q, Huang Y, Sheikh MS. Proteasome inhibitor MG132 upregulates death receptor 5 and cooperates with Apo2L/TRAIL to induce apoptosis in Bax-proficient and -deficient cells. Oncogene. 2004;23:2554–2558. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Axten JM, et al. Discovery of 7-methyl-5-(1-{[3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]acetyl}-2,3-dihydro-1H-indol-5-yl)-7H-p yrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-amine (GSK2606414), a potent and selective first-in-class inhibitor of protein kinase R (PKR)-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:7193–7207. doi: 10.1021/jm300713s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pan L, et al. Higher-order clustering of the transmembrane anchor of dr5 drives signaling. Cell. 2019;176:1477–1489 e1414. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ricci MS, et al. Direct repression of FLIP expression by c-myc is a major determinant of TRAIL sensitivity. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;24:8541–8555. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.19.8541-8555.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang Y, et al. Synthetic lethal targeting of MYC by activation of the DR5 death receptor pathway. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:501–512. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(04)00113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rottmann S, Wang Y, Nasoff M, Deveraux QL, Quon KC. A TRAIL receptor-dependent synthetic lethal relationship between MYC activation and GSK3beta/FBW7 loss of function. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:15195–15200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505114102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nieminen AI, Partanen JI, Hau A, Klefstrom J. c-Myc primed mitochondria determine cellular sensitivity to TRAIL-induced apoptosis. EMBO J. 2007;26:1055–1067. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wiley SR, et al. Identification and characterization of a new member of the TNF family that induces apoptosis. Immunity. 1995;3:673–682. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jahn SC, et al. Constitutive Cdk2 activity promotes aneuploidy while altering the spindle assembly and tetraploidy checkpoints. J. Cell Sci. 2013;126:1207–1217. doi: 10.1242/jcs.117382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Law BK, et al. Rapamycin potentiates transforming growth factor beta-induced growth arrest in nontransformed, oncogene-transformed, and human cancer cells. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;22:8184–8198. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.23.8184-8198.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Greulich H, et al. Oncogenic transformation by inhibitor-sensitive and -resistant EGFR mutants. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e313. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Greulich H, et al. Functional analysis of receptor tyrosine kinase mutations in lung cancer identifies oncogenic extracellular domain mutations of ERBB2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:14476–14481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203201109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dai C, Whitesell L, Rogers AB, Lindquist S. Heat shock factor 1 is a powerful multifaceted modifier of carcinogenesis. Cell. 2007;130:1005–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Law ME, et al. Glucocorticoids and histone deacetylase inhibitors cooperate to block the invasiveness of basal-like breast cancer cells through novel mechanisms. Oncogene. 2013;32:1316–1329. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu X, et al. ROCK inhibitor and feeder cells induce the conditional reprogramming of epithelial cells. Am. J. Pathol. 2012;180:599–607. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kang BH, Jensen KJ, Hatch JA, Janes KA. Simultaneous profiling of 194 distinct receptor transcripts in human cells. Sci. Signal. 2013;6:rs13. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:1101. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Law BK, et al. Salicylate-induced growth arrest is associated with inhibition of p70s6k and down-regulation of c-myc, cyclin D1, cyclin A, and proliferating cell nuclear antigen. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:38261–38267. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005545200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Takimoto R, El-Deiry WS. Wild-type p53 transactivates the KILLER/DR5 gene through an intronic sequence-specific DNA-binding site. Oncogene. 2000;19:1735–1743. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chou TC. Drug combination studies and their synergy quantification using the Chou-Talalay method. Cancer Res. 2010;70:440–446. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.