Abstract

The objective of this study was to characterize the demographics and population health of four slum communities in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, including population density and the burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases. Four urban slums were surveyed using a population-representative design between July and October 2016. A multistage cluster area random sampling process was used to identify households and individuals for the survey. Household surveys included rosters of residents, household characteristics, adult and child deaths in the past year, child health, and healthcare access and utilization. Individual surveys of two randomly sampled adults from each household included sociodemographic data, maternal health, and adult health. Additionally, blood pressure, height, weight, and psychological distress were measured by study staff. Data were weighted for complex survey design and non-response. A total of 525 households and 894 individuals completed the survey (96% household and 90% individual response rate, respectively). The estimated population density was 58,000 persons/km2. Across slums, 55% of all residents were female, and 38% were adolescents and youth 10–24 years. Among adults, 58% were female with median age 29 years (22–38). The most common adult illnesses were severe psychological distress (24%), hypertension (20%), history of physical injury/trauma (10%), asthma (7%), history of cholera (4%), and history of tuberculosis (3%). Ten percent of adults had obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2), and 7% currently smoked. The most common under-5 diseases during the last 3 months were respiratory and gastrointestinal illnesses (50% and 28%, respectively). One-third of households reported needing medical care for a child in the past year but not being able to access it, largely due to financial constraints. Unique features of these slums are a population structure dominated by adolescents and youth, a high proportion of females, and a high burden of non-communicable diseases including hypertension and psychological distress. Screening, diagnostic, and disease management interventions are urgently needed to protect and promote improved population health outcomes in these slum communities.

Keywords: Slums, Non-communicable disease, Urban health

Introduction

The number of persons living in urban slums globally is expected to double from 881 million to 2 billion persons in the next 30 years, and yet there is a paucity of health data from these settings [1, 2]. Urban slums are particularly vulnerable environments for poor health outcomes given the convergence of inadequate sanitation, clean water, and electricity coupled with overcrowding, food insecurity, violence, and the lack of health systems [2, 3]. It is essential to monitor the health status of urban slum communities in order to develop health prevention and treatment interventions. Up-to-date data on slum living conditions also can inform progress towards the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 11, which aims to make cities safe and healthier [4].

Haiti is the poorest country in the Americas, ranking 163 out of 187 on the 2016 Human Development Index [5]. Haiti has undergone rapid urbanization with the share of the population living in urban areas increasing from 21% in 1980 to 59% in 2015 [6, 7]. Additionally, 74% of Haiti’s urban population is estimated to live in slums compared to 56% in sub-Saharan Africa and 21% in the Latin America and Caribbean region [4, 6, 7].

Of Haiti’s estimated 11 million citizens, approximately three million live within the metropolitan area of the capital city, Port-au-Prince, and 2.2 million of those in slums [8]. In the 1950s, many of the coastal areas of downtown Port-au-Prince lapsed into slums characterized by lack of sanitation, clean water, and electricity as well as overcrowding, food insecurity, and violence. Historically, these communities were also sites of gang violence that further limited the influx of municipal services including police and health [9, 10]. In January 2010, a devastating earthquake left over 1.5 million Haitians homeless, leading approximately 279,000 people from outside Port-au-Prince to relocate into tent camps adjacent to these slum communities [11–13]. Most residents of the camps subsequently moved into these slum areas [14]. No published demographic studies or general health surveys have previously targeted these slum areas.

The objective of this study was to characterize the demographics and population health of these slum communities, including burden of communicable (CD) and non-communicable diseases (NCD), and healthcare utilization, in order to inform local health promotion, prevention, and treatment programs.

Methods

Setting and Study Population

GHESKIO (Haitian Group for the Study of Kaposi’s Sarcoma and Opportunistic Infections) is a non-governmental organization located in downtown Port-au-Prince, directly adjacent to the city’s coastal slum communities. GHESKIO was founded in 1982 and is the largest provider of integrated services for HIV and tuberculosis in Haiti. Over the past 35 years, GHESKIO has provided community health interventions in these slum communities including HIV testing, tuberculosis screening, and cholera vaccination [15–17]. The study population includes 4 slums: Village de Dieu, Cité Plus, Cité l’Eternel, and Martissant Littoral (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Aerial map of surveyed areas (DigitalGlobe Foundation)

Study Design

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of randomly selected households and individuals living in the selected slum communities. Households were selected based on cluster area random sampling. Each community was divided into blocks that had an estimated population count based on data from a prior GHESKIO survey and online high-resolution images [18]. We created 111 geospatial waypoints, with the number of waypoints per block proportional to its estimated population. ArcGIS was used to randomly generate the waypoints with corresponding global positioning system (GPS) software within each block; commercial buildings and empty spaces were excluded. For each waypoint, community health workers (CHWs) followed a protocol to identify the closest five households.

Households were defined as a person or persons, related or unrelated, who live together in a residential structure, make common provisions for food, and regularly take their food from the same pot [19]. One residential structure could contain multiple households. Up to three attempts were made to conduct the household interview, targeting eligible household members who were ≥ 18 years and slept in the household in the past two nights. Verbal consent was collected from eligible household members, who would jointly complete the household survey with the interviewer.

At the end of the survey, two eligible adult household members were randomly selected to participate in the individual survey. In households with fewer than 2 adult residents, only one adult resident was invited to participate without random selection. Up to three attempts were made to interview selected individuals, and a new verbal consent was obtained from participants for the individual survey.

Data Collection

Prior to survey administration, GHESKIO staff presented the study to community leaders to sensitize communities. Twenty-seven CHWs, the majority of whom resided in these communities, received 2 weeks of training on study recruitment, consent, survey administration, and collection of anthropometrics in the field.

Household surveys were paper-based and included data on living conditions, water and sanitation, number of persons living in each household (defined as adults who slept in the household at least once in the past 2 nights and children who lived in the household in the past month), adult and child mortality over the preceding year, and child health (5 years or younger, for up to 2 randomly selected children in each household).

Individual surveys were administered on an electronic tablet and included sociodemographic characteristics, migration history, self-reported symptoms and diagnoses of CD and NCDs, maternal health, health access and utilization, and food security. Family planning questions included use of condoms, oral or injectable contraception, or other methods. Psychological distress was measured using the Kessler-6 scale, which has been validated in multiple resource-limited settings [20]. At the end of the survey, anthropometrics (height, weight with body mass index (BMI) (kilograms/m2)) and blood pressure were collected by the CHW. Blood pressure was measured three times on the left arm using an electronic cuff with 3 cuff sizes (Panasonic model EW3109W) after each participant was seated for a minimum of 15 min [21, 22].

At the completion of the survey, blood pressure and anthropometric readings were provided on a card to participants. Participants were provided basic information about hypertension and referred for free re-screening and medical care to GHESKIO. Participants with any systolic reading ≥ 180 mmHg were encouraged to visit the clinic on the same day.

Household survey questionnaires were double-entered into a secured electronic database at GHESKIO. All data were de-identified for cleaning and analysis.

Variable Definitions

Hypertension was defined using the average of the last 2 of 3 blood pressure measurements, as systolic blood pressure (SBP) > 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) > 90 mmHg, or self-reported use of anti-hypertensive medication prescribed by a clinician, per JNC-VII [23]. Stage 1 hypertension was SBP > 140 mmHg or DBP > 90 mmHg and stage 2 hypertension was SBP > 160 mmHg or DBP > 100 mmHg [21, 23]. BMI was categorized as underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal (18.5–< 25 kg/m2), overweight (25–< 30 kg/m2), and obese (≥ 30 kg/m2) [24].

Severe psychological distress was defined as Kessler-6 scores above the cutoff of 13 points [20, 25]. This score has been previously used in over 30 countries as well as for Haitian immigrants living in the USA [26]. Smoking status was self-reported as current smoking on some or all days. Frequency of alcohol use was self-reported as never, monthly or less, 2–4 times a month, 2–3 times a week, or 4 or more times a week. To assess diet, respondents were asked how many days in a typical week they eat fresh fruit and vegetables (for analysis, the mean of both numbers was used), how many times per day they ate fried foods, and how often they added salt to food.

Adult and child mortality rates were estimated by totaling the reported adult/child deaths in the year prior and dividing by the sum of deaths and living residents reported on the household rosters. No data were available for temporary residents over the prior year or person-time of residence.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were weighted to account for complex survey design and non-response. Weights were constructed for each section of the survey whose participants were randomly selected: (1) households (household survey), (2) adults (individual survey), and (3) children ≤ 5 years old (child health portion of the household survey). Weights accounted for prior population estimates and probabilities of selection (within each block, waypoint, and building) and of survey completion (calculated within slum and block strata, as well as sex and age group strata in the individual survey). Additionally, post-stratification weights were applied to the individual adult survey sample to match the weighted sex and age distribution of adults listed in the household rosters.

A population estimate was obtained by multiplying the average number of people per structure in each block with the number of structures in that block. A population pyramid was constructed from weighted household member data and graphically compared with the Haiti population distribution [27]. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize households and individuals participating in the survey. All estimates were stratified across the four sampled slums. Hypertension prevalence was age-standardized to the world population using the 2000–2025 WHO standard population data [28].

Ethics

This study was approved by institutional review boards at Weill Cornell Medicine, City University of New York, University of Minnesota, and the Ethics Board at GHESKIO.

Results

Survey Population

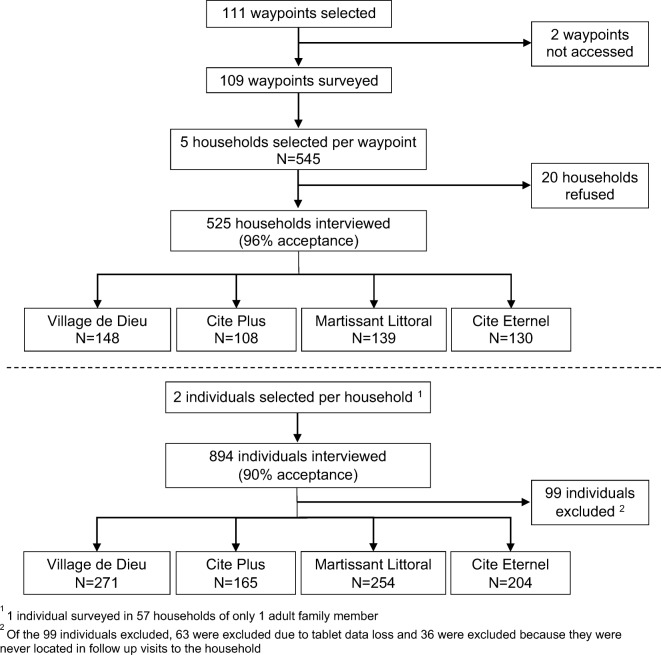

A total of 109 of 111 (98%) waypoints and 525 of 545 households (96%) were surveyed from July 25 to October 26, 2016 (Fig. 2). Reasons for household non-response included 7 refusals, 9 households not reached after repeated attempts, 2 households moved, and 2 households could not be surveyed due to violence in the area. Among 993 individuals randomly selected from the 525 households, 894 (90%) were surveyed between September 31 and October 26, 2016.

Fig. 2.

Survey recruitment flowchart (MSPowerpoint)

We estimate the population of the four slums to be 55,622 inhabitants (95% CI 34,517–76,726), covering a geographic area of 0.96 km2, with estimated population density of 58,000 people/km2.

Household Characteristics

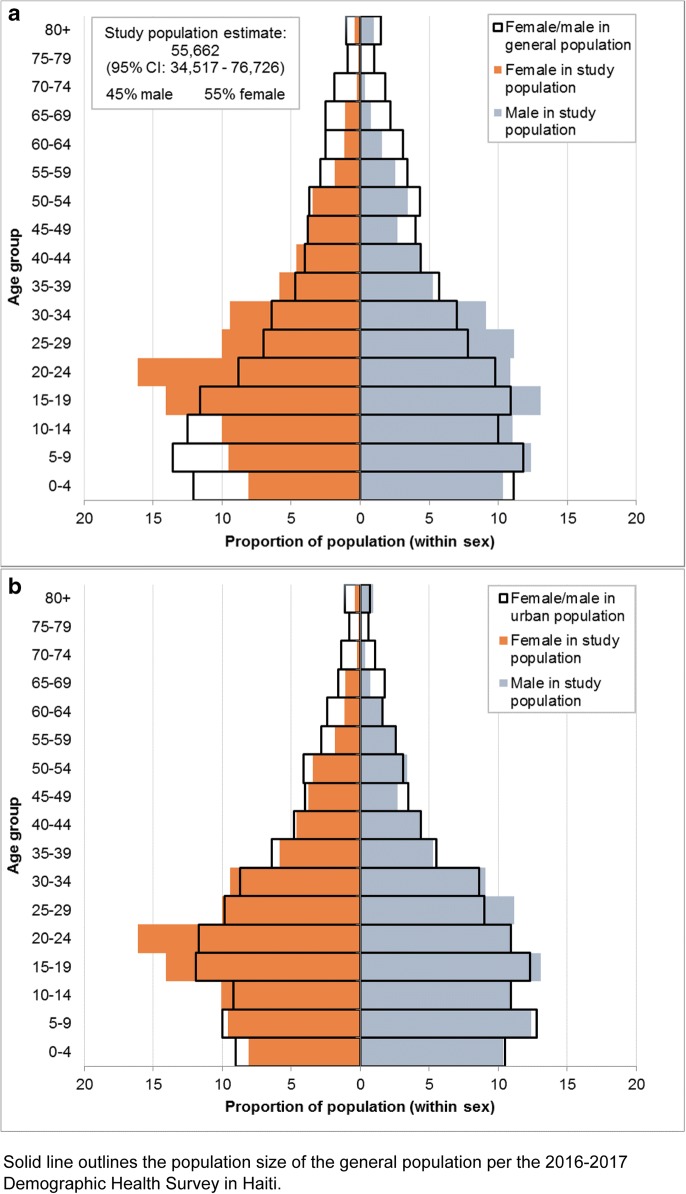

Figure 3 illustrates the age sex pyramid of the surveyed slum population and compares it with the 2016–2017 general population from the Demography Health Survey (DHS) of Haiti [27]. Fifty-five percent of the population was female, with 20% children under 10 and 38% adolescents and youth 10–24 years (Table 1). Among adults 18 years or older, median age was 29 years (IQR 22–39). On average, each household included 2 adults and 1 child, and 9% of households included a pregnant woman. Sixteen percent of households had no adult men. Six percent of households responded that other adults had lived in the household in the preceding months but had not slept there in the past two nights.

Fig. 3.

a Slum population age structure compared to overall Haitian population structure. b Slum population age structure compared to overall Haitian urban population structure (MSExcel)

Table 1.

Household characteristics

| Denominator (households) | N (weighted %) or median (IQR) | Range across slums | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of households in building: median (IQR) | 525 | 1 (1, 2) | 1–1 |

| Number of people in building: median (IQR) | 525 | 5 (3, 8) | 4–7 |

| Number of adults who slept in household in past 1–2 nights: median (IQR) | 525 | 2 (1, 3) | 2–2 |

| Number of children under 18 who live in HH: median (IQR) | 525 | 1 (0, 2) | 1–1 |

| A pregnant woman slept in household in past 1–2 nights or a pregnant girl lived in the household in the past month | 525 | 44 (9%) | 5–13% |

| Resident age* (N = 2365 residents) | 525 | ||

| Overall: median (IQR) | 21 (12–32) | 20–21 | |

| Child/adolescent < 18 years old: median (IQR) | 8 (4–13) | 6–9 | |

| Adult ≥ 18 years old: median (IQR) (N = 1517 residents) | 29 (22–39) | 27–30 | |

| 0–9 | 471 (20%) | 18–22% | |

| 10–19 | 543 (24%) | 22–27% | |

| 20–24 | 341 (14%) | 13–16% | |

| 25–40 | 652 (27%) | 26–29% | |

| 41–60 | 296 (12%) | 11–15% | |

| > 60 | 62 (3%) | 2–4% | |

| Resident sexa | 525 | ||

| Overall (N = 2365 residents) | |||

| Male | 1082 (45%) | 43–47% | |

| Female | 1283 (55%) | 53–57% | |

| Adult ≥ 18 years old (N = 1517 residents) | |||

| Male | 665 (42%) | 39–44% | |

| Female | 852 (58%) | 57–61% | |

| Child/adolescent < 18 years old (N = 848 residents) | |||

| Male | 417 (51%) | 46–53% | |

| Female | 431 (49%) | 47–54% | |

| General household characteristics | |||

| Main material of dwelling: cement | 525 | 495 (95%) | 93–100% |

| Main source of drinking water | 525 | ||

| Tap inside house | 26 (4%) | 2–9% | |

| Tap outside house | 303 (60%) | 55–68% | |

| Bottled or treated water | 192 (36%) | 29–39% | |

| Other | 4 (<1%) | 0–1% | |

| Actions taken to make water safe to drink (not mutually exclusive) | |||

| Boiling | 14 (3%) | 1–7% | |

| Using bleach or chlorine | 317 (62%) | 47–67% | |

| Straining through cloth or filter | 4 (1%) | 0–2% | |

| Using a dedicated bucket only for drinking water | 23 (4%) | 0–18% | |

| Drinking only bottled water | 75 (12%) | 5–18% | |

| Nothing | 100 (19%) | 10–26% | |

| Availability of electricity | 525 | ||

| Always | 131 (24%) | 9–42% | |

| Sometimes | 350 (67%) | 44–87% | |

| Never | 44 (9%) | 4–14% | |

| Has mosquito net | 523 | 179 (34%) | 23–43% |

| Cooks mainly on charcoal or fire | 524 | 493 (96%) | 93–98% |

| Cooks indoors | 516 | 322 (67%) | 54–75% |

| Sanitation | |||

| Pit toilet | 522 | 406 (74%) | 59–92% |

| Flush toilet | 94 (22%) | 8–31% | |

| Bucket, bag, stream, or other outdoor | 22 (5%) | 0–14% |

aSex and age as reported on household rosters, and corrected if reported to be different during individual interviews (among adults randomly selected for individual interviews)

The main dwelling material was cement (95%). Over a third (36%) of households used bottled or treated water as the primary source for drinking, with only 4% of households having an indoor water source. Sixty-two percent reported using bleach or chlorine to make water safe to drink (Table 1). Electricity was available for the majority (91%) of households. Most households cooked indoors (67%) using charcoal or fire (96%) and 74% mainly used a pit latrine. Only 34% of households had a mosquito bed net available.

Individual Characteristics

Among adults, 36% had no schooling or only primary-level schooling (Table 2). Approximately half were married. Over a third were unemployed (including students) and the most common occupation was selling goods or food. Forty percent reported no income and 79% owned a mobile phone.

Table 2.

Characteristics of adult residents (N = 894) living in slum communities

| Denominator (individuals) | N (weighted %) or median (IQR) | Range across slums | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | |||

| Sex | 894 | ||

| Male | 350 (42%) | 33–53% | |

| Female | 544 (58%) | 47–67% | |

| Age | 894 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 28 (22–39) | 27–30 | |

| Highest level of education attended | 893 | ||

| None | 68 (7%) | 4–11% | |

| Primary | 286 (29%) | 21–37% | |

| Secondary | 461 (54%) | 46–66% | |

| Higher | 78 (10%) | 6–15% | |

| Marital status | 894 | ||

| Married/cohabiting | 427 (45%) | 36–52% | |

| Single | 370 (45%) | 32–58% | |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 97 (10%) | 5–16% | |

| Occupation | 891 | ||

| Does not work for pay (including students) | 324 (41%) | 24–55% | |

| Construction or mechanic | 107 (14%) | 5–21% | |

| Sells goods or food | 292 (28%) | 23–33% | |

| Professional job (that went to university for) or teacher | 78 (8%) | 6–11% | |

| Services and other | 90 (9%) | 7–10% | |

| Income earned per daya | 871 | ||

| None | 308 (40%) | 21–52% | |

| < 0.75 USD | 59 (7%) | 4–9% | |

| 0.75–1.50 USD | 119 (11%) | 5–18% | |

| > 1.50 USD | 385 (42%) | 32–62% | |

| Owns a mobile phone | 893 | 694 (79%) | 73–83% |

| Migration | |||

| Time in current neighborhood | 893 | ||

| < 1 year | 137 (15%) | 9–18% | |

| 1–3 years | 244 (25%) | 12–41% | |

| > 3 years but not entire life | 230 (28%) | 6–39% | |

| Entire life | 282 (32%) | 11–64% | |

| Main reason for move to current neighborhoodb | 610 | ||

| To live with family/friends | 208 (34%) | 27–40% | |

| Problem with previous housing (e.g., cost, eviction, land or utility problems)—unprompted | 92 (14%) | 9–17% | |

| Violence in previous neighborhood | 77 (12%) | 10–18% | |

| Education | 67 (11%) | 9–14% | |

| Work | 59 (11%) | 8–21% | |

| Considers another place home | 894 | 462 (50%) | 38–56% |

aCalculated as 1 Haitian Gourde = 0.015 USD; corresponds to categories: < 50 gourdes, 50–100 gourdes, > 100 gourdes

bAmong those who ever moved

Approximately a third (32%) of adults reported living in the slum for his/her entire life, ranging from 11% in Martissant Littoral to 64% in Village de Dieu. Among ever-migrants, the main reason for moving to the slum was to live with friends and family (34%), followed by violence in prior neighborhood, education and employment opportunities, and displacement from the earthquake. Half of residents considered another place home.

Adult Health

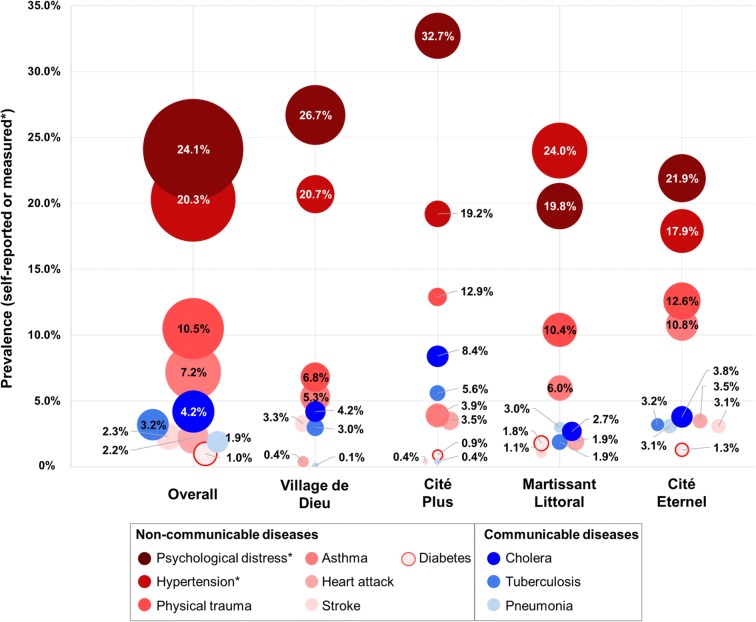

The most common surveyed NCDs were severe psychological distress (24% overall, with neighborhood range 20–33%), hypertension (20%, range 18–24%), history of physical trauma (10%, range 7–13%), and asthma (7%, range 4–11%) (Fig. 4, Table 3). Age-standardized prevalence of hypertension was 29%. Median SBP was 117 mmHg (IQR 108–129) and DBP 72 mmHg (IQR 65–83). Among the persons with hypertension per blood pressure measures on the day of survey, 67% had stage 1 and 33% had stage 2. Cardiovascular risk factors include overweight/obesity (37%), current smoking (7%), prior diagnosis of diabetes (1%), housing with indoor cooking (67%), and frequent consumption of salt (33%) and of fried food (69% at least once per day).

Fig. 4.

Prevalence of adult communicable and non-communicable diseases (MSExcel)

Table 3.

Adult mortality, health status, and risk factors

| Denominator | N (weighted %), median (IQR), or rate | Range across slums | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult mortality | |||

| Housholds that experienced an adult death in past year | 525 | 17 (3%) | 1–7% |

| Approximate adult death rate over past year | 1537a | 10.6/1000 | 2.7–27.9 |

| Self-reported diseases in lifetime | |||

| Non-communicable disease (NCD) | |||

| Stroke | 894 | 16 (2%) | 0–3% |

| Heart attack | 894 | 23 (2%) | 0–3% |

| Diabetes | 893 | 14 (1%) | 0–2% |

| Asthma | 894 | 73 (7%) | 4–11% |

| Cancer | 893 | 0 (0%) | N/A |

| Physical injury/trauma | 894 | 87 (10%) | 7–13% |

| Communicable disease (CD) | |||

| Pneumonia | 892 | 13 (2%) | 0–3% |

| Tuberculosis | 894 | 23 (3%) | 2–6% |

| Cholera | 892 | 41 (4%) | 3–8% |

| Hepatitis | 893 | 1 (0%) | 0–< 1% |

| Cancer | 894 | 0 (0%) | N/A |

| Diseases and health behaviors documented at time of survey | |||

| Mental health | |||

| Kessler-6 psychological distress score: median (IQR) | 892 | 10 (7–12) | 9–11 |

| Kessler-6 severe psychological distress | 892 | 235 (24%) | 20–33% |

| Hypertension | |||

| Systolic blood pressure: median (IQR) | 886 | 117 (108–129) | 111–120 |

| Diastolic blood pressure: median (IQR) | 886 | 72 (65–83) | 70–76 |

| Any hypertension (as measured or on prescribed treatment) | 886 | 179 (20%) | 18–24% |

| Hypertension stage 1 | 108 (13%) | 11–16% | |

| Hypertension stage 2 | 53 (6%) | 4–8% | |

| Body mass index | 874 | ||

| Underweight (< 18.5) | 78 (9%) | 7–16% | |

| Normal (18.5– < 25) | 462 (54%) | 50–61% | |

| Overweight (25– < 30) | 232 (27%) | 17–30% | |

| Obese (≥ 30) | 100 (10%) | 6–13% | |

| Smoking | 894 | ||

| Every day or some days | 68 (7%) | 6–11% | |

| Previously | 50 (4%) | 1–6% | |

| Never | 776 (89%) | 84–93% | |

| Alcohol consumption | 894 | ||

| At least twice a week | 148 (18%) | 16–27% | |

| At least twice a month | 172 (20%) | 13–25% | |

| Never or monthly or less | 574 (62%) | 49–70% | |

| Diet | |||

| At least 1 fried meal per day | 892 | 606 (69%) | 55–73% |

| Often or always uses salt in food | 887 | 262 (33%) | 6–60% |

| Mean number of days/week eats fresh fruit/vegetables: median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 1–2 | |

| Number of days drinks soda / sweetened beverages per week: median (IQR) | 894 | 2 (0–6) | 1–3 |

| Women’s healthb | |||

| Currently using any birth control method (if sexually active) | 495 | 198 (38%) | 23–49% |

| Ever pregnant | 539 | 360 (62%) | 58–71% |

| Has had 5 or more pregnancies | 539 | 53 (5%) | 4–13% |

| Last live birth delivered in a hospital | 336 | 191 (56%) | 41–62% |

| Any antenatal care for the last pregnancy | 335 | 288 (86%) | 83–88% |

| Healthcare access and utilization | |||

| Ever received cholera vaccine | 892 | 214 (26%) | 15–35% |

| Sought medical care in past year | 893 | 304 (36%) | 27–44% |

| Hospitalized in past year | 893 | 46 (5%) | 2–9% |

| Cost to travel to clinic (one way), USDc,d | 303 | 0.21 (0–0.69) | 0.09–0.35 |

| Time to get to clinic (one way), minutesd | 304 | 19 (10–30) | 14–27 |

| Did not receive care that was needed in the past 6 months | 894 | 235 (26%) | 21–35% |

| Ever gone without healthcare to afford food | 894 | 221 (27%) | 18–37% |

aCombines number of living adults listed on household rosters and deaths reported for the past year

bAmong women (N = 544)

cCalculated as 1 Haitian Gourde = 0.015 USD; corresponds to median (IQR) of 14 (0–46) and range of medians of 6–23

dAmong those who sought care in the past year (N = 304)

The most common self-reported lifetime CDs were history of cholera (4%), tuberculosis (3%), and pneumonia (2%). There was 1 reported case of diagnosed hepatitis and no diagnoses of cancer.

Women’s Health

Among women, 62% reported a pregnancy in their lifetime. Of these women, 56% reported last live birth delivered in a hospital and 86% reported any antenatal care for the last pregnancy (Table 3). Among those reporting to be currently sexually active, 38% used any family planning method.

Child Health

The most common reported illnesses among children ≤ 5 years in the past 3 months included cough or respiratory diseases (50%) and gastrointestinal illness (28%). A third (34%) reported fever and 47% reported cough in the past 2 weeks (Table 4).

Table 4.

Child mortality and health status

| Denominator | N (weighted %) or rate | Range across slums | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child mortality (0–17 years old) | |||

| HH experienced a child death in past year | 525 | 7 (1%) | 1–1% |

| Approximate child death rate over past year | 855a | 6.3/1000 | 3.5–8.5 |

| Child health (≤5 years old) | |||

| Diagnoses and symptoms in past 3 monthsb | |||

| Tuberculosis | 266 | 0 (0%) | N/A |

| Cough or respiratory disease other than tuberculosis | 266 | 123 (50%) | 28–64% |

| HIV | 266 | 0 (0%) | N/A |

| Cholera | 266 | 3 (1%) | 0–1% |

| Malaria | 266 | 4 (2%) | 0–2% |

| Intestinal worms | 266 | 48 (21%) | 6–36% |

| Gastrointestinal illness (diarrhea/vomiting) | 266 | 71 (28%) | 12–40% |

| Symptoms in past 2 weeksb | |||

| Fever | 264 | 90 (34%) | 26–44% |

| Cough | 265 | 111 (47%) | 26–64% |

| Health access and utilization | |||

| Child ever received a vaccineb | 263 | 247 (93%) | 88–98% |

| Child ever received a cholera vaccineb | 257 | 71 (26%) | 18–36% |

| Household sought medical care for a child in past yearc | 217 | 108 (52%) | 29–67% |

| Child in household hospitalized in past yearc | 219 | 21 (14%) | 4–21% |

| Child in household needed medical care, but did not get itc | 196 | 53 (30%) | 10–41% |

| Main reasons for not finding cared | |||

| Inability to afford care | 53 | 26 (43%) | N/A |

| Inability to afford transportation | 53 | 10 (13%) | N/A |

| Work during health center’s opening hours | 53 | 4 (7%) | N/A |

aCombines number of living children listed on household rosters and child deaths reported for the past year

bAmong 266 randomly selected children aged ≤ 5 years old

cAmong all households with children aged ≤ 5 years old (N = 219)

dAmong households that did not get needed medical care for a child aged ≤ 5 (N = 53)

Mortality Estimates

An adult (≥ 18 years) death in the past year was reported by 3% of households (range 1–7% across slums) with an estimated annual mortality rate of 10.6 deaths/1000 adults (range 4.4–27.9/1000 across slums). The proportion of households which reported a child (< 18 years) death in the past year was 1% (range 1–1% across slums) with an estimated mortality rate of 6.3 deaths/1000 children ≤ 18 years (range 3.5–8.5/1000 across slums).

Health Access and Utilization

Approximately a third (36%) of adults sought medical care in the past year and median cost to travel to clinic was approximately 20 cents USD/one way (Table 3). A quarter reported not receiving care in the last 6 months when it was needed and had ever foregone healthcare to afford other necessities such as food. Among households with children ≤ 5 years old, 52% sought medical care for a child in the past year (Table 4). Thirty percent of households reported a child in their home needed care but could not get it, with the most common reason being inability to afford care (Table 4).

Discussion

This study presents population-representative survey data on the demographics and burden of diseases in four urban slum communities in Haiti that have not been systematically included in prior health surveys. Key findings include a population structure predominated by adolescents and youth, a high proportion of females, and a high prevalence of hypertension and mental distress. These findings underscore the importance of implementing public health interventions targeting adolescent health and chronic diseases in slum communities.

Our slum population estimate of 55,622 compares to 60,852 residents that were counted in these slum communities for a cholera vaccination study in 2013 [17]. The population density of 58,000 persons/km2 surpasses the density of Dhaka, Bangladesh, the world’s most crowded city, with 44,500 persons/km2, yet is lower than the population densities of the largest slums in India and Africa which have as many as 200,000 persons/km2 [29, 30]. It is also greater than the average population density of Port-au-Prince of 25,000 persons/km2 [31]. The average household size in our survey (3 persons—2 adults and 1 child) was smaller than other slum studies of 4.7 person in India slums in the 2011 census [32] and 5 persons in the Kibera slum of Kenya in 2009 [30]. It was also smaller than the average household of 4.3 persons reported by the 2016–2017 Demographic Health Survey (DHS) of Haiti [27]. This may reflect that our survey only includes persons who slept in the household at least one of the most recent two nights.

These slums, compared to Haiti nationally, have a higher proportion of adolescents and youth ages 10–24 (38% versus 32% across Haiti) and fewer children ages 0–9 (20% versus 24% across Haiti) [27]. The differences, albeit narrower, persist when the slum communities are compared to urban Haiti (Fig. 3b). However, the population structure of the slum communities is similar to a 2000–2002 demographic study of four slums in Kenya, with a high concentration of young adults and a lower than expected proportion of children than is typical of expansive population pyramids of most developing countries [33].

The second notable finding is the large proportion of females in these slum communities. The ratio of males to females in our survey (82:100) is similar to the 2016–2017 DHS estimate for urban Haiti (84:100) [34]. This ratio appears unchanged from the 1980 United Nations estimate of 82:100 for urban areas in Haiti [7] and is consistent with women outnumbering men across much of urban Latin America [7, 35]. In contrast, however, slum studies from Kenya and India report a higher proportion of males [33, 36]. In our survey, the skewness of slum sex ratio is especially acute among adolescents and young adults where the ratio of males to females is 71:100. Additionally, 16% of the households surveyed contained only females. While there is no national statistic for comparison, the 2016–2017 DHS reported 45% of household were headed by women [27].

Factors influencing the age and sex composition of these slum communities include migration and natural increase [37]. In the case of Haiti, and many other Central American and Caribbean countries, rural to urban migration is the main driver of the skewed sex and age composition [35, 38]. Based on analysis of the most recent Haitian census in 2003, 19% of the male population and 24% of the female population had migrated at some point in their life for a ratio of 79:100 male to female [39]. For residents of Port-au-Prince, migrant status peaks between the ages of 20–24 for both men and women; however, there are more female migrants at every age group [39]. Another contributing factor for skewed sex ratio could be that our study population includes only persons who slept in the home in the past 1–2 nights, which could bias the results if men are more likely to travel or sleep in other areas during the work week. Finally, we do not have prior data to compare the demographics of these communities prior to the 2010 earthquake but many displaced families with young children may have moved into the slums after the event and now many of these children would be teenagers.

A third finding of this survey was the large burden of NCDs, which are increasingly recognized as a “neglected epidemic” in slum communities [3, 40]. Chronic diseases account for 72% of the total global burden of disease in adults, with 80% occurring in low- and middle-income countries [41]. Among NCDs assessed by this survey, hypertension and mental distress were the most prevalent, affecting 20% and 24% of the adult population, respectively.

Cardiovascular disease is now the leading cause of adult mortality in Haiti, accounting for an estimated 27% of deaths in 2016, and hypertension is the most common cardiovascular disease risk factor [42]. The Haiti 2016–2017 DHS reported that hypertension rates were 49% and 38% for urban women and men ages 35–64 years, respectively, which are higher than the rates for this age group in our survey (35% and 36%, respectively) [34]. In contrast, our age-standardized prevalence of hypertension (29%) is slightly higher than prevalence reported for slum communities elsewhere [43–46]. For example, age-standardized hypertension prevalence was 18% among a random sample of adults residing in two slums in Kenya [44], 21% (not age adjusted) in a slum study in Brazil [46], and 17–23% among adults living in slums in India [47]. Detailed analysis of hypertension findings from this survey including risk factors associated with hypertension has been previously reported [22].

Interestingly, the traditional risk factors for hypertension such as obesity, diabetes, and smoking were low in our survey—10%, 7%, and 1%, respectively. Possible poverty-related social and environmental factors that may be contributing to high rates of hypertension and cardiovascular disease include social isolation, stress, depression, food insecurity and diet, and environmental exposures (e.g., lead, indoor air pollution) [22, 48–52]. Understanding the drivers of hypertension in these communities will help inform future prevention interventions.

We also found high rates of mental distress in this population. Severe psychological distress was 24%, as measured using the Kessler-6 screening tool. Two studies from Port-au-Prince after the 2010 earthquake reported prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder ranging from 25 to 37% and depression as high as 42% [53–55]. Our findings are similar to other studies reporting a high burden of mental illness in urban slums in countries such as India, Ghana, and Pakistan [56–58]. Prior research has reported associations between slum residence and greater risk of mental health problems, for example, stress arising from traumas frequent in informal, crowded settlements (e.g., forced eviction, fires, violence) [59–61]. Poor housing conditions and flood risk can also contribute to poor mental health status in slum communities, highlighting the importance of further inquiry into routine mental health needs of slum residents, outside of the context of natural disasters [62].

It is important to contextualize the environmental and health conditions of these slum communities to the conditions of Port-au-Prince and Haiti overall. Direct comparisons are limited given differences in survey questions and age groups of participants across studies. The most significant difference of the surveyed slum communities is their population density, which is approximately double of other Haitian urban areas, as discussed above. Access to potable drink water appears similar between the slums and urban Haiti [27]. The slums lack sewer systems and 20% of households report a flush toilet that drains into a hole or canal. In contrast, 43% of adults in urban areas report “improved sanitation” which includes a flush toilet that drains into a septic hole, tank, or system [27]. The rate of no school or primary-level education is 36% among slum residents in our study which falls between urban and rural residents in Haiti, 57% and 28%, respectively, as measured among adults ages 15–49 who reported no school, incomplete, or completion of primary school [27]. In our survey, 93% of children up to 5 years old had received at least one vaccine (unspecified). An indirect comparison is that 41% of infants ages 12–23 months received all vaccines in Haiti in 2016–2017 [27]. Of note, among 24–35-month-old children countrywide, the proportion with at least one of the core vaccines (Bacille Calmette-Guérin, polio, diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis, rotavirus, measles) was 89% in 2016–2017 [27].

Strengths of this study include a population-representative sample which increases the generalizability of study findings to other residents living in these communities. Secondly, we used a standard blood pressure measurement protocol that allows comparison to other studies. Limitations include the use of self-reported information on disease history and mortality, and restriction of the study population to those who slept in the household in the prior two nights. Our mortality rates may be overestimated, as we do not have an accurate denominator of all persons who lived in the study households over the prior year. We also do not have causes of death. Additionally, our selected measures for health behaviors may miss patterns of at-risk behaviors such as intermittent drinking and smoking, for example. The survey was also not able to screen for infectious diseases due to stigma of community-based HIV testing and lack of serologies for prior exposure to many infections. We relied on self-reported data on infectious disease history for TB, cholera, and symptoms. Altogether, our data underscores the challenging double-burden of infectious and non-infectious diseases in slum communities.

Conclusion

In summary, this study provides insights on the demographics and population health of four slum communities in Port-au-Prince that have not been historically included in systematic health monitoring. Main findings include a population structure dominated by female adolescents and young adults and high rates of hypertension and mental distress. Additional research is needed to understand the drivers of NCDs in this community to design interventions aimed at adolescent health services and chronic disease prevention and treatment.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by funding from the following: NIH Fogarty 3D43TW009606-03S1, D43TW009337; NHLBI R01HL143788; NIAID K24AI098627, and NICHD R24HD041023.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This study was approved by institutional review boards at Weill Cornell Medicine, City University of New York, University of Minnesota, and the Ethics Board at GHESKIO.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.UN-Habitat The challenge of slums: global report on human settlements 2003. United Nations-Habitat. 2004;15(3):337–338. [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Lancet Health in slums: understanding the unseen. Lancet (London, England) 2017;389(10068):478. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riley LW, Ko AI, Unger A, Reis MG. Slum health: diseases of neglected populations. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2007;7(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.United Nations. United Nations Sustainability and Development Goals: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/cities/. Published 2018. Accessed September 14, 2018.

- 5.United Nations Development Programme. UNDP Human Development Reports 2016. http://hdr.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/HTI. Published 2018. Accessed August 20, 2018.

- 6.World Bank. Population living in slums. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.POP.SLUM.UR.ZS?view=map. Published 2017. Accessed August 20, 2018.

- 7.United Nations Development Programme. Urban and Rural Population by Age and Sex, 1980–2015 (version 3, August 2014) http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/dataset/urban/urbanAndRuralPopulationByAgeAndSex.shtml. Published 2014. Accessed January 2, 2019.

- 8.D’Informatique IHDSE. Population Totale, De 18 Ans Et Plus Menages Et Densites Estimes en 2015. Port-au-Prince: IHSI;2015.

- 9.HaitiReport. Violence between gangs in Cite Soleil. http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/43a/512.html. Haiti Report. September 11 2002, 2002.

- 10.Guidi R. MINUSTAH focuses on security in Haiti's Cite Soleil slum. Americas quarterly web site. Published August 2009. Accessed August 21, 2018.

- 11.Doocy S, Cherewick M, Kirsch T. Mortality following the Haitian earthquake of 2010: a stratified cluster survey. Popul Health Metrics. 2013;11(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-11-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pape JW, Johnson WD, Jr, Fitzgerald DW. The earthquake in Haiti--dispatch from Port-au-Prince. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(7):575–577. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1001015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koenig SP, Rouzier V, Vilbrun SC, Morose W, Collins SE, Joseph P, Decome D, Ocheretina O, Galbaud S, Hashiguchi L, Pierrot J, Pape JW. Tuberculosis in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake in Haiti. Bull World Health Organ. 2015;93:498–502. doi: 10.2471/BLT.14.145649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. Haiti country profile: patterns of displacement. http://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/haiti. Published 2018. Accessed September 12, 2018.

- 15.Reif LK, Rivera V, Louis B, Bertrand R, Peck M, Anglade B, Seo G, Abrams EJ, Pape JW, Fitzgerald DW, McNairy ML. Community-based HIV and health testing for high-risk adolescents and youth. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2016;30(8):371–378. doi: 10.1089/apc.2016.0102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rivera V, Jean-Juste MA, Gluck S, et al. Diagnostic yield of active case finding for tuberculosis and HIV at the household level in slums in Haiti. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2017;21(11):1140–1146. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.17.0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rouzier V, Severe K, Juste MA, et al. Cholera vaccination in urban Haiti. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89(4):671–681. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.OpenStreetMap Foundation. www.openstreetmap.org. Published 2015. Accessed December 20, 2015.

- 19.ICF . Demographic and health survey interviewer’s manual. Rockville: ICF; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kessler RC, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Bromet E, Cuitan M, Furukawa TA, Gureje O, Hinkov H, Hu CY, Lara C, Lee S, Mneimneh Z, Myer L, Oakley-Browne M, Posada-Villa J, Sagar R, Viana MC, Zaslavsky AM. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population with the K6 screening scale: results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2010;19(Suppl 1):4–22. doi: 10.1002/mpr.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. WHO STEPS surveillance manual. Accessed from: http://www.who.int/chp/steps/manual/en/index3.html WHO. Published 2017. Accessed May 30, 2017.

- 22.Tymejczyk O, McNairy ML, Petion JS, et al. Hypertension prevalence and risk factors among residents of four slum communities: population-representative findings from Port-au-Prince, Haiti. J Hypertens 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT Jr, Roccella EJ, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. Global database on body mass index from: http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage=intro_3.html. Geneva: WHO;2016.

- 25.Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, Howes MJ, Normand SLT, Manderscheid RW, Walters EE, Zaslavsky AM. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184–189. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krieger N, Kosheleva A, Waterman PD, Chen JT, Koenen K. Racial discrimination, psychological distress, and self-rated health among US-born and foreign-born Black Americans. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(9):1704–1713. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Institut Haïtien de l’Enfance (IHE), ICF. Haïti. Enquête Mortalité, Morbidité et Utilisation des Services (EMMUS-VI) 2016–2017: Indicateurs Clés. Rockville, Maryland, and Pétion-Ville, Haïti2017.

- 28.National Cancer Institute Suveillance E, End Results (SEER) Program. Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program. Standard Populations - Single Ages. World (WHO 2000–2025) Standard. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/stdpopulations/stdpop.singleages.html. NCI. Published 2018. Accessed September 20, 2018.

- 29.Ali K. Among world’s most dense cities, Mumbai stands still at two. https://www.timesnownews.com/india/article/where-world-most-dense-populated-cities-mumbai/61774. TimesNowNews.com. May 26, 2017, 2017.

- 30.Desgroppes A, Taupin S. Kibera: The biggest slum in Africa? Les Cahiers de l'Afrique de l'Est. 2011;44:23–34. [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Population Review. Haiti population 2019. http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/haiti-population/. Published 2019.

- 32.Indian Census. Average size of slum households in India in 2001 and 2011. https://www.statista.com/statistics/619587/average-slum-household-size-india/. Published 2011. Accessed January 22, 2019.

- 33.Kyobutungi C, Ziraba AK, Ezeh A, Yé Y. The burden of disease profile of residents of Nairobi’s slums: results from a demographic surveillance system. Popul Health Metrics. 2008;6(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Institut Haïtien de l’Enfance (IHE) [Haïti], ICF. Enquête Mortalité, Morbidité et Utilisation des Services, Haïti, 2016–2017. Rockville, Maryland, and Pétionville, Haiti: IHE et ICF;2018.

- 35.Chant S, McIlwaine C. Cities, slums and gender in the global south: towards a feminised urban future. Routledge; 2015.

- 36.Pandey A, Sengupta B Socio-demographic profile of an urban slum of Kolkata, 2013: a Snapshot. Indian Journal of Hygiene and Public Health. 2015.

- 37.Montgomery MR, Stren R, Cohen B, Reed HE. Cities transformed: demographic change and its implications in the developing world. London, UK: Routledge; 2013.

- 38.Donato KM, Gabaccia D. Gender and international migration. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2015

- 39.Minnesota Population Center. Harmonized international census data for social science and health research: version 7.1. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMSInternational.Last date modified September 2018. https://international.ipums.org/international/. Accessed October 20, 2018

- 40.Horton R. The neglected epidemic of chronic disease. Lancet. 2005;366(9496):1514. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67454-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strong K, Mathers C, Leeder S, Beaglehole R. Preventing chronic diseases: how many lives can we save? Lancet. 2005;366(9496):1578–1582. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67341-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. GBD Compare Data Visualization. Available from: http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare. IHME, University of Washington. Published 2017. Accessed September 20, 2017.

- 43.Joshi MD, Ayah R, Njau EK, Wanjiru R, Kayima JK, Njeru EK, Mutai KK. Prevalence of hypertension and associated cardiovascular risk factors in an urban slum in Nairobi, Kenya: a population-based survey. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1177. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van de Vijver SJ, Oti SO, Agyemang C, Gomez GB, Kyobutungi C. Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension among slum dwellers in Nairobi, Kenya. J Hypertens. 2013;31(5):1018–1024. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835e3a56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heitzinger K, Montano SM, Hawes SE, Alarcon JO, Zunt JR. A community-based cluster randomized survey of noncommunicable disease and risk factors in a peri-urban shantytown in Lima, Peru. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2014;14:19. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-14-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Unger A, Felzemburgh RD, Snyder RE, et al. Hypertension in a Brazilian urban slum population. J Urban Health. 2015;92(3):446–459. doi: 10.1007/s11524-015-9956-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anand K, Shah B, Yadav K, et al. Are the urban poor vulnerable to non-communicable diseases? A survey of risk factors for non-communicable diseases in urban slums of Faridabad. Natl Med J India. 2007;20(3):115–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bunker SJ, Colquhoun DM, Esler MD, et al. “Stress” and coronary heart disease: psychosocial risk factors. Med J Aust. 2003;178(6):272–276. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Linden W. Review: depression, social isolation, and certain life events are associated with the development of coronary heart disease. ACP J Club. 2003;139(3):81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sirivarasai J, Kaojarern S, Chanprasertyothin S, et al. Environmental lead exposure, catalase gene, and markers of antioxidant and oxidative stress relation to hypertension: an analysis based on the EGAT study. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:856319. doi: 10.1155/2015/856319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yan LL, Liu K, Matthews KA, Daviglus ML, Ferguson TF, Kiefe CI. Psychosocial factors and risk of hypertension: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. JAMA. 2003;290(16):2138–2148. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.16.2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Den Hond E, Nawrot T, Staessen JA. The relationship between blood pressure and blood lead in NHANES III. National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey. J Hum Hypertens. 2002;16(8):563–568. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cenat JM, Derivois D. Assessment of prevalence and determinants of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression symptoms in adults survivors of earthquake in Haiti after 30 months. J Affect Disord. 2014;159:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cerda M, Paczkowski M, Galea S, Nemethy K, Pean C, Desvarieux M. Psychopathology in the aftermath of the Haiti earthquake: a population-based study of posttraumatic stress disorder and major depression. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30(5):413–424. doi: 10.1002/da.22007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wagenaar BH, Hagaman AK, Kaiser BN, McLean KE, Kohrt BA. Depression, suicidal ideation, and associated factors: a cross-sectional study in rural Haiti. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12(1):149. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bhardwaj U, Sharma V, George S, Khan A. Mental health risk assessment in a selected urban slum of Delhi—a survey report. J Nurs Sci Pract. 2019;2(1):116–122. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Greif MJ, FN-A D. How community physical, structural, and social stressors relate to mental health in the urban slums of Accra, Ghana. Health Place. 2015;33:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mumford DB, Minhas FA, Akhtar I, Akhter S, Mubbashar MH. Stress and psychiatric disorder in urban Rawalpindi: community survey. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177(6):557–562. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.6.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mullick MS, Goodman R. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among 5-10 year olds in rural, urban and slum areas in Bangladesh: an exploratory study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40(8):663–671. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0939-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aillon JL, Ndetei DM, Khasakhala L, Ngari WN, Achola HO, Akinyi S, Ribero S. Prevalence, types and comorbidity of mental disorders in a Kenyan primary health centre. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(8):1257–1268. doi: 10.1007/s00127-013-0755-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fleitlich B, Goodman R. Social factors associated with child mental health problems in Brazil: cross sectional survey. BMJ. 2001;323(7313):599–600. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7313.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gruebner O, Khan MM, Lautenbach S, et al. Mental health in the slums of Dhaka - a geoepidemiological study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:177. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]