Abstract

Excessive alcohol consumption has been shown to increase HIV risk for men who have sex with men (MSM) and compromise HIV prevention behaviors. However, there is limited contextual understanding of alcohol use for MSM in rural sub-Saharan African settings, which can inform and direct HIV interventions. Applying an adaptation of PhotoVoice, we worked with 35 HIV-positive MSM who created photo-essays about alcohol and HIV in Mpumalanga. A semi-structured protocol was used in focus group discussions that were audio-recorded, translated and transcribed. Transcript data and visual data of 24 photo-essays were analyzed using a constant comparison approach. We found that participants used alcohol to build and sustain social networks, meet sexual partners, and enhance sexual experience. Excessive alcohol use was common and increased HIV risk behaviors within a community of MSM who maintained multiple partnerships. Our study suggests that HIV interventions need to address excessive alcohol use to mitigate the associated HIV risk at both the individual and community levels.

INTRODUCTION

Excessive alcohol use by men who have sex with men (MSM) in rural and urban African settings has been associated with increased STI and HIV risk behaviors (Bryant, Nelson, Braithwaite, & Roach, 2010; Kim et al., 2016; Lane, Shade, McIntyre, & Morin, 2008; Pitpitan et al., 2013). Alcohol consumption that leads to increased risk of harm to one’s health defines excessive alcohol use (Organization, 2010). In South Africa, the limited alcohol research with MSM has demonstrated that there is excessive drinking behaviors, consuming more than six beverages per drinking episode at least twice a month, which is often associated with HIV risk behavior (Knox et al., 2017; Lane et al., 2011, 2014; Morojele et al., 2006; Nkosi, Rich, & Morojele, 2014). Further, sensation seeking and expectancies from alcohol use lowers an individual’s perceived risk for acquiring HIV and STI’s, and among MSM, this behavior coincides with increased frequency of unprotected anal sex (Heath, Lanoye, & Maisto, 2012; Lane et al., 2008; Lu et al., 2013; Maguina et al., 2013).

Further, HIV acquisition risk is high in drinking venues where there is excessive alcohol use, limited availability of biomedical prevention like condoms and lube, and transactional sex that hinders the ability of someone to negotiate HIV prevention (T. Lane, Mantell, J., Osmand, T., Sandfort, T., Dunkle, K., Kegeles, S., Struthers, H., McIntyre, J., June 2012; T. Lane, Osmand, T., Struthers, H., Dunkle, K., Mantell, J., Sandfort, T., Kegeles, S., McIntyre, J., June 2012; Osmand, June 2012) It is generally understood that excessive alcohol use coupled with limited HIV prevention have contributed to the high HIV prevalence for MSM in South Africa, with an HIV-positive range of 17–50.2% across most South Africa provinces including Mpumalanga where this study was conducted (Baral et al., 2011; Hugo et al., 2016; Lane et al., 2011; Rispel, Metcalf, Cloete, Reddy, & Lombard, 2011). However, the social context of alcohol use is not fully understood for MSM and what contributes to excessive alcohol use and the associated HIV risk in rural African settings like Mpumalanga.

Therefore, we conducted a participatory research study with Black, HIV-positive MSM who live in rural areas of Mpumalanga Province in order to understand the social context of alcohol use and its association with HIV risk behaviors.

METHODOLOGY

We adapted PhotoVoice to work with MSM living with HIV in Mpumalanga, a province on the Eastern side of South Africa. PhotoVoice is a participatory research methodology developed by Wang and Burris (1997), and has been utilized to examine the social determinants of health for marginalized groups within communities (Davtyan, Farmer, Brown, Sami, & Frederick, 2016; Teti, French, Bonney, & Lightfoot, 2015; C. Wang & Burris, 1997). We utilized PhotoVoice in order to solicit the context of alcohol use and HIV risk behaviors as well as how MSM perceive these are associated in their communities.

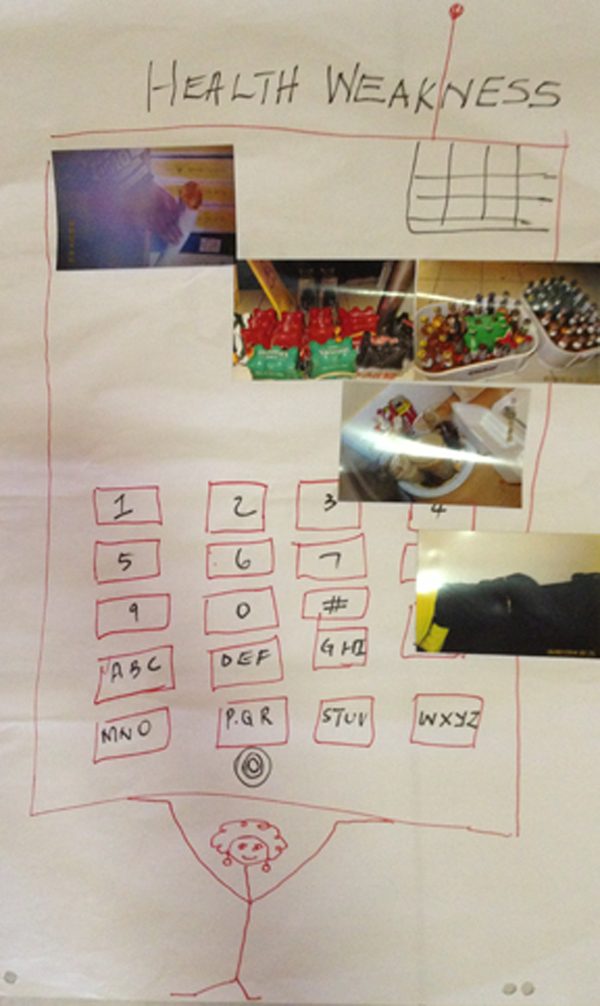

Our adaptation of PhotoVoice has been reported elsewhere, but we summarize our methods here as a series of three phases (Daniels et al., 2017). The first phase involved a reflection workshop where participants were placed into small groups in which they outlined their health needs and strengths while living with HIV. Each small group created a poster that showed what they felt were health needs and strengths, and they then presented their posters to the larger group for discussion (C. C. Wang, 1999). Also, during this first phase, participants received basic photography training, a digital camera and a journal wherein they kept a log of their photos including where and when the photo was taken and how the photo represented their health need. During the two-week second phase, participants took at least 10 photos that represented their health needs and strengths based on the reflection workshop coupled with log entries.

In the third phase, participants worked in assigned groups to present their individual printed photos to each other and then collectively created a photo-essay that captured a theme or themes that they identified as shared. Participants used at least one photo from each group member to communicate a theme or idea about living with HIV. They arranged the photos on a poster and were able to draw additional content to link the images together into their selected themes. After each group designed their photo-essay, then they presented their photo-essays to the larger group for discussion. The small and large group activities in Phases 1 and 3 took 90–150 minutes each.

Participant Recruitment.

We recruited HIV-positive, Black MSM living in rural and peri-urban areas of Mpumalanga, which included township and village settings. We used a snowball sampling method for this study since HIV-positive MSM had not been recruited for a study in this setting before this one. HIV-positive MSM are often linked to small social networks of HIV-positive and -negative MSM who know each other’s HIV status (Tucker, 2009). We approached three gate-keepers or leaders of social networks, and we explained the study and demographic profile of participants that was required. These gate-keepers were known leaders in the community who had participated in MSM-focused research in the past and not all were HIV-positive. Each gatekeeper was asked to recruit 10 participants who were HIV-positive, over 18 years of age, and Black MSM within their social networks.

Data analysis.

We conducted the study in English, IsiZulu and IsiSwati. The workshops and individual interviews were audio-recorded, translated and transcribed, and analyzed. We used a constant comparison approach where codes and themes were developed through an iterative process (Daniels et al., 2017; Mitchell et al., 2016). Two researchers coded the transcripts separately, and then met to discuss the coding in order to identify themes in the transcripts. Also, the researchers coded the photo-essays together using the same codes during these meetings. Findings from the transcripts and photo-essays were triangulated to: 1) assess consistency across data sources, 2) and then to identify major themes that develop from multiple discussions between researchers about data interpretation (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011). After completing our analysis, we identified representative quotes and archetype photo-essays that reflect the findings that we present here.

FINDINGS

A total of 35 participants were recruited into the study, and the participant age range was 18–40 years old with a median age of 24 years. As part of the reflection workshop, participants decided to take photos of experiences and decisions that they perceived led them to test HIV-positive. In all 24 photo-essays, there were images of alcohol use at taverns and house-parties. What emerged from these photo-essays was a single theme, a process of behaviors and decision-making where alcohol-use played a significant role in being social and maintaining HIV risk.

Nearly all participants described how alcohol was used to develop and sustain social relationships and to pursue sexual partners. One participant explained the use of alcohol in the MSM community: “Okay we drew a picture of a cell phone because we use social networks a lot for dagga [marijuana] and alcohol and parties. That’s why we represented it with a cell phone.” In Photo-Essay 1, a cell phone is drawn on the paper to represent a means to network with photos representing different aspects of socializing like using alcohol and marijuana and a bed representing sex. Participants stated that alcohol and marijuana helped them to socialize with other MSM in taverns and at house-parties, and they used cell phones to “grab a burger” (a sex hook-up). Alcohol was not perceived as negative for socializing, and participants described these activities as typical MSM social life that had benefits, and risks if they drank too much.

Specifically, not only did participants use alcohol to build confidence to talk about ideas with friends and pursue sexual partners, but they also used alcohol to get drunk because they believed it enhanced and extended sexual pleasure. Almost all the photo-essays had an image representing alcohol use linked to sex, and participants discussed the relationship between alcohol and their sex lives in Mpumalanga.

Participant 2: I was speaking with my other friend and we were drunk, alcohol is something that takes out fear from someone. Because if you are drunk you are not afraid of doing anything…You enjoy being with lovers, friends etc. and share ideas, you’re not afraid to communicate…It gives you power when in bed…

Researcher 1: Let’s see. When you’re drunk you can have more sex?

Participant 2: Yes. There are some beers that give you stamina, like stout….

Researcher 2: So how often do you use alcohol for sex?

Participant 3: I use it every weekend

Research 1: Every weekend?

Participant 2: Once a month

Research 1: If it’s once a month, when is it?

Participant 2: At the end of the month

Participants stated they used alcohol to get drunk so that they can have sex. Alcohol was present at social gatherings, and it was used to increase confidence and sexual stamina with multiple partners. For some participants, combining alcohol and sex occurred every weekend and for others this happened once a month usually corresponding with the distribution of paychecks and social service payments at month end. Getting drunk decreased the fear of any health or social repercussions from having sex.

This process of ‘drinking alcohol until drunk’ lowered inhibitions for sex, which led some participant to not use any prevention method. This process is reflected in Photo-Essay 2. In this essay, sale prices for alcohol are shown that will be bought to supply a house party that will lead to sex and then regret the next morning is represented by empty crumpled alcohol boxes. The last image is taken inside a clinic that some participants described as the outcome of unprotected sex. As one participant described as a common experience for MSM in taverns, “They don’t use condoms and are not circumcised…They [men] don’t do foreplay but offer drinks, then [you both] take a corner [in the tavern] and [they] have sex [anal sex] with you.” Further, in the large group discussions when asked by researchers, ‘how does booze influence your use of condoms’, participants frequently discussed regret about unprotected sex when they or others were drunk at house-parities or taverns:

Participant 13: “The drinking of the booze [alcohol], you see, after drinking when we’re with our friends, we were drinking this booze the same day. After drinking booze when we were drunk, we were going with our partners to the house doing things together, having sex, things that we won’t regret tomorrow. Ya. That’s the work of the booze. It makes us shameless of what we do when we were drunk.

Participant 12: Do you use a condom after you have sex on the grounds [at the house], do you use condoms?

Participant 13: Not most of the time because, me and my partner, we go together when checking on ourselves at the clinic [HIV testing]. Not most of the time but sometimes. We trust each other. Sometimes we think it’s wasting our time.”

Participants discussed how alcohol influences their HIV prevention decision-making. Most felt that alcohol led to them to not use condoms or be in situations where condoms seemed to be difficult to negotiate such as the quote above about unprotected sex in taverns. Further, some participants implied that alcohol can serve as an excuse to not have safe sex, that alcohol is to blame for not using condoms rather than themselves, which is shown in how they use the words ‘won’t regret’ and ‘shameless’ as the ‘work of the booze’. In many ways, some participants described alcohol as something that takes over your body and influences your decisions, like having unsafe sex, even though the repercussions could be HIV transmission and infection of their partner.

Also, some participants described having trust in their partner’s monogamous behavior in order to justify not using condoms, as in the participant statement above, which reflected a common couple who were sero-discordant. Participants stated that HIV testing was ‘wasting our time’ since they believed they were in a monogamous relationship, and they ‘trust[ed] each other’. Across the sites, participants discussed monogamy as a reason to not use condoms, yet in this context, multiple partnerships are common, as one participant explained, ‘All gays are lustful. Even though they are in a relationship, they still lust [have sex with] after other people’. Most MSM explained that they pursued and had relationships with boyfriends of their friends or other MSM in the community. Yet, even though they may not use condoms due to a perceived monogamy and trust, some participants did state that they tested for HIV with their partner, but we found that the attitudes and practices around HIV testing varied among the men in our sample. Further, HIV testing was never represented in association with being well and having sex; it was represented only in association with illness in all the photo-essays in this study (Daniels et al., 2017).

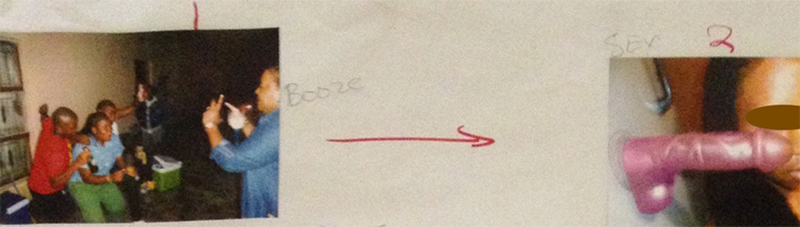

Photo essay 3 represents the process of getting drunk to enable unprotected sex, and the consequent increased risk of acquiring HIV. In this essay, a photo sequence is shown where drinking leads to sex. Here, in the first photo, a group of friends are drinking and partying, and the next photo shows a dildo and someone’s angry face to represent getting HIV infected from sex without a condom. The participant designed these photos to show how his experience of using alcohol excessively led to him getting drunk and having unprotected sex, which he believed led to him acquiring HIV. Further, many participants attributed their HIV-positive status to the process of drinking too much alcohol, getting drunk, and then having unprotected sex. As one participant explained: “Booze is the main factor that got me where I am today. Because back then, when I was drunk, I couldn’t protect myself and practice safe sex. I’m drunk and I’ll just get it done [have sex]. Remember there weren’t any of those [condoms] back then. So, looking back, I realize that if I had done things in a better way, I wouldn’t be here. But anyway, there’s nothing I can do. It is what it is.” This participant was not alone, many participants noted that alcohol enabled them to have quick sex and created a situation that limited their ability and desire to negotiate safer sex. They also noted that condoms were not readily available all the time. Participants regretted this practice and used phrases such as ‘If I had done things in a better way, I wouldn’t be here’, as the participant explains above.

DISCUSSION

This study created an opportunity for HIV-positive MSM to outline the contextual relationship between alcohol and HIV through PhotoVoice (Davtyan et al., 2016; Teti, Pichon, Kabel, Farnan, & Binson, 2013). We found that alcohol use had social and sexual benefits for MSM yet also contributed to increased HIV risk in this community.

First, alcohol use is a key aspect of MSM social lives, and is perceived to help MSM maintain their contact with and inclusion in supportive social networks. For many participants, alcohol was an important lubricant for socializing, a means to maintain social bonds within a small community of MSM living in a rural setting where the main venues for MSM community gatherings are MSM-friendly taverns and house parties (Daniels et al., 2017; Osmand, June 2012). Similar research has demonstrated that drinking and drinking venues for men serve as a means to build and maintain social support, or connectness, within communities (Velloza et al., 2017). We interpret this use of alcohol as largely positive since it formed part of the larger process of MSM community building and sustainability in settings where there may be few venues tailored to their social needs (Knox et al., 2016; Mantell, Tocco, Osmand, Sandfort, & Lane, 2016; Vagenas et al., 2017).

Second, alcohol was perceived as important and useful for sex in that it was used to enhance the experience. Alcohol consumption made sex exciting for most by building confidence to pursue sexual partners, creating sexual stamina, and enhancing sexual experience. In taverns and house-parties, MSM socialize and/or search for partners, and alcohol facilitates each endeavor. Increased evidence has shown that drug-use including alcohol consumption are commonly used to enhance sexual experience for MSM, and that goal of substance use does not increase HIV risk per se (Bourne & Weatherburn, 2017; Nguyen et al., 2016). Rather, it is the lack of HIV prevention behaviors and availability, like condoms/lube and PrEP, that increases this risk.

Third, alcohol use associated with poor decision making and regret in terms of HIV prevention behaviors. Although drinking was perceived as part of a positive social dynamic and represented in the photo-essays as such, some participants also captured excessive alcohol use as binge drinking and their regret of this behavior through the photo-essays. All participants were HIV-positive and most attributed their HIV status to getting drunk and having unprotected sex. Many of them captured their emotional experiences related to excessive alcohol use that led to unprotected sex and HIV. Participants described consuming large quantities of alcohol within a community where alcohol use is associated with sex, which, in turn, led them to not use condoms (Daniels et al., 2017; Kalichman et al., 2007; Kalichman, Simbayi, Vermaak, et al., 2008; Kalichman, Simbayi, Jooste, et al., 2008; Lane et al., 2008; Lu et al., 2013). Although condoms and lube were available in some drinking venues, this supply was irregular as described by participants. As a result, this made it even more difficult to negotiate safe sex while drunk, and some participants made a decision to just have sex without a condom ‘just to get it done’, or when they found themselves in a tavern with someone who wanted to have unprotected sex them and provided them with alcohol to do so. However, within this context of multiple sexual partnerships and unprotected sex, a few participants did state that they tested with their partners, but it was not clear how frequent this testing took place.

In sum, participants described using alcohol to socialize and for sexual pleasure. There is some indication that alcohol was used as a transaction to have unsafe sex in taverns, but more research is needed here. We found that excessive alcohol use led to unsafe sex, and MSM blamed alcohol for their HIV-positive status.

LIMITATIONS

The results of this study do not represent all MSM in this setting. Also, our adaptation of the PhotoVoice method involved the development of group photo-essays that may have limited individual perspective, but we believe that this group process outlined shared understandings of alcohol use and HIV risk for MSM in this community. Finally, participants discussed alcohol use and HIV risk in taverns and house-parties, but we did not distinguish between these two settings and more research is needed to outline any differential alcohol-associated risk.

CONCLUSION

Getting drunk and not using condoms with partners is common practice, which is most likely contributing to the high HIV incidence rate in this setting. More HIV prevention research and programs are needed for MSM in this setting. Significant progress has been made in HIV prevention for MSM in Mpumalanga, but excessive alcohol use needs to be addressed to mitigate the associated HIV risk.

Photo Essay 1

Photo Essay 2

Photo Essay 3

REFERENCES

- Braithwaite RS, Nucifora KA, Kessler J, Toohey C, Mentor SM, Uhler LM, … Bryant K (2014). Impact of Interventions Targeting Unhealthy Alcohol Use in Kenya on HIV Transmission and AIDS-Related Deaths. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. doi: 10.1111/acer.12332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant KJ, Nelson S, Braithwaite RS, & Roach D (2010). Integrating HIV/AIDS and Alcohol Research. Alcohol Res Health, 33(3), 167–178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casale M (2015). The importance of family and community support for the health of HIV-affected populations in Southern Africa: what do we know and where to from here? Br J Health Psychol, 20(1), 21–35. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark JL, Konda KA, Silva-Santisteban A, Peinado J, Lama JR, Kusunoki L, … Sanchez J (2013). Sampling Methodologies for Epidemiologic Surveillance of Men Who Have Sex with Men and Transgender Women in Latin America: An Empiric Comparison of Convenience Sampling, Time Space Sampling, and Respondent Driven Sampling. AIDS Behav. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0680-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordova D, Parra-Cardona JR, Blow A, Johnson DJ, Prado G, & Fitzgerald HE (2015). ‘They don’t look at what affects us’: the role of ecodevelopmental factors on alcohol and drug use among Latinos with physical disabilities. Ethn Health, 20(1), 66–86. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2014.890173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels J, Maleke K, Lane T, Struthers H, McIntyre J, Kegeles S, … Coates T (2017). Learning to Live With HIV in the Rural Townships: A Photovoice Study of Men Who Have Sex With Men Living With HIV in Mpumalanga, South Africa. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2017.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davtyan M, Farmer S, Brown B, Sami M, & Frederick T (2016). Women of Color Reflect on HIV-Related Stigma through PhotoVoice. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care, 27(4), 404–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2016.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton LA, Kalichman SC, Pitpitan EV, Cain DN, Watt MH, Sikkema KJ, … Pieterse D (2013). The relationship between attending alcohol serving venues nearby versus distant to one’s residence and sexual risk taking in a South African township. J Behav Med. doi: 10.1007/s10865-013-9495-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath J, Lanoye A, & Maisto SA (2012). The role of alcohol and substance use in risky sexual behavior among older men who have sex with men: a review and critique of the current literature. AIDS Behav, 16(3), 578–589. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9921-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heestermans T, Browne JL, Aitken SC, Vervoort SC, & Klipstein-Grobusch K (2016). Determinants of adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive adults in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health, 1(4), e000125. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess KL, Chavez PR, Kanny D, DiNenno E, Lansky A, Paz-Bailey G, & Group, Nhbs Study. (2015). Binge drinking and risky sexual behavior among HIV-negative and unknown HIV status men who have sex with men, 20 US cities. Drug Alcohol Depend, 147, 46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imrie J, Hoddinott G, Fuller S, Oliver S, & Newell ML (2013). Why MSM in rural South African communities should be an HIV prevention research priority. AIDS Behav, 17 Suppl 1, S70–76. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0356-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Cain D, & Jooste S (2007). Alcohol expectancies and risky drinking among men and women at high-risk for HIV infection in Cape Town South Africa. Addict Behav, 32(10), 2304–2310. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Vermaak R, Jooste S, & Cain D (2008). HIV/AIDS risks among men and women who drink at informal alcohol serving establishments (Shebeens) in Cape Town, South Africa. Prev Sci, 9(1), 55–62. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0085-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi L, Jooste S, Vermaak R, & Cain D (2008). Sensation seeking and alcohol use predict HIV transmission risks: prospective study of sexually transmitted infection clinic patients, Cape Town, South Africa. Addict Behav, 33(12), 1630–1633. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.07.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EJ, Hladik W, Barker J, Lubwama G, Sendagala S, Ssenkusu JM, … Crane Survey, Group. (2016). Sexually transmitted infections associated with alcohol use and HIV infection among men who have sex with men in Kampala, Uganda. Sex Transm Infect, 92(3), 240–245. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2015-052034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox J, Reddy V, Lane T, Hasin D, & Sandfort T (2016). Substance Use and Sexual Risk Behavior Among Black South African Men Who Have Sex With Men: The Moderating Effects of Reasons for Drinking and Safer Sex Intentions. AIDS Behav. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1652-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane T, Mantell J, Osmand T, Sandfort T, Dunkle K, Kegeles S, Struthers H, McIntyre J. (June 2012). Switching on “After Nine”: The Duality of Sexual Identity and Partnerships among Black MSM in Rural South African Towns. Paper presented at the International AIDS Society Meeting. [Google Scholar]

- Lane T, Osmand T, Marr A, Shade SB, Dunkle K, Sandfort T, … McIntyre JA (2014). The Mpumalanga Men’s Study (MPMS): Results of a Baseline Biological and Behavioral HIV Surveillance Survey in Two MSM Communities in South Africa. PLoS One, 9(11), e111063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane T, Osmand T, Marr A, Struthers H, McIntyre JA, & Shade SB (2016). Brief Report: High HIV Incidence in a South African Community of Men Who Have Sex With Men: Results From the Mpumalanga Men’s Study, 2012–2015. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 73(5), 609–611. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane T, Osmand T, Struthers H, Dunkle K, Mantell J, Sandfort T, Kegeles S, McIntyre J. (June 2012). Health Empowerment: Using Targeted Ethnography to Adapt the Mpowerment Intervention for South African MSM. Paper presented at the International AIDS Society Meeting. [Google Scholar]

- Lane T, Raymond HF, Dladla S, Rasethe J, Struthers H, McFarland W, & McIntyre J (2011). High HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in Soweto, South Africa: results from the Soweto Men’s Study. AIDS Behav, 15(3), 626–634. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9598-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane T, Shade SB, McIntyre J, & Morin SF (2008). Alcohol and sexual risk behavior among men who have sex with men in South african township communities. AIDS Behav, 12(4 Suppl), S78–85. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9389-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Han Y, He X, Sun Y, Li G, Li X, … Raymond HF (2013). Alcohol use and HIV risk taking among Chinese MSM in Beijing. Drug Alcohol Depend, 133(2), 317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguina JL, Konda KA, Leon SR, Lescano AG, Clark JL, Hall ER, … Group, Nimh Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial. (2013). Relationship between alcohol consumption prior to sex, unprotected sex and prevalence of STI/HIV among socially marginalized men in three coastal cities of Peru. AIDS Behav, 17(5), 1724–1733. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0310-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantell JE, Tocco JU, Osmand T, Sandfort T, & Lane T (2016). Switching on After Nine: Black gay-identified men’s perceptions of sexual identities and partnerships in South African towns. Glob Public Health, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2016.1142592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JW, Torres MB, Joe J, Danh T, Gass B, & Horvath KJ (2016). Formative Work to Develop a Tailored HIV Testing Smartphone App for Diverse, At-Risk, HIV-Negative Men Who Have Sex With Men: A Focus Group Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth, 4(4), e128. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.6178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mmari K, Blum R, Sonenstein F, Marshall B, Brahmbhatt H, Venables E, … Sangowawa A (2014). Adolescents’ perceptions of health from disadvantaged urban communities: findings from the WAVE study. Soc Sci Med, 104, 124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organization, World Health. (2010). Global Strategy to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- Osmand T, Sandfort T, Mantell J, Dunkle K, Kegeles S, Struthers H McIntyre J, Lane T (June 2012). “One day we will come together and unite”: Imagining Community among MSM in Mpumalanga, South Africa. Paper presented at the International AIDS Society Meeting. [Google Scholar]

- Pitpitan EV, Kalichman SC, Eaton LA, Watt MH, Sikkema KJ, Skinner D, … Cain D (2013). Men (and Women) as “Sellers” of Sex in Alcohol-Serving Venues in Cape Town, South Africa. Prev Sci. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0381-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler GR, Lee HC, Lim RS, & Fullerton J (2010). Recruitment of hard-to-reach population subgroups via adaptations of the snowball sampling strategy. Nurs Health Sci, 12(3), 369–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2010.00541.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teti M, French B, Bonney L, & Lightfoot M (2015). “I Created Something New with Something that Had Died”: Photo-Narratives of Positive Transformation Among Women with HIV. AIDS Behav. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1000-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teti M, Pichon L, Kabel A, Farnan R, & Binson D (2013). Taking pictures to take control: Photovoice as a tool to facilitate empowerment among poor and racial/ethnic minority women with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care, 24(6), 539–553. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2013.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin K, Davey-Rothwell M, Yang C, Siconolfi D, & Latkin C (2014). An examination of associations between social norms and risky alcohol use among African American men who have sex with men. Drug Alcohol Depend, 134, 218–221. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagenas P, Brown SE, Clark JL, Konda KA, Lama JR, Sanchez J, … Altice FL (2017). A Qualitative Assessment of Alcohol Consumption and Sexual Risk Behaviors Among Men Who Have Sex With Men and Transgender Women in Peru. Subst Use Misuse, 52(7), 831–839. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2016.1264968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, & Burris MA (1997). Photovoice: concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ Behav, 24(3), 369–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CC (1999). Photovoice: a participatory action research strategy applied to women’s health. J Womens Health, 8(2), 185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]