Abstract

The human papillomavirus (HPV) causes several cancers and genital warts among sexually active adolescent and young adult (AYA) males. Quadrivalent HPV vaccines were approved for use in the AYA male population in 2010, but vaccination rates have plateaued at around 10%–15%. A better understanding of the barriers AYA male patients, their parents, and their health care providers (HCPs) experience with respect to vaccination uptake is necessary for tailoring interventions for this population. A literature search was conducted through the PubMed and PsycINFO databases in October 2017. Studies were included if they specified at least one barrier to vaccination uptake in AYA males. Studies were excluded if they did not focus on AYA males, their parents, or their HCP; were conducted outside the United States; or were published before 2010. A total of 23 studies were reviewed, and analysis found that these three groups (i.e., AYA males, parents, and HCPs) had significantly different concerns regarding vaccination. The identified themes included the lack of HPV vaccine awareness/information, misinformation about HPV, lack of communication, financial issues relating to uptake, demographic/perceived social norms, and sexual activity. Health care professionals working directly with AYA males and their parents should provide an open route of communication regarding these sensitive issues, and further educate families on the importance of HPV vaccines in reducing the incidence of certain cancers among men in later adulthood.

Keywords: HPV, HPV vaccination, oropharyngeal cancer, vaccination, prevention

Introduction

The human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the United States (US), accounting for 49.5% of STIs in adolescent and young adult (AYA) males 15–28 years of age.1 More than 16,500 HPV-associated cancers are diagnosed among males each year,2 and HPV is responsible for more than 60% of penile cancer and 90% of anal cancer cases in males in the US.2 Males are three times more likely to be infected with HPV than females, but future cancer incidence remains higher in females overall.2 HPV tends to present with few visible symptoms in men,2–4 making transmission and acquisition of HPV more prevalent among this population.2,5

The most popular vaccination against HPV will aid in preventing the transmission and acquisition of HPV for AYA males and their future partners, protecting them from future HPV-related health complications, including specific cancers and genital warts.2,6

The most popular vaccine for HPV, Gardasil©, was recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) for males 9–21 years of age in 2010. Following the ACIP recommendation, the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) chose to implement the following recommendation for adolescent males and the HPV vaccine: male adolescents should receive the first HPV vaccine between 11 and 12 years of age and complete the two-dose regimen before the age of 132; for adolescent males, who do not receive the first of the HPV series by 15, the CDC recommends the three-dose series.2 For specific male populations (e.g., men who have sex with men, gay or bisexual men), the HPV vaccine is recommended up to 26 years of age.2 For males who are not within special populations, the vaccine is permissive between 22 and 26 years of age.2

Despite the FDA's recommendation of the vaccine and the elevated level of risk for HPV infection among AYA males, vaccination rates remain low in this population.3 Vaccination completion rates in AYA males in 2016 ranged from 10.7% to 20.8%.3 HCPs recognize the importance of HPV vaccination among adolescent boys,2 but face difficulty in recommending HPV vaccination to their male patients due to the general population's lack of knowledge about HPV vaccination among this population.6 Other barriers to HPV vaccination in this population include insurance and cost issues, concerns about vaccine safety, misconceptions about personal relevancy of the vaccine and HPV risk, and other factors such as sexual activity, age, and number of sexual partners.7–12

The aim of this literature review was to identify barriers to HPV vaccination uptake within the US from the perspective of AYA males, their parents/caregivers, and their HCPs.

Materials and Methods

Data sources and study selection

The PubMed and PsycINFO databases were searched and cross-referenced with the following search terms on October 9, 2017: HPV, human papillomavirus, adolescent, teenager, teen, young adult, males, boys, men, cancer, Gardasil, prevention, vaccine, and vaccination. With the help of a research librarian, search terms were inputted into each database and results were saved for review of study inclusion/exclusion.

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria: (1) examined male adolescents/young adults (AYA males were identified as being between 15 and 29 years of age), (2) reported male adolescents/young adults', their parents', and/or their providers' perceptions of barriers to the HPV vaccine and/or HPV risk, (3) were published between February 2010, when the U.S. Federal Drug Administration (FDA) approved Gardasil for AYA males, and October 2017, and (4) were conducted within the US. Studies that did not allow for examination of male-specific results, separate from female results, and studies not written in or translated into English were excluded from the review.

Data extraction and analysis

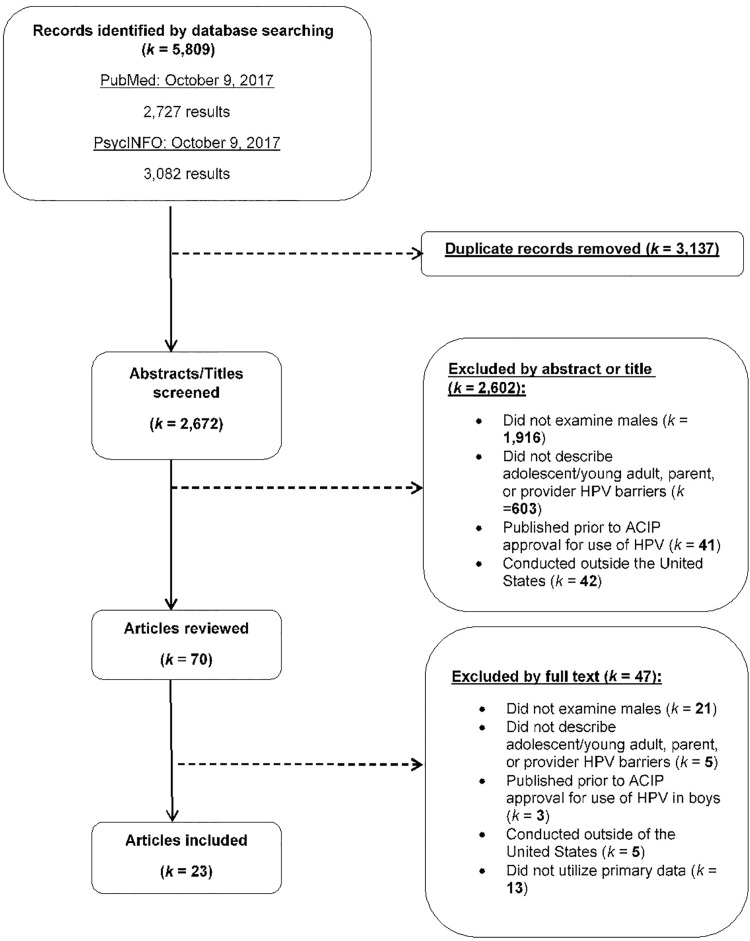

Our search yielded a total of 2672 unique articles. One reviewer (K.D.) reviewed article titles, and 1916 articles were eliminated because they did not examine males and 41 articles were published before 2010. Two reviewers (K.D. and J.M.) analyzed the remaining 715 abstracts. A total of 603 articles were eliminated because they did not describe AYA male, parent, or provider vaccination barriers, and 42 were eliminated because the studies were conducted outside the US (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Elimination process for this review. The PRISMA diagram details our search and selection process applied during this systematic literature review.

Two reviewers (Kate Dibble and Morica Hutchison) examined the remaining 70 full-text articles, eliminating 21 articles because they did not examine males; five because they did not describe AYA male, parent/caregiver, or provider vaccination uptake barriers; three because they were published before FDA recommendation for use of the HPV vaccine in boys; five because the studies were conducted outside the US; and 13 because they examined nonoriginal research (e.g., editorials and commentaries). A total of 23 articles were included in the literature review. We calculated Cohen's kappa statistic to assess interrater reliability (e.g., agreement) between reviewers on the inclusion and exclusion of articles, finding strong agreement (Cohen's kappa = 0.87).

To further code the data, an Excel spreadsheet was used to extract and categorize information about the study's authors, title, study design (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods), data collection methodology, study setting, and geographic location. Participant viewpoint (AYA male, provider, and/or parent), participant characteristics (adolescent male/young adult age, race/ethnicity of sample), proportion of previous HPV vaccination uptake, and reported barriers to uptake were also extracted. Information for each article can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Male Adolescent HPV Vaccination Uptake Included in Current Literature Review

| Quality | Author(s) | Study design | Study setting | Participants | Previous vaccination uptake | Barriers reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | Calo et al.20 Parents' willingness to get HPV vaccination for their adolescent children at a pharmacy |

Quantitative National web-based survey |

Recruited from a random national panel of US adults using random digit dialing, address based, or email with age-eligible male adolescents (11–17-year old) | 672 parents of 11–17-year-old male adolescents Parents were members of a standing, national panel of US adults maintained by survey research company 52% female 71% White, 13% Hispanic, 9% non-Hispanic Black 38% high school degree or less, 62% some college or more |

64% no vaccine at beginning of study 24% no vaccine at conclusion 36% received one or two doses |

Only 29% would get sons vaccinated at pharmacies 55% did not receive physician recommendation 34% thought the HPV vaccine as more important, 25% thought of it as less important 18% believes that sons as young as 11 could get HPV vaccine 70% were unaware that males as young as 11 could receive the vaccine 37% said they would like to find out about pharmacy vaccinations through physician |

| 24 | Farias et al.30 Association of physicians perceived barriers with HPV vaccination initiation |

Quantitative (web-based survey and electronic medical records) Pediatricians' perceived barriers to vaccinating adolescents 11–18 years of age |

Recruited providers from the Texas Children's Pediatrics—a large network of clinics in Houston, TX Compared to medical records (electronic) of HPV vaccination initiation over 12 months |

134 providers (36.6% under 40, 29.6% 40–49, 17.2% 50–59, and 16.4% over 60) Most were White (50%), Black (9%), or Hispanic (9.7%) 70.2% female, 29.9% male |

18.6% reported initiating the vaccine regimen among 36,827 patients | 18.7% reported barriers concerning level of knowledge about HPV 25.4% had concerns about parents' negative reaction about the HPV vaccine 73.1% reported discomfort talking about STIs with parents/patients 25.4% reported concern of financial burden on patients 15.7% concerned about vaccine safety 10.5% concerned about vaccine efficacy 70.9% not required for school attendance 64.2% concerned with the time it takes to discuss HPV vaccine 73.1% difficulty ensuring three-dose regimen among patients 82.8% infrequent office visits by patients |

| 24 | Greenfield et al.33 Strategies for increasing adolescent immunizations in diverse and ethnic communities |

Mixed methods (in-person surveys and three focus groups) Conducted with mothers of 11–18-year-old males who were Hispanic, Ethiopian, and/or Somali from King County, Washington |

Three school systems of Burien, SeaTac, and Tukwila (the top three most diverse cities in Washington) | 157 parents (mean age 41) and 45 adolescent males (mean age 15) Parents were 35% Somali, 33% Hispanic, and 32% Ethiopian; 99% foreign born Adolescents were 38% Somali, 27% Hispanic, and 36% Ethiopian; 60% foreign born |

Reported by parent: 0% of Somali sons 40% of Hispanic sons 16% of Ethiopian sons Reported by sons: 0% of Somali sons 30% of Hispanic sons 20% of Ethiopian sons |

Surveys: 38% of parents heard of HPV in males Parents reported their main reason for not vaccinating was not knowing that vaccines were recommended 22% of sons heard of HPV 25% of sons had heard of the HPV vaccine Focus groups: Parents did not trust recommendations from pharmacists or school nurses—lack of trust Nearly universal to vaccinate if recommended to do so by physician Existing misconceptions regarding the HPV vaccine, severity of HPV, complications, and how it is transmitted Parents expressed a desire to access vaccine information in their native language |

| 24 | Griebeler et al.28 Parental beliefs and knowledge about male HPV vaccination in the US: A survey of a pediatric clinic population |

Quantitative (in-person surveys) | Convenience sample of a low-income, Medicaid pediatric clinic in the US | 102 parents of male adolescents 9–20 years of age Pediatric clinic demographics: 75% utilized Medicaid 85% White and 10% Black No participant demographics were collected for anonymity purposes |

66% of parents with sons younger than 12 have been vaccinated | Majority of parents reported some knowledge of HPV (50%) or nothing (38%), followed by a lot (11%) 13% thought male HPV is not serious 8% thought that vaccines are against personal beliefs 38% were concerned of vaccine safety (new vaccine) Child does not want to be vaccinated (4%) Child is too young (38%) Only 14% answered all knowledge questions correctly 30% were unable to identify any health outcomes of HPV in males Of those that didn't vaccinate: 54% fulfilled child's wish to not be vaccinated; 38% reported child was too young/feared that vaccine would negatively affect child behavior |

| 24 | Reiter et al.17 Default policies and parents' consent for school-located HPV vaccination |

Quantitative (experimental, 3 × 2 between-subjects factorial design) |

Recruited parents through an existing online, national survey of US HIS households Only looked at parental response in this article |

Parents: 404 parents of males 11–17 years of age 61% younger than 45 years, 67% were non-Hispanic White, 14% Black, 15% Hispanic, and 82% lived in an urban area Sons: 404 sons—28% 11–12 years, 37% 13–15 years, and 35% 16–17 years 63% White, 12% Black, and 15% Hispanic |

0% of sons | Parents: 29.9% more likely to opt in if vaccinated at school 62% of the control group did not differ from opt in or out 70% did not know whether they will vaccinate their sons in the next year More likely to vaccinate if vaccinated with other vaccines rather than by itself |

| 23 | Tan and Gerbie27 Perception, awareness, and acceptance of HPV disease and vaccine among parents of boys 9–18 years of age |

Quantitative (in-person paper survey—given in both English and Spanish) | Recruited parents of boys 9–18 years of age, who obtained primary care from pediatrician or public health clinics in Chicago, IL, from 2011 to 2013 | 516 parents (mean age of 41.5) of males 9–18 years of age PCP Parents: 77.39% White, 9.57% Black, 4.4% Hispanic, and 4.7% Asian 97.3% private health insurance Public health parents: 5.59% White, 25.52% Black, 62.24% Hispanic, and 4.55% Asian 92.31% Medicaid |

0% of sons 44.35% of the PCP parental group would vaccinate, but 94.55% said that they would only if a physician recommended it |

PCP parental group: 91.74% had heard of HPV and 86.96% heard of the vaccine 44.35% knew about the HPV vaccine for males 39.13% responded “Don't know” when asked what diseases HPV caused, but 36.52% knew that it caused genital warts 53.91% knew it was a common infection, and was sexually transmitted (76.52%) Few knew that it caused cancer in males (16.96%) Public health parental group: 65.93% have heard of HPV and 55.24% heard of the vaccine 26.92% knew about the HPV vaccine for males 68.53% did not know what HPV caused, but 16.43% knew it caused genital warts 33.33% knew it was a common infection, and 50.35% knew it was sexually transmitted 18.82% knew it caused cancer in males |

| 23 | Schuler and Coyne-Beasley43 Has their son been vaccinated? Beliefs about other parents matter for HPV vaccine |

Quantitative (cross-sectional, in-person, self-administered survey) | Pediatric clinic that provides pediatric and subspecialty care in North Carolina | 267 parents of sons 9–21 years of age 48% younger than 40 21% male, 79% female 51% White, 40% Black, and 9% other 94% non-Hispanic 55% married 19% had sons 9–10 years, 18% 11–12 years, and 63% 13–21 years |

0% of sons 63% of parents were probably going to vaccinate within the next year 8% would definitely not vaccinate |

15–18% of parents had correct answers regarding anal, penile, and oropharyngeal cancers caused by HPV 29% of parents would not vaccinate their sons in the next year Parents who had others in their community vaccinating their sons the same age were 4 × more likely to vaccinate sons in the next year 59% of parents were worried HPV vaccines cause unknown, long-term side effects |

| 23 | Schuler, DeSousa, and Coyne-Beasley40 Parents' decisions about HPV vaccine for sons: The importance of protecting sons' future female partners |

Quantitative (cross-sectional, in-person, self-administered survey) about sons | Pediatric clinic that provides pediatric and subspecialty care serving those 21 years and younger in North Carolina | 246 parents of sons 9–21 years of age 51% younger than 40 21% male, 79% female 52% White, 40% Black, and 8% other 57% married 21% 9–10 years, 20% 11–12 years, and 59% 13–21 years |

0% of sons | 76% would vaccinate sons to protect future female partners, and those who were not concerned about this were less likely to vaccinate 15% said they would vaccinate in the next year, 30% said that they would probably not vaccinate, and 8% said they would definitely not vaccinate Parents 40 years of age and older (83%) indicated that female partner protection would likely influence vaccine decisions compared to younger parents (70%) |

| 23 | Cates et al.21 Designing messages to motivate parents to get their preteenage sons vaccinated against HPV |

Mixed methods Five focus groups and interviews from 2009 to 2010 |

Focus groups: Recruited from churches and a middle school in rural Sampson county, North Carolina, through flyers and announcements Interviews: Completed at pediatric and adolescent health clinic affiliated with UNC Chapel Hill, recruited parents from university-based health clinics |

Focus groups: 29 parents of 11–12-year-old boys; 76% female, 67% older than 40, 100% Black Interviews: 100 parents of 9–13-year-old boys; 77% female, 46% Black, 44% White, and 10% other; 69% mothers, 19% fathers, and 12% other relatives |

Interview: 6% of sons had received first dose 16% said they would “definitely” or “probably” get sons vaccinated within 12 months |

Focus groups: Low awareness of HPV (unaware of serious consequences for males or that males could get HPV) Low awareness of the HPV vaccine Perceived susceptibility/severity of HPV in males (thought son at risk if they were sexually active) Three-dose series cost too much Vaccine side effects Long-term safety and effectiveness Feeling like “guinea pigs,” compared the HPV vaccine to the syphilis study in the past Interviews: 11% heard about the HPV vaccine for males 48% reported concerns for vaccine safety and side effects 25% were unaware of the male prevalence of HPV 19% were distracted by number of doses needed |

| 23 | Oldach and Katz42 Ohio Appalachia public health department personnel: HPV vaccine availability, and acceptance and concerns among parents of male and female adolescents |

Qualitative (semistructured telephone/questionnaire interviews) | Health departments in Appalachian Ohio identified through the Ohio Department of Health (ODH) website Member of research teams called each health department to schedule telephone interview |

46 public health departments and lead providers in those departments (32 county level, 14 city level) 24 public health nurses, 21 directors of public health nursing, and 1 public health supervisor Race/ethnicity was not reported |

N/A | Provider barriers: 55.6% lack of knowledge about HPV in males 37.8% concern about vaccine side effects 35.6% new vaccine concerns 35.6% patients are not sexually active or too young 22.2% negative publicity form media or community 15.6% vaccine causes sexual promiscuity 15.6% vaccine not mandatory 13.3% difficulty discussing HPV vaccine 8.9% vaccine series completion rate 6.7% patient does n0t like vaccines (e.g., pain) 4.4% no vaccination because of religious beliefs Provider-reported parental barriers: 44.4% unaware of vaccine for males 13.3% knew more information about the HPV vaccine and females 35.6% had lack of knowledge of why males should receive the HPV vaccine 11.1% of parents perceived HPV as less severe as other STIs |

| 22 | Thompson et al.35 HPV vaccination: What are the reasons for nonvaccination among US adolescents? |

Mixed methods (parent telephone interview, and then provider survey to verify vaccination status) | Recruited from NIS-teen survey from 2010 to 2012 and contacted a second time for interview | 59,897 parents of male adolescents from 2010 to 2014 58.8% of parents had adolescent sons 68% were female, 25.6% male, 3.0% grandparents Race/ethnicity was not reported |

0% overall vaccination uptake 51.9% reported not getting their son vaccinated 31.6% were unlikely to receive the vaccine |

Most parents who did not vaccinate sons (or said that they would not) did so because they believed that the HPV vaccine is not needed for males Among those who chose not to be vaccinated, lack of knowledge was a major factor Sons are not sexually active Vaccine was not recommended Safety and side effects caused by the HPV vaccine were a concern |

| 22 | Luque et al.32 Recommendations and administration of the HPV vaccine to 11- to 12-year-old girls and boys: A statewide survey of Georgia vaccines for children provider practices |

Quantitative cross-sectional (web-based, paper, and telephone self-administered survey) |

Recruited providers from 206 locations in GA through the GA vaccines for children provider list from 2010 to 2011 Probability 1-stage cluster sampling with counties as clusters |

217 providers (mean age of 51 years) 59% were White, 20% Black, 14% Asian And 94% non-Hispanic 57% male Mean number of years since residency training was 18 years |

N/A | 12% vaccine safety and efficacy 17% new vaccine with limited track record 15% adding another vaccine to schedule 12% lack of information about the vaccine 69% upfront cost of purchasing vaccine was high 73% cost of stocking vaccine 68% lack of reimbursement for vaccine from insurance 63% failure of insurance coverage in males 15% lack of time to discuss vaccine with patients 51% difficulty ensuring the three-dose regimen 23% vaccine not required for school 20% of providers would always recommend male patients get vaccinated |

| 21 | Reiter et al.23 Early adoption of the HPV vaccine among Hispanic adolescent males in the US |

Quantitative (secondary analysis of national, telephone survey) | Recruited parents through an existing online, NIS-teen from 2010 to 2012 | Parents: 4238 parents of adolescent sons (13–17 years old) Majority of mothers were at least 35 years (86%) and did not have college degrees (81.6%) Sons: 100% of sons were Hispanic; 86.1% of sons were Hispanic-White, 5.6% Black, and 8.3% other mixed Most sons were 13–15 years of age (62.4%) |

Initiation: 17.1% received at least one dose Initiation increased each year to 2.8% in 2010, 14.9% in 2011, and 31.7% in 2012 Overall: 5.5% of adolescent Hispanic males completed all three doses |

Parents: 23.6% reported lack of knowledge about HPV 40.2% was not sure about vaccination over the next year or not likely at all 22.5% believed vaccine is not needed 22% did not have provider recommendation Spanish-speaking parents were more likely to indicate lack of knowledge (19.9% vs. 32.9%) and not receiving a provider recommendation (17.7% vs. 32.2%) than English-speaking patients English-speaking parents were more likely to indicate believing vaccinations as not needed (27.2% vs. 10.6%), that their son was not sexually active (11.2% vs. 3.5%), that their child is male, therefore did not need the vaccine (7.5% vs. 2.2%), and being concerned about vaccine safety and side effects (6.8% vs. 3.1%) |

| 21 | Reiter et al.17,36 Improving HPV vaccine delivery: A national study of parents and their adolescent sons |

Quantitative (cross-sectional, web-based, self-administered survey) Dual-approach (list-assisted random-digit dialing and address-based sampling) |

Recruited parents through an existing online, national survey of US households | Parents: 506 parents—54% female, most 45 years of age or younger (61%) Majority non-Hispanic White (67%), Black (12%), and Hispanic (15%); with some college or more (56%) Sons: 391 sons—30% 11–12 years, 38% 13–15 years, or 31% 16–17 years Majority non-Hispanic White (61%), Black (12%), or Hispanic (16%) 79% saw physician within past year |

0% | Parents Preferred for child be vaccinated at doctor's office Preferred brief nurse visits for vaccination (65%) rather than pharmacy vaccination 29% believed insurance would not cover vaccination at school Sons Preferred to be vaccinated at doctor's office for initial vaccine; and a brief nurse visits for vaccination for two last shots 32% were embarrassed to be vaccinated |

| 21 | Reiter et al.16 HPV vaccine and adolescent males |

Quantitative (web-based, self-administered survey) | Recruited parents of adolescent sons 11–17 years of age (and later sons) from an existing national panel of US households | Parents: 547 participants (61% younger than 45) 67% White, 13% Black, 15% Hispanic, and 5% other; majority were married (82%) Sons: 421 participants (30% 11–12 years, 38% 13–15 years, and 32% 16–17 years) 61% White, 12% Black, and 16% Hispanic |

2% of sons received any HPV vaccine dosage <1% received all three doses |

Parents: 0.48% talked to sons about vaccine 21% sons' insurance covers vaccine 0.75% worry about sons getting HPV 0.93% perceive effectiveness of vaccine 0.67% perceived uncertainty about vaccine 0.53% perceived harms of HPV vaccine 80% were unaware that the HPV vaccine can be given to males 43% would give vaccine to son if it was free Sons: 75% had never heard of HPV 0.67% perceived themselves getting HPV 0.41% amount talking with parents about vaccine 0.60% reported peer acceptance of vaccine 1.06% anticipated embarrassment of getting HPV vaccine Sons willingness to get vaccinated was positively correlated to parent's willingness to get them a free HPV vaccine Reported high anticipated regret if they did not vaccinate and later got HPV or genital warts |

| 20 | Alexander et al.24 What parents and their adolescent sons suggest for male HPV vaccine messaging |

Qualitative (30–60 minutes in-person, semistructured interviews) Parent–son dyads interviewed about how they felt about vaccination uptake and series completion, demographic questionnaire |

Recruited from primary care clinics in Indianapolis, IN, from low- to middle-income families 23 dyads were approached for participation, only 21 participated Parents and sons were interviewed simultaneously, but in separate rooms and interviewers |

21 adolescent males (13–17 years of age) parent–son dyads (42 separate interviews) Sons: Black (n = 14), Hispanic (n = 5), and White (n = 2) ranging from 13 to 17 years of age Parents: Majority were female (n = 17), ranging in age 31–53, majority were single (n = 12), half had at least a high school education (n = 11) |

0% | Sons: Felt it was important for a provider recommendation Side effect of vaccines Sons also noted misinformation (e.g., should get vaccine before sexual initiation, available to males, prevention of STIs, genital warts, and cancer) Parents: Side effects of vaccines and fear for sons' health Doses were spaced too far apart Do not want children to feel like “guinea pigs” Did not receive provider recommendation Cost of HPV vaccine too high Length of three-dose regimen Time since the approval of HPV vaccine |

| 20 | Reiter et al.22 Longitudinal predictors of HPV vaccination among a national sample of adolescent males |

Quantitative Longitudinal (two time points) Web-based, self-administered surveys Part of the HIS study |

Recruited parents through an existing online, national survey of US households (dual-frame sampling approach) Panel maintained by a survey company |

Baseline: 547 parents, 421 sons (11–17 years) Follow-up: 327 parents, 228 sons Parents: 59% younger than 45 years 68% White, 80% married, 60% college education, 84% lived in urban areas, 32% born-again Christian, 52% female Sons: 65% White, 30% 11–12 years, 37% 13–15 years, and 33% 16–17 years |

Baseline: 2% of parents had sons who had initiated the HPV vaccine regimen Follow-up: 6% had sons who received at least one dose of the HPV vaccine 8% had initiated the regimen 4% had received all doses |

Baseline vs. follow-up: 11% did not know enough about the HPV vaccine vs. 23% at follow-up 10% did not receive a doctor recommendation vs. 17% at follow-up 6% thought vaccine is unsafe vs. 10% at follow-up 4% were worried because vaccine is new vs. 8% at follow-up 3% did not have recent doctor appointment vs. 11% at follow-up 23% did not know boys can get HPV vs. 5% at follow-up 6% believed their sons were too young vs. 2% at follow-up 55% who received a recommendation vaccinated son vs. 1% at follow-up |

| 19 | Finney Rutten et al.31 Clinician knowledge, clinician barriers, and perceived parental barriers regarding HPV vaccination: Association with initiation and completion rates |

Quantitative (web-based survey and secondary data extraction) Data reported on 9–18-year-old patients residing in the same 27-county geographic region from 2015 to 2016 |

Recruited from Rochester Epidemiology Project across 27 counties in Olmsted county, MN | 280 providers and nurses from 52 clinic sites (70% providers, 26.8% nurses) 86.1% non-Hispanic White, 13.9% other |

11.407 (11.7%) patients had initiated series 5.267 (43.0%) completed vaccination series within study timeframe |

Clinician-reported barriers: 38.9% incorrectly agreed that genital warts were caused by the same HPV types as cervical cancer 43.2% concerned about vaccine safety 41.8% had difficulty discussing sexuality and STIs 43.6% difficulty adding new vaccine to vaccine schedule Vaccine not required for school admittance (50.4%) Perceived parental barriers: 54% limited HPV knowledge 49.8% parental request of vaccine deferment 48.6% thought child was not at risk for HPV 36.1% parental reluctance to discuss sexuality and STIs 34.7% thought child was too young |

| 19 | Bhatta and Phillips34 HPV vaccine awareness, uptake, and parental and health care provider communication among 11- to 18-year-old adolescents in rural Appalachian Ohio county in the US |

Quantitative longitudinal Secondary data analysis of the self-administered survey, 2012 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System from additional five questions |

Middle school and high school classrooms within a rural county located in Northeast Ohio Appalachia | 674 sons (11–18 years of age) out of 1299 participants (separate male/female statistical analyses) 90.3% were non-Hispanic White 3% were 11 years of age |

0% beginning 62.3% were never vaccinated 3.8% received one dose 1.9% received two doses 0.9% received all three doses |

Sons (24.0%) had less HPV awareness than female counterparts (36.6%) Younger age Lack of communication with parents 42.1% sons knew what the HPV vaccine was 13% parents talked about the HPV vaccine 14.4% physicians talked about the HPV vaccine 11.5% sons reported ever receiving the HPV vaccine |

| 19 | Khurana et al.15 HPV vaccine acceptance among adolescent males and their parents in two suburban pediatric practices |

Cross-sectional quantitative Self-administered surveys completed with parent (<18 years, or by self if 18 years or older) |

Pediatric clinics in suburbs in Maryland between 2011 and 2012 Parents were recruited by pediatricians during medical visits at two private solo visits in pediatric practices in Maryland |

Sons: 154 sons 11–21 years of age (mean age 14.9 years); 71.7% White, 15.1% Asian, 13.2% other Parents: 121 parents (mean age 45.8 years); 72.3% White, 17.6% Asian, and 10.1% other Most were college educated and middle class |

0% | Sons: 15.5% accepted vaccine, 27% did not, 57.4% did not know 38.3% heard of HPV 33.1% heard of the HPV vaccine, 8.5% had family/friends received vaccine 60.5% would accept if it protects against warts Adolescents who were sexually active were 4 × more likely to accept vaccine 61.4% would accept if it protects partners from cervical cancer Parents: 31.9% accepted vaccine, 18.5% did not, 49.6% did not know 90% heard of HPV 81.5% heard of the HPV vaccine 32.8% had family/friends receive vaccine 70.6% would accept if it protects against warts 63.6% would accept if it protects partners from cervical cancer |

| 19 | Alexander et al.29 Parent–son decision-making about HPV vaccination: A qualitative analysis |

Qualitative (30–60 minutes in-person, semistructured interviews) Parent–son dyads asked about decision to vaccinate and physician vaccination recommendation |

Recruited from primary care clinics in Indianapolis, IN, from low- to middle-income families Parents and sons were interviewed simultaneously, but in separate rooms and interviewers |

21 adolescent males (13–17 years of age) parent–son dyads (42 separate interviews) Sons: Black (n = 14), Hispanic (n = 5), and White (n = 2) ranging from 13 to 17 years Parents: Majority were female (n = 17), ranging in age 31–53, majority were single (n = 12), half had at least a high school education (n = 11) |

0% | Parents: Vaccine was optional Questions about sex from son Limited ability to monitor sons' activities Potential risks with the vaccine (n = 2) Physician talked about genital warts Vaccine safety Prevention against cancer and genital warts Availability for males A subset talking about cervical cancer in girls Sons: Pain is most common concern (e.g., get shot in penis) Many felt as though this was the first health care decision that they had been involved in |

| 18 | Agawu et al.37 Sociodemographic differences in HPV vaccine initiation by adolescent males |

Quantitative (retrospective cohort study; medical record extraction) |

Network of primary care practices affiliated with a large metropolitan children's hospital located in Pennsylvania and New Jersey Recruited from preventative or acute appointments |

58,757 sons 11–18 years of age 57.3% non-Hispanic White, 27.6% non-Hispanic Black 76.9% private insurance |

0% beginning Blacks vaccinated most (53.7%), then Hispanics (44.1%), then Whites (33.1%) 20,465 (77.6%) vaccinated within 2 years of first visit 39% initiated overall 6.9% vaccinated at first visit |

No/poor insurance (being on Medicaid or no insurance) Racial subgroups with Medicaid were more likely to initiate vaccine series than those with private insurance Non-Hispanic White participants were less likely to initiate HPV vaccine series Black participants most likely to vaccinate then Hispanics |

| 17 | Liddon et al.39 Provider attitudes toward HPV vaccine for males |

Quantitative, systematic review (secondary data analysis discussing research design and outcomes reported) | HPV vaccine acceptance in males quantitative or qualitative data | 23 published articles (half published in the US) 87% quantitative, 13% qualitative Most used convenience samples (74%) and 26% relied on nationally representative samples |

NA | Providers are likely to recommend the HPV vaccine to male adolescents, but are more likely to recommend it to those 13–18 years of age Most offer the vaccine to males to protect future female partners 59% believe the vaccine would provide an opportunity to discuss sexual health with adolescent patients Younger children are less likely to have preventative health care visits or see physicians for vaccination series 81% adolescent males had either not heard of HPV or had low HPV knowledge |

HIS, HPV Immunization in Sons; HPV, human papillomavirus; N/A, not applicable; NIS, national teen immunization survey; PCP, primary care physician; STI, sexually transmitted infection; US, United States.

Using thematic analysis based on the procedures described by Tong et al.,13 descriptive themes were suggested by authors in isolation (K.D., J.M., and E.S.) and then later discussed as a group. Tong et al.13 posited that there are five main domains of qualitative synthesis: introduction, methodology, literature search/selection, appraisal, and synthesis of findings. This study followed the outline composited by past research13 coding aims, methodology, inclusion criteria, database sources, electronic search strategy, screening (e.g., title, abstract and full-text review) and data extraction, derivation of themes, and rational for appraisal (e.g., supported by past literature) in chronological order.

To further assess study quality, the modified Downs and Black Quality Checklist14 for nonrandomized and randomized studies was used to identify individual included study quality on 27 items regarding reporting, external validity, internal validity, and power with potential scores ranging from 0 to 28, with higher scores indicating better study quality. In accordance with past literature,14 each article was given a quality grade of “excellent” (24–28 points), “good” (19–23 points), or “fair” (14–18 points). This scale has high internal consistency (KR-20 = 0.89) and test-retest reliability (r = 0.88). Study quality ranged from 17 to 25, with an average study quality of 21.4. There were five studies considered “excellent” (21.7%), 16 considered “good” (69.5%), and two considered “fair” (8.6%). There was no study under “fair” range (<14 points) included in this systematic review.

Results

We identified common themes by reviewing the barriers described across studies. The six most common themes were: (1) lack of HPV vaccine awareness/information, (2) misinformation about HPV as a disease, (3) lack of communication, (4) financial concerns relating to uptake, (5) demographic/perceived social norms, and (6) sexual activity.

Lack of HPV vaccine awareness/information

Most articles included in the literature review (n = 19; 82.6%) noted lack of knowledge regarding the HPV vaccine and HPV in general, including among sons (6; 31.5%), parents (13; 68.4%), and providers (5; 26.3%) as a barrier to vaccination. In a study conducted by Khurana et al.,15 50% of adolescent males were unsure or did not want to be vaccinated with the HPV vaccine. Adolescent males also reported additional barriers to enrollment, including slight embarrassment,16,17 fear of side effects and needles, perceived vaccine effectiveness, dosage schedule, low HPV awareness, and perceived low susceptibility to HPV, as reasons not to vaccinate,18,19 in addition to lack of information about the vaccine overall.20–24

Across a number of studies, young adult males believed HPV vaccination was important, but only among those who viewed themselves to be at a higher risk for HPV.18,25 Some parents believed that the vaccine was more relevant when their sons reached 9–17 years of age, but a subset of this group did not wish for their children to be vaccinated because of vaccine side effects and/or because vaccination is not treated as routine for school admittance.26 Beliefs concerning the HPV vaccine were also reported by parents, such as believing the HPV vaccine is experimental (15.1%), the vaccine causes HPV infection (7.1%), and even that it is better to get the disease and recover naturally (4.4%).27 In some studies, however, up to 89% of parents had never heard of an HPV vaccine for males.20–23 Many parents also noted young age20,22,28,29 as a reason not to vaccinate.

Other studies, stemming from parental and adolescent son viewpoints, noted concerns for vaccine safety.16,22,27,28 Providers reported struggling to make vaccine recommendations because the HPV vaccine was not required for school admittance, they had doubts about vaccine safety,16,30–32 and it was difficult to add more vaccines to age-oriented vaccine schedules.30

Misinformation about HPV

Misinformation regarding HPV itself was reported by parents (n = 6, 30%), AYA males (n = 3, 15.7%), and providers (n = 1, 5%). Parents reported inaccurate information or lack of knowledge regarding HPV, including what it is, how it is spread, and the consequences.20,22,24,29

As many as 54% of AYA males believed that HPV only occurred in females.16,33 Bhatta and Phillips34 found that HPV knowledge and awareness increased28 significantly as adolescent boys aged. Providers also reported a lack of knowledge regarding HPV risk among their AYA male patients.34 Providers also had their own knowledge limitations with one study reporting 12% of providers lacking knowledge on when to administer HPV to AYA males and how to have conversations with their patients and their parents regarding HPV.32

Lack of communication

Eleven articles (47.8%) reported communication barriers to vaccine uptake. Many providers noted difficulty communicating the importance of completing the HPV vaccine regimen among this population.30–32 A number of studies noted that providers did not recommend the HPV vaccine or raise awareness due to language differences33 or personal embarrassment.30,31 Within some studies, providers reported personal discomfort talking about STIs with parents and adolescent males.16,30 Parents, however, either did not ask about the HPV vaccine or HPV24 and/or had providers who never recommended the vaccine at all,20,23,35 especially if their own HPV knowledge was low.24

A small group of parents expressed a desire to communicate with providers in their native language, especially if from Hispanic or Ethiopian backgrounds, explaining that they did not trust providers about these topics when speaking in English.33

Financial concerns relating to uptake

A total of seven articles outlined financial barriers to HPV vaccination (30.4%). Both AYA males and their parents reported financial concerns as a main deterrent to the HPV vaccine, including the cost of the vaccine both out of pocket and using insurance.16,29,35 Having no or poor insurance17,23 or a household income lower than $75,00015 were notable factors in low vaccination rates. Some insurance companies did not cover the HPV vaccine for adolescent males because it was not viewed as routine36,37 or thought that this population was less susceptible to HPV infections.31 The out-of-pocket cost of all doses of the HPV vaccine was prohibitive for some parents,16,29,30 as was the cost of doctor appointments to receive the vaccine regimen17,21,23; this burden was compounded for families with multiple children.20,36

Providers argued that the out-of-pockets cost of the HPV vaccine was unaffordable for some populations due to low insurance coverage and impacted uptake rates.31,32 In addition, physicians also face low reimbursement rates from health care insurance companies and subsequent age restrictions on HPV vaccines,38 limiting the reach of such vaccines to older AYAs.

Demographic/perceived social norms

Seven articles (30.4%) mentioned race/ethnicity, native language, and cultural norms of parent respondents as perceived barriers relating directly to lax HPV vaccination uptake. Caucasian parents, although less likely to initiate the vaccine regimen, as opposed to African American or Hispanic participants,22,29,36,37,39 were more knowledgeable regarding HPV and the vaccine, but only after discussing this with a provider.26,41 Another study noted that Asian males were less likely to be open to vaccination compared to their Caucasian or African American counterparts.15 English-speaking parents were less likely to believe the vaccine is necessary compared with non-English speaking parents.23 Adolescents who were older had significantly higher rates of uptake than younger adolescents.34

Related to parental demographics, cultural or community norms impacted vaccine uptake.42 Schuler and Coyne-Beasley43 found that parents whose friends or community vaccinated their sons were over four times more likely to vaccinate their own sons within the next year. In addition, Oldach and Katz42 noted that 4.4% of providers stated that they did not recommend the HPV vaccine to families who they knew held specific religious beliefs. Community location was also found to be an important barrier to HPV education42 and related to access to health care.16,22,24,30,37 In rural communities in the US with lower socioeconomic status,15 providers report that discussion of a sexually oriented disease and possible prevention strategies, like a vaccine, was viewed negatively by community members.42

Sexual activity

The sexual contraction of HPV infections remains a relevant barrier to vaccine uptake within some adolescent males. Oldach and Katz42 found that 15.6% of providers, in more conservative areas15 of the US, were worried that the HPV vaccine initiation and completion would encourage sexual activity, and therefore refused to recommend the vaccine.23 A minority of adolescent males (8.1%) claimed that embarrassment of receiving a vaccine related to sexually involved diseases was enough to stop them from initiating the regimen.23 A small portion of studies found that parents were concerned with their sons becoming sexually active,23,27 and were less likely to begin or complete the three-dose regimen. Furthermore, some parents refused the vaccine because their son was not currently sexually active, but expressed intention to vaccinate them once they became sexually active23,35 in the future.

Embarrassment was noted for parents in a small group of studies, finding that introducing the sexually oriented conversation about their son was awkward.16,17 The results of one study suggest, however, that sexual activity may act as a facilitator to HPV vaccination. Khurana et al.15 found that a subset of AYA males who were sexually active were four times more likely to be open to receiving the vaccine regimen than those who were not sexually active. While some parents and AYA males do not vaccinate due to the beliefs surrounding sexual activity, the results of this review suggest that this is not a primary barrier to vaccine uptake, and in some cases may act as a facilitator.

Study quality score and publication date

A vast majority (69.5%) of studies included in this review were considered of “good” study quality, while 21.7% were considered “excellent,” and only 8.6% considered “fair.” The studies that scored in the “excellent” range were more recent, mainly from 2015 to 2017, with only two from 2012. Similarly, the study with the lowest study quality score of 17 was also the oldest included study, published in 2010. Most of these studies were recently published, ranging from 2014 to 2017, with a few in 2012 to 2013, and only one from 2011.

Discussion

This literature review provides a perspective on how the barriers of the HPV vaccine vary between AYA males, their parents, and providers. Moreover, there are areas that remain unexplored that deserve attention. Most articles outlined how vaccination uptake for HPV prevention, especially among AYA males, remains uncommon due to barriers from adolescents', parents', and providers' point of views. Generally, it can be suggested that the HPV vaccine uptake to prevent HPV infection among AYA males is lacking within the US. Instead of focusing solely on specific groups (i.e., adolescents, parents, or providers), it is imperative to outline common barriers and differences among these groups to further target interventions and policy changes regarding vaccination uptake among this population.

Parents, providers, and AYA males have different perspectives on potential facilitators or barriers to HPV vaccination. Among young adult males, the HPV vaccine was important to those who perceived themselves to be at increased risk for HPV,18,25 but they report several barriers to vaccination, including fear of side effects, fear of needles, perceived vaccine effectiveness, need for multiple shots, perceived susceptibility to HPV, difficulty scheduling an appointment, and HPV awareness/knowledge.18,19 Adolescents reported slight embarrassment23,32 and overwhelming misinformation20–24 as being the top reasons not to vaccinate against HPV.

The perspectives of all parties involved in these discussions are important because although vaccination intent was present in many parents, vaccination rates continue to remain low.41 For instance, in a study conducted by Dempsey et al., parents believed that having their sons receive the HPV vaccine was important (62%), but only when their sons were between 9 and 17 years of age.26 A subsection of parents believed that receiving the HPV vaccine would increase sons' sexual activity at a younger age.23 Misconceptions regarding HPV and available vaccines also stemmed from parental demographics, belief systems,42 and community pressures causing the vaccine's safety to come into question.27,29,32,40,42 Generally, Caucasian parents were more knowledgeable than African American parents regarding the HPV vaccine, but only after discussing the vaccine with a provider.26,41

It is possible that regions of the US,23 socioeconomic status,15 access to health care,16,22,24,30,37 and community norms20,29,42 have some impact on HPV knowledge and vaccine recommendations to parents and their sons. Future research should target various regions of the country and families of different socioeconomic statuses and backgrounds to fully encompass how these misconceptions can cause failure of HPV vaccine uptake or completion of the three-dose regimen among this population.

Providers, additionally, were also found to hold many misconceptions among this population, but the reasons for these misconceptions remain unclear. Many providers failed to recommend the vaccine or introduce HPV information,20,23,35 possibly due to language differences33 that may make it more difficult to begin or sustain this conversation, or due to personal embarrassment regarding the subject.30,31 While this may have been noted in this review as a barrier, the World Health Organization (WHO) has introduced avenues to reduce embarrassment of all parties by suggesting the recommendation of the HPV vaccine as a cancer-preventative vaccine, removing the sexual nature of its origins, especially to younger patients.44

Providers' recommendations remain imperative for the HPV vaccine uptake among this population,38 but providers perceive numerous barriers to this discussion, including health care reimbursement and age-related barriers such as fears around increasing sexual activity.38 While fears of increased sexual activity were noted among few studies further included in this review, this lapse is equivalent to what was found in previous literature and should be identified within future research. Despite widespread recommendations by providers45 and clinical guidelines,46,47 many AYA males remain unvaccinated against HPV. If providers begin talking to adolescents at the age of nine, the youngest age recommended for beginning the HPV vaccine three-dose regimen, they may be too young to understand what it is for and its importance.20,22,23

It may be more beneficial to introduce the vaccine to the parents, and in addition, educate both parent and child about HPV and the HPV vaccine before scheduling or administering the vaccination. Increasing communication about HPV and its vaccination between these groups may increase uptake rates within this population over time. To discover the most beneficial avenues of communication between parents, providers, and AYA males, future research should examine what communication methods are associated with male willingness to be vaccinated and completion of the HPV vaccine three-dose regimen.

It is apparent that lack of communication between all parties may rely on preconceived notions about who should initiate the conversation about HPV and its prevention. Overwhelmingly, parents would not ask about HPV or the HPV vaccine regarding their AYA sons,24 possibly not knowing enough about the subject to do so. Embarrassment, especially in the presence of adults, may stem from the sexually oriented conversation at doctors' appointments, possibly with parental overview.16,17 HCPs have the ability to influence vaccination uptake among adolescent males and their families. Brewer47 discussed that vaccinating urgently, listing the HPV in the middle of recommended vaccines, noting child's risk, and easing parent concern all increased vaccination uptake drastically, more so than the unstructured current process.

HCP training, as related to HPV vaccination uptake among adolescent males, has been few and far between. Yarwood and Bonanni48 have discussed training avenues to improve HPV vaccination uptake, including 30% improvement by verbal recommendation. Continuing education for HCPs in vaccinology, allowing questions during office visits, comprehendible materials, and the use of layterms when speaking with patients and their parents are imperative for vaccination uptake.48 More information is required to pinpoint exact causes of misinformation among parents and providers to better understand these phenomena.

This review must be interpreted considering its limitations. The search results may have been updated through the editing process, making it possible that additional articles may be published now, which could have been included in this review. Some relevant articles may have been missed, which were published in press, dissertations, conference proceedings, and/or results not yet published. In addition, it is possible that policy and legislation concerning vaccination and HPV among this population have changed since this review. Since this review only included US studies, generalizability to other countries and areas outside of the US remain limited.

Implications and Future Directions

HPV-related cancers are increasing, and therefore, increasing vaccination is imperative.2,49 For instance, HPV-associated oropharynx cancer incidence has increased 225% over the past three decades.2 Barriers associated with HPV vaccination include AYA embarrassment as well as lack of provider knowledge regarding this specific population. This is particularly concerning, as provider recommendation is one of the most important factors for vaccination uptake. Increasing provider knowledge may be imperative for reducing incidence of HPV-related cancers as well as improving lines of communication between all groups.

Future health policy should focus on involving the HPV vaccine as one of the vaccines adolescents require before enrollment in school within the US. Future research should also identify which groups and regions of the US have lowest HPV vaccination uptake rates overall and make the vaccine more accessible and affordable in those locations.48–53 In addition, HCP communication methods should be studied to identify ideal comfort for the HCP and patient.53 Policy should influence how HCPs recommend specific vaccines, such as the HPV vaccine, and should be trained to do so, to further increase vaccination uptake among this population.

Conclusions

Evidence suggests the HPV vaccine is an effective vaccination against cancer and genital warts in AYA males, but AYA males, their parents, and providers report many barriers to vaccination. While parents, providers, and adolescent males may differ in relation to their barriers, they did show many similar traits, including fear of side effects,15 HPV awareness/knowledge,18,19,50 financial costs,15,36,51,52 and changes in sexual activity.38 It remains imperative to increase communication between these groups to facilitate more discussion regarding HPV and the HPV vaccine among this population in hopes of increasing the number of males fully vaccinated to protect themselves and future partners.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank our second outside reviewer (Abdul Khaleque) for his role in reviewing our completed project.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Incidence, prevalence, and cost of sexually transmitted infections in the United States; 2013. Accessed January23, 2019 from: https://npin.cdc.gov/publication/incidence-prevalence-and-cost-sexually-transmitted-infections-united-states

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevalence of HPV in adults aged 18–69: United States, 2011–2014; 2017. Accessed March14, 2019 from: https://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stats.htm

- 3. Han JJ, Beltran TH, Song JW, et al. . Prevalence of genital human papillomavirus infection and human papillomavirus vaccination rates among US adult men: national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) 2013–2014. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(6):810–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moscicki AB, Palefsky JM. HPV in men: an update. J Low Genit Tract Disord. 2011;15(3):231–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tsai T. How many men have HPV? Population reference bureau; 2016. Accessed February23, 2019 from: www.prb.org/Publications/Articles/2011/hpv-in-men.aspx

- 6. Daley MF, Liddon N, Crane LA, et al. . A national survey of pediatrician knowledge and attitudes regarding human papillomavirus vaccination. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):2280–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Das R. Effectiveness, immunogenicity, and safety of HPV in pre-adolescents and adolescents–10 years of follow-up. Adolesc Heal. 2016;58:S10 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fisher KA, Cahill L, Tseng TS, Robinson WT. HPV vaccination coverage and disparities among three populations at increased risk for HIV. Transl Cancer Res. 2016;5(S5):S1000–6 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Knudtson MA. The effects of a HPV educational intervention aimed at collegiate males on knowledge, vaccine intention, and uptake. Evid Based Pract Proj Rep. 2017;100:1–117 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Radisic G, Chapman J, Flight I, Wilson C. Factors associated with parents' attitudes to the HPV vaccination of their adolescent sons: a systematic review. Prev Med (Baltim). 2017;95:26–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Saslow D, Andrews KS, Manassaram-Baptiste D, et al. . Human papillomavirus vaccination guideline update: American Cancer Society guideline endorsement. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(5):375–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wong LP, Edib Z, Alias H, et al. . A study of providers' experiences with recommending HPV vaccines to adolescent boys. J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;37(7):937–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, et al. . Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12(1):181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality of both randomised and non-randomised studies of health care. J Epidemiol Community Heal. 1998;52:377–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Khurana S, Sipsma HL, Caskey RN. HPV vaccine acceptance among adolescent males and parents in two suburban pediatric practices. Vaccine. 2015;33(13):1620–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reiter PL, McRee AL, Kadis JA, Brewer NT. HPV vaccine and adolescent males. Vaccine. 2011;29(34):5595–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Reiter PL, McRee AL, Pepper JK, Brewer NT. Default policies and parents' consent for school-located HPV vaccination. J Behav Med. 2012;35(6):651–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Newman PA, Logie CH, Doukas N, Asakura K. HPV vaccine acceptability among men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2015;89(7):568–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Reiter PL, Brewer NT, Smith JS. Human papillomavirus knowledge and vaccine acceptability among a national sample of heterosexual men. Behaviour. 2010;86(3):241–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Calo WA, Gilkey MB, Shah P, et al. . Parents' willingness to get human papillomavirus vaccination for their adolescent children at a pharmacy. Prev Med (Baltim). 2017;99:251–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cates JR, Ortiz R, Shafer A, et al. . Designing messages to motivate parents to get their preteenage sons vaccinated against human papillomavirus. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2012;44(1):39–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Reiter PL, McRee AL, Pepper JK, et al. . Longitudinal predictors of human papillomavirus vaccination among a national sample of adolescent males. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(8):1419–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reiter PL, Brewer NT, Gilkey MB, et al. . Early adoption of the human papillomavirus vaccine among Hispanic adolescent males in the United States. Cancer. 2014;120(20):3200–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Alexander AB, Stupiansky NW, Ott MA, et al. . What parents and their adolescent sons suggest for male HPV vaccine messaging. Heal Psychol. 2014;33(5):448–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Crosby RA, DiClemente RJ, Salazar LF, et al. . HPV for guys: correlates of intent to be vaccinated. J Mens health. 2011;8(2):119–25 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dempsey AF, Butchart A, Singer D, et al. . Factors associated with parental intentions for male human papillomavirus vaccination: results of a national survey. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;38(8):769–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tan TQ, Gerbie MV. Perception, awareness, and acceptance of human papillomavirus disease and vaccine among parents of boys aged 9 to 18 years. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2017;56(8):737–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Griebeler M, Feferman H, Gupta V, Patel D. Parental beliefs and knowledge about male human papillomavirus vaccination in the US: a survey of a pediatric clinic population. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2012;24(4):315–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Alexander AB, Stupiansky NW, Ott MA, et al. . Parent-son decision-making about human papillomavirus vaccination: a qualitative analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Farias AJ, Savas LS, Fernandez ME, et al. . Association of providers perceived barriers with human papillomavirus vaccination initiation. Prev Med (Baltim). 2017;105:219–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Finney Rutten LJ, Sauver JL, et al. . Clinician knowledge, clinician barriers, and perceived parental barriers regarding human papillomavirus vaccination: association with initiation and completion rates. Vaccine. 2017;35(1):164–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Luque JS, Tarasenko YN, Dixon BT, et al. . Recommendations and administration of the HPV vaccine to 11- to 12-year-old girls and boys: a statewide survey of Georgia vaccines for children provider practices. J Low Genit Tract Disord. 2014;18(4):298–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Greenfield LS, Page LC, Kay M, et al. . Strategies for increasing adolescent immunizations in diverse ethnic communities. J Adolesc Heal. 2015;56(5):S47–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bhatta MP, Phillips L. Human papillomavirus vaccine awareness, uptake, and parental and health care provider communication among 11- to 18-year-old adolescents in a rural Appalachian Ohio county in the United States. J Rural Heal. 2015;31(1):67–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Thompson EL, Rosen BL, Vamos CA, et al. . Human papillomavirus vaccination: what are the reasons for nonvaccination among U.S. adolescents? J Adolesc Heal. 2017;61(3):288–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. PL, McRee AL, Pepper JK, et al. . Improving human papillomavirus vaccine delivery: a national study of parents and their adolescent sons. J Adolesc Heal. 2012;51(1):32–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Agawu A, Buttenheim AM, Taylor L, et al. . Sociodemographic differences in human papillomavirus vaccine initiation by adolescent males. J Adolesc Heal. 2015;57(5):506–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Allison MA, Dunne EF, Markowitz LE, et al. . HPV vaccination of boys in primary care practices. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13(5):466–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liddon N, Hood J, Wynn BA, Markowitz LE. Acceptability of human papillomavirus for males: a review of the literature. J Adolesc Heal. 2010;46(2):113–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schuler CL., DeSousa NS., Coyne-Beasley T. Parents' decisions about HPV vaccine for sons: The importance of protecting sons' future female partners. J Comm Health. 2014;39:842–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Perkins RB, Clark JA. Providers' perceptions of parental concerns about HPV vaccination. J Healthc Poor Underserved. 2013;24(2):828–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Oldach BR, Katz ML. Ohio Appalachia public health department personnel: human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine availability, and acceptance and concerns among parents of male and female adolescents. J Community Med Health Educ. 2012;37(6):1157–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schuler CL, Coyne-Beasley T. Has their son been vaccinated? Beliefs about other parents matter for human papillomavirus vaccine. Am J Mens Health. 2016;10(4):318–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. World Health Organization (WHO). Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine background paper; 2008. Accessed December23, 2018 from: https://www.who.int/immunization/diseases/hpv/en/

- 45. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Recommendations on the use of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in males—advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP). Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;50:1705–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Giuliano AR. Human papillomavirus vaccination in males. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;107(S1):S24–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Petrosky E, Bocchini JA, Hariri S, et al. . Use of 9- valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: updated HPV vaccination recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(11):300–4 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Brewer NT. Effectiveness of training providers to improve their recommendations. In: Meeting of the prevention and control of HPV and HPV-related cancers. Romania: President of the United States' Cancer Panel; 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yarwood J, Bonanni P. HCP training in service and pre-service. In: Meeting of the Prevention and Control of HPV and HPV-Related Cancers. Romania: President of the United States' Cancer Panel; 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gattoc L, Nair N, Ault K. Human papillomavirus vaccination: current indications and future directions. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2013;40(2):177–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Eaton EF, Kulczycki A, Saag M, et al. . Immunization costs and programmatic barriers at an urban HIV clinic. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(11):1726–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gostin LO. Mandatory HPV vaccination and political debate. JAMA. 2011;306(15):1699–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Vadaparampil ST, Murphy D, Rodriguez M, et al. . Qualitative responses to a national provider survey on HPV vaccination. Vaccine. 2013;31(18):2267–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]