Abstract

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a progressive disease with a high mortality rate. Previous studies have revealed the important function of the β3 adrenergic receptor (β3-AR) in cardiovascular diseases, and the potential beneficial effects of numerous β3-AR agonists on pulmonary vasodilation. Conversely, a number of studies have proposed that the antagonism of β3-AR may prevent heart failure. The present study aimed to investigate the functional involvement of β3-AR and the effects of the β3-AR antagonist, SR59230A, in PAH and subsequent heart failure. A rat PAH model was established by the subcutaneous injection of monocrotaline (MCT), and the rats were randomly assigned to groups receiving four weeks of SR59230A treatment or the vehicle control. SR59230A treatment significantly improved right ventricular function in PAH in vivo compared with the vehicle control (P<0.001). Additionally, the expression level of β3-AR was significantly upregulated in the lung and heart tissues of PAH rats compared with the sham group (P<0.01), and SR59230A treatment inhibited this increase in the lung (P<0.05), but not the heart. Specifically, SR59230A suppressed the elevated expression of endothelial nitric oxide and alleviated inflammatory infiltration to the lung under PAH conditions. These results are, to the best of our knowledge, the first to reveal that SR59230A exerts beneficial effects on right ventricular performance in rats with MCT-induced PAH. Furthermore, blocking β3-AR with SR59230A may alleviate the structural changes and inflammatory infiltration to the lung as a result of reduced oxidative stress.

Keywords: pulmonary arterial hypertension, β3 adrenergic receptor, SR59230A, heart function, endothelial nitric oxide synthase

Introduction

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is hemodynamically characterized by a progressive elevation in pulmonary vascular resistance and the loss of pulmonary arterial compliance, giving rise to excessive right ventricular (RV) afterload. This ultimately results in abnormal vascular remodeling, RV hypertrophy and heart failure (1). In addition to the abnormal proliferation of pulmonary artery endothelial and smooth muscle cells, it has been revealed that factors contributing to the progressive narrowing of the distal pulmonary arterioles include inflammation, in situ thrombosis and an imbalance in the expression of various endothelial vasoactive mediators; this includes the reduced production of nitric oxide (NO) and prostacyclin, and the increased production of endothelin (ET)-1. Therapies targeting the prostacyclin, ET-1 or NO pathways have resulted in substantially improved outcomes in patients with PAH (2). However, current treatment strategies remain insufficient, with substantial hemodynamic and functional impairments that cause considerable morbidity (3). Therefore, novel therapeutic approaches are urgently required.

The β3-adrenergic receptor (β3-AR), first identified in 1989, has been demonstrated to serve an important function in heart failure, hypertension, obesity, diabetes and coronary artery disease, which is independent of the stimulation effects of the β1- and β2-ARs (4,5). Unlike β1- and β2-AR, which produce positive chronotropic and inotropic effects upon stimulation, β3-AR imparts a marked reduction in cardiac contractility by activating endothelial NO synthase (eNOS), resulting in the subsequent release of NO from cardiac myocytes (6,7). Upregulation of β3-AR has been observed in the myocytes of animal heart failure models in addition to patients with heart failure (8,9). Nevertheless, the β3-AR responses have been revealed to vary considerably between species (10), and the efficacy of β3-AR pharmacotherapy may depend on a number of factors, including the severity of heart failure and the therapeutic time interval (11,12).

β3-AR activation is able to influence the vasodilation of specific blood vessels in humans and animal models (13–15). However, conflicting results have proposed the antagonism of β3-AR as a potential preventative strategy for the development of heart failure (9,16). Due to the lack of evidence for the existence of β3-AR in the pulmonary artery (17,18), few studies have reported a β3-adrenergic response in PAH. Indeed, emerging technologies were at the forefront of this research area when a rat RNA-Seq transcriptomic BodyMap across 11 organs confirmed the expression of β3-AR in rat adrenal, thymus, heart and lung tissues (19). An additional study revealed that β3-AR was expressed in the human pulmonary artery (20), and that the β3-AR agonist BRL37344 reduced pulmonary vascular resistance and improved RV performance in a porcine chronic pulmonary hypertension model. A further study indicated that nebivolol, a β3-adrenergic agonist, reduced the overexpression of growth and inflammatory mediators in pulmonary vascular cells harvested from patients with PAH (21). However, BRL37344 and nebivolol are not selective β3-AR agonists, therefore their effects may result from the stimulation of alternative β-ARs (22,23). Apart from a limited number of studies using β3-AR antagonists to block the effect of β3-AR agonists (24,25), no studies have been reported to investigate the antagonism of β3-AR alone in PAH.

The present study established a rat PAH model, which was treated with the selective β3-AR antagonist, SR59230A, to investigate the functional involvement of β3-AR in hemodynamic and morphological impairment in PAH, and identify novel therapeutic targets. The generation of two isoforms of NOS following β3-AR inhibition were also investigated, investigating the potential signaling pathways of β3-AR in PAH.

Materials and methods

Animals

In total, 12 male Sprague-Dawley rats (weight, 250–300 g; age, 8 weeks) were purchased from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University (Harbin, China). The present study was ethically approved by the Harbin Medical University Committee on Animal Care (26) and was performed in adherence with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines on the Use of Laboratory Animals (27). The rats were randomly assigned to three groups receiving: i) An equal volume of solvent (vehicle, 1 ml/kg body weight); ii) a single subcutaneous injection of monocrotaline (MCT; 80 mg/kg body weight; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) to induce PAH within 4 weeks; or iii) a single injection of MCT and injections of SR59230A (2 mg/kg body weight; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) every other day for 4 weeks. Injections of SR59230A or an equal volume of solvent were administered via the tail vein of the rat.

In vivo Doppler echocardiography

Subsequent to 4 weeks of MCT administration, the rats were anesthetized using isoflurane. The isoflurane vaporizer was adjusted to 3–5% for induction and 1–3% for maintenance. The animals were stabilized in the supine position, and M mode echo recordings from the parasternal long-and short axes were collected. All measurements were subsequently analyzed using Vevo 770 software (Fujifilm VisualSonics Inc.).

Tissue fixation, embedding and sectioning

Following the in vivo Doppler echocardiograph, the rats were euthanized by continuous isoflurane exposure (5%). Following dissection, rat RV and left lung tissues were immediately fixed in 4% formaldehyde solution for 24 h at room temperature. The tissues were dehydrated by immersion in increasing concentrations of ethanol (from 70 to 90%, and then from 90 to 100% ethanol). Each dehydration step lasted for 1 h. The dehydrating agent was subsequently cleared by incubation in xylene for 2 h at room temperature prior to paraffin embedding. Paraffin was typically heated to 60°C and then allowed to harden overnight, and the tissues were sectioned to 8 µm using a microtome.

Histological characterization-hematoxylin and eosin staining

Tissue sections were deparaffinized through three changes of xylene and hydrated using distilled water. Subsequent to rinsing, the slides were stained with hematoxylin for 2 min, rinsed again, dipped in ammonia hydroxide solution (0.2%) until a blue color change was observed, and washed once more. The slides were then counterstained with eosin for 10 min and dehydrated with 95% ethanol, followed by three changes of 100% ethanol. The dehydrated slides were then cleared with three changes of xylene and mounted onto a coverslip with Neutral Canada balsam. All the staining solutions were incubated with the samples at room temperature.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and semi-quantitative analysis

Tissue sections were incubated three times in xylene (5 min each at room temperature), followed by two washes each with 100, 95 and 80% ethanol for 10 min, and two washes in distilled water for 5 min each. Following deparaffinization and rehydration, antigen retrieval was performed using a pressure cooker. First, the appropriate antigen retrieval buffer (10 mM sodium citrate, 0.05% Tween-20, pH 6.0) was added to the pressure cooker. Once the boiling temperature was reached (95-100°C), the sections were then submerged using forceps and the pressure cooker lid was secured. The cooker as allowed to reach maximum pressure prior to depressurization, and was subsequently filled with cold water for 10 min. The sections were then transferred to phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) prior to incubation with a blocking buffer [1X PBS, 5% goat serum (cat. no. ab7481; Abcam) and 0.3% Triton™ X-100] at room temperature for 30 min. Subsequently, the sections were incubated with an anti-β3-AR primary antibody (cat. no. ab94506; Abcam; working concentration, 10 µg/ml) overnight at 4°C. The sections were washed three times in PBS for 5 min each, and incubated with a secondary antibody anti rabbit (cat. no. PV-9001; dilution, 1:2,000; Beijing Zhongshanjinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) in the dark at 37°C for 20 min. Following three additional washes in PBS, the sections were incubated in 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB)-peroxidase substrate solution for 5–10 sec (cat. no. ZLI-9017; Beijing Zhongshanjinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), and washed in PBS once again. The sections were then counterstained with hematoxylin for 2 min at room temperature, dehydrated through two changes of 95% ethanol and three changes of 100% ethanol, cleared with three washes in xylene and mounted on a coverslip with Neutral Canada balsam.

The IHC images were obtained (Olympus, BX51; light microscope; magnification, ×200) and analyzed using the FIJI analysis software (ImageJ win64; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Run Image > Color > Color Deconvolution was performed and ‘H DAB’ from the Vectors pull-down was selected as the stain. The three image windows (colors 1, 2 and 3) corresponded to hematoxylin, DAB and residual (which should be close to white if the separation is optimal), respectively. DAB positivity was quantified in units of intensity and normalized to the Sham group.

RNA extraction and reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from the frozen lung tissue samples (50–100 mg) using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and isolated using the RNeasy® Plus Mini kit (Qiagen GmbH). The RNA quality and concentration were measured using a Nanodrop 2000 (NanoDrop Technologies; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Total RNA (2 µg) was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The RT reaction was incubated at 25°C for 10 min, at 37°C for 2 h and at 85°C for 5 min. The mRNA expression levels of the β3-AR, eNOS and inducible NOS (iNOS) were determined by RT-qPCR. The thermocycling conditions were as follows: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec, 55°C for 10 sec and 72°C for 15 sec. qPCR was performed using a reaction mixture containing SYBR® Green dye (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) on a StepOnePlus PCR system (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Using these systems, relative alterations in mRNA levels were calculated according to the ΔΔCq formula (28). β-actin was used as an internal control. The primer sequences are listed in Table I.

Table I.

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction primers sequences.

| Gene | Primers |

|---|---|

| β3-AR | F: AGAACTCACCGCTCAACAGG |

| R: CAGAAGTCAGGCTCCTTGCTA | |

| eNOS | F: GAAGACTGAGACTCTGGCCC |

| R: CCGTGGGGCTTGTAGTTGAC | |

| iNOS | F: GGCTGAGTACCCAAGCTGAG |

| R: ATTGTGGCTCGGGTGGATTT | |

| β-Actin | F: CACTTTCTACAATGAGCTGCG |

| R: CTGGATGGCTACGTACATGG |

F, forward; R, reverse; β3-AR, β3-adrenergic receptor; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase.

Western blotting

The lung tissues were homogenized and total protein was extracted using ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer with protease inhibitor mix (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). Protein was quantified using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) Equivalent amounts of protein (50 ug/well) were separated using SDS-PAGE with a 12% gel, and the proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, which were blocked using Tris-buffered saline with TBS-Tween (0.1% Tween-20) with 5% non-fat milk for 1 h. The membranes were then incubated with primary antibodies against eNOS (cat. no. ab5589; 1:1,000; Abcam) and iNOS (cat. no. ab15323; 1/250; Abcam) at 4°C overnight and washed 3 times with TBST prior to incubation with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (cat. no. ab6721; 1:2,000; Abcam) at room temperature for 1 h. β-actin was used as an internal control (cat no. ab115777; 1:200; Abcam). The blots were washed and developed using a HRP substrate solution (EMD Millipore), and the ChemiDoc XRS+ system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) was used for imaging and FIJI analysis software (ImageJ win64; National Institutes of Health) was used for image processing and analysis. Each experiment was repeated in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc.) and expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean. One-way analysis of variance was used to compare the differences between groups, and P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

β3-AR antagonist SR59230A improves RV performance in an MCT-induced PAH rat model

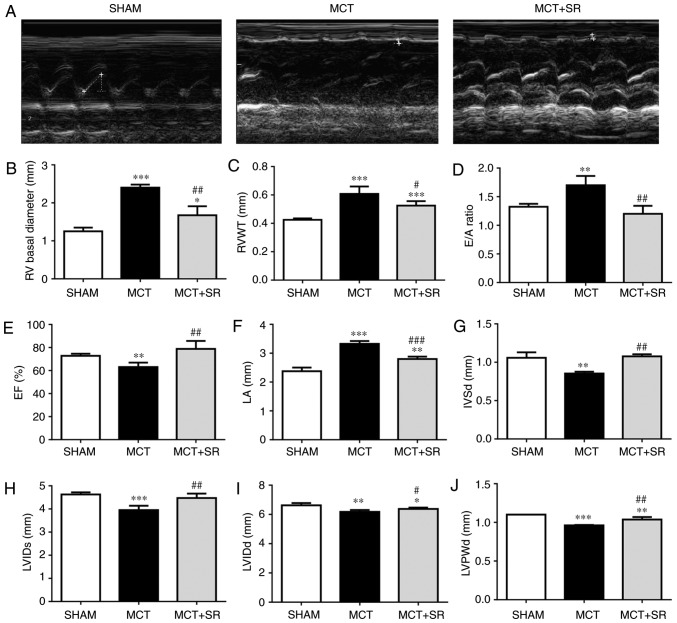

Echocardiography was performed on each rat and the heart function was evaluated in all groups 4 weeks subsequent to MCT administration; representative M-mode echocardiographic images (Fig. 1A) reveal the RV function and structure in the three groups. Significant increases in RV basal diameter (P<0.001), RV wall thickness (RVWT; P<0.001) and E/A ratio [the ratio of peak velocity flow in early diastole (the E wave) to peak velocity flow in late diastole caused by atrial contraction (the A wave)] (P<0.01), and a significant decrease in the RV ejection fraction (EF) (P<0.01) were observed in MCT-injected rats compared with the sham group, indicating that the MCT-induced PAH model had been successfully established. The MCT rats that had received SR59230A (MCT+SR) exhibited a significant decrease in RV basal diameter, E/A ratio (P<0.01) and RVWT (P<0.05), with considerable recovery of the EF (P<0.01) compared with the MCT-induced PAH rats (Fig. 1B-E). In addition, SR59230A treatment significantly reduced the left atrial diameter compared with the MCT group (P<0.001), which was significantly higher (P<0.001) in the MCT-induced PAH model compared with the sham group (Fig. 1F). Furthermore, compared with the sham rats, MCT-induced PAH rats displayed slight, but significant (P<0.01) decreases in left ventricular internal diameter (LVID) systole (LVIDs), LVID diastole (LVIDd), left ventricular posterior wall thickness at end-diastole (LVPWd) and interventricular septal end diastole (IVSd), all of which were slightly recovered following SR59230A administration (P<0.05; Fig. 1G-I).

Figure 1.

β3-AR antagonist SR59230A improves right ventricular performance in MCT-induced PAH. (A) Representative M-mode echocardiographic images were taken at the midventricular level (parasternal long axis). Quantification of (B) basal RV diameter, (C) RVWT, (D) E/A ratio, (E) right ventricular EF, (F) LA diameter, (G) IVSd, (H) LVIDs, (I) LVIDd and (J) LVPWd from sham, MCT and MCT+SR rats 4 weeks following MCT administration. N=4 per group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. Sham. #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 vs. the MCT group. β3-AR, β3-adrenergic receptor; PAH, pulmonary artery hypertension; RV, right ventricular; RVWT, right ventricular wall thickness; EF, ejection fraction; LA, left atrial; IVSd, Interventricular septal end diastole; LVIDs, left ventricular internal diameter end systole; LVIDd, left ventricular internal diameter end systole; LVPWd, left ventricular posterior wall thickness at end-diastole; MCT, monocrotaline; MCT+SR, MCT + SR59230A.

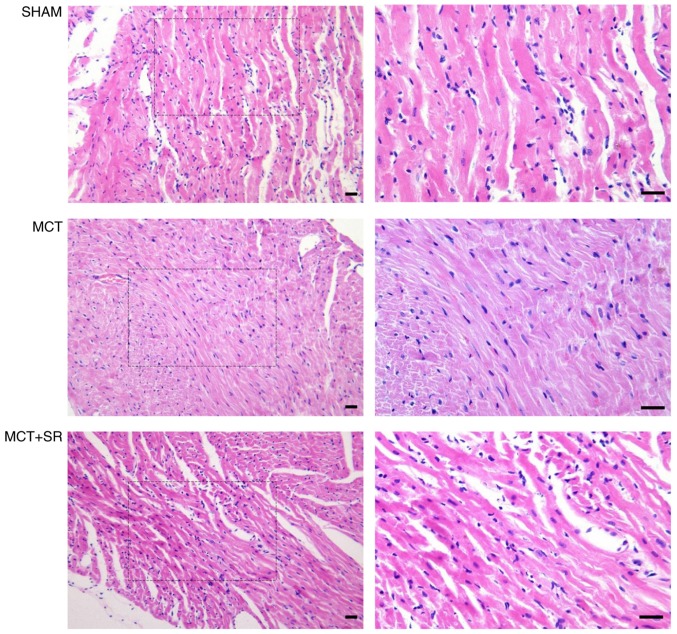

SR59230A reduces MCT-induced RV hypotrophy

Histological examination of hematoxylin and eosin-stained RV sections revealed that MCT administration resulted in considerable alterations to the myocardial structure in rats (Fig. 2). RV samples from healthy control rats exhibited the cardiac syncytia of myocardial fibers with central nuclei, while RV from the MCT-treated rats exhibited contracture cardiomyocyte damage, hypereosinophilia, wavy arrangement of the myofibers and cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Moderate macroscopic hypertrophy and reduced inflammatory cell infiltration were observed in sections from the MCT+SR59230A treatment group compared with the MCT-induced PAH group.

Figure 2.

Histological evaluation of right ventricular sections of the PAH rats. Representative images of the right ventricle stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Left, original magnification, ×200; right, original magnification, ×400, magnified images of the boxed areas; bar, 20 µm. Contracture of cardiomyocytes, hypereosinophilia, wavy arrangement of myofibers and cardiomyocyte apoptosis were observed in MCT-induced PAH samples. MCT+SR samples exhibited reduced myocardial disarray. PAH, pulmonary artery hypertension; MCT, monocrotaline; MCT+SR, MCT + SR59230A.

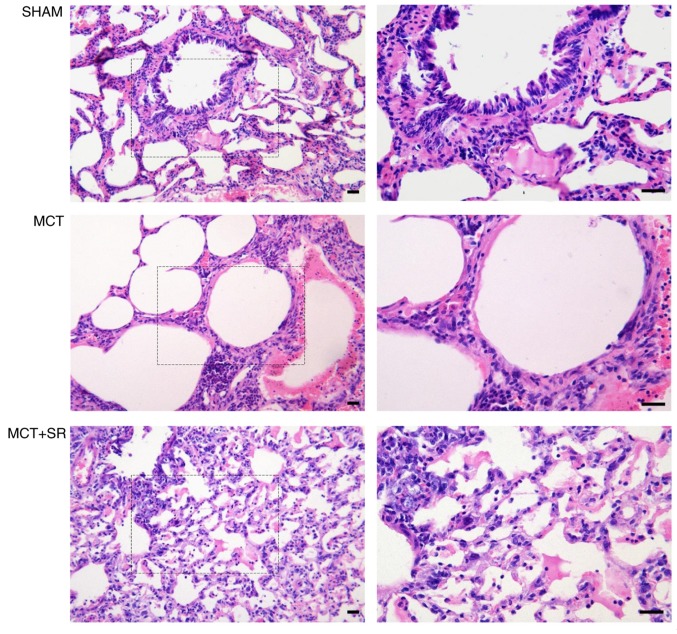

SR59230A reduces MCT-induced alveolar expansion and inflammatory infiltration

Severe pulmonary vascular remodeling was observed in the lung sections of the MCT-induced PAH rats. Compared with the control group, samples from the MCT group exhibited emphysematous expansion of the alveoli, discontinuous endothelium in the pulmonary arterioles, smooth muscle cell hypotrophy and disarrangement, thickening of the vessel wall, a narrowed vascular lumen and dense inflammatory infiltration in a perivascular and peribronchial distribution. Following SR59230A administration, reduced emphysematous expansion of the alveoli and inflammatory infiltration were observed in a perivascular and peribronchial distribution compared with the MCT group. However, MCT-induced pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell hypotrophy and disarrangement did not exhibit obvious improvement following SR59230A treatment (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Histological evaluation of lung sections from PAH rats. Representative images of the left lung stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Left, original magnification, ×200; right, original magnification, ×400, magnified images of the boxed areas; bar, 20 µm. The diameters of the pulmonary alveoli were increased upon MCT administration, with remodeled bronchioles and vessels surrounded by a dense infiltration of inflammatory cells, which were alleviated in the MCT+SR group. PAH, pulmonary artery hypertension; MCT, monocrotaline; MCT+SR, monocrotaline + SR59230A.

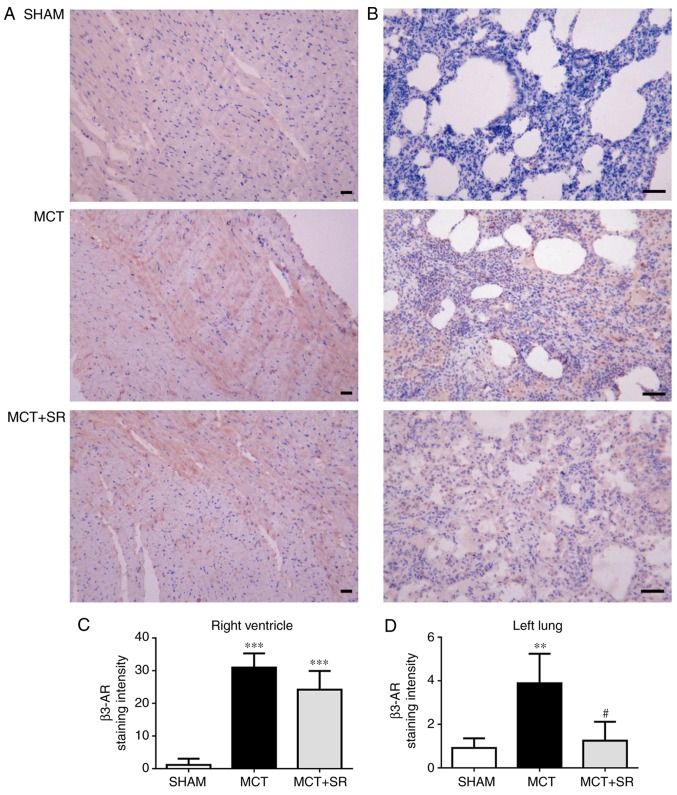

SR59230A suppresses the increase of β3-AR in the lung tissue, but not the RV

To investigate the expression level of β3-AR in the lung and heart tissues, IHC staining of β3-AR was conducted in samples from all three groups. In MCT-induced PAH rats, a significant elevation in β3-AR expression levels was revealed in the RV and lung tissues compared with the sham group (P<0.01). Following 4 weeks of SR59230A treatment, no significant change in β3-AR was observed in the RV (Fig. 4A and C), but a significant reduction was observed in the left lung (P<0.05; Fig. 4B and D).

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical staining of β3-AR visualized by diaminobenzidine (brown) and hematoxylin. Representative images of (A) the right ventricle and (B) the left lung; original magnification, ×200, bar, 20 µm. Staining intensities in (C) the right ventricle and (D) left lung were quantified using FIJI biological-image analysis software. β3-AR, β3-adrenergic receptor; MCT, monocrotaline; MCT+SR, monocrotaline + SR59230A.

SR59230A inhibits eNOS induction in the lung

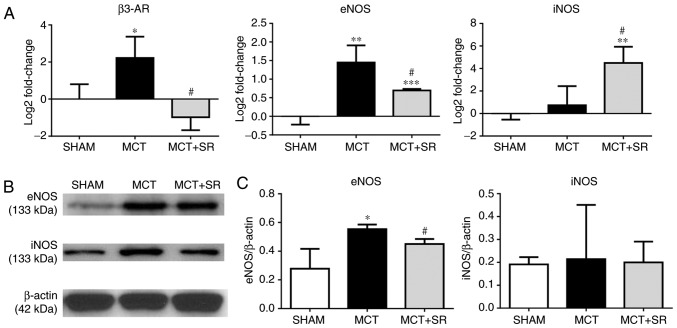

To determine whether β3-AR is involved in regulating the NO signaling pathway in MCT-induced PAH, the expression levels of β3-AR, eNOS and iNOS in the lung were determined. RT-qPCR revealed a significant increase in the expression level of eNOS and an upregulation in β3-AR in the MCT-induced PAH group compared with the sham group (P<0.05), which was consistent with the IHC data. Four weeks of SR59230A treatment significantly reversed the increase in eNOS expression level (P<0.05); though iNOS expression was not significantly altered in the MCT-induced PAH model compared with the sham, there was a significant induction following SR59230A administration (P<0.05; Fig. 5A). At the protein level, western blotting revealed that the eNOS expression level was similarly increased (P<0.05), but to a lesser degree than the change in gene expression (P<0.05). However, no significant change in iNOS expression levels were observed in the SR59230A-treated group (Fig. 5B and C).

Figure 5.

β3-AR, eNOS and iNOS expression levels in the lung tissue. (A) Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction results are presented as log2 fold change values and normalized using β-actin. (B) Representative western blotting images. (C) Western blotting quantification results are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean for each experimental group (N=4). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. MCT and Sham. #P<0.05 vs. MCT group. β3-AR, β3-adrenergic receptor; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; MCT, monocrotaline; MCT+SR, monocrotaline + SR59230A.

Discussion

The present study initially investigated the cardio-protective effects of a β3-AR antagonist in PAH. Treatment with the β3-AR antagonist SR59230A improved RV performance in MCT-induced PAH rats, and alleviated the structural impairment and inflammatory cell infiltration to the RV and lung. Furthermore, the presence of β3-AR in rat lung tissues was confirmed, in addition to the observed overexpression of β3-AR in the RV and lung in PAH. Long-term administration of SR59230A significantly reduced the expression level of β3-AR in the lung compared with the group without SR59230 treatment, but not the RV. Furthermore, the production of eNOS in the PAH lung was associated with changes in the expression level of β3-AR, which was inhibited by SR59230A.

MCT is a pyrrolizidine alkaloid. Its bioactive metabolite causes selective damage to the vascular endothelium of the lung vessels, resulting in an increase in vascular resistance and consequently resulting in high pulmonary arterial pressure (29). The increase in RV-afterload not only induced right ventricular dilation and failure (as indicated by a marked elevation in RV basal diameter, RVWT, E/A ratio and a marked decrease in EF), but also affected the structure and function of the left heart, characterized by reduced LVIDs, LVIDd and LVPWd. In the present study, it was demonstrated that long-term treatment with SR59230A significantly suppressed the MCT-induced increase in RV basal diameter and RVWT. Also, right ventricular EF was recovered and the E/A ratio, a recommended parameter to evaluate RV diastolic function (30), was revealed to approach the normal level following SR59230A therapy. These results contradict previous reports, which revealed the beneficial effects of the β3-AR agonist in a number of pulmonary hypertension models (20,21). These controversies may be partly due to the differences between experimental models; one study used pigs with chronic PH established by the surgical banding of the main pulmonary vein (20), whilst another established a rat PAH model using a lower dose of MCT (60 mg/kg) (21). In addition, it should be noted that the majority of previous studies used non-selective β3-AR agonists; therefore the possibility that the observed beneficial effects may be caused by other β-adrenergic functions (including β2-AR stimulation) should not be excluded (20,22). Conversely, one other study identified the involvement of β1/β2-AR in the development of PAH, and that the α1/β1/β2-AR blocker carvedilol improved RV function and prevented maladaptive myocardial remodeling in rats with severe experimentally-induced PAH. However, concerning side effects, including a large decrease in heart rate, remained (31). Considering that, to the best of our knowledge, no β3-AR antagonist had ever been studied alone in PAH, the present study utilized SR59230A treatment and was the first to reveal the cardio-protective effect of a β3-AR antagonist on an MCT-induced PAH model in vivo.

In contrast to a number of other classical β-AR antagonists, SR59230A has a higher affinity for β3-AR, while it has also been identified to have a similar affinity for other β-ARs (32). By contrast to β1/2AR, β3-AR was revealed to be activated at higher concentrations of catecholamines, and preferentially activated in situations of high adrenergic tone, including chronic heart failure, sepsis and diabetes (33,34). The results revealed an increase in β3-AR expression level in the heart in MCT-induced PAH, though this elevation did not change substantially upon SR59230A treatment. Various reports have indicated that β3-AR antagonists blocked β3-AR activation, therefore preventing the suppression of cardiac contraction and reversing the progression of cardiac dysfunction (35,36). However, only one previous study evaluated the β3-AR expression levels in β3-AR antagonist application (37). In a rat model of isoproterenol-induced heart failure, SR59230A ameliorated cardiac function resulting in reduced β3-AR expression levels. Combined with these results, the results of the present study suggest that the cardio-protective effects of SR59230A in PAH may not be due to its direct effect in controlling the induction of β3-AR in the heart. Alternatively, a higher level of β3-AR expression in PAH may increase the binding affinity of SR59230A, therefore failing to activate the β3-AR response in the heart (38,39). Considering the differences between experimental models, it is necessary to further investigate the association between β3-AR expression levels and β3-adrenergic effects in the heart under PAH conditions. On the other hand, numerous studies have revealed that SR59230A possesses partial or full β3-AR-agonist properties (40,41), but in the present study, no evidence was identified to suggest that SR59230A exhibited β3-AR agonistic, as opposed to antagonistic, properties.

In the present study, SR59230A administration significantly downregulated β3-AR expression levels in the lung compared with the group without SR59230 treatment, but not the heart; this is consistent with the belief that the factors regulating β3-AR vary between species, tissues and diseases stages (4). In addition, the results also revealed that in MCT-induced PAH, alveolar and vascular endothelial damage were accompanied by the overexpression of β3-AR, and that SR59230A treatment inhibited β3-AR expression in the lung, alleviating the expansion of the alveoli and inhibiting inflammatory infiltration to the perivascular and peribronchial area. These results suggest that the increase in β3-AR expression levels in PAH may be responsible for the progressive impairment of alveolar structure and chronic inflammation. Inflammatory infiltration has frequently been observed surrounding remodeled vessels, including plexiform lesions in human PAH (42,43), with an elevated level of pro-inflammatory cytokines including interleukin-6 (IL-6) in circulation and in the lung tissue; specifically, β3-AR stimulation induced IL-6 release from adipocytes (44,45), and β2/3-AR may be responsible for the increase in plasma IL-6 observed during sympathetic activation and in obesity, as opposed to macrophages (46). However, there is currently no evidence to confirm the association between the elevation of IL-6 and the β3 adrenergic responses in experimental models or patients with PAH. Notably, the alleviation of lung remodeling and the reduction of inflammatory infiltration to the pulmonary vasculature following SR59230A therapy may influence RV chronic pressure overload and improve RV function (47,48).

Endothelial-derived NO is a recognized mediator of angiogenesis in pulmonary circulatory vessels. However, the function of NO in regulating pulmonary vascular tone remains unclear (49). Studies have reported that disruption of the eNOS gene and NO administration were associated with altered pulmonary arterial pressure in chronically hypoxic conditions (50,51). Additionally, iNOS deficiency contributed to increased basal pulmonary vascular tone, whereas deficiency of neuronal NOS (nNOS) had no such effect (52). In particular, β3-AR was demonstrated to modulate NO signaling via eNOS, nNOS and iNOS in the heart and vasculature under either pathological conditions or pharmacological stimulation (5,53,54). Furthermore, another study demonstrated that SR59230A inhibited nebivolol-induced NO in isolated heart tissues, suggesting a potential function for β3-AR in regulating iNOS-dependent NO production (54). The dysfunction of eNOS in endothelial cells may indicate an important source for the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in pulmonary hypertension, so-called eNOS uncoupling, which has been observed between β3-AR and eNOS in the failing human myocardium (55,56). In order to investigate the effects of β3-AR antagonism in PAH (via NOS regulation), the expression levels of eNOS and iNOS in the lung were determined in the present study. The results illustrated a marked increase in the eNOS expression level at the transcriptional and translational level in an MCT-induced PAH model compared with the sham group, and a significant decrease in eNOS following SR59230A administration compared with no administration group. The change in eNOS expression level in PAH was consistent with a previous study reporting an increase in eNOS-encoding mRNA in the MCT rat artery (57), but inconsistent with another study reporting no change in MCT-induced PAH (58). These results questioned whether elevated eNOS expression was a compensatory response to satisfy the requirement of NO during PAH, or a sign of oxidative stress (59).

Dissociation between the expression of eNOS and NO was reported in MCT-induced PAH rats (57). Increased ROS, an altered redox state and elevated oxidant stress have been indicated in the lung and RV of various PAH animal models, in addition to MCT toxicity (60). Furthermore, a more recent study revealed that a deficiency in tetrahydrobiopterin, an essential cofactor for eNOS coupling, may be associated with MCT-induced PAH rats (61). In addition, SR59230A may inhibit inflammatory infiltration in the perivascular and peribronchial regions, whereas inflammatory cell recruitment has been known to accelerate the accumulation of ROS and lung functional impairment (62). Therefore, the results of the present study suggested that eNOS induction in PAH may result in the generation of superoxides as opposed to NO. β3-AR antagonists may alleviate progressive lung injury by inhibiting inflammatory infiltration and preventing oxidative stress by regulating the generation of uncoupled eNOS (55).

In addition, no significant change in iNOS was demonstrated in PAH rats compared with the sham control in the present study, which is inconsistent with a previous study in a chronic hypoxia-induced PAH model; this identified a transient induction of iNOS in the pulmonary vascular wall at the initial stages of hypoxia, which returned to more characteristically low levels 20 days later (63). As anticipated, the present study indicated that SR59230A induced a marked increase in the expression level of iNOS mRNA, but not protein. Since changes in gene expression cannot be accounted for by transcription alone, this highlighted that SR59230A itself may be involved in the post-transcriptional or translational regulation of iNOS, which requires further investigation. Additional limitations include the fact that MCT-induced PAH rats may not represent the entire spectrum of PAH models, as only a single time point was observed. However, the present study aimed to evaluate the effect of a β3-AR antagonist on RV function, as the cardio-protective effect of β3-AR agonists and other drug have previously been studied (21,64). RV basal diameter, RVWT, E/A ratio and EF were selected to evaluate RV structure and function under PAH conditions, but due to technical limitations, the pulmonary artery pressure value, Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion and fractional area change values (65) were not obtained. Therefore, it is necessary in future studies to include these parameters. Furthermore, phospho-eNOS and phospho-iNOS antibodies were not included in the western blotting. This may have indicated whether the translocation or phosphorylation of eNOS was involved in the different mechanisms of β3-AR-stimulated eNOS activation, according to the associated anatomical region (66,67). Therefore, further studies evaluating the eNOS activation pathway in the lung are warranted. Last but not least, since only MCT induced PAH models were studied in this manuscript, the effects of β3-AR blockage in other PAH models, for example, in hypoxia rats, remain unknown. Future studies on different PAH models are required to understand the involvement of the β3-AR response in the initiation and development of PAH.

In conclusion, SR59230A, a selective β3-AR antagonist, exerted beneficial effects on RV performance in a rat model of MCT-induced PAH. Also, inhibiting β3-AR with SR59230A may alleviate structural changes and inflammatory infiltration by reducing oxidative stress in the lung.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- β3-AR

β3 adrenergic receptor

- EF

ejection fraction

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- IVSd

interventricular septal end diastole

- LVIDd

left ventricular internal diameter end diastole

- LVIDs

left ventricular internal diameter end systole

- LVPWd

left ventricular posterior wall thickness at end-diastole

- MCT

monocrotaline

- PAH

pulmonary arterial hypertension

- PH

pulmonary hypertension

- RV

right ventricle

- RVWT

right ventricular wall thickness

Funding

The present study was supported by Harbin Medical University (grant no. 2013SYYRCYJ06).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

JS and WL designed the experiment. JS performed research and analyzed the data. XD, JC and JY contributed to the interpretation of the results. JS, JLC and WL wrote the manuscript. The final version of the manuscript has been read and approved by all authors and each author believes that the manuscript represents honest work.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All experimental procedures were ethically approved by the Harbin Medical University Committee on Animal Care and were performed in adherence with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines on the Use of Laboratory Animals.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Xu D, Guo H, Xu X, Lu Z, Fassett J, Hu X, Xu Y, Tang Q, Hu D, Somani A, et al. Exacerbated pulmonary arterial hypertension and right ventricular hypertrophy in animals with loss of function of extracellular superoxide dismutase. Hypertension. 2011;58:303–309. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.166819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Provencher S, Granton JT. Current treatment approaches to pulmonary arterial hypertension. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31:460–477. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2014.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vachiery JL, Gaine S. Challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir Rev. 2012;21:313–320. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00005412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rozec B, Gauthier C. Beta3-adrenoceptors in the cardiovascular system: Putative roles in human pathologies. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;111:652–673. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moens AL, Yang R, Watts VL, Barouch LA. Beta 3-adrenoreceptor regulation of nitric oxide in the cardiovascular system. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:1088–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gauthier C, Tavernier G, Charpentier F, Langin D, Le Marec H. Functional beta3-adrenoceptor in the human heart. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:556–562. doi: 10.1172/JCI118823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niu X, Watts VL, Cingolani OH, Sivakumaran V, Leyton-Mange JS, Ellis CL, Miller KL, Vandegaer K, Bedja D, Gabrielson KL, et al. Cardioprotective effect of beta-3 adrenergic receptor agonism: Role of neuronal nitric oxide synthase. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1979–1987. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.12.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tavernier G, Toumaniantz G, Erfanian M, Heymann MF, Laurent K, Langin D, Gauthier C. Beta3-Adrenergic stimulation produces a decrease of cardiac contractility ex vivo in mice overexpressing the human beta3-adrenergic receptor. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;59:288–296. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(03)00359-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao Q, Zeng F, Liu JB, He Y, Li B, Jiang ZF, Wu TG, Wang LX. Upregulation of β3-adrenergic receptor expression in the atrium of rats with chronic heart failure. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2013;18:133–137. doi: 10.1177/1074248412460123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gauthier C, Langin D, Balligand JL. Beta3-adrenoceptors in the cardiovascular system. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2000;21:426–431. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(00)01562-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhadada SV, Patel BM, Mehta AA, Goyal RK. β(3) Receptors: Role in cardiometabolic disorders. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2011;2:65–79. doi: 10.1177/2042018810390259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rasmussen HH, Figtree GA, Krum H, Bundgaard H. The use of beta3-adrenergic receptor agonists in the treatment of heart failure. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;10:955–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng MG, Prieto MC, Navar LG. Nebivolol-induced vasodilation of renal afferent arterioles involves beta3-adrenergic receptor and nitric oxide synthase activation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;303:F775–F782. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00233.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rozec B, Serpillon S, Toumaniantz G, Sèze C, Rautureau Y, Baron O, Noireaud J, Gauthier C. Characterization of beta3-adrenoceptors in human internal mammary artery and putative involvement in coronary artery bypass management. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:351–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pietri-Rouxel F, Strosberg AD. Pharmacological characteristics and species-related variations of beta 3-adrenergic receptors. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 1995;9:211–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.1995.tb00288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moniotte S, Balligand JL. Potential use of beta(3)-adrenoceptor antagonists in heart failure therapy. Cardiovasc Drug Rev. 2002;20:19–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3466.2002.tb00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pourageaud F, Leblais V, Bellance N, Marthan R, Muller B. Role of beta2-adrenoceptors (beta-AR), but not beta1-, beta3-AR and endothelial nitric oxide, in beta-AR-mediated relaxation of rat intrapulmonary artery. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2005;372:14–23. doi: 10.1007/s00210-005-1082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tagaya E, Tamaoki J, Takemura H, Isono K, Nagai A. Atypical adrenoceptor-mediated relaxation of canine pulmonary artery through a cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent pathway. Lung. 1999;177:321–332. doi: 10.1007/PL00007650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu Y, Fuscoe JC, Zhao C, Guo C, Jia M, Qing T, Bannon DI, Lancashire L, Bao W, Du T, et al. A rat RNA-Seq transcriptomic BodyMap across 11 organs and 4 developmental stages. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3230. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.García-Aívarez A, Pereda D, Garcia-Lunar I, Sanz-Rosa D, Fernández-Jiménez R, García-Prieto J, Nuño-Ayala M, Sierra F, Santiago E, Sandoval E, et al. Beta-3 adrenergic agonists reduce pulmonary vascular resistance and improve right ventricular performance in a porcine model of chronic pulmonary hypertension. Basic Res Cardiol. 2016;111:49. doi: 10.1007/s00395-016-0567-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perros F, Ranchoux B, Izikki M, Bentebbal S, Happé C, Antigny F, Jourdon P, Dorfmüller P, Lecerf F, Fadel E, et al. Nebivolol for improving endothelial dysfunction, pulmonary vascular remodeling and right heart function in pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:668–680. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pott C, Brixius K, Bundkirchen A, Bölck B, Bloch W, Steinritz D, Mehlhorn U, Schwinger RH. The preferential beta3-adrenoceptor agonist BRL 37344 increases force via beta1-/beta2-adrenoceptors and induces endothelial nitric oxide synthase via beta3-adrenoceptors in human atrial myocardium. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;138:521–529. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hicks A, McCafferty GP, Riedel E, Aiyar N, Pullen M, Evans C, Luce TD, Coatney RW, Rivera GC, Westfall TD, Hieble JP. GW427353 (solabegron), a novel, selective beta3-adrenergic receptor agonist, evokes bladder relaxation and increases micturition reflex threshold in the dog. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;323:202–209. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.125757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pankey EA, Edward JA, Swan KW, Bourgeois CR, Bartow MJ, Yoo D, Peak TA, Song BM, Chan RA, Murthy SN, et al. Nebivolol has a beneficial effect in monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2016;94:758–768. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2015-0431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gan RT, Li WM, Wang X, Wu S, Kong YH. Effect of beta3-adrenoceptor antagonist on the cardiac function and expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in a rat model of heart failure. Zhongguo Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2007;19:675–678. (In Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Y, Li Z, Zhang Y, Yang W, Sun J, Shan L, Li W. Targeting Pin1 protects mouse cardiomyocytes from high-dose alcohol-induced apoptosis. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:4528906. doi: 10.1155/2016/4528906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Washington (DC): 2011. th (ed) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schultze AE, Roth RA. Chronic pulmonary hypertension-the monocrotaline model and involvement of the hemostatic system. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 1998;1:271–346. doi: 10.1080/10937409809524557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rudski LG, Lai WW, Afilalo J, Hua L, Handschumacher MD, Chandrasekaran K, Solomon SD, Louie EK, Schiller NB. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: A report from the American Society of Echocardiography endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23:685-713–quiz 786–788. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bogaard HJ, Natarajan R, Mizuno S, Abbate A, Chang PJ, Chau VQ, Hoke NN, Kraskauskas D, Kasper M, Salloum FN, Voelkel NF. Adrenergic receptor blockade reverses right heart remodeling and dysfunction in pulmonary hypertensive rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:652–660. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201003-0335OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baker JG, Hill SJ, Summers RJ. Evolution of β-blockers: From anti-anginal drugs to ligand-directed signalling. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2011;32:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dessy C, Balligand JL. Beta3-adrenergic receptors in cardiac and vascular tissues emerging concepts and therapeutic perspectives. Adv Pharmacol. 2010;59:135–163. doi: 10.1016/S1054-3589(10)59005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strosberg AD. Structure and function of the beta 3-adrenergic receptor. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;37:421–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng HJ, Zhang ZS, Onishi K, Ukai T, Sane DC, Cheng CP. Upregulation of functional beta(3)-adrenergic receptor in the failing canine myocardium. Circ Res. 2001;89:599–606. doi: 10.1161/hh1901.098042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morimoto A, Hasegawa H, Cheng HJ, Little WC, Cheng CP. Endogenous beta3-adrenoreceptor activation contributes to left ventricular and cardiomyocyte dysfunction in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H2425–H2433. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01045.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gan RT, Li WM, Xiu CH, Shen JX, Wang X, Wu S, Kong YH. Chronic blocking of beta 3-adrenoceptor ameliorates cardiac function in rat model of heart failure. Chin Med J (Engl) 2007;120:2250–2255. doi: 10.1097/00029330-200712020-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ursino MG, Vasina V, Raschi E, Crema F, De Ponti F. The beta3-adrenoceptor as a therapeutic target: Current perspectives. Pharmacol Res. 2009;59:221–234. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hutchinson DS, Chernogubova E, Sato M, Summers RJ, Bengtsson T. Agonist effects of zinterol at the mouse and human beta(3)-adrenoceptor. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2006;373:158–168. doi: 10.1007/s00210-006-0056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sato M, Horinouchi T, Hutchinson DS, Evans BA, Summers RJ. Ligand-directed signaling at the beta3-adrenoceptor produced by 3-(2-Ethylphenoxy)-1-[(1,S)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronapt-1-ylamino]-2S-2-propanol oxalate (SR59230A) relative to receptor agonists. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:1359–1368. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.035337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vrydag W, Michel MC. Tools to study beta3-adrenoceptors. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2007;374:385–398. doi: 10.1007/s00210-006-0127-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Price LC, Wort SJ, Perros F, Dorfmüller P, Huertas A, Montani D, Cohen-Kaminsky S, Humbert M. Inflammation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest. 2012;141:210–221. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steiner MK, Syrkina OL, Kolliputi N, Mark EJ, Hales CA, Waxman AB. Interleukin-6 overexpression induces pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res. 2009;104:236–244. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mottillo EP, Shen XJ, Granneman JG. Beta3-adrenergic receptor induction of adipocyte inflammation requires lipolytic activation of stress kinases p38 and JNK. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801:1048–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tchivileva IE, Tan KS, Gambarian M, Nackley AG, Medvedev AV, Romanov S, Flood PM, Maixner W, Makarov SS, Diatchenko L. Signaling pathways mediating beta3-adrenergic receptor-induced production of interleukin-6 in adipocytes. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:2256–2266. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mohamed-Ali V, Flower L, Sethi J, Hotamisligil G, Gray R, Humphries SE, York DA, Pinkney J. Beta-adrenergic regulation of IL-6 release from adipose tissue: In vivo and in vitro studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:5864–5869. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.12.8104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haddad F, Doyle R, Murphy DJ, Hunt SA. Right ventricular function in cardiovascular disease, part II: Pathophysiology, clinical importance and management of right ventricular failure. Circulation. 2008;117:1717–1731. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.653584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sydykov A, Mamazhakypov A, Petrovic A, Kosanovic D, Sarybaev AS, Weissmann N, Ghofrani HA, Schermuly RT. Inflammatory mediators drive adverse right ventricular remodeling and dysfunction and serve as potential biomarkers. Front Physiol. 2018;9:609. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klinger JR, Abman SH, Gladwin MT. Nitric oxide deficiency and endothelial dysfunction in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:639–646. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201304-0686PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roberts JD, Jr, Roberts CT, Jones RC, Zapol WM, Bloch KD. Continuous nitric oxide inhalation reduces pulmonary arterial structural changes, right ventricular hypertrophy and growth retardation in the hypoxic newborn rat. Circ Res. 1995;76:215–222. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.76.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Steudel W, Ichinose F, Huang PL, Hurford WE, Jones RC, Bevan JA, Fishman MC, Zapol WM. Pulmonary vasoconstriction and hypertension in mice with targeted disruption of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (NOS 3) gene. Circ Res. 1997;81:34–41. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.81.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fagan KA, Tyler RC, Sato K, Fouty BW, Morris KG, Jr, Huang PL, McMurtry IF, Rodman DM. Relative contributions of endothelial, inducible and neuronal NOS to tone in the murine pulmonary circulation. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:L472–L478. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.277.3.L472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Amour J, Loyer X, Le Guen M, Mabrouk N, David JS, Camors E, Carusio N, Vivien B, Andriantsitohaina R, Heymes C, Riou B. Altered contractile response due to increased beta3-adrenoceptor stimulation in diabetic cardiomyopathy: The role of nitric oxide synthase 1-derived nitric oxide. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:452–460. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000278909.40408.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maffei A, Di Pardo A, Carangi R, Carullo P, Poulet R, Gentile MT, Vecchione C, Lembo G. Nebivolol induces nitric oxide release in the heart through inducible nitric oxide synthase activation. Hypertension. 2007;50:652–656. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.094458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.d'Uscio LV. eNOS uncoupling in pulmonary hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;92:359–360. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Napp A, Brixius K, Pott C, Ziskoven C, Boelck B, Mehlhorn U, Schwinger RH, Bloch W. Effects of the beta3-adrenergic agonist BRL 37344 on endothelial nitric oxide synthase phosphorylation and force of contraction in human failing myocardium. J Card Fail. 2009;15:57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nakazawa H, Hori M, Ozaki H, Karaki H. Mechanisms underlying the impairment of endothelium-dependent relaxation in the pulmonary artery of monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertensive rats. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;128:1098–1104. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seta F, Rahmani M, Turner PV, Funk CD. Pulmonary oxidative stress is increased in cyclooxygenase-2 knockdown mice with mild pulmonary hypertension induced by monocrotaline. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Karbach S, Wenzel P, Waisman A, Munzel T, Daiber A. eNOS uncoupling in cardiovascular diseases-the role of oxidative stress and inflammation. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20:3579–3594. doi: 10.2174/13816128113196660748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Demarco VG, Whaley-Connell AT, Sowers JR, Habibi J, Dellsperger KC. Contribution of oxidative stress to pulmonary arterial hypertension. World J Cardiol. 2010;2:316–324. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v2.i10.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Francis BN, Salameh M, Khamisy-Farah R, Farah R. Tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4): Targeting endothelial nitric oxide synthase as a potential therapy for pulmonary hypertension. Cardiovasc Ther. 2018;36 doi: 10.1111/1755-5922.12312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dorfmüller P, Chaumais MC, Giannakouli M, Durand-Gasselin I, Raymond N, Fadel E, Mercier O, Charlotte F, Montani D, Simonneau G, et al. Increased oxidative stress and severe arterial remodeling induced by permanent high-flow challenge in experimental pulmonary hypertension. Respir Res. 2011;12:119. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hampl V, BíbovBbová J, BanasovBbová A, Uhlík J, Miková D, Hnilicková O, Lachmanová V, Herget J. Pulmonary vascular iNOS induction participates in the onset of chronic hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L11–L20. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00023.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang Y, Tian W, Xiu C, Yan M, Wang S, Mei Y. Urantide improves the structure and function of right ventricle as determined by echocardiography in monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension rat model. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;38:29–35. doi: 10.1007/s10067-018-3978-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kimura K, Daimon M, Morita H, Kawata T, Nakao T, Okano T, Lee SL, Takenaka K, Nagai R, Yatomi Y, Komuro I. Evaluation of right ventricle by speckle tracking and conventional echocardiography in rats with right ventricular heart failure. Int Heart J. 2015;56:349–353. doi: 10.1536/ihj.14-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brixius K, Bloch W, Pott C, Napp A, Krahwinkel A, Ziskoven C, Koriller M, Mehlhorn U, Hescheler J, Fleischmann B, Schwinger RH. Mechanisms of beta 3-adrenoceptor-induced eNOS activation in right atrial and left ventricular human myocardium. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;143:1014–1022. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brixius K, Bloch W, Ziskoven C, Bölck B, Napp A, Pott C, Steinritz D, Jiminez M, Addicks K, Giacobino JP, Schwinger RH. Beta3-adrenergic eNOS stimulation in left ventricular murine myocardium. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006;84:1051–1060. doi: 10.1139/y06-033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.