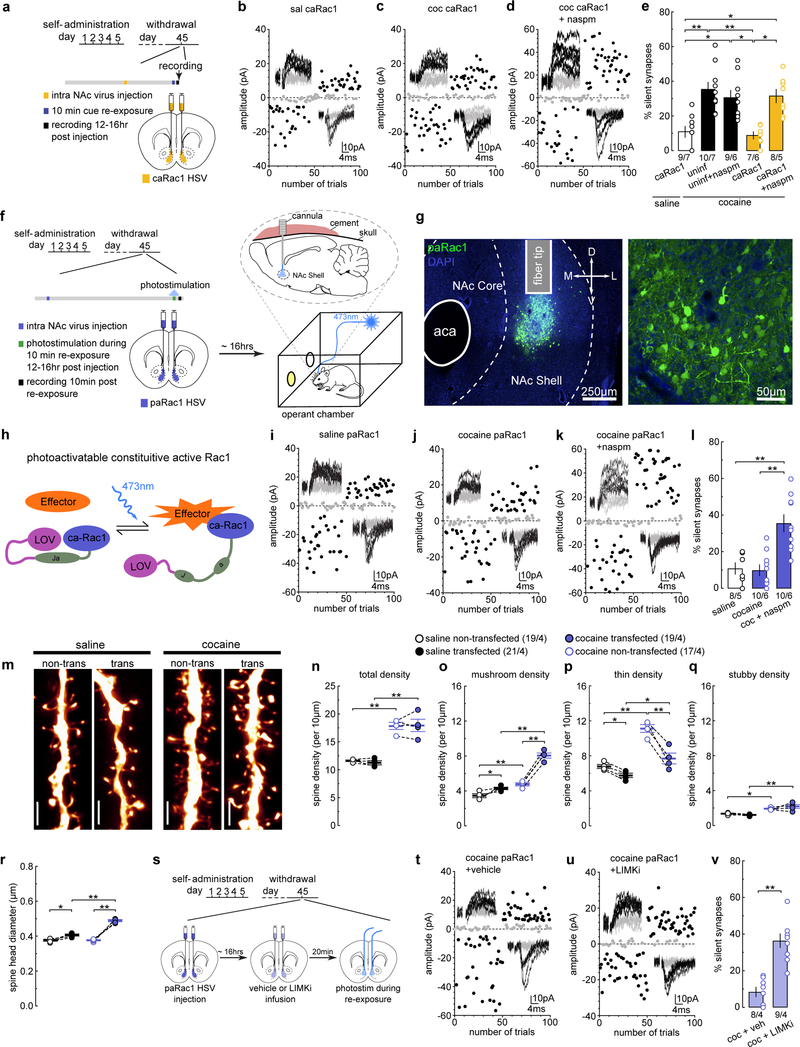

Figure 5. Increasing Rac1 activity prevents cue-induced synaptic re-silencing.

(a) Diagram showing the experimental timeline.

(b-d) Example EPSCs evoked at −70mV and +50mV during the minimal stimulation assay (insets) over 100 trials from example caRac1-expressing MSNs in saline- (b), and cocaine-trained rats (c), and the effects of naspm (d).

(e) Summary showing that caRac1 expression prevented the cue re-exposure-induced increase in the % silent synapses in cocaine-trained rats after 45 days of withdrawal from self-administration, while perfusion of naspm restored this % to high levels (saline caRac1 = 10.34 ± 2.90, n = 7 animals; cocaine non-trans = 37.22 ± 5.40, n = 7 animals; cocaine non-trans naspm = 27.94 ± 4.94, n = 6 animals; cocaine caRac1 = 8.49 ± 2.10, n =6 animals; cocaine caRac1 naspm = 30.76 ± 3.17, n = 5 animals, F4,26=10.44, p<0.0001, one-way ANOVA; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, Bonferroni posttest).

(f) Diagrams showing the experimental design, in which NAcSh pa-Rac1 was photoactivated during the 10 min cue re-exposure in rats on withdrawal day 45.

(g) Example images of a NAcSh slice (left) and MSNs (right) showing HSV-mediated expression of paRac1. All animals used in Fig 5l, Fig 5n-r, Fig 5v, and Fig 6q (n = 41 animals) had pa-dnRac1 expression localized within the NAcSh.

(h) Diagram illustrating the design concept of paRac1.

(i-k) EPSCs evoked at −70mV and +50mV during the minimal stimulation assay (insets) over 100 trials from example paRac1-expressing MSNs in saline- (i) and cocaine-trianed rats (j), and the effects of naspm (k).

(l) Summary showing that stimulating paRac1 during cue re-exposure prevented cue re-exposure-induced re-silencing of the matured silent synapses in cocaine-trained rats, which was revealed by perfusion of naspm; paRac1 stimulation did not affect the % silent synapses in saline-trained rats (saline = 12.32 ± 2.74, n = 5 animals; cocaine = 9.39 ± 2.81, n = 6 animals; cocaine naspm = 34.83 ± 5.09, n = 6 animals, F2,14=13.74, p=0.0005, one-way ANOVA; **p<0.01, Bonferroni posttest).

(m) Example NAcSh dendrites of MSNs without and without paRac1 expression from saline-trained rats and cocaine-trained rats with photostimulation during cue re-exposure. Scale bar, 2.5 μm.

(n) Summary showing that the total spine density was increased in cocaine-trained rats after cue re-exposure for both non-transduced and transduced MSNs compared to saline-trained rats (saline non-trans = 11.62 ± 0.138, n = 4 animals; saline trans = 11.23 ± 0.363, n = 4 animals; cocaine non-trans = 17.83 ± 0.631, n = 4 animals; cocaine trans = 17.94 ± 1.11, n =4 animals, F1,6=55.47, p=0.0003, RM two-way ANOVA, drug main effect; **p<0.01, Bonferroni posttest).

(o) Summary showing the increased density of mushroom-like spines was preserved in pcRac1-expressing MSNs from cocaine-trained rats after cue re-exposure, while the density in non-transduced MSNs decreased. paRac1 stimulation also led to a small, but significant increase in mushroom-like spine density in saline-trained rats (saline non-trans = 3.46 ± 0.216, n = 4 animals; saline trans = 4.28 ± 0.140, n = 4 animals; cocaine non-trans = 4.77 ± 0.175, n = 4 animals; cocaine trans = 8.04 ± 0.295, n =4 animals, F1,6=57.03, p=0.0003, RM two-way ANOVA, drug x transduced interaction; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, Bonferroni posttest).

(p) Summary showing the decreased density of thin spines was preserved in paRac1-expressing MSNs from cocaine-trained rats after cue re-exposure, while the density in non-transduced MSNs increased. paRac1 stimulation also led to a small, but significant decrease in thin spine density in saline-trained rats (saline non-trans = 6.80 ± 0.230, n = 4 animals; saline trans = 5.76 ± 0.253, n = 4 animals; cocaine non-trans = 11.12 ± 0.439, n = 4 animals; cocaine trans = 7.70 ± 0.618, n =4 animals, F1,6=30.88, p=0.0014, RM two-way ANOVA, drug x transduced interaction; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, Bonferroni posttest).

(q) Summary showing the density of stubby spines is increased in cocaine-trained rats after cue re-exposure for both non-transduced and transduced MSNs compared to saline-trained rats (saline non-trans = 1.37 ± 0.060, n = 4 animals; saline trans = 1.22 ± 0.050, n = 4 animals; cocaine non-trans = 1.95 ± 0.070, n = 4 animals; cocaine trans = 2.20 ± 0.225, n =4 animals, F1,6=35.71, p=0.0010, RM two-way ANOVA, drug main effect; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, Bonferroni posttest).

(r) Summary showing the increased mean spine head diameter was preserved in paRac1-expressing MSNs from cocaine-trained rats after cue re-exposure, while the density in non-transduced MSNs normalized back to saline control levels. paRac1 stimulation also led to a small, but significant increase in spine head diameter in saline-trained rats (saline non-trans = 0.375 ± 0.005, n = 4 animals; saline trans = 0.405 ± 0.006, n = 4 animals; cocaine non-trans = 0.377 ± 0.004, n = 4 animals; cocaine trans = 0.488 ± 0.006, n =4 animals, F1,6=37.43, p=0.0009, RM two-way ANOVA, drug x transduced interaction; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, Bonferroni posttest).

(s) Diagram showing the experimental timeline for LIMKi experiments.

(t,u) EPSCs evoked at −70mV and +50mV during the minimal stimulation assay (insets) over 100 trials from example paRac1-expressing MSNs from cocaine-trained rats with photostimulation during cue re-exposure with pretreatment of vehicle (t) or LIMKi (u).

(v) Summary showing that pretreatment of LIMKi prevented the effect of paRac1 stimulation on preserving cocaine-generated synapses against re-silencing, such that the % silent synapses were increased compared to vehicle-treated rats (cocaine vehicle = 8.55 ± 1.59, n = 4 animals; cocaine LIMKi = 41.73 ± 6.34, n = 4 animals, t6=5.08, p=0.0023, two-sided unpaired t-test). See Supplemental Table 1 for exact p values for all comparisons made during posthoc tests. Data presented as mean±SEM.