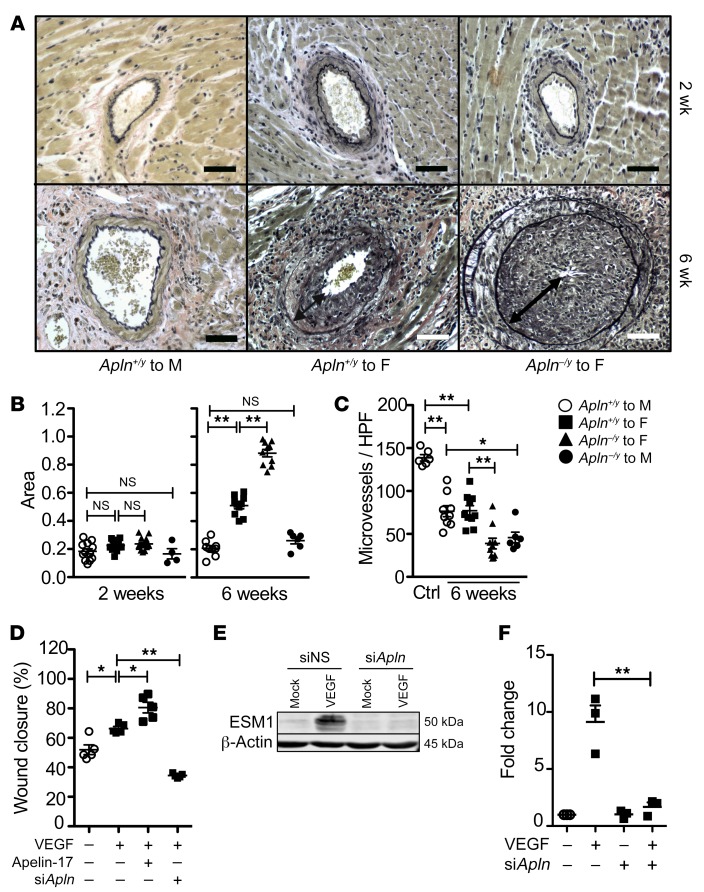

Figure 2. Apelin loss exacerbates arterial vasculopathy and blunts endothelial repair.

(A) Photomicrographs of coronary arteries from mouse heart transplants, with van Gieson stain to highlight the internal elastic lamina in black. Syngeneic male-to-male transplants have a single-cell layer of intima. Progressive expansion of the intima is evident from 2 weeks (top panels) to 6 weeks (bottom panels) after transplantation in allogeneic male to apelin WT female transplants, which is more marked among apelin-deficient male donor hearts. Scale bars: 50 μm. (B) Quantitation of intima area as a fraction of the area within the internal elastic lamina at 2 weeks and 6 weeks after transplantation among grafts as in Figure 1. (C) Microvessel density among freshly harvested donor reference hearts versus WT or apelin-deficient hearts from B recovered 6 weeks after transplantation. Mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. (D) ECs were transfected with scrambled or apelin siRNA, then plated at confluence. The monolayers were injured with a scratch wound, then stimulated with VEGF (50 ng/mL) or apelin-17 analog (1 μM) as indicated (n = 5 biological replicates in independent experiments). Mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. (E) ECs were transfected with scrambled or apelin siRNA, then plated at confluence. The monolayers were injured with multiple scratch wounds, then stimulated with VEGF (50 ng/mL) or mock-treated. Western immunoblot of EC lysates for ESM1. Representative of 3 biological replicates. (F) Quantitation of data in E (n = 3 biological replicates). Mean ± SEM; **P < 0.01 by 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test.