Abstract

Background

Aluminum a known neuro and cholinotoxin has been implicated in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Its exposure is associated with impairment of the memory and cognition.

Objective

The present study was undertaken to evaluate the anti-Alzheimer’s activity of Vitis vinifera in aluminum induced Alzheimer’s disease.

Materials and methods

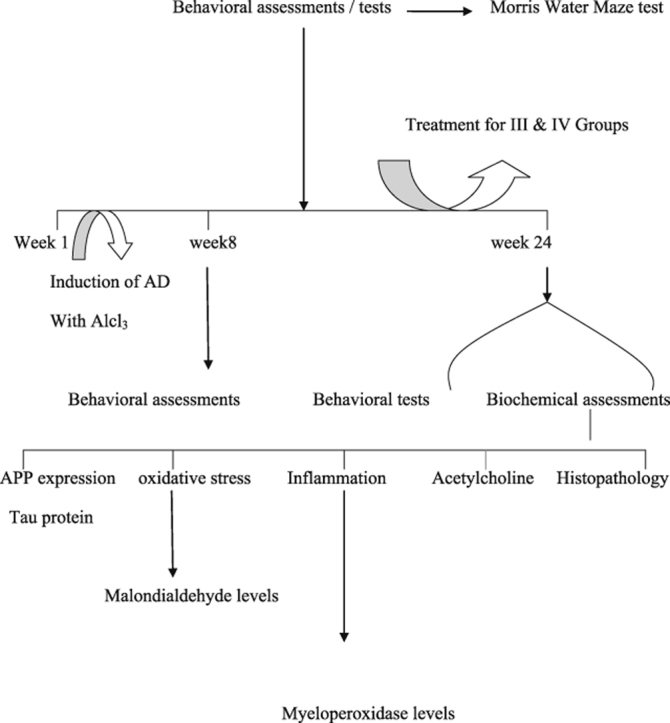

In this study, we investigated the behavioral and biochemical effects of aluminum in Sprague-Dawley rats. Animals were exposed to aluminum chloride (100 mg/kg/day) orally for a period of 8 weeks. Vitis was given in doses of 250 mg/kg and 500 mg/kg for 16 weeks and the possible effects of Vitis vinifera on the expression of Tau and amyloid precursor protein were evaluated by PCR analysis and the possible activities of lipid peroxidation, inflammation and anti-cholinesterase activity were evaluated.

Results

Aluminum intoxication was associated with significant impairment in learning and memory in Morris water maze test. A significant improvement was observed with Vitis vinifera in a dose dependent manner.

Conclusion

The findings of the present study revealed the significant neuroprotective actions of Vitis vinifera by modifying the biochemical parameters and inhibited the mRNA expression of Amyloid Precursor Protein and Tau, which are the key pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease, which was further confirmed by histopathological observations.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Tau, Amyloid Precursor Protein, Vitis vinifera

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD), is the most common form of dementia, in the class of neurodegenerative disorders that leads to progressive loss of memory. The disease exists in two main forms: familial AD affects people younger than 65, while the remainder is sporadic form that can be seen in adults aged 65 and older. The prevalence of AD varies between many different factors, including age, co-morbidities, genetics, diseases, and education level. It is not possible to diagnose AD without performing autopsy; also there is no cure for AD as the currently available drugs for AD only treat the symptoms and do not mitigate the underlying pathogenic mechanisms of the disease.

AD is characterized by the presence of β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and loss of neurons. Presence of amyloid plaques and tangles are the two major pathological hallmarks of the disease. However, in recent years, several approaches aimed at inhibiting disease progression have advanced to clinical trials. Aluminum (Al), a non-essential element is a common constituent in household utensils, medicines and drinking water [1]. It is the third most abundant element in the earth's crust and its exposure is known to be involved in the development of AD [2].

Al, which can gain easy access into the body, is reported to cause alteration of blood brain barrier [3]; under normal physiological conditions it accumulates in the neurons of different regions of the brain and causes apoptotic loss of neurons. It also potentiates the damage of antioxidant system in the body. Chronic exposure of Al induces oxidative stress and damages the CA1 and CA3 field of hippocampus [4]. It may also induce aging as it promotes oxidative stress.

Al also promotes the accumulation of β-amyloid protein and Tau aggregation. Amyloid plaques contain Aβ peptide and the Aβ deposition is the central and fundamental cause of AD [5]. It is a product obtained by the sequential cleavage of a transmembrane glycoprotein called the Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP), by β and γ secretases [6], [7]. Hence, it is mainly referred to as a neurotoxin and apart from it, Al also disturbs the cholinergic system by structural modification of the nicotinic receptors leading to memory loss and hence acting as a potent cholinotoxin [8]. Even though the toxicity of Al in AD pathogenesis is in debate, the physiological alterations produced by this element are toxic and are similar to the symptoms of the AD.

AD involves multiple pathologies; the presently available drugs for the treatment of AD are symptomatic only and do not alter the course or progression of the underlying disease and also produce adverse reactions in patients thereby, having limited scope for the treatment of AD. Thus, there is an urgent need to develop targeted effective therapeutics for the treatment of AD which may alter the course or progression of the underlying disease by treating the disease. Researchers are also looking for alternative treatments for this disease, as the disease treatment targets multiple mechanisms such as formation of amyloid plaques and Tau tangles, anti-inflammatory actions, antioxidant, anti-cholinergic, dopaminergic, serotonergic and calcium blockers etc.

Even though the causes for AD are multiple, oxidative stress takes lead as the main trigger for AD leading to increased levels of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and decreased energy supplement in brain [9]. Hence antioxidants play a major role in AD.

The eventual aim of AD therapy is to stop or slow down the progress of the disease. Several therapeutic strategies have been developed to treat AD, such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-amyloid and anti-cholinergic approaches. Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine have a modest clinical effect on the symptoms. These drugs do not prevent the deterioration of dementia. Finding an effective method to treat AD still poses a significant clinical challenge.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

Young male Sprague–Dawley rats (15 weeks old) weighing 250–300 g procured from NIN laboratories Hyderabad were used for the study. Rats were housed in polyacrylic cages (38 × 23 × 10 cm) with not more than 5 animals per cage. They were housed under standard (25 ± 2 °C, 60–70% humidity) laboratory conditions on normal dark and light cycle. Standard rat chow pellets (NIN rat feed, Hyderabad) and water was allowed ad libitum. Animals were acclimatized to standard laboratory conditions before the experiments. All behavioral experiments were carried out between 10.00 am and 5.00 pm. The experiments were carried out according to the guidelines of the “Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals” (CPCSEA) (Regd. No. 516/01/ACPCSEA), New Delhi, India and approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC), Andhra University, Visakhapatnam.

2.1.1. Materials

Vitis vinifera fruits were purchased from local fruit market in Visakhapatnam, India. They were shade dried, blended and sieved to obtain a fine powder. This was tested for acute and sub-acute toxicity studies and found to be non-toxic.

2.2. Chemicals

Aluminum chloride (AlCl3) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich Hyderabad; primers sequences obtained from Shanghai Sangon Biotech; RT-PCR kits by Promega, USA and Trizol reagent from Invitrogen, Germany.

2.3. Grouping and treatment schedule

Animals were divided into 4 groups (n = 10) and assigned as follows

| S. No. | Group | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | I. Control | Control animals treated with vehicle (drinking water). |

| 2. | II. Diseased control (100 mg/kg) | Rats induced with AlCl3 orally for 8 + 16 weeks. |

| 3. | III. Treatment | Rats induced with AlCl3 for 8 weeks and treated with Vitis 250 mg/kg for 16 weeks. |

| 4. | IV. Treatment | Rats induced with AlCl3 for 8 weeks and treated with Vitis 500 mg/kg for 16 weeks. |

All the animals except the control (group I) were administered with AlCl3 orally at a dose of 100 mg/kg for 8 weeks to set up the AD animal model. Animals were subjected to behavioral tests before the start of the experiment. After 8 weeks of the AlCl3 treatment, significant memory lapses were observed at 8 weeks which confirmed the onset of Alzheimer's like symptoms. After 8 weeks of AlCl3 administration, the treatment with V. vinifera 250 mg/kg and 500 mg/kg was started for groups III and IV and continued for a period of 16 weeks. Treatment with AlCl3 was continued during this period.

After 16 weeks of respective treatment, animals were subjected to Morris water maze test, subsequent to which the animals were sacrificed and the brains were harvested. A 10% brain homogenate was prepared and various biochemical estimations were performed.

2.4. Behavioral assessments

2.4.1. Assessment of cognitive performance

Morris water maze (MWM) test: Animals were tested in a spatial version of Morris water maze test [10]. The maze consisted of circular pool (1.2 m in diameter and 0.47 m high) made of iron. The pool was filled to a depth of 20 cm with water (25 °C) and milk was added to make the medium opaque. An escape platform made up of iron was submerged 0.5 cm under the water level. The animal had to swim until it found the hidden platform. The MWM task was carried out for five consecutive days starting from day one. The animals received four consecutive daily training trials with each trial having a ceiling time of 90 s and a trial interval of approximately 40 s. For each trial rats were put into the water at one of the four starting positions, the sequence of which is selected randomly. During test, trial animals were placed into the tank at the same starting point, with their heads facing the wall. The rat had to swim until it reached onto the platform submerged in the water. After climbing on to the platform, the animal remained there for 20 s before the commencement of next trial. If the animal failed to reach the escape platform within the maximally allowed time of 90 s, it was gently placed on the platform to remain there for the same amount of time. On the fifth day, time taken to reach the platform (escape latency/latency period in seconds) was measured.

2.5. Biochemical and molecular assessments

Biochemical and molecular tests were conducted 24 h after the last behavioral test.

2.5.1. Brain homogenate preparation

The animals were decapitated under ether anesthesia. The skull was cut open and the brain was exposed from its dorsal side. The whole brain was quickly removed and cleaned with chilled normal saline on ice. A 10% (w/v) homogenate of brain samples (0.03 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) was prepared by using polytron homogenizer. The homogenized tissue was used to measure the various biochemical parameters.

2.5.2. Estimation of Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP) and Tau by RT-PCR analysis

RT-PCR analysis of selected genes for AD: cDNA was amplified in 20 μl reaction volume containing PCR master mix with specific primers for Tau, APP (Amyloid Precursor Protein) and β-actin using Taq polymerase. The PCR mixture was amplified in DNA thermal cycler through 35 cycles for all the genes at different specifications. PCR products were detected by electrophoresis on agarose gel (1.5%) containing ethidium bromide.

The resultant cDNA were amplified separately. Amplification and detection were performed with CFX96 Real Time PCR system (BioRad) using emission from SYBR Green. After the initial activation step PCR at 50 °C for 2 min and hot start at 95 °C for 10 min. PCR cycle consisted of 40 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s, and 62 °C for 60 s and 55.7 °C for 60 s for APP, Tau and β-actin. Specificity of qPCR was assessed by performing a dissociation curve. Gene expression was normalized with the mean of β-actin content and calculated relative to controls using standard curve method. Results were finally expressed as CT threshold cycle.

Primer sequences for estimation of the markers are as follows:

| Gene | Primer sequence |

|---|---|

| β-actin | Forward – 5′-TTCTGTCTACTGAACTTCGGGTGATCGGTCC-3′ |

| Reverse – 5′-TATGAGATAGCAAATCGGCTGACGGTGTGGG-3′ | |

| Tau | Forward – 5′-AAGACAGACCATGGAGCAGAAATC-3′ |

| Reverse – 5′-CGGCTAACGTGGCAAGCT-3′ | |

| APP | Forward – 5′-TCGGACATGATTCAGGATTT-3′ |

| Reverse – 5′-TGATGACAATCACGGTTGCTA-3′ |

2.5.3. Measurement of oxidative stress

2.5.3.1. Estimation of lipid peroxidation

MDA levels in brain homogenate were measured by the method developed by Ref. [11]. To the sample of 0.2 ml of tissue homogenate, 0.2 ml of 9.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1.5 ml of 0.9% aqueous solution of Thiobarbituric acid (TBA) were added. The mixture was made up to 5 ml with distilled water and then heated in an oil bath at 95 °C for 60 min using a condenser. After cooling with tap water, 5 ml of mixture of n-butanol and pyridine (15:1 v/v) was added and shaken vigorously. After centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 10 min, the organic layer was taken and its absorbance was measured at 532 nm. The tissue MDA levels were measured from the standard curve and expressed as nmol/g tissue.

2.5.4. Measurement of inflammation

2.5.4.1. Myeloperoxidase (MPO) assay

The activity of myeloperoxidase was assessed using the method modified from that of Mullane [12]. After freeze-thawing for three times the 10% w/v homogenate samples were centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C and the resulting supernatant was assayed spectrophotometrically for MPO. 960 μl of phosphate buffer containing O-diansidine dihydrochloride and hydrogen peroxide was added to 40 μl of the sample and mixed and shaken vigorously. The change in the absorbance of this mixture was measured at 460 nm for 3 min at an interval of 60 s. One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of MPO that causes a change in absorbance measured at 460 nm for 3 min. Myeloperoxidase activity was expressed as units/g of tissue.

2.5.5. Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) assay

Cholinergic dysfunction was assessed in terms of acetylcholinesterase activity. The quantitative measurement of AChE levels in brain was performed according to the method of Ellman [13]. The assay mixture contained 0.05 ml of supernatant, 3 ml of 0.01 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8), 0.10 ml of acetylthiocholine iodide and 0.10 ml of 5,5′ dithiobis-(2-nitro benzoic acid) (Ellman reagent). The change in absorbance was measured at 412 nm for 5 min. Results were calculated using molar extinction co-efficient of chromophore (1.36 × 104 M−1 cm−1) and expressed as percentage control.

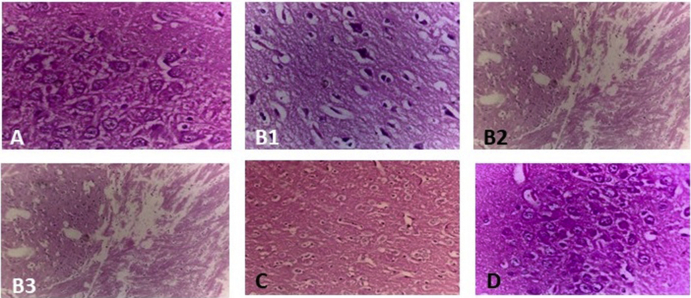

2.6. Histopathological analysis

Animals were sacrificed and brains were harvested. The intact whole brain was transferred to formalin (10% v/v). The tissue was cut into 3 mm thickness and its blocks were embedded in paraffin. The brain sections of 5–10 μm, thick were prepared, stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed according to the standard protocol [14].

2.7. Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed via one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni post hoc test using SPSS 10 software. Data presented are mean ± SEM (n = 10). A value of p ≤ 0.05 was considered as significant.

3. Results

The present study was carried out to investigate the protective effect of V. vinifera in AlCl3 induced biochemical and behavioral alterations in Sprague–Dawley rats. Further, changes in brain histopathology were also examined. PCR studies were also carried out (see Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5).

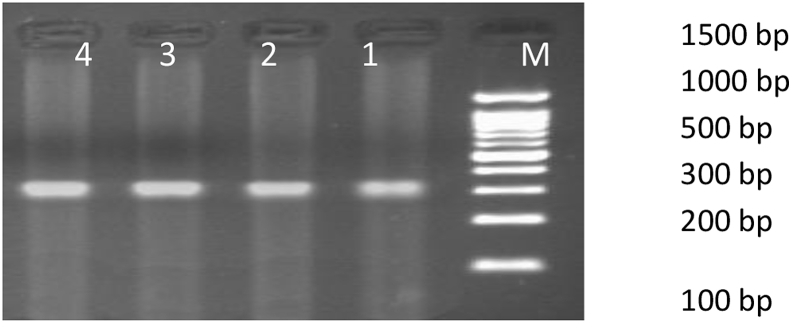

Fig. 1.

Figure showing 352 bp PCR amplification product of β-Actin gene. Lane 1–4: sample number 1–4; Lane M: 100 bp Maker. 1. Normal control – vehicle treated, 2. Disease control – Al treated, 3. Treatment with V. vinifera (250 mg/kg) after Al induction, 4. Treatment with V. vinifera (500 mg/kg) after Al induction.

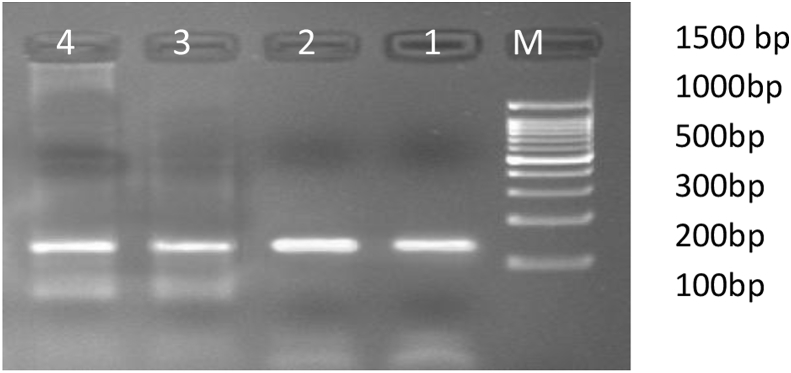

Fig. 2.

Figure showing the 132 bp PCR amplification product of Tau gene.

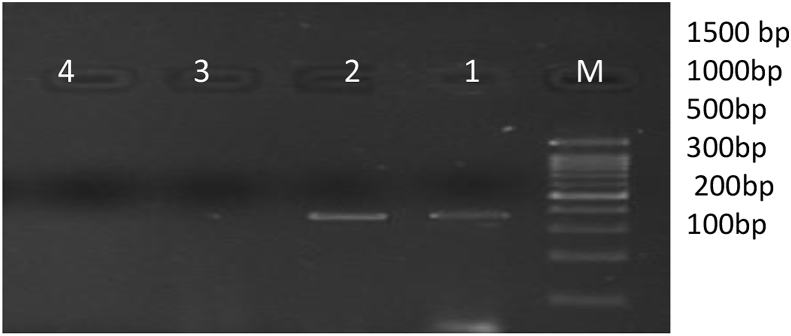

Fig. 3.

Figure showing the 340 bp PCR amplification product of APP gene.

Table 1.

Effect of V. vinifera on mean time spent in the target quadrant (seconds) on Al induced rats in the probe trials.

| S. No | Groups | Mean ± S.E.M (s) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Control | 34.1 ± 0.44 |

| 2. | Disease control | 19.0 ± 0.51* |

| 3. | V. vinifera-250 mg/kg | 33.1 ± 0.61@ |

| 4. | V. vinifera-500 mg/kg | 31.2 ± 0.43@ |

A value of p ≤ 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. *p < 0.05 when compared to control, @p < 0.05 when compared to disease control.

Table 2.

Effect of V. vinifera on escape latencies (seconds) on Al induced rats in the acquisition trials.

| S. No | Groups | Mean ± S.E.M (s) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Control | 51.6 ± 0.84 |

| 2. | Disease control | 69.8 ± 1.15* |

| 3. | V. vinifera-250 mg/kg | 53.6 ± 0.80@ |

| 4. | V. vinifera-500 mg/kg | 53.8 ± 0.53@ |

A value of p ≤ 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. *p < 0.05 when compared to control, @p < 0.05 when compared to disease control.

Table 3.

Effect of V. vinifera on Tau mRNA levels in aluminum induced AD.

| S. No | Groups | Mean ± S.E.M |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Control | 0.19 ± 0.0170 |

| 2. | Disease control | 1.07 ± 0.0347** |

| 3. | V. vinifera-250 mg/kg | 0.11 ± 0.0221@ |

| 4. | V. vinifera-500 mg/kg | 0.19 ± 0.0298@ |

In the present study we studied the effect of V. vinifera on the mRNA expression of APP, bands for APP gene were expressed in the normal vehicle treated animals and disease control animals, the treatment with different doses of V. vinifera (3 and 4) inhibited the expression of the APP, this indicates that V. vinifera acts as a potent anti-APP agent, further research has to be extensively carried out to establish the molecular mechanism of action.

A value of p ≤ 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. **p < 0.001 when compared to control, @p < 0.001 when compared to disease control.

Table 4.

Effect of V. vinifera on MDA levels (nmol/g) and MPO levels (U/g) of rats induced with AD.

| S. No | Groups | MDA(nmol/g) | MPO(Units/g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Control | 49.38 ± 0.33 | 3.38 ± 0.05 |

| 2. | Disease control | 99.41 ± 0.56* | 66.8 ± 0.41** |

| 3. | V. vinifera-250 mg/kg | 50.26 ± 0.94** | 5.71 ± 0.08@@ |

| 4. | V. vinifera-500 mg/kg | 48.94 ± 0.43** | 3.57 ± 0.04@@ |

MDA levels: All data was analyzed by t-test. Data presented are mean ± SEM (n = 10). A value of p ≤ 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. *p < 0.01 when compared to control, **p < 0.001 when compared to disease control.

MPO levels: All data was analyzed via t-test. Data presented are mean ± SEM (n = 10). A value of p ≤ 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. **p < 0.001 when compared to control, @@p < 0.001 when compared to disease control.

Table 5.

Effect of V. vinifera on Acetylcholinesterase enzyme activity (μmol/min/mg of protein) in Al induced AD in rat whole brain.

| S. No | Groups | Mean ± S.E.M(μmol/min/mg) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Control | 0.027 ± 0.0002 |

| 2. | Disease control | 0.148 ± 0.0010** |

| 3. | V. vinifera-250 mg/kg | 0.069 ± 0.0020@ |

| 4. | V. vinifera-500 mg/kg | 0.030 ± 0.0008@ |

A value of p≤ 0.001 was considered as statistically significant. ∗∗p < 0.001 when compared to control, @p < 0.001 when compared to disease control.

3.1. Histopathological analysis

Histopathological observations indicate that brains of Al treated groups exhibit the presence of amyloid plaques, formation of tangles, edema accompanied by disruption of neurons, gliosis, spongiosis, severe neutrophilic infiltration, formation of vacuoles, disruption of nucleus and congestion in blood vessels, indicative of pathological and inflammatory events by Al [15]. It was also reported that Al damages the hippocampus and cortex [16]. In the present study, Al induced deficits were accompanied by the expression of Tau tangles and beta-amyloid plaques formation along with formation of edematous vacuoles, spongiosis, gliosis, and congestion in blood vessels, treatment with V. vinifera produced a significant improvement in the behavioral, biochemical and histological events when compared to disease control animals.

In the present investigation, administration of V. vinifera (250, 500 mg/kg) significantly recovered the memory deficits produced by Al by mitigating pathological changes (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Microscopic study of rat hippocampus in 60, 100× magnification. A.) Control rat brain showing normal histological structure. B.) Rats exposed to 100 mg/kg of Al clearly showing the presence of neurofibrillary tangles (B1), amyloid plaques and edematous vacuoles (B2) severe neutrophilic infiltration, congestion in blood vessels and pericellular edema (B3). C.) Rats administered with 250 mg/kg of V. vinifera showing mild edema and gliosis. D.) Demented rat treated with Vitis (500 mg/kg) showing the normal histological structure.

4. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the behavioral, biochemical and histopathological changes caused by chronic Al exposure and the promising effects of V. vinifera treatment. In Morris water maze test for spatial memory, chronic administration of Al impaired memory and learning. On chronic exposure, Al has been shown to accumulate in all the regions of the rat brain, the maximum being in hippocampus, which is the site of memory and learning [17], [18]. The animals administered with Al developed an AD like condition and suffered from impairment in memory and learning. It is proposed that cholinergic neural system in the hippocampus is the main key involved in spatial memory deficits. Hence, its dysfunction induces deficits in spatial learning tasks in rats. In the present study, Al caused memory impairment in rats as shown by the results in MWM test. V. vinifera improved memory in Al induced rats as evidenced by significant decrease in latency time [Table 2]. Vitis treated animals also exhibited improved target quadrant preferences as shown by the time spent in target quadrant zone [Table 1]. From the results, it is clear that Al caused a definite cognitive decline in the Al treated groups. This cognitive decline was reversed by Vitis treated animals which improved the performance of Al induced rats in the Morris water maze test.

Vitis treatment produced a significant improvement in cognitive function in Al treated Alzheimer's rats. The degree of activity was more in 500 mg/kg treated group rats, as the plant is an excellent source of antioxidants and also acts as a central cholinomimetic agent. The cholinergic system gets disrupted in the Alzheimer's affected group [19], and this was confirmed by the increase in the escape latencies of disease control animals. Hence, these activities of the plant might be responsible for the improvement of spatial memory by increasing cholinergic activity in the present study.

The behavioral study indicated that the chronic Al exposure followed by the treatment with V. vinifera produced a significant improvement in the behavioral parameters of the animals; further biochemical parameters were also evaluated.

The amyloid plaques are the products obtained from the sequential cleavage of APP, while the tangles are produced due to abnormal hyperphosphorylation of microtubule stabilizing protein called Tau. Al induced animals produced significant expression of Tau mRNA [Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Table 3] and APP mRNA Fig. 1, Fig. 3 which is indicative of the presence of tangles and amyloid plaques. This was further confirmed in the histological studies where clear beta amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles were observed in rats induced with AD Fig. 4. V. vinifera being rich in phytoconstituents decreased the mRNA expression of APP in rats and cleared the Tau tangles.

Even though the brain accounts for less than 2% of the bodyweight, it consumes 20% of the basal oxygen up take [20]. Lipid peroxidation is well recognized mechanism of cellular injury in biological system of plants and animals. AD condition increases oxidative stress by increase in lipid peroxidation, as evidenced by significant increase in the Malondialdehyde (MDA) levels Table 4. The mechanism involves a process whereby unsaturated lipids are oxidized to form radical species as well as toxic by-products. Polyunsaturated lipids are more susceptible for oxidative cellular damage and react to form lipid peroxides. Lipid peroxides are unstable themselves and undergo decomposition to form sequel of carbonyl compounds, which further react to form MDA. The highly polyunsaturated lipids in brain tissue are susceptible to oxidative damage due to a high level of oxygen consumption and the post mitotic state of neurons [21].

Al is reported to heighten the peroxidative effect of Fe2+ and this plays an indirect role in causing the oxidative damage by lipid peroxidation. Al administration is reported to induce the oxidative stress leading to the damage of lipids, proteins and antioxidant defense system. Increased levels of free radicals initiate the oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids leading to lipid peroxidation and results in protein carbonylation. Lipid peroxides further lead to production of more stable compounds like malondialdehyde (MDA), 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE) and acrolein, which initiates oxidative stress [22], [23].

The increased free radical activity appears to fuel Alzheimer's pathology. Oxidative damage to lipids (lipid peroxidation) and proteins (protein carbonyl{pc} formation) initially results in an alteration of cell structure, in activation of enzymes, followed by loss of normal physiological cell function. This Reactive Oxygen Metabolites (ROM) attack the cell membranes resulting in increased membrane fluidity and permeability leading to the oxidative destruction of cellular membranes and cell lysis and eventually cell death. This oxidative stress resulting from 4-HNE can lead to delayed neuronal death in the frontal cortex and is associated with AD.

Inflammation is another major hallmark in the AD brain. Myeloperoxidase (MPO) is a potent catalyst for the generation of cytotoxic oxidants. Myeloperoxidase (MPO) expression increased in tissue with Alzheimer pathology; it has been described in human brain lysates [24] and co-localized with amyloid plaques and activated microglia in both the neocortex and the molecular layer of the hippocampus in AD. Epidemiological studies indicate an increased incidence of Alzheimer's with increased myeloperoxidase expression due to the polymorphism in the myeloperoxidase promoter region [25]. It was found that V. vinifera dose-dependently inhibited the activity of myeloperoxidase. In this study Vitis produced good anti-inflammatory activity by reducing the levels of MPO, Table 4 which was also supported by the histopathological evaluation, Fig. 4 Al induced animals showed immense neutrophilic infiltration, edema, gliosis, spongiosis along with congestion in blood vessels which is an clear indicative of inflammation in AD. Treatment with Vitis reduced inflammation to much extent with both the doses. This indicates that inhibition of myeloperoxidase activity may prove to be a valuable therapeutic target beyond general antioxidant regimens to slow oxidatively mediated damage in AD.

Guan [26] suggested that there is a close relationship between oxidative stress and modifications of nicotinic (nAChR) and muscarnic receptors (mAChR) which play an important role in the pathogenesis of AD. Further, loss of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors leads to increased β-amyloid oligomer accumulation in mouse model of AD [27]. The cholinergic receptors are highly vulnerable to oxidative stress, since brain utilizes more amount of oxygen and its cell membranes are highly enriched in oxyradical-sensitive polyunsaturated fatty acids. This results oxidation of DNA and RNA that has been observed commonly in neurodegenerative diseases, where RNA appears to undergo higher degree of oxidation than DNA. Studies suggest that RNA oxidation is involved in early stages of AD [28]. Hence, RNA oxidation is involved in AD, and its improvement gives significant indication of rectification of learning and memory.

Apart from these activities, Vitis prevents DNA and RNA fragmentation [29] besides its high antioxidant capacity, such that the structural modifications of cholinergic receptors may be prevented. This antioxidant activity along with cholinomimetic activity might be another reason for the improvement of cognition and memory Table 5. The pathogenic mechanisms of AD are considerably complex, so that most of the treatments are unable to take every aspect into account.

5. Conclusion

Treatment with Vitis has shown significant protective effect which may be due to reduction in oxidative stress, inflammation and also showed alteration in gene expression of APP and Tau. The neuroprotection offered by V. vinifera against Al induced AD was confirmed by the histopathological studies. The findings of the present study revealed that Vitis markedly reduced the formation of amyloid plaques, Tau tangles and also reduced the oxidative stress, inflammation and improved cholinergic actions. This was further confirmed by the histological evaluation. This work suggests that V. vinifera may prove to be useful entity in the treatment of AD.

Sources of funding

Authors are grateful to University Grants Commission for providing financial assistance (Grant-UGC/RGNF-4878).

Conflict of interest

None.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Transdisciplinary University, Bangalore.

References

- 1.Greger J.L. Aluminum metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 1993;13:43–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.13.070193.000355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawahara M. Effects of aluminum on the nervous system and its possible link with neurodegenerative diseases. J Azheimers Dis. 2005;8:171–182. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-8210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zatta P. In vivo and in vitro effects of aluminum on the activity of mouse brain acetyl cholinesterase. Brain Res Bull. 2002;59:41–45. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(02)00836-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pallavi Sethi, Jyoti Amar, Hussain Ejaz, Sharma Deepak. Curcumin attenuates aluminium-induced functional neurotoxicity in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;93:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hardy J.A., Higgins G.A. Alzheimer's disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992 Apri10;256(5054):184–185. doi: 10.1126/science.1566067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michael Farzan, Schnitzler Christine E., Vasilieva Natalya, Leung Doris, Choe Hyeryun. BACE2, a beta-secretase homolog, cleaves at the beta site and within the amyloid-beta region of the amyloid-beta precursor protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(17):9712–9717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160115697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sinha S., Anderson J.P., Barbour R., Basi G.S., Caccavello R., Davis D. Purification and cloning of amyloid precursor protein beta-secretase from human brain. Nature. 1999;402(6761):537–540. doi: 10.1038/990114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gulya K., Rakonczay Z., Kasa P. Cholinotoxic effects of aluminum in rat brain. J Neurochem. 1990;54(3):1020–1026. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb02352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Markesbery W.R. Oxidative stress hypothesis in Alzheimer's disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997;23(1):134–147. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(96)00629-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris R.G., Garrud P., Rawlins J.N., O'Keefe J. Place navigation impaired in rats with hippocampal lesions. Nature. 1982;297(5868):681–683. doi: 10.1038/297681a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohkawa H., Ohishi N., Yaki K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal Biochem. 1979;95(2):351–358. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90738-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mullane K.M., Kraemer R., Smith B. Myeloperoxidase activity as a quantitative assessment of neutrophil infiltration into ischemic myocardium. J Pharmacol Methods. 1985;14(3):157–167. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(85)90029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellman G.L., Courtney K.D., Valentino Andress, Jr., Featherstone R.M. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem Pharmacol. 1961;7(2):88–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Longo U.G., Franceschi F., Ruzzini L., Rabitti C., Morini S., Maffulli N. Characteristics at hematoxylin and eosin staining of ruptures of the long head of the biceps tendon. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(8):603–607. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2007.039016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kakkar Vandita, Kaur Indu Pal. Evaluating potential of curcumin loaded solid lipid nanoparticles in aluminium induced behavioral, biochemical and histopathological alterations in mice brain. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49:2906–2913. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rebai O., Djebli N.E. Chronic exposure to aluminum chloride in mice: exploratory behaviors and spatial learning. Adv Biol Res. 2011;2:26–33. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Julka D., Vasishta R.K., Gill K.D. Distribution of aluminum in different regions and body organs of rat. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1996;52:181–192. doi: 10.1007/BF02789460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amarpreet Kaur, Joshi Kusum, Minz Ranjana Walker, Gill Kiran Dip. Neurofilament phosphorylation and disruption: a possible mechanism of chronic aluminium toxicity in Wistar rats. Toxicology. 2006;219(1–3):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sreemantula Satyanarayana, Nammi Srinivas, Kolanukonda Rajabhanu, Koppula Sushruta, Boini Krishna M. Adaptogenic and nootropic activities of aqueous extracts of Vitis vinifera (grape seed): an experimental study in rat model. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2005;5:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rapaka Deepthi, Bitra Veera Raghavulu, Medapati Jayarami reddy, Akula Annapurna. Calcium regulation and Alzheimer's disease. Asian Pac J Trop Dis. 2014;4(2):S513–S518. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maki Richard A., Tyurin Vladimir A., Lyon Robert C., Hamilton Ronald L., DeKosky Steven T., Kagan Valerin E. Aberrant expression of myeloperoxidase in astrocytes promotes phospholipid oxidation and memory deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2008;284(5):3158–3169. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807731200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith C.D., Carney J.M., Tatsumo T., Stadtman E.R., Floyd R.A., Markesbery W.R. Protein oxidation in aging brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;663:110–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb38654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ansari M.A., Scheff S.W. Oxidative stress in the progression of Alzheimer's disease in the frontal cortex. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2010;69(2):155–167. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181cb5af4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jolivalt C., Leninger-Muller B., Drozdz R., Naskalski J.W., Siest G. Apolipoprotein E is highly susceptible to oxidation by myeloperoxidase, an enzyme present in the brain. Neurosci Lett. 1996;210(1):61–64. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12661-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reynolds W.F., Rhees J., Maciejewski D., Paladino T., Sieburg H., Maki R.A. Myeloperoxidase polymorphism is associated with gender specific risk for Alzheimer's disease. Exp Neurol. 1999;155(1):31–41. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guan Z.Z. Cross-talk between oxidative stress and modifications of cholinergic and glutaminergic receptors in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2008;29(7):773–780. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hernandez C.M., RaKez Kayed, Hui Zheng, Sweatt J David, Dineley Kelly T. Loss of alpha 7 nicotinic receptors enhances beta-amyloid oligomer accumulation exacerbating early-stage cognitive decline and septohippocampal pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2010;30(7):2442–2453. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5038-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nunomura A., Perry G., Pappolla M.A., Wade R., Hirai K., Chiba S. RNA oxidation is a prominent feature of vulnerable neurons in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 1999;19(6):1959–1964. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-01959.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anekonda Thimmappa S., Reddy P. Hemachandra. Can herbs provide a new generation of drugs for treating Alzheimer's disease? Brain Res Rev. 2005;50:361–376. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]