Origin and functions of intermittent transitions among sleep stages, including brief awakenings and arousals, constitute a challenge to the current homeostatic framework for sleep regulation, focusing on factors modulating sleep over large time scales. Here we propose that the complex micro-architecture characterizing sleep on scales of seconds and minutes results from intrinsic non-equilibrium critical dynamics.

Keywords: brain rhythms, cortical dynamics, criticality, sleep regulation, VLPO

Abstract

Origin and functions of intermittent transitions among sleep stages, including brief awakenings and arousals, constitute a challenge to the current homeostatic framework for sleep regulation, focusing on factors modulating sleep over large time scales. Here we propose that the complex micro-architecture characterizing sleep on scales of seconds and minutes results from intrinsic non-equilibrium critical dynamics. We investigate θ- and δ-wave dynamics in control rats and in rats where the sleep-promoting ventrolateral preoptic nucleus (VLPO) is lesioned (male Sprague-Dawley rats). We demonstrate that bursts in θ and δ cortical rhythms exhibit complex temporal organization, with long-range correlations and robust duality of power-law (θ-bursts, active phase) and exponential-like (δ-bursts, quiescent phase) duration distributions, features typical of non-equilibrium systems self-organizing at criticality. We show that such non-equilibrium behavior relates to anti-correlated coupling between θ- and δ-bursts, persists across a range of time scales, and is independent of the dominant physiologic state; indications of a basic principle in sleep regulation. Further, we find that VLPO lesions lead to a modulation of cortical dynamics resulting in altered dynamical parameters of θ- and δ-bursts and significant reduction in θ–δ coupling. Our empirical findings and model simulations demonstrate that θ–δ coupling is essential for the emerging non-equilibrium critical dynamics observed across the sleep–wake cycle, and indicate that VLPO neurons may have dual role for both sleep and arousal/brief wake activation. The uncovered critical behavior in sleep- and wake-related cortical rhythms indicates a mechanism essential for the micro-architecture of spontaneous sleep-stage and arousal transitions within a novel, non-homeostatic paradigm of sleep regulation.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT We show that the complex micro-architecture of sleep-stage/arousal transitions arises from intrinsic non-equilibrium critical dynamics, connecting the temporal organization of dominant cortical rhythms with empirical observations across scales. We link such behavior to sleep-promoting neuronal population, and demonstrate that VLPO lesion (model of insomnia) alters dynamical features of θ and δ rhythms, and leads to significant reduction in θ–δ coupling. This indicates that VLPO neurons may have dual role for both sleep and arousal/brief wake control. The reported empirical findings and modeling simulations constitute first evidences of a neurophysiological fingerprint of self-organization and criticality in sleep- and wake-related cortical rhythms; a mechanism essential for spontaneous sleep-stage and arousal transitions that lays the bases for a novel, non-homeostatic paradigm of sleep regulation.

Introduction

Sleep periods exhibit numerous transitions among sleep stages and short awakenings, with intermittent fluctuations within sleep stages that trigger micro-states and brief arousals (Halász, 1998; Hirshkowitz, 2002; Lo et al., 2002). Such behavior is typically observed in non-equilibrium systems characterized by multicomponent nonlinear feedback interactions and exhibiting critical behavior, with irregular alternation between active and quiescent phases (Bak, 1996; Chialvo, 2010; Munoz, 2018). This constitutes a challenge to the current homeostatic framework for sleep regulation, which considers sleep as an equilibrium process, and focuses on factors modulating sleep over large time scales, such as homeostatic sleep drive, sleep propensity and inertia, and ultradian and circadian rhythms (Borbély and Achermann, 1999; Saper et al., 2005; Brown et al., 2012). Existing homeostatic models, although successfully providing a good description of consolidated sleep and wakefulness over time scales of hours (Borbély and Achermann, 1999; Achermann and Borbély, 2003; Saper et al., 2001, 2010), do not capture the emergent complexity of transient and abrupt behaviors at scales of seconds and minutes (Lo et al., 2004; Olbrich et al., 2011), and do not account for the related dynamics of bursts in cortical rhythms.

The intrinsic fluctuations in cortical rhythmic activity in response to feedback interactions among sleep- and wake-promoting neuronal groups, and the corresponding complex temporal patterns of intermittent transitions in sleep micro-architecture, suggest that critical dynamics may underlie sleep regulation at small time scales, in parallel with the well established homeostatic behavior at large time scales. Such hypothesis is further motivated by recent work showing a peculiar coexistence of power-law and exponential probability distributions for the durations of brief awakenings/arousals and sleep bouts, in both humans and animal models (Lo et al., 2002, 2004; Blumberg et al., 2005; Behn et al., 2007; Dvir et al., 2018). This scenario is closely reminiscent of non-equilibrium systems self-tuning at criticality, where a quiescent phase with exponential dynamics coexists with an active phase characterized by bursts/avalanches with power-law distributed sizes and durations (Boffetta et al., 1999; Chialvo, 2010; Munoz, 2018). Because brief awakenings/arousals can be viewed as “active” states of the brain that interrupt the “inactive” phase represented by sleep periods, the coexistence of power-law distributed arousal durations with sleep bouts durations following exponential behavior has been interpreted as a fingerprint of criticality in sleep dynamics (Lo et al., 2004, 2013).

To test this hypothesis, we investigate the dynamics of dominant brain waves in the sleep–wake cycle of rats in relation to the neuronal circuitry responsible for wake and sleep control. In particular, we focus on the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus (VLPO), a key sleep promoting brain region (Sherin et al., 1996), and study whether alterations in the sleep–wake cycle are mirrored by a reorganization of dominant brain rhythms. The sleep–wake cycle of rats is largely dominated by the δ and θ rhythm. During non-rapid eye movement sleep (NREM) sleep, cortical activity is characterized by δ rhythm, low-frequency high-amplitude oscillations referred to as slow-wave activity (Steriade et al., 1993), whereas REM sleep and arousals/wake state are characterized by θ rhythm, desynchronized and localized oscillations of higher frequency and lower amplitude (Brown et al., 2012). Lesions of the central cluster of the VLPO lead to a large decrease in delta power and NREM sleep time, and a fragmentation of the sleep–wake cycle (Lu et al., 2000). REM sleep may also be affected by lesions in the VLPO area, especially in the medial and dorsal extended VLPO region (Vetrivelan et al., 2012). However, the influence of VLPO neurons on the dynamics and temporal organization of δ and θ waves during the sleep–wake cycle has not been investigated.

To this aim, we analyze long-term continuous EEG recordings in control rats and rats with lesions in the VLPO, and dissect emergent signatures of criticality in the dynamics of θ- and δ-bursts in relation to VLPO neuronal integrity. We link alterations of the sleep–wake cycle with non-equilibrium properties of the underlying dynamics, providing first evidence for a criticality-based framework of sleep regulation that unifies sleep stage and arousal transitions with basic dynamics of dominant cortical rhythms.

Materials and Methods

Experimental setup and statistical analysis

Twelve pathogen-free, 12- to 16-week-old male Sprague-Dawley rats (300–365 g; Harlan) were used for this study. Data analyzed here were selected from a previously presented study (Vetrivelan et al., 2012) with 7 control and 34 VLPO-lesioned rats. The VLPO-lesioned group used for the present study includes all animals with >85% cell loss in the VLPO; n = 7 of the entire cohort of 34 VLPO-lesioned rats. One control rat and one VLPO-lesioned rat were excluded from the final analysis after the preprocessing procedure. For the purpose of our study of sleep microdynamics, we selected and analyzed rats with <10% artifacts in the EEG (see Data preprocessing). The experimental procedure is briefly summarized below. For further details regarding data collection and protocol, please refer to Vetrivelan et al. (2012).

Rat surgery.

Animals were anesthetized with chloral hydrate (350 mg/kg body weight, i.p.) and the fur over the skull was shaved, and the skin was prepped with betadine and alcohol. The animals were then fixed in a stereotaxic frame. All surgery was conducted using sterile autoclaved instruments and under aseptic conditions. To produce VLPO lesions, orexin-B-saporin (OX-SAP; Advanced Targeting Systems) was injected into the VLPO as described below. Skin (∼1 cm) was incised and small burr holes were drilled in the skull corresponding to the VLPO coordinates. A glass micropipette (tip diameter 10–20 μm) was then lowered to coordinates (AP: −0.6 from bregma, L: 1.00, DV: 8.5) corresponding to the VLPO as per the rat atlas of Paxinos and Watson (2004) and OX-SAP (200 nl of 0.1% solution) was injected using a compressed air delivery system (Amaral and Price, 1983). The micropipette was then left in place for 5 min and slowly withdrawn. Control animals received saline (vehicle) injections into the VLPO. Following the injections, four EEG screw electrodes were implanted into the skull, in the frontal (2) and parietal bones (2) of each side, and two flexible EMG wire electrodes were placed into the neck muscles for the collection of sleep–wake data. Four burr holes were made in the skull (1 mm rostral and 3 mm lateral; 3 mm caudal and 3 mm lateral) and EEG electrodes were inserted into those burr holes so that they would be close to dura mater. EMG wire electrodes were placed onto the neck extensor muscles on either side. The free ends of the leads were soldered into a socket that was attached to the skull with dental cement, and the incision was then closed by wound clips (Lu et al., 2000, 2002).

EEG recording across dark and light and sleep–wake analysis.

EEG recordings from each rat were performed on Day 20 post-lesion using Grass polygraph. The rats were connected via flexible recording cables to a commutator, which in turn was connected to a Grass polygraph and computer. The rats were habituated to the connecting cables and the recording room conditions for 2 d and then uninterrupted recordings of the EEG/EMG (sampling rate 256 Hz) and time-lock video were conducted for 48 h (2 d, 12 h light/dark) beginning of Day 20 postlesion. EEG signals were recorded continuously from the frontal and parietal electrode on both left and right hemisphere. The parietal electrode picks up θ rhythm from the hippocampus during REM sleep; both the frontal and parietal electrodes pick up θ rhythm during wakefulness. Hippocampal θ rhythm can be also present during wakefulness, mainly during locomotion and cognitive wakefulness. The signal analyzed in this study is the difference between frontal and parietal EEG electrode potentials (frontal–parietal EEG) from one hemisphere (ipsilateral). The EEG/EMG data of each rat was divided into 12 s epochs and visually scored as wake, NREM sleep, or rapid eye movement (REM) sleep using scoring criteria previously described (Lu et al., 2000). Wakefulness was identified by the presence of desynchronized-EEG and high-EMG activity. NREM sleep was identified by the presence of a high-amplitude, slow-wave EEG and low-EMG activity relative to that of waking. REM sleep was identified by the presence of regular theta activity on EEG, coupled with low-EMG activity relative to that of NREM sleep. When two states (for example, NREM sleep and wake) occurred within a 12 s epoch, the epoch was scored for the state that predominated. Scoring was done before histological examination, so the scorer was unaware of the extent of the lesions. The daily percentage of time spent in wake, NREM sleep, and REM sleep and frequency and durations of episodes of each stage were calculated.

Histology.

On completion of the recordings, the rats were deeply anesthetized (chloral hydrate, 500 mg/kg) and transcardially perfused with 100 ml saline, followed by 500 ml of neutral phosphate buffered formalin (ThermoFisher Scientific). The brains were removed and processed for Nissl staining. For this, the harvested brains were sectioned in the coronal plane on a freezing microtome into four series of 40 μm sections and one series was mounted on gelatin-coated slides, washed in H2O, and washed in PBS. Sections were then incubated in 0.25% thionin in 0.1 m acetate buffer solution for 2 min, differentiated in graded ethanols, delipidated in xylene and coverslipped (Lu et al., 2000).

Statistical analysis.

Power-law exponent and fitting parameters for burst duration distributions were evaluated for each rat and condition (24 h: 12 h dark/light periods) in both the control group and VLPO. Pairwise comparisons between groups and conditions were conducted (see Figs. 2 and 3). The temporal correlations detrended fluctuation analysis (DFA) exponent (see Fig. 11) and θ–δ coupling Spearman's correlation coefficient (see Fig. 12) were evaluated for each rat in both groups, and then pairwise comparisons between conditions and groups were conducted. Individual group data were tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Pairwise comparisons were conducted using Students two-tailed t test with Welch's correction, unless the Shapiro–Wilk test was significant, in which case the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test was used. Paired tests: control 12 h dark versus 12 h light period; VLPO-lesioned 12 h dark versus 12 h light period. Comparisons between control and VLPO-lesioned group were performed for each condition (12 h dark/light period), and for the 24 h period. Surrogate tests were used to test significance of correlations between theta- and delta-bursts, and are described in Data analysis. All statistical tests were performed in MATLAB (MathWorks).

Figure 2.

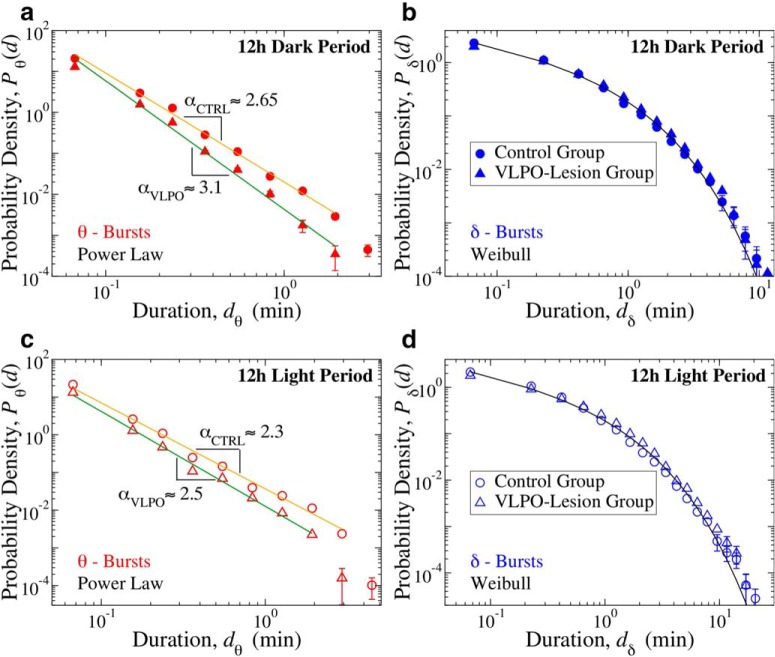

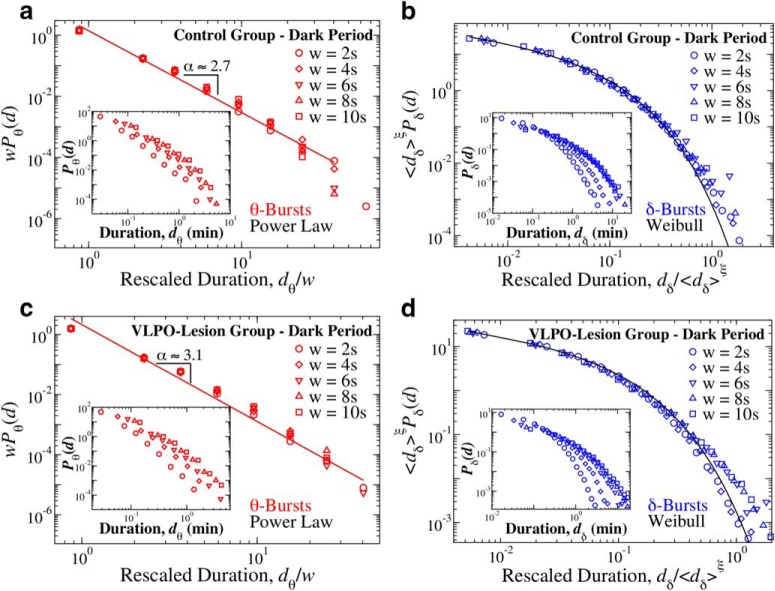

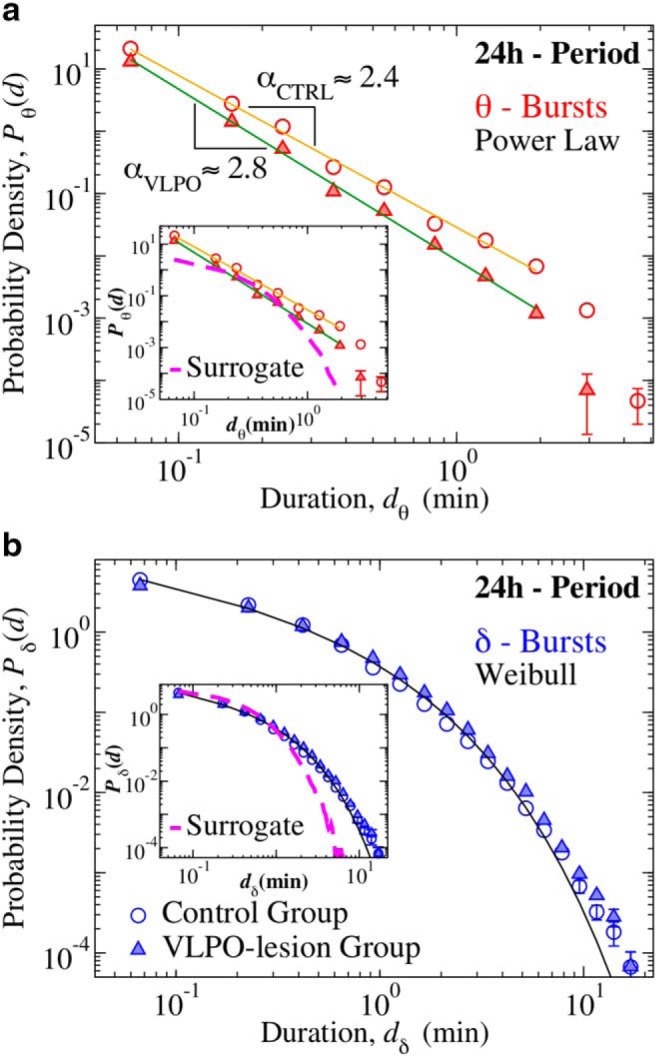

Durations of θ and δ-bursts across the 24 h sleep–wake cycle follow different statistics that are modulated by VLPO. a, Distribution of θ-burst durations for control (open circles) and VLPO lesioned rats (full triangles) over the 24 h period (pooled data, 6 control and 6 VLPO-lesioned rats). The distribution exhibits a power-law behavior in both groups (colored tick lines). Lesions in the VLPO area cause a significant increase in the power-law exponent from αCTRL = 2.44 ± 0.07 to αVLPO = 2.75 ± 0.05 (exponent ± error on fit), indicating a reduced probability for long θ-bursts (Group comparison, t test, p = 0.0005). b, Distribution of δ burst durations for control (open circles) and VLPO lesioned rats (full triangles) over 24 h period (pooled data). In contrast to the statistics of θ-bursts, δ-bursts durations follow Weibull distributions. Weibull parameters are not significantly affected by lesions of the VLPO (βCTRL = 0.64, λCTRL = 0.38; βVLPO = 0.70, λVLPO = 0.54). The black tick line is a Weibull fit of the distribution for control rats. All durations are calculated using a window size w = 4 s and threshold Th = 1 on the ratio Rθδ (Fig. 1). Insets, Distributions of surrogate θ- and δ-burst durations markedly deviate from the original distributions. Error bars δP are calculated for each value of the distributions as δP = ()/dD, and where not shown are smaller than the symbol size. Error bar calculation and binning procedure are described in Materials and Methods, Data analysis.

Figure 3.

Critical behavior represented by duality of power-law and Weibull distribution for θ- and δ-bursts characterizes cortical activity during both dark and light periods. a, Probability distributions of θ-burst durations for control (full circles) and VLPO-lesioned (full triangles) rats over the 12 h dark (lights-off) period (pooled data, 6 control and 6 VLPO-lesioned rats) follow a power-law with exponent αCTRL = 2.66 ± 0.07 and αVLPO = 3.13 ± 0.12 (exponent ± error on fit). Both groups exhibit an exponent larger than in the 24 h sleep–wake cycle (Fig. 2), in particular VLPO-lesioned rats, and the difference between the two groups becomes more pronounced (Control vs VLPO group comparison: t test, p = 0.003). b, Probability distributions of δ-burst durations for control (full circles) and VLPO-lesioned (full triangles) rats over 12 h dark (lights-off) period (pooled data) follow a Weibull behavior in both groups, with no significant differences in the fitting parameters (βCTRL = 0.66, λCTRL = 0.36; βVLPO = 0.72, λVLPO = 0.49). c, Probability distributions of θ-burst durations for control (open circles) and VLPO-lesioned (open triangles) rats over the 12 h lights-on period (pooled data, 6 control and 6 VLPO-lesioned rats) also follow a power-law, but exponents are smaller than in the dark period, with αCTRL = 2.28 ± 0.09 and αVLPO = 2.51 ± 0.07. The difference between the two groups is less pronounced than in dark period (Control vs VLPO comparison: t test, p = 0.131). Paired tests show significant differences between dark and light periods in each group: control dark versus control light t test, p < 0.0005; VLPO dark vs VLPO light t test, p = 0.0010. d, Probability distributions of δ burst durations for control (open circles) and VLPO lesioned (open triangles) rats over 12 h lights-on period (pooled data) also follow a Weibull behavior, with no significant differences in the fitting parameters (βCTRL = 0.70, λCTRL = 0.37; βVLPO = 0.67, λVLPO = 0.62). Black tick lines in c and d show Weibull fits for the distribution of the control group. All durations are calculated using a window size w = 4 s and threshold Th = 1 on the ratio Rθδ (Fig. 1). Error bars are calculated for each value and where not shown are smaller than the symbol size. Error bars δP are calculated for each value of the distributions as δP = ()/dD, and where not shown are smaller than the symbol size. Error bars calculation and binning procedure are described in Materials and Methods, Data analysis.

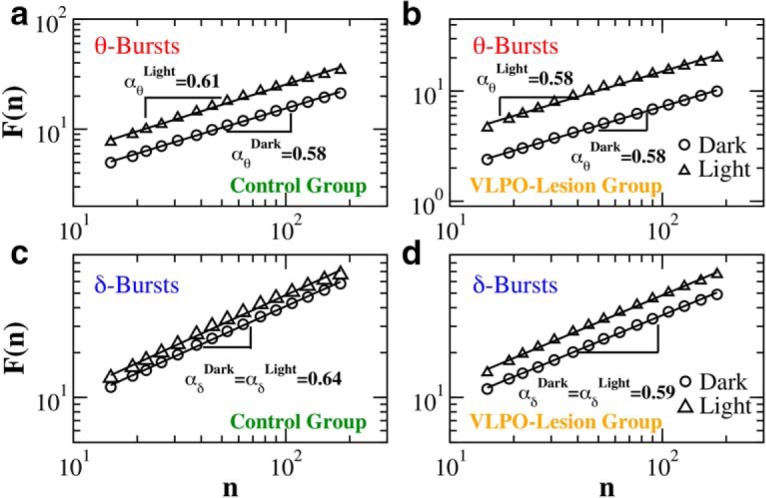

Figure 11.

Long-range power-law correlations in sequences of consecutive θ- and δ-burst durations indicate a dynamical system at criticality. Detrended fluctuation analysis for sequences of θ- and δ-burst durations in control and VLPO-lesioned rats. Burst durations are calculated using a window w = 4 s and threshold Th = 1 on the ratio Rθδ (Fig. 1), and are analyzed separately for 12 h dark/light periods. The rms fluctuation function F(n) is obtained averaging over all rats in the control (a) and VLPO-lesioned group (b), respectively. Log–log plots of F(n) versus the time scale of analysis n, where n is the number of consecutive burst durations, show power-law relations F(n) ∝ nαd over a broad range of scales n. The scaling exponents are significantly larger than 0.5, both in light and dark periods, indicating presence of positive (persistent) long-range correlations in θ-bursts for both control and VLPO-lesioned rats. Similar results are found in sequences of δ-bursts for (c) control and (d) VLPO-lesioned rats. Power-law exponents were obtained from the average rms fluctuation function F(n).

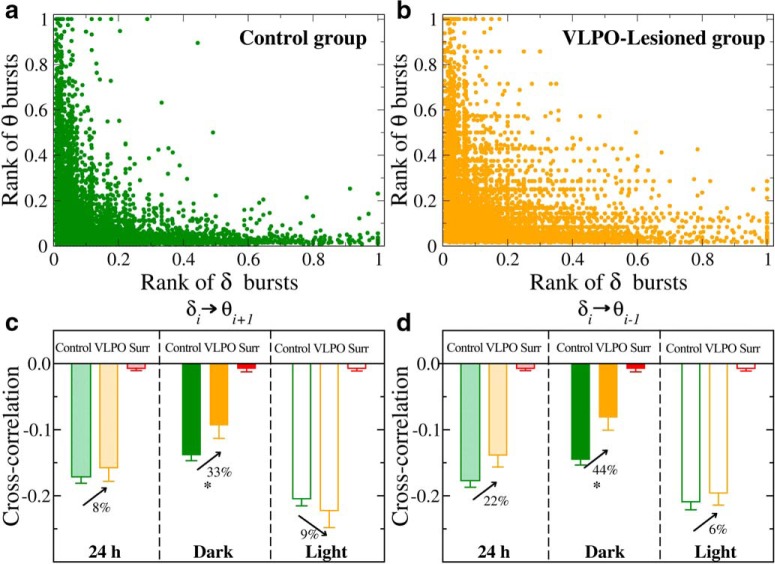

Figure 12.

Coupling between δ- and θ-burst durations indicates a common mechanism regulating the activity of these rhythms across the sleep–wake cycle. Scatter plots and rank correlation analysis demonstrate anti-correlated coupling between consecutive δ- and θ-burst durations. a, Scatter plot of δ burst ranks versus θ burst ranks in the dark period for control rats. Each dot represents a pair formed by a δ-burst and the following θ-burst, with burst durations separately ranked among the δ-bursts and the θ-bursts (longest duration corresponding to highest rank). b, Scatter plot of δ-burst ranks versus θ-burst ranks in the dark period for VLPO-lesioned rats. For each rat group, ranks are calculated separately for each rat and then plotted together. c, d, Average Spearman's cross-correlation coefficient for control and VLPO-lesioned rats in dark, light, and 24 h periods. Anti-correlations between consecutive θ- and δ-bursts are stronger during light than during dark periods in each group. Comparing dark versus light periods, the Student's t test gives p < 0.001 for control rats and p = 0.002 for VLPO-lesioned rats. Importantly, VLPO lesioned rats generally exhibit weaker anti-correlations than the control group, in particular during dark periods, where anti-correlation decreases with ≈35% compared with control rats [Control vs VLPO t test; (c) 24 h, p = 0.159; dark, p = 0.008; light, p = 0.700; (d) 24 h, p = 0.069; dark, p = 0.013; light, p = 0.273]. All correlation coefficients calculated in both groups are significantly different from the corresponding values obtained in the surrogates (red bars) after randomly reshuffling the original order of θ- and δ-bursts (t test, p < 0.001). All durations are calculated using a window w = 4 s and threshold Th = 1 on the ratio Rθδ (as in Fig. 1).

Data preprocessing

EEG recordings were first normalized to zero mean, μ = 0, and unit SD, σ = 1. For each rat, EEG signals were visually inspected and noisy segments were discarded according to the following semiautomatic procedure. Data were first examined to identify most typical noise/artifact waveforms and their specific characteristics, such as amplitude and average duration 〈T〉 expressed in number of sampling points. Based on this preliminary analysis, two amplitude thresholds S1 and s2, with S1 > s2, were introduced. The values of these thresholds are multiples of the EEG signal SD σ, and depend on the specific noise/artifact waveform for each particular rat. Typical values of threshold S1 range between 3.5σ and 6σ, and s2 is between 2.5σ and 4σ. EEG signals were then scanned using a non-overlapping window W1 = 〈T〉/2. Whenever a window W1 contained a significant number of points (e.g., ns > 15; EEG signals were sampled at 256 Hz) with amplitude exceeding the threshold S1, our algorithm identifies an artifact, and a non-overlapping sub-window of size w2 < W1 was used to scan again the identified artifact segment and clean it up. Specifically, this second step works as follows: inside the artifact window W1, segments of length w2 containing points with amplitude exceeding the threshold s2 are sequentially cleaned up by substituting all points in w2 with zeros. An artifact segment w2 that follows a preceding cleaned segment but does not contain points exceeding the threshold s2 is also cleaned; this removes subthreshold points in W1 that belong to the decaying part of an artifact. In this case, such procedure continues and the following sub-windows w2 are also cleaned until the signal crosses zero. These steps are repeated until the entire artifact segment W1 is scanned. Finally, 500 points (≈2 s) are removed from the EEG on both sides of the cleaned artifact segment W1, to eliminate possible pre-artifact and post-artifact influence on the signal. These steps carefully take into account the general slow decaying waveform of some EEG artifacts, and are needed to ensure an optimal cleaning of the data. For all rats in this study W1 = 500 and w2 = 100 data points. At the end of the preprocessing procedure EEG signals were visually inspected to ensure that all noisy segments were properly removed. The total length of removed noisy segments ranges between 5 and 10% of the 48 h recording for each rat. Of the 7 control and 7 VLPO-lesioned rats, 1 control and 1 VLPO rat had >10% of the signal removed after the preprocessing, and correspondingly were removed from the analysis. The code used for EEG preprocessing is available upon request.

Data filtering.

Data were bandpass filtered in the range 0.5–25 Hz using a FIR (finite impulse response) filter designed in MATLAB.

Data analysis

Spectral analysis.

The clean EEG signal is divided in N non-overlapping windows of size w and the spectral power in the δ band (0.5–4 Hz), Sδ, and in the θ band (4–8 Hz), Sθ, is estimated in each window using Welch's method (Welch, 1967). The analysis is performed for several values of the window size w, from 2 to 10 s. Results are generally independent of w, as shown in Figures 5, 6, and 7, and extensively discussed in the main text.

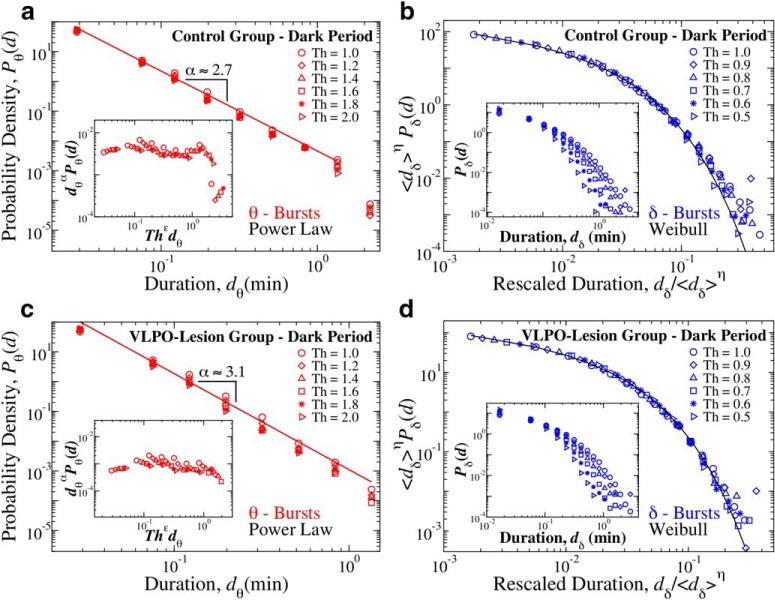

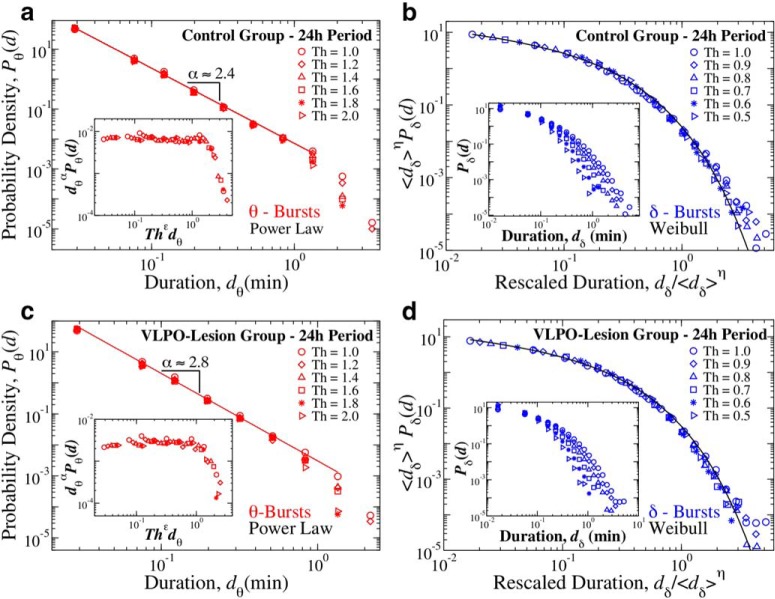

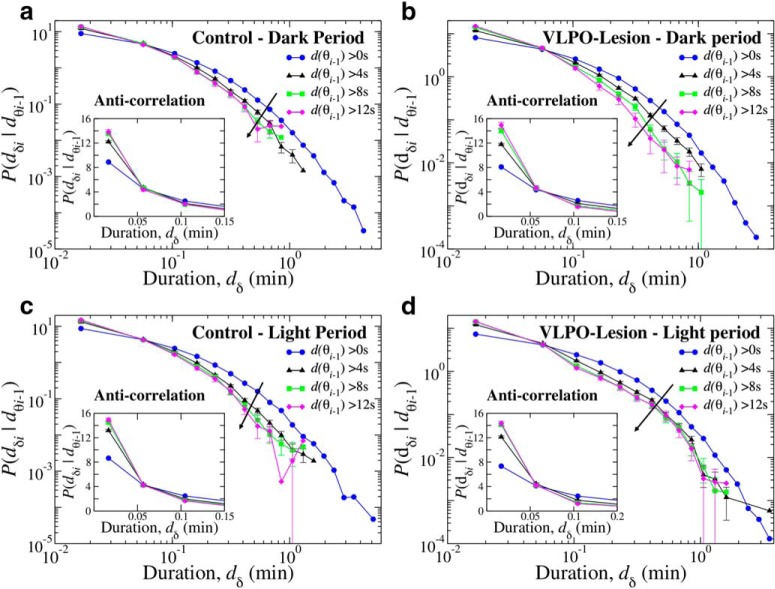

Figure 5.

Distribution of θ- and δ-burst durations in the dark period are independent of the specific threshold Th used to identify bursts and can be described by unique scaling functions. Distribution of θ- and δ-burst durations in the dark period for different threshold values Th on the ratio Rθδ and window size w = 4 s. a, Distribution of θ burst durations for control rats over a 12 h dark period (pooled data). Distributions evaluated using different Th values consistently follow the same power law behavior, with a cutoff that is controlled by Th. Inset, The data collapse onto a universal function fθ when we plot P(d)dα versus Thϵd, with α = 2.65 and ϵ = 0.8. b, Rescaled distribution of δ-burst durations for control rats over a 12 h dark period (pooled data). Distributions are rescaled by 〈dδ〉η, with 〈dδ〉 mean δ-burst duration and η = 1.3. After rescaling, distributions collapse onto a unique function fδ that is well described by a Weibull distribution f(d; λ, β) (thick line), with λ = 0.01 and β = 0.72. Inset, Distributions Pδ for different thresholds (not rescaled). c, Distribution of θ burst durations for VLPO-lesioned rats over a 12 h period (pooled data). Distributions evaluated using different Th values consistently follow the same power law behavior, with a cutoff that is controlled by Th. Data collapse onto a universal function fθ by plotting P(d)dα versus Thϵd with α = 3.1 and ϵ = 0.8. d, Rescaled distribution of δ burst durations for VLPO-lesioned rats over a 12 h dark period (pooled). Distributions are rescaled by 〈dδ〉η, with η = 1.3. After rescaling, the distributions collapse onto a unique function fδ that is close to a Weibull distribution f(x; λ, β) (thick black line), with λ = 0.05 and β = 0.75. Inset, Distributions Pδ for different thresholds (not rescaled).

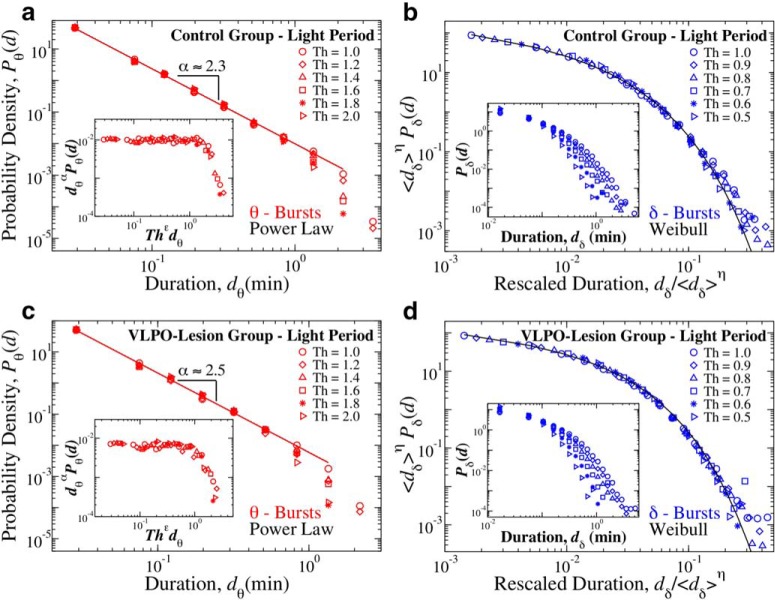

Figure 6.

Distribution of θ- and δ-burst durations in the light period are independent of the specific threshold Th used to identify bursts and can be described by scaling functions. Distribution of θ and δ burst durations in the light period for different threshold values Th on the ratio Rθδ and window size w = 4 s. a, Distribution of θ burst durations for control rats over a 12 h light period (pooled data). Distributions evaluated using different Th values consistently follow the same power law behavior, with a cutoff that is controlled by Th. The data collapse onto a universal function fθ when we plot P(d)dα versus Thϵd, with α = 2.3 and ϵ = 0.8 (inset). b, Rescaled distribution of δ burst durations for control rats over a 12 h light period (pooled data). Distributions are rescaled by 〈dδ〉η, with 〈dδ〉 mean δ-burst duration and η = 1.3. After rescaling, distributions collapse onto a unique function fδ that is close to a Weibull distribution f(d; λ, β) (black line), with λ = 0.04 and β = 0.70. Inset, Distributions Pδ for different thresholds (not rescaled). c, Distribution of θ burst durations for VLPO-lesion rats over a 12 h period (pooled data). Distributions evaluated using different Th values consistently follow the same power law behavior, with a cutoff that is controlled by Th. Inset, Data collapse onto a universal function fθ by plotting P(d)dα versus Thϵd with α = 2.5 and ϵ = 0.8. d, Rescaled distribution of δ burst durations for VLPO-lesion rats over a 12 h light period (pooled). Distributions are rescaled by 〈dδ〉η, with η = 1.3, and collapse onto a unique function fδ that is close to a Weibull distribution f(d; λ, β) (thick black line), with λ = 0.05 and β = 0.74. Inset, Distributions Pδ for different thresholds (not rescaled).

Figure 7.

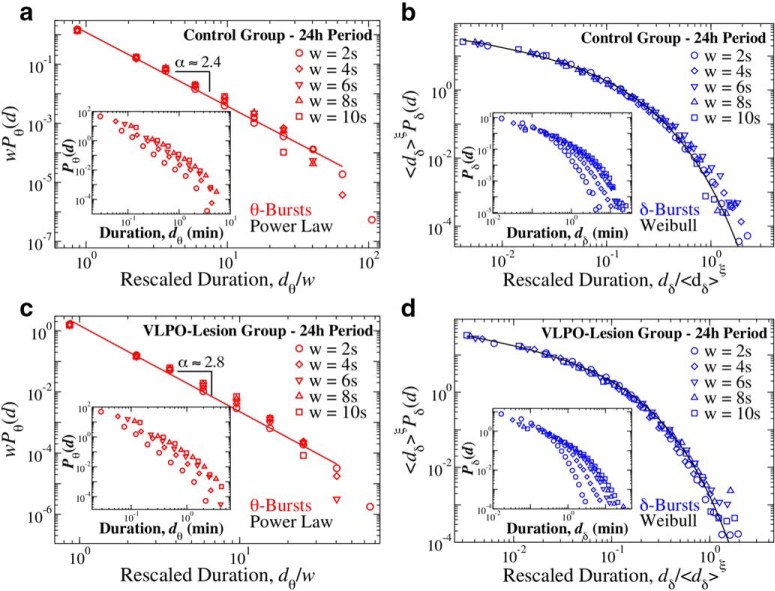

Critical characteristics in the dynamics of bursts of dominant cortical rhythms are independent of the scale of analysis. Distribution of θ and δ-burst durations for different scales of observation defined by window sizes w (Fig. 1). a, Rescaled distribution of θ-burst durations for control rats over a 24 h period (pooled data). Distributions are rescaled by the window size w and consistently show the same power law behavior with α = 2.4 (red line), as proven by the data collapse. Inset, Distributions Pθ for different window sizes w (not rescaled). b, Rescaled distribution of δ-burst durations for control rats over a 24 h period (pooled data). Distributions are rescaled by 〈dδ〉ξ, where 〈dδ〉 is the mean δ-burst duration and ξ = 1, and collapse onto a single function that is well described by a Weibull distribution f(d; λ, β) with λ= 6.18 and β = 0.72 (black line). Inset, Distributions Pδ for different window sizes (not rescaled). c, Rescaled distribution of θ burst durations for VLPO-lesioned rats over a 24 h period (pooled data). Distributions are rescaled by the window size w and consistently show the same power law behavior with α = 2.8 (red line), as proven by the data collapse. Inset, Distributions Pθ for different window sizes (not rescaled). d, Rescaled distribution of δ burst durations for VLPO-lesioned rats over a 24 h period (pooled data). Distributions are rescaled by 〈dδ〉ξ, with ξ = 1, and collapse onto a single function following a Weibull behavior f(d; λ, β) (black line) with λ = 15.20 and β = 0.74. Inset, Distributions Pδ for different window sizes (not rescaled). Results in all panels are obtained for fixed threshold Th = 1 on the ratio Rθδ (Fig. 1). Results are consistent when considering separately light and dark periods (Figs. 8, 9).

θ and δ burst detection and definition.

The ratio Rθδ = Sθ/Sδ between θ and δ power is calculated in each window k, with k = 1,2, …, N, and a time series Rθδ(k) is obtained. Given a threshold Th ≥ 1, a θ-burst is defined as a sequence of n consecutive windows where Rθδ > Th, while a δ-burst consists in a sequence of n consecutive windows where Rθδ < 1/Th (Fig. 1). The duration of a burst is given by d = n · w. Durations of θ (δ) bursts are denoted by dθ (dδ). The threshold Th is set equal to 1 throughout the analysis. Results are independent of Th, as shown in Figures 4, 5, and 6, and extensively discussed in the main text.

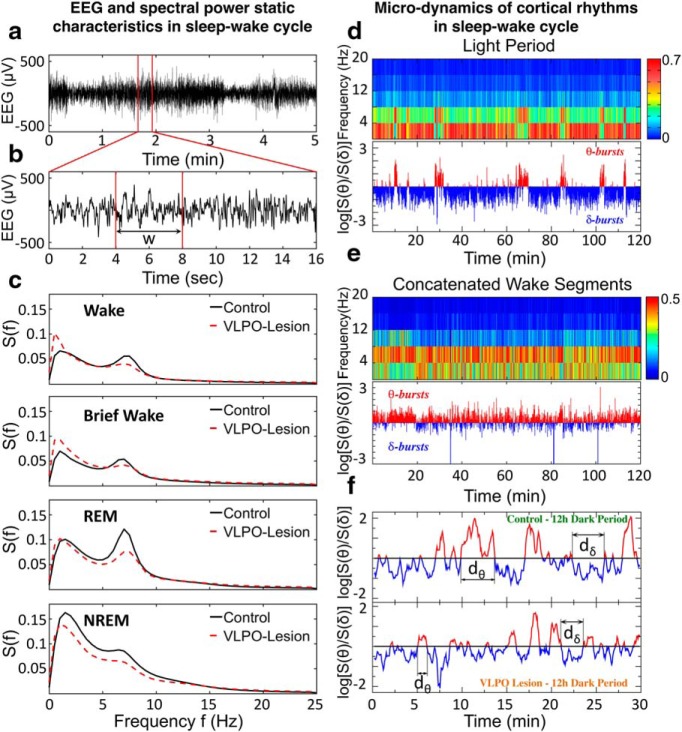

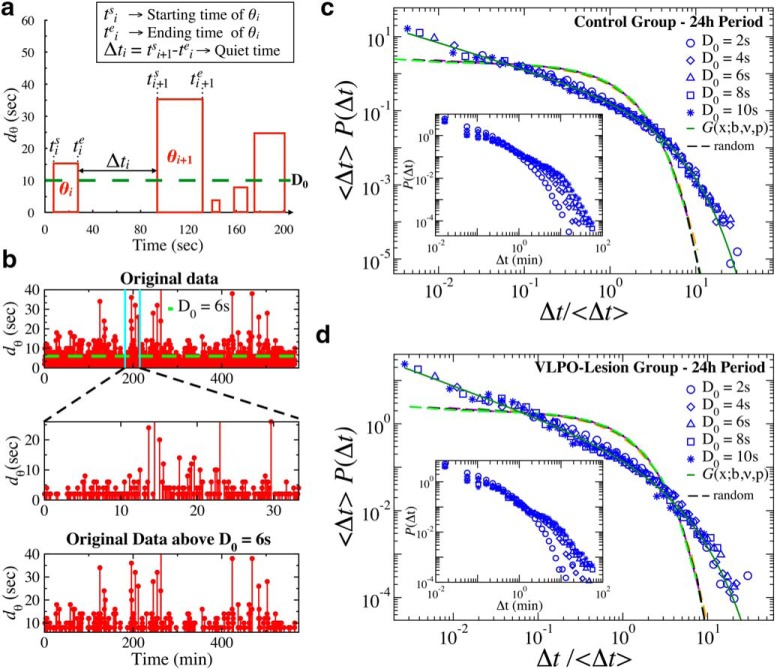

Figure 1.

Cortical activity across the sleep–wake cycle is characterized by intermittent transitions between distinct dominant brain rhythms. a, Representative 5 min EEG trace for a control rat during a 12 h dark period. b, A 16 s segment from the 5 min EEG trace shown in a. The time evolution of the EEG signal is analyzed by evaluating the spectral power in several frequency bands on non-overlapping windows of length w, as shown in d–f. c, Average power spectra for control and VLPO-lesioned rats during Wake, brief wake periods (<1 min), REM, and NREM sleep. d, Top, Spectrogram obtained from cortical EEG signal of a control rat over a 2 h segment of 12 h lights-on period. Spectral power is calculated in non-overlapping time windows w = 4 s, and is color coded over a range (0–20 Hz) of physiologically-relevant frequencies. Segments in red indicate bursts of prominent activity in the low-frequency band (0- 4 Hz, corresponding to δ waves) and in the intermediate frequency band (4–8 Hz, corresponding to θ waves). Bottom, Ratio Rθδ = S(θ)/S(δ) of the spectral power in the θ and δ band in logarithmic scale obtained from the spectrogram at the top. Values Rθδ above log(Th) = 0 (Th = 1) indicate predominance of θ rhythm (red), whereas values below log(Th) = 0 correspond to predominance of δ rhythm (blue). e, Top, Spectrogram obtained from cortical EEG signal over 2 h of concatenated wake segments. Spectral power is calculated in non-overlapping time windows w = 4 s, and is color coded as in explained in d. Segments in red, indicating bursts of prominent activity, are mostly concentrated in the θ band (4–8 Hz). Bottom, Ratio Rθδ of the spectral power in θ and δ band in logarithmic scale obtained from the spectrogram at the top. Values Rθδ above log(Th) = 0 (Th = 1) indicate predominance of θ rhythm (red), whereas values below log(Th) = 0 correspond to predominance of δ rhythm (blue). The ratio Rθδ is almost always larger than 1, indicating that wake periods are dominated by bursting activity in the θ band. f, Smoothed ratio Rθδ of the spectral power in the θ and δ band during 30 min segment of 12 h dark (lights-off) period for a control rat (top) and a VLPO-lesioned rat (bottom). Rθδ is calculated on non-overlapping windows w = 4 s and the smoothing is performed using a 5 point moving average. θ- and δ-bursts are defined as sequences of consecutive windows where either the power in θ or δ band is dominant.

Figure 4.

Critical characteristics in temporal dynamics of bursts in dominant rhythms are a fundamental feature of cortical activity across the sleep–wake cycle, independent of thresholds used to define bursts. The functional form of θ- and δ-burst duration distributions is preserved for different threshold values Th imposed on the ratio Rθδ (Fig. 1). a, Probability distributions of θ-burst durations for control rats over a 24 h period (pooled data) evaluated using different Th values consistently follow the same power law behavior (red line), with a cutoff that is controlled by Th. With increasing Th the distribution cutoff shifts toward shorter burst durations. Inset, Data for different Th collapse onto a single universal function fθ when we plot P(d)dα versus Thϵd, with α = 2.4 and ϵ = 0.8. b, Rescaled distribution of δ-burst durations for control rats over a 24 h period (pooled data) obtained for different Th values collapse onto a single function following a Weibull behavior f(d; λ, β) (black line), with β = 0.71 and λ = 0.11. Distributions are rescaled by 〈dδ〉η, where 〈dδ〉 is the mean δ-burst duration and η = 1.3. Inset, Distributions Pδ for different thresholds (not rescaled). c, Probability distributions of θ burst durations for VLPO-lesioned rats over a 24 h period (pooled data) evaluated using different Th values follow the same power law behavior, with a cutoff controlled by Th. Inset, Data collapse onto a single function fθ by plotting P(d)dα versus Thϵd with α = 2.8 and ϵ = 0.8 (same as for control rats in a). d, Rescaled distribution of δ-burst durations for VLPO-lesioned rats over a 24 h period (pooled data) obtained for different Th values collapse onto a single Weibull distribution f(d; λ, β) (black line) with λ = 0.12 and β = 0.72. Distributions are rescaled by .〈dδ〉η., with η = 1.3. Inset, Distributions Pδ for different thresholds Th (not rescaled). Results in all panels are obtained for a fixed scale of analysis, keeping the window size w = 4 s (Fig. 1). Results are consistent when considering separately light and dark periods (Figs. 5, 6).

Surrogate test for θ- and δ-burst duration distributions.

For each rat, the time series Rθδ(k) is randomly reshuffled to obtain a surrogate Rθδ*(k′). Surrogate θ- and δ-bursts durations (see Fig. 2) are then calculated from Rθδ*(k′) following the procedure illustrated in the previous paragraph. The corresponding θ- and δ-burst duration distributions are shown in Figure 2, insets, together with distributions from original data.

Definition of quiet time Δt.

A quiet time Δt is defined as the time interval between the ending time of a burst tje and the starting time tj+1s of the following one, namely Δtj = tj+1s − tje.

Data binning.

Probability distributions of θ-burst durations are calculated using logarithmic binning, i.e., linear binning in logarithmic scale. Denoting a set of bin boundaries as B = (b1,b2, …, bk) and fixing b1 = 0.03w, the logarithmic bins fulfill the relation bi+1 = bi · 10c, which implies that the bin size is constant in logarithmic scale, i.e., logbi+1 − logbi = c. The following bin size c have been used in this study: Figures 2–9 and 15; c = 0.18. Probability distributions of δ-burst durations are calculated using the following binning procedure. Given a window size w, the bin boundaries e1,e2,…, en, …, ek are obtained using the recursive relation en = e1 + wΣi=2nbi−1, with e1 = 0.5w and n ≥ 2. The following values of the parameter b have been used in this study: Figures 10, b = 1.6; all other figures, b = 1.2.

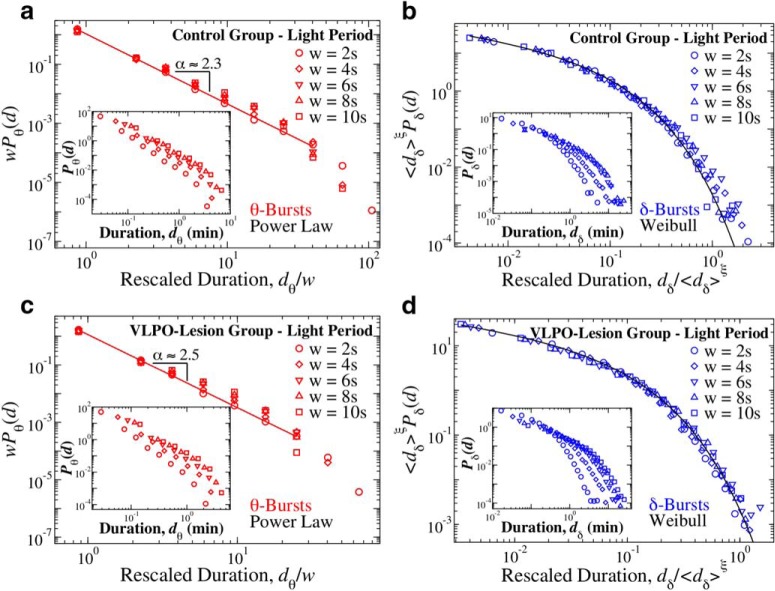

Figure 9.

Distribution of θ- and δ-burst durations in the light period are independent of the scale of analysis and can be described by unique scaling functions. Distribution of θ and δ burst durations in light period for different window sizes w and Th = 1 on the ratio Rθδ. a, Rescaled distribution of θ burst durations for control rats over a 12 h light period (pooled data). Distributions are rescaled by the window size w and consistently show the same power law behavior with α = 2.3, as proven by the data collapse. Inset, Distributions Pθ for different window sizes (not rescaled). b, Rescaled distribution of δ burst durations for control rats over a 12 h light period (pooled data). Distributions are rescaled by 〈dδ〉ξ, with 〈dδ〉 mean δ-burst duration and ξ = 1, and collapse onto a single function fδ that is well described by a Weibull distribution f(x; λ, β) (thick black line), with λ = 0.04 and β = 0.70. Inset, Distributions Pδ for different window sizes (not rescaled). c, Rescaled distribution of θ burst durations for VLPO lesioned rats over a 12 h light period (pooled data). Distributions are rescaled by the window size w and consistently show the same power law behavior with α = 2.5, as proven by the data collapse. Inset, Distributions Pθ for different window sizes (not rescaled). d, Rescaled distribution of δ burst durations for VLPO-lesion rats over a 12 h light period (pooled data). Distributions are rescaled by 〈dδ〉ξ, with ξ = 1, and collapse onto a single function fδ that is well described by a Weibull distribution f(x; λ, β) (thick black line), with λ = 0.04 and β = 0.67. Inset, Distributions Pδ for different window sizes (not rescaled).

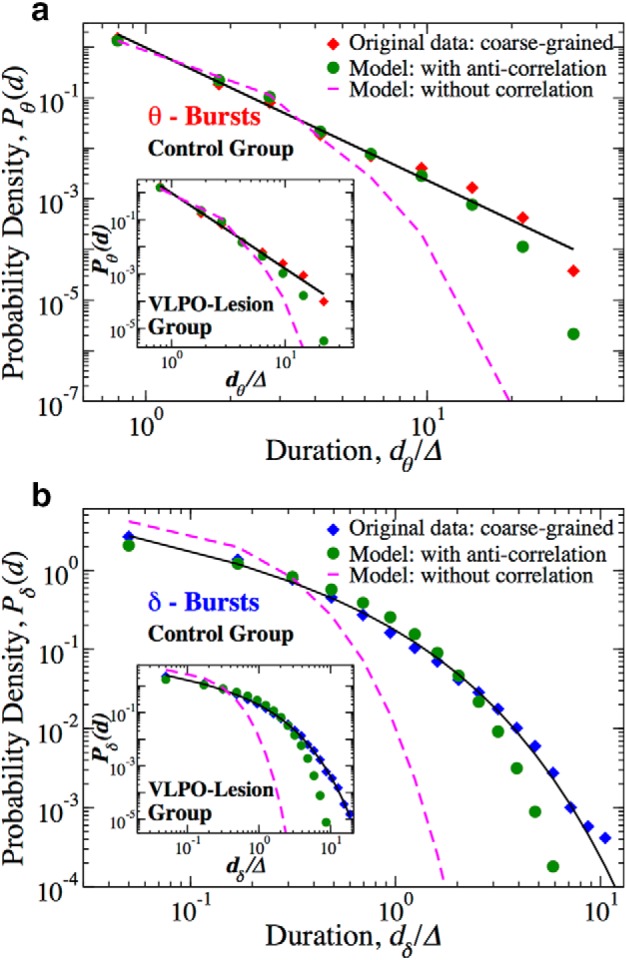

Figure 15.

Anti-correlations between consecutive θ- and δ-bursts durations are essential for emerging duality of power-law and Weibull dynamics. Probability distributions of θ- and δ-burst durations from 24 h control and VLPO-lesioned rat data coarse-grained (CG) over a window Δ = 10 s, are compared with the distributions obtained from the model-generated coarse-grained binary time series of θ- and δ-bursts durations with anti-correlations and without correlations (random pairing of θ- and δ-bursts; Fig. 14). a, Distributions Pθ(d) of θ-burst durations for: (1) 24 h control rats data (red diamonds), (2) model-generated time series of θ- and δ-bursts durations with anti-correlations (green circles), and (3) model-generated time series with random pairing of θ- and δ-bursts durations (magenta dashed line). Inset, Results from same analysis on Pθ(d) for the group of VLPO-lesioned rats. b, Distribution Pδ(d) of δ-burst durations for: (1) 24 h control rats data (blue diamonds), (2) model-generated time series with anti-correlations (green circles), and (3) model-generated time series with random pairing of θ- and δ-bursts durations (magenta dashed line). Inset, Results from same analysis on Pδ(d) for the group of VLPO-lesioned rats. In both a and b, durations are in units of Δ, which is the window size used to coarse grain the sequences of θ- and δ-bursts durations. The distributions obtained from the model using anti-correlated dθ and dδ pairing (green circles) closely match the duration distributions for the original data (diamonds), power-law for Pθ(d) and Weibull for Pδ(d), for both control and VLPO-lesioned rats. In contrast, a random pairing of dθ and dδ produces duration distributions following the Poisson functional form (magenta dashed lines) that significantly deviates from the original data.

Figure 10.

Hierarchical self-similar structure in quiet times between consecutive θ-bursts indicates coupling between time of occurrence and burst duration. a, Schematic diagram of quiet times Δt between consecutive θ-bursts. A quiet time Δti is the time elapsed from the end of burst θi to the beginning of the following burst θi+1. b, Top, Time series of θ-burst durations for ∼600 min recording of a control rat. Middle, A 40 min segment from the sequence shown at the top. Bottom, Sequence comprised only of the θ-burst durations longer than D0 = 6 s that are present in the 600 min time series shown at the top. Selecting only bursts longer than D0 = 6 s, the temporal pattern at the scale of 600 min looks similar to the pattern at smaller scale of 60 min, indicating hierarchical self-similar structure in the quiet times. c, Distribution of quiet times for different thresholds D0 on θ-burst durations over a 24 h period in control rats (blue symbols). When rescaled by 〈Δt〉 (main panel), distributions obtained for different D0 collapse onto a unique function that is well described by a generalized Gamma distribution G(x; b, v, p) (solid green line), with b = 2.03, ν = 0.30, and p = 0.81. Applying the same procedure to a sequence of randomly reshuffled θ-burst durations leads to distributions that collapse onto an exponential function (dashed lines). Inset, Distributions of quiet times for different thresholds D0 before rescaling. d, Distributions of quiet times for different thresholds D0 on θ-burst durations over a 24 h period in VLPO-lesioned rats. Distributions collapse onto a unique function when rescaled by 〈Δt〉 (main panel). Similar to control rats, this function is well described by a generalized Gamma function G(x; b, v, p) (solid green line), with b = 1.55, ν = 0.28, and p = 0.70. Distribution of quiet times obtained from a sequence of randomly reshuffled θ-burst durations collapse onto an exponential distribution (dashed lines). Insets, Distributions of quiet times in VLPO-lesioned rats for different thresholds D0 before rescaling. Results are consistent when considering separately light and dark periods.

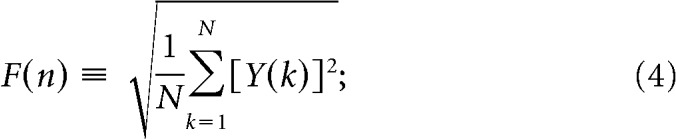

Duration distributions: error bars.

An error δP is associated to each bin of the distribution for pooled data presented in Figures 2 and 3. The number of data n in a particular interval [D,D + dD] can be considered as given by the binomial distribution, given that the total number of data N is much larger than the range of correlations. Therefore, the associated SD is σ = . Because P(D) = n/(NdD), the error on P(D) is given by the following:

|

where p = P(D)dD is the probability to observe a duration D in the range [D,D + dD] and N is the total number of bursts and dD is the corresponding bin size. Power-law fits for θ-burst duration distributions shown in Figures 2 and 3 are performed on the pooled data. Estimates are reported in the corresponding figure captions together with associated errors on the fit.

Spearman's correlation.

Given to variables X and Y, the Spearman's correlation coefficient is defined as follows:

|

where rgX and rgY are the tied rankings of X and Y, respectively, σrgX and σrgY their SDs, and cov (rgX, rgY) indicates the covariance between rgX and rgY.

Surrogate test for correlations between consecutive θ- and δ-burst duration.

To test significance of correlations between consecutive θ- and δ-burst durations, a surrogate sequence of burst durations is generated for each rat by randomly reshuffling the original order of θ- and δ-bursts. The Spearman's correlation coefficient ρs between consecutive θ- and δ-bursts is calculated for each surrogate. The average Spearman's correlation coefficient obtained from all surrogates is then compared with the average correlation coefficient calculated from the original sequences of burst durations via t test (see Results; Fig. 12). Correlation coefficients for surrogate data for both control and VLPO-lesioned rats during dark, light, and 24 h are all with value |ρs| < 103.

DFA.

The DFA is a method based on random walk (Peng et al., 1994). It improves the classical fluctuation analysis (FA) for nonstationary signals where embedded polynomial trends mask the intrinsic correlation properties in the fluctuations (Peng et al., 1994). The performance of DFA for signals with different types of non-stationarities and artifacts has been extensively studied and compared with other methods of correlation analysis (Taqqu et al., 1995; Hu et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2005). The DFA method is briefly described by the following steps (Peng et al., 1994):

A given signal ui (i = 1, …, N, where N is the length of the signal) is integrated to obtain y(k) ≡ Σi=1k[u(i) − 〈u〉], where 〈u〉 is the mean of ui;

The integrated signal y(k) is divided into boxes of equal length n;

In each box of length n we fit y(k) using a first-order polynomial function, which represents the trend in that box. The y-coordinate of the fit curve in each box is denoted by yn(k);

- The integrated profile y(k) is detrended by subtracting the local trend yn(k) in each box of length n:

- For a given box length n, calculate the root mean square (rms) fluctuation function for this integrated and detrended signal:

Repeat the above computation over a broad range of box lengths n, where n represents a specific space or time scale, to obtain a functional relationship between F(n) and n.

For a power-law correlated time series, the average rms fluctuation function F(n) and the box size n are connected by a power-law relation, that is F(n) ∼ nαd. The exponent αd is a parameter that quantifies the long-range power-law correlation properties of the signal. Values of αd < 0.5 indicate the presence of anti-correlations in the time series, αd = 0.5 absence of correlations (white noise) and αd > 0.5 indicates the presence of positive correlations in the time series.

Conditional probabilities analysis.

The conditional probability of an event H for a given event X is defined as follows:

|

where P(H ∩ X) is the probability that H and X jointly occur, and P(X) > 0 is the probability of the event X. The condition X reduces the statistics and increases the fluctuations of the distribution P(H|X) compared with P(H). The following error is associated to each bin of the densities (Corral, 2006): ϵH = , where p = P(H)dH is the probability to observe a H in the range H,H + dH and N is the total number of events. From probability theory P(H|X) = P(X) if and only if H does not depend on X. On the contrary, P(H|X) ≠ P(X) implies that H and X are not independent of each other, and their relation can be quantified by a suitable correlation measure. In the analysis of burst coupling (see Results, Anti-correlated coupling between the durations of consecutive θ and δ-bursts), H and X are considered significantly correlated if P(H|X) − P(X) > ϵH.

Software accessibility.

Software used for data preprocessing is available upon request.

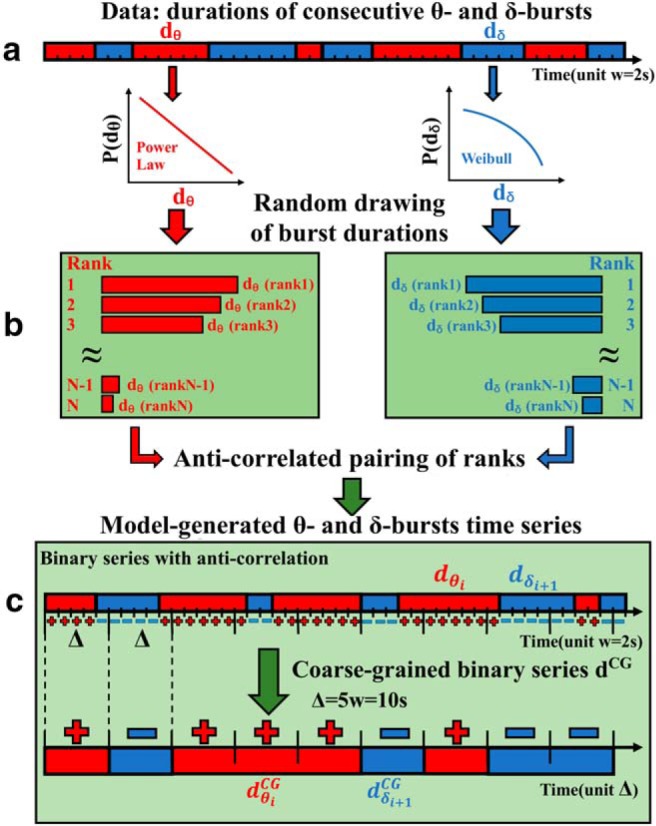

Model of anti-correlated burst coupling

The model consists of the following steps.

Random drawing and ranking.

N durations dθ and dδ are randomly drawn from the empirical distributions previously obtained using a specific window size w. dθ and dδ are separately sorted in ascending order, i.e., from shortest to longest, and get a distinct ordinal numbers from k = 1,2, …, N, which corresponds to their rank. This procedure ensures that each duration has a unique rank. The ranked dθ and dδ are then paired with a tunable degree of anti-correlation and a new time series of alternating θ- and δ-burst durations is thus generated. The coarse-grained properties of the resulting time series depends on the degree of anti-correlations used in the pairing.

Correlated pairing.

Once dθ and dδ are ranked and a distinct, unique ordinal number is associated to them, one randomly choose a dθ with rank k1 between 1 and N. To choose the following dδ, one draws a random number k2 from a Gaussian distribution with mean μ = 1 + N − k1 and SD σ, and takes dδ as the duration corresponding to rank k2. This procedure is iterated N times, and at each iteration i the mean of the Gaussian from which one draws the next random rank, ki, depends on ki−1, i.e., μ − 1 + N − ki−1. At each iteration, ki will correspond to a duration dδ from the sorted δ-burst durations if the preceding burst was a θ-burst with duration dθ, whereas ki will select a duration dθ from the sorted θ-burst durations if the preceding burst was a δ-burst with duration dδ. As a result one obtains a sequence of dθ and dδ whose degree of anti-correlations is controlled by a single parameter, σ. The smaller σ, the stronger anti-correlations are.

Binary series and coarse-graining.

To characterize the coarse-grained properties, the time series is first converted in a binary sequence, namely a sequence of “+” and “−”. Because each duration is by definition a multiple n of the unit window w, namely d = nw, the n windows belonging to a dθ are populated with +, whereas the n windows belonging to a dδ with − (see Fig. 14c). As a result one has a sequence of windows populated with + and −. This binary sequence is then coarse-grained grouping a given number Δ of consecutive windows, with Δ odd number, and assigning + or − to the new windows of size Δ according to a majority rule, i.e., one assign + (−) if the number of + is larger (smaller) than the number of − (see Fig. 14). A coarse-grained binary sequence (CGBS) is thus obtained, and dCG coarse-grained durations are calculated as shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Schematic diagram of a phenomenological model to generate sequences of θ- and δ-burst durations with varied degree of anti-correlated coupling. a, First, burst durations dθ and dδ are randomly drawn from the empirically obtained distributions (power-law and Weibull; Fig. 4) and separately ranked. Durations d = n * w are a multiple of the scale of analysis (window size w = 2 s). b, Ranks of θ- and δ-burst durations are then paired to form an anti-correlated sequence: if the rank(dθ) of a θ-burst is large, then the rank(dδ) of the following dδ-burst is selected to be smaller, and vice versa. Repeating this process leads to a sequence of generated dθ and dδ durations with a certain degree of anti-correlation. c, This newly generated anti-correlated time series is binarized, i.e., +/− is assigned to each window w that belongs either to a dθ (red, +) or dδ (blue, −) duration, respectively. The binary time series is then coarse grained according to a majority rule applied over a window Δ = 5w. From the resulting CGBS, consecutive θ durations, dθCG, and δ durations, dδCG, are extracted.

Results

Transient dynamics in bursting activity of θ and δ rhythms

Statistics of sleep and wake bout durations show that control rats spend on average 50.47 ± 3.37% of the time in wakefulness, 42.12 ± 2.39% in NREM sleep, and 7.41 ± 1.09% in REM sleep in the 24 h period. Correspondingly, rats with VLPO lesion spend on average more time in wakefulness (61.46 ± 4.17%), and experience a corresponding decrease in the percentage of NREM (31.94 ± 3.85%) and REM sleep (6.60 ± 0.86%) across the 24 h period, in agreement with previous reports (Lu et al., 2000; Vetrivelan et al., 2012). The analysis of power spectra (Fig. 1c) for control rats indicates dominant delta rhythm in NREM and increasing spectral power in the theta band for REM and WAKE, and a decrease in relative delta power during NREM in VLPO-lesioned rats (Lu et al., 2000; Vetrivelan et al., 2012). However, total sleep–wake time, average bout duration, and spectral power reflect static characteristics of the sleep process. In contrast, to investigate emergent signatures of criticality in sleep micro-architecture, we focus on dynamical characteristics of dominant cortical rhythms at short time scales.

To dissect the temporal organization of δ and θ-bursts in the broadband brain activity across the sleep–wake cycle, we analyze the time evolution of the EEG signal by evaluating the spectral power in several frequency bands on non-overlapping windows of length w (Fig. 1a,b; see Materials and Methods, Data analysis). Figure 1d shows a typical spectrogram S(f) as a function of time for a 2 h lights-on recording of a rat in the control group. In each window, the spectral power is primarily concentrated in either the δ-wave (0–4 Hz) or the θ-wave (4–8 Hz) band, and exhibits sharp transitions from periods with dominant δ to periods with dominant θ waves. In particular, during wake periods most of the windows in the spectrogram exhibit dominant θ band (Fig. 1e), with fewer transitions to periods with dominant δ waves. Such dynamics can be understood as the temporal evolution of the ratio Rθδ = S(θ)/S(δ) between θ and δ spectral power in association with different physiological states; NREM, REM, and arousals/wake (Fig. 1 shows the transient dynamics of δ- and θ-wave power represented by the logarithm of Rθδ as a function of time t).

The ratio Rθδ(t) exhibits irregular, intermittent fluctuations between values larger and smaller than a threshold Th, a typical characteristic of non-equilibrium dynamics: Rθδ > Th = 1 indicates that the spectral power in the θ-wave band is dominant; vice versa, for Rθδ < Th = 1 the spectral power is dominated by the δ-wave (Fig. 1d,e). We define bursts in θ and δ rhythms as sequences of consecutive time windows where Rθδ > Th = 1 and Rθδ < Th = 1, respectively (Fig. 1f). We associate a duration d = n × w to each burst (see Materials and Methods, Data analysis), where n is the number of consecutive windows belonging to a given burst and w is the window length (Fig. 1f).

Distinct functional forms of θ- and δ-burst duration distributions indicative of self-organization at criticality

We next study the probability distribution of the durations of θ- and δ-bursts over a 24 h period for control and VLPO-lesioned rats (see Materials and Methods, Experimental setup). We notice that θ- and δ-bursts follow very different statistics. The distribution Pθ of θ-burst durations exhibits power-law behavior followed by a cutoff (Fig. 2a), Pθ(d) ∝ d−α, where α denotes the scaling exponent of the power-law. Power law distributions P(x) ∝ x−α are the statistical hallmark of scale invariance, i.e., they are not altered by a change of scale from x to Lx, and depending on the context, they imply that events of any size, length, or duration are likely to occur with some finite probability that is larger than expected in a random or short-range correlated process. Presence of power-law indicates absence of characteristic time scales in the underlying dynamics, which is a typical feature of physical systems at the critical point of continuous phase transition; a highly sensitive state where cooperative behavior spontaneously emerges over a range of time scales characterized by long-range correlations. Importantly, the scale-invariant power-law behavior characterizing the distribution of θ-burst durations is significantly influenced by lesions in the VLPO. Indeed, we find that α ≃ 2.4 in control rats, whereas α ≃ 2.8 in VLPO-lesioned rats (Fig. 2a). The power-law is consistent across rats in both groups, and the average exponent in the VLPO-lesioned group is significantly higher than the exponent in the control group [αCTRL = 2.29 ± 0.15 and αVLPO = 2.71 ± 0.11 (mean ± SD); t test, p = 0.0005]. An increase in the power-law exponent indicates that bilateral lesions of the VLPO alter the dynamical micro-architecture of θ-bursts across the 24 h sleep–wake cycle, leading to a decreased likelihood of long lasting θ-bursts; an effect not previously observed.

In contrast to the power-law feature of θ-burst, the statistics of δ-burst duration follows a different behavior that is described by a Weibull distribution Pδ(d; λ, β) = e−(d/λ)β, where λ indicates the characteristic time scale, and β is the shape parameter (Fig. 2b). Further, we find that the distribution of δ-burst durations follows the same Weibull functional form for both control and VLPO-lesioned groups, with similar values of the parameters λ and β.

The functional forms established for the distributions of θ- and δ-burst durations in Figure 2, indicate a very different temporal organization of θ- and δ-bursts. A surrogate test based on randomizing the sequence of windows w in the EEG spectrogram (Fig. 1d) leads to exponentially distributed θ- and δ-burst (Fig. 2, insets), and shows that the observed temporal organization in bursting activity of brain rhythms is physiologically relevant and relates to underlying regulation.

The results demonstrate a remarkable duality of scale-free, power-law dynamics for θ-bursts, and Weibull dynamics with characteristic time scale for δ-bursts. The coexistence of scale-free θ-bursts and Weibull distributed δ-bursts appears to be a general feature of cortical activity across the entire sleep–wake cycle of individual subjects in each group, and it is preserved after major lesions of the VLPO area. Remarkably, VLPO lesions, although significantly affecting sleep statistics (Lu et al., 2000; Vetrivelan et al., 2012), do not disrupt the fundamental duality of power-law and Weibull. Coexistence of scale-invariant and exponential-like behaviors is a hallmark of self-organization at criticality in non-equilibrium systems characterized by alternating active and inactive states; unlike systems at equilibrium, such systems maintain critical behavior without external tuning (Boffetta et al., 1999; Paczuski et al., 2005; Munoz, 2018). Thus, our observations point to an intrinsic common mechanism that underlies the temporal organization of bursting activity in both δ and θ cortical waves across the distinct physiological states of wake/arousals and sleep. Importantly, the deviation of the VLPO-lesioned θ-burst power-law exponent from the value measured in control rats, indicates that lesion of VLPO neurons alters the optimal underlying dynamics for sleep regulation.

To better describe bursting activity of θ- and δ-waves across the sleep–wake cycle, and the role of the VLPO neuronal population in this dynamics, we next analyze the distributions of θ and δ-burst durations separately during the 12 h dark/light periods. Although sleep and wake are characterized by different dominant brain rhythms with distinct dynamics, synchronization and coupling patterns across cortical areas (Kopell et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2015), our analysis shows that the duality of power-law and Weibull for θ- and δ-bursts duration distributions is robust and independent of the dominant physiologic state. Indeed, such coexistence appears to be a basic characteristic of cortical activity during both dark and light periods (Fig. 3). Importantly, the scaling exponent α of the power-law as well as the Weibull parameters λ and β concurrently change comparing dark to light periods, indicating a coordinated modulation of θ and δ wave dynamics across sleep and wake. In contrast to humans, rats are predominantly awake during the dark period and asleep during the light period. We observe that α is larger in the dark than in the light period (Fig. 3a,c), indicating that long θ-bursts are more likely when rats are predominantly asleep. The higher probability of longer-lasting θ-bursts during the light period could be associated with the presence of longer episodes of REM sleep, when θ-waves are dominant. This leads to an average increase of the power in the θ band and thus to a higher likelihood for longer θ-bursts during the light periods. For control rats, we find that the power-law exponent decreases from α ≈ 2.65 during dark to α ≈ 2.5 during light (Fig. 3a). This variation is more pronounced in VLPO-lesioned rats, where the exponent decreases from α ≈ 3.1 during dark to α ≈ 2.5 during light periods (Fig. 3c), and may be related to the average reduction of REM sleep. These results are consistent across rats both during dark [αCTRL = 2.62 ± 0.18; αVLPO = 3.10 ± 0.24 (mean ± SD); t test, p = 0.003] and light [αCTRL = 2.14 ± 0.13; αVLPO = 2.29 ± 0.15 (mean ± SD); t test, p = 0.131], and show significant difference particularly for the 12 h dark period. Paired tests also show significant differences between dark and light periods in each group (Control dark vs control light t test, p = 0.0005; VLPO dark vs VLPO light t test, p = 0.0010). The comparison between control and VLPO-lesioned rats shows that VLPO lesions affect the distributions of θ-burst durations, in particular during the dark period, while having no particular influence on the distributions of δ-burst durations, which overlap within error bars (Fig. 3). This indicates that, although lesions of VLPO neurons reduce δ power and total sleep time (Lu et al., 2000; Vetrivelan et al., 2012), they do not alter the dynamics of δ-bursts, but instead influence the power-law organization in θ-burst dynamics and lead to an increase of the power-law exponent, indicating a decreased likelihood for long-lasting bursts and a higher probability to observe shorter bursts; evidence of fragmentation of bursting activity in the θ-wave band that parallels the increased fragmentation of sleep in VLPO-lesioned rats.

Previous studies have shown that preceding sleep–wake history affects sleep consolidation and slow-wave activity. In particular, sleep deprivation increases sleep consolidation and continuity, reduces frequency of short wake episodes, and thus sleep fragmentation (Trachsel et al., 1991). Moreover, it has been shown that after long periods of sleep deprivation NREM episodes tend to be longer, with a larger amount of slow-wave sleep and increased EEG amplitude (Tobler and Borbély, 1986; Franken et al., 1991; Rodriguez et al., 2016). In this context, it would be important to understand how change in homeostatic drive (for example in response to sleep deprivation) would impact the reported underlying critical dynamics of cortical rhythms. While the established non-equilibrium dynamics in cortical rhythms at small time scales apparently contrast homeostatic regulation of the sleep–wake cycle (Borbély and Achermann, 1999; Achermann and Borbély, 2003), the interplay between this two mechanisms remains to be better investigated and understood in future studies. VLPO-lesioned rats, although exhibiting an increase in the percentage of wake across the 24 h period and in average duration of wake bouts (Lu et al., 2000; Vetrivelan et al., 2012), do not show extended periods of wake comparable to those used in previous experimental protocol for studying sleep deprivation (Tobler and Borbély, 1986; Franken et al., 1991; Trachsel et al., 1991), and therefore we cannot not draw any conclusion on the effect of homeostatic mechanisms on the underlying critical dynamics based on the data analyzed here.

Furthermore, loss of VLPO neurons also disinhibit the wake-promoting system including hypocretin system, and leads to their increased activity (Lu et al., 2000; Vetrivelan et al., 2012). These changes are interrelated, and may be difficult to dissociate from each other. For example, changes in EEG spectra (Fig. 1) and sleep fragmentation after VLPO lesions (Lu et al., 2000; Vetrivelan et al., 2012) could also be due to increased activity of hypocretin system (Sakurai, 2007). On the other hand, other manipulations, e.g., water/food availability, LD conditions, ambient temperature etc., could also alter EEG and sleep–wake cycle by altering VLPO neuron activity, and therefore influence the θ- and δ-burst dynamics. Our current study investigated the intrinsic properties of cortical dynamics following specific VLPO lesions, and future investigations are necessary to understand the mechanisms (changes in VLPO neural activity) by which other manipulations alter cortical dynamics, and in particular affect the ability of the system to self-tune at criticality.

Robust scale-invariant critical behavior of θ- and δ-bursts across time scales

We have shown that bursts associated with θ and δ rhythms exhibit a distinct temporal organization that is captured by specific duration distributions: a power-law for θ-bursts, indicating absence of a characteristic time scale, and a Weibull for δ-bursts, with a characteristic time scale λ (Figs. 2, 3). These findings are based on a particular observational window size w and threshold Th that were used to analyze bursting activity (Fig. 1; see Materials and Methods, Data analysis). To demonstrate that our results are independent of the particular choice of Th and w, we repeat the analyses for a range of parameter values. We find that the dynamics of burst durations across the 24 h sleep–wake cycle is indeed described by unique scaling functions.

We first examine the duration distributions of θ- and δ-bursts for different threshold values Th, keeping the window size w fixed. By increasing the threshold on the ratio Rθδ from Th = 1 to Th = 2, we find that the scaling exponent α characterizing the power-law distribution of θ-burst durations remains stable (data collapse onto a single curve; Fig. 4a,c). The scaling behavior is followed by a cutoff that, with increasing Th values, shifts to shorter burst durations dθ. For both control and VLPO-lesioned rats this behavior can be expressed in terms of the following scaling relation:

Where α is the power-law scaling exponent, f(d/Th−ϵ) is a scaling function, and ϵ expresses the dependence of the cutoff on Th. The existence of a scaling function f(d/Th−ϵ) satisfying Equation 6 is confirmed by the data collapse obtained by plotting P(d)dα versus Thϵd for several values of Th (Fig. 4a,c, insets).

Similarly, we show that the distribution of δ-burst durations is independent of the threshold Th, and is described by a single scaling function (Fig. 4b,d). Because a δ-burst is defined as a time period of consecutive windows w where Rθδ < Th = 1 (Fig. 1f), to properly explore the behavior of the duration distribution for states with increasingly dominant δ power, we repeat the analysis for different values Th < 1. We observe that, as Th decreases, the probability for long δ-bursts decreases, while short δ-bursts become more likely (Fig. 4b,d, insets). However, when distributions are rescaled by their respective mean δ-burst duration 〈dδ〉, they all collapse onto a unique function fδ, which is the same for both control and VLPO-lesioned rats (Fig. 4b,d, respectively). Such function is defined by the following scaling relation:

where η = 1.3 for both rat groups, and is well described by a Weibull functional form, as found by rescaling dδ and Pδ (Fig. 4b,d).

Repeating the analysis for 12 h dark/light periods separately, we find that Equations 6 and 7 consistently describe the dynamics of δ- and θ-bursts in both control and VLPO-lesioned groups (Figs. 5, 6).

Thus, our results indicate that the duality of power-law and Weibull behavior, as well as the scaling properties summarized in Equations 6 and 7, are robust features of the bursting activity across the sleep–wake cycle, and do not depend on the particular threshold Th used to study the dynamics of θ- and δ-bursts.

Furthermore, we find that the functional behavior of the distribution of θ- and δ-burst durations is to a large extent also independent of the window size w, used to investigate the time course of the EEG spectral power. Intuitively, a larger w would tend to fail in identifying short bursts and merge them together, thus causing an increase in the probability of observing longer durations. In that regard, considering the power-law temporal organization of θ-bursts, larger window sizes w mainly influence the tail of the distribution with longer durations, thus leading to a decrease of the scaling exponent α (Fig. 7a,c, insets). We note that the window size effect becomes visible only for extremely large w compared with the average θ-burst duration 〈dθ〉. However, when the θ-burst durations are rescaled by the window size w, all distributions collapse onto a single power-law (Fig. 7a,c), confirming the robustness of the results obtained in Figure 2a for both control and VLPO-lesioned rats. Such rescaling is defined by the following relation:

Separate analyses of 12 h dark/light periods for different window sizes w (Figs. 8a,c, Fig. 9a,c) further confirm the robustness of the established power-law behavior for the θ-burst durations (Fig. 3a,c).

Figure 8.

Distribution of θ- and δ-burst durations in the dark period are independent of the scale of analysis and can be described by unique scaling functions. Distribution of θ and δ burst durations in dark period for different window sizes w and Th = 1 on the ratio Rθδ. a, Rescaled distribution of θ burst durations for control rats over a 12 h dark period (pooled data). Distributions are rescaled by the window size w and consistently show the same power law behavior with α = 2.65, as proven by the data collapse. Inset, Distributions Pθ for different window sizes (not rescaled). b, Rescaled distribution of δ burst durations for control rats over a 12 h dark period (pooled data). Distributions are rescaled by 〈dδ〉ξ, with 〈dδ〉 mean δ-burst duration and ξ = 1, and collapse onto a signle function fδ that is well described by a Weibull distribution f(x; λ, β) (black line), with β = 0.66 and λ = 0.04. Inset, Distributions Pδ for different window sizes (not rescaled). c, Rescaled distribution of θ burst durations for VLPO lesioned rats over a 12 h dark period (pooled data). Distributions are rescaled by the window size w and consistently show the same power law behavior with α = 3.1, as proven by the data collapse. Inset, Distributions Pθ for different window sizes (not rescaled). d, Rescaled distribution of δ burst durations for VLPO-lesion rats over a 12 h dark period (pooled data). Distributions are rescaled by 〈dδ〉ξ, and collapse onto a single function that is well fitted by a Weibull distribution f(x; λ, β) (black line), with β = 0.70 and λ = 0.05. Inset, Distributions Pδ for different window sizes (not rescaled).

A similar data collapse characterizes the dependence of the δ-burst duration distribution on window size w. Generally, we observe that for increasing w the probability for long δ-bursts increases, while short δ-bursts become less likely (Fig. 7b,d, insets). When δ-burst duration distributions corresponding to different window sizes w are rescaled by their respective mean duration 〈dδ〉, we find that all distributions collapse onto a unique function fδ following a Weibull behavior (Fig. 7b,d) and obeying the scaling relation as follows:

As in the case of θ-burst dynamics, the temporal organization of δ-bursts is robust and characterized by a scaling function (Eq. 9), which is universal for the control and VLPO groups, and remains stable during light and dark periods (Figs. 8b,d, 9b,d).

The existence of universal scaling functions (Eqs. 6–9) not only demonstrates that duration distributions are independent of the specific set of parameters used to identify θ- and δ-bursts, but also constitutes evidence of scale invariance, a property associated with systems operating at criticality.

Hierarchical micro-architecture in the temporal order of quiet (δ-bursts) and active (θ-bursts) states in the sleep–wake cycle

The results reported in the previous sections show a remarkable coexistence of scale-invariant power-law structure for the durations of θ-bursts and a Weibull functional form with a characteristic time scale for δ-burst durations (Figs. 2,3). This evidence draws a strong parallel with far-from-equilibrium phenomena that are characterized by bursting dynamics and abrupt transitions between active and quiet states, such as avalanches and earthquakes (Boffetta et al., 1999; Corral, 2004; Paczuski et al., 2005; Munoz, 2018). For instance, the intensity of avalanches and earthquakes (active states) is also described by power-law distributions, while time intervals between consecutive avalanches/earthquakes (quiet states) follow a generalized Gamma distribution with a characteristic time scale (exponential tail). In this context Gamma is a universal scaling function that is independent of spatial scales and minimum magnitude thresholds, and is consistently observed for a broad range of conditions despite the large variability associated with phenomena such as avalanches and earthquakes (Corral, 2004; Ribeiro et al., 2010; de Arcangelis et al., 2016).

In sleep dynamics, wake and brief arousals during sleep can be considered as active states that, in rodents, are characterized by bursts in θ rhythms. Hence, we hypothesize that a hierarchical structure, invariant across time scales, may underlie the occurrence of θ-bursts, in analogy with non-equilibrium critical phenomena, and investigate the relationship between the duration of θ-bursts and their temporal occurrence (Fig. 10). To this end, we consider the time sequence of θ-bursts, and we study the statistical features of the quiet times Δt separating consecutive bursts, taking into account the duration dθ of each θ-burst (Fig. 10a). Because θ-bursts vary in duration, we impose a threshold D0 representing the time scale of analysis, and we define the quiet time Δti as the period from the end of θi-burst to the beginning θi+1-burst. Thus, the statistical characteristics of Δti depend on the threshold value D0. We then obtain the probability distribution P(Δt; D0) of quiet times Δti for different values of D0 (Fig. 6c,d, insets). With increasing threshold (scale of observation) D0, the probability of longer Δti increases, whereas the probability of short Δti decreases, leading to different curves for the distributions P(Δt; D0).

Visual inspection of the complex profile formed by the time sequence of θ-bursts and their respective durations shows an apparent similarity when comparing short segments of the profile with the entire sequence above a given threshold D0 (Fig. 6b). Presence of statistical self-similarity, observed after effective coarse-graining of the profile, indicates a hierarchical structure across time scales D0 that characterizes θ-bursts occurrence times and durations, and the associated quiet times. To demonstrate statistical self-similarity in the quiet times, we systematically analyze the functional form of the probability distributions P(Δt; D0) for different thresholds D0 by rescaling each distribution by the average quiet time 〈Δt〉D0. Remarkably, we find that all distribution curves collapse onto a single function G (Fig. 6c,d), defined by the following scaling relation:

The scaling relation in Equation 10 represents a mathematical expression of the statistical self-similarity in the profile formed by the quiet times and θ-burst durations shown in Figure 6b. We find that the scaling function G(Δt/〈Δt〉) is well described by the generalized Gamma distribution G(Δt/〈Δt〉; b, v, p) = p/bv(Δt/〈t〉)v−1e−(Δt/b〈t〉)p/Γ(v/p) (Stacy, 1962), where in our analysis Δt/〈Δt〉 is a dimensionless quiet time. The Gamma functional form is homogeneous (Ivanov et al., 1996) i.e., rescaling the variable leaves the functional form unchanged. Such scaling function indicates a hierarchical structure in the quiet times between consecutive θ-bursts, independent of the scale of observation D0. In the limit of D0 = 0, the quiet time distribution P(Δt; D0) coincides with the distribution of δ-burst durations Pδ (Figs. 2b, 3b,d); a Weibull functional form that belongs to the same class of homogeneous functions as the generalized Gamma.

Our analysis shows that the scaling relation in Equation 10 and the associated Gamma functional form for the quiet times are robust: (1) we find them in the 24 h period (Fig. 10) as well as separately during light and dark periods, and (2) they do not significantly change with lesion in the VLPO (Fig. 10, compare c, d). Further, the presence of such hierarchical structure in quiet times indicates specific temporal order in the occurrence of θ-bursts. To explicitly verify this, we randomly reshuffle the sequence of θ-burst durations, while preserving the δ-burst durations corresponding to quiet times at D0 = 0, and we perform the analysis on the reshuffled sequence to obtain quiet time distributions Prand(Δt; D0) for different thresholds D0. In this case, after rescaling the distributions Prand(Δt; D0) by the average quiet time 〈Δt〉D0, their curves collapse onto an exponential distribution (Fig. 10c,d, dashed lines); a hallmark of temporal independence between consecutive events (Daley and Vere-Jones, 1988). This clearly demonstrates that temporal correlations are intimately related to the existence of non-exponential scaling functions (Eq. 10; Daley and Vere-Jones, 1988; Corral, 2004).

Notably, a similar temporal organization characterized by coexistence of power-law and generalized Gamma distribution has been reported for active states and quiet times in a range of non-equilibrium systems self-tuning at criticality (earthquakes, avalanches; Corral, 2004; Pruessner, 2012; Munoz, 2018). Thus, our findings of power-law distribution for θ-burst durations (Figs. 2,3) combined with a generalized Gamma distribution for the quiet times between consecutive θ-bursts at different scales of observation D0 (Fig. 10) are a strong evidence in support of our hypothesis that bursting activity of fundamental brain rhythms and the associated sleep micro-architecture exhibit critical non-equilibrium behavior.

Long-range power-law correlations in the durations of θ and δ bursts

Physical systems at criticality exhibit long-range correlations that span the entire system across space and time scales, and lead to the emergence of collective cooperative behavior (Stanley, 1987). Indeed, scaling features in such systems often arise in conjunction with long-range spatiotemporal correlations following power-laws. Notably, physiological systems under neuro-autonomic regulation also exhibit dynamics characterized by long-range power-law correlations; a scale-invariant structure that undergoes a phase transition with transitions from sleep to wake (Kantelhardt et al., 2003; Schmitt et al., 2009), with circadian rhythms (Hu et al., 2004; Ivanov, 2007) and under clinical conditions (Ivanov et al., 1999; Goldberger et al., 2002). Further, the randomization procedure in the previous subsection (Fig. 10) clearly demonstrates that the scale invariant structure in quiet times characterized by a Gamma scaling function (Eq. 10) can arise only in the presence of a certain temporal order in θ-bursts occurrence. Thus, we next perform correlation analysis to quantify long-range features in the temporal organization of δ- and θ-burst durations.