Abstract

Phosgene, a widely used but highly toxic substance, may pose a serious risk to public safety and health because of the potential abuse and possible accidental leakage. Consequently, it is of great significance to develop a rapid, reliable, and sensitive detection method for this noxious agent. In this work, an aggregation-induced emission-based sensor, 3,6-bis(1,2,2-triphenylvinyl)benzene-1,2-diamine (DATPE), has been rationally designed for detecting phosgene by conjugation of o-phenylenediamine (OPD) core as the reactive recognition moiety decorated with two peripheral triphenylethylene (TPE) units. A light-up fluorescence response is achieved by the fast cyclization reaction of OPD part and phosgene along with the formation of 2-imidazolidinone ring, thus inhibiting the intramolecular charge transfer quenching process in the sensor. Moreover, an easy-to-use test paper with DATPE is fabricated for onsite visual detection of phosgene in the gas phase even at a concentration of as low as 0.1 ppm.

Introduction

Phosgene (COCl2) is a highly poisonous gas was utilized as a chemical warfare agent (CWA) and led to heavy casualties in World War I.1 This colorless gas is a lung irritant with a very deceptive poison, which does not induce irritation instantly after inhalation even at a lethal concentration. Severe pulmonary complications appear after a few hours, even causing death.2 This poisoning feature makes phosgene barely perceivable and raises the risk of death. Unlike other CWAs, such as sarin and soman, whose production and usage are very strictly regulated and prohibited by international laws, phosgene is much more easily available owing to its wide and important application in the production of pharmaceuticals, pesticides, and isocyanate-based polymers.3 In light of its unexpected leakage in industrial accidents and the potential abuse by terrorist, phosgene virtually poses a great threat to public health and safety. Consequently, it is of great significance to develop prompt, reliable, and portable methods for detecting phosgene.

Although several methods based on various principles have been reported for phosgene detection, such as gas chromatography, Raman, and electrochemical techniques,4−6 they are still limited by poor portability, high cost, and sophisticated procedures. In contrast, fluorescence-based sensing systems are strikingly advantageous because of their low cost, high sensitivity, simple operation, and great convenience for field detection.7 Over the past years, a variety of fluorescent sensors for phosgene have been developed by utilizing different fluorophores, such as BODIYs,8−12 coumarins,13,14 rhodamines,15,16 naphthalimides,17−20 and others.21−28 In general, the molecular design strategy mainly depends on phosgene-mediated reactions with electron-donating amine or hydroxyl groups in these sensors, resulting in the generation of electron-withdrawing carbamate, urea, or nitrile. These specific transformations typically lead to the suppression of fluorescence quenching processes, including photoinduced electron transfer (PET),9−11,13,21 intramolecular charge transfer (ICT),8,14,17−19,25 or excited state intramolecular proton transfer (ESIPT).20,22 Additionally, other sensing reactions mediated by phosgene involve the ring-opening of amino-containing spiro-(deoxy)lactam,15 cyclization of hydroxyl cinnamic acids,27 and hetero-cross-linking of amino-containing acceptor and donor fluorophores to give a FRET process.28

Despite the successful utilization of these above fluorescent sensors in detecting phosgene, most of them are based on aggregation-caused quenching (ACQ) fluorophores. They suffer from fluorescent reduction or even quenching in solid state, meaning that they are not good candidates for developing highly sensitive and portable sensing system for onsite detecting phosgene. On the other hand, aggregation-induced emission (AIE) fluorogenic molecules are weak or nonemissive in the solution state but are highly emissive in the solid state owing to the restriction of intramolecular rotation.29,30 Therefore, AIE-based sensing systems are more suitable for preparing solid-state portable test strip in comparison to ACQ counterparts. However, little attention has been devoted to this process. Up to now, there are only two AIE sensors based on tetraphenylethene23 and 2-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)benzothiazole24 with low detections limits of 1.87 and 0.34 ppm for detecting phosgene in gas phase, respectively. Nevertheless, the development of AIE-based probes for sensing gaseous phosgene with high sensitivity, fast response, and noticeable color changes still remains a challenge.

In this work, we report the rational design of an AIE-based sensor DATPE for light-up detecting phosgene, in which the reactive recognition moiety of o-phenylenediamine (OPD) core is conjugated with two peripheral triphenylethylene (TPE) units as AIE-active fluorophores (Scheme 1). The two free amino groups in DATPE are beneficial to the rapid and effective acylation by phosgene with a formation of five-membered imidazolidinone ring. As a result, the original ICT quenching process from the electron-donating OPD to peripheral TPE part in DATPE was greatly depressed, giving a highly AIE emissive sensing product 4,7-bis(1,2,2-triphenylvinyl)-1,3-dihydro-2H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-one (IMPTE). In particular, a portable test strip with DATPE was fabricated for gaseous phosgene detection with a visual detection limit as low as 0.1 ppm, representing one of the most sensitive sensors for phosgene in the gas phase (Scheme S1 and Table S1 in the Supporting Information).

Scheme 1. Chemical Structures of Sensor DAPTE with a Weak AIE Emission and the Sensing Reaction Product IMTPE with a High AIE Emission, Respectively.

Results and Discussion

The AIE-based sensor DATPE was readily prepared by two-step reactions of Suzuki coupling and subsequent reductive ring opening, as depicted in Scheme 2. Additionally, DATPE can rapidly react with phosgene that was in situ produced by the decomposition of triphosgene under the assistance of triethylamine (TEA),8 giving the proposed sensing product IMTPE. Then, their AIE properties were investigated by using a mixture of tetrahydrofuran (THF) and water system (Figure 1). As expected, both DATPE and IMTPE are almost nonemissive in a pure THF solution. Also, their photoluminescence (PL) intensity still remains very weak in aqueous mixtures with water fraction less than 70% (fw ≤ 70%), while the PL intensity begins to rise swiftly for fw > 70% due to the constraint of intramolecular motion thus turning on the AIE process. It is calculated that the PL intensities of DATPE and IMTPE are increased by 21- and 542-fold from those of the pure THF solution and THF–H2O mixture with 95% water content, respectively. The significant enhancement of AIE emission for IMTPE should be attributed to the inhibited ICT quenching process by the carbamylation of OPD moiety in DATPE. Therefore, it is revealed that the DATPE sensor can serve as a turn-on AIE probe for detecting phosgene.

Scheme 2. Synthetic Route for Sensor DATPE and Reaction Product IMTPE. Reagents and Conditions: (a) Pd(PPh3)4, Cs2CO3, CsF, Toluene/H2O, 90 °C for 2 d; (b) NaBH4, CoCl2, EtOH/THF, 90 °C for 3 h; and (c) Triphosgene, TEA, DCM, 10 min.

Figure 1.

PL spectra of DATPE (a) and IMTPE (b) in THF and THF–water mixtures (concentration = 10 μM; λex = 360 nm). Inset: plot of (I/I0–1) values versus the water fraction (fw) of THF-H2O mixture.

Considering their very weak emissions of the probe DATPE and proposed sensing product IMTPE in pure THF solution, the aqueous THF with 95% water content was used to monitor the PL response of DATPE toward phosgene in the solution phase. Specifically, the sensing reaction of DATPE with phosgene that was in situ generated by the decomposition of triphosgene was first performed in THF solution for 2 min. After that, the reaction mixture was quickly diluted to 95% aqueous solution for PL measurements. As shown in Figure 2a, a remarkable PL enhancement with a growing emission centered at 496 nm was clearly observed upon increasing the amount of triphosgene. Also, the PL intensity can be increased by 21-fold relative to that of the original DATPE solution after the addition of 2 equiv triphosgene, in which a bright blue fluorescence was easily detected by the naked eye under 365 nm light. The detection limit was evaluated to be 21 nM by fitting the emission titration data. Then, the selectivity of DATPE for detecting phosgene was investigated and compared with other reactive toxic chemicals, including acylating/phosphorylating agents (CH3COCl, BzCl, C2O2Cl2, SOCl2, SO2Cl2, POCl3, TsCl, BsCl), and a nerve-agent mimic diethyl chlorophosphate (DCP). As illustrated in Figure 2b, a dramatic PL enhancement occurred only for phosgene, while no remarkable change was detected for other analytes, confirming the high selectivity of DATPE toward phosgene over other analytes. Also, the different changes can be clearly and easily observed by the naked eye under a handheld 365 nm lamp (Figure 2b inset).

Figure 2.

(a) PL spectra of 10 μM DATPE in H2O-THF solution (fw = 95%) with different amounts of triphosgene (0–20 μM). Inset: plot of the relative PL intensity (I/I0) as a function of triphosgene concentration. (b) Relative PL intensity upon addition of addition of triphosgene/TEA (10 μM) and other analytes (20 μM): 0, blank; 1, phosgene; 2, oxalyl chloride; 3, diethyl chlorophosphate (DCP); 4, SOCl2; 5, SO2Cl2; 6, POCl3; 7, acetyl chloride; 8, tosyl chloride (TsCl); 9, benzenesulfonyl chloride (BsCl); and 10, benzoyl chloride (BzCl).

To further verify the proposed sensing mechanism (Scheme 1), the sensing reaction of DATPE with triphosgene/TEA was performed and analyzed by 1H NMR spectroscopy in CDCl3. As depicted in Figure 3a, the free sensor DATPE displays three types of proton signals, in which the broad peak with a chemical shift at 3.26 ppm was assigned to four hydrogen (H1) signals from free NH2 of OPD part. Upon the addition of triphosgene TEA, the H1 proton signal in DATPE disappeared but with a simultaneous appearance of a new peak at 6.67 ppm (Figure 3b). This new peak can be assigned to the NH protons (H1′) in the sensing reaction product IMTPE, indicative of the efficient intramolecular cyclization reaction with a rapid formation of five-membered 2-imidazolidinone ring. Besides, the H2 peak of aromatic hydrogens in OPD part was found to be downfield shifted with a Δδ of 0.17 ppm relative to free DATPE, which should be induced by the electron-withdrawing effect of carbonyl C=O group in the sensing reaction product. Also, the 1H NMR peaks of the reaction mixture can be matched pretty well with those of neat IMPTPE, further confirming the identity of the proposed sensing product.

Figure 3.

Partial 1H NMR (400 MHz) spectra of DATPE (a) upon addition of triphosgene with TEA continuously recorded after 1 min (b) and 10 min (c), as well as neat IMTPE (d) in CDCl3.

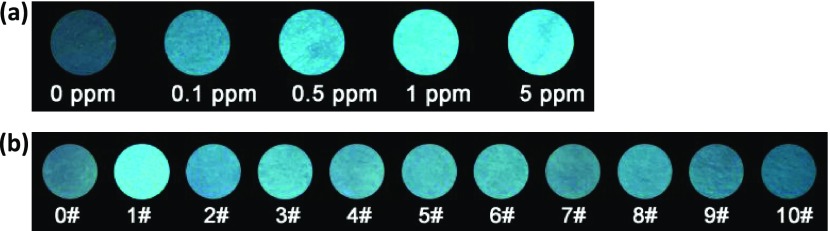

In contrast to ACQ-based fluorophores that suffer from fluorescence quenching in the aggregated state or at high concentrations, AIE-based fluorophores should be more advantageous for developing solid-state sensory devices to detect gaseous phosgene. Thus, a test strip has been facilely fabricated by immobilizing DATPE on a filter paper with polystyrene. Initially, the test strip embedded with DATPE is almost nonemissive under a handheld UV lamp because of the ICT quenching process (Figure 4). As expected, a light-up blue fluorescence is clearly observed after instant exposure of the strip to phosgene for several seconds and prolonged 1 min for a stable balance. The test strip becomes brighter with the increase of phosgene concentration (0.1–5 ppm). Remarkably, the test strip with DATPE can give a very noticeable response at a low concentration of 0.5 ppm phosgene gas. Also, it can still be detected by the naked eye even when the concentration of phosgene is as low as 0.1 ppm. This indicates that the AIE-based DATPE solid-state platform is among the most sensitive sensors for detecting phosgene gas, validating its ability for onsite monitoring of trace phosgene in specific events. Furthermore, the selectivity of the DATPE strip for phosgene over other analytes was evaluated. As shown in Figure 4b, after exposing different strips to various toxic vapors, the test paper only displays a turn-on fluorescence change for phosgene, whereas no significant change occurs in strips exposed to other analyte vapors. These above results indicate that this DATPE test strip is a potential tool for highly sensitive and selective detection of phosgene gas.

Figure 4.

Fluorescence images of DATPE loaded test strips upon exposure to different concentrations of phosgene gas (a) and various other analytes vapor ((b): 0, blank; 1, phosgene, 5 ppm; 2, oxalyl chloride; 3, POCl3; 4, BzCl; 5, BsCl; 6, TsCl; 7, DCP; 8, SOCl2; 9, SO2Cl2; 10, CH3COCl; others: 20 ppm) for 1 min.

Conclusions

In summary, we have rationally developed an AIE-based sensor DATPE for detecting phosgene with a light-up fluorescent response, which is readily constructed by conjugation of the central o-phenylenediamine moiety and two peripheral triphenylethylene units acting as the reactive recognition site and AIE-active fluorophores, respectively. The sensing reaction of DATPE to phosgene greatly depressed the original ICT quenching process, affording a highly AIE emissive product. More importantly, by utilizing such AIE property of the product, a practical test strip with DATPE has been fabricated for sensitively and selectively detecting trace amount of phosgene gas in air, which renders it highly promising for development of a portable onsite test kit for detecting phosgene gas. Moreover, these observations presented in this work would offer some new sights into the molecular design of AIE-based fluorescent sensors for phosgene.

Experimental Section

General Methods

All chemicals are commercially available and used as received without further purification. NMR spectra were taken on a Bruker AV400 at room temperature. Mass spectra (HRMS) were obtained in Waters GCT Premier. Fluorescence spectra and UV–vis spectra were recorded at room temperature on an Agilent Cary Eclipse spectrofluorophotometer and PerkinElmer Lambda 365, respectively.

Synthesis and Characterization

Compound 3

A mixture of Cs2CO3 (5.1 g, 15.6 mmol) and CsF (0.2 g, 1.3 mmol) was dissolved in water (2 mL) and added to a 250 mL round-bottom flask with a magnetic stir bar. Toluene (150 mL) was added into the reaction flask and the reaction mixture was bubbled by N2 for 2 h. Then, bromotriphenylethylene 1 (2.2 g, 6.6 mmol), 2,1,3-benzothiadiazole-4,7-bis(pinacolato)diboronic ester 2 (1 g, 2.6 mmol) and Pd(PPh3)4 (0.30 g, 0.26 mmol) were added into the mixture. The round-bottom flask was vacuumed and purged into N2 for 5 times. The reaction was heated at 90 °C for 48 h under nitrogen atmosphere. After that, the reaction mixture was cooled down to room temperature and extracted by CH2Cl2 (100 mL x 2). The combined organic layer was washed with water (200 mL x 5), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and then evaporated under reduced pressure. The crude product was further purified using column chromatograph (petroleum ether/CH2Cl2, 1/2) to give a yellow solid (0.40 g, 0.6 mmol, yield: 24%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, d6-acetone) δ 7.23 (s, 2H), 7.18–6.90 (m, 30H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, d6-acetone) δ 155.3, 144.5, 144.4, 143.7, 143.1, 137.8, 136.9, 131.9, 131.8, 131.3, 130.7, 128.6, 128.4, 128.3, 127.7, 127.6, 127.4. Electron ionization-mass spectrometer (EI-MS): m/z calcd for C46H32N2S: 644.2286, found: 644.2290 [M]+.

DATPE

Compound 3 (0.40 g, 0.62 mmol) was dissolved in a mixed solvent of ethanol and THF (1:1) in a 100 mL round-bottom flask with a magnetic stir bar. Sodium borohydride (0.07 g, 1.85 mmol) was added to the reaction flask and then cobalt chloride hexahydrate (0.015 g, 0.06 mmol) was added with rapid stirring. The reaction mixture was heated at 90 °C for 3 h. After that, the reaction mixture was cooled down to room temperature and extracted by CH2Cl2 (50 mL x 2). The combined organic layer was washed with water (100 mL x 5), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and then evaporated under reduced pressure. The crude product was further purified using column chromatograph (CH2Cl2/CH3COOC2H5, 50/1) to give the sensor DATPE as a light green solid (0.20 g, 0.32 mmol, yield: 52%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.21–6.88 (m, 30H), 6.34 (d, J = 18.7 Hz, 2H), 3.26 (s, 4H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 143.6, 143.1, 142.5, 141.9, 138.0, 133.3, 133.1, 131.5, 130.6, 130.4, 130.0, 129.6, 127.8, 127.4, 126.9, 126.8, 123.0. EI-MS: m/z calcd for C46H36N2: 616.2878, found: 616.2874 [M]+.

IMTPE

Compound DATPE (50 mg, 0.08 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous DCM (150 mL), which was cooled to 0 °C in an ice bath. Then, triphosgene (48 mg, 0.16 mmol) and TEA (16.4 mg, 0.16 mmol) were added into the mixture with rapid stirring. After that, the reaction was recovered to room temperature and stirred for 10 min. The solvent of the mixture was removed under reduced pressure, and the crude product was purified by silica gel flash column chromatography (CH2Cl2/CH3COOC2H5, 20/1) to afford the pure product as a white solid (38 mg, 0.06 mmol, yield: 75%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.19–6.96 (m, 30H), 6.65 (s, 2H), 6.51 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 154.4, 143.1, 142.8, 142.0, 135.8, 131.5, 130.8, 130.6, 128.2, 128.0, 127.9, 127.4, 127.3, 127.2, 127.0, 124.7, 124.4. EI-MS: m/z calcd for C47H36N2O: 642.2671, found: 642.2676 [M]+.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported from National Natural Science Foundation of China (21702213), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20181001), and TAPP and PAPD of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.9b03286.

Chemical structures of recently reported fluorescent probes for phosgene detection; details of assay experiments; and copies of NMR and MS spectra of all synthesized compounds (PDF).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Szinicz L. History of chemical and biological warfare agents. Toxicology 2005, 214, 167–181. 10.1016/j.tox.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivera D. S.; Hoard-Fruchey H.; Sciuto A. M. Evaluation of an in vitro screening model to assess phosgene inhalation injury. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2017, 27, 45–51. 10.1080/15376516.2016.1243183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babad H.; Zeiler A. G. Chemistry of phosgene. Chem. Rev. 1973, 73, 75–91. 10.1021/cr60281a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davydova M.; Stuchlik M.; Rezek B.; Larsson K.; Kromka A. Sensing of phosgene by a porous-like nanocrystalline diamond layer with buried metallic electrodes. Sens. Actuators, B 2013, 188, 675–680. 10.1016/j.snb.2013.07.079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Juillet Y.; Dubois C.; Bintein F.; Dissard J.; Bossee A. Development and validation of a sensitive thermal desorption-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (td-gc-ms) method for the determination of phosgene in air samples. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2014, 406, 5137–5145. 10.1007/s00216-014-7809-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal R. L.; Farrar L. W.; Di Cecca S.; Jeys T. H. Raman spectra and cross sections of ammonia, chlorine, hydrogen sulfide, phosgene, and sulfur dioxide toxic gases in the fingerprint region 400–1400 cm(-1). AIP Adv. 2016, 6, 025310 10.1063/1.4942109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.; Wu D.; Yoon J. Recent advances in the development of chromophore-based chemosensors for nerve agents and phosgene. ACS Sens. 2018, 3, 27–43. 10.1021/acssensors.7b00816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Peng A.; Jie X.; Lv Y.; Wang X.; Tian Z. A bodipy-based fluorescent probe for detection of subnanomolar phosgene with rapid response and high selectivity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 13920–13927. 10.1021/acsami.7b02013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T.-I.; Kim D.; Bouffard J.; Kim Y. Rapid, specific, and ultrasensitive fluorogenic sensing of phosgene through an enhanced pet mechanism. Sens. Actuators, B 2019, 283, 458–462. 10.1016/j.snb.2018.12.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xia H.-C.; Xu X.-H.; Song Q.-H. Bodipy-based fluorescent sensor for the recognization of phosgene in solutions and in gas phase. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 4192–4197. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b00203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayar M.; Karakuş E.; Güner T.; Yildiz B.; Yildiz U. H.; Emrullahoğlu M. A bodipy-based fluorescent probe to visually detect phosgene: Toward the development of a handheld phosgene detector. Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 3136–3140. 10.1002/chem.201705613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T.-I.; Hwang B.; Bouffard J.; Kim Y. Instantaneous colorimetric and fluorogenic detection of phosgene with a meso-oxime-bodipy. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 12837–12842. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b03316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia H.-C.; Xu X.-H.; Song Q.-H. Fluorescent chemosensor for selective detection of phosgene in solutions and in gas phase. ACS Sens. 2017, 2, 178–182. 10.1021/acssensors.6b00723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng W.; Gong S.; Zhou E.; Yin X.; Feng G. Readily prepared iminocoumarin for rapid, colorimetric and ratiometric fluorescent detection of phosgene. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1029, 97–103. 10.1016/j.aca.2018.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y.; Zhou X.; Jung H.; Nam S.-J.; Kim M. H.; Yoon J. Colorimetric and fluorescent detecting phosgene by a second-generation chemosensor. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 3382–3386. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b05011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y.; Chen L.; Jung H.; Zeng Y.; Lee S.; Swamy K. M. K.; Zhou X.; Kim M. H.; Yoon J. Effective strategy for colorimetric and fluorescence sensing of phosgene based on small organic dyes and nanofiber platforms. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 22246–22252. 10.1021/acsami.6b07138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.-L.; Zhong L.; Song Q.-H. A ratiometric fluorescent chemosensor for selective and visual detection of phosgene in solutions and in the gas phase. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 1530–1533. 10.1039/C6CC09361B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.-L.; Zhang C.-L.; Song Q.-H. Selectively instant-response nanofibers with a fluorescent chemosensor toward phosgene in gas phase. J. Mater. Chem. C 2019, 7, 1510–1517. 10.1039/C8TC05281F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.-L.; Zhong L.; Song Q.-H. Sensitive and selective detection of phosgene, diphosgene, and triphosgene by a 3,4-diaminonaphthalimide in solutions and the gas phase. Chem. - Eur. J. 2018, 24, 5652–5658. 10.1002/chem.201800051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiti K.; Ghosh D.; Maiti R.; Vyas V.; Datta P.; Mandal D.; Maiti D. K. Ratiometric chemodosimeter: An organic-nanofiber platform for sensing lethal phosgene gas. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 1756–1767. 10.1039/C8TA10481F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X.; Zeng Y.; Chen L.; Wu X.; Yoon J. A fluorescent sensor for dual-channel discrimination between phosgene and a nerve-gas mimic. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 4729–4733. 10.1002/anie.201601346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.; Wu D.; Kim J.-M.; Yoon J. An esipt-based fluorescence probe for colorimetric, ratiometric, and selective detection of phosgene in solutions and the gas phase. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 12596–12601. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b03988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H.; Wu Y.; Zeng F.; Chen J.; Wu S. An aie-based fluorescent test strip for the portable detection of gaseous phosgene. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 9813–9816. 10.1039/C7CC05313D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L.; Feng W.; Feng G. An ultrasensitive fluorescent probe for phosgene detection in solution and in air. Dyes Pigm. 2019, 163, 483–488. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2018.12.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.-Q.; Cheng K.; Yang X.; Li Q.-Y.; Zhang H.; Ma Z.; Lu H.; Wu H.; Wang X.-J. A benzothiadiazole-based fluorescent sensor for selective detection of oxalyl chloride and phosgene. Org. Chem. Front. 2017, 4, 1719–1725. 10.1039/C7QO00378A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P.; Liu N.; Liu C.; Jia Y.; Huang L.; Zhou G.; Li C.; Wang S. A colorimetric and ratiometric fluorescent probe with ultralow detection limit and high selectivity for phosgene sensing. Dyes Pigm. 2019, 163, 489–495. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2018.12.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu P.; Hwang K. C. Rational design of fluorescent phosgene sensors. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 4594–4597. 10.1021/ac300737g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.; Rudkevich D. M. A fret approach to phosgene detection. Chem. Commun. 2007, 20, 1238–1239. 10.1039/b614725a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei J.; Leung N. L. C.; Kwok R. T. K.; Lam J. W. Y.; Tang B. Z. Aggregation-induced emission: Together we shine, united we soar!. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 11718–11940. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei J.; Hong Y.; Lam J. W. Y.; Qin A.; Tang Y.; Tang B. Z. Aggregation-induced emission: The whole is more brilliant than the parts. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 5429–5479. 10.1002/adma.201401356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.