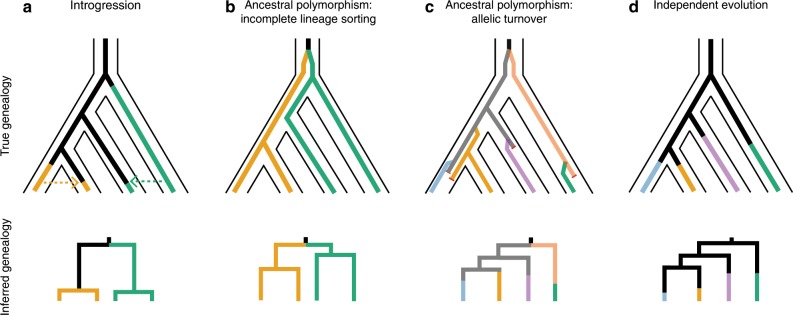

Fig. 1. True (top row) and inferred (bottom row) genealogies under four mimicry evolution hypotheses.

Colors represent distinct mimicry alleles/phenotypes. a Mimicry alleles are shared because of introgressive hybridization. b Mimicry evolves ancestrally, and descendant lineages inherit and maintain the ancestral alleles. c Mimicry evolves ancestrally, and alleles are gained and lost so that the extant alleles are distinct from the ancestral alleles. d Unique mimicry alleles arise by the independent evolution of mimicry. Under introgression and incomplete lineage sorting (ILS), the inferred genealogies will show alleles grouping by phenotype rather than species (a, b), but the branch lengths will be relatively shorter for introgression than for ILS. Under allelic turnover and independent evolution, the inferred genealogies will result in alleles grouping by species (c, d), but the branch lengths are expected to be longer for allelic turnover because of underlying balancing selection. A history of allelic turnover will also leave behind population genetic signatures of balancing selection, such as elevated Tajima’s D in the region of interest. Under allelic turnover, the amount of shared ancestral variation should track phylogenetic relatedness, because recombination and gene conversion will erase the evidence of ancestral variants as a lineage ages. Because shared ancestral variation is more likely to be retained at younger timescales, allelic genealogies may show alleles of one species nested within another species for younger lineages. In contrast, independent evolution need not involve balancing selection, and if variants are shared among lineages, these should not be correlated with the lineages’ phylogenetic proximity.