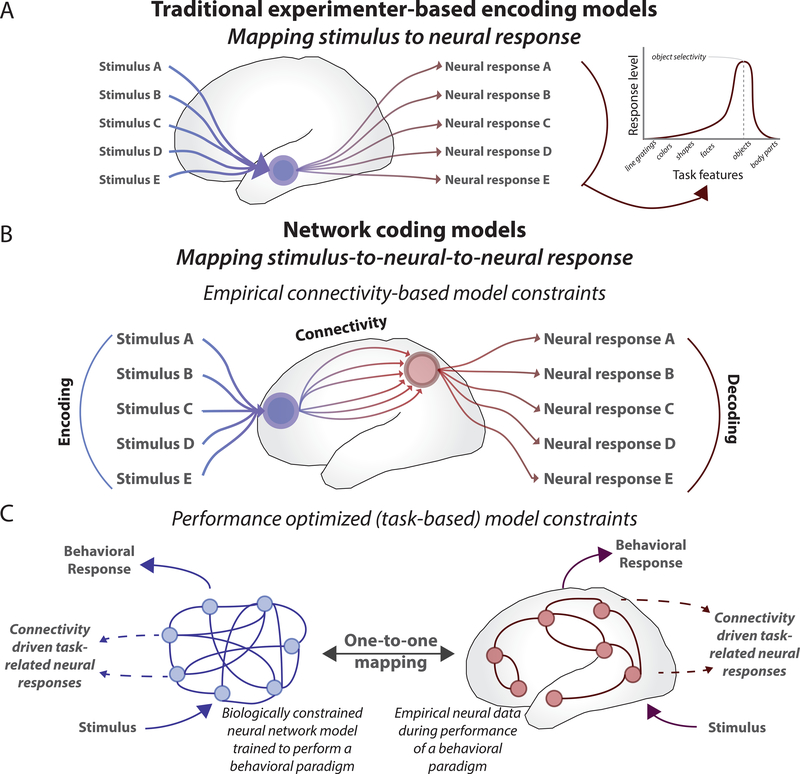

Figure 3. From experimenter-based encoding/decoding models to network coding models.

A) Traditional encoding models impose experimenter-based stimulus constraints to measure neural responses. These measures represent the degree to which a neural entity responds to different task features. Despite the simplicity of these models, the neural responses predicted by these encoding models may not reflect how the brain actually responds to the task information. Instead, these models focus on whether the experimenter can map task information onto neural responses, rather than how a neural entity actually encodes task information through its network connectivity [89]. B) Network coding models (see Figures 1 and 2) utilize mechanistic constraints (e.g., brain network connectivity) to investigate how a neural entity’s connections might drive its task-related response. The first approach is to estimate connectivity directly, and then predict (via activity flow estimation) neural responses in a downstream neural entity to characterize how those responses likely emerge from activity flow processes via connectivity. C) The second, more top-down approach (see Figure 4) uses behavior or task performance to learn the network connectivity patterns necessary to encode task representations (through learning algorithms). These artificial neural networks implicitly model activity flow processes to implement the neural computations underlying cognitive task functions. When provided with sufficient biological constraints (e.g., the visual system’s “deep” network architecture), these models can be directly compared to empirical data, producing unique insight into the network principles that are instrumental to performing cognitive processes (which include cognitive encoding and decoding) [41,46,48].