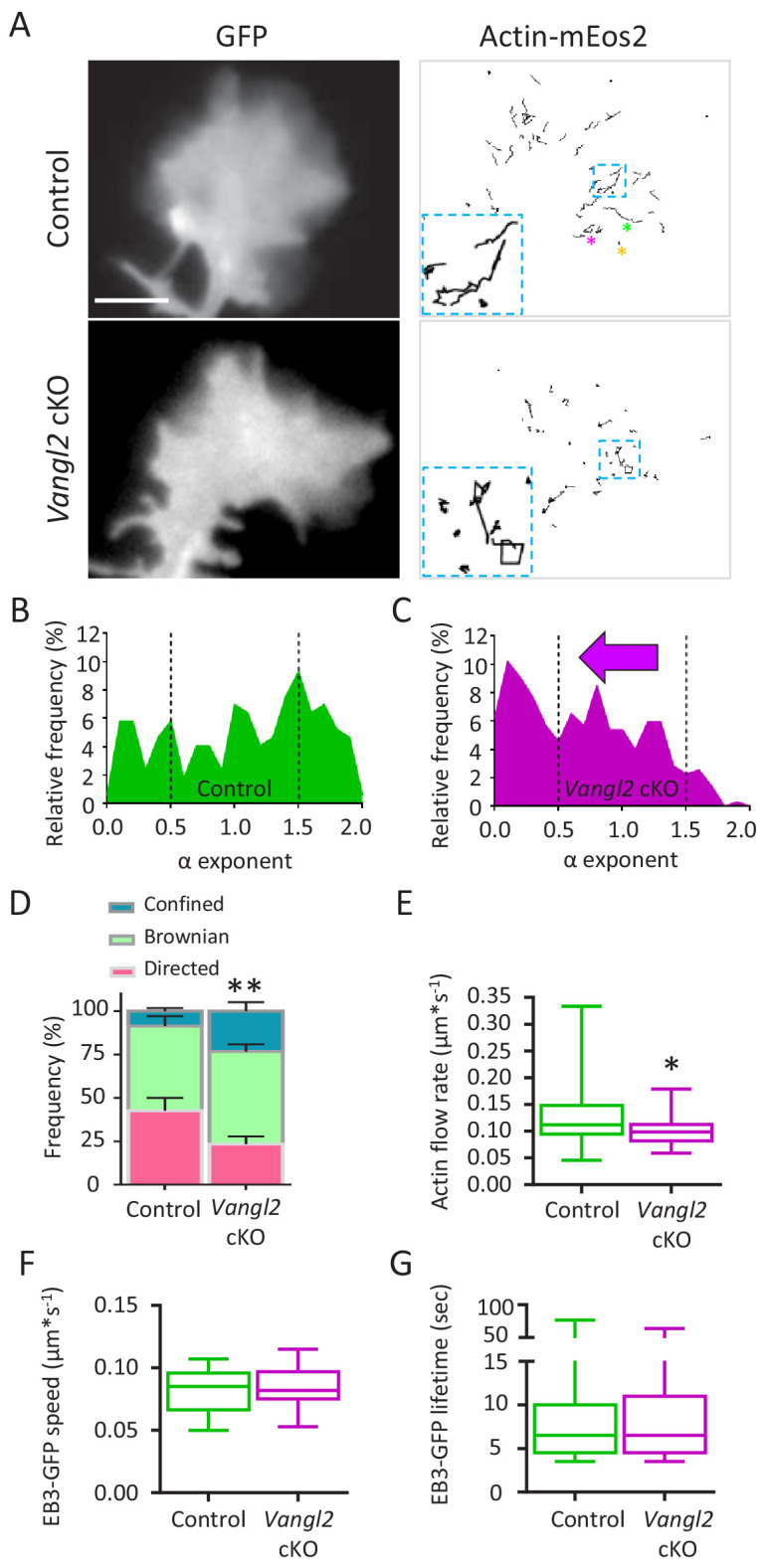

Figure 4. Deletion of Vangl2 decreases actin treadmilling.

(A) Representative images of growth cones from control and Vangl2 cKO neurons expressing GFP and actin-mEos2. Images show the growth cone filled with GFP (left) and the trajectories of single actin-mEos2 molecules (in black) recorded over a 3 min period at 2 Hz (right). Insets show higher-magnification examples of the variability in individual trajectories. Scale bar, 5 µm. (B, C) Distribution of actin-mEos2 molecules α values in control and Vangl2 cKO neurons. n = 184–440 trajectories, 6–7 neurons. (D) Frequency distribution of directed, Brownian and confined trajectories of actin-mEos2 molecules in control and Vangl2 cKO neurons plated on Ncad-Fc substrates. (E) Speed of retrograde actin flow as extracted from the directed trajectories in controls and Vangl2 cKO neurons. n = 73–79 trajectories, 6–7 neurons. n = 8 sister cultures (DIV3) from eight different mice. (F, G) Quantification of the speed and lifetime of EB3-GFP particles in control and Vangl2 cKO neurons. n = 18–19 neurons. Data are presented as box-and-whisker plots (min/max) based on three independent experiments; *p<0.05, **p<0.01 by the Mann-Whitney test (D, E).