Abstract

The study investigated perception of workload balance and employee job satisfaction in work organisations. It sought to find out the extent to which employee perception of workload balance influences job satisfaction. Seven hundred and sixty-four (764) randomly selected employees from 8 multinational organizations and two private universities in Nigeria participated in the study. Structural equation modelling was employed. Results show that comparison of workload with those of colleagues and employees' role alliance with their competencies significantly influence their perception of workload balance and job satisfaction, organisation's staff strength influences perception of workload balance and employees' perception of workload balance significantly influences job satisfaction.

Keywords: Workload, Employee workload, Perception of workload balance, Job satisfaction, Role alliance, Economics, Business, Psychology, Sociology, Activism, Aging and life course

Workload, Employee workload, Perception of workload balance, Job satisfaction, Role alliance, Economics; Business; Psychology; Sociology; Activism; Aging and life course.

1. Introduction

Employee workload and task complexities are functions of organisational structures. Even within the same organisation, employee task requirements vary since employees of the same rank may be unequally tasked. The discrepancies in workload may be largely influenced by educational qualification, area of specialisation or position in the organisation. In most organisations, the variability in employee workload may be largely influenced by the departments to which they belong. But even within the same department, there is no guarantee that employee workload will balance. An Employee's perception of workload balance or imbalance as a result of perceived discrepancies between his workload and that of other organisational members can cause disaffection (Sravani, 2018). According to equity theory, an employee will feel unfairly treated if he perceives that colleagues that put in the same efforts at work as him earn more than him or if he earns the same as those who put less effort than him.

Organisational systems are made up of many interdependent and interrelated subsystems that work together to complement one another to facilitate the attainment of organisational goals in all categories, whether large or small. Employees in each organisation have various degrees of workload that they contend with on a daily basis. If for any reason the workload changes, such change alters the stress level of employees as well as their perception of fairness in workload balance, especially when the change is positive. But whether positive, as in the case of an increase in workload; or negative, as is the case in a reduction in workload; it has implications on employee job satisfaction and ultimately, job performance (Ali and Farooqi, 2014). While a positive change in workload may precipitate ill feeling among the concerned employees, a negative change may reduce the employee's capacity to exploit his ability, thus leading to the likelihood of inefficiency on the part of such an employee. Despite the availability of some extant studies on the impact of workload balance on organisational outcomes, no existing study has either investigated employee perception of workload balance or examined employee perception of workload balance as a result of a comparison of their workload with those of colleagues in the organisation. Given the possible consequences of perceived workload imbalance arising from employees' comparison of workload with those of colleagues and the possible feeling of inequity and demotivation that may be associated with perceived workload imbalance, the need to assign jobs in a manner that will reduce employee perception of workload imbalance in an organisation becomes very important to policy makers in order to avoid ill consequences that may be associated with such perception of workload imbalance. This underscores the essence of this study.

1.1. Objective of the study

The main objective of the study was to investigate the relationship between employees' perception of work load balance and job satisfaction. The specific objectives were to: Determine the extent to which comparison of workload with those of colleagues, the uniqueness of employee's area of specialisation, organisation's staff strength and employees' role alliance with their competencies influence their perception of workload balance.

2. Literature review

2.1. Concept of employee workload

Employee workload is a critical determinant of their productivity and turnover (Rajan, 2018) because if their workload is below the standard workload, it will evoke laziness and provide opportunity for them to be idle and indulge in non-productive activities like group politics, with its attendant implications on performance. On the other hand, if the workload is above the standard workload, there is a tendency that the employee will be overwhelmed; this will result in hazards like burnout and subsequent breakdowns as well as ill feelings and dissatisfaction and subsequently cause them to quit the job for less strenuous jobs where available. Two performance indicators in contemporary organisations are employee productivity and turnover. The importance of these indicators cut across all kinds of sectors in this current business world because they are directly associated with growth of employees and organizations as well.

Among other things, employee workload refers to the intensity of job assignments (Nwinyokpugi, 2018). It is the amount of work assigned to or expected from a worker in a specified time period. Employee workload has also been defined as the perceived relationship between the amount of mental processing capability or resources required to complete a task (Hart and Staveland, 1998). Empirical studies indicate that employee workload impact on emotional commitment (Erat et-al, 2017) exhaustion (Ali S and Farooqi, 2014; Portoghese et al., 2014); individual and organisational stress (Erat et al., 2017; Rahim et al., 2016; ; Hombergh et al., 2009; as well as Xiaoming et al., 2014) employee performance and job satisfaction (Herminingsih and Kurniasih, 2018; Liu and Lo, 2018; Akobo, 2016; Rahim et al., 2016; Ali S and Farooqi, 2014; as well as Hombergh et al., 2009), and turnover intention (Qureshi et al., 2013).

2.1.1. Workload management

Given the tendency of workloads to vary among employees in different departments of an organisation and even within the same department, the need to manage workloads in an organisation becomes very important. Workload management is the adjustment of employee workloads to minimise the discrepancy between actual and potential workload (Van den Bossche et al., 2010). Among other things, workload management helps to reduce the need for specialized and technical skills as well as facilitate the organization, management and monitoring of workloads in line with business goals. Workload management also “allows business critical applications to receive the priority they deserve while other applications run as resources are available; provides the necessary resources to plan for changes in business workloads; and makes system more adaptive and responsive to changing environments” (Dasgupta, 2013). But workload management must seek to minimise the discrepancy between assigned workloads and the capacity of the assignee so that the assignee will not be overwhelmed by the workload. To this end, the main objective of workload management is to minimise workload imbalance in organisations.

2.2. Theoretical review

Some theories that explain employee job satisfaction are presented below. Many researchers and theorists have made attempts to explain why people feel the way they do in regards to their job and thus suggest reasons for employees’ work attitude. Foremost among these theorists is Locke (1969), who is unarguably the most famous contributor to job satisfaction models. Other theories beside that of Locke are the Dispositional Theory and the social influence hypothesis, among others.

2.2.1. Comparison process theory

Proposed by Vroom (1964) and also known as a “Subtractive Theory” of job satisfaction, comparison process theory states that the degree of affection experienced in a job results from some perceived comparison between the individual's standard and what he receives from the job. Smith, Kendal and Hulin (1969) and Locke (1969), in their contribution to Vroom's (1964) comparison process theory concluded that the individual's value and frame of reference serve as standard of comparison more than needs.

2.2.2. Social influence hypothesis

Postulated by Salancik and Pfeffer (1977), the Social Influence theory questioned the validity of the comparison process theory. The challenge was informed by the belief that workers decide how satisfied they are by observing others on similar jobs and making inference about their satisfaction on the basis of such observation. Their position was corroborated by Weiss and Shaw (1979) as well as White and Mitchell (1979). The theory recognizes the social nature of man in the workplace as it does influence satisfaction. It also exhibits reasonable consistency with Adam Smith's Equity Theory which states that a worker consciously or unconsciously compares his input/output ratio with that of other persons on the same job level. That if equity exists between focal person A and reference person B, then there will be satisfaction but if there is perceived discrepancy, negative reactions could occur. In order to situate job satisfaction in an environmental context, a theory known as the social influence hypothesis was developed by a social psychologist, Bandura, to describe a social effect where individuals want what they perceive others around them want.

2.2.3. Theoretical framework

The two theories of job satisfaction, comparison process theory and social influence hypothesis, underpin this study and thus form the framework of the study.

2.3. Empirical review

Some of the studies that have examined employee workload are presented in this section.

2.3.1. Employee perception of workload in some organisations

Mayasari and Gustomo (2014) investigated workload analysis in CV.SASWCO PERDANA. They sought to find out how the workload can be evenly distributed in CV. Saswco Perdana, to enable employees have clear job analysis. Primary data was collected by questionnaires and workload type from 12 employees and management. They found that several job positions were overloaded and some under-loaded. The need for companies to review the job description for employees by balancing their workload was suggested.

Chen et al. (2013) investigated workload and performance levels of work situation analysis of employees with application to a Taiwanese hotel chain. They sought to find out ways to conduct manpower planning in organisation using workload analysis. They employed direct sampling because there are numerous number of employees engaged in irregular task. They found that three employees have a very high workload, seven are thinking about high work load and two have the normal workload. The need for the organisation to recruit additional employees to equalise employee workload was suggested, among others.

Ford and Jin (2015) tested hypothesis in two studies on the association between workload and depressive symptoms when it exceeds occupational norms for time pressure to ascertain how incompatibility between workload and occupational norms for time pressure predicts depressive symptoms. They found that there was significant association between workload levels exceeding occupational norms for time pressure and depressive symptoms. The results were consistent with those obtained in a second cross-sectional study with some of the effect accounted for by psychological contract violation, thus indicating the tendency for strong association between workload and depressive symptoms when it exceeds occupational norms for time pressure.

2.3.2. Workload and employee burnout

Herminingsih and Kurniasih (2018) examined “the influence of workload perceptions and human resource management practices on employees' burnout with a view to assessing the extent to which the lack of service is a result of employee burnout. The study focused on non-faculty employees at UMB and the data were elicited from the respondents using a questionnaire with self-rating scale. Subsequently, the data were analysed using structural equation modelling. Results indicated that employee workload is high and is significantly related to burnout. Furthermore, human resource management practices were also found to significantly and negatively affect the employees’ burnout.

Rajan (2018) investigated negative impacts of heavy workloads through a comparative study among sanitary workers of multi-specialty (MS) and single specialty (SSP hospitals). The purpose of the study was to understand sanitary workers’ perception of various risk factors as a result of heavy workload and the impacts of such heavy workload on their health, work and behaviour in private MS and SS hospitals in Tirunelveli city, Tamilnadu, India. Convenience sampling technique was used to select a sample of 120 sanitary workers from MS and SS hospitals. The findings of the study reveal that there is no difference between the perception of sanitary workers in both categories of organisations on risk factors that influence workload as well as how it impacts on their health, work and behaviour.

2.3.3. Employee workload and job satisfaction

Liu and Lo (2018) investigated workload, autonomy, burnout, job satisfaction, and turnover intention among Taiwanese reporters using an integrated model, with a view to examining the relationship between the five variables among Taiwanese reporters. A survey design was employed using a sample of 1,099 reporters. Results indicated a significant association between workload and news autonomy and burnout. Furthermore, a significant negative relationship was found between burnout and job satisfaction, which in turn had a significant effect on turnover intention. The implication of the findings is that workload and news autonomy are significant predictors of burnout and that job satisfaction mediates between burnout and turnover intention.

Lea et al. (2012) investigated the impact of workload on job satisfaction and stress among community pharmacists' through an extensive review of the literature. They reviewed and evaluated literature on the research problem with particular emphasis on pharmacists' workload and its impact on stress levels and job satisfaction. The study area was the UK. They employed electronic databases from 1995 to 2011 and made manual searches for documents not available electronically. They analysed the findings and research methodology of workload's impact on the job satisfaction and stress level of pharmacist. They found that workload levels were increasing and there was a relationship between increased workload and decreasing job satisfaction.

De Cuyper and De Witte (2006) investigated Autonomy and workload among temporary workers with a view to ascertaining their effects on job satisfaction and some other organizational outcomes. A survey design was employed and the sample was made up of 560 respondents consisting of 189 temporary employees and 371 permanent employees. The data were analysed using multiple regression technique. Results indicated that job satisfaction predicted organizational commitment and workload was found not to be a significant predictor of job satisfaction by temporary workers, whereas it was found to be predictive by permanent employees. They also found that the effects of contract type are not mediated by autonomy or by workload.

Based on the above empirical findings, the following null hypothesis was formulated:

H01

There is no significant relationship between employee perception of workload balance and job satisfaction

2.3.4. Workload perception and employees’ areas of specialisation

Organisations create positions for employees and design jobs for them. Thus, work positions are specific to organisations (Ford and Jin, 2015). The positions created by organisations are occupied by individual employees on the basis of their roles which depend on their occupation and specialisation. Thus, roles are specific to individuals because their occupations provide a transcendent organizing framework for the creation of positions and work roles across organizations. Employees that share the same occupation in different organizations usually also have similar job attributes. To this end, some of the disparities experienced by most individual employees are informed by the discrepancies that exist in conditions across occupations. Thus, it is theoretically rational that work characteristics at the occupational level of analysis have been shown to predict work-related outcomes (Ford, 2012; Ford and Jin, 2015), notwithstanding the fact that the characteristics of job roles vary considerably within these occupations. Based on the foregoing, the following null hypothesis is formulated:

H02

There is no significant relationship between uniqueness of respondent's area of specialization and perception of workload balance.

2.3.5. Workload perception and employees' comparison of workload with colleagues’

Flowing from the theoretical framework of this study, which consists of comparison process theory and social influence hypothesis, it is evident that employees compare their inputs with those of colleagues with similar occupational attributes. In the same vein, employees compare their workloads with those of colleagues with similar and/or dissimilar attributes. To this end, the following hypotheses are formulated:

H03

There is no significant relationship between comparison of workload with those of colleagues and employees' perception of workload balance

H04

There is no significant relationship between comparison of workload with those of colleagues and job satisfaction

2.3.6. Workload perception and Employee's interest in the job

Employee's capabilities and interest in a job role have also been found to be a significant factor in his perception of workload and stress (Nwinyokpugi, 2018). Employees who possess the capabilities to perform a job enjoy positive workload provided the pressure is not excessive. “Occupational workload is discomfort at a personal level when it exceeds a person's coping capabilities and resources to handle them adequately” (Malta, 2004). Employees who are not interested in their job roles or not satisfied with the job field often regard extra work as fatigue and such extra work often contribute to job stress. Loss of interest in a job may be caused by role mismatch, inadequate remuneration and work conditions, among others. To this end, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H05

There is no significant relationship between job roles alignment and job satisfaction

2.3.7. Employee perception of workload and organisation staff strength

When an organisation is understaffed or lacks adequately trained staff due to expansion or unfavourable staff turnover, there is the likelihood that the existing staff will be overstretched. When an organisation lacks adequate number of staff or adequately trained staff to man the existing job roles, more of the industry workload will fall on the individual employee's shoulders (Nwinyokpugi, 2018). This will stimulate employees' perception of workload imbalance owing to the increase in workload vis-à-vis what hitherto obtained in the organisations. Whether the employees adjust to the situation on the short-run or not, only an increase in staff strength will correct this perception. Even when workload management strategies are put in place such as prioritisation, delegation, and automation, among others, the feeling that the staff strength is deficient may still cause some employees to perceive workload imbalance in the organisation.

H06

There is no significant relationship between organisation's staff strength and employee perception of workload balance.

2.3.8. Gap in literature

Till date, extant literature on employee workload and job satisfaction in organisations is very scanty. While Lea et al. (2012) investigated workload and job satisfaction and stress among community pharmacists, Herminingsih and Kurniasih (2018) examined “the influence of workload perceptions and human resource management practices on employees' burnout” and Rajan (2018) investigated negative impacts of heavy workloads among sanitary workers. On the other hand, Liu and Lo (2018) investigated workload, autonomy, burnout, job satisfaction, and turnover intention among Taiwanese reporters. The studies of Mayasari and Gustomo (2014) and Chen et al. (2013) focused on employee workload in specific organisations with a view to ascertaining how workload can be evenly distributed. De Cuyper and De Witte (2006) investigated the impact of autonomy and workload on job satisfaction among temporary and permanent workers. The findings of the studies are also varied, thus indicating the need for further studies. Lea, Corlett and Rodgers (2012), Herminingsih and Kurniasih (2018) and Liu and Lo (2018) found significant relationship between workload and job satisfaction, the findings of De Cuyper and De Witte (2006) did not totally support this view as the temporary workers’ perception was contrary to this view. Mayasari and Gustomo (2014) and Chen et al. (2013) found that the employees in the organisations investigated had high workloads and thus suggested the need to redesign jobs or employ additional workers. But they did not relate employee workload to job satisfaction. Besides, no existing study has either investigated employee perception of workload balance or examined employee perception of workload balance as a result of a comparison of their workload with those of colleagues in the organisation. This study sought to fill these gaps.

3. Research design

3.1. Population of the study and sampling procedure

The population of the study consisted of employees of 8 multinational companies in Nigeria (Julius Berger, MTN, Coca cola, Mobil, Nestle, Cadbury, 7UP and Guinness) and two private universities (Benson Idahosa and Landmark Universities, both in Nigeria). Thus, the study employed two samples. The participants in the first sample were randomly selected from alumni members of the University of Benin, Nigeria who are employees of the targeted multinational companies and who had completed their MBA within the past 15 years while the second sample consisted of employees from the two private universities The choice of these organisations was informed by their perceived high utilization rate of employees as against most public organisations where employee utilization is perceived to be low, owing to perceived conspicuous overstaffing (Igbokwe-Ibeto et al., 2015; Briggs, 2007 and Ukaegbu, 1995).

The inclusion of multinational companies was informed by the perceived international outlook of the organizations. The respondents in the first sample were requested to participate in the study via the social media (WhatsApp and Facebook) and they received the questionnaires via WhatsApp and Facebook. The selection of participants is consistent with the participant selection method used by Inegbedion et al. (2016) as well as Inegbedion and Obadiaru (2018) and Inegbedion (2018). Respondents in the second sample were contacted physically and questionnaires were administered to them physically. Seven hundred and sixty four employees from the 8 multinational organizations and the 2 private universities (436 males and 328 females), out of nine hundred and sixty (960) that were requested, voluntarily participated in the study. Stratified random sampling was employed.

3.2. Measurement

The study adapted measurement items related to extant literature and employed a 5-point Likert scale for all the measures (see Appendix). The questionnaire was designed by the authors and the constructs employed were informed mainly by the variables found to have featured in extant studies (Herminingsih and Kurniasih, 2018; Liu and Lo, 2018; De Cuyper and De Witte, 2006; Mayasari and Gustomo, 2014; as well as Chen et al., 2013). The questionnaire contained fifteen 5-points Likert scale questions dealing with factors related to employees' perception of workload such as comparison of workload with those of colleagues, area of specialization, organization's staff strength and role alignment as well as employee job satisfaction. Employees' perception of workload was measured as low, normal and high workloads based on a comparison of workload with what he expects to get and a comparison of workload with those of colleagues of same, lower or higher income levels. The measurement procedure was informed by comparison process theory and social influence hypothesis. Employee workload perception and organisational staff strength were operationalized by 2 items each. Comparison of workload with employees and uniqueness of employees area of specialisation were operationalized by 4 items each while role mismatch was operationalized by 3 items.

3.2.1. Reliability

The instrument featured items of the Likert-type scale. Cronbach alpha was used to test for reliability of the instrument. The coefficients of reliability were found to be 0.81, 0.68, 0.67, 0.68, 0.69 and 0.41 for the comprehensive questionnaire, employee perception of workload, comparison of workload with colleagues, employees' area of specialisation, organisation's staff strength and role alignment respectively (see Table 1). The alpha coefficient obtained for the construct row alignment was 0.41. This value is consistent with the low reliability measure for this construct since the score is less than 0.70. A principal components analysis was conducted, which resulted in significant changes to this item. Checks for the reliability of the items in the construct after the principal component analysis showed that they worked particularly well with this sample (see Table 2).

Table 1.

Reliability statistics.

| Variable | Cronbach Alpha Coefficient |

|---|---|

| Comprehensive questionnaire | 0.81 |

| Employees’ perception of workload | 0.68 |

| Comparison of Workload with Colleagues | 0.67 |

| Area of Specialisation | 0.68 |

| Organisation’s staff strength | 0.69 |

| Role mismatches | 0.41 |

Table 2.

Reliability statistics after factor loading.

| Variable | Cronbach Alpha Coefficient |

|---|---|

| Role mismatches | 0.41 |

| 2a: Validity tests | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-CVI | KMO | Bartlett’s Test | Number of Items | Principal Components |

| 0.701 | 0.753 | (P < 0.001) | 15 | 5 |

Structural equation model

Number of obs = 764

Estimation method = ml

Log likelihood = -882.53444

Summary of Results

3.2.2. Validity

The instrument (questionnaire) was constructed by the authors after a careful examination of the constructs used by authors in previous studies. Some of the authors whose works assisted in this respect were Astuti and Navi (2018), Budiman and Putranto (2015), Herminingsih and Kurniasih (2018), Nwinyokpugi (2018), Rajan (2018), Mayasari and Gustomo (2014), Sravani (2018), among others. Astuti and Navi's (2018) article entitled “designing workload analysis questionnaire to evaluate needs of employees” was particularly useful in providing useful direction. The questionnaire was then given to experts in the department of Business studies at Landmark University and the University of Benin for validation prior to pre-testing in a pilot survey. After the experts' validation, the instrument was pretested. The results of the pilot test were analysed using confirmatory factor (principal component) analysis and content validity estimates for validity tests.

Results of the items content validity index (I-CVI) showed that 8 of the items' coefficients were 0.725, 0.715, 0.685, 0.671, 0.712, 0.756, 0.663 and 0.674. Seven of the items had values less than 0.5 and were disregarded. The result of the scale content validity index (S-CVI) of the 8 items was 0.701. Results of the confirmatory factor analysis indicate that the data fit a hypothesized measurement model (constructs) adequately. KMO was 0.753 and the Bartlett's test for Sphericity was significant at one percent level. Five principal components were extracted consistent with the core constructs employed. It was on the basis of the expert judgments, content validity (item and scale level) and principal component analysis that the instrument was deemed adequate for administration and subsequently administered in the main survey.

3.3. Method of data analysis

The data elicited from respondents were coded using SPSS (see Data-Employee Workload). Subsequently, the data were analysed using structural equation modelling. The choice of structural equation modelling was informed by its suitability in analysing problems involving latent variables, bearing in mind that Job satisfaction was treated as a latent variable. Comparison of workload with those of employees, uniqueness of employees' area of specialisation, organisation's staff strength and employees' role alignment served as explanatory variables to employee perception of workload balance while employees' perception of workload balance, organisation's staff strength, uniqueness of employees' area of specialisation, comparison of workload with those of colleagues and employees' role alignment served as explanatory variables for job satisfaction. Organisation's staff strength, uniqueness of employees' areas of specialisation, comparison of workload with those of colleagues and employees' role alignment also served partly as mediating variables between employee perception of workload balance and job satisfaction. Stata software was used to implement the data analysis.

3.3.1. Model specification

The model specifications are given by:

| pwlb = f (oss. cwlc, uasp and rlal). . . | 1 |

| L1 = f (oss, cwlc, uasp, pwlb and rlal); and. . . | 2 |

The models’ equations are:

| pwlb = λ0 + λ1oss + λ2cwlc + λ3 uasp + λ4 rlal. . . | 3 |

| L1 = β0 +β1 oss + β2 cwlc + β3 uasp + β4 pwlb + β5 rlal. . . | 4 |

The structural equation model is:

| Sem (oss cwlc uasp pwlb rlal < - l1). . . | 5 |

where

sem = structural equation model;

oss = organisation's staff strength;

cwlc = comparison of workload with those of colleagues;

uasp = uniqueness of employee's area of specialisation;

rlal = role alignment;

pwlb = Perception of workload balance;

L1 = Job satisfaction (latent variable);

= proportion of the variation in perception of workload balance that is not explained by organisation staff strength, comparison of workload with those of colleagues, uniqueness of employee's area of specialisation and role alignment (oss, cwlc, uasp, and rlal)

(i = 1, 2. . . 4) = slopes of oss, cwlc, uasp, and rlal respectively

= proportion of the variation in job satisfaction that is not explained by organisation staff strength, comparison of workload with those of colleagues, uniqueness of employee's area of specialisation, perception of workload balance and role alignment (oss, cwlc, uasp, pwlb and rlal)

(i = 1, 2. . . 5) = slopes of oss, cwlc, uasp, pwlb and rlal respectively

Eq. (5) is the structural equation model of the study.

3.4. Ethical approval

This sought and got ethical approval from the Landmark University Research Ethical Board.

4. Results

Results of the least square model shows that the computed value of R square is 0.4866, thus indicating that 48.66% of the variation in employees’ perception of workload balance is explained by the explanatory variables organisation staff strength (oss), comparison of workload with those of colleagues (cwlc), uniqueness of area of specialisation (uasp) and role alignment (rlal). The computed F statistic and its associated asymptotic significant probability were 44.07 (p < 0.001), thus indicating that the overall significance of the model is good. The regression coefficients were 0.1969, 0.4903, -0.0017, 0.1196 and 1.0484 for oss, cwlc, uasp rlal and constant respectively. The regression model on the basis of these coefficients is thus:

| pwlb = 1.0484 + 0.1969 oss +0.4903 cwlc – 0.0017 uasp +0.1196 rlal. . . | 4.1 |

Eq. (4.1) indicates that a unit change in organisational staff strength, comparison of workload with those of colleagues, unique area of specialisation and role alignment will lead to 19.69%, 49.03%, 0.17% and 11.96% changes in employees’ perception of workload balance respectively, thus indicating that the most influential predictor is cwlc.

The computed t values and associated significant probabilities are 4.67 (p < 0.001), 7.89 (p < 0.001), -0.03 (0.975), 1.99 (0.048) and 5.27 (p < 0.001) for oss, cwlc, uasp rlal and constant respectively. The implication is that organisation's staff strength and comparison of employee's workload with colleagues are significant at one percent (1%) level while role alignment is significant at five percent (5%) but uniqueness of employee's area of specialisation is not significant. thus, the major factors that influence employees' perception of workload balance are organisation's staff strength, comparison of workload with those of employees and role alignment (See Table 3).

Table 3.

Employee perception of workload balance.

| Source | SS | df | MS | Number of obs = 764 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F(4, 758) = 44.07 | ||||

| Model | 38.9051916 | 4 | 9.72629789 | Prob > F = 0.0000 |

| Residual | 41.0529236 | 759 | .220714643 | R-squared = 0.4866 |

| Adj R-squared = 0.4755 | ||||

| Total | 79.9581152 | 763 | .420832185 | Root MSE = .4698 |

| pwlb | Coef. | Std. Err. | t | P>|t| | [95% Conf. Interval] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| oss | .1968964 | .0421355 | 4.67 | 0.000 | .1137715 | .2800212 |

| cwlc | .4903004 | .0621323 | 7.89 | 0.000 | .3677257 | .6128751 |

| uasp | -.0017206 | .0540919 | -0.03 | 0.975 | -.108433 | .1049918 |

| rlal | .1195918 | .0601253 | 1.99 | 0.048 | .0009766 | .238207 |

| _cons | 1.048371 | .1990646 | 5.27 | 0.000 | .6556561 | 1.441085 |

Results of the structural equation model (SEM) indicate that the computed Z and associated significant probabilities were 1.17 (0.219), 3.95 (p < 0.001), 4.12 (p < 0.001), 1.38 (0.172) and 3.59 (p < 0.001) for uniqueness of employees' area of specialisation (uasp), perception of workload balance (pwlb), comparison of workload with those of employees (cwlc) organisation's staff strength (oss) and role alignment (rlal) respectively. This indicates that perception of workload balance (pwlb), comparison of workload with those of employees (cwlc) and role alignment are significant predictors of job satisfaction at the one percent (1%) level since the asymptotic significant probabilities associated with the tests for these three variables are less than one per cent (0.01), the assumed levels of significance (see Table 4). Uniqueness of employees' area of specialisation (uasp) and organisation's staff strength were found not to be significant since the computed Z and associated significant probabilities were 1.17 (0.219) and 1.38 (0.172) respectively. We may thus conclude, at ninety nine per cent (99%) confidence level that comparison of workload with those of employees, employee perception of workload balance and role alignment are significant predictors of employee job satisfaction.

Table 4.

Employee job satisfaction.

| Variable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latent | Measured Path | Coeff. | Z | Sig. P | Total Effect Results |

| (L1) | uasp | 0.269 | 1.17 | 0.219 | Not supported |

| (L1) | pwlb | 2.450 | 3.95 | 0.000 | supported |

| (L1) | cwlc | 2.236 | 4.12 | 0.000 | supported |

| L1) | oss | 0.423 | 1.38 | 0.172 | Not supported |

| (L1) | rlal | 1.393 | 3.59 | 0.000 | supported |

| Variance | |||||

| e. uasp | 0.3995 | 0.0422 | |||

| e. pwlb | 0.1321 | 0.0293 | |||

| e. cwlc | 0.1726 | 0.0284 | |||

| e. oss | 0.5471 | 0.0631 | |||

| e. rlmm | 0.2987 | 0.0330 | |||

| L1 | 0.0477 | 0.0231 | |||

LR test of model vs. saturated: chi2(5) = 9.45, Prob > chi2 = 0.0925

Results of the goodness of fit test show that the likelihood ratio test had a calculated Chi square value of 9.45 with an associated significant probability of 0.0925. Thus, we cannot reject the hypothesis that a good fit exist since there was no significant difference between the expected and observed matrices. The implication is that the model is a good fit to the data (see Table 5).

Table 5.

estat gof, stats(chi2).

| Fit statistic | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Likelihood ratio | ||

| chi2_ms(5) | 9.448 | model vs. saturated |

| p > chi2 | 0.092 | |

| chi2_bs(10) | 21.855 | baseline vs. saturated |

| p > chi2 | 0.000 | |

The Wald's test for equations show that perception of workload balance (pwlb), comparison of workload with those of colleagues (pwlc) and role alignment (rlal) are all significant at the one percent level while the uniqueness of employee's area of specialisation and organisation's staff strength were not significant (see Table 6). Lastly, the stability analysis of simultaneous equations shows that all the eigenvalues are inside the unit circle and the stability index is 0, thus indicating that the structural adjustment model satisfies stability condition (see Table 7). The results of the Wald's equations test are consistent with the goodness of fit and stability tests (see Table 5). The outcome of the goodness of fit test, which indicate that the structural equation model is a good fit to the data, serves to give credence of the findings with respect to the relationships established between job satisfaction and employee perceptions of workload balance.

Table 6.

Wald’s test for equations.

| chi2 | df | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | |||

| uasp | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| pwlb | 5.61 | 1 | 0.0000 |

| cwlc | 6.94 | 1 | 0.0000 |

| oss | 1.31 | 1 | 0.098 |

| rlal | 12.23 | 1 | 0.0000 |

Table 7.

Stability analysis.

| Stability analysis of simultaneous equation systems. Eigenvalue stability condition | |

|---|---|

| Eigenvalue | Modulus |

| 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 |

stability index = 0

All the eigenvalues lie inside the unit circle.

SEM satisfies stability condition.

4.1. Discussion of findings

The first hypothesis was tested to examine the relationship between employee perception of workload balance and job satisfaction. Results of the structural equation model indicate that there was a positive relationship between employee workload perception and job satisfaction. The positive relationship was significant at one percent level (P < 0.001), which indicates that at ninety nine percent (99%) confidence level, we can conclude that a perception of fair workload enhances job satisfaction while a perception of an unfair workload influences job satisfaction adversely. In other words employee perception of workload influences job satisfaction. The results are consistent with Herminingsih and Kurniasih (2018) and Liu and Lo (2018) and partly with the findings of De Cuyper and De Witte (2006).

The second hypothesis was tested to examine the relationship between uniqueness of employee's area of specialization and perception of workload balance. Results of the regression analysis indicate that there was a positive relationship between the uniqueness of respondent's area of specialization and employee perception of workload. The relationship was insignificant at five percent level (P = 0.975), which means that at ninety five percent (95%) confidence level, we can conclude that uniqueness of area of specialization does not have any significant influences on employee perception of workload. this tends to suggest that the respondents' jobs are not highly specialised. The results are inconsistent with those of Ford (2012) as well as Ford and Jin (2015).

The third hypothesis was tested to examine the relationship between comparison of workload with those of colleagues and employees' perception of workload balance. Results of the regression analysis indicate that there was a significant positive relationship between employees’ comparison of workload with those of colleagues and their perception of workload balance. The positive relationship indicates that when employees perceive a high level of fairness in workload among organisational members, they tend to perceive the degree of workload balance as high in the organisation and vice versa. The results are consistent with equity theory.

The fourth hypothesis was tested to examine the relationship between job role alignment and employee perception of workload balance. Results of the regression analysis indicate that there was a positive relationship between job role alignment and perception of workload balance. The positive relationship was significant at one percent level (P < 0.001), thus, at ninety nine percent (99%) confidence level, we can conclude that job role alignment has a significant positive influence on employees' perception of workload balance. This means that the more one's job role aligns with his competencies and capacity the more interested he will be and the higher his perception of workload balance because he will have fulfilment in the job. The results are supported by Nwinyokpugi (2018) and Malta (2004).

The fifth hypothesis was tested to examine the relationship between job role alignment and job satisfaction. Results of the regression analysis indicate that there was a positive relationship between job role alignment and job satisfaction. The positive relationship was significant at one percent level (P < 0.001), thus, at ninety nine percent (99%) confidence level, we can conclude that employees' job role alignment has a significant positive influence on job satisfaction. This means that the more one's job role aligns with his competencies and capacity the more interested he will be and the higher his level of satisfaction owing to his fulfilment in the job. The results are supported by Nwinyokpugi (2018) and Malta (2004).

The sixth hypothesis was tested to find out whether there is a significant relationship between organisation’ staff strength and employee perception of workload imbalance. Results of the structural equation model indicate that there was a positive relationship between organisation's staff strength and employees' perception of workload balance. The positive relationship was significant at one percent level (P < 0.001), which indicates that at ninety nine percent (99%) confidence level, we can conclude that organisation's staff strength significantly influences employees' perception of workload balance. Thus, the feeling that the organisation is adequately staffed helps to reduce the perception of workload imbalanced and enhance the perception of workload balance. The results are supported by Nwinyokpugi (2018).

4.2. Proposed model of employee perception of workload balance and job satisfaction

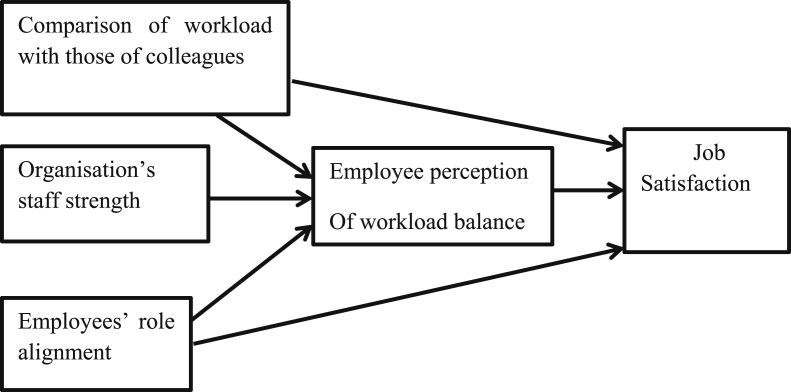

Based on the research findings, a model of employee perception of workload balance and job satisfaction, which explains some of the factors that influence employees' perception of workload balance and how employees' perception of workload balance influences job satisfaction is proposed. The proposed model shows that three major factors (employees' comparison of workload with those of colleagues, organisation's staff strength and employees' role alignment) significantly influence employees' perception of workload balance and two of these factors (employees' comparison of workload with those of colleagues and role alignment) have significant influence on job satisfaction. Also, employee perception of workload balance has significant impact on job satisfaction (see Figure 1). The results are consistent with Herminingsih and Kurniasih (2018) and Liu and Lo (2018) but partially consistent with De Cuyper and De Witte (2006) findings that workloads are significant predictors of job satisfaction The relationships in the proposed model are partly consistent with comparison process theory and social influence hypothesis which constituted the framework of the study.

Figure 1.

Proposed model of employee perception of workload and job satisfaction.

4.3. Implication of findings

Results of this study have significant implications for managers. Job satisfaction is critical to employee productivity and turnover in an organisation. But employee perception of workload balance influences job satisfaction which means that, invariable, employee perception of workload is critical to organisational productivity and turnover. For management to minimise the problems associated with employee turnover and productivity, the need to prioritise equitable job designs and workload management to minimize the discrepancies between normal, low and high workloads becomes imperative. While there is a tendency for strategic managers to focus on cost reduction in all fronts, including labour costs, with a view to maximising profits, there is a limit to the extent to which cost can be reduced. There is a minimum benchmark for input requirements for every production target. The same is applicable to manpower requirements and employee workload. Adequate workload management will help to enhance perception of workload balance as well as reduce the perception of discrepancies associated with comparison of workload with those of colleagues and thus enhance job satisfaction.

5. Conclusions

The research conclusions are as follows:

Employees' perception of workload balance influences their satisfaction. Furthermore, comparison of workload with those of colleagues and employees' role alignment influence their perception of workload balance and job satisfaction while organisation's staff strength influences employee workload balance.

This study has made significant contribution to knowledge in management and social science research as well as in psychology. While there are numerous studies on employee workload, none of the studies appears to have investigated the relationship between employees’ comparison of workload with those of colleagues with their perception of workload balance and job satisfaction. This study has shown that when employees compare their workload with other employees of the same status or those on higher income level and feel that they have higher workload they feel dissatisfied. Furthermore, the proposed model of employee perception of workload balance and job satisfaction will prove useful to policy makers, strategic managers and other stakeholders committed to building successful organisations.

The study encountered some limitations which suggest the need for further studies in this area. Firstly, the authors sought for data on employee workload in some organisations but the management of the organisations were not forthcoming with such data. This informed the use of data on employees' perception of workload. Secondly, the study focused mainly on multinational companies operating in Nigeria aside the two private Nigerian universities. Since the organisational cultures of multinational companies differ from those of most national companies, it would have been instructive to study national companies or even make a comparison between multinational and national companies. Lastly, employee workload perception is investigated without recourse to some factors that may serve to attract the employees’ interest in the organisation. There may be other factors that may cause employees to perceive workload imbalance in an organisation which were not considered, like faulty equipment.

5.1. Recommendations

Employee workload balance is very important because of the consequences of excess workload on employee health and psychology. Given the fact that employee perception of workload balance influences their job satisfaction and that job satisfaction is crucial to employee turnover and performance, the need for strategic managers to be concerned about workload balancing and employees’ perception of workload balancing becomes sacrosanct. To this end, the following recommendations are suggested: Policy makers in government and strategic managers should design jobs in a manner that will minimise discrepancies in workloads across organisational status. This requires that deliberate efforts be made, where possible, to balance workload to make the employees have a sense of fairness. Where workload balance is not possible, the discrepancies between workloads should be significantly minimised and employees must be carried along in this respect.

Organisational stakeholders should also ensure that job roles of employees align with their competencies and capabilities. This will enhance the chances that employees will be interested in their jobs and thus be more likely to have fulfilment in doing the job and less likely to perceive workload imbalance. Inclusion of psychological test in recruitment interviews will prove useful in this regard. Furthermore, stakeholders should, as much as possible, engage adequate hands to man the various job roles in the organisation through effective manpower requirements planning. This will help to avoid overloading employees with work. If employees, for any reason, happen to discharge more duties than they are supposed to, then they should be adequately compensated for such extra workload pending such a time that the organisation is able to engage additional employees.

Lastly, critical stakeholders in organisations should constantly review workload balance as a matter of priority concern in their organisations. This will help to ensure that workload imbalance is brought to the attention of management at the earliest possible time for appropriate action rather than allowing it cause dissatisfaction among the employees.

Future studies should seek data on employee workloads from specific organisations for analysis to enable them make inference on employee workload balance in organisations on the basis of theoretical maximum workload assignable. Secondly, the study concentrated more on multinational companies because of the need to give the study some degree of international coloration. Since the organisational cultures and management structures of multinational companies seem to differ from what obtains in most national companies. Future studies should try to investigate national companies alone or, better still, compare national companies with multinational companies to find out whether the results will be consistent or inconsistent with the findings of this study. Lastly, future studies should investigate the attractions in respondents’ organisations that may make them to remain loyal to their organisations despite the perception of workload imbalance by some of them.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Henry Egbezien Inegbedion: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Emmanuel Edo Inegbedion: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Adeshola Peter, Lydia Harry: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- Akobo M. Influence of workload, work ethic and job satisfaction towards teachers’ performance: a study of Islamic based school in Makasar Indonesia. Glob. Adv. Res. J. Manag. Bus. Stud. 2016;5(7):172–177. [Google Scholar]

- Ali S., Farooqi Y.A. Effect of work overload on job satisfaction, effect of job satisfaction on employee performance and employee engagement (a case of public sector University of Gujranwala Division) Int. J. Multidiscip. Sci. Eng. 2014;5(8):23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Astuti R.D., Navi N.A. AIP Conference Proceedings. Vol. 1931. 2018. Designing workload analysis questionnaire to evaluate needs of employees; p. 30027. (2018) [Google Scholar]

- Briggs R.B. Problems of recruitment in civil service: case of the Nigerian civil service. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2007;1(6):142–153. [Google Scholar]

- Budiman Y., Putranto N.A.R. Workload analysis for planning needs of employee in Pt. Batuwangi Putera Sejahtera. J. Bus. Manag. 2015;4(4):494–500. [Google Scholar]

- Chen T., Wu K., Lin W., Horna W., Shieh C. 2013. Incorporating Workload and Performance Levels into Work Situation Analysis of Employees with Application to a Taiwanese Hotel Chain. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta P.R. Volatility of workload on employee performance and significance of motivation: IT sector. J. Bus. Manag. 2013;1(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- De Cuyper N., De Witte H. Autonomy and workload among temporary workers: their effects on job satisfaction, organizational commitment, life satisfaction, and self-rated performance. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2006;13(4):441–459. [Google Scholar]

- Erat S., Kitapci H., Comez P. The effect of organizational loads on work stress, emotional commitment and turnover intention. Int. J. Organ Leadersh. 2017;6:221–231. [Google Scholar]

- Ford M.T. Job-occupation misfit as an occupational stressor. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012;80:412–421. [Google Scholar]

- Ford M.T., Jin J. Incongruence between workload and occupational norms for time pressure predicts depressive symptoms. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2015;24(1):88–100. [Google Scholar]

- Hart S.G., Staveland L.E. Development of NASA-TLX (task load index): results of empirical and theoretical research. In: Hancock P., Meshkati N., editors. Human Mental Workload; North-Holland: 1998. pp. 139–183. [Google Scholar]

- Herminingsih A., Kurniasih A. The influence of workload perceptions and human resource management practices on employees’ burnout. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2018;10(21):19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hombergh P., Kunzi B., Elwyn G. High workload and job stress are associated with lower practice performance in general practice: an observational study in 239 general practices in The Netherlands. Health Serv. Res. 2009;9(118):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igbokwe-Ibeto C.J., Agbodike F., Osawe C. Work content in the Nigerian civil service and its implication on sustainable development. Singaporean J. Bus. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2015;4(4):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Inegbedion H.E. Factors that influence customers' attitude toward electronic banking in Nigeria. J. Internet Commer. 2018;17(4):325–338. [Google Scholar]

- Inegbedion H.E., Obadiaru E. Modelling brand loyalty in the Nigerian telecommunications industry. J. Strateg. Mark. 2019;27(7):583–598. [Google Scholar]

- Inegbedion H.E., Obadiaru D.E., Bello D.V. Factors that influenceconsumers' attitude towards internet buying in Nigeria. J. Internet Commer. 2016;15(4):353–375. [Google Scholar]

- Lea V.M., Corlett S.A., Rodgers R.M. Workload and its impact on community pharmacists' job satisfaction and stress: a review of the literature. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2012;20(4):259–271. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7174.2012.00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H.L., Lo V. An integrated model of workload, autonomy, burnout, job satisfaction, and turnover intention among Taiwanese reporters. Asian J. Commun. 2018;28(2):153–169. [Google Scholar]

- Locke E.A. What is job satisfaction? Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1969;4(4):309–336. [Google Scholar]

- Malta Management standards and work-related stress in the UK: policy background and science. Work Stress. 2004;18(2):89–185. Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Mayasari M., Gustomo A. Workload analysis on CV.SASWCO PERDANA. J. Bus. Manag. 2014;3(6):673–681. [Google Scholar]

- Nwinyokpugi P. Workload management strategies and employees efficiency in the Nigerian banking sector. Int. J. Innov. Res. Dev. 2018;7(1):286–293. [Google Scholar]

- Portoghese I., Galletta M., Coppola R.C., Finco G., Campagna M. Burnout and workload among health care workers: the moderating role of job control. Saf. Health Work. 2014;5(3):152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.shaw.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi M.I., Iftikhar M., Abbas S.G. Relationship between job stress, workload, Environment and turnover intentions: what we know, what should we know. World Appl. Sci. J. 2013;23(6):764–770. [Google Scholar]

- Rahim M.S., Saat N.Z.M., Aishah H.S. Relationship between academic workload and stress level among biomedical science students in Kuala Lumpur. J. Appl. Sci. 2016;16(1):108–112. [Google Scholar]

- Rajan D. Negative impacts of heavy workloads: a comparative study among sanitary workers. Sociol. Int. J. 2018;2(6):465–474. [Google Scholar]

- Salancik G.R., Pfeffer J. An examination of need-satisfaction models of job attitudes. Adm. Sci. Q. 1977:427–456. [Google Scholar]

- Smith P.C., Kendall L.M., Hulin C.L. Rand Mcnally; Oxford, England: 1969. The Measurement of Satisfaction in Work and Retirement: A Strategy for the Study of Attitudes. [Google Scholar]

- Sravani A. Managing the distribution of employee workload of the hospital staff. IJRDO J. Bus. Manag. 2018;4(1):40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ukaegbu C.C. Work content in the Nigerian civil service. Niger. J. Public Adm. Local Govern. 1995;6(1):44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Bossche R., Vanmechelen K., Broeckhove J. 2010 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Cloud Computing. 2010. Cost-optimal scheduling in hybrid iaas clouds for deadline constrained workloads; pp. 228–235. [Google Scholar]

- Vroom V.H. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 1964. Work and Motivation. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss H., Shaw J. Social influences on judgments about tasks. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1979;24:126–140. [Google Scholar]

- White S.E., Mitchell T.R. Job enrichment versus social cues: a comparison and competitive test. J. Appl. Psychol. 1979;64(1):1. [Google Scholar]

- Xiaoming Y., Ma B.J., Chang C. Effects of workload on burnout and turnover intention of medical staff. J. Ethno-Med. 2014;8(3):229–237. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.