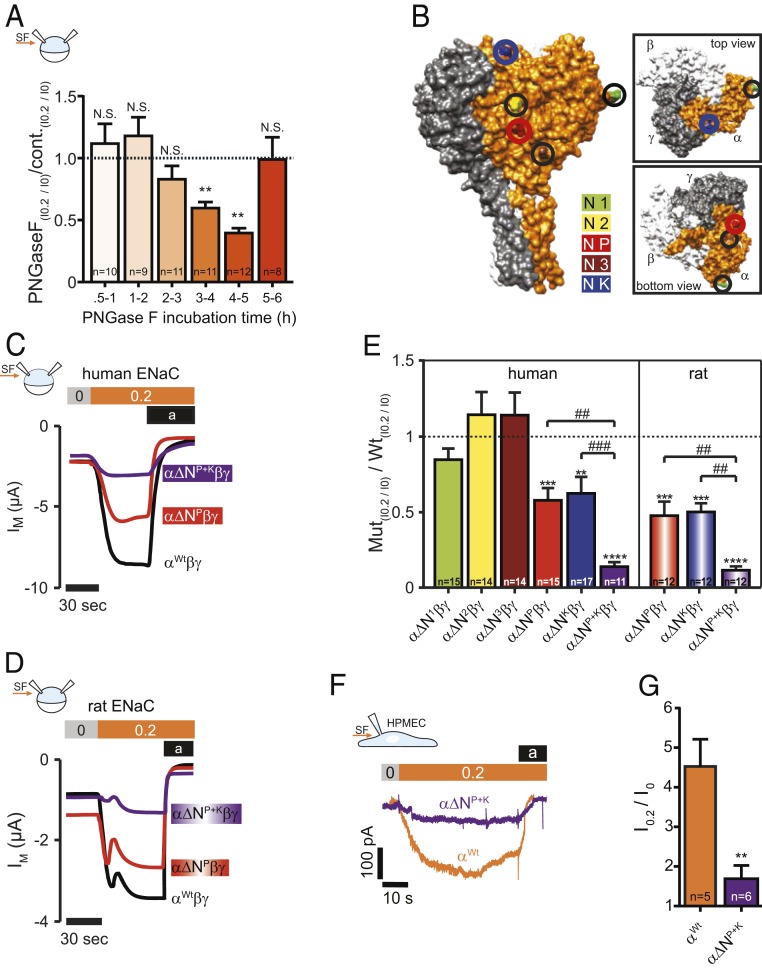

Fig. 3.

N-linked glycans and glycosylated asparagines contribute to the SF-effect. (A) Injection of PNGase F into the oocytes resulted in a time-dependent reduction of the SF-mediated response (mean ± SEM; **P < 0.01, N.S., not significant, one-sample t test, two-tailed). (B) Surface structure of a human α-, β-, γENaC-heterotrimer displaying the localization of glycosylated asparagines of αENaC. (C) Current-traces of the SF-effects in oocytes that express human or (D) αβγENaC Oocytes expressed either a wild-type (Wt) αENaC (black trace) or αENaC that had a single asparagine replaced in the palm domain (α∆NP, red trace) or two asparagines replaced (in palm and knuckle domain: α∆NP+K, purple trace). (E) Replacement of asparagines of human and rat αENaC in the palm and knuckle domains decreased the SF response. Dashed line represents SF responses from corresponding control experiments using either human or rat wild-type αβγENaC (mean ± SEM; ****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, one-sample t test, two-tailed; ###P < 0.001. ##P < 0.01 and as indicated, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni´s multiple comparison test). (F) Representative current-traces of HPMECs exposed to SF (0.2 dyn/cm2, orange bar). Amiloride (a, black bar) was applied to estimate ENaC-mediated currents. Compared to wild-type HPMECs (αWt, orange current trace), CRISPR/Cas9-mediated replacement of the asparagines in the palm and knuckle domains of αENaC (α∆NP+K, purple trace) blunted the SF-induced increase in current in these cells. (G) Statistical analysis from experiments depicted in F. **P < 0.01, unpaired t test, two-tailed.