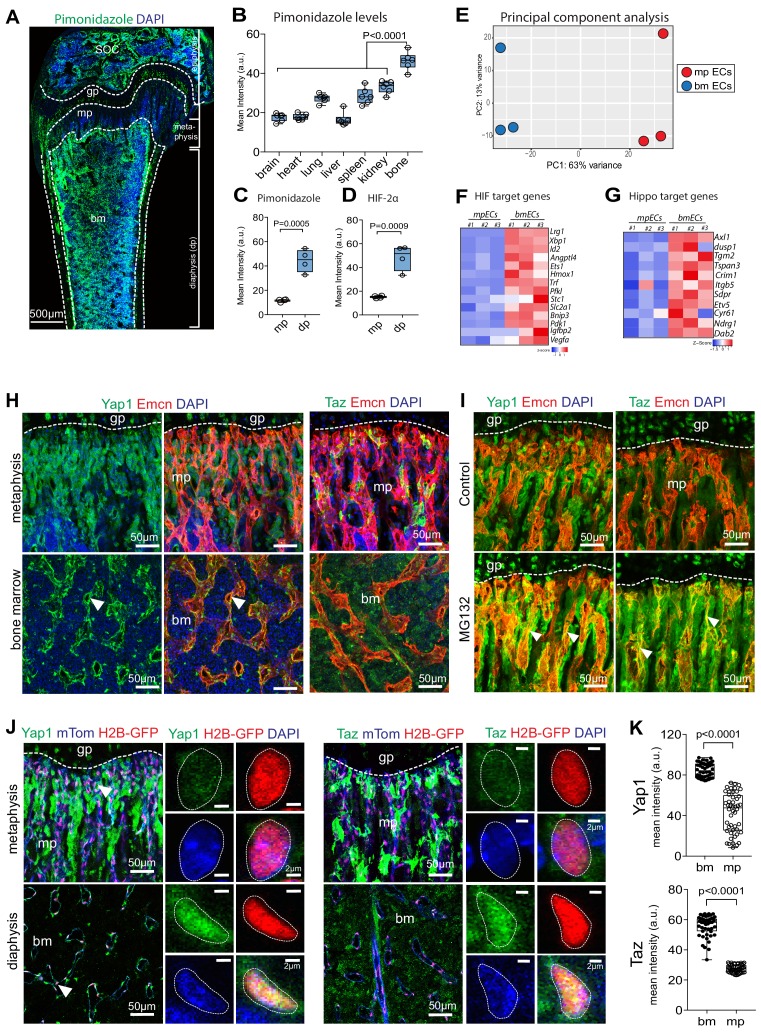

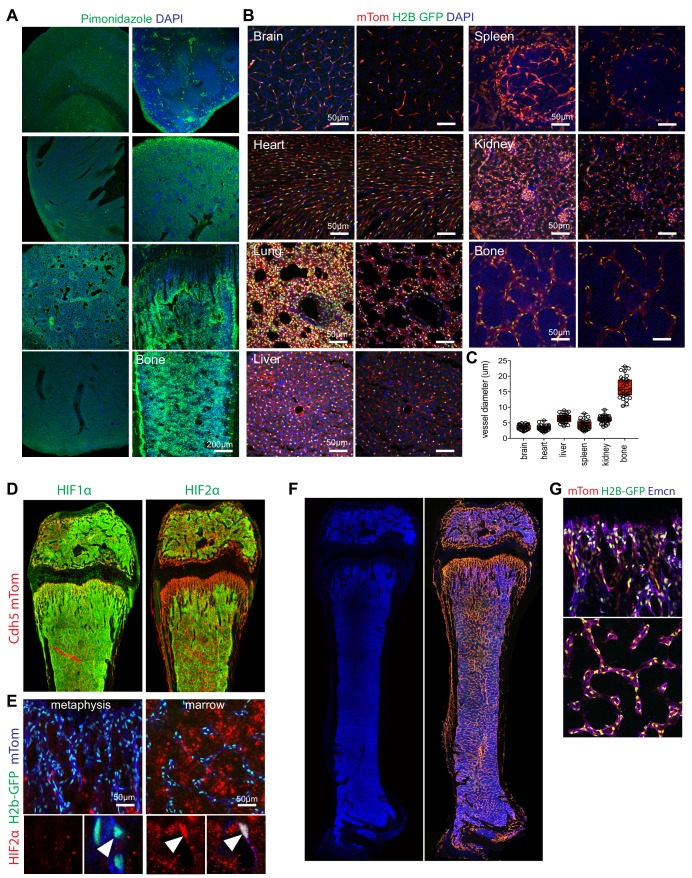

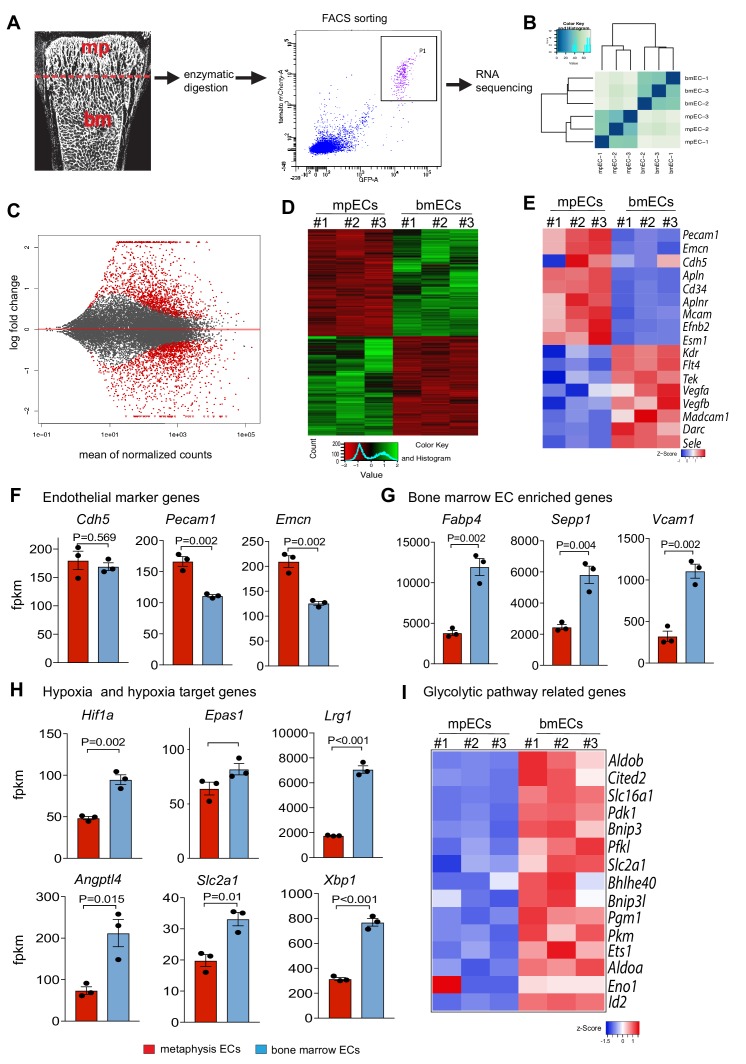

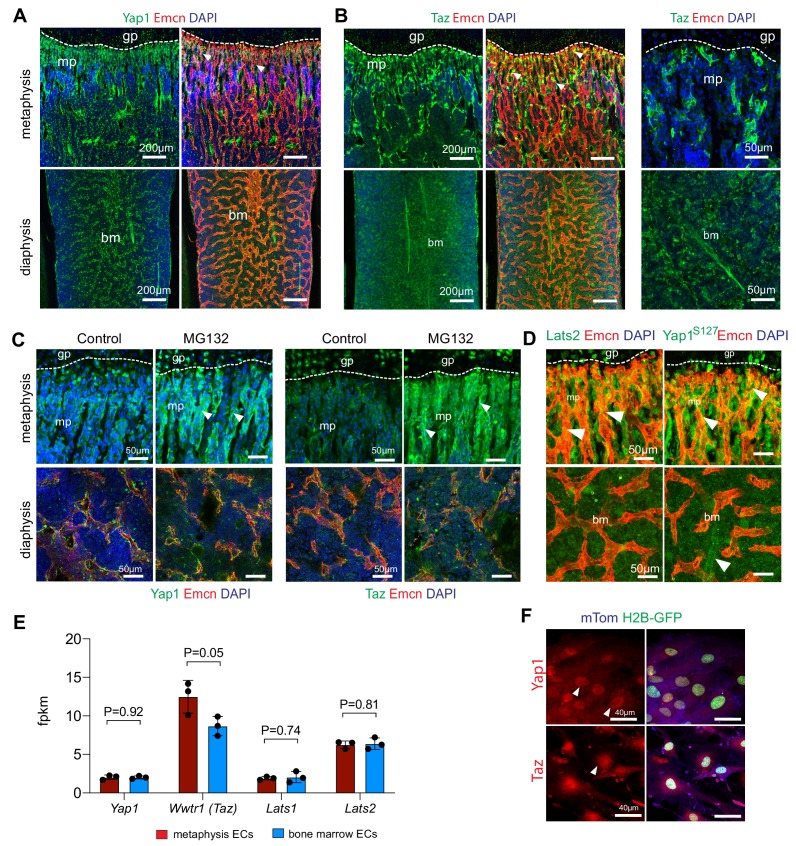

Figure 1. Regional differences in hypoxia and Yap1/Taz expression in bone.

(A) Tile scan maximum intensity projection of P21 femur with Pimonidazole (green) and DAPI (blue) staining. (B) Quantification of Pimonidazole staining intensity (artificial units, a.u.) in different organs. (C, D) Regional differences in Pimonidazole (C) and HIF2α (D) staining levels in metaphysis (mp) and diaphysis (dp). (E) Principal component analysis of RNA sequencing data using most variable genes across the samples. The first principal component (PC1) explains 63% of all variance; and PC2 13% of the variance between metaphyseal (mpECs) and diaphyseal/bone marrow (bmECs) endothelial cells. (F, G) Heat map showing differential expression of hypoxia (F) and Yap1/Taz (G) controlled genes in mpECs vs. bmECs. (H) Confocal image showing immunostaining of Yap1 and Taz (H) in 3-week-old wild-type femur. Arrowheads highlight expression in Emcn+ (red) ECs. Nuclei, DAPI (blue). (I) Immunostaining of Yap1 and Taz in the control (vehicle) and MG132 proteasome inhibitor-treated femoral metaphysis. (J) Nuclear localization (arrowheads) of Yap1 (green) in H2B-GFP+ EC nuclei (shown in red) in 3-week-old Cdh5-mTnG femoral metaphysis (mp) and bone marrow (bm). Higher magnification image shows strong Yap1 and Taz nuclear signals bmECs. (K) Mean intensity (a.u.) of Yap1 and Taz nuclear localization signals in bm and mp ECs. (n = 4; 48 cells in total; data are presented as mean ±sem, P values, two-tailed unpaired t-test).