Abstract

We report 281 individuals carrying a pathogenic recurrent NF1 missense variant at p.Met1149, p.Arg1276, or p.Lys1423, representing three nontruncating NF1 hotspots in the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) cohort, together identified in 1.8% of unrelated NF1 individuals. About 25% (95% confidence interval: 20.5–31.2%) of individuals heterozygous for a pathogenic NF1 p.Met1149, p.Arg1276, or p.Lys1423 missense variant had a Noonan‐like phenotype, which is significantly more compared with the “classic” NF1‐affected cohorts (all p < .0001). Furthermore, p.Arg1276 and p.Lys1423 pathogenic missense variants were associated with a high prevalence of cardiovascular abnormalities, including pulmonic stenosis (all p < .0001), while p.Arg1276 variants had a high prevalence of symptomatic spinal neurofibromas (p < .0001) compared with “classic” NF1‐affected cohorts. However, p.Met1149‐positive individuals had a mild phenotype, characterized mainly by pigmentary manifestations without externally visible plexiform neurofibromas, symptomatic spinal neurofibromas or symptomatic optic pathway gliomas. As up to 0.4% of unrelated individuals in the UAB cohort carries a p.Met1149 missense variant, this finding will contribute to more accurate stratification of a significant number of NF1 individuals. Although clinically relevant genotype–phenotype correlations are rare in NF1, each affecting only a small percentage of individuals, together they impact counseling and management of a significant number of the NF1 population.

Keywords: genotype–phenotype correlation, NF1, p.Arg1276, p.Lys1423, p.Met1149

1. INTRODUCTION

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1; MIM# 162200) is one of the most common autosomal dominant disorders with a birth incidence of 1 in 2,000–3,000 (Evans et al., 2010; Lammert, Friedman, Kluwe, & Mautner, 2005; Uusitalo et al., 2015). It is characterized by a highly variable expressivity and age‐dependent clinical features, including multiple café‐au‐lait macules (CALMs), skinfold freckling, Lisch nodules, cutaneous, plexiform and/or spinal neurofibromas, optic pathway gliomas (OPGs), neoplasms, skeletal abnormalities, and learning difficulties. The wide range of variable expression makes genetic counseling and anticipatory guidance challenging (Friedman, 2014).

NF1 results from loss‐of‐function pathogenic variants in the NF1 tumor suppressor gene (MIM# 613113), located on chromosome 17q11.2, a locus with one of the highest spontaneous mutation rates across single‐gene human genetic disorders (Friedman, 2014; Huson, Compston, Clark, & Harper, 1989). Indeed, the extreme diversity of the NF1 mutational spectrum observed in the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) cohort of approximately 8,000 unrelated NF1‐affected individuals, all comprehensively analyzed with NF1 transcript analysis, includes greater than 3,000 different constitutional variants, with only 31 having a prevalence of ≥0.4% (Messiaen & Wimmer, 2012; Messiaen, in preparation). The constitutional NF1 microdeletion represents the most frequent recurrent pathogenic variant (~3–8%) and therefore was first recognized to have a genotype–phenotype association with a distinct severe form of NF1 (Kehrer‐Sawatzki, Mautner, & Cooper, 2017). Nontruncating pathogenic variants affecting only a single amino acid are more likely to be associated with genotype–phenotype correlations, as they may represent gain‐of‐function or hypomorphic variants. Although missense variants contribute to approximately 17% of all variants found in unrelated NF1‐affected individuals in the UAB cohort, very few are recurrent and therefore amenable to variant‐specific genotype–phenotype analyses. Indeed, only six true nontruncating hotspots, each with a prevalence ≥0.4%, were found in the UAB cohort, i.e., missense variants at codons 844‐848, 1149, 1276, 1423, and 1809 and a single amino acid deletion p.Met992del (Figure 1). To date, genotype–phenotype associations affecting pathogenic missense variants at NF1 codons 1809 and 844‐848 and p.Met992del have been reported, representing approximately 1.2, 0.8, and 0.9% of unrelated probands, respectively (Koczkowska et al., 2018; Koczkowska et al., 2019; Pinna et al., 2015; Rojnueangnit et al., 2015; Upadhyaya et al., 2007). Increased efforts towards the identification of additional clinically relevant genotype–phenotype correlations are needed. Therefore, we examined with priority those individuals carrying a pathogenic variant at one of the three remaining nontruncating hotspots, i.e. at p.Met1149, p.Arg1276 and p.Lys1423.

Figure 1.

Spectrum of six mutational hotspots at NF1 codons 844‐848 (67/8,000), 992 (74/8,000), 1149 (34/8,000), 1276 (57/8,000), 1423 (52/8,000), and 1809 (99/8,000), affecting a total of 383/8,000 (4.8%) of unrelated probands in the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) cohort, associated with mild (upper panel) or severe (lower panel) phenotypes. The figure was prepared using ProteinPaint application (Zhou et al., 2016). CSRD, cysteine‐serine rich domain; GAP, GTPase‐activating protein; GRD, GAP related domain; NF1, neurofibromatosis type 1; PH, pleckstrin homology‐like domain; Sec14, Sec14 homology‐like domain; Syn, syndecan binding domain; TBD, tubulin‐binding domain

In this cross‐sectional study, we investigated the clinical spectrum of 281 individuals from 237 unrelated families identified through clinical genetic testing as being heterozygous for a missense variant at p.Met1149, p.Arg1276, or p.Lys1423.

2. METHODS

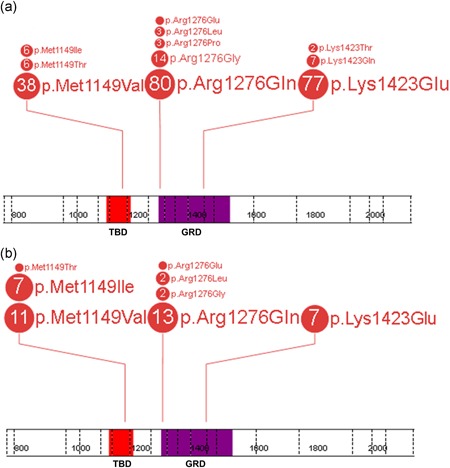

In total, 237 unrelated probands and 44 relatives, all carrying a pathogenic NF1 missense variant at either p.Met1149 (50 probands and 19 relatives), p.Arg1276 (101 probands and 18 relatives), or p.Lys1423 (86 probands and 7 relatives), were included in this study (Figure 2). Briefly, blood samples from 220 individuals (184 probands and 36 relatives) were originally sent to the Medical Genomics Laboratory at the UAB for molecular NF1 genetic testing to establish or confirm the diagnosis of NF1. Two individuals from the UAB cohort, carrying c.3445A>T (p.Met1149Leu) and c.4268A>T (p.Lys1423Met) were excluded from the genotype–phenotype studies as these specific variants are still interpreted as “variant of uncertain significance” (VUS) or “likely pathogenic”, respectively, but not (yet) “pathogenic”, according to the here applied American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) recommendations (Richards et al., 2015). This initial study was expanded to include an additional 63 individuals (55 probands and 8 relatives), molecularly diagnosed in collaborating institutions (please see details in the Supporting Information Methods). The collaborating institutions and their referring physicians completed the same phenotypic checklist and as they did not have prior insight into the phenotypic associations emerging from the UAB cohort, their contributions were independent and unbiased. All variants identified in this study with the confirmed origin of the variants were submitted to the LOVD and ClinVar databases.

Figure 2.

Spectrum of pathogenic NF1 missense variants affecting p.Met1149, p.Arg1276, and p.Lys1423 in the studied cohort of 237 unrelated probands (a) and 44 relatives (b). Each number in the circle corresponds with the total number of individuals heterozygous for a specific variant. The figure was prepared using the ProteinPaint application (Zhou et al., 2016). GAP, GTPase‐activating protein; GRD, GAP related domain; NF1, neurofibromatosis type 1; TBD, tubulin‐binding domain

Comprehensive NF1 molecular analysis, interpretation of variant pathogenicity and collection of clinical data (see details in Supporting Information Methods) was performed as previously described (Koczkowska et al., 2018; Koczkowska et al., 2019; Messiaen et al., 2000; Richards et al., 2015; Rojnueangnit et al., 2015). Two‐tailed Fisher's exact test with p < .05 considered as statistically significant was applied. The resulting p values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini–Hochberg (B‐H) procedure with false discovery rates (FDR) at 0.05 and 0.01 (Thissen, Steinberg, & Kuang, 2002). These statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad software. The risk ratio was calculated with the STATCALC module from the Epi InfoTM package version 7.2.3.1 (http://cdc.gov/epiinfo/index.html).

This study was approved by the UAB Institutional Review Board and all individuals participating in this study or their legal guardians signed the informed consent forms for clinical genetic testing.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Description of the NF1 missense variants affecting p.Met1149, p.Arg1276, and p.Lys1423

The pathogenic missense variants described here were identified in approximately 0.4% (p.Met1149), 0.7% (p.Arg1276), and 0.7% (p.Lys1423) of probands, together affecting 1.8% (95% confidence interval: 1.5–2.1%) of unrelated NF1 individuals in the UAB cohort.

Twelve different missense variants (representing 14 different substitutions) at codons 1149, 1276, or 1423 are reported here in 237 unrelated individuals, with only 8/12 present in disease‐associated public databases (as of December 2018; Figure S1) and 2/12 reported in ≥245,936 alleles in the control Genome Aggregation database (gnomAD; Tables S1–S3).

RNA‐based sequencing indicated that three substitutions at NF1 codon 1423, involving the last three nucleotides of exon 32 (24), were associated with in‐frame exon 32 (24) skipping during NF1 messenger RNA splicing (Table S4) and therefore were classified as splicing variants, not true missense.

All variants described in this study were classified according to the ACMG recommendations (Richards et al., 2015), with only pathogenic missense variants included in the genotype–phenotype study (Table S5).

3.2. Clinical characterization of the p.Met1149‐positive cohort

Detailed clinical descriptions of 70 individuals from 51 different families heterozygous for one of four different pathogenic NF1 amino substitutions at p.Met1149 (38 probands with c.3445A>G [p.Met1149Val], a single proband with c.3445A>T [p.Met1149Leu], six probands with c.3446T>C [p.Met1149Thr] and six probands with c.3447G>A/C/T [p.Met1149Ile]) are presented in Tables S6 and S7 and Figure S2. UAB‐R1495, carrying c.3445A>T (p.Met1149Leu), was excluded from the genotype–phenotype study as the interpretation of this specific variant is “variant of uncertain significance” according to the ACMG recommendations (see details in Table S5).

p.Met1149‐positive individuals ≥9 years presented with a mild phenotype, including multiple CALMs (41/46) and skinfold freckles (29/44). Lisch nodules were reported in 3/29 individuals ≥9 years. No externally visible plexiform or symptomatic spinal neurofibromas were seen in this cohort (0/42 and 0/41 ≥ 9 years, respectively), except for an 18‐year‐old girl (UAB‐R2593) having one possible spinal lesion with differential diagnosis of spinal neurofibroma versus cyst. Four of 22 adults reportedly had 2–6 cutaneous and/or subcutaneous neurofibromas, but none had been biopsied and histopathologically confirmed (Table S6). No symptomatic or asymptomatic OPG was found in all 58, including 23 individuals who underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) screening. Other benign neoplasms reported in this cohort (10.5%, 6/57) included lipomas (n = 4), pilomatrixoma (n = 1), and a lesion in the right temporal lobe (n = 1). The prevalence of skeletal abnormalities, mainly pectus abnormalities (n = 8) was 24.6% (15/61). Short stature and macrocephaly were observed in 15.2% and 42.2% of cases, respectively. Thirty‐one p.Met1149‐positive individuals had cognitive impairment and/or learning disabilities (47%, 31/66). Although a high number of individuals with Noonan‐like features (29%) was reported (Table S8), pulmonic stenosis (PS) was found only in two individuals (UAB‐R9777 and UAB‐R13811FN.405). Other cardiovascular abnormalities included atrial septal defect (n = 2), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (n = 1), and quadricuspid aortic valve (n = 1). Finally, 4/24 (16.7%) cases ≥9 years with a completed phenotypic checklist did not fulfill the National Institute of Health (NIH) diagnostic criteria and 6/24 (25%) when family history was excluded as a criterion (Table S9).

3.3. Clinical characterization of the p.Arg1276‐ and p.Lys1423‐positive cohorts

Detailed clinical descriptions of 119 individuals from 101 different families heterozygous for one of five different pathogenic NF1 amino acid substitutions at p.Arg1276 (14 probands with c.3826C>G [p.Arg1276Gly], a single proband with c.3826_3827delinsGA [p.Arg1276Glu], 80 probands with c.3827G>A [p.Arg1276Gln], three probands with c.3827G>C [p.Arg1276Pro], and three probands with c.3827G>T [p.Arg1276Leu]) and 94 individuals from 87 different families heterozygous for one of four different pathogenic NF1 amino substitutions at p.Lys1423 (seven probands with c.4267A>C [p.Lys1423Gln], 77 probands with c.4267A>G [p.Lys1423Glu], two probands with c.4268A>C [p.Lys1423Thr], and a single proband with c.4268A>T [p.Lys1423Met]) are presented in Tables S10–S13 and Figures S3 and S4. UAB‐R1753, carrying c.4268A>T (p.Lys1423Met), was excluded from the genotype–phenotype study as the interpretation of this specific variant is “likely pathogenic” according to the ACMG recommendations (see details in Table S5).

Individuals carrying p.Arg1276 or p.Lys1423 pathogenic missense variants presented with more severe phenotypes compared with the p.Met1149‐positive cohort (Tables S11–S13). The most striking feature associated with p.Arg1276 was the presence of symptomatic spinal neurofibromas (18/97, 18.6% all ages). As many as 17/36 (47.2%) adults (≥19 years) had symptomatic spinal tumors and an additional 4/11 (36.4%) had multiple tumors on spinal roots without clinical symptoms (Table S14). A very high load of symptomatic or asymptomatic spinal neurofibromas, but few cutaneous neurofibromas and/or pigmentary manifestations, characteristic for so‐called spinal NF, was seen in 5/21 adults (Figure S5), including one proband with a family history of spinal NF (UAB‐R743). The p.Lys1423 cohort was characterized by a high prevalence of externally visible plexiform neurofibromas compared with the p.Arg1276 cohort (15/48 vs. 5/64 in ≥9 years; p = .0022; Tables S16–S18), but a lower prevalence of symptomatic spinal tumors (3/65 vs. 18/97 all ages; p = .0091; Tables S14, S15, and S18). Furthermore, 82.1% of adults with p.Lys1423 (23/28), but only 35% with p.Arg1276 (14/40) had ≥2 cutaneous neurofibromas (p = .0002; Table S18).

The prevalence of CALMs and skinfold freckling was similar in both cohorts (Tables S11 and S13). Lisch nodules were more frequently reported in the p.Lys1423‐positive individuals (52.5%, 31/59) compared with the p.Arg1276‐positive cases (24.1%, 19/70). Despite the severe phenotypes observed in p.Arg1276‐positive cases, 3/31 individuals ≥9 years with a complete phenotypic checklist did not fulfill the NIH diagnostic criteria after excluding family history (Table S19).

Symptomatic OPGs were not found in the p.Arg1276‐positive individuals (0/97) and were rare in the p.Lys1423 cohort (1/74; EUR‐R49). An asymptomatic OPG was identified by MRI screening in 1/48 (2.1%) p.Arg1276‐positive and 6/40 (15%) p.Lys1423‐positive individuals. Neoplasms, other than OPGs and neurofibromas, were observed in 8/94 (8.5%) of the p.Arg1276‐positive and 11/77 (14.3%) p.Lys1423‐positive individuals, including 4/8 and 7/11, respectively who developed malignant lesions (Tables S10–S12).

Similarly to the p.Met1149 cohort, Noonan‐like features were frequently reported in the p.Arg1276‐ and p.Lys1423‐positive individuals (22/106 and 24/83, respectively). The prevalence may even be higher, as some individuals were noted as having possible Noonan‐like features (Tables S20 and S21), especially as Noonan‐like features are more difficult to discern in adulthood (Allanson, Hall, Hughes, Preus, & Witt, 1985). Importantly, p.Arg1276 and p.Lys1423 cohorts had a high prevalence of cardiac/cardiovascular abnormalities (23.9%, 22/92 and 25%, 19/76, respectively; Tables S22 and S23), including PS (12%, 11/92 and 14.5%, 11/76, respectively). Short stature and macrocephaly were present in 17.5% (14/80) and 31.6% (24/76) of p.Arg1276‐positive cases and in 41.2% (21/51) and 29.4% (15/51) of p.Lys1423‐positive cases, respectively. The prevalence of cognitive impairment and/or learning disabilities was estimated at 43.8% (46/105) and 41.4% (36/87) in p.Arg1276 and p.Lys1423 cohorts, respectively.

3.4. Comparison of clinical features of the studied cohorts with “classic” NF1 population, individuals carrying nonsense variants and cohorts of individuals with previously reported NF1 genotype–phenotype correlations

Detailed results of comparisons between phenotypes in the studied groups and the NF1 codons 844‐848‐, 1809‐, and p.Met992del‐positive cohorts, “classic” NF1‐affected cohorts, and the cohort of individuals with one of the 18 most recurrent nonsense variants identified in the UAB database are presented in Tables 1, 2, 3, Table S18, and Tables S24–S27.

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical features of the cohort of individuals heterozygous for pathogenic NF1 missense variants affecting p.Met1149 with the cohorts of individuals with pathogenic NF1 missense variants affecting codons 1809 and 844‐848, the NF1 p.Met992del as well as with large‐scale previously reported cohorts of individuals with “classic” NF1

| NF1 feature | N (%) | p Value (two‐tailed Fisher's exact test) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p.Met1149 | p.Met992del a | p.Arg1809 b | aa 844‐848 c | Previously reported NF1 cohorts d | p.Met1149 versus p.Met992del | p.Met1149 versus p.Arg1809 | p.Met1149 versus aa 844‐848 | p.Met1149 versus “classic” NF1 | |

| >5 CALMs | 62/69 (89.9) | 165/182 (90.7) | 157/169 (92.9) | 130/157 (82.8) | 1,537/1,728 (89) | ||||

| Skinfold freckling | 40/65 (61.5) | 105/171 (61.4) | 95/161 (59) | 104/144 (72.2) | 1,403/1,667 (84.2) | <0.0001** ↘ | |||

| Lisch nodules | 3/44 (6.8) | 16/139 (11.5) | 12/120 (10) | 42/98 (42.9) | 729/1,237 (58.9) | <0.0001** ↘ | <0.0001** ↘ | ||

| Major external plexiform neurofibromas e | 0/42 (0) | 0/125 (0) | 0/105 (0) | 36/92 (39.1) | 120/648 (18.5) | <0.0001 ** ↘ | 0.0005 ** ↘ | ||

| Cutaneous neurofibromas f | 0–3/24 (0–12.5) g | 0–1/57 (0–1.8) g | 0/57 (0) | 47/69 (68.1) | 656/723 (90.7) | <0.0001** ↘ | <0.0001** ↘ | ||

| Subcutaneous neurofibromas f | 0–3/22 (0–13.6) g | 0–3/36 (0–8.3) g | 0–5/57 (0–8.8) g | 33/65 (50.8) | 297/515 (57.7) | <0.0001** ↘ | <0.0001** ↘ | ||

| Symptomatic spinal neurofibromas | 0/59 (0) | 1/165 (0.6) | 0/76 (0) | 13/127 (10.2) | 36/2,058 (1.8) | ||||

| Symptomatic OPGs h | 0/58 (0) | 0/170 (0) | 0/139 (0) | 12/136 (8.8) | 64/1,650 (3.9) | ||||

| Asymptomatic OPGs i | 0/23 (0) | 1/41 (2.4) | 0/38 (0) | 18/63 (28.6) | 70/519 (13.5) | 0.0023* ↘ | |||

| Other malignant neoplasms j | 0/57 (0) | 1/126 (0.8) k | 2/155 (1.3) l | 13/139 (9.4) | 18/523 (3.4) | ||||

| Skeletal abnormalities | 15/61 (24.6) | 30/172 (17.4) | 21/126 (16.7) | 48/144 (33.3) | 144/948 (15.2) | ||||

| Scoliosis f | 2/20 (10) | 7/57 (12.3) | 6/48 (12.5) | 20/64 (31.3) | 51/236 (21.6) | ||||

| Cognitive impairment and/or learning disabilities | 31/66 (47) | 58/176 (33) | 80/159 (50.3) | 56/138 (40.6) | 190/424 (44.8) | ||||

| Noonan‐like phenotype m | 18/62 (29) | 19/166 (11.5) | 46/148 (31.1) | 10/134 (7.5) | 57/1,683 (3.4) | 0.0023* ↗ | 0.0001** ↗ | <0.0001** ↗ | |

| Short stature n | 5/33 (15.2) | 16/118 (13.6) | 32/111 (28.8) | 15/91 (16.5) | 109/684 (15.9) | ||||

| Macrocephaly | 19/45 (42.2) | 30/132 (22.7) | 31/107 (29) | 36/98 (36.7) | 239/704 (33.9) | ||||

| Pulmonic stenosis | 2/52 (3.9) | 8/160 (5) | 14/132 (10.6) | 2/113 (1.8) | 25/2,322 (1.1) | ||||

| Cardiovascular abnormalities | 5/52 (9.6) | 16/160 (10) | 21/118 (17.8) | 16/113 (14.2) | 54/2,322 (2.3) | ||||

Note: Statistically significant p values with FDR of 0.05 (indicated by*) and 0.01 (indicated by**) after correction for multiple testing using Benjamini–Hochberg procedure (see details in Table S24). After applying the Benjamini–Hochberg correction, p ≤ .0023 and p ≤ .0005 remained statistically significant at FDR of 0.05 and 0.01, respectively. The black arrows indicate the statistically significant differences of the NF1 clinical features prevalence between the p.Met1149 group and the cohort(s) used for the comparison, with the up and down arrows representing an increase and a decrease of the prevalence in the p.Met1149 group, respectively.

Abbreviations: CALM, café‐au‐lait macule; FDR, false discovery rate; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; OPG, optic pathway glioma.

Based on data from Pinna et al. (2015), Rojnueangnit et al. (2015), Ekvall et al. (2014), Nyström et al. (2009) and Santoro et al. (2015).

Based on data from Koczkowska et al. (2018).

Previous NF1 cohorts used for the comparison: Huson, Harper, and Compston (1988), Huson, Compston, Clark et al. (1989), Huson, Compston, and Harper (1989), Listernick, Charrow, Greenwald, and Mets (1994), Friedman and Birch (1997), Cnossen et al. (1998), McGaughran et al. (1999), Thakkar, Feigen, and Mautner (1999), Lin et al. (2000), Blazo et al. (2004), Khosrotehrani et al. (2005), Plotkin et al. (2012), and/or Blanchard et al. (2016).

In individuals ≥9 years old.

In individuals ≥19 years old.

Individuals with few (2–6) cutaneous and/or subcutaneous “neurofibromas,” none were biopsied and therefore none have been histologically confirmed.

The absence of symptomatic OPGs was determined by ophthalmological examination and/or by MRI.

Including only individuals without signs of symptomatic OPGs who underwent MRI examination.

Only malignant neoplasms, not including OPGs and neurofibromas, have been taken into account.

A single case of neuroblastoma (n = 1) was found in the NF1 p.Met992del cohort, no follow‐up information on this individual was available.

Breast cancer (n = 1) and Ewing sarcoma (n = 1) were found in the NF1 p.Arg1809 cohort, no follow‐up information on these individuals was available.

An individual was classified as having a Noonan‐like phenotype when at least two of the following features were present: short stature, low set ears, hypertelorism, midface hypoplasia, webbed neck, pectus abnormality, and/or pulmonic stenosis.

As no specific growth curves are available for the Hispanic and Asian populations, Hispanic and Asian individuals were excluded as having short or normal stature.

Table 2.

Comparison of clinical features of the cohort of individuals heterozygous for pathogenic NF1 missense variants affecting p.Arg1276 with the cohorts of individuals with pathogenic NF1 missense variants affecting codons 1809 and 844‐848, the NF1 p.Met992del as well as with large‐scale previously reported cohorts of individuals with “classic” NF1

| NF1 feature | N (%) | p Value (two‐tailed Fisher's exact test) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p.Arg1276 | p.Met992del a | p.Arg1809 b | aa 844‐848 c | Previously reported NF1 cohorts d | p.Arg1276 versus p.Met992del | p.Arg1276 versus p.Arg1809 | p.Arg1276 versus aa 844‐848 | p.Arg1276 versus “classic” NF1 | |

| >5 CALMs | 111/119 (93.3) | 165/182 (90.7) | 157/169 (92.9) | 130/157 (82.8) | 1,537/1,728 (89) | ||||

| Skinfold freckling | 74/112 (66.1) | 105/171 (61.4) | 95/161 (59) | 104/144 (72.2) | 1,403/1,667 (84.2) | <0.0001** ↘ | |||

| Lisch nodules | 19/70 (24.1) | 16/139 (11.5) | 12/120 (10) | 42/98 (42.9) | 729/1,237 (58.9) | 0.0059* ↗ | 0.0038* ↗ | <0.0001** ↘ | |

| Major external plexiform neurofibromas e | 5/64 (7.8) | 0/125 (0) | 0/105 (0) | 36/92 (39.1) | 120/648 (18.5) | 0.0040* ↗ | 0.0070* ↗ | <0.0001** ↘ | |

| Cutaneous neurofibromas f | 14/40 (35) | 0–1/57 (0–1.8) g | 0/57 (0) | 47/69 (68.1) | 656/723 (90.7) | <0.0001** ↗ | <0.0001** ↗ | 0.0012* ↘ | <0.0001** ↘ |

| Subcutaneous neurofibromas f | 21/37 (56.8) | 0–3/36 (0–8.3) g | 0–5/57 (0–8.8) g | 33/65 (50.8) | 297/515 (57.7) | <0.0001** ↗ | <0.0001** ↗ | ||

| Symptomatic spinal neurofibromas | 18/97 (18.6) h | 1/165 (0.6) | 0/76 (0) | 13/127 (10.2) | 36/2,058 (1.8) | <0.0001** ↗ | <0.0001** ↗ | <0.0001** ↗ | |

| Symptomatic OPGs i | 0/97 (0) | 0/170 (0) | 0/139 (0) | 12/136 (8.8) | 64/1,650 (3.9) | 0.0016* ↘ | |||

| Asymptomatic OPGs j | 1/48 (2.1) | 1/41 (2.4) | 0/38 (0) | 18/63 (28.6) | 70/519 (13.5) | 0.0002** ↘ | |||

| Other malignant neoplasms k | 4/94 (4.3) l | 1/126 (0.8) m | 2/155 (1.3) n | 13/139 (9.4) | 18/523 (3.4) | ||||

| Skeletal abnormalities | 32/100 (32) | 30/172 (17.4) | 21/126 (16.7) | 48/144 (33.3) | 144/948 (15.2) | 0.0070* ↗ | 0.0076* ↗ | 0.0001** ↗ | |

| Scoliosis f | 8/35 (22.9) | 7/57 (12.3) | 6/48 (12.5) | 20/64 (31.3) | 51/236 (21.6) | ||||

| Cognitive impairment and/or learning disabilities | 46/105 (43.8) | 58/176 (33) | 80/159 (50.3) | 56/138 (40.6) | 190/424 (44.8) | ||||

| Noonan‐like phenotype o | 22/106 (20.8) | 19/166 (11.5) | 46/148 (31.1) | 10/134 (7.5) | 57/1,683 (3.4) | 0.0037* ↗ | <0.0001** ↗ | ||

| Short stature p | 14/80 (17.5) | 16/118 (13.6) | 32/111 (28.8) | 15/91 (16.5) | 109/684 (15.9) | ||||

| Macrocephaly | 24/76 (31.6) | 30/132 (22.7) | 31/107 (29) | 36/98 (36.7) | 239/704 (33.9) | ||||

| Pulmonic stenosis | 11/92 (12) | 8/160 (5) | 14/132 (10.6) | 2/113 (1.8) | 25/2,322 (1.1) | 0.0034* ↗ | <0.0001** ↗ | ||

| Cardiovascular abnormalities | 22/92 (23.9) | 16/160 (10) | 21/118 (17.8) | 16/113 (14.2) | 54/2,322 (2.3) | 0.0055** ↗ | <0.0001** ↗ | ||

Note: Statistically significant p values with FDR of 0.05 (indicated by *) and 0.01 (indicated by **) after correction for multiple testing using Benjamini–Hochberg procedure (see details in Table S25). After applying the Benjamini–Hochberg correction, p ≤ .0076 and p ≤ .0002 remained statistically significant at FDR of 0.05 and 0.01, respectively. The black arrows indicate the statistically significant differences of the NF1 clinical features prevalence between the p.Arg1276 group and the cohort(s) used for the comparison, with the up and down arrows representing an increase and a decrease of the prevalence in the p.Arg1276 group, respectively.

Abbreviations: CALM, café‐au‐lait macule; FDR, false discovery rate; MPNST, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; OPG, optic pathway glioma.

Based on data from Pinna et al. (2015), Rojnueangnit et al. (2015), Ekvall et al. (2014), Nyström et al. (2009), and Santoro et al. (2015).

Based on data from Koczkowska et al. (2018).

Previous NF1 cohorts used for the comparison: Huson et al. (1988), Huson, Compston, Clark et al. (1989), Huson, Compston, and Harper (1989), Listernick et al. (1994), Friedman and Birch (1997), Cnossen et al. (1998), McGaughran et al. (1999), Thakkar et al. (1999), Lin et al. (2000), Blazo et al. (2004), Khosrotehrani et al. (2005), Plotkin et al. (2012), and/or Blanchard et al. (2016).

In individuals ≥9 years old.

In individuals ≥19 years old.

Individuals with few (2–6) cutaneous and/or subcutaneous “neurofibromas,” none were biopsied and therefore none have been histologically confirmed.

The overall prevalence of symptomatic spinal neurofibromas in all individuals was 18.6% (18/97) but in adults 47.2% (17/36 ≥ 19 years old).

The absence of symptomatic OPGs was determined by ophthalmological examination and/or by MRI.

Including only individuals without signs of symptomatic OPGs who underwent MRI examination.

Only malignant neoplasms, not including OPGs and neurofibromas, have been taken into account.

Astrocytoma (n = 2), colon cancer (n = 1) and MPNST (n = 1) were found in the NF1 p.Arg1276 cohort.

A single case of neuroblastoma (n = 1) was found in the NF1 p.Met992del cohort, no follow‐up information on this individual was available.

Breast cancer (n = 1) and Ewing sarcoma (n = 1) were found in the NF1 p.Arg1809 cohort, no follow‐up information on these individuals was available.

An individual was classified as having a Noonan‐like phenotype when at least two of the following features were present: short stature, low set ears, hypertelorism, midface hypoplasia, webbed neck, pectus abnormality, and/or pulmonic stenosis.

As no specific growth curves are available for the Hispanic and Asian populations, Hispanic and Asian individuals were excluded as having short or normal stature.

Table 3.

Comparison of clinical features of the cohort of individuals heterozygous for pathogenic NF1 missense variants affecting p.Lys1423 with the cohorts of individuals with pathogenic NF1 missense variants affecting codons 1809 and 844‐848, the NF1 p.Met992del as well as with large‐scale previously reported cohorts of individuals with “classic” NF1

| NF1 feature | N (%) | p Value (two‐tailed Fisher's exact test) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p.Lys1423 | p.Met992del a | p.Arg1809 b | aa 844‐848 c | Previously reported NF1 cohorts d | p.Lys1423 versus p.Met992del | p.Lys1423 versus p.Arg1809 | p.Lys1423 versus aa 844‐848 | p.Lys1423 versus “classic” NF1 | |

| >5 CALMs | 86/91 (94.5) | 165/182 (90.7) | 157/169 (92.9) | 130/157 (82.8) | 1,537/1,728 (89) | ||||

| Skinfold freckling | 65/85 (76.5) | 105/171 (61.4) | 95/161 (59) | 104/144 (72.2) | 1,403/1,667 (84.2) | 0.0074* ↗ | |||

| Lisch nodules | 31/59 (52.5) | 16/139 (11.5) | 12/120 (10) | 42/98 (42.9) | 729/1,237 (58.9) | <0.0001** ↗ | <0.0001** ↗ | ||

| Major external plexiform neurofibromas e | 14/48 (29.2) | 0/125 (0) | 0/105 (0) | 36/92 (39.1) | 120/648 (18.5) | <0.0001** ↗ | <0.0001** ↗ | ||

| Cutaneous neurofibromas f | 23/28 (82.1) | 0–1/57 (0–1.8) g | 0/57 (0) | 47/69 (68.1) | 656/723 (90.7) | <0.0001** ↗ | <0.0001** ↗ | ||

| Subcutaneous neurofibromas f | 13/23 (56.5) | 0–3/36 (0–8.3) g | 0–5/57 (0–8.8) g | 33/65 (50.8) | 297/515 (57.7) | <0.0001** ↗ | <0.0001** ↗ | ||

| Symptomatic spinal neurofibromas | 3/65 (4.6) | 1/165 (0.6) | 0/76 (0) | 13/127 (10.2) | 36/2,058 (1.8) | ||||

| Symptomatic OPGs h | 1/74 (1.4) | 0/170 (0) | 0/139 (0) | 12/136 (8.8) | 64/1,650 (3.9) | ||||

| Asymptomatic OPGs i | 6/40 (15) | 1/41 (2.4) | 0/38 (0) | 18/63 (28.6) | 70/519 (13.5) | ||||

| Other malignant neoplasms j | 7/77 (9.1) k | 1/126 (0.8) l | 2/155 (1.3) m | 13/139 (9.4) | 18/523 (3.4) | 0.0052* ↗ | 0.0070* ↗ | ||

| Skeletal abnormalities | 34/83 (41) | 30/172 (17.4) | 21/126 (16.7) | 48/144 (33.3) | 144/948 (15.2) | <0.0001** ↗ | 0.0002** ↗ | <0.0001** ↗ | |

| Scoliosis f | 10/27 (37) | 7/57 (12.3) | 6/48 (12.5) | 20/64 (31.3) | 51/236 (21.6) | ||||

| Cognitive impairment and/or learning disabilities | 36/87 (41.4) | 58/176 (33) | 80/159 (50.3) | 56/138 (40.6) | 190/424 (44.8) | ||||

| Noonan‐like phenotype n | 24/83 (28.9) | 19/166 (11.5) | 46/148 (31.1) | 10/134 (7.5) | 57/1,683 (3.4) | 0.0011** ↗ | <0.0001** ↗ | <0.0001** ↗ | |

| Short stature o | 21/51 (41.2) | 16/118 (13.6) | 32/111 (28.8) | 15/91 (16.5) | 109/684 (15.9) | 0.0002** ↗ | 0.0022* ↗ | <0.0001** ↗ | |

| Macrocephaly | 15/51 (29.4) | 30/132 (22.7) | 31/107 (29) | 36/98 (36.7) | 239/704 (33.9) | ||||

| Pulmonic stenosis | 11/76 (14.5) | 8/160 (5) | 14/132 (10.6) | 2/113 (1.8) | 25/2,322 (1.1) | 0.0010** ↗ | <0.0001** ↗ | ||

| Cardiovascular abnormalities | 19/76 (25) | 16/160 (10) | 21/118 (17.8) | 16/113 (14.2) | 54/2,322 (2.3) | 0.0053** ↗ | <0.0001** ↗ | ||

Note: Statistically significant p values with FDR of 0.05 (indicated by *) and 0.01 (indicated by **) after correction for multiple testing using Benjamini–Hochberg procedure (see details in Table S26). After applying the Benjamini–Hochberg correction, p ≤ .0074 and p ≤ .0011 remained statistically significant at FDR of 0.05 and 0.01, respectively. The black arrows indicate the statistically significant differences of the NF1 clinical features prevalence between the p.Lys1423 group and the cohort(s) used for the comparison, with the up and down arrows representing an increase and a decrease of the prevalence in the p.Lys1423 group, respectively.

Abbreviations: CALM, café‐au‐lait macule; FDR, false discovery rate; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; OPG, optic pathway glioma.

Based on data from Pinna et al. (2015), Rojnueangnit et al. (2015), Ekvall et al. (2014), Nyström et al. (2009), and Santoro et al. (2015).

Based on data from Koczkowska et al. (2018).

Previous NF1 cohorts used for the comparison: Huson et al. (1988), Huson, Compston, Clark et al. (1989), Huson, Compston, and Harper (1989), Listernick et al. (1994), Friedman and Birch (1997), Cnossen et al. (1998), McGaughran et al. (1999), Thakkar et al. (1999), Lin et al. (2000), Blazo et al. (2004), Khosrotehrani et al. (2005), Plotkin et al. (2012), and/or Blanchard et al. (2016).

In individuals ≥9 years old.

In individuals ≥19 years old.

Individuals with few (2–6) cutaneous and/or subcutaneous “neurofibromas,” none were biopsied and therefore none have been histologically confirmed.

The absence of symptomatic OPGs was determined by ophthalmological examination and/or by MRI.

Including only individuals without signs of symptomatic OPGs who underwent MRI examination.

Only malignant neoplasms, not including OPGs and neurofibromas, have been taken into account.

Astrocytoma (n = 1), rhabdomyosarcoma (n = 1), hypothalamic glioma (n = 2), brainstem glioma (n = 1), colon adenocarcinoma (n = 1), and cerebellar glioblastoma (n = 1) were found in the NF1 p.Lys1423 cohort.

A single case of neuroblastoma (n = 1) was found in the NF1 p.Met992del cohort, no follow‐up information on this individual was available.

Breast cancer (n = 1) and Ewing sarcoma (n = 1) were found in the NF1 p.Arg1809 cohort, no follow‐up information on these individuals was available.

An individual was classified as having a Noonan‐like phenotype when at least two of the following features were present: short stature, low set ears, hypertelorism, midface hypoplasia, webbed neck, pectus abnormality, and/or pulmonic stenosis.

As no specific growth curves are available for the Hispanic and Asian populations, Hispanic and Asian individuals were excluded as having short or normal stature.

All missense variants studied in the current research were associated with a high prevalence of Noonan‐like phenotypes compared with the general NF1 population and/or the cohort carrying an NF1 nonsense variant (all p < .0001, significant at FDR of 0.01 after B‐H correction). Moreover, p.Arg1276‐ and p.Lys1423‐positive individuals had a very significantly increased prevalence of cardiac/cardiovascular abnormalities, including PS, compared with the “classic” NF1 and nonsense variant cohorts (all p < .0001, significant at FDR of 0.01 after B‐H correction).

Phenotype in p.Met1149‐positive cases were similar to that of individuals with the p.Met992del and p.Arg1809 pathogenic variants, including paucity of superficial plexiform and histopathologically confirmed cutaneous and/or subcutaneous neurofibromas. No symptomatic spinal neurofibromas, symptomatic OPGs, or malignant neoplasms were found in this cohort (Table 1).

Compared with the general NF1 population, p.Arg1276‐positive individuals showed a high prevalence of symptomatic spinal neurofibromas (p < .0001, significant at FDR of 0.01 after B‐H correction) and a lower prevalence of cutaneous neurofibromas (p < .0001, significant at FDR of 0.01 after B‐H correction).

Pathogenic NF1 missense variants at p.Lys1423 may predispose to major external plexiform neurofibromas compared with “classic” NF1‐affected cohorts (29.2% vs.18.5%; p = .0863, but not significant).

Both p.Arg1276 and p.Lys1423 cohorts had a higher incidence of skeletal abnormalities (Table S28) compared with the general NF1 population (both p ≤ .0001, significant at FDR of 0.01 after B‐H correction).

There were no statistical differences in the prevalence of NF1 clinical features between cohorts of individuals heterozygous for p.Met1149, p.Arg1276, or p.Lys1423 referred to UAB and to the collaborating European institutions (Tables S29 and S30).

4. DISCUSSION

NF1 and Noonan syndrome (NS; MIM# 163950) represent RASopathies, a group of phenotypically related conditions, caused by pathogenic variants in genes involved in the RAS/mitogen‐activated protein kinase signaling transduction pathway. Due to some overlapping phenotypic features, a clinical diagnosis can be complicated. “Classic” NF1 cases presenting with Noonan‐like features were classified as having neurofibromatosis‐Noonan syndrome (NFNS; MIM# 601321), first described 30 years ago (Allanson, Hall, & Van Allen, 1985; Opitz & Weaver, 1985). Although few cases have been reported to carry both a pathogenic NF1 and PTPN11 (MIM# 176876) variant (Bertola et al., 2005; Nyström et al., 2009; Thiel et al., 2009), as a rule, NF1 is the genetic cause underlying NFNS. De Luca et al. (2005) identified pathogenic variants spread across the NF1 gene, including nonsense, missense, out‐of‐frame and small in‐frame deletions, and one multiexon deletion in 16/17 unrelated NFNS individuals. Among four individuals with NFNS and PS, 2/4 carried an in‐frame single amino acid deletion and 1/4 a pathogenic missense variant with 2/3 located in the GTPase‐activating protein‐related domain (GAP‐GRD). Ben‐Shachar et al. (2013) reported a higher prevalence of PS in NFNS individuals compared with the general NF1 population (9/35, 26% vs. 25/2322, 1.1%; p < .001), with NFNS cases carrying a nontruncating pathogenic variant having the highest risk (p < .001). However, this study did not provide more specific information related to location or type of nontruncating pathogenic variants and was not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

So far, only two specific NF1 pathogenic variants have been associated with a statistically significant increased prevalence of Noonan‐like features compared with “classic” NF1‐affected cohorts, i.e., p.Arg1809 and p.Met992del, both located outside the GRD (Koczkowska et al., 2019; Pinna et al., 2015; Rojnueangnit et al., 2015; Upadhyaya et al., 2007). Here, we report that NF1 pathogenic missense variants at p.Met1149, p.Arg1276, and p.Lys1423 also are associated with this distinct phenotype (all p < .0001, significant at FDR of 0.01 after B‐H correction), with no pathogenic variants in other NS genes detected (Tables S6, S8, S10, S12, S20, and S21). A high prevalence of PS was associated with p.Arg1276, p.Lys1423 and p.Arg1809 compared to the general NF1 population as well as the UAB NF1 nonsense variant cohort (all P < 0.0001, significant at FDR of 0.01 after B‐H correction, Tables 2, 3 and Table S18). These observations provide evidence that although PS overall is more frequently observed in individuals carrying one of the nontruncating pathogenic variants in the current and previous studies (48/625, 7.7%), the prevalence of PS and other cardiac/cardiovascular abnormalities is highest in the p.Arg1276‐ and p.Lys1423‐ positive individuals, both located in the GRD (at least 10‐fold higher than in the “classic” NF1 population; Table 4 and Tables S31 and S32), whereas is not significantly increased in individuals carrying pathogenic variants affecting codons 844‐848 and 1149. As cardiovascular abnormalities may be congenital or become symptomatic at a young age and are associated with morbidity and mortality (Friedman et al., 2002; Lin et al., 2000), all individuals carrying one of the aforementioned pathogenic NF1 missense variants should receive a detailed cardiac examination.

Table 4.

Risk ratio calculations with 95% CI for the comparison of NF1 clinical features in the studied p.Met1149‐, p.Arg1276‐, and p.Lys1423‐positive cohorts with the “classic” NF1 population

| NF1 feature | Risk ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| p.Met1149 versus “classic” NF1 | p.Arg1276 versus “classic” NF1 | p.Lys1423 versus “classic” NF1 | |

| Skinfold freckling | 0.73 (0.60–0.89) | 0.78 (0.69–0.90) | |

| Lisch nodules | 0.12 (0.04–0.35) | 0.46 (0.31–0.68) | |

| Cutaneous neurofibromas | 0.14 (0.05–0.40) | 0.38 (0.25–0.59) | |

| Subcutaneous neurofibromas | 0.24 (0.08–0.68) | ||

| Symptomatic spinal neurofibromas | 10.61 (6.26–17.98) | ||

| Skeletal abnormalities | 2.11 (1.52–2.91) | 2.70 (2.00–3.64) | |

| Noonan‐like phenotype | 8.57 (5.38–13.65) | 6.13 (3.90–9.62) | 8.54 (5.59–13.03) |

| Short stature | 2.58 (1.78–3.74) | ||

| Pulmonic stenosis | 11.10 (5.64–21.87) | 13.44 (6.87–26.30) | |

| Cardiovascular abnormalities | 10.28 (6.56–16.12) | 10.75 (6.72–17.20) | |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Watson syndrome (WS; MIM# 193520) was described in 1967 and is characterized by CALMs, PS, and intellectual disability, and is allelic to NF1 (Ben‐Shachar et al., 2013; Watson, 1967). Among 24 cases with PS found in this report, one 12‐year‐old individual (UAB‐R1256) presented solely with greater than five CALMs, PS, developmental delay, severe scoliosis, and short stature. Additionally, two children less than 4 years old (UAB‐R37401FN.202 and UAB‐R8917) had greater than five CALMs, PS, abnormal development with speech delay, and Noonan‐like facial features as the only features. NF1 c.3827G>A (p.Arg1276Gln), identified in the largest WS family from the original study (Ben‐Shachar et al., 2013; Watson, 1967) was also found in UAB‐R1256. Although 40% of the p.Arg1276‐positive individuals ≥9 years old (29/73) had a severe phenotype with cardiac/cardiovascular abnormalities and/or spinal neurofibromas, 26% of cases ≥9 years old (19/73) presented with only pigmentary manifestations and a variable amount of learning disabilities (Table S6). Therefore, further studies aimed at identifying potential modifying genes, unlinked to the NF1 locus, in these individuals should be considered.

Familial spinal neurofibromatosis (FSNF; MIM# 162210) is another rare subtype of NF1, characterized by the presence of multiple histopathologically confirmed neurofibromas along spinal nerve roots with few, if any, cutaneous neurofibromas, but often multiple firm subcutaneous tumors and CALMs (Korf, 2015; Pulst, Riccardi, Fain, & Korenberg, 1991; Ruggieri et al., 2015). Although pathogenic NF1 missense and splicing variants are more commonly found in these individuals (Kluwe, Tatagiba, Fünsterer, & Mautner, 2003; Messiaen, Riccardi, & Peltonen, 2003; Upadhyaya et al., 2009), no specific recurrent variants associated with symptomatic spinal neurofibromas were identified, except recently for pathogenic missense variants affecting p.Gly848 (Koczkowska et al., 2018). In the current study, we identified p.Arg1276Gln being the second specific NF1 variant associated with a high prevalence of symptomatic spinal neurofibromas (11‐fold higher than in the general NF1 population; Table 4), found in 55.6% of individuals greater than 19 years (15/27; Table S10), including 4/15 with so‐called spinal form of NF1 (Table S14 and Figure S5). An additional 4/6 p.Arg1276Gln‐positive adults who underwent routine MRI screening had asymptomatic spinal tumors, and such individuals may possibly be eligible for treatment with MEK inhibitors. Similar to p.Gly848‐positive individuals (Koczkowska et al., 2018), fewer individuals ≥19 years developed cutaneous neurofibromas compared with “classic” cohorts (p < .0001, significant at FDR of 0.01 after B‐H correction; Table 2). Cutaneous neurofibromas were observed in only one‐third of p.Arg1276Gln‐positive cases with spinal tumors (7/19), ranging in number from 2 to 99, while the majority of NF1‐affected individuals ≥30 years old with “classic” NF1 exhibit greater than 100 neurofibromas (Mautner et al., 2008). Only EUR‐R32, carrying a different pathogenic variant, p.Arg1276Pro, presented with greater than 100 cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions at age of 60 years (Table S14). Among 22 individuals with spinal tumors, 16 cases had normal development in line with previous findings (Korf, 2015).

NF1 p.Arg1276 and p.Lys1423 are highly conserved residues lying in a shallow pocket in the central catalytic domain forming the RAS‐binding region with the p.Arg1276 residue also called the arginine “finger,” being the most essential catalytic element for RasGAP activity (Scheffzek, Ahmadian, & Wiesmüller, 1998). Functional studies have shown that pathogenic variants affecting these residues result in a dramatic reduction of GAP activity (Poullet, Lin, Esson, & Tamanoi, 1994; Scheffzek et al., 1998; Ahmadian, Kiel, Stege, & Scheffzek, 2003). Moreover, pathogenic missense variants at residue p.Lys1423 affects the stability of the neurofibromin/RAS complex by disrupting an intramolecular salt‐bridge of the GRD (Ahmadian et al., 2003).

In this study, we report an additional NF1 variant, p.Met1149Val, associated specifically with a mild form of NF1 without externally visible plexiform or symptomatic spinal neurofibromas, symptomatic OPGs or malignant neoplasms similar to the phenotypes associated with variants at p.Arg1809 and p.Met992del (Koczkowska et al., 2019; Pinna et al., 2015; Rojnueangnit et al., 2015; Upadhyaya et al., 2007). As only six probands were identified so far with either the p.Met1149Ile or p.Met1149Thr (Table S7), even larger datasets, as well as follow‐up of individuals enrolled in the current study, are required to further refine a mild phenotype associated with the other substitutions at p.Met1149. Therefore, we have now shown that approximately 2.5% of all unrelated NF1 pathogenic variant‐positive probands of the UAB cohort develop a mild phenotype associated with nontruncating recurrent variants at one of three residues, p.Met992, p.Arg1809, and p.Met1149. Identification of this additional genotype–phenotype correlation will benefit the genetic counseling of these individuals and allow their stratification as they may not require stringent follow‐up care. Moreover, as only 75% of p.Met1149‐positive individuals fulfilled the NIH diagnostic criteria when family history was excluded as a criterion (Table S9), molecular analysis significantly facilitates the NF1 diagnostic process and distinguishes Legius syndrome (MIM# 611431) from the p.Met992del, p.Arg1809, and now p.Met1149 phenotypes with clinically overlapping features.

5. CONCLUSION

Although single case reports may suggest an association of p.Arg1276 with spinal neurofibromas (Korf, Henson, & Stemmer‐Rachamimov, 2005; Upadhyaya et al., 2009) or p.Lys1423 with Noonan‐like features (De Luca et al., 2005) (two unrelated individuals described with each phenotype), only large datasets of postpubertal individuals, carrying the same constitutional pathogenic variant and with the phenotype recorded in a standardized way allow the establishment of clinically relevant genotype–phenotype correlations. International multicenter studies involving close collaborations between NF1 clinicians and molecular geneticists are required to unfold such associations and to enhance correct variant interpretation. Our findings demonstrate genotype–phenotype correlations at the NF1 codons p.Met1149, p.Arg1276, and p.Lys1423. Although each of the reported NF1 variants associated with a specific clinical presentation (Kehrer‐Sawatzki et al., 2017; Koczkowska et al., 2018; Koczkowska et al., 2019; Pinna et al., 2015; Rojnueangnit et al., 2015; Upadhyaya et al., 2007) affects only a small percentage of NF1 individuals, together, including the current results, they affect counseling and management of approximately 10% of the NF1 population. As the number of NF1 genotype–phenotype correlations continues to accumulate, genotype‐driven personalized medicine will reach a turning point in NF1 by improving the disease surveillance and stratification of NF1‐affected individuals.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

Supporting information

Supporting information

Supporting information

Supporting information

Supporting information

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the individuals and their families for participating in this study.

Koczkowska M, Callens T, Chen Y, et al. Clinical spectrum of individuals with pathogenic NF1 missense variants affecting p.Met1149, p.Arg1276, and p.Lys1423: genotype–phenotype study in neurofibromatosis type 1. Human Mutation. 2020;41:299–315. 10.1002/humu.23929

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Ahmadian, M. R. , Kiel, C. , Stege, P. , & Scheffzek, K. (2003). Structural fingerprints of the Ras‐GTPase activating proteins neurofibromin and p120GAP. Journal of Molecular Biology, 329(4), 699–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allanson, J. E. , Hall, J. G. , Hughes, H. E. , Preus, M. , & Witt, R. D. (1985). Noonan syndrome: The changing phenotype. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 21(3), 507–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allanson, J. E. , Hall, J. G. , & Van Allen, M. I. (1985). Noonan phenotype associated with neurofibromatosis. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 21(3), 457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben‐Shachar, S. , Constantini, S. , Hallevi, H. , Sach, E. K. , Upadhyaya, M. , Evans, G. D. , & Huson, S. M. (2013). Increased rate of missense/in‐frame mutations in individuals with NF1‐related pulmonary stenosis: A novel genotype‐phenotype correlation. European Journal of Human Genetics, 21(5), 535–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertola, D. R. , Pereira, A. C. , Passetti, F. , de Oliveira, P. S. L. , Messiaen, L. , Gelb, B. D. , … Krieger, J. E. (2005). Neurofibromatosis‐Noonan syndrome: Molecular evidence of the concurrence of both disorders in a patient. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 136(3), 242–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard, G. , Lafforgue, M. P. , Lion‐François, L. , Kemlin, I. , Rodriguez, D. , Castelnau, P. , … Chaix, Y. (2016). Systematic MRI in NF1 children under six years of age for the diagnosis of optic pathway gliomas. Study and outcome of a French cohort. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology, 20(2), 275–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazo, M. A. , Lewis, R. A. , Chintagumpala, M. M. , Frazier, M. , McCluggage, C. , & Plon, S. E. (2004). Outcomes of systematic screening for optic pathway tumors in children with neurofibromatosis type 1. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 127A(3), 224–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cnossen, M. H. , de Goede‐Bolder, A. , van den Broek, K. M. , Waasdorp, C. M. E. , Oranje, A. P. , Stroink, H. , … Niermeijer, M. F. (1998). A prospective 10 year follow up study of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 78(5), 408–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca, A. , Bottillo, I. , Sarkozy, A. , Carta, C. , Neri, C. , Bellacchio, E. , … Dallapiccola, B. (2005). NF1 gene mutations represent the major molecular event underlying neurofibromatosis‐Noonan syndrome. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 77(6), 1092–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekvall, S. , Sjörs, K. , Jonzon, A. , Vihinen, M. , Annerén, G. , & Bondeson, M. L. (2014). Novel association of neurofibromatosis type 1‐causing mutations in families with neurofibromatosis‐Noonan syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics, Part A, 164A(3), 579–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, D. G. , Howard, E. , Giblin, C. , Clancy, T. , Spencer, H. , Huson, S. M. , & Lalloo, F. (2010). Birth incidence and prevalence of tumor‐prone syndromes: Estimates from a UK family genetic register service. American Journal of Medical Genetics, Part A, 152A(2), 327–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, J. M. (2014). Neurofibromatosis 1 In Pagon R. E., Adam M. P., & Ardinger H. H. (Eds.), GeneReviews®. Seattle, WA: University of Washington; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1109/. Accessed June 21, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, J. M. , Arbiser, J. , Epstein, J. A. , Gutmann, D. H. , Huot, S. J. , Lin, A. E. , … Korf, B. R. (2002). Cardiovascular disease in neurofibromatosis 1: Report of the NF1 cardiovascular task force. Genetics in Medicine, 4(3), 105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, J. M. , & Birch, P. H. (1997). Type 1 neurofibromatosis: A descriptive analysis of the disorder in 1,728 patients. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 70(2), 138–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huson, S. M. , Compston, D. A. , Clark, P. , & Harper, P. S. (1989). A genetic study of von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis in south east Wales. I. Prevalence, fitness, mutation rate, and effect of parental transmission on severity. Journal of Medical Genetics, 26(11), 704–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huson, S. M. , Compston, D. A. , & Harper, P. S. (1989). A genetic study of von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis in south east Wales. II. Guidelines for genetic counselling. J Med Genet, 26(11), 712–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huson, S. M. , Harper, P. S. , & Compston, D. A. S. (1988). Von recklinghausen neurofibromatosis: A clinical and population study in south‐east wales. Brain, 111(Pt 6), 1355–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehrer‐Sawatzki, H. , Mautner, V. F. , & Cooper, D. N. (2017). Emerging genotype‐phenotype relationships in patients with large NF1 deletions. Human Genetics, 136(4), 349–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosrotehrani, K. , Bastuji‐Garin, S. , Riccardi, V. M. , Birch, P. , Friedman, J. M. , & Wolkenstein, P. (2005). Subcutaneous neurofibromas are associated with mortality in neurofibromatosis 1: A cohort study of 703 patients. American Journal of Medical Genetics, Part A, 132A(1), 49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluwe, L. , Tatagiba, M. , Fünsterer, C. , & Mautner, V. F. (2003). NF1 mutations and clinical spectrum in patients with spinal neurofibromas. Journal of Medical Genetics, 40(5), 368–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koczkowska, M. , Callens, T. , Gomes, A. , Sharp, A. , Chen, Y. , Hicks, A. D. , … Messiaen, L. M. (2019). Expanding the clinical phenotype of individuals with a 3‐bp in‐frame deletion of the NF1 gene (c.2970_2972del): An update of genotype‐phenotype correlation. Genetics in Medicine, 21(4), 867–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koczkowska, M. , Chen, Y. , Callens, T. , Gomes, A. , Sharp, A. , Johnson, S. , … Messiaen, L. M. (2018). Genotype‐phenotype correlation in NF1: Evidence for a more severe phenotype associated with missense mutations affecting NF1 codons 844‐848. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 102(1), 69–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korf, B. R. (2015). Spinal neurofibromatosis and phenotypic heterogeneity in NF1. Clinical Genetics, 87(5), 399–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korf, B. R. , Henson, J. W. , & Stemmer‐Rachamimov, A. (2005). Case 13‐2005: A 48‐year‐old man with weakness of the limbs and multiple tumors of spinal nerves. New England Journal of Medicine, 352(17), 1800–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammert, M. , Friedman, J. M. , Kluwe, L. , & Mautner, V. F. (2005). Prevalence of neurofibromatosis 1 in German children at elementary school enrollment. Archives of Dermatology, 141(1), 71–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, A. E. , Birch, P. H. , Korf, B. R. , Tenconi, R. , Niimura, M. , Poyhonen, M. , … Friedman, J. M. (2000). Cardiovascular malformations and other cardiovascular abnormalities in neurofibromatosis 1. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 95(2), 108–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Listernick, R. , Charrow, J. , Greenwald, M. , & Mets, M. (1994). Natural history of optic pathway tumors in children with neurofibromatosis type 1: A longitudinal study. The Journal of Pediatrics, 125(1), 63–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mautner, V. F. , Asuagbor, F. A. , Dombi, E. , Fünsterer, C. , Kluwe, L. , Wenzel, R. , … Friedman, J. M. (2008). Assessment of benign tumor burden by whole‐body MRI in patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Neuro‐Oncology, 10(4), 593–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaughran, J. M. , Harris, D. I. , Donnai, D. , Teare, D. , MacLeod, R. , Westerbeek, R. , … Evans, D. G. (1999). A clinical study of type 1 neurofibromatosis in north west England. Journal of Medical Genetics, 36(3), 197–203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messiaen, L. (2003). Independent NF1 mutations in two large families with spinal neurofibromatosis. Journal of Medical Genetics, 40(2), 122–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messiaen, L. M. , Callens, T. , Mortier, G. , Beysen, D. , Vandenbroucke, I. , Van Roy, N. , … Paepe, A. D. (2000). Exhaustive mutation analysis of the NF1 gene allows identification of 95% of mutations and reveals a high frequency of unusual splicing defects. Human Mutation, 15(6), 541–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messiaen, L. M. , & Wimmer, K. (2012). Mutation analysis of the NF1 gene by cDNA‐based sequencing of the coding region In Cunha K. S. G., & Geller M. (Eds.), Advances in neurofibromatosis research (pp. 89–108). Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Nyström, A. M. , Ekvall, S. , Strömberg, B. , Holmström, G. , Thuresson, A. C. , Annerén, G. , & Bondeson, M. L. (2009). A severe form of Noonan syndrome and autosomal dominant café‐au‐lait spots—evidence for different genetic origins. Acta Paediatrica, 98(4), 693–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opitz, J. M. , & Weaver, D. D. (1985). The neurofibromatosis‐Noonan syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 21(3), 477–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna, V. , Lanari, V. , Daniele, P. , Consoli, F. , Agolini, E. , Margiotti, K. , … De Luca, A. (2015). p.Arg1809Cys substitution in neurofibromin is associated with a distinctive NF1 phenotype without neurofibromas. European Journal of Human Genetics, 23(8), 1068–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotkin, S. R. , Bredella, M. A. , Cai, W. , Kassarjian, A. , Harris, G. J. , Esparza, S. , … Mautner, V. F. (2012). Quantitative assessment of whole‐body tumor burden in adult patients with neurofibromatosis. PLoS One, 7(4), e35711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poullet, P. , Lin, B. , Esson, K. , & Tamanoi, F. (1994). Functional significance of lysine 1423 of neurofibromin and characterization of a second site suppressor which rescues mutations at this residue and suppresses RAS2Val‐19‐activated phenotypes. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 14(1), 815–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulst, S. M. , Riccardi, V. M. , Fain, P. , & Korenberg, J. R. (1991). Familial spinal neurofibromatosis: Clinical and DNA linkage analysis. Neurology, 41(12), 1923–1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards, S. , Aziz, N. , Bale, S. , Bick, D. , Das, S. , Gastier‐Foster, J. , … Rehm, H. L. (2015). Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genetics in Medicine, 17(5), 405–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojnueangnit, K. , Xie, J. , Gomes, A. , Sharp, A. , Callens, T. , Chen, Y. , … Messiaen, L. (2015). High incidence of Noonan syndrome features including short stature and pulmonic stenosis in patients carrying NF1 missense mutations affecting p.Arg1809: Genotype‐phenotype correlation. Human Mutation, 36(11), 1052–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggieri, M. , Polizzi, A. , Spalice, A. , Salpietro, V. , Caltabiano, R. , D'Orazi, V. , … Nicita, F. (2015). The natural history of spinal neurofibromatosis: A critical review of clinical and genetic features. Clinical Genetics, 87(5), 401–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro, C. , Maietta, A. , Giugliano, T. , Melis, D. , Perrotta, S. , Nigro, V. , & Piluso, G. (2015). Arg1809 substitution in neurofibromin: Further evidence of a genotype‐phenotype correlation in neurofibromatosis type 1. European Journal of Human Genetics, 23(11), 1460–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffzek, K. (1998). Structural analysis of the GAP‐related domain from neurofibromin and its implications. EMBO Journal, 17(15), 4313–4327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakkar, S. D. , Feigen, U. , & Mautner, V. F. (1999). Spinal tumours in neurofibromatosis type 1: An MRI study of frequency, multiplicity, and variety. Neuroradiology, 41(9), 625–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel, C. , Wilken, M. , Zenker, M. , Sticht, H. , Fahsold, R. , Gusek‐Schneider, G. C. , & Rauch, A. (2009). Independent NF1 and PTPN11 mutations in a family with neurofibromatosis‐Noonan syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 149(6), 1263–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thissen, D. , Steinberg, L. , & Kuang, D. (2002). Quick and easy implementation of the Benjamini‐Hochberg procedure for controlling the false positive rate in multiple comparisons. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 27(1), 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyaya, M. , Huson, S. M. , Davies, M. , Thomas, N. , Chuzhanova, N. , Giovannini, S. , … Messiaen, L. (2007). An absence of cutaneous neurofibromas associated with a 3‐bp inframe deletion in exon 17 of the NF1 gene (c.2970–2972 delAAT): Evidence of a clinically significant NF1 genotype‐phenotype correlation. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 80(1), 140–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyaya, M. , Spurlock, G. , Kluwe, L. , Chuzhanova, N. , Bennett, E. , Thomas, N. , … Mautner, V. (2009). The spectrum of somatic and germline NF1 mutations in NF1 patients with spinal neurofibromas. Neurogenetics, 10(3), 251–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uusitalo, E. , Leppävirta, J. , Koffert, A. , Suominen, S. , Vahtera, J. , Vahlberg, T. , … Peltonen, S. (2015). Incidence and mortality of neurofibromatosis: A total population study in Finland. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 135(3), 904–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson, G. H. (1967). Pulmonary stenosis, cafe‐au‐lait spots, and dull intelligence. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 42(223), 303–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X. , Edmonson, M. N. , Wilkinson, M. R. , Patel, A. , Wu, G. , Liu, Y. , … Zhang, J. (2016). Exploring genomic alteration in pediatric cancer using ProteinPaint. Nature Genetics, 48(1), 4–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information

Supporting information

Supporting information

Supporting information

Supporting information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.