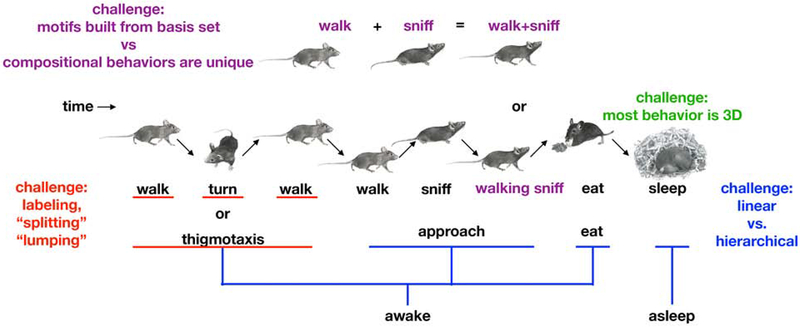

Fig 1. Challenges in computational ethology.

A characteristic sequence of behaviors exhibited by a mouse in its home cage as it thigmotaxis around the walls, approaches some food, eats and then sleeps (center, mouse cartoons). Several key challenges face any segmentation of continuous behavior into components are illustrated. First, the behavior of most model organisms occurs in three dimensions (green). Second, behaviors need to be labeled, which raises the problem of “lumping” versus “splitting” (red); for example, mice thigmotax, a behavior in which mice exhibit locomotion and turning behaviors that are deterministically sequenced to generate an action where the animal circumnavigates its cage. Is thigmotaxis a singular behavior (because its elements are deterministically linked during its expression), or it is a sequences of walking, turning and walking behaviors? Third, should behavior be considered at a single timescale that serially progressed, or instead considered a hierarchical process organized at multiple timescales simultaneously (blue). Fourth, when the mouse is sniffing and running at the same time, is that a compositional behavior whose basis set includes “run” and “sniff,” or is “running+sniffing” a fundamentally new behavior (purple)?