Abstract

While the past two decades have seen rapid advances in research demonstrating links between environmental health and reproductive capacity, African American men have largely been overlooked as study participants. To give voice to the perceptions of urban African American men, the present qualitative study conducted focus groups of men recruited from street- and internet-based advertisements in Washington, DC. Participants were asked for their perspectives on their environment, reproductive health and fertility, and factors that would influence their participation in public health research. Participants expressed concern about ubiquitous environmental exposures characteristic of their living environments, which they attributed in part to gentrification and urban development. Infertility was seen as a threat to masculinity and a taboo subject in the African American community and several participants shared personal stories describing a general code of silence about the subject. Each group offered multiple suggestions for recruiting African American men into research studies; facilitators for study participation included cultural relevance, incentives, transparent communication, internet- and community-based recruitment, and use of African Americans and/or recruiters of color as part of the research team. When asked whether participants would participate in a hypothetical study on fertility that involved providing a sperm sample, there was a mixed reaction, with some expressing concern about how such a sample would be used and others describing a few facilitators for participation in such a study. These are unique perspectives that are largely missing from current-day evidence on the inclusion of African American men in environmental health and reproductive health research.

Keywords: Public health, health care issues, male infertility, physiological and endocrine disorders, qualitative research, Research, male reproductive health, sexuality, men of color, special populations

Environmental contributions to male infertility have been identified in recent years, though African Americans are scarcely included in study populations. Epidemiological evidence suggests that environmental exposures to lead (Telisman et al., 2007), outdoor air pollution (Lafuente et al., 2016), and persistent (Mumford et al., 2015) and nonpersistent endocrine-disrupting chemicals (Zamkowska et al., 2018) are associated with reduced male reproductive capacity including reduced semen quality. African Americans are disproportionately burdened by air pollution compared to Whites due to their relative proximity to urban and industrial facilities (Ard, 2015) and have higher body burdens of endocrine-disrupting chemicals due to a combination of environmental, consumer product, and dietary based exposures (Ruiz et al., 2018). Yet U.S. studies evaluating the association between environmental exposures and male reproductive health tend to have greater than 80% White and between 2% and 10% African American participants, as identified by systematic reviews (Jurewicz et al., 2009; Zamkowska et al., 2018).

Several national and regional survey studies report high levels of concern about environmental pollution among African Americans (Chakraborty et al., 2017; Jones, 1998; Macias, 2015), but few have separately featured the views of men or evaluated perceived health outcomes in relation to pollution concerns. Aside from a few exceptions (Hayward et al., 2015; Mohai & Bryant, 1998; Redwood et al., 2010), studies evaluating neighborhood-based or local environmental concerns of African Americans in urban settings are also limited.

Information from biomedical research on African American infertility is even more sparse, and much of what is known about infertility in the United States is largely characterized by the experiences of European Americans (Ceballo et al., 2015). Limited data exist on the semen parameters of men of color. Studies of fertile and subfertile populations have reported lower semen quality among African Americans (Glazer et al., 2018; Redmon et al., 2013), and from 2006–2010 slightly higher percentages of non-Hispanic Black men reported infertility compared to men of other racial groups in nationally representative samples (Chandra et al., 2013). Whereas the reproductive health of African American men has heavily focused on sexually transmitted disease (STD) risks, there are very few studies on the attitudes and experiences of African American men with infertility (Sherrod & DeCoster, 2011; Taylor, 2018).

To begin addressing these knowledge gaps in an understudied population, the present study explored urban African American male perspectives on (a) their environmental health and (b) their reproductive health in the context of infertility. The current study also examined perceived barriers and facilitators to participating in health research, where African American men continue to be underrepresented (Byrd et al., 2011), particularly in fertility research, which to our knowledge has not previously been examined qualitatively.

Methods

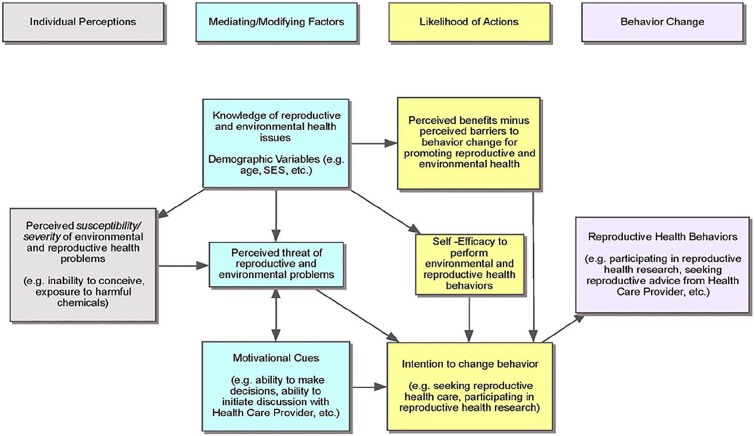

Qualitative research methods were employed through the use of semistructured focus groups. The research team designed a semistructured focus group script specifically for the present study based on concepts from the Expanded Health Belief Model (EHBM; Becker, 1974; Rosenstock et al., 1988; Strecher & Rosenstock, 1997) to ascertain African American perceptions of, barriers to, and self-efficacy for becoming engaged in their environmental and reproductive health (Figure 1). The team then recruited a purposeful sample of African American men. All procedures were approved by The George Washington University Institutional Review Board (IRB; #031523).

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework: Application of the Expanded Health Belief Model to Reproductive and Environmental Health (EHBM).

The conceptual framework of this study was based on the EHBM, a widely used model for explaining change and maintenance of health behavior. The EHBM components include perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action, self-efficacy, and modifying factors. This framework asserts that an individual’s decision to change behaviors (such as taking steps to mitigate his or her exposure to reproductive toxicants in the environment or participating in environmental or reproductive health research) is the result of “cost–benefit” analyses and the individual’s level of self-efficacy.

Recruitment

In June 2015 a full-page-length flyer was created containing age (25–55) and race (African American) inclusion criteria, along with time (120-min sessions), compensation (a $50 gift card and lunch), and researcher contact information. The research team recruited community members directly and did not go through a community advisory board. Initially flyers were posted at IRB-approved locations in front of a community health clinic in Northwest, Washington, DC, and a predominantly African American church in Landover, MD, which did not result in any enrolled participants. In response, the research team transposed the flyer’s contents onto an 18″ × 24″ posterboard and displayed it and distributed modified palm-sized flyers to passersby outside of train stations in Northwest and Southeast Washington, DC. In addition, the research team expanded recruitment to the internet platform Craigslist by placing an advertisement in the “Community Events, Washington, D.C.” section of the website. Interested respondents recruited in person or via the Craigslist ad completed a contact form containing name (or alias) and phone number or email and preferred focus group date of attendance. The research team then contacted the interested respondents, who if still interested were screened for eligibility and signed up for one of three focus group dates. Study enrollees provided their first name (or alias) and phone number or email. No other identifiable personal information was collected.

Initially inclusion criteria restricted age to 25–55 years (e.g., men of “reproductive” or “family planning” age); however, the final study population included five participants who were older than age 55 years because it was believed their views could still be valuable, even though they were outside the study’s initial age criteria. In total, 24 African American males were recruited: 16 from Craigslist and 8 from in-person recruitment.

Focus Groups

Three semistructured focus groups took place at The George Washington University in July and August 2015 with participants who resided in Washington, DC, and surrounding areas. Each group was led by the same African American male moderator and the 3 groups had 7, 11, and 6 participants, respectively. Prior to the commencement of each session, the moderator read aloud the consent form and participants provided written consent. Each focus group was audio recorded while two to three assistants took notes of group activities not captured by the recorder. Participants were given the option to provide an alias for the recording. The moderator asked open-ended questions from the semistructured interview script and facilitated the discussion that followed through the use of probing questions as necessary. The script covered three main subject areas: (a) environmental health, (b) reproductive health within the context of fertility, including reproductive health research, and (b) participation in research, generally. At the conclusion of each session, participants completed a brief demographic questionnaire.

Data Analysis

The audio recordings of the focus groups were transcribed by the research team. Using NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis software®, two coders (LT and FB) independently analyzed the transcripts using an inductive approach and grouped similar codes into concept categories, or themes, which were used to critically analyze and interpret the data for saliency and make conclusions. The coders met to resolve differences. A third coder (NM) independently analyzed the transcripts and manually coded without the use of analysis software and then checked and confirmed these codes against the NVivo coding results.

Results

All participants (n = 24) self-identified as African American; the median age was 47.5 years (Table 1). Participants most commonly reported being never married (n = 11, 45.8%), childless (n = 14, 58.3%), having a college degree (n = 11, 45.8%), and having a household income between $20,000 and $40,000 (n = 10, 41.7%). Table 2 displays a brief summary of the qualitative results, discussed in detail in the following text.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Focus Group Participants (n = 24).

| N respondents (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Median (minimum–maximum) | 47.5 (25–64) |

| 18–29 | 4 (16.7) |

| 30–39 | 3 (12.5) |

| 40–49 | 6 (25.0) |

| 50–59 | 10 (41.7) |

| 60+ | 1 (4.2) |

| Highest level of school completed | |

| 5th to 12th grade, no high school diploma | 3 (12.5) |

| High school graduate, GED or equivalent | 2 (8.3) |

| Some college, no degree | 8 (33.3) |

| College degree | 11 (45.8) |

| Annual household income | |

| Less than 20,000 | 3 (12.5) |

| $20,000–$40,000 | 10 (41.7) |

| $40,000–$60,000 | 3 (12.5) |

| $60,000–$80,000 | 3 (12.5) |

| Greater than $80,000 | 3 (12.5) |

| Refuse to answer | 1 (4.2) |

| Missing | 1 (4.2) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 4 (16.7) |

| Widowed | 1 (4.2) |

| Divorced | 4 (16.7) |

| Separated | 1 (4.2) |

| Never married | 11 (45.8) |

| Living with partner | 2 (8.3) |

| Refuse to answer | 1 (4.2) |

| Number of children | |

| 0 | 14 (58.3) |

| 1–2 | 5 (20.8) |

| 3 or more | 4 (16.7) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Gay | 4 (16.7) |

| Straight | 15 (62.5) |

| Bisexual | 3 (12.5) |

| Something else | 1 (4.2) |

| Refuse to answer/don’t know | 1 (4.2) |

Table 2.

Summary of Themes Identified as Related to the Study’s Primary Research Questions.

| Research question | Theme identified | Examples of identified theme |

|---|---|---|

|

Environmental health What are the perceptions of urban African American men concerning their environmental health? |

Ubiquitous exposures from the built environment | “Yeah because if you look at the correlation with lead paint, and the number of people that may have decreased, uh . . . cognitive thinking skills. I mean, if you look at that, you look at across the board how many people live in housing projects that have lead paint, I mean, if there was a class action lawsuit, the government probably would go broke!” |

| Environmental justice | “That’s always in our community that gets the, the garbage trash, the refinery. They get the old tire places . . . the stuff that we have in our neighborhood, that’s only in our neighborhood.” | |

| Feeling overwhelmed | “Everything is just, everything about life today hurts you in some way, shape, or form. The—the air outside, that ain’t a hundred percent healthy for you to breathe in, you know what I mean? ’Cause you got the car fumes, you got building fumes.” | |

|

Reproductive health What are the perceptions and behaviors of urban African American men concerning their reproductive health? |

Male pride | “Especially a Black man who, who can’t conceive a child. Because, it’s, you know, that’s, that’s, that’s a taboo subject. . . . You’re not going to get a whole lot of conversation from a person who, who can’t conceive. Which is, which is not right. I’m not condoning it. But, that’s just the way it is.” |

| Lack of community support | “I think, particularly in the African American community, we find it very difficult to talk about reproductive health—specifically infertility.” | |

| Children as a cue to action | “If I’m not actively trying to make a child, in my mind I’m like, ‘Well, do I even need to be concerned about my reproductive health, because I’m not trying to reproduce, so why does it matter?’” | |

|

Participation in health research What are facilitators and/or barriers among urban African American men to being recruited for and participating in health research? |

Relevancy | “I was about to walk past you all but then [when] I saw that it was for African American men, I said, ‘Oh, OK, I’ll at least listen to what you have to say at that point.’” |

| Incentives | “Any time you offer some type of incentive, you’re going to have people show up” | |

| Clear, timely message | “I don’t want to hear a ten minute spiel. I think you maybe talked for forty-five seconds.” |

Perceptions of Environmental Health

When asked “What does the phrase ‘environmental health’ mean to you?” participants provided a variety of responses including “toxins and poisons,” “disease,” “brownfields,” “global warming,” “living conditions,” “community support systems,” and the “health” of one’s surrounding area. The moderator then probed aspects relating to the biophysical definition of environment (e.g., air, water, and land) and whether participants saw an interaction between it and human health. During this discussion, the following themes emerged:

Ubiquitous Exposures From the Built Environment

Participants were most commonly concerned about the built environment, specifically, exposures associated with living in an urban area. This included air pollution: “I think about it every time I step out my house, ’cause the cars going past, busses [passing], like dang, you gotta breathe” (Group 1). Chief among their concerns, however, involved old or poorly designed and maintained housing units; participants linked exposures to lead, mold, and other toxins to deteriorating health outcomes: “Well, you still got [housing] projects built with that asbestos paint, lead, all that. You know, schools with that stuff in it. Anything built before 1975, nine times out of ten [it will have] lead, asbestos, stuff like that” (Group 1). Discussions also emerged on health end points:

Participant A: Yeah because if you look at the correlation with lead paint, and the number of people that may have decreased, uh. . .

Participant B: Cognitive?

Participant A: Cognitive thinking skills [agreement in room]. I mean, if you look at that, you look at across the board how many people live in housing projects that have lead paint, I mean, if there was a class action lawsuit, the government probably would go broke! (Group 1)

Said a participant on mold, “Mold makes you sick. You can die from it. People just claiming, ‘Oh, just wipe it away and that’s it.’ Like, no. That’s not really the way it works” (Group 3).

Environmental Justice

Participants discussed the proximity of lower socioeconomic status neighborhoods to larger polluting sources. Housing marketed as alluring, “nice,” and “cheap” was seen as often located near some “chemical” or “nuclear waste-type thing” (Group 3). As a result, there was a pervading sentiment that generally African American communities were exposed to a far greater number of harmful environmental substances than White communities were. Said one participant: “That’s always in our community that gets the, the garbage trash, the refinery. They get the old tire places . . . the stuff that we have in our neighborhood, that’s only in our neighborhood” (Group 2). Participants also noted a general dearth of environmentally friendly spaces in their communities compared to areas of higher socioeconomic status. Several mentioned that city development of green spaces and parks would only occur as the neighborhood became gentrified: “So every community that is being [brought into] our Black community, as we are being moved out, and the area [is] being redeveloped, there are [then] environmental things [put] in place” (Group 2). A few joked that as their communities gentrified, the upkeep of local dog parks received equal if not greater attention than recreational areas of their neighborhoods:

Participant A: And, you know, I can recall a time in D.C. where, [if] your dog pooped, you kept on going. You know, you better not do that today, in this city. [Laughter in room]

Participant B: And I agree with that, I agree with that. You can’t even walk in the grass.

Participant C: You know, they got plenty of places to put a dogs’ playground as opposed to a kids’ playground. [Laughter in room] (Group 1)

Feeling Overwhelmed

Participants generally expressed feeling overwhelmed by their environmental exposures and at a loss for ways to address environmental health problems:

Everything is just, everything about life today hurts you in some way, shape, or form. The—the air outside, that ain’t a hundred percent healthy for you to breathe in, you know what I mean? ’Cause you got the car fumes, you got building fumes. (Group 1)

As stated by a younger participant, “It’s just like in relation to the environment, can we actually make a difference, is the thing” (Group 3). While participants mentioned additional concerns such as drinking water quality and climate change, the clearest emerging theme from all three groups involved the difficulty in coping with ubiquitous pollution from urban living.

Perceptions of Reproductive Health

When asked “What comes to mind when you hear, ‘reproductive health?’” a majority of participants mentioned “sex” and “children.” Other responses included “test-tube babies,” “sexual education,” and “sexually transmitted infections.” Through probing factors that would encourage or discourage engaging in one’s reproductive health, three major themes emerged:

Male Pride

A majority of participants viewed the ability to induce pregnancy as a source of male pride. As such, many were fearful of “feeling like less than a man” (Group 1) if needing to divulge a fertility problem to a spouse, family member, or physician. Further, several participants viewed the concept of masculinity as especially important for African Americans, discouraging their willingness to disclose a fertility complication:

Especially a Black man who, who can’t conceive a child. Because, it’s, you know, that’s, that’s, that’s a taboo subject. That’s really taboo. You’re not going to get a whole lot of conversation from a person who, who can’t conceive. Which is, which is not right. I’m not condoning it. But, that’s just the way it is. (Group 2)

Said another participant, “I think it’s some kind of stereotype that Black men are supposed to be very manly and just carry around this image” (Group 1). Relating to this threat to male pride was a general reluctance to seek medical treatment. Younger participants, in particular, said that if a fertility problem emerged between them and their female partner, they would push for their partner to get it checked first. Upon being asked if he and his girlfriend sought medical treatment for a fertility complication, a participant responded, “That’s bad news, see. I want her to go first and see if it’s her and if it’s not her. . . . Because I’ll feel better if knowing if it’s her or not, than me just going in there” (Group 3). Others in the group shared similar experiences:

He’s not even the first guy that said that he would rather the female goes [to get checked] first because even when it came to my uncle and my father they wanted their girlfriends to go first before they went. One of the times it actually ended up being the man but it does affect your confidence and men need that type of thing in order to carry on with a lot of the day-to-day life. (Group 3)

Overall, many participants associated the ability to reproduce with self-worth and manhood: “We have the gift to reproduce. It’s almost like fulfilling something when you have kids” (Group 3).

Lack of Community Support

Participants largely agreed that discussing reproductive health was taboo in the African American community. “I think, particularly in the African American community, we find it very difficult to talk about reproductive health—specifically infertility” (Group 1). Several felt that they could disclose a suspected infertility problem to few individuals beyond their spouse. Others cited the influence of religion or the faith-based community as a barrier: “People act like, just pray on it,” said one participant (Group 2). Another participant noted a lack of dialogue among couples at his church on the subject:

When my wife and I first found out that we were having fertility issues, we told a couple [of] confidants, you know our close friends, our pastor, you know, family members—certain family members [but] not all of them . . . [laughs]. And so, the pastor, he was like, “Well, there’s a couple of families in the church who have experienced the same issues but none of them actually want to talk to us.” (Group 1)

The participant went on to depict the underrepresentation of African Americans at a fertility clinic he and his wife attended.

Children as a Cue to Action

Many participants recalled only actively engaging in their reproductive health if attempting to conceive: “If I’m not actively trying to make a child, in my mind I’m like, ‘Well, do I even need to be concerned about my reproductive health, because I’m not trying to reproduce, so why does it matter?’” (Group 1). Younger participants tended to think about their reproductive health when pregnancy did not occur after unprotected intercourse, despite pregnancy not being a desired outcome of the sexual experience:

Participant A: There would be times when she wasn’t on birth control and we’d have unprotected sex and I’d be like am I shooting blanks? Because I’ve been ejaculating inside of her and nothing’s happened. So that had me thinking about it.

Participant B: I was in a relationship for four years. We weren’t trying to have kids or anything but we would have, just like he was saying, unprotected sex here and there and nothing would happen. That’s kind of when it clicked, like am I, am I all the way there or. . .? But it just wasn’t a topic of conversation because we weren’t trying to have kids at that time.

Participant C: Well me myself, to piggy back on what them brothers said, I was the same way until . . . I went [to seek medical treatment] before the female. So come to find out like I said shooting blanks, [and] two years later I’m like what’s wrong with me. I’ve been with this girl for four years and nothing happened. So I finally went to the doctor; they told me I was unable to conceive children. So I’ve been living with this for about nine years now. (Group 3)

Although a handful of participants recalled an infertility experience, many attributed male pride and community stigma as barriers to engaging in their reproductive health.

Perceptions of Participating in Reproductive Health Research

When asked hypothetically if they would be “willing to participate in a reproductive health research study,” most participants were initially open to the idea if privacy stipulations were met. Others were less enthusiastic. The moderator then probed the idea of submitting a semen sample for such a study and as the discussion matured, several items of concern emerged:

Sperm Sample Security

More than half of participants in each focus group voiced concerns over their samples being stored securely and in accordance with their consent. The following exchange from Focus Group 1 summarized the sentiment from all three groups:

Participant A: I mean, if I’m going to give you my sperm, I want to know what you gonna do with it!

Participant B: Yeah, I need to see a lot of that in writing too—exactly how it’s going to be used, and what the limits are and everything.

Participant C: Yeah, and the only thing I would add to those two . . . I would want them to be term-limited on the research project. Because let’s say that this research goes for twenty years—my sperm may last for fifty years [some agreement in room]. And you sell it after that and there’s a baby. (Group 1)

Many participants echoed concerns of sample misuse leading to lifelong consequences—mainly, unintended offspring. Others perceived potential misuse as part of a planned conspiracy:

Participant E: Well for me personally, I already know—the government [is] doing that right today. They create—they getting sperm samples from dudes and eggs from females and making whatever they want to make out of it.

Participant F: Cloning.

Participant G: Yeah, that’s exactly what it’s called. (Group 1)

Reservations Around the Term “Research”

Relating to concerns of sample misuse, multiple participants were skeptical of study investigators using sperm samples “for research.” Several believed that this gave investigators leeway to use the samples in a manner unrelated to participant consent: “You say research, but it could be circumvented to go into someone else’s pocket in a certain sperm bank. And I don’t want to find in ten years I’ve got fifty kids or whatever” (Group 2). By contrast, participants had a clearer understanding of the idea that a “sperm bank” would be explicitly used to induce pregnancy.

Reluctant Willingness to Participate

Despite the above concerns, participants were generally open to taking part in a reproductive health study if given assurances that their privacy would be protected, their samples stored securely, and a financial incentive be provided. Several mentioned the benefits of knowing their fertility status or furthering community knowledge as reasons to participate. But in most cases, there was a feeling of hesitancy attached to the willingness: “I definitely would want to help out for research. . . . But I guess it’s just this thing with me that that’s like your life line that you’ve given away.” (Group 3). A participant from the same focus group agreed: “I’d be open to it. . . . But I would want it to be confidential. I don’t even want anybody to know I went there” (Group 3). Underlying embarrassment of submitting a sperm sample, coupled with skepticism as to its future use, led to some feelings of ambivalence toward taking part in reproductive health research.

Perceived Barriers and Facilitators to Health Research Participation

Fourteen participants had participated in prior research, and n = 9 had participated in health-related research. When asked about best practices for recruiting African American men into health research, for the present study and generally, the following themes emerged:

Relevancy

Participants cited the present study’s relevance to African American men as a primary motivator. Several saw their participation as an act from which other African American men could benefit. As one participant said, “This one was more for my culture. I can relate to this. So, I definitely want to be hands-on” (Group 3). In recalling his experience being street recruited for the present study, another participant said: “I was about to walk past you all but then [when] I saw that it was for African American men, I said, ‘Oh, OK, I’ll at least listen to what you have to say at that point’” (Group 1). Others saw their participation as an opportunity to gain knowledge. For those who had taken part in studies previously, that the present study featured African American men was unique, and several expressed surprise that it was run by some investigators of color or that they were not the only African American present:

It’s just that, it’s never been brought to them, with people of color being of concern. And . . . I would think that, more Black people, Black men would be interested, as long as they know they’ve got other Black men [are] coming in to contribute. (Group 2)

Along these lines, many participants conveyed the importance of establishing recruiter presence in their communities and using strategies that target African American men: “You got to go to where the brothers are if you want to get the brothers” (Group 2). These strategies included the use of the internet and/or social media as recruiting mediums and barbershops or recreational centers as recruitment sites. Additionally, many participants voiced their preference for recruiters or researchers of color: “I would say, if it’s going to be to benefit Black men, then it really makes a difference for me if some or most of the people recruiting me are Black men. Or at least men of color, you know” (Group 1).

Incentives

Nearly all participants highlighted the $50 monetary incentive as a motivation to take part in the present study and recommended incentives, monetary or otherwise (e.g., lunch) as a general recruitment strategy: “Any time you offer some type of incentive, you’re going to have people show up” (Group 2).

Timely, Clear Message

When asked about positive and negative recruitment methods they encountered, participants attributed positive in-person recruitment efforts as “short,” with small handouts of clear instructions containing a minimal amount of text and clear indication of the accompanying incentive, time commitment, and location: “I don’t want to hear a ten minute spiel. I think you maybe talked for forty-five seconds” (Group 1). Regarding negative experiences and methods, said one participant, “You can hold on to the condescending, arrogant individuals who think they are blessing us” (Group 2). Overall, participants cited the importance of the perceived attitude of recruiters and researchers, the need for recruiters to be direct and transparent in laying out time expectations, specific next steps, and incentives included, as well as the utility of internet- and community-based recruitment methods.

Discussion

Despite numerous documented environmental threats, African American men are rarely included as participants in studies evaluating the association between environmental exposures and reproductive health. The present study utilized focus groups to evaluate urban African American male attitudes and behaviors concerning their environmental health, reproductive health, participation in research, and participation in reproductive health research. The study’s findings enumerate the following three research recommendations:

Recommendation 1: Additional research is needed on perceptions of infertility in African American men and on “Black masculinity.”

Perceptions about infertility have rarely been evaluated in African American communities (Ceballo et al., 2015; Inhorn et al., 2012), and this is particularly true among African American men, who tend to be evaluated through the lens of STD risks. In the present study, participants referred to infertility as a taboo subject and a threat to male pride and masculinity. Among participants who experienced infertility, the combination of these factors led to a reluctance to seek treatment or disclose the issue within inner family or social circles. These results align with the scant existing qualitative literature on African American men and women, which reports a general code of silence on the subject. Male partners among six married African American couples who experienced infertility reported stoicism, inadequacy, and low self-esteem from being unable to fulfill the role as a procreator and man (Taylor, 2018). Comparable themes of impaired gender identity and self-worth, silence, and isolation were reported by Midwestern African American women with infertility (n = 50) in an interview study thought to be one of the first to sample exclusively from this population (Ceballo et al., 2015).

Related to the view of infertility as a threat to male pride in the present study was its effect on “Black masculinity,” implying a distinct characterization of masculinity that one study participant labeled a stereotype. Multiple authors have explored masculinity as being important or enhanced for African American men (Bowleg et al., 2011; Ward, 2005; Whitehead, 1997) whether to combat societal stigma, discrimination, and racism (Whitehead, 1997) or to exhibit personal responsibility and “life control” (Hammond & Mattis, 2005). In the field of reproductive health, Black masculinity has been studied as a potential behavioral influence for sexually risky behavior (Bowleg et al., 2011) and may be one contributor to African American men being “pigeonholed” into studies on STD risk. To our knowledge very few studies to date have explored the concept of Black masculinity in the context of infertility, although it likely plays a role in the cultural silence around the issue. The present study did not evaluate this characterization in depth, but it may relate to the stereotypical belief that emerged in Ceballo’s and Taylor’s interviews of African American women (n = 50) and couples (n = 6), respectively, that impaired fertility was not presumed to be an issue of their community—a view that existed regardless of socioeconomic status (Ceballo et al., 2015; Taylor, 2018).

Recommendation 2: Additional studies are needed on perceptions of environmental health and proximity to “environmental goods” in African American communities.

Few studies have evaluated urban African American perceptions of local or neighborhood environmental exposures and their association with health outcomes. In the present study, participants were highly concerned about ubiquitous exposures from their built urban living environments, such as air pollution, lead, and mold, to which there was some linkage to adverse health outcomes. Similar themes were reported in a few small focus groups comprising mostly of African American women, which sampled lower income or public housing residents and reported health concerns about trash, rodents, water, and sewage leaks (Hayward et al., 2015; Redwood et al., 2010).

Participants in the present study also discussed being located disproportionately near environmental harm such as trash, refineries, and other sources of industrial pollution compared to White communities. Similar themes related to environmental justice (EJ) have been reported in a body of national and regional survey-based literature on African American environmentalism. These studies largely report environmental risk perception of African American men and women to be on par with, if not higher than, that of Whites (Chakraborty et al., 2017; Finucane et al., 2000; Jones, 1998; Macias, 2015; Mohai & Bryant, 1998).

What differentiates the present study from traditional EJ literature is the participant discussion that also emerged about their lack of access to environmental goods common to more affluent, White urban neighborhoods, such as green space and parks. The disproportionate access to these urban environmental goods based on income and race is a continuing EJ issue in the United States that has been documented in studies of metropolitan areas, including Washington, DC (Chuang et al., 2017; Schwarz et al., 2015). Participants in the present study attributed this trend to the gentrification of their neighborhoods. Despite the well-known benefit of green space as an environmental amenity that benefits health, the “greening” of many cities may in fact fuel the cycle of gentrification by increasing housing prices and is why some researchers recommend a more cautious and nuanced approach toward urban greening (Cole et al., 2017; Maantay & Maroko, 2018). Further research is needed on the perception of the ongoing “green gentrification” trend in U.S. cities that encompass the views of African Americans and communities of color, particularly those of lower incomes.

Recommendation 3: To address knowledge gaps involving African American men, researchers should prioritize community access to health research opportunities using active and culturally sensitive recruitment strategies.

A preponderance of literature has evaluated the attitudes of African American men and women toward participation in research, though comparatively few feature the views of men, who continue to be underrepresented (Byrd et al., 2011). In the present study most men had taken part in prior research (n = 14) or health research (n = 9), indicating a general willingness toward research that has been reported in studies of African American men elsewhere (Byrd et al., 2011; Woods et al., 2004).

In addition to establishing recruiter presence in African American communities, active and culturally sensitive recruitment approaches should be used to increase enrollment. In the present study, the passive posting of flyers in African American–concentrated areas did not result in any enrollees. It was only when the research team actively street recruited using a large posterboard to better recognize initial interest from passersby and foster a personal, face-to-face interaction that study enrollment improved. Further, the use of Craigslist was surprisingly effective as it accounted for two thirds of enrollment. Participants mentioned as additional facilitators the present study’s use of a culturally relevant study topic, incentives, transparent communication, and use of African Americans and/or recruiters of color as part of the research team. Studies and reviews elsewhere have noted the usefulness of these approaches to improve participation among African Americans (George et al., 2014) and African American men (Byrd et al., 2011; Woods et al., 2004), and authors recommend using a combination of these techniques as opposed to a single approach (Woods et al., 2004). Finally, the present study’s sole focus on African American men appeared to cultivate a good rapport among participants.

Despite favorable attitudes in the present study toward health research, participants were more hesitant about the term “research” when asked about submitting a semen sample for a hypothetical reproductive health study. This speaks to the responsibility of the research team to be transparent and to the potential influence of a study’s design on participation. Researchers must also deconstruct sources of mistrust that have been the source of negative perceptions of research reported elsewhere among African American men and women (Corbie-Smith et al., 1999; Freimuth et al., 2001). Some of these perceptions, which also include feelings of being “experimented on” and lack of researcher transparency, are fueled by knowledge of the 40-year human atrocities of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study (TSS) committed by the U.S. Public Health Service on poor African American men (Corbie-Smith et al., 1999; Freimuth et al., 2001). Studies have also reported researcher mistrust irrespective of TSS knowledge (Brandon et al., 2005) as well as among African Americans who had experience as prior research participants (Scharff et al., 2010).

This study’s generalizability is limited by the use of a convenience sample of 24 men, which was due to a limited time frame. Though some findings are in line with existing literature, they are not generalizable to all urban African American men. Street recruitment did not occur across all wards of Washington, DC, and thus likely missed important segments of the study population. Generally, discussion did not delve into perceptions of a link between environmental exposures and reproductive health. Despite attempts to include a large enough share of street-recruited participants, most enrollees discovered the study via Craigslist. As a result, the present study may have unintentionally selected for men who had access to the internet and/or were prone to search the website for study- or incentive-based opportunities. A $50 monetary incentive may seem high compared to other focus group studies, though according to federal data the District of Columbia had the second highest cost of living nationally in 2015 (“Real Personal Income for States and Metropolitan Areas, 2015,” 2017). Still, researchers should take care to avoid incentives that could coerce lower income individuals to participate (Freimuth et al., 2001). Participant income status was unknown during recruitment; however, the majority (54%) of participants had incomes less than $40,000 (Table 1).

A major strength of this study is the originality of the topics and narratives that were collected from this understudied population. Few studies have evaluated qualitative views of infertility among African American men, and the present study may be the first to examine attitudes toward taking part in a fertility study that includes the submission of a semen sample. Of the larger bodies of literature on African American environmental attitudes and participation in research, comparatively few feature men or mention perceived health outcomes, and the focus group structure allowed for an examination of nuance for all three topics. As such this study, though exploratory, offers a glimpse into what remain large knowledge gaps.

Conclusions

To give voice to African American men who are not typically included in studies on environmental exposures and reproductive health, the present study explored their perceptions on these topics as well as participation in research. Amid existing environmental and reproductive health disparities affecting African American men, further study on these topics is needed.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Nathan McCray  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6194-5874

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6194-5874

References

- Ard K. (2015). Trends in exposure to industrial air toxins for different racial and socioeconomic groups: A spatial and temporal examination of environmental inequality in the U.S. from 1995 to 2004. Social Science Research, 53, 375–390. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker M. H. (1974). The health belief model and sick role behavior. Health Education Monographs, 2(4), 409–419. [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L., Teti M., Massie J. S., Patel A., Malebranche D. J., Tschann J. M. (2011). ‘What does it take to be a man? What is a real man?’: Ideologies of masculinity and HIV sexual risk among Black heterosexual men. Cult Health Sex, 13(5), 545–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon D. T., Isaac L. A., LaVeist T. A. (2005). The legacy of Tuskegee and trust in medical care: Is Tuskegee responsible for race differences in mistrust of medical care? Journal of the National Medical Association, 97(7), 951–956. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd G. S., Edwards C. L., Kelkar V. A., Phillips R. G., Byrd J. R., Pim-Pong D. S., Starks T. D., Taylor A. L., Mckinley R. E., Li Y. J., Pericak-Vance M. (2011). Recruiting intergenerational African American males for biomedical research Studies: A major research challenge. Journal of the National Medical Association, 103(6), 480–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceballo R., Graham E. T., Hart J. (2015). Silent and infertile: An intersectional analysis of the experiences of socioeconomically diverse African American women with infertility. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 39(4), 497–511. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty J., Collins T. W., Grineski S. E., Maldonado A. (2017). Racial differences in perceptions of air pollution health risk: Does environmental exposure matter? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(2), 116. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14020116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra A., Copen C. E., Stephen E. H. (2013). Infertility and impaired fecundity in the United States, 1982–2010: Data from the National Survey of Family Growth. National Health Statistics Reports, (67), 1–18, 11 p following 19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang W.-C., Boone C. G., Locke D. H., Grove J. M., Whitmer A., Buckley G., Zhang S. (2017). Tree canopy change and neighborhood stability: A comparative analysis of Washington, D.C. and Baltimore, MD. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 27, 363–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2017.03.030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cole H. V. S., Garcia Lamarca M., Connolly J. J. T., Anguelovski I. (2017). Are green cities healthy and equitable? Unpacking the relationship between health, green space and gentrification. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 71(11), 1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbie-Smith G., Thomas S. B., Williams M. V., Moody-Ayers S. (1999). Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 14(9), 537–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finucane M. L., Slovic P., Mertz C. K., Flynn J., Satterfield T. A. (2000). Gender, race, and perceived risk: The ‘white male’ effect. Health, Risk & Society, 2(2), 159–172. [Google Scholar]

- Freimuth V. S., Quinn S. C., Thomas S. B., Cole G., Zook E., Duncan T. (2001). African Americans’ views on research and the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Social Science and Medicine, 52(5), 797–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George S., Duran N., Norris K. (2014). A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. American Journal of Public Health, 104(2), e16–e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazer C. H., Li S., Zhang C. A., Giwercman A., Bonde J. P., Eisenberg M. L. (2018). Racial and sociodemographic differences of semen parameters among US men undergoing a semen analysis. Urology, 123, 126–132. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2018.09.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond W. P., Mattis J. S. (2005). Being a man about it: Manhood meaning among African American men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 6(2), 114–126. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward E., Ibe C., Young J. H., Potti K., Jones P., 3rd, Pollack C. E., Gudzune K. A. (2015). Linking social and built environmental factors to the health of public housing residents: A focus group study. BMC Public Health, 15, 351–351. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1710-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inhorn M. C., Ceballo R., Nachtigall R. (2012). Marginalized, invisible, and unwanted: American minority struggles with infertility and assisted conception. In L. Culley, N. Hudson, & F. Rooij (Eds.), Marginalized Reproduction: Ethnicity, Infertility and Reproductive Technologies (pp. 181–197). London, England: Earthscan. [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. E. (1998). Black concern for the environment: Myth versus reality. Society & Natural Resources, 11(3), 209–228. [Google Scholar]

- Jurewicz J., Hanke W., Radwan M., Bonde J. P. (2009). Environmental factors and semen quality. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health, 22(4), 305–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafuente R., Garcia-Blaquez N., Jacquemin B., Checa M. A. (2016). Outdoor air pollution and sperm quality. Fertility and Sterility, 106(4), 880–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maantay J. A., Maroko A. R. (2018). Brownfields to greenfields: Environmental justice versus environmental gentrification. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(10), 2233. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15102233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macias T. (2015). Environmental risk perception among race and ethnic groups in the United States. Ethnicities, 16(1), 111–129. [Google Scholar]

- Mohai P., Bryant B. (1998). Is there a “race” effect on concern for environmental quality? Public Opinion Quarterly, 62(4), 475–505. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford S. L., Kim S., Chen Z., Gore-Langton R. E., Boyd Barr D., Buck Louis G. M. (2015). Persistent organic pollutants and semen quality: The LIFE Study. Chemosphere, 135, 427–435. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Real Personal Income for States and Metropolitan Areas, 2015. (2017). [Press release]. https://www.bea.gov/news/2017/real-personal-income-states-and-metropolitan-areas-2015

- Redmon J. B., Thomas W., Ma W., Drobnis E. Z., Sparks A., Wang C., Brazil C., Overstreet J. W., Liu F., Swan S. H., & Study for Future Families Research Group. (2013). Semen parameters in fertile US men: The Study for Future Families. Andrology, 1(6), 806–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redwood Y., Schulz A. J., Israel B. A., Yoshihama M., Wang C. C., Kreuter M. (2010). Social, economic, and political processes that create built environment inequities: Perspectives from urban African Americans in Atlanta. Family and Community Health, 33(1), 53–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock I. M., Strecher V. J., Becker M. H. (1988). Social learning theory and the Health Belief Model. Health Education Quarterly, 15(2), 175–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz D., Becerra M., Jagai J. S., Ard K., Sargis R. M. (2018). Disparities in environmental exposures to endocrine-disrupting chemicals and diabetes risk in vulnerable populations. Diabetes Care, 41(1), 193–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharff D. P., Mathews K. J., Jackson P., Hoffsuemmer J., Martin E., Edwards D. (2010). More than Tuskegee: Understanding mistrust about research participation. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 21(3), 879–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz K., Fragkias M., Boone C. G., Zhou W., McHale M., Grove J. M., O’Neil-Dunne J., McFadden J. P., Buckley G. L., Childers D., Ogden L., Pincetl S., Pataki D., Whitmer A., Cadenasso M. L. (2015). Trees grow on money: Urban tree canopy cover and environmental justice. PloS One, 10(4), e0122051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrod R. A., DeCoster J. (2011). Male infertility: An exploratory comparison of African American and white men. Journal of Cultural Diversity, 18(1), 29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strecher V. J., Rosenstock I. M. (1997). The Health Belief Model Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor L. C. (2018). The Experience of Infertility Among African American Couples. Journal of African American Studies, 22(4), 357–372. doi:10.1007/s12111-018-9416-6. [Google Scholar]

- Telisman S., Colak B., Pizent A., Jurasovic J., Cvitkovic P. (2007). Reproductive toxicity of low-level lead exposure in men. Environmental Research, 105(2), 256–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward E. G. (2005). Homophobia, hypermasculinity and the US black church. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 7(5), 493–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead T. L. (1997). Urban low-income African American men, HIV/AIDS, and gender identity. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 11(4), 411–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods V. D., Montgomery S. B., Herring R. P. (2004). Recruiting Black/African American men for research on prostate cancer prevention. Cancer, 100(5), 1017–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamkowska D., Karwacka A., Jurewicz J., Radwan M. (2018). Environmental exposure to non-persistent endocrine disrupting chemicals and semen quality: An overview of the current epidemiological evidence. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health, 31(4), 377–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]