Abstract

Introduction

Psoriasis is a T cell-mediated inflammatory skin disease in which fatty acids may be a link between psoriasis and its comorbidity.

Aim

The present meta-analysis aimed to evaluate lipid, lipoprotein, and apolipoprotein levels in the psoriatic patients compared with the control subjects.

Material and methods

Four databases, including Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, and Cochrane Library were searched until July 2017. All records analysed were case-control studies. The quality of the questionnaires was evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). A random-effects meta-analysis was done by Rev Man 5.3 using mean difference (MD) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

Out of 580 studies identified in four databases, 49 studies were included and analysed in this meta-analysis. The results showed that MD of total cholesterol, triglyceride, LDL, VLDL, HDL, Lp(a), Apo A1, and Apo B levels in the patients compared with the controls were (MD = 13.74 mg/dl; 95% CI: 7.72–19.75; p< 0.00001), (MD = 26.04 mg/dl; 95% CI: 20.77–31.31; p< 0.00001), (MD = 11.41 mg/dl; 95% CI: 6.26–16.57; p< 0.0001), (MD = 4.82 mg/dl; 95% CI: 3.63–6.00; p< 0.00001), (MD = –2.78 mg/dl; 95% CI: –4.53 – –1.03; p< 0.002), (MD = 8.51 mg/dl; 95% CI: 4.86–12.17; p< 0.0001), (MD = –6.60 mg/dl; 95% CI: –13.96 – 0.75; p< 0.08), and (MD = 9.70 mg/dl; 95% CI: 3.02–16.39; p< 0.004), respectively.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis identified abnormality of serum lipid, lipoprotein, and apolipoproteinprofiles in psoriatic patients compared with the controls as well as possibly a greater risk of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular (CV) accidents in the patients.

Keywords: psoriasis, serum, lipid, lipoprotein, apolipoprotein

Introduction

Psoriasis is one of the most common T cell-mediated inflammatory skin diseases with an unknown aetiology and a prevalence of about 1–3% in the general population [1–3]. Psoriasis can be caused by the combined effects of genetic and environmental factors on the immune system [4].The disease is associated with abnormal plasma lipid metabolism and oxidative stress [3].Psoriasis is accompanied by metabolic disturbances and cardio-metabolic disorders, and fatty acids may be a link between psoriasis and its comorbidity [5].Inflammatory activity in psoriasis acts independently as a cardiovascular (CV) risk factor [6].In psoriatic patients, lipid abnormalities are correlated with increased mortality due to myocardial infarction and stroke [7].Psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) score is used to grade the cases into mild, moderate, and severe. This score is considered outstanding when severe cases are involved. It also provides an advantage for a large base of studies in which it has been used for comparison [8]. The severity of psoriasis is correlated with body mass index (BMI), especially with abdominal fat, which represents the source of production of a complex network of adipokines [2].Plasma lipoproteins, besides their important role in the bulk transport of lipids, are also involved in maintaining a proper lipid composition of cell membranes [9].The plasma concentration of the major apoprotein of low-density lipoprotein (LDL), apolipoprotein B (Apo B), is frequently increased in patients with coronary disease, while apolipoprotein A1 (Apo A1), the major protein component of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) is an antiatherogenic factor [10].Apo B transports all potentially atherogenic very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), intermediate-density lipoprotein, and LDL particles [11].

Aim

The aim of the present meta-analysis was the evaluation of lipid, lipoprotein, and apolipoprotein levels in the psoriatic patients compared with the control subjects.

Material and methods

This meta-analysis was designed based on the guidelines for the preferred reporting items of the systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA statement) [12].

Search strategies

Four databases, including Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, and Cochrane Library were searched for evaluation of serum lipid, lipoprotein, and apolipoprotein levels in psoriatic patients using the search terms “lipid or lipoprotein or apolipoprotein”, “psoriasis”, and “serum”. The search was done for publications until July 2017.

Study selection

The studies were searched for assessment of serum lipid, lipoprotein and apolipoprotein profiles of psoriatic patients compared with the healthy controls in English abstracts. Studies were included if they were case-control ones with two groups (psoriatic patients and healthy controls), they evaluated the serum profile, including the mean/median lipid or lipoprotein levels, the healthy controls did not have any systemic or other relevant skin diseases, and the patients had just psoriasis; studies including patients with psoriatic arthritis were excluded. Reviews, letters to editor or case reports, and studies not having full-text, not reporting mean or median of serum levels, or having no relevant data were excluded from the analysis. The exclusion criteria in most studies for the psoriatic patients and controls included concomitant diseases potentially disturbing lipid metabolism (i.e. CV, hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), thyroid gland disorders, nephrotic syndrome, chronic kidney failure, and obstructive liver disease), any systemic medication known to affect lipid metabolism or evaluate immunological parameters for a specified period and studies including patients with a recent history of infections.

Data extraction from studies

Three authors did the process of data extraction. The first author (M.S.) searched the studies and screened titles and abstracts of every study based on the above-mentioned criteria and extracted data. The second author (M.R.) independently re-checked the full texts of screened studies. Data collected for every study included the first author, year of publication, journal, country, sample size of patients and controls, percentage of male patients and controls, mean age of patients and controls, BMI of patients and controls, mean PASI of patients, serum total cholesterol, triglyceride (TG), LDL, HDL, VLDL, lipoprotein a (Lp(a)), Apo A1, and Apo B levels of patients and controls. Lipid and lipoprotein levels were measured by the standard enzymatic method in most studies and mean values were expressed in mg/dl. The third author (E.Z.) resolved the disagreement between the two previous authors.

Quality evaluation

The quality of the questionnaires was evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) with a total score of nine for every study, 7–9 as high quality, 4–6 as medium quality, and 0–3 as low quality [13]. The quality of every study was evaluated by two authors (M.R. & M.S.) by reaching a consensus via discussion. Therefore, a study with a score ≥ 7 was found to have a high quality.

Statistical analysis

A random-effects meta-analysis was done by Review Manager 5.3 (Rev Man 5.3, The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, United Kingdom) using mean difference (MD) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The Q and I2 statistics were used to assess heterogeneity between the estimates. For the Q statistic, heterogeneity was considered if p< 0.1, and p-value (2-sided) < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in other analyses. In addition, publication bias was assessed through funnel plot analysis along with Begg’s and Egger’s tests. We used a formula for estimation of mean and SD if the study reported median plus range and for estimation of SD if the study reported standard error (SE) [14, 15].The units of serum lipid and lipoprotein levels were mg/dl. In a number of studies, the VLDL level was estimated by the formula VLDL = triglyceride/5.

Results

Literature search

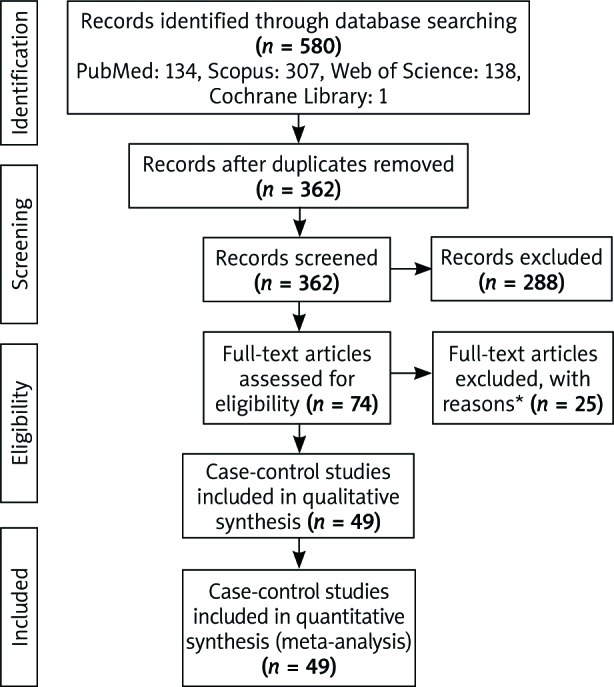

Out of 580 studies identified in four databases, after removing the duplicate ones, 362 studies were screened (Figure 1). Among these, 288 studies were excluded because they were not relevant, and 74 studies were evaluated for eligibility. At last, 25 other studies were excluded for reasons reported in Figure 1, so a total number of 49 studies were included and analysed in meta-analysis.

Figure 1.

Flow-chart of the stud

The studies were published between 1989 and 2017. The meta-analysis included 2600 psoriatic patients and 2358 healthy controls. The mean age of patients was 40.89 years (range: 26.03–49.70 years) and that of healthy controls 39.64 years (range: 23.40–49.48 years). Thirteen studies were reported from Turkey [16–28], eight from Iran [11, 29–35],seven from India [36–42],five from Poland [5, 43–46], three from the USA [47–49],two from Spain [2, 10],Japan [50, 51],Egypt [52, 53],and Italy [54, 55],one from Austria [56],Romania [1],Portugal [57],Iraq [58],and China [59].Three studies [5, 47, 56]reported the median and one study [57]reported SE, which were converted to mean and SD, respectively. A full description of the examined studies can be found in Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Figure S1.

Supplementary Table S1

Supplementary Figure S1

Lipid and lipoprotein profiles

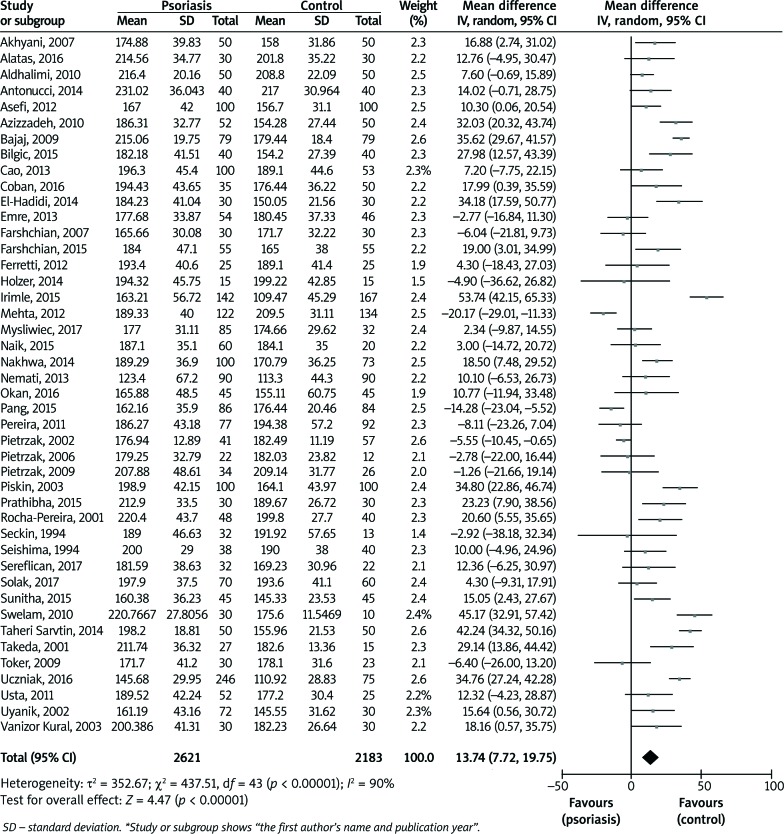

The pooled analysis showed that MD of studies reporting serum total cholesterol levels in psoriatic patients compared with healthy controls was 13.74 mg/dl (95% CI: 7.72–19.75; p< 0.00001), with heterogeneity of 90% (Figure 2). The results showed that the mean total cholesterol level was significantly higher in the patients than the controls.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of random-effects model of serum total cholesterol levels in psoriatic patients compared with healthy controls

The pooled MD for comparison of serum TG levels in the psoriatic patients compared with the controls was 26.04 mg/dl (95% CI: 20.77–31.31; p< 0.00001), with heterogeneity of 74% (Figure 3). The result showed that the triglyceride level in the patients was significantly higher than in the controls.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of random-effects model of serum triglyceride (TG) levels in psoriatic patients compared with healthy controls

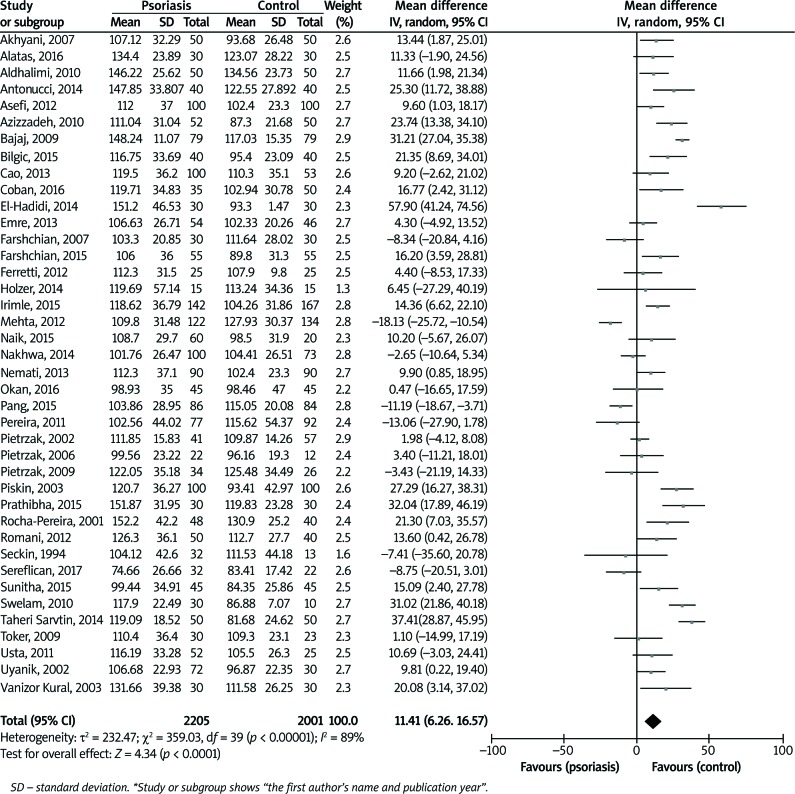

Figure 4 shows the mean levels of LDL in the patients compared with the controls. The pooled MD was 11.41 mg/dl (95% CI: 6.26–16.57; p< 0.0001) with heterogeneity of 89%. Therefore, the LDL level was significantly higher in the patients than in the controls.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of random-effects model of serum low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels in psoriatic patients compared with healthy controls

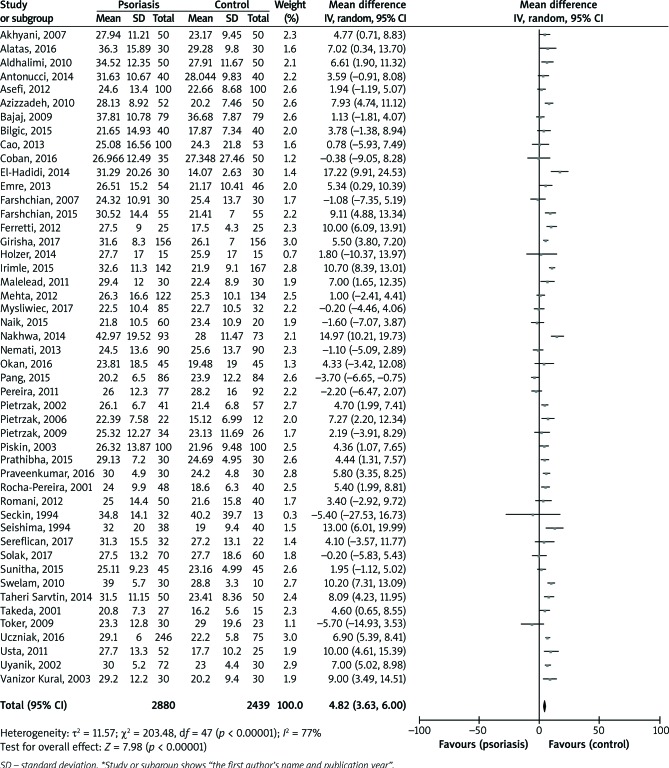

A random-effects meta-analysis of serum VLDL levels in the psoriatic patients compared with the controls is shown in Figure 5. The pooled MD was 4.82 mg/dl (95% CI: 3.63–6.00; p< 0.00001) with heterogeneity of 77%. The level of this lipoprotein was significantly higher in the patients than in the controls.

Figure 5.

Forest plot of random-effects model of serum very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) levels in psoriatic patients compared with healthy controls

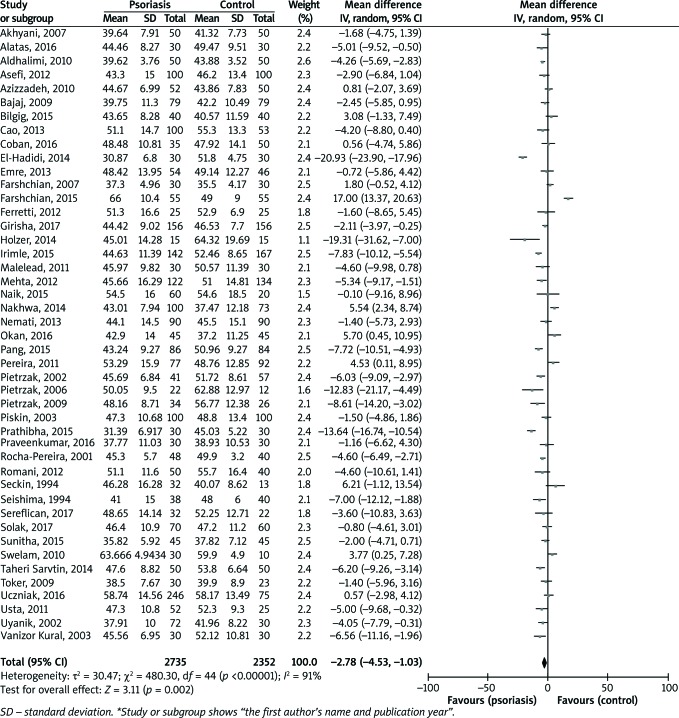

The results of serum HDL levels in the psoriatic patients compared with the controls are reported in Figure 6. The pooled MD was –2.78 mg/dl (95% CI: –4.53 – –1.03;p< 0.002). The level of this lipoprotein was significantly lower in the patients than in the controls (heterogeneity = 91%).

Figure 6.

Forest plot of random-effects model of serum high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels in psoriatic patients compared with healthy controls

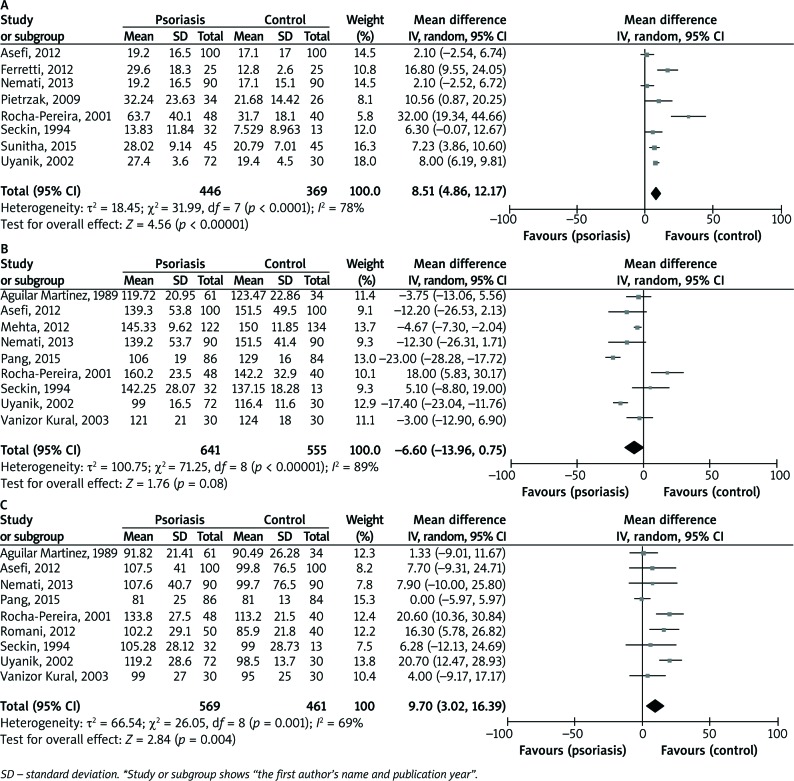

Apolipoprotein profiles

The studies reporting Lp(a) levels in the patients compared with controls showed that the pooled MD was 8.51 mg/dl (95% CI: 4.86–12.17; p< 0.0001), indicating that serum Lp(a) was significantly higher in the patients than in the controls (heterogeneity = 78%), (Figure 7 A). Figures 7 B and C show the results of Apo A1 and Apo B, respectively. The pooled MD of Apo A1 was –6.60 mg/dl (95% CI: –13.96 – 0.75; p< 0.08) and that of Apo B was 9.70 mg/dl (95% CI: 3.02–16.39; p< 0.004), and heterogeneities were 89% and 69%, respectively. Therefore, there was no significant difference between the patients and the controls in Apo A1, but Apo B level was significantly higher in the patients than in the controls.

Figure 7.

Forest plot of random-effects model of serum lipoprotein (a) or Lp(a) (A), Apolipoprotein A1 (B), and Apolipoprotein B (C) levels in psoriatic patients compared with healthy controls

Quality evaluation

Supplementary Table S2 shows the quality score for studies included in meta-analysis; indicating the mean quality score of 6.1 (medium quality). Nineteen studies had high quality (score ≥ 7).

Supplementary Table S2

Publication bias

Supplementary Figure S2 shows the funnel plot of studies included in each analysis. Begg’s and Egger’s tests did not reveal significant evidence of publication bias among the included studies in each subgroup.

Supplementary Figure S2

Discussion

This extensive meta-analysis evaluated the lipid and lipoprotein levels in psoriatic patients compared with healthy controls. The results showed that total cholesterol, TG, LDL, VLDL, Lp(a) and Apo B levels were significantly higher in patients, the HDL level was significantly lower in patients than controls, and the Apo A1 level was similar in two groups. It is still controversial whether changes in lipid composition are primary events or secondary to psoriasis, or perhaps due to medications such as cyclosporin and retinoids [16, 50].It is also still debated if activation of the immune system in psoriasis may cause some changes in patients’ lipid profile, hence in this category of subjects an acceleration of atherosclerosis processes in comparison with the general population has been shown [30, 33, 54].Additionally, psoriatic patients can be at increased CV risk, even after group matching on the basis of BMI [43, 48, 57]. Apo A1 has been advocated as a strong predictor of CV events, with potential advantages over HDL [33].

Apo A1 has protective effects against CV disease, whereas Apo B increases the CV risk [11].Some evidence showed that Apo B might be a better predictor for CV disease than LDL [3].The carriers of PON1 M allele have distinctly reduced ApoA1 levels, but have increased Lp(a) and Apo B levels. These findings indicate that this polymorphism may be involved in the development of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular diseases (CVD) in patients with psoriasis. In general terms, a strict relationship between psoriasis, lipoproteins and oxidative damage does exist [33].Cholesterol and LDL levels have been found to be higher in psoriasis, which could be related to the same pathogenesis of psoriasis and atherosclerosis [60].Another factor that could contribute to the atherosclerotic process and subsequent CV events is represented by the increased carotid mean intima-media thickness (IMT); and this is of great importance in neurological diseases, since it plays a strong role in ischemic cerebrovascular events (strictly related to CV diseases) [61].Increased IMT as well as a high prevalence of metabolic syndrome have been already reported in psoriatic patients [62–64].Moreover, metabolic syndrome is closely linked to bad life habits leading to overweight/obesity and inactivity; in this regard, lifestyle factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, sedentary lifestyle, and systemic psoriasis therapy may influence CV risk factors and may have a negative direct impact on these risk factors [26, 39, 47, 49, 64, 65].

Epidemiological studies have demonstrated that smoking is not only a risk factor for psoriasis, but it also increases the severity of psoriasis while lowering the response to treatments [66].Serum HDL levels were found to be significantly lower in the smoker patients than in non-smoker controls; whereas, the serum TG levels were significantly higher. There was no compelling difference among the non-smoker patients, both control groups, and smoker patients regarding serum lipids, and PASI levels were significantly higher in smoker patients than in non-smoker patients, as previously reported by Emre et al. [22].Therefore, HDL levels have protective properties against the CV risk [45].Smoking increased the psoriasis risk nearly two folds [42].Obesity is a known risk factor for psoriasis development and may be correlated with psoriasis activity. Psoriatic patients have a higher prevalence and incidence of obesity, and those with more severe skin lesions have higher odds of obesity than those with mild psoriasis [67].

In observational studies, it has also been reported that the risk of systolic hypertension was two times higher in psoriatic patients than in the general population, and more severe the development of psoriasis the higher the risk of hypertension [68].On the other hand, it has to be taken in account that some antihypertensive drugs can play a role in inducing psoriasis, and, among them, β-blockers and sartans (i.e. losartan) are the most famous ones [69].So, in case of patients suffering from hypertension, administration of certain category of drugs (β-blockers, sartan molecules) might be avoided. This fact could probably represent a bias in some studies. It can be concluded that psoriasis may be an independent risk factor for diseases such as ischemic heart disease, DM, hypertension, and obesity [32].Conversely, long-term hypertensive status is associated with an increased risk of psoriasis [46, 68].

Increased Lp(a) levels and modifications of biochemical markers of lipid peroxidation related to the severity of psoriasis could be involved in the pathogenesis and progression of the disease and related complications [55].Increased Lp(a) levels may also affect the expression of vascular adhesion protein 1 (VAP-1) or its activity in the adhesion and migration of T cells, thereby increasing the risk factor for psoriasis and its complications [11].Therefore, lifestyle, eating habits, smoking and alcohol are important components that increase the incidence and severity of psoriasis. Also, some systemic diseases such as high blood pressure, DM, etc. can be other risk factors for this disease. Overall, lipid and lipoprotein changes in psoriatic patients, compared with healthy subjects, can be primary or secondary factors involved in the development of the disease, which should be considered in the first visit or during the patients’ follow-up, thus even conditioning the choice of treatments.

There were several limitations in this meta-analysis. First of all, smoking and alcohol consumption had not been controlled in a lot of studies. Secondly, PASI score was different in the studies, although PASI score can easily change in the same patient during life (and not only in relation to treatment of psoriasis). Thirdly, in some studies the patients with psoriasis had metabolic syndrome, unless it is well-known that psoriasis is strictly associated to metabolic syndrome, thus leading to an increased risk of CV events (as stated above) [64].Fourthly, there was a high heterogeneity among analyses. But the strengths of this study were: 1) age, sex, and BMI had been matched in the most studies; and 2) there was no bias in the analyses.

Conclusions

This extensive meta-analysis showed abnormality of serum lipid, lipoprotein, and apolipoproteinlevels in psoriatic patients, compared with controls, and possibly a greater risk of atherosclerosis and CV accidents in the patients. Therefore,psoriatic patients should be risk-evaluated for CV accidents and atherosclerosis and should be carefully screened for lipid abnormalities, which can help in the early detection of lipid dysfunction and comorbidity of CV and atherosclerosis.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Irimie M, Oanţă A, Irimie CA, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis: a case-control study on the Brasov County population. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 2015; 23: 28-35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romaní J, Caixàs A, Carrascosa JM, et al. Effect of narrowband ultraviolet B therapy on inflammatory markers and body fat composition in moderate to severe psoriasis.Br J Dermatol 2012; 166: 1237-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nemati H, Khodarahmi R, Sadeghi M, et al. Antioxidant status in patients with psoriasis. Cell Biochem Funct 2014; 32: 268-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puig-Sanz L. Psoriasis, a systemic disease? Actas Dermosifiliogr 2007; 98: 396-402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myœliwiec H, Baran A, Harasim-Symbor E, et al. Serum fatty acid profile in psoriasis and its comorbidity. Arch Dermatol Res 2017; 309: 371-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krueger G, Ellis CN. Psoriasis recent advances in understanding its pathogenesis and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005; 53: S94-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA 2006; 296: 1735-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spuls PI, Lecluse LLA, Poulsen MNF, et al. How good are clinical severity and outcome measures for psoriasis: quantitative evaluation in a systematic review. J Invest Dermatol 2010; 130: 933-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deiana L, Pes GM, Carra C, et al. Lipid and lipoprotein profile in psoriasis. Boll Soc Hal Biol Sper 1992; 68: 755-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aguilar Martinez A, Guerra Rodriguez P, Ambrojo Antunez P, et al. Serum levels of apolipoproteins AI, AII and B in psoriasis. Dermatologica 1989; 179: 200-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nemati H, Khodarahmi R, Rahmani A, et al. Serum lipid profile in psoriatic patients: correlation between vascular adhesion protein 1 and lipoprotein (a). Cell Biochem Funct 2013; 31: 36-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of non-randomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2011. Available at: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. (last accessed 12 Jan 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol 2005; 5: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biau DJ. In brief: Standard deviation and standard error. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011; 469: 2661-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seckin D, Tokgözoğlu L, Akkaya S. Are lipoprotein profile and lipoprotein (a) levels altered in men with psoriasis? J Am Acad Dermatol 1994; 31: 445-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uyanik BS, Ari Z, Onur E, et al. Serum lipids and apolipoproteins in patients with psoriasis. Clin Chem Lab Med 2002; 40: 65-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piskin S, Gurkok F, Ekuklu G, Senol M. Serum lipid levels in psoriasis. Yonsei Med J 2003; 44: 24-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vanizor Kural B, Orem A, Cimşit G, et al. Plasma homocysteine and its relationships with atherothrombotic markers in psoriatic patients. Clin Chim Acta 2003; 332: 23-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toker A, Kadi M, Yildirim AK, et al. Serum lipid profile paraoxonase and arylesterase activities in psoriasis. Cell Biochem Funct 2009; 27: 176-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Usta M, Turan E, Aral H, et al. Serum paraoxonase-1 activities and oxidative status in patients with plaque-type psoriasis with/without metabolic syndrome. J Clin Lab Anal 2011; 25: 289-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emre S, Metin A, Demirseren DD, et al. The relationship between oxidative stress, smoking and the clinical severity of psoriasis.J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2013; 27: e370-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bilgiç R, Yıldız H, Abuaf OK, et al. Evaluation of serum asymmetric dimethylarginine levels in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Arch Turk Dermatol Venerol 2015; 49: 13-8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alatas ET, Kalayci M, Kara A, Dogan G. Association between insulin resistance and serum and salivary irisin levels in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Dermatologica Sinica 2017; 35: 12-5. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coban M, Tasli L, Turgut S, et al. Association of adipokines, insulin resistance, hypertension and dyslipidemia in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Ann Dermatol 2016; 28: 74-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okan G, Baki AM, Yorulmaz E, et al. Serum visfatin, fetuin-A, and pentraxin 3 levels in patients with psoriasis and their relation to disease severity. J Clin Lab Anal 2016; 30: 284-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sereflican B, Bugdayci G. Components of the alternative complement pathway in patients with psoriasis. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat 2017; 26: 37-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Solak B, Dikicier BS, Erdem T. The role of uric acid in metabolic syndrome in patients with psoriasis. Turk Arch Dermatol Venereol 2017; 51: 37-40. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farshchian M, Zamanian A, Farshchian M, et al. Serum lipid level in Iranian patients with psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2007; 21: 802-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akhyani M, Ehsani AH, Robati RM, Robati AM. The lipid profile in psoriasis: a controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2007; 21: 1330-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Azizzadeh M, Ghorbani R, Sharafi M. Serum lipids profiles in psoriatic patients. J Semnan Univ Med Sci 2010; 11: 307-11. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malekzad F, Robati R, Abaei H, et al. Insulin resistance in psoriasis: a case-control study. Iran J Dermatol 2011; 14: 136-9. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Asefi M, Vaisi-Raygani A, Bahrehmand F, et al. Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) 55 polymorphism, lipid profiles and psoriasis.Br J Dermatol 2012; 167: 1279-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taheri Sarvtin M, Hedayati MT, Shokohi T, Haj Heydari Z. Serum lipids and lipoproteins in patients with psoriasis. Arch Iran Med 2014; 17: 343-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farshchian M, Ansar A, Sobhan M. Associations between cardiovascular risk factors and psoriasis in Iran. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2015; 8: 437-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bajaj DR, Mahesar SM, Devrajani BR, Iqbal MP. Lipid profile in patients with psoriasis presenting at Liaquat University Hospital Hyderabad. J Pak Med Assoc 2009; 59: 512-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pereira RR, Amladi ST, Varthakavi PK. A study of the prevalence of diabetes, insulin resistance, lipid abnormalities, and cardiovascular risk factors in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. Indian J Dermatol 2011; 56: 520-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakhwa YC, Rashmi R, Basavaraj KH. Dyslipidemia in psoriasis: a case controlled study. Int Sch Res Notices 2014; 2014: 729157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prathibha K, Aliya Nusrath, Maithri CM. Assessment of inflammatory marker and dyslipidemias in psoriasis. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res 2015; 31: 228-31. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sunitha S, Rajappa M, Thappa DM, et al. Comprehensive lipid tetrad index, atherogenic index and lipid peroxidation: surrogate markers for increased cardiovascular risk in psoriasis.Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2015; 81: 464-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Praveenkumar U, Ganguly S, Ray L, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in psoriasis patients and its relation to disease duration: a hospital based case-control study. J Clin Diagn Res 2016; 10: WC01-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Girisha BS, Thomas N. Metabolic syndrome in psoriasis among urban South Indians: a case control study using SAM-NCEP criteria. J Clin Diagn Res 2017; 11: WC01-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pietrzak A, Lecewicz-Toruñ B. Activity of serum lipase [EC 3.1.1.3] and the diversity of serum lipid profile in psoriasis. Med Sci Monit 2002; 8: CR9-13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pietrzak A, Jastrzebska I, Krasowskaa D, et al. Serum pancreatic lipase [EC 3.1.1.3] activity, serum lipid profile and peripheral blood dendritic cell populations in normolipidemic males with psoriasis. J Mol Catal B Enzym 2006; 40: 144-54. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pietrzak A, Kadzielewski J, Janowski K, et al. Lipoprotein (a) in patients with psoriasis: associations with lipid profiles and disease severity. Int J Dermatol 2009; 48: 379-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uczniak S, Gerlicz ZA, Kozłowska M, Kaszuba A. Presence of selected metabolic syndrome components in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Adv Dermatol Allergol 2016; 33: 114-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mehta NN, Li R, Krishnamoorthy P, et al. Abnormal lipoprotein particles and cholesterol efflux capacity in patients with psoriasis. Atherosclerosis 2012; 224: 218-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cao LY, Soler DC, Debanne SM, et al. Psoriasis and cardiovascular risk factors: increased serum myeloperoxidase and corresponding immunocellular overexpression by Cd11b(+) CD68(+) macrophages in skin lesions. Am J Transl Res 2013; 6: 16-27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Naik HB, Natarajan B, Stansky E, et al. Severity of psoriasis associates with aortic vascular inflammation detected by FDG PET/CT and neutrophil activation in a prospective observational study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2015; 35: 2667-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seishima M, Seishima M, Mori S, Noma A. Serum lipid and apolipoprotein levels in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 1994; 130: 738-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takeda H, Okubo Y, Koga M, Aizawa K. Lipid analysis of peripheral blood monocytes in psoriatic patients using Fourier-transform infrared microspectroscopy. J Dermatol 2001; 28: 303-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Swelam MM, Ahmed MM, Allah Ahmed NA, et al. The lipid profile in psoriatic patients. AAMJ 2010; 8: 284-91. [Google Scholar]

- 53.El-Hadidi H, Samir N, Shaker OG, Otb S. Estimation of tissue and serum lipocalin-2 in psoriasis vulgaris and its relation to metabolic syndrome. Arch Dermatol Res 2014; 306: 239-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Antonucci VA, Tengattini V, Balestri R, et al. Intima-media thickness in an Italian psoriatic population: correlation with lipidic serum levels, PASI and BMI. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014; 28: 512-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ferretti G, Bacchetti T, Campanati A, et al. Correlation between lipoprotein(a) and lipid peroxidation in psoriasis: role of the enzyme paraoxonase-1. Br J Dermatol 2012; 166: 204-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Holzer M, Wolf P, Inzinger M, et al. Anti-psoriatic therapy recovers high-density lipoprotein composition and function. J Invest Dermatol 2014; 134: 635-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rocha-Pereira P, Santos-Silva A, Rebelo I, et al. Dislipidemia and oxidative stress in mild and in severe psoriasis as a risk for cardiovascular disease. Clin Chim Acta 2001; 303: 33-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aldhalimi MA, Almuhanna SJ, Alrikabi SH. Serum lipid level in Iraqi patients with psoriasis. Skinmed 2010; 8: 204-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pang X, Lin K, Liu W, et al. Characterization of the abnormal lipid profile in Chinese patients with psoriasis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2015; 8: 15280-4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Frostegard J, Ulfgren AK, Nyberg P, et al. Cytokine expression in advanced human atherosclerotic plaques: dominance of pro-inflammatory (Th1) and macrophage stimulating cytokines. Atherosclerosis 1999; 145: 33-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Prati P, Vanuzzo D, Casaroli M, et al. Determinants of carotid plaque occurrence. A long-term prospective population study: the San Daniele Project. Cerebrovasc Dis 2006; 22: 416-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Troitzsch P, Paulista Markus MR, Dörr M, et al. Psoriasis is associated with increased intima-media thickness--the Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP). Atherosclerosis 2012; 225: 486-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kothiwala SK, Khanna N, Tandon N, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular changes in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis and their correlation with disease severity: a hospital-based cross-sectional study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2016; 82: 510-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rodríguez-Zúñiga MJM, García-Perdomo HA. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between psoriasis and metabolic syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017; 77: 657-66.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Naldi L, Chatenoud L, Linder D, et al. Cigarette smoking, body mass index, and stressful life events as risk factors for psoriasis: results from an Italian case-control study. J Invest Dermatol 2005; 125: 61-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Armstrong AW, Armstrong EJ, Fuller EN, et al. Smoking and pathogenesis of psoriasis: a review of oxidative, inflammatory and genetic mechanisms. Br J Dermatol 2011; 165: 1162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ. The association between psoriasis and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Diabetes 2012; 2: e54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gottlieb AB, Dann F. Comorbidities in patients with psoriasis. Am J Med 2009; 122: 1150.e1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Balak DM, Hajdarbegovic E. Drug-inducedpsoriasis: clinicalperspectives. Psoriasis (Auckl) 2017; 7: 87-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1

Supplementary Figure S1

Supplementary Table S2

Supplementary Figure S2