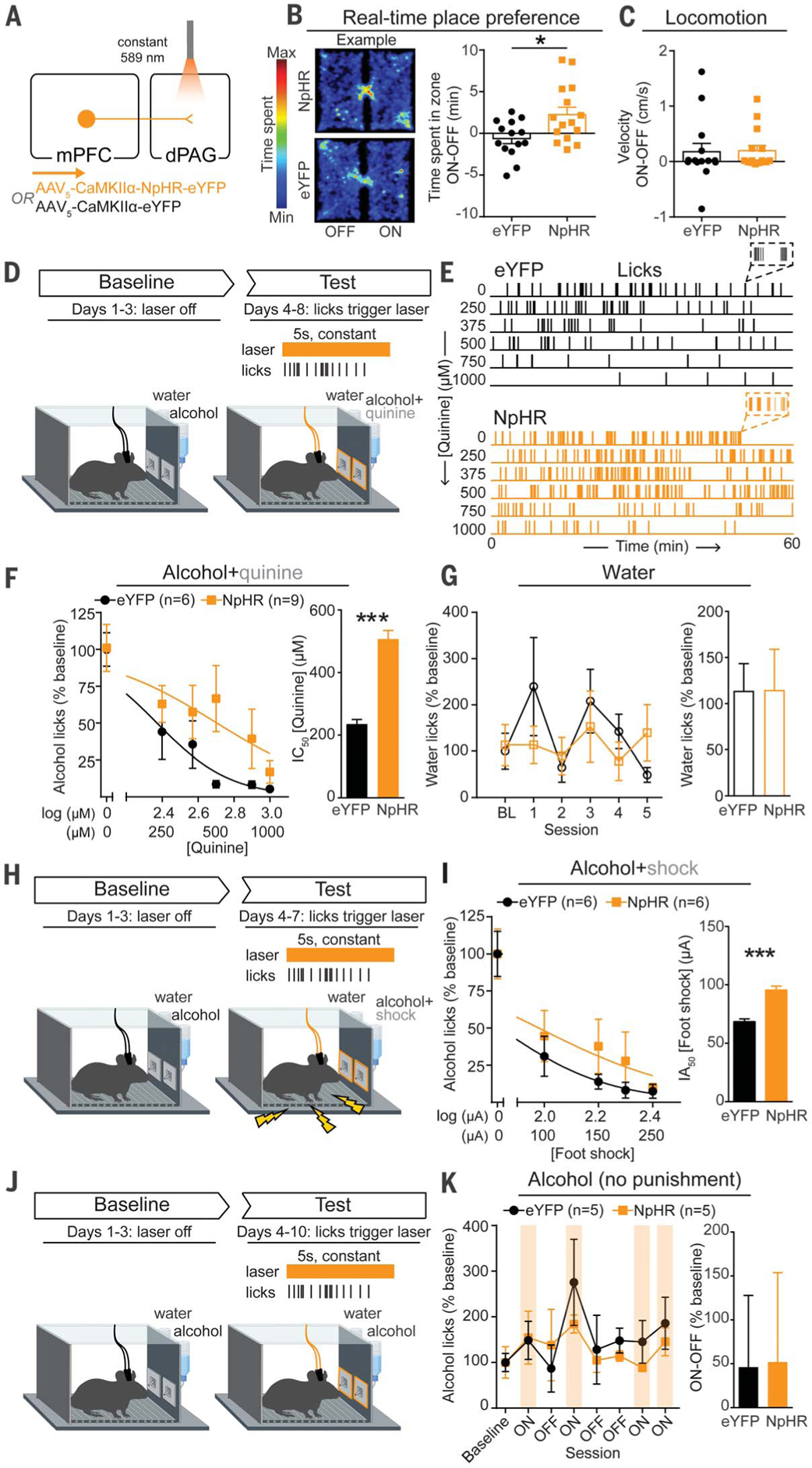

Fig. 3. Inhibition of mPFC-dPAG neurons drives compulsive drinking but does not alter drinking in the absence of punishment.

(A) Strategy to inhibit mPFC terminals in the dPAG. (B) Inhibition of mPFC terminals in the dPAG was preferred in a real-time place preference task (unpaired t test, t(27) = 2.647, *p = 0.013). (C) Photoinhibition did not alter locomotion (unpaired t test, t(27) = 0.1191, p = 0.91). (D) On test days, water or alcohol spout contacts triggered a photoinhibition period. During the test, the quinine concentration was increased across days (alcohol bottle only). (E) Example alcohol lick event records. (F) The concentration of quinine required to decrease alcohol spout licking to 50% of baseline (IC50) was greater in NpHR animals (unpaired t test, t(13) =22.05, ***p < 0.0001). (G) No difference in licking for water between groups (unpaired t test, t(13) = 0.016, p = 0.99). (H) Alcohol drinking punished with foot shock. (I) Foot-shock amplitude required to attenuate alcohol spout licks by 50% of baseline [half-maximal inhibitory amplitude (IA50)] was increased in NpHR animals (unpaired t test, t(10) = 6.498, ***p < 0.0001). (J) Alcohol drinking in the absence of punishment. (K) Photoinhibition did not alter licking for alcohol in the absence of punishment (unpaired t test, t(8) = 0.045, p = 0.97). Error bars indicate ± SEM.