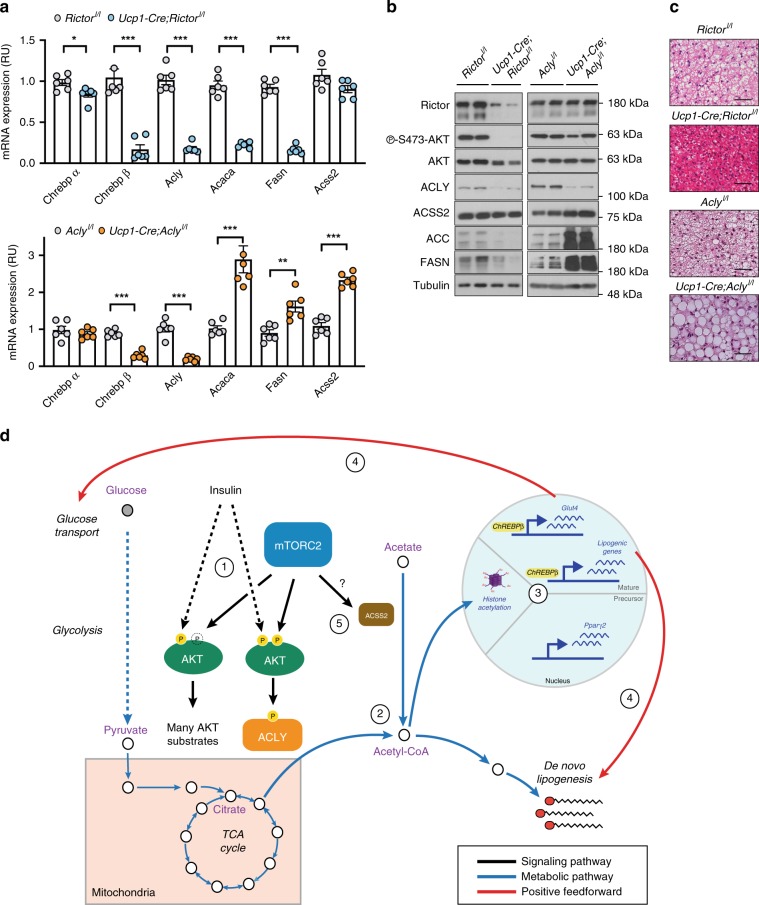

Fig. 7. In vivo, mTORC2 and ACLY both promote ChREBPβ expression, but their loss has opposite effects on ACC and FASN expression that correlates with differential ACSS2 regulation.

a qRT-PCR analysis of the indicated genes in brown fat tissue isolated from control (Rictorl/l and Aclyl/l) or UCP1-Cre-Rictorl/l and UCP1-Cre-Aclyl/l mice (n = 6 per group). Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001. Statistical significance was calculated by using two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s test multiple comparisons (a). b Corresponding western blots for a. Black arrows indicate the ACC1 and ACC2 isoforms. c Hematoxylin and eosin stains showing brown fat morphology for the indicated genotypes. Scale bar represents 200 μm. d Our results support the following model of mTORC2 action in brown adipocytes: (1) mTORC2-dependent AKT phosphorylation is distinctly important for ACLY phosphorylation, while for many other AKT substrates, mTORC2 may normally facilitate their phosphorylation, but it is dispensable (indicated by “P” within an unshaded broken circle). This is indicated by the fact that phosphorylation of many AKT substrates is unimpaired by Rictor deletion while ACLY phosphorylation is reduced. (2) mTORC2/AKT-dependent ACLY phosphorylation promotes acetyl-CoA synthesis and primes de novo lipogenesis downstream of glucose uptake and glycolysis. (3) The increased flux to acetyl-CoA additionally stimulates histone acetylation. In brown adipocyte precursors, this coincides with pparγ induction to drive differentiation; in mature brown adipocytes, this coincides with ChREBPβ activity to increase expression of gluco-lipogenic genes. (4) Gluco-lipogenic gene expression then provides a positive feedback effect on glucose transport and de novo lipogenesis. (5) mTORC2 may also stimulate acetate metabolism to acetyl-CoA by regulating the expression and/or activity of ACSS2. Notably, from these data we cannot distinguish between cytoplasmic and nuclear pools of acetyl-CoA.