Abstract

This cohort study uses commercial insurance data to examine the association between rotavirus vaccination and type 1 diabetes incidence.

Rotavirus may precipitate type 1 diabetes (T1D).1,2 Thus, rotavirus vaccination may be associated with T1D. For example, incidence of T1D in Australian children younger than 5 years declined after rotavirus vaccine introduction.3 However, 2 Finnish studies4,5 showed no association of rotavirus vaccination with T1D risk in children 10 years and younger, although statistical power in these studies was limited. We compared T1D risk by rotavirus vaccination status among US children with commercial insurance.

Methods

Data for January 2006 through December 2017 were analyzed from the IBM MarketScan Commercial Database (formerly known as the Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database), which contains deidentified data from more than 20 million individuals in employer-sponsored commercial health insurance plans. Because all data were fully deidentified and no interaction occurred with humans, this analysis was deemed exempt from review and informed consent by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention institutional review board.

Children were included if they were age eligible to receive rotavirus vaccine (with a birthdate of January 1, 2006, or later) and continuously enrolled in their insurance plan from birth. Current Procedural Terminology codes (90680 [for RotaTeq vaccine (Merck Sharp & Dohme Corporation)] and 90681 [for Rotarix vaccine (GlaxoSmithKline)]) were used to determine rotavirus vaccination status and age at each dose, as previously described.6 To increase specificity, T1D was defined as 2 or more separate claims listing International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes 250.X1 or 250.X3 or International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes E10.X in any care setting. Children with a single T1D claim were excluded, as were those diagnosed those diagnosed before 27 weeks of age (survival curve) or before 12 months of age (measures of association).

For the survival curve, follow-up began at 27 weeks of age. For measures of association, follow-up began at 12 months of age. Crude rate ratios were calculated using person-time accumulated in each stratum of rotavirus vaccination status. Extended Cox regression models with age in weeks as the time scale included rotavirus vaccination status as the time-varying exposure and were controlled for birth year. To mitigate exposure misclassification from missing vaccination claims and control for confounding by medical conditions possibly associated with missed vaccinations and risk of T1D, only children who received at least 1 dose of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis–containing vaccine were included. This restriction was lifted in a sensitivity analysis. In a second sensitivity analysis, children in states with universal vaccine purchase programs were excluded, since they could have been vaccinated without a vaccination-associated insurance claim. Results were stratified by birth year, since loss to follow-up increased with increasing age. Data were censored at the end of continuous enrollment, the end of the study period (December 31, 2017), or diagnosis of T1D, whichever came first.

Analyses used SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute) and R version 3.4.2 (the R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Data analysis occurred from January 2019 to April 2019; α was set to .05.

Results

Overall, 843 of 2 854 571 eligible children were diagnosed with T1D; the 10-year cumulative incidence was 0.25% (95% CI, 0.22%-0.28%). Among 1 563 540 children followed up until age 12 months or older, 1 035 198 (66.2%) were fully vaccinated (2 doses of Rotarix or 3 doses of RotaTeq), 210 057 (13.4%) were partially vaccinated, and 318 285 (20.4%) were unvaccinated against rotavirus.

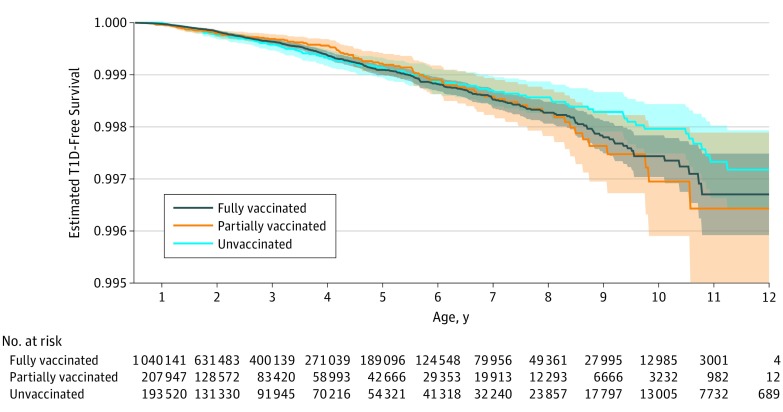

Unadjusted T1D-free survival curves were stratified by rotavirus vaccination status (Figure). Adjusted hazard ratios comparing fully and partially vaccinated children with unvaccinated children were nonsignificant in primary and sensitivity analyses (Table).

Figure. Unadjusted Type 1 Diabetes (T1D)–Free Survival Curve, by Rotavirus Vaccination Status.

Type 1 diabetes–free survival curve confidence intervals overlapped among children fully vaccinated (gray) compared with children partially vaccinated (orange) or unvaccinated (blue) against rotavirus. The plot is shown beginning at age 27 weeks, by which time all children will have been eligible to be fully vaccinated against rotavirus. Children who had not yet received any doses of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis–containing vaccines are excluded, as were those receiving a T1D diagnosis or lost to follow-up before 27 weeks. Rotavirus vaccination status is treated as time varying. Data are from the IBM MarketScan Commercial Database (formerly known as the Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database), 2006 through 2017.

Table. Number of Children, Length of Follow-up, and Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) Rates by Rotavirus Vaccination Statusa.

| Group | Children, No. (%) | Follow-up, y | No. Who Developed T1D | Rate/100 000 Person-Years | Crude Rate Ratio | Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI)c | Sensitivity Analysis, Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD)b | Median (Interquartile Range)b | Sum | 1d | 2e | ||||||

| Completed vaccination series | 1 035 198 (66) | 2.2 (2.2) | 1.5 (0.6-3.2) | 2 297 088 | 492 | 21.4 | 1.01 | 1.09 (0.87-1.36) | 1.14 (0.95-1.38) | 1.22 (0.96-1.55) |

| Partially vaccinated | 210 057 (13) | 2.4 (2.3) | 1.5 (0.6-3.5) | 497 374 | 100 | 20.1 | 0.95 | 1.03 (0.78-1.36) | 1.05 (0.82-1.35) | 1.18 (0.88-1.58) |

| Not vaccinated | 318 285 (20) | 2.9 (2.8) | 1.8 (0.7-4.3) | 909 692 | 192 | 21.1 | 1.00 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

Including only children surviving to at least 12 months with continuous enrollment and without any T1D claims before that time, excluding 22 patients with T1D diagnosed before 2 months of age, 59 patients diagnosed between 2 and 12 months of age, and 283 children with only a single claim for T1D. Also excludes 1 290 972 children whose continuous enrollment lapsed before 12 months of age.

Numbers after the 1 year of compulsory follow-up (ie, total follow-up is this number plus 1 year).

Adjusted for year of birth and excluding 138 751 children who had never received any doses of tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis–containing vaccines; 95% CIs generated using robust standard errors.

Adjusted for year of birth and including all children followed up until at least 12 months of age with continuous enrollment and without any T1D claims before that time, without restrictions based on receipt of tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis–containing vaccines.

Adjusted for year of birth and excluding 138 751 children who had never received any doses of tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis–containing vaccines as well as an additional 92 616 children born into states with universal vaccine purchase programs (2006-2012: Alaska, Idaho, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington, Wisconsin, and Wyoming; 2013-2014: Connecticut, Idaho, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Vermont, Washington, and Wyoming; and 2015-2017: Alaska, Connecticut, Idaho, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington, and Wyoming).

Discussion

We found no association between rotavirus vaccination and T1D among US children with commercial insurance who were followed up until a maximum of 12 years of age. This is consistent with results from 2 Finnish cohorts.4,5

Some limitations should be considered. First, the MarketScan database, although comprehensive, is not nationally representative. Second, neither vaccination nor T1D were confirmed by medical record review, and 138 751 children (those with no recorded diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis doses; 8.2% of 1 702 291 children who would otherwise have been eligible based on date of birth, length of follow-up, and continuous enrollment) were excluded. However, sensitivity analyses suggest that vaccine status misclassification had minimal association with outcomes, and ICD-9-CM codes have a strong association with T1D among children. Last, loss to follow-up is substantial, especially after 5 years, and this contributed to wide 95% CIs. However, sensitivity analyses indicated similar conclusions by birth cohort.

Our results are consistent with a favorable safety profile for rotavirus vaccines. They support continued universal rotavirus vaccination in the United States.

References

- 1.Blomqvist M, Juhela S, Erkkila S, et al. . Rotavirus infections and development of diabetes-associated autoantibodies during the first 2 years of life. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;128(3):511-515. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01842.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Honeyman MC, Coulson BS, Stone NL, et al. . Association between rotavirus infection and pancreatic islet autoimmunity in children at risk of developing type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2000;49(8):1319-1324. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.8.1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perrett KP, Jachno K, Nolan TM, Harrison LC. Association of rotavirus vaccination with the incidence of type 1 diabetes in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(3):280-282. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaarala O, Jokinen J, Lahdenkari M, Leino T. Rotavirus vaccination and the risk of celiac disease or type 1 diabetes in Finnish children at early life. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;36(7):674-675. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hemming-Harlo M, Lähdeaho ML, Mäki M, Vesikari T. Rotavirus vaccination does not increase type 1 diabetes and may decrease celiac disease in children and adolescents. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019;38(5):539-541. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burke RM, Tate JE, Dahl RM, Aliabadi N, Parashar UD. Rotavirus vaccination is associated with reduced seizure hospitalization risk among commercially insured U.S. children. Clin Infect Dis. 2018. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]