Abstract

Phosphorus (P) is an essential macronutrient for plant growth and development. The concentration of flavonol, a natural plant antioxidant, is closely related to phosphorus nutritional status. However, the regulatory networks of flavonol biosynthesis under low Pi stress are still unclear. In this study, we identified a PFG-type MYB gene, NtMYB12, whose expression was significantly up-regulated under low Pi conditions. Overexpression of NtMYB12 dramatically increased flavonol concentration and the expression of certain flavonol biosynthetic genes (NtCHS, NtCHI, and NtFLS) in transgenic tobacco. Moreover, overexpression of NtMYB12 also increased the total P concentration and enhanced tobacco tolerance of low Pi stress by increasing the expression of Pht1-family genes (NtPT1 and NtPT2). We further demonstrated that NtCHS-overexpressing plants and NtPT2-overexpressing plants also had increased flavonol and P accumulation and higher tolerance to low Pi stress, showing a similar phenotype to NtMYB12-overexpressing transgenic tobacco under low Pi stress. These results suggested that tobacco NtMYB12 acts as a phosphorus starvation response enhancement factor and regulates NtCHS and NtPT2 expression, which results in increased flavonol and P accumulation and enhances tolerance to low Pi stress.

Keywords: NtMYB12, low Pi stress, flavonol biosynthesis, overexpression, Nicotiana tabacum

Introduction

Flavonoids are a large group of secondary metabolites in plants, generally having a C6-C3-C6 carbon skeleton (Halbwirth, 2010; Li et al., 2015). The most common flavonoids found in plants are anthocyanin and flavonols (Holton and Edwina, 1995; Jia et al., 2015). Although various flavonol biofunctions in plants have been recognized, antioxidant capacity is a common feature for flavonols and most other flavonoid compounds (Nijveldt et al., 2001; Kuhn et al., 2011). Previous reports have shown that flavonols play important roles in various biological processes in plants, such as resistance to UV-B damage, cell-wall formation, and defense against pathogens, implying that flavonols play a key role in plant biofunction under stress conditions (Winkel, 2001; Khan et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2014; Martinez et al., 2016).

Flavonoid biosynthesis has been well documented in Arabidopsis, tomato, and woody plants (Holton and Edwina, 1995; Niggeweg et al., 2004; Li et al., 2015; Zhai et al., 2016; Zhai et al., 2019). Chalcone synthase (CHS), chalcone isomerase (CHI), flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H), flavonol synthase (FLS), and dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (DFR) catalyze the biosynthetic steps that convert phenylpropanoid precursors to flavonols and anthocyanin. Some MYB transcriptional factors (TFs) have been shown to directly regulate the biosynthesis of flavonoids (Dubos et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2013; Li, 2014; Liu et al., 2015; Zhai et al., 2016; Zhai et al., 2019). MYB75, MYB90, MYB113, and MYB114 are products of anthocyanin pigment (PAP)-type MYBs and are reported to regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis (Borevitz et al., 2000; Nesi et al., 2001; Gonzalez et al., 2008). MYB11, MYB12, MYB111, and HY5 are reported to regulate flavonol biosynthesis in Arabidopsis (Mehrtens et al., 2005; Stracke et al., 2010). Recently, Zhai et al. found that two MYB genes, PbMYB9 and PbMYB12, which are among the products of the flavonol glycoside (PFG)-type MYB TF family, are positive regulators of the flavonol biosynthesis pathway in pears (Pyrus bretschneideri Rehd.) and work by activating the expression of genes encoding CHS and FLS (Zhai et al., 2016; Zhai et al., 2019). Although the functions and regulatory mechanisms of plant MYB genes have been widely studied, more research is needed to understand the biological role of each member of this vast TF family.

Inorganic phosphorus (Pi) is an essential macronutrient for plant growth and development. It has not only a structural role in DNA, RNA, ATP, and phospholipids, but also an important regulatory role in several physiological processes, including photosynthesis, respiration, signal transduction, and energy metabolism (Marschner, 1995; Vance et al., 2003). P is typically absorbed by Pi transporters (PTs) and assimilated into plant cells and tissues in its inorganic form (Pi) (Marschner, 1995). Genes codifying these Pi transporters are generally classified into four families (Pht1 to Pht4), which suggests their diverse biological functions for plant growth and development (Jia et al., 2011; Song et al., 2017; Chang et al., 2019). The Pht1 family belongs to the high-affinity PTs, whose expression is up-regulated distinctly under low Pi stress conditions, playing a crucial role in both Pi uptake and translocation under Pi deficiency.

Pi deficiency impairs the biosynthesis of macromolecules and various other biological processes, which may result in serious cellular damage and growth retardation (Chang et al., 2019). Plants respond to environmental Pi deficiency by altering their developmental and metabolic programs to better survive and grow under nutritional stress (Franco-Zorrilla et al., 2004; Chiou and Lin, 2011; Lynch, 2011; Smith et al., 2011; Jain et al., 2012; Jia et al., 2017; Pan et al., 2019). Typically, numerous genes are activated (e.g., high-affinity Pi transporters), plant root architecture is changed, anthocyanin is accumulated, and antioxidant capacity is enhanced. Previously, we found that Pi deficiency prompts tobacco plants to accumulate flavonols, implying that there is an interaction between phosphorus nutrition and flavonol metabolism (Jia et al., 2015). However, the molecular process underlying this response is still unclear.

Tobacco is a major cash crop worldwide and has abundant flavonoids in its leaves. For this reason, tobacco is the proper model plant in which to explore the function of flavonoid biosynthetic genes in low Pi tolerance. In our previous study, the transcriptome databases were analyzed for low N, low Pi, and low K stress conditions in tobacco. The results showed that NtMYB12 expression was induced in the transcriptome database under the Pi-deficient condition, implying that NtMYB12 may play a key role in the Pi signaling pathway. In this study, we comprehensively investigated the effects of the tobacco gene NtMYB12 on flavonol biosynthesis and plant growth and development under low Pi stress. Our results showed that NtMYB12 is a PFG-type MYB transcription factor that may be involved in the Pi signaling pathway. Overexpression of this gene enhances tolerance of low Pi stress by increasing flavonol and P accumulation in tobacco. These data demonstrate that NtMYB12 plays a critical role in the flavonol-synthesis pathway under low Pi stress conditions.

Material and Methods

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

NtMYB12-overexpression (T3 generation), NtCHS-overexpression (T2 generation), and NtPT2-overexpression (T3 generation) transgenic (named 35S:NtMYB12, 35S:NtCHS and 35S:NtPT2) and wild-type (Nicotiana tabacum cv, Yunyan 87) tobacco plants were used in this study. Samples of 150 tobacco seeds of transgenic plants and WT were sterilized with a solution of 75% (v/v) ethanol for 30 s and 10% (v/v) sodium hypochlorite for 10 min then washed six times with sterile distilled water and transferred to seedling trays (3 days). The trays were kept in a culture room in a dark environment of 28℃ for proper germination. The germinated seedlings were placed in a light incubator (RXZ-600, Ningbo Jiangnan Instrument Factory, China) with a day/night temperature of 28℃/23℃ and a 14-h-light/10-h-dark photoperiod. The relative humidity was approximately 60%, and the light intensity was controlled to 300 μmol·m-2·s-1 for 7 days. Sixteen tobacco seedlings were grown in each culture vessel (depth: 5 cm; diameter: 15 cm) with sand, and the Hoagland's nutrient solution was changed every day in the growth chamber (described above). Quarter-strength Hoagland's nutrient solution was used to culture the seedlings in the first 3 days, and half-strength nutrient solution was used in the second 3 days. Full-strength Hoagland's solution with high Pi (HP; 1mM Pi) or low Pi (LP; 0.02mM Pi) was then supplied to culture the seedlings for 21 days. Afterward, the tobacco seedlings were harvested for further analysis. (1) The phenotype of the tobacco seedlings was observed and recorded. (2) Some of the leaves were used for NBT staining. (3) The enzyme activity and MDA concentration of the seedlings were measured. (4) Some tobacco seedlings were used to detect the flavonol concentration, Pi concentration, and gene expression. (5) The other tobacco seedlings were oven-dried and used to measure the total P concentration.

Isolation and Sequence Analysis of NtMYB12

The full-length entire coding sequences (CDS) of NtMYB12 (GenBank accession: XM_016624824) and promoter from tobacco “Yunyan 87” were cloned using specific primers. The primers were designed based on the published sequence data in the tobacco Genome Database (Table S1). Cis elements in the promoters were identified via PlantCare (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/). Sequences of multiple peptides were aligned with DNAMAN software (Lynnon Biosoft, United States). A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Neighbor-Joining (NJ) algorithm in MEGA7.0 software (Kumar et al., 2008).

Sub-Cellular Localization of NtMYB12

For the analysis of subcellular localization, the entire coding sequence (CDS) of NtMYB12 was amplified and used to construct an N-terminus green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion vector, pMDC43-NtMYB12. The construct was transiently introduced into tobacco epidermal cells by injection, and the same transformation was carried out with P35S::GFP for control cells. After transformation, the tobacco epidermis samples were kept in a dark environment (25℃/16h). GFP fluorescence was observed using a confocal laser scanning microscope (Nikon C2-ER).

Generation of Transgenic Plants

For the preparation of cassettes for the overexpression of NtMYB12, NtCHS, and NtPT2, each gene was amplified and synthesized from tobacco leaf cDNA as follows. To construct the overexpression vector NtMYB12- pCAMBIA1305, the entire coding sequence (CDS) of NtMYB12 was amplified using primers (Table S1). The PCR product was digested with SacI/KpnI and cloned into the SacI/KpnI-digested pCAMBIA1305 plasmid under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter. In order to construct the overexpression vector NtCHS-pCAMBIA1305, the coding region (CDS) of NtCHS (Chen et al., 2017) was amplified using primers (Table S1). The PCR product was digested with SacI/KpnI and cloned into the SacI/KpnI-digested pCAMBIA1305 plasmid under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter. To construct the overexpression vector NtPT2-pCAMBIA1305, the coding region (CDS) of NtPT2 (Jia et al., 2018) was amplified using primers (Table S1). The PCR product was digested with SacI/XhoI and cloned into the SacI/XhoI-digested NtPT2-pCAMBIA1305 plasmid under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter. All of the constructs were transferred to Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105 by electroporation and then transformed into tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum cv, Yunyan 87) as described previously (Chen et al., 2011; Jia et al., 2018).

Southern Blotting Analysis

The independent 35S:NtMYB12 transgenic tobacco lines were identified by Southern blotting analysis. Genomic DNA was extracted from the leaves of wild-type (WT) and T1 transgenic plants by the SDS method, and 5 μg was digested with the restriction enzyme SacI overnight at 37°C. The digested DNA was separated on a 0.8% (w/v) agarose gel and then transferred to a Hybond-N+ nylon membrane and hybridized with the coding sequence of the hygromycin-resistance gene, which was used as the hybridization probe, as described previously (Zhou et al., 2008; Jia et al.,2017).

Determination of Flavonoid Compounds

The major flavonols were extracted from the leaves of tobacco samples (0.2 mg) using 2 ml of 100% methanol from Sigma (http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/) (fresh-weight basis). The flavonols were detected by HPLC (high-performance liquid chromatography, Agilent Technologies 1200 series) with a column (Agilent Technologies ZORBAX SB-C18 4.6 mm × 250 mm) and quantified by comparing the area of each individual peak with the curves obtained for the individual compounds (Li et al.,2015).

This was equilibrated with solvent A (water/acetonitrile/formic acid, 87:3:10) and solvent B (water/acetonitrile/formic acid, 40:50:10), eluting with a gradient of increasing solvent B at a flow rate 1ml·min-1. The gradient conditions were: time 0, 96% A, 4% B; 20 min, 80% A, 20% B; 35 min, 60% A, 40% B; 40 min, 40% A, 60% B; 45 min, 10% A, 90% B; 55 min, 96% A, 4% B. Detection by ultraviolet (UV) chromatograms was recorded at 325 nm. All of the flavonol standards, rutin, and kaempferolrutinoside were obtained from either Sigma-Aldrich or Extrasynthèse (Genay, France).

Determination of Total Anthocyanin Concentration

Total anthocyanin was extracted from fresh leaves of tobacco plants in 1% HCl in methanol with gentle shaking in the dark at 4℃ overnight. The extracts were diluted with an equal volume of water. An equal volume of chloroform was then added to the extracts, and the samples were vortexed slowly for a few seconds. The supernatant aqueous/methanol phase was obtained by centrifugation at 12,000g for 10 min. The absorbance of the supernatant at 530 nm was recorded in order to calculate the concentration of anthocyanin (Bariola et al., 1999; Li et al., 2014). Five repeats were conducted for each of three biological replicates. The values were normalized to the fresh weight of each sample.

RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis, and RT-qPCR

Total RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis were carried out using the method described by Jia et al. (2018). Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) analysis was performed using gene-specific primers for flavonol synthesis-related genes and Pht1 family genes in tobacco. The primers used for qRT-PCR are listed in Table S1. Relative transcript levels were normalized to that of NtL25 (L18908.1) and presented as 2-ΔΔCt (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

Biochemical Staining and Physiological Measurements

Superoxide (O2-) staining was performed by infiltration by the nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) method (Liu et al., 2018; Song et al., 2019). SOD and CAT activities were measured as described previously (Wang et al., 2012). The MDA concentration was determined with the thiobarbituric acid (TBA) method (Luo et al., 2019).

Measurement of Total P and Soluble Pi Concentration in Tobacco

About 0.05 g of dry ground powder of each sample was used for the measurement of total P concentration in the plants by the method described previously (Jia et al., 2015; Jia et al., 2018). About 0.5 g of fresh samples were used for the measurement of soluble Pi concentration in the plants by the method described previously (Zhou et al., 2008).

Statistical Analysis

All data were statistically analyzed by two-way ANOVA analysis and Tukey's multi-comparisons test (P < 0.05) in SAS software version 8.1. The results were expressed as the means and the corresponding standard errors.

Results

Identification and Molecular Characterization of NtMYB12

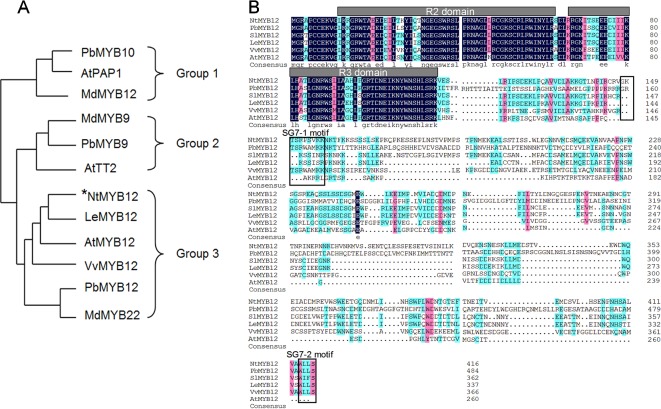

To determine the function of NtMYB12, the full-length coding sequence (CDS) of NtMYB12 was cloned from tobacco. The length of the protein encoded by NtMYB12 was 417 amino acids. Evolutionary study of the MYB gene family indicates that typical MYB transcription factors (TFs) involved in flavonoid biosynthesis can be classified into three different groups: PAP-type MYB TFs (group I, anthocyanin regulators), TT2-type MYB TFs (group II, flavanol regulators), and PFG-type MYB TFs (group III, flavonol regulators). Notably, NtMYB12 clusters with the PFG-type MYB TFs in group III (Figure 1A). Protein sequence alignment analysis showed that NtMYB12 contains two characteristic motifs, SG7-1 and SG7-2, commonly found in PFG-type MYB TFs (Figure 1B). Thus, NtMYB12 was identified as a typical PFG-type MYB TF, suggesting that NtMYB12 may be involved in the regulation of flavonol biosynthesis in tobacco.

Figure1.

Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis of NtMYB12. (A) Phylogenetic analysis of typical flavonoid-regulating MYBs from different species. These MYBs were classified into three major groups. The MYB protein sequences in other species were obtained from the NCBI database. Their protein accessions in the NCBI database are as follows: pear PbMYB10 (ALU57825.1), Arabidopsis PAP1 (AEE33419.1), apple MdMYB12 (ADL36755.1), apple MdMYB9 (ABB84757.1), pear PbMYB9 (ALU57827.1), Arabidopsis TT2 (OAO91653.1), Arabidopsis MYB12 (ABB03913), grapevine VvMYB12 (XP_002269995), PbMYB12 (ALF95174.1), and apple MdMYB22 (AAZ20438.1). The phylogenetic tree was constructed by MEGA7.0 using a bootstrap test of phylogeny with the Neighbor-Joining test and default parameters. (B) Protein sequence alignments of PFG-type MYBs from different species. The conserved R2 and R3 domains are underlined. Previously described SG7–1 and SG7–2 motifs are boxed. The multiple alignments were performed using DNAMAN 6.0.

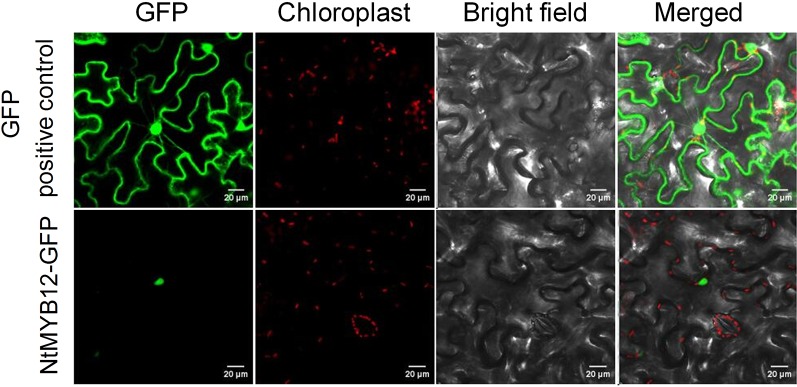

Subcellular Localization of NtMYB12

Plant MYB family members were predicted to be localized in the nucleoplasm. To verify NtMYB12 subcellular localization, we constructed N-terminal GFP fusions driven by the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter and transfected the derived expression vector into tobacco epidermal cells. As expected, microscopic observations demonstrated that the fused protein (NtMYB12-GFP) was restricted to the nucleoplasm, whereas, in control transgenic cells expressing p35S::GFP, the GFP signal was detected throughout all the cell (Figure 2), suggesting that NtMYB12 may work as a transcription factor.

Figure 2.

Sub-cellular localization of NtMYB12 in tobacco epidermal cells. The fusion protein (NtMYB12-GFP) and GFP-positive control were independently transiently expressed in tobacco cells. GFP fluorescence was observed with a fluorescence microscope.

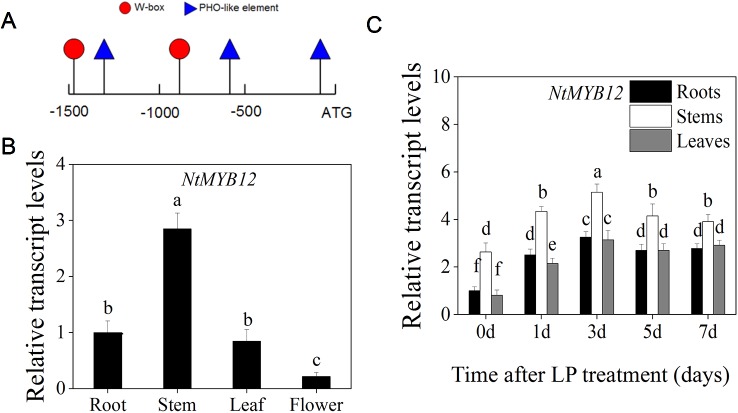

Expression of NtMYB12 was Up-Regulated by Low Pi Treatment

To determine whether NtMYB12 is regulated by Pi deficiency, the promoter sequence of NtMYB12 in tobacco was analyzed using PlantCare (Lescot et al., 2002). The low Pi-responsive elements W-box and PHO-like were found in the NtMYB12 promoter (Figure 3A), indicating that NtMYB12 might be involved in the Pi signaling pathway in tobacco.

Figure 3.

Expression patterns of NtMYB12 in different organs and effects of Pi deprivation on the expression of NtMYB12 in tobacco. (A) Analysis of the NtMYB12 promoter. (B) Relative transcript levels of NtMYB12 in different tissues of tobacco. (C) Time course of NtMYB12 expression in response to low Pi stress. Thirty-day old seedlings were grown in nutrient solution with low Pi (LP; 0.02mM Pi) for 7 days. Data are the means ± SDs of five biological replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

We further checked the expression of NtMYB12 in the roots, stems, leaves, and flowers of tobacco. NtMYB12 was expressed in all of the organs examined, with the highest levels in stems and the lowest levels in flowers (Figure 3B). Moreover, the expression of NtMYB12 was significantly increased under low Pi conditions in roots, stems, and leaves up to 7 days (Figure 3C), implying that this gene may play a regulatory role in tobacco response and adaptation to low Pi levels.

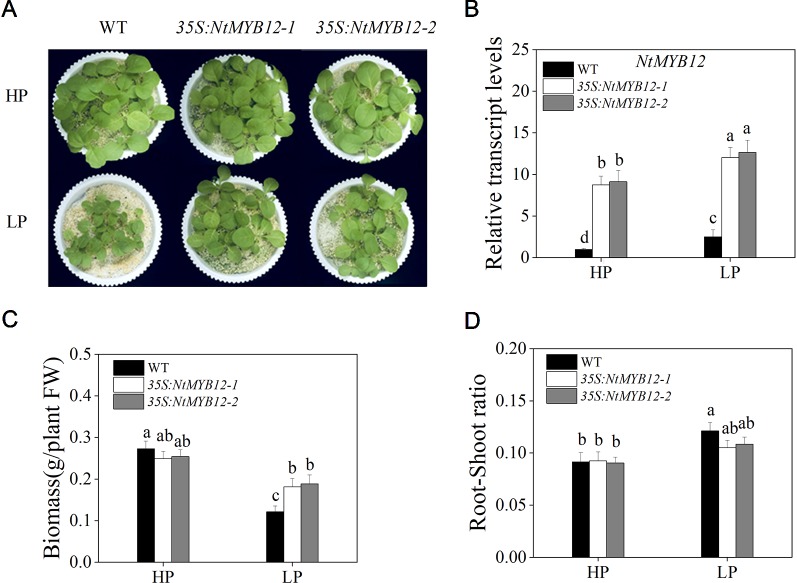

Overexpression of NtMYB12 Enhanced Tobacco Tolerance to Low Pi Stress

To determine the function of NtMYB12, twenty transgenic tobacco lines were generated by introducing the NtMYB12-overexpression construct. Two independent transgenic lines (named 35S:NtMYB12-1 and 35S:NtMYB12-2) were identified by Southern blot analysis and used in this study (Figure S1 and Figure 4). Under Pi-sufficient conditions (HP; 1 mM Pi), the phenotype and biomass of 35S:NtMYB12 plants were not significantly different from those of wild-type (WT) plants (Figure 4A). Under Pi-deficient conditions (LP; 0.02 mM Pi), the biomass in 35S:NtMYB12 plants was significantly higher than in WT plants (Figures 4B, C). However, we also found that the root–shoot ratios were not significantly different between 35S:NtMYB12 plants and WT under low Pi stress (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Expression of NtMYB12 in transgenic tobacco and characterization of the WT and transgenic tobacco. (A) Characterization of the WT and transgenic tobacco under HP and LP conditions. (B) Relative transcript levels of NtMYB12 in WT and transgenic plants. (C) Biomass of the WT and transgenic plants under HP and LP conditions. (D) Root–shoot ratio of the WT and transgenic plants under HP and LP conditions. Sixteen-day-old seedlings were transferred to the full-strength culture solution and supplied with high Pi (HP; 1mM Pi) or low Pi (LP; 0.02mM Pi) for 21 days. FW, fresh weight. Data are the means ± SDs of five biological replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

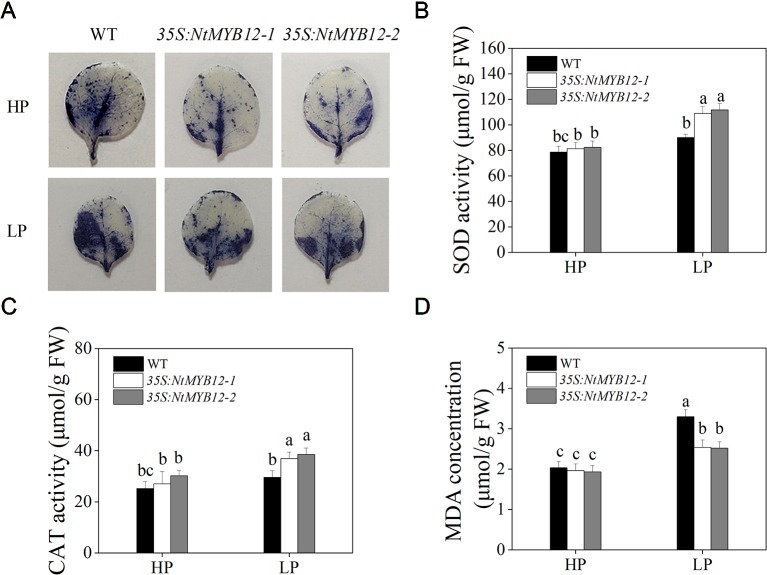

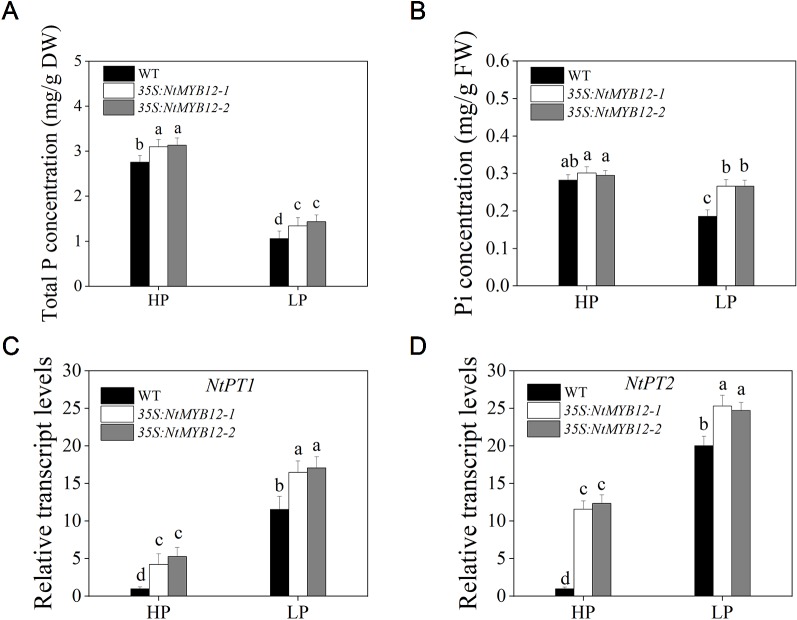

To determine the antioxidant capacity of 35S:NtMYB12 plants under HP and LP conditions, we investigated the accumulation of superoxide (O2-) by nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) staining. A large amount of this ROS was detected in the leaves of tobacco WT plants but not in transgenic plants (Figure 5A). We also checked leaf concentrations of SOD, CAT, and MDA and found that NtMYB12 overexpression in tobacco significantly increased the plant antioxidant capacity (Figures 5B–D). Total P concentration and Pht1 family gene expression in 35S:NtMYB12 plants under HP and LP conditions were also assessed. Plants overexpressing NtMYB12 had higher P concentrations under both HP and LP conditions (Figure 6); this finding was consistent with the expression pattern of genes belonging to the Pht1 family. All of these results suggested that NtMYB12 might play a crucial role under low Pi stress conditions.

Figure 5.

Effects of P treatment on antioxidant enzymes of WT and transgenic tobacco leaves. (A) Detection of Superoxide (O2-) by NBT staining in tobacco seedlings. (B) SOD activity of the WT and transgenic plants. (C) CAT activity of the WT and transgenic plants. (D) MDA concentration of the WT and transgenic plants. Sixteen-day-old seedlings were transferred to the full-strength culture solution and supplied with high Pi (HP; 1mM Pi) or low Pi (LP; 0.02mM Pi) for 21 days. FW, fresh weight. Data are the means ± SDs of five biological replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Total P, Pi concentration, and relative transcript levels of two members of the tobacco Pht1 family in WT and 35S:NtMYB12 plants under HP and LP conditions. (A–B) Total P and Pi concentration of WT and transgenic plants in tobacco. (C–D) Effect of NtMYB12 overexpression on relative transcript levels of NtPT1 and NtPT2 in tobacco under HP and LP conditions. Sixteen-day-old seedlings were transferred to the full-strength culture solution and supplied with high Pi (HP; 1mM Pi) or low Pi (LP; 0.02mM Pi) for 21 days. The whole plants of the WT and transgenic plants were used for measuring Total P and Pi concentration and for RNA extraction. FW, fresh weight; DW, dry weight. Data are the means ± SDs of five biological replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Overexpression of NtMYB12 Resulted in Flavonol Accumulation in Both Pi-Deficient and Pi-Sufficient Conditions

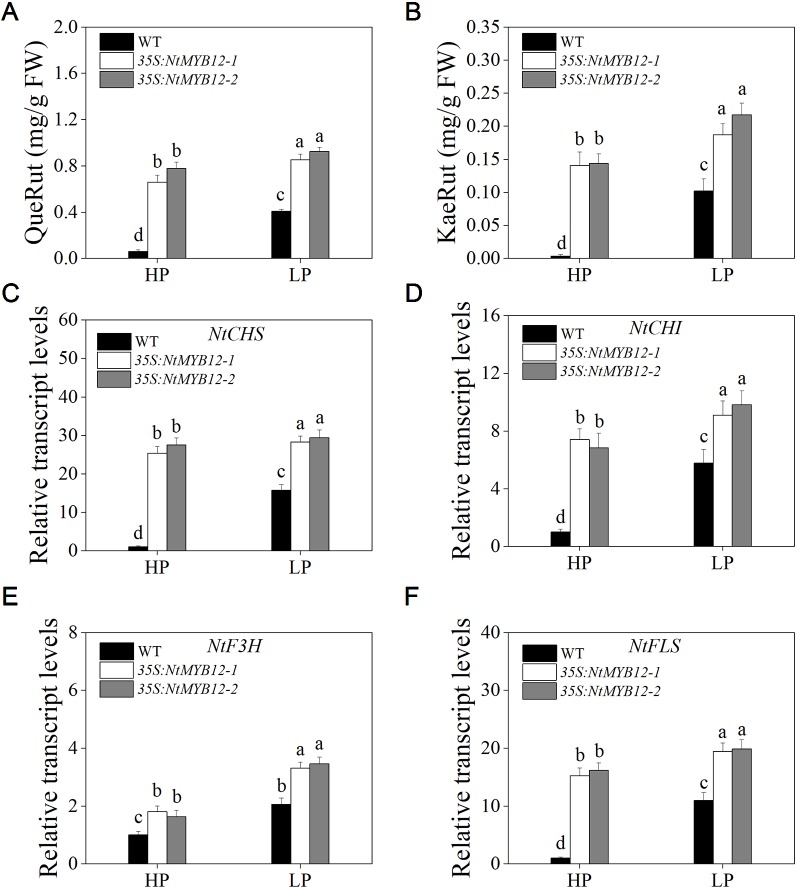

The function of flavonol biosynthesis in tobacco was investigated by measuring the flavonol concentration in the leaves of 35S:NtMYB12 and WT tobacco plants growing under Pi-deficient and Pi-sufficient conditions. The major flavonols (rutin and kaempferol rutinoside) were detected in both the wild-type and overexpressing plants. In 35S:NtMYB12 leaves, flavonol concentration was 10-fold higher than in WT under HP conditions (Figures 7A, B). Under LP conditions, the 35S:NtMYB12 plants showed a significantly increased flavonol concentration while WT plants did not, implying that NtMYB12 is involved in the flavonol biosynthetic pathway and Pi signaling pathway in tobacco.

Figure 7.

Quantification of flavonol concentration and relative transcript levels of majority genes encoding flavonoid biosynthetic enzymes in WT and 35S:NtMYB12 plants under HP and LP conditions. (A–B) QueRut and KaeRut concentrations of WT and overexpression tobacco plants. (C–F) Effect of NtMYB12 overexpression on relative transcript levels of flavonol biosynthetic genes in tobacco. Sixteen-day-old seedlings were transferred to the full-strength culture solution and supplied with high Pi (HP; 1mM Pi) or low Pi (LP; 0.02mM Pi) for 21 days. The whole plants of the WT and transgenic plants were used for RNA extraction. FW, fresh weight; CHS, chalcone synthase; CHI, chalcone isomerase; F3H, flavanone 3-hydroxylase; FLS, flavonol synthase. Data are the means ± SDs of five biological replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

To detect whether NtMYB12 is involved in Pi-supply-regulated flavonol biosynthesis, we analyzed the expression levels of genes involved in flavonol biosynthesis. We found that the expression levels of the genes CHS, CHI, and FLS in the leaves of 35S:NtMYB12 plants were significantly higher than in the WT plants under HP conditions, suggesting increased flavonol biosynthesis in the 35S:NtMYB12 plants compared with that in the WT plants (Figures 7C–F).

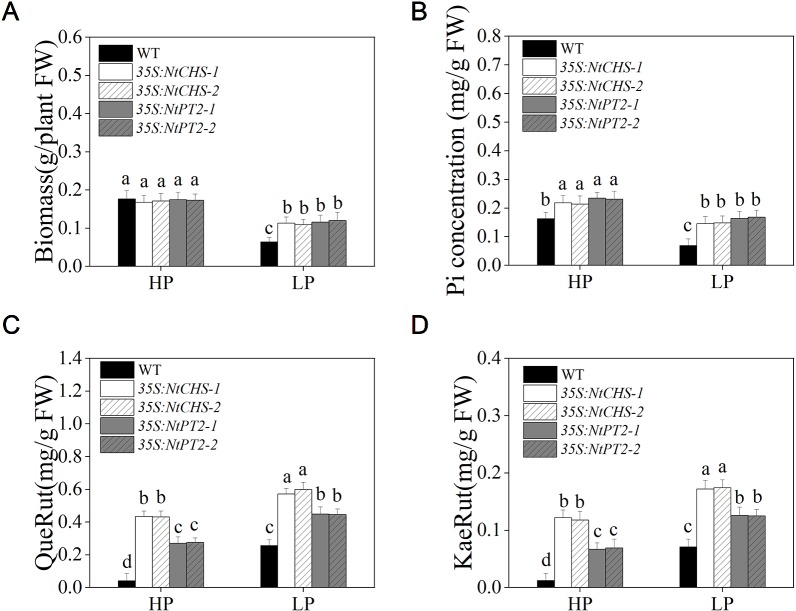

NtCHS- and NtPT2-Overexpressing Transgenic Plants Enhanced Low Pi Tolerance

To further determine whether NtMYB12 plays a critical role in regulating the transcription of flavonol biosynthesis-related genes and Pht1 family genes, NtCHS-overexpressing independent transgenic lines (named 35S:NtCHS-1 and 35S:NtCHS-2) and NtPT2-overexpressing independent transgenic lines (named 35S:NtPT2-1 and 35S:NtPT2-2) were selected for further analyses. The expression levels of NtCHS and NtPT2 were significantly up-regulated under low Pi stress conditions in WT plants, implying that the two genes play a key role in the Pi-starvation signaling pathway (Figure S2). We further detected the biomass, Pi concentration and flavonol concentration of 35S:NtCHS and 35S:NtPT2 plants under HP and LP conditions. Interesting, the results showed that the 35S:NtCHS and 35S:NtPT2 transgenic tobacco also had a similar phenotype to NtMYB12 transgenic tobacco, such as increased flavonol and Pi concentrations and higher tolerance to low Pi stress under low Pi conditions (Figure 8 and Figure S2), suggesting that NtCHS and NtPT2 were the key downstream target genes of NtMYB12.

Figure 8.

Biomass, Pi concentration, and flavonol concentration in WT, 35S:NtCHS, and 35S:NtPT2 transgenic plants under HP and LP conditions. (A–B) Biomass and Pi concentration of the WT and transgenic plants under HP and LP conditions. (C–D) QueRut and KaeRut concentrations of the WT and transgenic tobacco plants. Sixteen-day-old seedlings were transferred to the full-strength culture solution and supplied with high Pi (HP; 1mM Pi) or low Pi (LP; 0.02mM Pi) for 14 days. FW, fresh weight. Data are the means ± SDs of three biological replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Discussion

NtMYB12 is Involved in Flavonol Biosynthesis in Tobacco

In this study, we report a new PFG-type MYB transcription factor, NtMYB12, as a gene that regulates flavonol production in tobacco; this is similar to reports for PtMYB12 and AtMYB12 (Figures 1 and 2). There are various kinds of flavonol glycosides in plants. When NtMYB12 was expressed at high levels in tobacco, significant increases were observed in two flavonols, rutin and kaempferol glycoside (Figures 7A, B). This result was consistent with those reported by Luo et al. (2008) and Zhai et al. (2019)

Previously, we reported that flavonols accumulate in tobacco plants grown under Pi deficiency (Jia et al., 2015). In the present study, the flavonol concentration of NtMYB12 transgenic tobacco significantly increased under HP and LP conditions. Remarkably, we also found that the anthocyanin concentration and the relative transcript levels of anthocyanin biosynthesis genes NtDFR of 35S:NtMYB12 plants did not significantly increase under either LP or HP conditions (Figure S3), suggesting that NtMYB12 plays a crucial role in the flavonol synthesis pathway. The roles of CHS and FLS in flavonol biosynthesis have been reported in other plants such as Arabidopsis, pear, and tomato. In this study, we also found that the expression patterns of the genes encoding CHS, CHI, and FLS were consistent with the patterns of flavonol accumulation in tobacco leaves (Figures 7C–F). Moreover, NtCHS-overexpressing plants had significantly increased flavonol concentration and a similar phenotype to NtMYB12-overexpressing plants (Figures 8 and S2) under low Pi stress conditions, suggesting that NtCHS is a crucial downstream target gene of NtMYB12.

Overexpression of NtMYB12 Enhances Plant Resistance to Low Pi as Part of a Complex Network

Previous studies showed that MYB TFs are involved in various biotic and abiotic stresses (Abe, 2002; Agarwal et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2018; Zhao, 2019). Dai et al. (2012) first reported that OsMYB2P-1, an R2R3-MYB transcription factor, is involved in the regulation of phosphate-starvation responses in rice. Overexpression of OsMYB2P-1 led to greater expression of high-affinity phosphate transporter genes (Pht1) such as OsPT6, OsPT8, and OsPT10 under Pi-sufficient conditions, implying that OsMYB2P-1 is a key transcriptional factor associated with Pi-starvation signaling in rice. Until now, the function of the MYB members involved in the Pi-starvation signaling pathway was still unclear in tobacco. In our previous study, a large number of flavonoid biosynthesis-related genes were cloned in tobacco (data not shown). However, we found that only the expression of NtMYB12 was abundantly expressed under Pi deficiency. In this study, we further investigated the function of NtMYB12 in the Pi signaling pathway and found that overexpression of NtMYB12 significantly increased Pi and total P concentration, suggesting that this gene participates in the Pi signaling pathway in tobacco (Figures 2, 3, and 6).

Some studies showed that overexpression of the rice phosphate transporter gene OsPT2 enhanced soybean tolerance to low phosphorus levels (Chen et al., 2015). Similarly, in a previous study, we observed that overexpression of OsPT8 enhanced tobacco tolerance to phosphorus starvation, which may be a consequence of the increased expression of NtPT1 and NtPT2 and higher Pi uptake by tobacco roots (Song et al., 2017). In this study, overexpression of NtMYB12 increased NtPT1 and NtPT2 expression in tobacco plants growing under Pi-sufficient conditions, suggesting that NtMYB12 may be involved in the downstream regulation of tobacco Pi transporters under Pi restrictions (Figure 6). In our previous studies, we found that overexpression of NtPT2 could enhance resistance to low Pi stress (Jia et al., 2017; Jia et al.,2018; Luo et al., 2019). Remarkably, in this work, we found that 35S:NtPT2 transgenic tobacco increased not only the Pi concentrations but also the flavonol concentration under low Pi stress conditions, showing a similar phenotype to NtMYB12-overexpressing plants at low Pi stress (Figures 4, 8, and S2), suggesting that NtMYB12 enhances resistance to low Pi stress by regulating the phosphate transporter NtPT2 in tobacco plants. In addition, we also found that the expression level of flavonol synthesis-related genes (NtCHS and NtFLS) significantly increased in 35S:NtPT2 transgenic tobacco under both HP and LP conditions (Figure S4), implying that the high-affinity phosphate transporter NtPT2 might be involved in regulating the flavonol biosynthetic pathway; this needs further study.

Previous studies have shown that flavonoids are powerful antioxidants and are involved in abiotic stress responses (Martinez et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2019). We found that ROS accumulation was decreased in NtMYB12 transgenic tobacco under low Pi treatment (Figure 5), which was consistent with the concentration of MDA. Thus, it is likely that NtMYB12 may promote low Pi tolerance at least partially through the antioxidant activity of flavonoids.

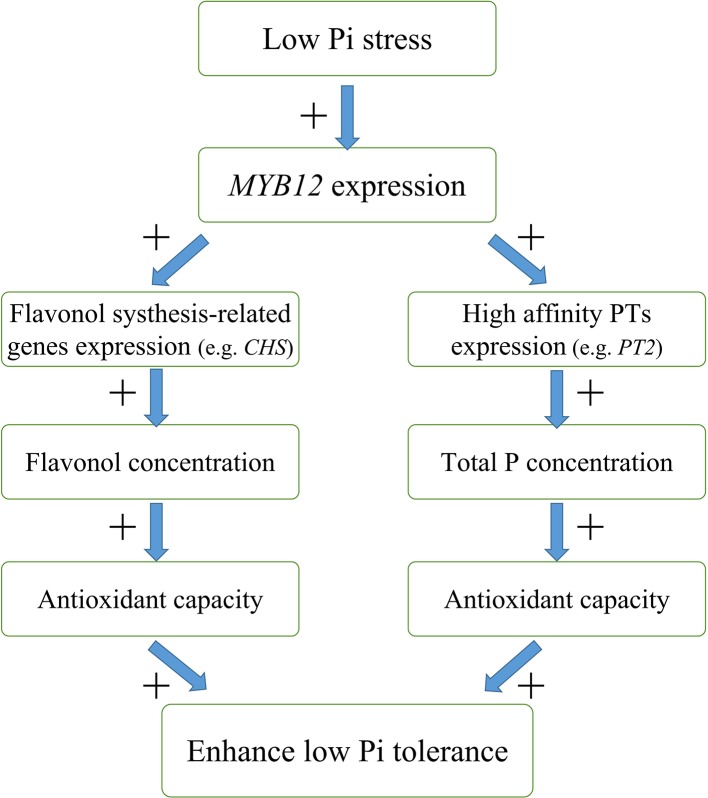

In this study, we found that overexpression of NtMYB12 increases flavonol concentration, enhances the activity of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant systems, and increases the total P concentration, thus improving the ability of plants to cope with low Pi stress. Based on our results, we propose a possible model for the regulation mechanism of NtMYB12 in the Pi signaling pathway in tobacco under low Pi conditions (Figure 9): (1) NtMYB12 expression in tobacco is up-regulated, (2) then, the expressions of flavonol synthesis-related genes and Pht1 family genes are significantly up-regulated (3) increasing flavonol and total P concentration; (4) as a result, the antioxidant capacity rises; these events may result in enhanced tolerance to low phosphate levels. As a whole, our results suggest that NtMYB12 might function in a complex network that leads to enhanced tolerance to Pi starvation.

Figure 9.

Possible model for the mechanism of interaction between NtMYB12, flavonol synthesis, and total P concentration under low Pi stress conditions in tobacco. The model is based on the results presented here. + indicates positive regulation.

Conclusion

We characterized the functions of NtMYB12 as an enhancement factor in low Pi responsiveness. The expression of NtMYB12 was up-regulated by low Pi stress, resulting in the activation of NtCHS and NtPT2 transcription, followed by the accumulation of flavonols and total P and then an enhancement of tolerance to low Pi stress. A better understanding of the regulatory networks underlying flavonol biosynthesis and plant responses to Pi deficiency could help in the breeding of plant varieties with improved phosphorus use efficiency.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

HJ, DW, and CY designed this study. ZS and YL did the main experimental work. All of the authors carried out the field experiments. WW and YL made a modification of the manuscript. HJ and ZS wrote the manuscript. All of the authors read and approved this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31301837), the Outstanding Young Teachers Development Program of Henan Province (2019GGJS043), and the Foundation of the Zhoukou Branch of Henan Tobacco Company (2019411600240174).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2019.01683/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abe H. (2002). Arabidopsis AtMYC2 (bHLH) and AtMYB2 (MYB) function as transcrip-tional activators in abscisic acid signaling. Plant Cell. 15, 63–78. 10.1105/tpc.006130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal M., Hao Y. J., Kapoor A., Dong C. H., Fujii H., Zheng X. W., et al. (2006). A R2R3 type MYB transcription factor is involved in the cold regulation of CBF genes and in acquired freezing tolerance. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 37636– 37645. 10.1074/jbc.m605895200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bariola P. A., Maclntosh G. C., Green P. J. (1999). Regulation of S-like ribonuclease levels in Arabidopsis. Antisense inhibition of RNS1or RNS2 elevates anthocyanin accumulation. Plant Physiol. 119, 331–342. 10.1104/pp.119.1.331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borevitz J. O., Xia Y., Blount J., Dixon R. A., Lamb C. (2000). Activation tagging identifies a conserved MYB regulator of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 12, 2383–2394. 10.2307/3871236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang M. X., Gu M., Xia Y. W., Dai X. L., Dai C. R., Zhang J., et al. (2019). OsPHT1,3 mediates uptake, translocation and remobilization of phosphate under extremely low phosphate regimes. Plant Physiol. 179, 656–670. 10.1104/pp.18.01097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A. Q., Gu M., Sun S. B., Zhu L. L., Hong S., Xu G. H. (2011). Identification of two conserved cis-acting elements, MYCS and P1BS, involved in the regulation of mycorrhiza-activated phosphate transporters in eudicot species. New Phytol. 189, 1157–1169. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03556.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G. H., Yan W., Yang S. P., Wang A., Gai J. Y., Zhu Y. L. (2015). Overexpression of rice phosphate transporter gene OsPT2 enhances tolerance to low phosphorus stress in soybean. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 17, 469–482. 10.1016/j.scienta.2014.07.037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Pan X. H., Li Y. T., Cui L. J., Zhang Y. C., Zhang Z. M., et al. (2017). Identification and characterization of chalcone synthase gene family members in Nicotiana tabacum. J. Plant Growth Regul. 36, 374–384. 10.1007/s00344-016-9646-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Wu F., Li Y., Qian Y., Pan X., Li F., et al. (2019). NtMYB4 and NtCHS1 are critical factors in the regulation of flavonoid biosynthesis and are involved in salinity responsiveness. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 178. 10.3389/fpls.2019.00178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiou T. J., Lin S. I. (2011). Signaling network in sensing phosphate availability in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 62, 185–206. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X. Y., Wang Y. Y., Yang A., Zhang W. H. (2012). OsMYB2P-1, an R2R3 MYB transcription factor, Is involved in the regulation of phosphate-starvation responses and root architecture in rice. Plant Physiol. 159, 169–183. 10.1104/pp.112.194217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubos C., Stracke R., Grotewold E., Weisshaar B., Martin C., Lepiniec L. (2010). MYB transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 573–581. 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco-Zorrilla J. M., González E., Bustos R., Linhares F., Leyva A., PazAres J. (2004). The transcriptional control of plant responses to phosphate limitation. J. Exp. Bot. 55, 285–293. 10.1093/jxb/erh009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez A., Zhao M., Leavitt J. M., Lloyd A. M. (2008). Regulation of the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway by the TTG1/bHLH/Myb transcriptional complex in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant J. 53, 814–827. 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2007.03373.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbwirth H. (2010). The creation and physiological relevance of divergent hydroxylation patterns in the flavonoid pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 11, 595–621. 10.3390/ijms11020595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holton T. A., Edwina C. C. (1995). Cornish ECGenetics and biochemistry of anthocyanin biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 7, 1071–1083. 10.2307/3870058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain A., Nagarajan V. K., Raghothama K. G. (2012). Transcriptional regulation of phosphate acquisition by higher plants. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 69, 3207–3224. 10.1007/s00018-012-1090-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia H. F., Ren H. Y., Gu M., Zhao J. N., Sun S. B., Zhang X., et al. (2011). The phosphate transporter gene OsPht1,8 is involved in phosphate homeostasis in rice. Plant Physiol. 156, 1164–1175. 10.1104/pp.111.175240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia H. F., Wang J. A., Yang Y. F., Liu G. S., Bao Y., Cui H. (2015). Changes in flavonol concentration and transcript levels of genes in the flavonoid pathway in tobacco under phosphorus deficiency. Plant Growth Regul. 76, 225–231. 10.1007/s10725-014-9990-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jia H. F., Zhang S. T., Wang L. Z., Yang Y. X., Zhang H. Y., Cui H., et al. (2017). OsPht1,8, a phosphate transporter, is involved in auxin and phosphate starvation response in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 68, 5057–5068. 10.1093/jxb/erx317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia H. F., Song Z. P., Wu F. Y., Ma M., Li Y. T., Han D., et al. (2018). Low selenium increases the auxin concentration and enhances tolerance to low phosphorous stress in tobacco. Environ. Exp. Bot. 153, 127–134. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2018.05.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan N., Adhami V. M., Mukhtar H. (2010). Apoptosis by dietary agents for prevention and treatment of prostate cancer. Endocr.-Relat. Cancer. 17, R39–R52. 10.1677/ERC-09-0262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn B. M., Geisler M., Bigler L., Ringli C. (2011). Flavonols accumulate asymmetrically and affect auxin transport in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 156, 585–595. 10.1093/ajcn/74.4.418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Nei M., Dudley J., Tamura K. (2008). MEGA: a biologist-centric software for evolutionary analysis of DNA and protein sequences. Brief. Bioinform. 9, 299–306. 10.1093/bib/bbn017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lescot M., Déhais P., Thijs G., Marchal K., Moreau Y., Van de Peer Y., et al. (2002). Plantcare, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 325–327. 10.1093/nar/30.1.325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. T., Gu M., Zhang X., Zhang J., Fan H. M., Li P. P., et al. (2014). Engineering a sensitive visual tracking reporter systemfor real-time monitoring phosphorus deficiency in tobacco. Plant Biotechnol. J. 12 (6), 674–684. 10.1111/pbj.171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Chen M., Wang S. L., Ning J., Ding X. H., Chu Z. H. (2015). AtMYB11regulates caffeoylquinic acid and flavonol synthesis in tomato and tobacco. Plant Cell. 122, 309–319. 10.1007/s11240-015-0767-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li S. (2014). Transcriptional control of flavonoid biosynthesis: fne-tuning of the MYB-bHLH-WD40 (MBW) complex. Plant Signaling Behavior. 8, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Osbourn A., Ma P. (2015). MYB transcription factors as regulators of phenylpropanoid metabolism in plants. Mol. Plant 8, 689–708. 10.1016/j.molp.2015.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. Y., Wang P. L., Zhang T. Q., Li Y. B., Wang Y. Y., Gao C. Q. (2018). Comprehensive analysis of BpHSP genes and their expression under heat stresses in Betula platyphylla. Environ. Exp. Bot. 152, 167–176. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2018.04.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25, 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J., Eugenio B., Lionel H., Adrian P., Ricarda N., Paul B., et al. (2008). AtMYB12 regulates caffeoyl quinic acid and flavonol synthesis in tomato: expression in fruit results in very high levels of both types of polyphenol. Plant J. 56, 316–326. 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2008.03597.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y., Wei Y., Sun S., Wang J., Wang W., Han D., et al. (2019). Selenium modulates the level of auxin to alleviate the toxicity of cadmium in tobacco. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 3772. 10.3390/ijms20153772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch J. P. (2011). Root phenes for enhanced soil exploration andphosphorus acquisition: tools for future crops. Plant Physiol. 156, 1041–1049. 10.2307/41435018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marschner H. (1995). Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants (London: Academic Press; ). [Google Scholar]

- Martinez V., Mestre T. C., Rubio F., Girones-Vilaplana A., Moreno D. A., Mittler R., et al. (2016). Accumulation of flavonols over hydroxycinnamic acids favors oxidative damage protection under abiotic stress. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 838. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrtens F., Kranz H., Bednarek P., Weisshaar B. (2005). The Arabidopsis transcription factor MYB12 is a flavonol-specific regulator of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 138, 1083–1096. 10.1104/pp.104.058032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesi N., Jond C., Debeaujon I., Caboche M., Lepiniec L. (2001). The Arabidopsis TT2 gene encodes an R2R3 MYB domain protein that acts as a key determinant for proanthocyanidin accumulation in developing seed. Plant Cell. 13, 2099–2114. 10.1105/tpc.13.9.2099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niggeweg R., Michael A. J., Martin C. (2004). Engineering plants with increased levels of the antioxidant chlorogenic acid. Nat. Biotechnol. 22, 746–754. 10.1038/nbt966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijveldt R. J., van N. E., van H. D. E., Boelens P. G., van N. K., van L. P. A. (2001). Flavonoids: a review of probable mechanisms of action and potential applications. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 74, 418–425. 10.1093/ajcn/74.4.418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan W. B., Wu Y. R., Xie Q. (2019). Regulation of ubiquitination is central to the phosphate starvation response. Trends Plant Sci. 24, 755–769. 10.1016/j.tplants.2019.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. E., Jakobsen I., Grønlund M., Smith F. A. (2011). Roles of arbuscular mycorrhizas in plant phosphorus nutrition: interactions between pathways of phosphorus uptake in arbuscular mycorrhizal roots have important implications for understanding and manipulating plant phosphorus acquisition. Plant Physiol. 156, 1050–1057. 10.1104/pp.111.174581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Z. P., Shao H. F., Huang H. G., Shen Y., Wang L. Z., Wu F. Y., et al. (2017). Overexpression of the phosphate transporter gene, OsPT8, improves the Pi and selenium concentrations in, Nicotiana tabacum. Environ. Exp. Bot. 137, 158–165. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2017.02.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song Z. P., Fan N. B., Jiao G. Z., Liu M. H., Wang X. Y., Jia H. F. (2019). Overexpression of OsPT8 increases auxin content and enhances tolerance to high-temperature atress in Nicotiana tabacum. Genes. 10, 809. 10.3390/genes10100809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracke R., Jahns O., Keck M., Tohge T., Niehaus K., Fernie A. R., et al. (2010). Analysis of production of flavonol glycosides-dependent flavonol glycoside accumulation in Arabidopsis thaliana plants reveals MYB11-, MYB12- andMYB111-independent flavonol glycoside accumulation. New Phytol. 188, 985–1000. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03421.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance C. P., Uhde-Stone C., Allan D. L. (2003). Phosphorus acquisition and use: critical adaptati-ons by plants for securing a nonrenewable resource. New Phytol. 157, 423–447. 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00695.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Xu C., Wang C., Wang Y. (2012). Characterization of a eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A homolog from Tamarix androssowii involved in plant abiotic stress tolerance. BMC Plant Biol. 12, 118. 10.1186/1471-2229-12-118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Meng D., Wang A., Li T., Jiang S., Cong P., et al. (2013). The methylation of the PcMYB10 promoter is associated with green-skinned sport in Max Red Bartlett pear. Plant Physiol. 162, 885–896. 10.2307/41943270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkel S. B. (2001). Flavonoid biosynthesis. a colorful model for genetics, biochemistry, cell biology, and biotechnology. Plant Physiol. 126, 485–493. 10.1104/pp.126.2.485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q., Yin X. R., Zeng J. K., Ge H., Song M., Xu C. J., et al. (2014). Activator-and repressor-type MYB transcription factors are involved in chilling injury induced flesh lignifcation in loquat via their interactions with the phenylpropanoid pathway. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 4349–4359. 10.1093/jxb/eru208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B. C., Song Z. H., Li C. N., Jiang J. H., Zhou Y. Y., Wang R. P., et al. (2018). RSM1,an Arabidopsis MYB protein, interacts with HY5/HYH to modulate seed germination and seedling development in response to abscisic acid and salinity. PloS Genet. 14 (12), e1007839. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai R., Wang Z., Zhang S., Meng G., Song L., Wang Z., et al. (2016). Two MYB transcription factors regulate flavonoid biosynthesis in pear fruit (Pyrus bretschneideri Rehd.). J. Exp. Bot. 67, 1275–1284. 10.1093/jxb/erv524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai R., Zhao Y. X., Wu M., Yang J., Li X. Y., Liu H. T., et al. (2019). The MYB transcription factor PbMYB12b positively regulates flavonol biosynthesis in pear fruit. BMC Plant Biol. 19. 10.1186/s12870-019-1687-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. Y. (2019). Overexpression of an R2R3 MYB Gene, GhMYB73, increases tolerance to salt stress in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Sci. 286, 28–36. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2019.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Jiao F., Wu Z., Li Y., Wang X., He X., et al. (2008). OsPHR2 is involved in phosphate-starvation signaling and excessive phosphate accumulation in shoots of plants. Plant Physiol. 146, 1673–1686. 10.1104/pp.107.111443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.