Abstract

Patient: Male, 75-year-old

Final Diagnosis: Pulmonary histoplasmosis

Symptoms: Altered mental status • cough • shortness of breath

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Pulmonology

Objective:

Rare co-existance of disease or pathology

Background:

Histoplasmosis results from the inhalation of spores from the fungus, Histoplasma capsulatum. A case is presented of pulmonary histoplasmosis associated with altered mental state and hypercalcemia following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Case Report:

A 75-year-old man with a five-day history of AML treated with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, presented with weakness, fatigue, and slow mentation. Computed tomography (CT) of the brain was unremarkable. Laboratory investigations showed serum albumin of 2.9 g/dL, calcium of 11.6 mg/dL, ionized calcium of 1.55 mmol/L, parathyroid hormone (PTH) <6.3 pg/mL, and 25-hydroxy vitamin D of 14.4 ng/mL. Treatment began with intravenous cefepime 1 gm bid, normal saline, and the bisphosphonate, pamidronate, administered as a single dose. Three days later, his clinical status declined. He developed a dry productive cough, his oxygen saturation (O2 Sat) was 90%, and his mental status worsened. Chest CT showed diffuse bilateral lung infiltrates with ground glass opacities. Bronchioalveolar lavage and transbronchial biopsy were negative for Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (PJP). The CMV viral load was 195 IU/mL. Urinalysis for Histoplasma antigen and the Fungitell® assay were positive. Treatment commenced with intravenous voriconazole (250 mg, bid) and ganciclovir (5 mg/kg, bid). A left lower lobe transbronchial lung biopsy was positive for Histoplasma capsulatum and negative for CMV.

Conclusions:

This case report has highlighted the need for awareness of the diagnosis of histoplasmosis in patients with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation who present with an altered mental state in the setting of hypercalcemia.

MeSH Keywords: Histoplasmosis, Hypercalcemia, Stem Cell Transplantation

Background

Histoplasmosis is the most common endemic mycosis in the US and results from the inhalation of spores from the fungus, Histoplasma capsulatum [1]. A case is presented of pulmonary histoplasmosis presenting with nonspecific symptoms and hypercalcemia in the setting of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Few cases have previously been reported of pulmonary histoplasmosis in patients following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation [2].

Case Report

A 75-year-old man with a history of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and resolved hepatitis C virus (HCV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection received induction chemotherapy with idarubicin and consolidation therapy with cytarabine. A follow-up bone marrow biopsy showed complete remission. He underwent allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation following a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen with cyclophosphamide, fludarabine, and total body irradiation. After 144 days, he presented with a five-day history of weakness, fatigue, and slow mentation. He denied skin rash, abdominal pain, diarrhea, shortness of breath, cough, sputum production, or other symptoms. His vital signs were normal, with a blood pressure of 97/58 mmHg, a temperature 36.2°C, a pulse rate of 87 bpm, a respiratory rate of 18 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation (O2 Sat) of 97% in room air.

On physical examination, he was somnolent, unable to recognize his spouse, but was without focal neurological deficit. Computed tomography (CT) of the brain was unremarkable. Laboratory investigations were significant for a white blood cell count (WCC) of 5.2×103/ul, an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of 3.3×109/L, a hemoglobin of 10.7 g/dL, hematocrit of 12.6%, platelet count of 37 × 103/ul, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) of 30 mg/dL, creatinine of 1.26 mg/dL, albumin of 2.9 g/dL, calcium 11.6 mg/dL, ionized calcium of 1.55 mmol/L, parathyroid hormone (PTH) <6.3 pg/mL, 25-hydroxy vitamin D of 14.4 ng/mL. Fifteen days before admission, his calcium levels were at 9.0 mg/dL. Serologic tests for Cryptococcal antigen and Aspergillus galactomannan were negative, and EBV serology was positive. A lumbar puncture test was unremarkable. Treatment began with intravenous cefepime 1 gm bid, normal saline at 150 ml/h per 1 L, and the bisphosphonate, pamidronate, administered as a single dose of 90 mg.

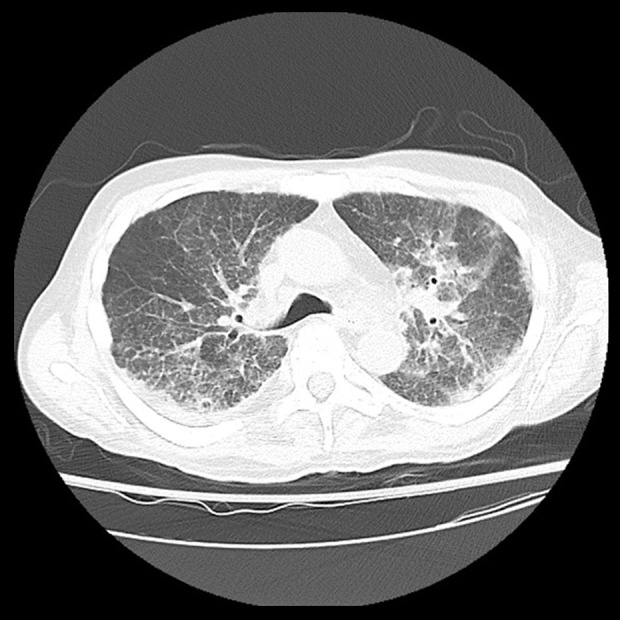

Three days later, the patient’s clinical status continued to decline. He developed a dry productive cough. His O2 Sat was 90%, and his mental status declined. A chest CT showed bilateral diffuse lung infiltrates with ground glass opacities (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Computed tomography (CT) imaging of a 75-year-old man with pulmonary histoplasmosis and hypercalcemia following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Diffuse bilateral lung infiltrates with ground glass opacities.

Treatment with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) at 5 mg/kg tid commenced for possible Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonitis (PJP). Bronchioalveolar lavage and transbronchial biopsy were negative for PJP, and the CMV viral load was 195 IU/mL. Urinalysis for Histoplasma antigen and the Fungitell® assay were positive.

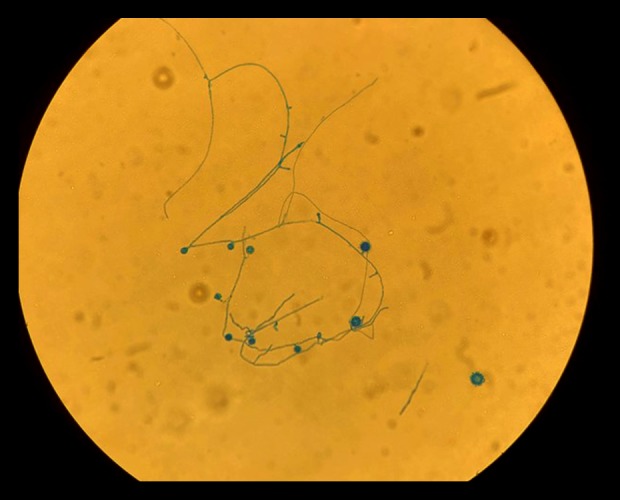

On further review of the patient’s history, he had spent most of his life in the Ohio River Valley area. A provisional diagnosis of pulmonary histoplasmosis and CMV pneumonitis was made. TMP/SMX was discontinued and treatment with intravenous voriconazole (250 mg, bid) and ganciclovir (5 mg/kg, bid) commenced. A left lower lobe transbronchial biopsy showed small budding yeast forms, which showed positive histochemical staining for Histoplasma capsulatum (Figure 2). The lung biopsy was negative for CMV.

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph of the bronchial culture of a lung sample from a 75-year-old man with pulmonary histoplasmosis and hypercalcemia following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The filamentous form of Histoplasmosis capsulatum is shown by lactophenol cotton blue staining for chitin in the wall of the fungus.

The diagnosis of pulmonary histoplasmosis was confirmed. The patient’s mental status progressively improved as the hypercalcemia resolved to a calcium level of 8.56 mg/dL. The patient was discharged from hospital on a seven-day course of ciprofloxacin, a six to 12-week course of voriconazole, and prophylactic HBV therapy with entecavir, prophylactic PJP therapy with atovaquone, and prophylactic HSV therapy with acyclovir. At one-month outpatient follow-up, the patient was noted to have persistently elevated liver enzyme levels. Voriconazole was discontinued, and posaconazole, a triazole antifungal agent, 400 mg every 12 hours, was commenced for a duration of 12 weeks. Repeat serum and urinalysis for Histoplasma antigen remained negative. The patient’s treatment was transitioned to a reduced secondary prophylactic dose of posaconazole. At a two-month outpatient follow-up, the patient remained asymptomatic but continued anti-infection prophylactic medications.

Discussion

A case report is presented that highlights one of many diverse presentations of histoplasmosis. This patient initially presented with the main complaint of altered mental status. General physical examination, review of his medications, and initial laboratory investigations were normal apart from hypercalcemia. Brain computed tomography (CT) imaging without contrast was negative for intracranial mass or hemorrhage. Lumbar puncture was negative for infection. However, only when the patient developed respiratory compromise and following further review of the patient’s history, which identified he had lived in an endemic area in Ohio, that a diagnosis of histoplasmosis was considered. The correlation between hypercalcemia and altered mental status was supported by the improvement in neurologic function when effective treatment commenced.

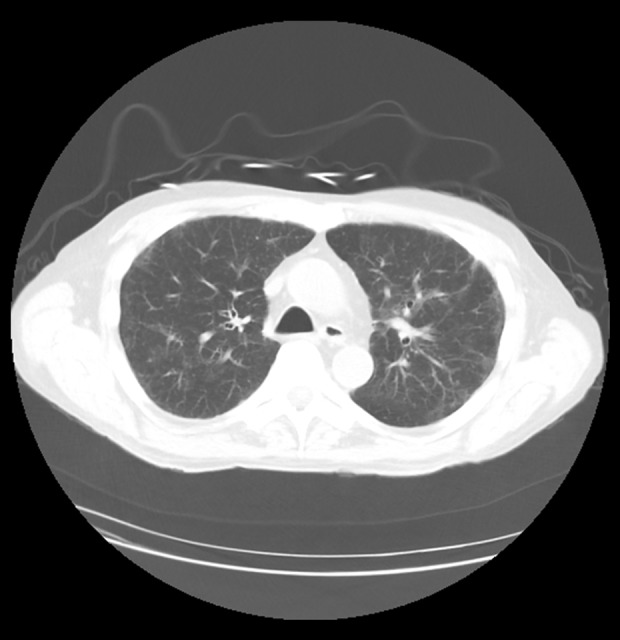

Although the presentation in this case was atypical, it was consistent with a diagnosis of acute pulmonary histoplasmosis. Although histoplasmosis can be self-limiting, patients with significant bilateral chest infiltrates or who are immunosuppressed require active treatment [3]. First-line therapy for pulmonary histoplasmosis is either with amphotericin B, fluconazole, or itraconazole. Typically, amphotericin B commences at one to two weeks and is replaced by itraconazole for an additional 12 weeks of therapy [3]. In this case, amphotericin treatment was not begun due to the moderate severity of the illness and possible drug interactions. This patient had a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 34%. Voriconazole was chosen as the first-line treatment, due to the black box warning regarding itraconazole in patients with underlying congestive heart failure [4,5]. The triazole antifungal agent, posaconazole was used as salvage therapy and had a lower profile for causing hepatic damage when compared with voriconazole. The patient continued to be at risk for developing chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis, given his underlying immunodeficiency state. Patients treated for histoplasmosis are typically maintained on antifungal therapy for at least 12–24 months, with follow-up chest CT at 6-monthly intervals [3]. In this case, follow-up chest CT (Figure 3) showed a significant resolution of the initial lung abnormalities while the patient was receiving posaconazole maintenance therapy.

Figure 3.

Computed tomography (CT) 3 months follow up imaging of a 75-year-old man with pulmonary histoplasmosis and hypercalcemia following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Major improvement of previous diffuse bilateral lung infiltrates with ground glass opacities.

There have been at least six previously reported cases of histoplasmosis associated with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation [2]. There have been previously published cases of histoplasmosis associated with hypercalcemia [6]. The diagnosis of histoplasmosis relies on a multidisciplinary approach that includes histopathology and microbiology examination, urine, and serology antibody tests [7]. Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis can present with hypercalcemia, which is attributed to increased vitamin D production from fungal granulomas [6]. In this case, the differential diagnoses on the initial presentation may have included malignancy and other granulomatous diseases, both of which are associated with hypercalcemia.

Conclusions

A case is presented of pulmonary histoplasmosis associated with altered mental state and hypercalcemia following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Although hypercalcemia a rare manifestation of histoplasmosis, lack of awareness of this association may lead to a delay in diagnosis and compromise patient outcome. This case report has highlighted the need for awareness of the diagnosis of histoplasmosis in patients with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation who present with an altered mental state in the setting of hypercalcemia.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

References:

- 1.Chu J, Feudtner C, Heydon K, et al. Hospitalizations for endemic mycoses: A population-based national study. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(6):822–25. doi: 10.1086/500405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Natarajan M, Swierzbinski MJ, Maxwell S, et al. Pulmonary histoplasma infection after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: Case report and review of the literature. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4(2):ofx041. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wheat LJ, Azar MM, Bahr NC, et al. Histoplasmosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30(1):207–27. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freifeld A, Proia L, Andes D, et al. Voriconazole use for endemic fungal infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53(4):1648–51. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01148-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmad SR, Singer SJ, Leissa BG. Congestive heart failure associated with itraconazole. Lancet. 2001;357(9270):1766–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04891-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khasawneh FA, Ahmed S, Halloush RA. Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis presenting with cachexia and hypercalcemia. Int J Gen Med. 2013;6:79–83. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S41520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hage CA, Ribes JA, Wengenack NL, et al. A multicenter evaluation of tests for diagnosis of histoplasmosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(5):448–54. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]