Abstract

Fecal samples from wild-caught common voles (n = 328) from 16 locations in the Czech Republic were screened for Cryptosporidium by microscopy and PCR/sequencing at loci coding small-subunit rRNA, Cryptosporidium oocyst wall protein, actin and 70 kDa heat shock protein. Cryptosporidium infections were detected in 74 voles (22.6%). Rates of infection did not differ between males and females nor between juveniles and adults. Phylogenetic analysis revealed the presence of eight Cryptosporidium species/genotypes including two new species, C. alticolis and C. microti. These species from wild-caught common voles were able to infect common and meadow voles under experimental conditions, with a prepatent period of 3–5 days post-infection (DPI), but they were not infectious for various other rodents or chickens. Meadow voles lost infection earlier than common voles (11–14 vs 13–16 DPI) and had significantly lower infection intensity. Cryptosporidium alticolis infects the anterior small intestine and has larger oocysts (5.4 × 4.9 μm), whereas C. microti infects the large intestine and has smaller oocysts (4.3 × 4.1 μm). None of the rodents developed clinical signs of infection. Genetic and biological data support the establishment of C. alticolis and C. microti as separate species of the genus Cryptosporidium.

Keywords: Experimental infection, molecular analyses, oocyst size, phylogeny, Rodentia, voles

Introduction

Cryptosporidium is an apicomplexan protist parasite that primarily infects the gastrointestinal epithelium of a broad range of vertebrate species including humans (Lv et al., 2009). Infections can be asymptomatic or can result in diarrhoea ranging from mild to severe. Disease severity depends mainly on the age and immune status of the host (Checkley et al., 2015; Baneth et al., 2016) Field studies have shown that genus Cryptosporidium is genetically diverse, with much of that diversity found in wildlife. Rodents are ubiquitous mammals comprising about 40% of mammalian diversity and occupying a wide range of habitats. Studies to date have shown that rodent species are predominantly parasitized with host-specific Cryptosporidium species and genotypes (Feng et al., 2007; Foo et al., 2007; Ziegler et al., 2007a; Kváč et al., 2008, 2013; Feng, 2010; Ng-Hublin et al., 2013; Stenger et al., 2015a, 2015b, 2018), although zoonotic species such as C. parvum and C. ubiquitum (Hajdušek et al., 2004; Rašková et al., 2013; Li et al., 2014; Perec-Matysiak et al., 2015) and livestock-specific species such as C. scrofarum, C. andersoni and C. baileyi (Ziegler et al., 2007a; Lv et al., 2009; Ng-Hublin et al., 2013; Danišová et al., 2017) have been reported. Despite a large number of studies, the diversity and biology of Cryptosporidium in several rodent hosts, including voles, have not been thoroughly characterized (Kváč et al., 2014; Stenger et al., 2018).

Early studies, relying on oocyst morphology to distinguish species, reported C. parvum, C. muris and Cryptosporidium sp. in voles (Chalmers et al., 1997; Torres et al., 2000; Sinski et al., 1993, 1998; Bull et al., 1998; Bajer et al., 2002; Bednarska et al., 2007). In more recent studies of voles, using more discriminatory genotyping tools to distinguish species, the prevalence of C. parvum was much lower than previously reported and C. muris was not detected. Additionally, common voles were not susceptible to C. muris, C. proliferans or C. andersoni under experimental conditions (Modrý et al., 2012). In contrast, Cryptosporidium muskrat genotypes I and II and Cryptosporidium isolates closely related to muskrat genotypes I and II have been reported frequently (online Supplementary Table S1). In the most recent study, the largest to date, Stenger et al. (2018) reported greater diversity of Cryptosporidium spp. infecting North American and European voles than previously known. They identified at least 18 different Cryptosporidium spp. by sequencing of the partial sequence of the small ribosomal subunit rRNA and actin genes in European and North American voles, and most of these were identified for the first time. Phylogenetic analyses indicated the Cryptosporidium spp. infecting voles from the different continents remained closely related (Stenger et al., 2018). Collectively, data from studies on voles show that they are host to at least 20 Cryptosporidium species and genotypes (see online Supplementary Table S1). Most of the genotypes lack biological data such as course of infection and host range.

We undertook the present study to extend knowledge of the occurrence and diversity of Cryptosporidium spp. infecting the common vole (Microtus arvalis). We selected two isolates from wild-caught common voles and, in accordance with ICZN nomenclature rules and criteria established by the scientific community studying Cryptosporidium (Xiao et al., 2004; Jirků et al., 2008; Fayer, 2010), we describe the morphometry of oocysts, determine phylogenetic relatedness at multiple genetic loci and report on the infectivity for several hosts (voles, laboratory and yellow-necked mice, laboratory rats and chickens) under natural and experimental conditions. Outcomes from the study support the conclusion that the Cryptosporidium isolates are genetically and biologically distinct from previously described species. We therefore propose them as new species named Cryptosporidium alticolis sp. n. and Cryptosporidium microti sp. n.

Material and methods

Area and specimens studied

From 2014 to 2017 (May to September each year), wild-caught common voles were trapped using snap traps baited with apple and peanut at 16 locations in the Czech Republic (Fig. 1). After trapping, we identified the species, measured body mass (±1 g) and determined the sex of each individual. We estimated the age of each individual using body mass, such that an individual weighing <15 g was considered a juvenile and all other animals were considered adults. Following collection, we dissected each individual and collected a fecal sample from the colon. Fecal samples were stored at 4 °C without fixation. All fecal samples were screened for the presence of Cryptosporidium oocysts using the aniline–carbol–methyl violet (ACMV) staining (Miláček and Vítovec, 1985) followed by microscopic examination at 1000× magnification (light microscope Olympus BX51, Tokyo, Japan). During microscopic examination, we counted oocysts and we quantified the infection intensity as number of oocysts per gram of feces (OPG) according to Kváč et al. (2007).

Fig. 1.

Sampling locations across the study area in the Czech Republic. Sample site numbers indicate the following: (1) Dačice, (2) Výškovice, (3) Náměšť nad Oslavou, (4) Sedlečko u Tábora, (5) Dolní Třebonín, (6) Pelejovice, (7) Radimovice, (8) Budweiss, (9) Bavorovice, (10) Masákova Lhota, (11) Všechov u Tábora, (12) Opatovice, (13) Lovečkovice, (14) Soběslav, (15) Dubovice and (16) Zmišovice.

Molecular characterization

DNA was extracted from 200 mg of feces by bead disruption for 60 s at 5.5 m s−1 using 0.5 mm glass beads in a Fast Prep 24 Instrument (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA) followed by isolation and purification using a commercially available kit in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions (PSP spin stool DNA Kit, Invitek, Stratec, Berlin, Germany). Purified DNA was stored at −20 °C prior to amplification by PCR.

A nested PCR approach was used to amplify a partial region of the small ribosomal subunit rRNA (SSU; ~830 bp; Xiao et al., 1999; Jiang et al., 2005), actin (~1066bp; Sulaiman et al., 2002), Cryptosporidium oocyst wall protein (COWP) (~550 bp; Spano et al., 1997) and 70 kilodalton heat shock protein genes (HSP70; ~ 1950 bp; Sulaiman et al., 2000).

The primary PCR mixtures contained 2 μL of template DNA, 2.5 U of Taq DNA Polymerase (Dream Taq Green DNA Polymerase, Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 0.5× PCR buffer (SSU) or 1× PCR buffer (actin, COWP and HSP70; Thermofisher Scientific), 6 mM MgCl2 (SSU) or 3 mM MgCl2 (actin, COWP and HSP70), 200 μm each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 100 mM each primer and 2 μL non-acetylated bovine serum albumin (BSA; 10 mg ml−1; New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA, USA) in 50 μL reaction volume. The secondary PCR mixtures were similar to those described above for the primary PCR, with the exception that 2 μL of the primary PCR product was used as the template, the MgCl2 concentration was 3 mM and no BSA was used. DNA of C. parvum and molecular grade water were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Secondary PCR products were detected by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis, visualized by ethidium bromide staining and extracted using GenElute™ Gel Extraction Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Purified secondary products were sequenced in both directions with an ABI 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using the secondary PCR primers and the BigDye1 Terminator v3.1 cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems) in 10 μL reactions.

Phylogenetic analysis

The nucleotide sequences of each gene obtained in this study were edited using the ChromasPro 2.4.1. (Technelysium, Pty, Ltd, South Brisbane, Australia) and aligned with each other and with reference sequences from GenBank using MAFFT version 7 online server using the Q-INS-I algorithm (http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/software/). Alignment adjustments were made manually to remove artificial gaps using BioEdit 7.0.5.3 (Hall, 1999). Phylogenetic analyses were performed and the best DNA/protein phylogeny models were selected using the MEGA7 software (Guindon and Gascuel, 2003; Tamura et al., 2013) and Geneious v7.1.7 (http://www.geneious.com). Phylogenetic trees were inferred by maximum likelihood (ML) method, with the substitution model that best fits the alignment selected using the Bayesian information criterion. ML analysis of SSU, actin, COWP and HSP70 alignments was done in the MEGA7 software and concatenated SSU–actin–COWP alignment was done in RAxML v7.2.8 implemented in Geneious. The General Time Reversible model was selected for SSU, actin, HSP70 and concatenated SSU–actin–COWP alignment and the Tamura 3-parameter model was used of COWP alignment. All models were used under an assumption that rate variation among sites was γ distributed with invariant sites.

Bootstrap support for branching was based on 1000 replications. Phylograms were edited for style using CorelDrawX7. Sequences have been deposited in GenBank under the accession numbers (Acc. nos.) MH145308–MH145335.

Origin of specimens for transmission studies

Isolates of C. alticolis sp. n. and C. microti sp. n. were obtained from wild-caught common voles trapped at Dačice and Radimovice, respectively, in the Czech Republic. Oocysts from each species were used to infect a 6-month-old common vole (vole 0). Oocysts from vole 0 were purified using caesium chloride gradient centrifugation (Arrowood and Donaldson, 1996) and used for analysis of oocyst morphometry and to infect other animals (see below).

Transmission studies

We experimentally determined the infectivity and pathogenicity of C. alticolis sp. n. and C. microti sp. n. for 6-month-old common voles, meadow voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus) and yellow-necked mice (Apodemus flavicollis); 2-month-old SCID (severe combined immunodeficiency), BALB/c and C57BL/6J mice (Mus musculus) and brown rats (Rattus norvegicus); and 3-day-old chickens (Gallus gallus f. domestica). Common voles and yellow-necked mice used for infectivity studies were obtained from captive colonies maintained at the Institute of Parasitology, Biology Centre of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Česke Budějovice, Czech Republic. Laboratory (i.e. house mouse) mice and rats were purchased from Charles River Laboratories, Sulzfeld, Germany. Chickens originated from International Testing of Poultry, Ústrašice, Tábor, Czech Republic. Meadow voles were obtained from a captive colony maintained at Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts, USA and used in transmission studies at North Dakota State University, USA. All other experiments were performed at the Biology Centre of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic. In determining infectivity and pathogenicity, we used five individuals from each species/group. A week prior to inoculation, fecal samples from all individuals were screened daily for the presence of Cryptosporidium oocysts and specific DNA of Cryptosporidium spp. using parasitological and molecular tools (SSU) as described above. Individuals were housed separately in plastic cages with sterilized bedding and supplied with a sterilized diet and water ad libitum. Each animal was inoculated orally by gavage with 100 000 purified oocysts suspended in 200 μL of distilled water. Fecal samples from each individual were screened daily for the presence of Cryptosporidium oocysts using ACMV staining and specific DNA using nested PCR targeting the SSU gene. At least three amplicons of each target gene were sequenced directly in both directions from each infected individual.

All experiments were terminated 30 days post-infection (DPI). Course of infection indicators, including fecal consistency, fecal colour and infection intensity, was examined.

Histopathological and scanning electron microscopy examinations

The gastrointestinal tract of one animal from each group was examined following necropsy at 6 DPI (this time was selected based on preliminary results; data not shown). The entire small and large intestine was divided into 1 cm sections and samples were processed for histology, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and PCR/sequencing. Specimens for histology were fixed in 4% buffered formalin and processed by the usual paraffin method. Histological sections (5 μm) were stained with haematoxylin and eosin and periodic acid–Schiff stains. The specimens for SEM were fixed overnight at 4 °C in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, washed three times for 15 min in the same buffer, post-fixed in 2% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M phosphate buffer for 2 h at room temperature and finally washed three times for 15 min in the same buffer. After dehydration in a graded acetone series, specimens were dried using the critical point technique, coated with gold and examined using a JEOL JSM-7401F-FE SEM.

Oocyst morphometry

Oocysts of C. alticolis sp. n. and C. microti sp. n. were examined using differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy, ACMV staining and fluorescence microscopy (Olympus IX70, Tokyo, Japan) following labelling with genus-specific FITC-conjugated antibodies (Cryptosporidium IF Test, Crypto Cell, Medac, Wedel, Germany). Morphometry of oocysts was determined using digital analysis of images (M.I.C. Quick Photo Pro v.3.1 software; Promicra, s.r.o., Praha, Czech Republic) collected using an Olympus Digital Colour Camera DP73. Length and width of 50 oocysts of each isolate were measured under DIC at 1000× magnification and the ratio of the length/width of each oocyst was calculated. The mean and standard deviation (S.D.) of length, width and ratio of the length/width of oocysts of each isolate were calculated.

Animal care

Animal caretakers wore disposable coveralls, shoe covers and gloves whenever entering the rooms where animals were housed. All wood-chip bedding, feces and disposable protective clothing were sealed in plastic bags, removed from the buildings and incinerated at the end of the study.

Statistical analysis

Prevalence was calculated by dividing the number of positive individuals by the total number of individuals sampled. Differences in Cryptosporidium prevalence were determined by χ2 analysis using a 5% significance level. The hypothesis tested in the analysis of oocyst morphometry was that two-dimensional mean vectors of measurement are the same in the two populations being compared. Hotelling’s T2 test was used to test the null hypothesis. Analyses were performed using program Epi Info (TM) 7.1.1.14 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, GA, USA) and R 3.5.0. (https://www.r-project.org/).

Results

Prevalence and infection intensity of Cryptosporidium

Out of 328 fecal samples from wild-caught common voles, 19 (5.8%) were microscopically positive for the presence of oocysts of Cryptosporidium sp. and 74 (22.6%) were positive for the presence of specific DNA of Cryptosporidium spp. (Table 1). All microscopically positive samples were also positive using PCR. Positive voles were trapped at 11 out of 16 localities (Table 2). There was no difference (χ2 = 0.0153; D.F. = 1; P = 0.9016) in the prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp. in males (22.0%; 41/186) and females (23.2%; 33/142). Similarly, the prevalence did not differ (χ2 = 0.3254; D.F.= 1; P = 0.5684) between juvenile (25.7%; 19/74) and adult voles (21.7%; 55/254; Table 2). Infection intensity, which ranged from 4000 to 42 000 OPG, did not differ (P = 0.1773) between males (2000–36 000 with mean 15 000 OPG) and females (4000–42 000 with mean 20 000 OPG). None of the trapped voles had diarrhoea.

Table 1.

Number of wild-caught common voles positive for Cryptosporidium by PCR and microscopy, by sex and age

| Sex | Age | n | PCR positive | Microscopically positive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | J | 29 | 9 | 3 |

| A | 113 | 24 | 3 | |

| Male | J | 45 | 10 | 3 |

| A | 141 | 31 | 10 | |

| Total | 328 | 74 | 19 |

J, juvenile; A, adult.

Table 2.

Cryptosporidium spp. in wild common voles (Microtus arvalis)

| Isolate ID | Location (number of screened samples/positive) | Microscopical positivity (OPG) | Genotyping at the gene loci (GenBank Acc. No. used in the phylogenetic trees) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSU | Actin | COWP | HSP70 | |||

| 19608a | Dačice (97/25) | Yes (4000) | C. microti | C. microti | ||

| 19612a | No | C. microti | C. microti | |||

| 19615 | No | C. microti | C. microti | |||

| 19618a | No | C. microti | C. microti | C. microti | ||

| 20055a | No | C. microti | C. microti | C. microti | ||

| 20057 | Yes (4000) | C. microti | C. microti | |||

| 20059 | Yes (18 000) | vole VII | vole VII | vole VII | ||

| 20063 | No | vole V | vole V | vole V | ||

| 20065a | Yes (6000) | C. alticolis (KY 644657) | C. alticolis | C. alticolis | C. alticolis | |

| 23407 | No | C. microti | C. microti | |||

| 23408 | No | C. microti | C. microti | |||

| 23409b | No | vole V (MH145331) | vole V (MH145311) | vole V (MH145319) | vole V (MH145325) | |

| 23410 | No | C. microti | C. microti | |||

| 23390 | No | vole V | vole V | |||

| 22731 | Yes (8000) | C. alticolis | C. alticolis | C. alticolis | ||

| 23392b | No | vole VII (MH145333) | vole VII (MH145313) | vole VII (MH145321) | vole VII (MH145327) | |

| 23393 | No | C. microti | C. microti | |||

| 23250 | No | C. microti | C. microti | C. microti | ||

| 23251 | No | C. microti | C. microti | |||

| 23231 | No | C. microti | C. microti | |||

| 23111b | Yes (2000) | C. alticolis (MH145330) | C. alticolis (MH145310) | C. alticolis (MH145318) | C. alticolis (MH145324) | |

| 23112 | No | C. alticolis | C. alticolis | C. alticolis | ||

| 23746a | Yes (30 000) | C. microti | C. microti | C. microti | C. microti | |

| 23747 | No | C. alticolis | C. alticolis | |||

| 23748a | No | C. microti | C. microti | C. microti | C. microti | |

| 20062a,b | Výškovice (3/1) | No | vole III (MH145329, KY644593) | vole III (MH145309) | vole III (MH145317) | |

| 23750a | Náměšť: nad Oslavou (40/8) | No | C. microti | C. microti | ||

| 23400a,b | No | vole VI (MH 145332) | vole VI (MH 145312) | vole VI (MH 145320) | vole VI (MH 145326) | |

| 23405a | No | vole VI | vole VI | |||

| 28082b | Yes (16 000) | vole IV (MH145335) | vole IV (MH145315) | |||

| 30906 | No | vole IV | vole IV | |||

| 30908 | No | vole IV | vole IV | |||

| 30909b | No | vole II (MH145334) | vole II (MH145314) | vole II (MH145322) | ||

| 30928 | No | C. microti | C. microti | |||

| 22339 | Sedlečko u Tábora (35/2) | No | C. microti | |||

| 22336 | No | C. microti | ||||

| 21146 | Dolní Třebonín (32/8) | Yes (36 000) | C. microti | C. microti | ||

| 22352 | No | C. microti | C. microti | C. microti | ||

| 23115a | No | C. microti | C. microti | C. microti | ||

| 23236a | No | C. microti (KY644604) | C. microti (KY657294) | C. microti | ||

| 23743a | No | C. microti | C. microti | C. microti | ||

| 24128a | Yes (24 000) | vole VI | vole VI | vole VI | ||

| 24129a | No | vole VI (KY644632) | vole VI | vole VI | ||

| 25643a | No | C. microti | C. microti | C. microti | ||

| 24514 | Pelejovice (37/2) | No | C. microti | C. microti | C. microti | |

| 24916a | No | vole V (KY644670) | vole V | |||

| 24919a | Radimovice (18/7) | No | C. microti | C. microti | ||

| 24922a | No | C. microti | C. microti | C. microti | C. microti | |

| 24923b | No | C. microti (MH 145328) | C. microti (MH145308) | C. microti (MH145316) | C. microti (MH145323) | |

| 24924 | No | C. microti | C. microti | |||

| 24926a | No | C. microti | C. microti | C. microti | C. microti | |

| 25163a | No | C. microti | C. microti | C. microti | C. microti | |

| 25164a | No | C. microti | C. microti | C. microti | C. microti | |

| 28061 | České Budějovice (2/1) | No | vole V | |||

| 28315 | Masákova Lhota (18/7) | No | C. alticolis | C. alticolis | C. alticolis | |

| 28317 | Yes (10 000) | C. microti | C. microti | C. microti | ||

| 28566 | Yes (4000) | C. microti | C. microti | |||

| 28567 | No | vole VI | vole VI | |||

| 28665 | No | C. microti | C. microti | |||

| 28667 | No | C. microti | C. microti | |||

| 29936 | No | C. microti | C. microti | C. microti | ||

| 28422 | Všechov u Tábora (30/12) | No | vole VII | vole VII | ||

| 28423 | Yes (42 000) | C. microti | C. microti | C. microti | ||

| 28425 | No | C. alticolis | C. alticolis | |||

| 28428 | No | vole VII | vole VII | |||

| 28429 | Yes (8000) | C. microti | C. microti | |||

| 28539 | Yes (14 000) | C. microti | C. microti | C. microti | ||

| 28540 | Yes (32 000) | C. microti | C. microti | |||

| 28541 | Yes (18 000) | vole VII | vole VII | |||

| 28543 | No | C. microti | C. microti | C. microti | ||

| 28545 | Yes (6000) | C. microti | C. microti | |||

| 28546 | No | C. microti | C. microti | |||

| 28549 | Yes (8000) | C. microti | C. microti | |||

| 30904 | Opatovice (4/1) | No | C. microti | C. microti | C. microti | |

Isolates were characterized by microscopy, including infection intensity expressed as number of oocyst per gram of feces (OPG), and PCR analysis of the small ribosomal subunit rRNA (SSU), actin, Cryptosporidium oocyst wall protein (COWP) and 70 kDa heat shock protein (HSP70) genes. Only localities where Cryptosporidium-positive animals were trapped are shown.

Sequences of SSU and actin previously obtained in the study of Stenger et al. (2018).

Sequence of isolates used in phylogeny trees.

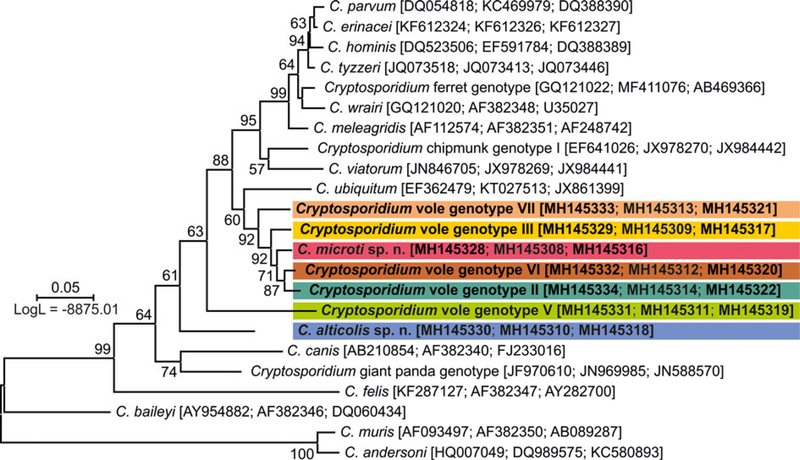

Out of 74 voles positive for Cryptosporidium, 74,71,33 and 14 were genotyped by sequence analysis of SSU, actin, COWP and HSP70 genes, respectively (Table 2, Fig. 2 and online Supplementary Figs S1–S4). The remaining positive samples yielded sequences of insufficient quality to include in analyses (three actin sequences) or failed to amplify at COWP (n = 41) and HSP70 (n = 60) loci.

Fig. 2.

A maximum likelihood (ML) tree based on concatenated small subunit rRNA (SSU), actin and Cryptosporidium oocyst wall protein (COWP) gene sequences. A representative of each SSU, actin and COWP species/genotype from wild-caught common voles from this study is highlighted in bold. GenBank accession numbers are shown in parenthesis after the isolate identifier. Numbers at the nodes represent the bootstrap values gaining more than 50% support. Branch length scale bar indicates the number of substitutions per site.

Sequence analysis revealed the presence of eight genotypes of Cryptosporidium, of which two are described here as new species (Table 2). ML trees inferred from sequences of SSU, actin, COWP and HSP70 genes individually or SSU, actin and COWP in concatenation formed three major phylogenetic groups (Fig. 2 and online Supplementary Figs S1–S4). Group 1 included C. microti sp. n. and Cryptosporidium vole genotypes II, III, VI and VII. Cryptosporidium microti (n = 47) was identical to Cryptosporidium sp. isolate 19608-Miar-EU previously recovered from a wild-caught common vole in the Czech Republic [Acc. No. KY657290] and was closely related to Cryptosporidium muskrat genotype II [Acc. No. AY737571], Cryptosporidium sp. isolate 1857-Mipe-NA from a wild-caught meadow vole [Acc. No. KY644574] and Cryptosporidium sp. isolate 1544-Pero-NA from a wild-caught Peromyscus mouse [Acc. No. KY644565] in the USA, sharing 99.2%, 98.8% and 98.6% sequence identity, respectively.

Cryptosporidium vole genotype III (n = 1) was identical to Cryptosporidium sp. isolate 20062-Miar-EU from a wild-caught common vole in the Czech Republic (Acc. No. KY644593) and clustered with Cryptosporidium sp. isolate 10482-Mygl-EU from a wild-caught bank vole (Acc. No. KY644595) and Cryptosporidium sp. isolate 2035-Myga-NA from a wild-caught Southern red-backed vole (Acc. No. KY644592) in Slovakia and the USA, respectively, sharing 99.8 and 99.5% sequence identity.

Cryptosporidium vole genotype VI (n = 5) was identical to Cryptosporidium sp. isolate 24129-Miar-EU from a wild-caught common vole in the Czech Republic (Acc. No. KY644632) and clustered with Cryptosporidium vole genotype II (n =1) from the present study (Acc. No. MH145334), sharing 99.1% sequence identity. Cryptosporidium vole genotype VII (n = 5), a genotype that was first identified in this study, clustered with the Cryptosporidium vole genotype (Acc. No. EF641020) and Cryptosporidium sp. isolate 1947-Mipe-NA (Acc. No. KY644626), both from wild-caught meadow voles in the USA, sharing 98.9 and 98.5% sequence identity, respectively. C. alticolis sp. n. (n = 7), the only member of group 2, was identical to Cryptosporidium sp. isolate 20065-Miar-EU from a wild-caught common vole in the Czech Republic (Acc. No. KY644657), and clustered with Cryptosporidium sp. isolate 2333-Pero-NA from a wild-caught meadow vole in the USA (Acc. No. KY644655) and Cryptosporidium sp. isolate Mrb001 from a grey red-backed vole in Japan (Acc. No. AB477098), sharing 97.3 and 97.5% sequence identity, respectively.

Group 3 comprised Cryptosporidium vole genotype IV (n = 3) and vole genotype V (n = 5). Cryptosporidium genotype vole V was identical to Cryptosporidium sp. isolate 24916-Miar-EU from a wild-caught common vole in the Czech Republic (Acc. No. KY644670) and formed a sister group with muskrat genotype I (Acc. No. EF641013) and Cryptosporidium sp. isolate 1962-Mipe-NA from a wild-caught meadow vole (Acc. No. KY644685), both in the USA, sharing 98.1 and 98.0% sequence identity, respectively. Cryptosporidium vole genotype IV, which was reported for the first time in this study, clustered outside of this group.

Based on evidence that they are genetically and biologically distinct from known Cryptosporidium species, we describe C. alticolis sp. n. and C. microti sp. n. as new species of the genus Cryptosporidium. Descriptions of C. alticolis sp. n. and C. microti sp. n. follow.

Cryptosporidium alticolis sp. n.

Prevalence and infection intensity.

Seven voles (2.1%) from three localities had DNA of C. alticolis sp. n. detectable by PCR, of which three had oocysts that were detectable by microscopy with an infection intensity of 2000–8000 OPG (Table 2).

Experimental transmission.

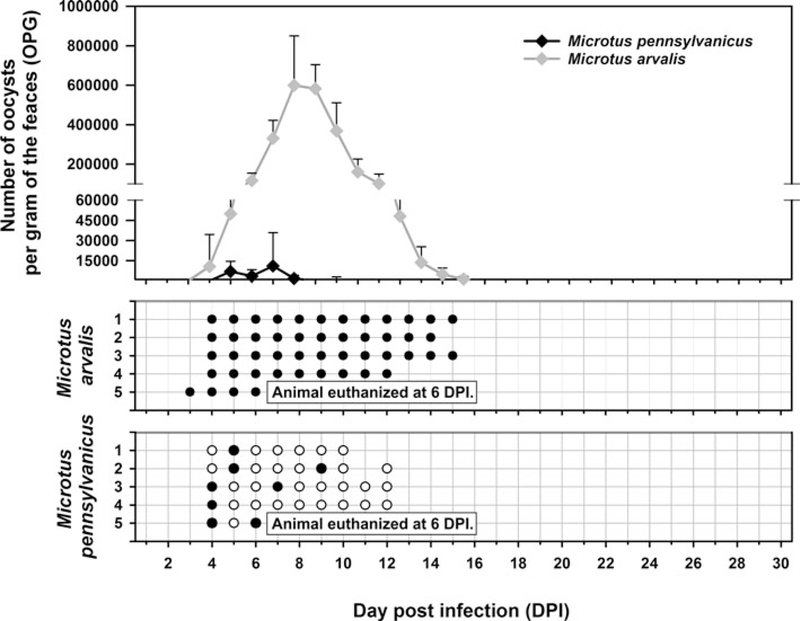

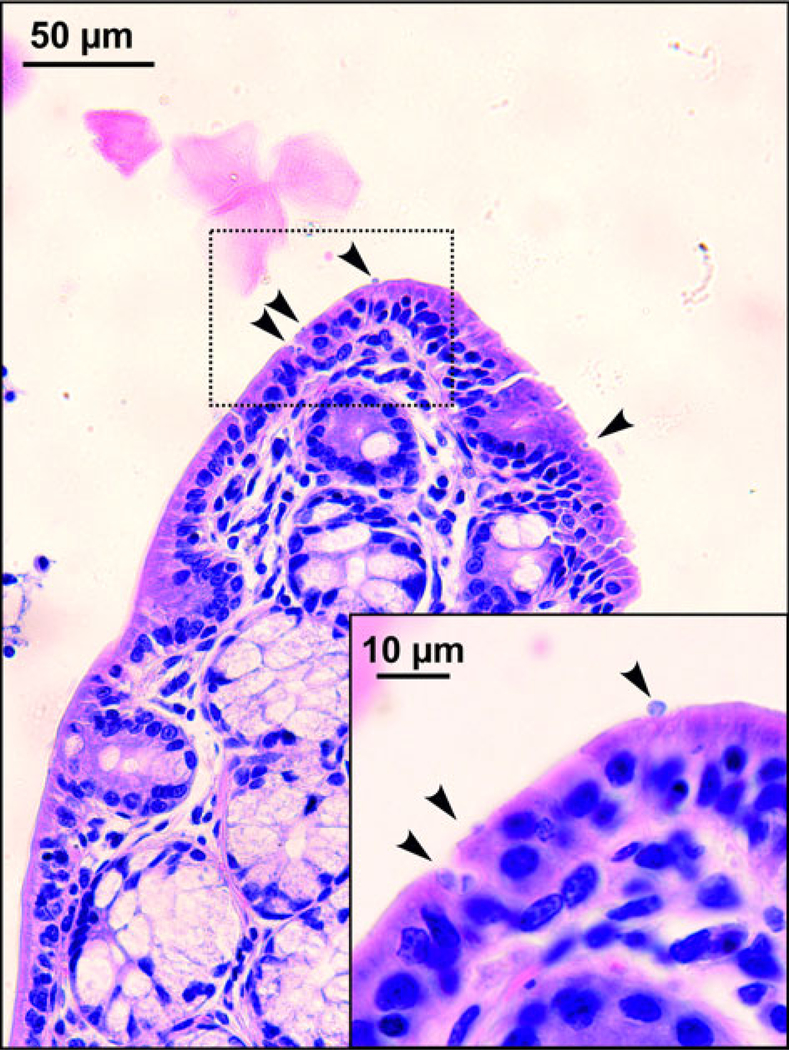

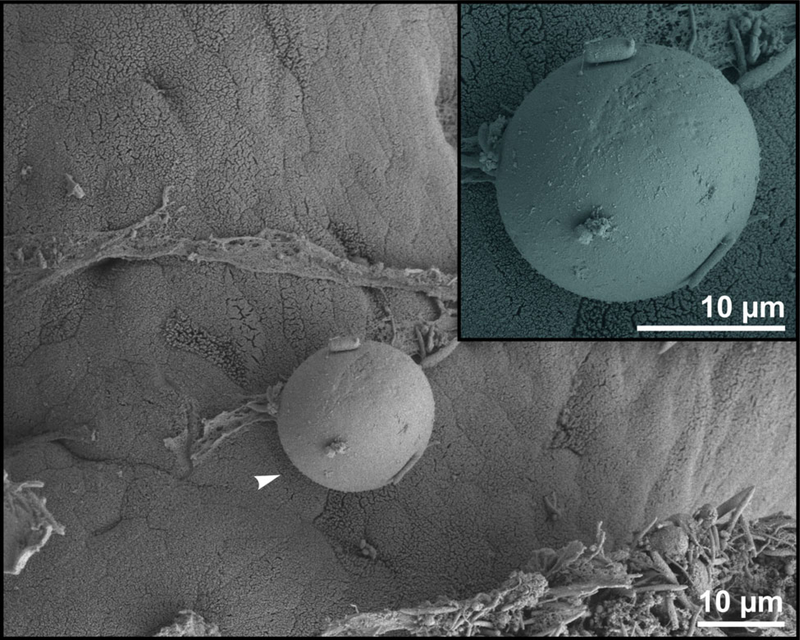

Oocysts of C. alticolis sp. n. from naturally infected common voles were infectious for common and meadow voles, but not for yellow-necked mice, SCID mice, BALB/c mice, C57BL/6J mice, brown rats or chickens. The prepatent period of C. alticolis sp. n. in common and meadow voles was 3–4 DPI (Fig. 3). Whereas common voles shed oocysts of C. alticolis sp. n. continuously during the patent period (12–15 DPI), meadow voles shed oocysts sporadically up to 12 DPI (Fig. 3). The infection intensity of C. alticolis sp. n. in common voles (2000–1000 000 OPG) was higher than in meadow voles (2000–50 000 OPG). No macroscopical changes were observed in the gastrointestinal tract of common or meadow voles infected with C. alticolis sp. n. and the surface epithelium remained intact. DNA of C. alticolis sp. n. was detected throughout the small and large intestine of common and meadow voles; however, endogenous developmental stages were detected only in the jejunum and ileum by histology and electron microscopy (Figs 4 and 5). Cryptosporidium alticolis sp. n. was not detected in the stomach and other organs (liver, pancreas, kidneys, lungs and spleen). None of the experimentally infected common or meadow voles were diarrhoeic. The lamina propria in the jejunum and ileum was slightly oedematous with occasional dilatation of lymphatic vessels (data not shown). Sequences of SSU, actin, COWP and HSP70 genes from experimentally infected hosts shared 100% identity with the isolate used in the inoculum.

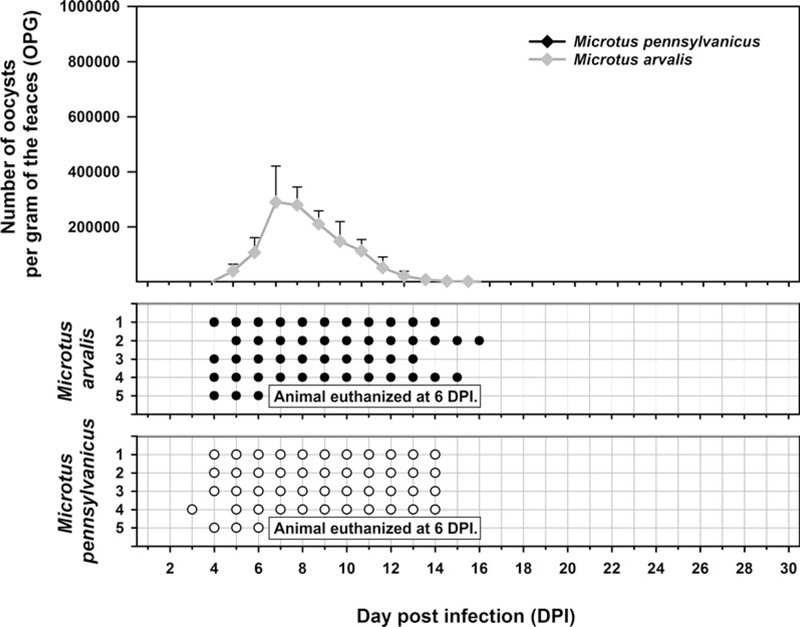

Fig. 3.

Course of infection of Cryptosporidium alticolis sp. n. in experimentally infected common voles (Microtus arvalis) and in meadow voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus) based on coprological and molecular examination of feces. Any circles indicate detection of specific DNA, black circle indicates microscopic detection of oocysts.

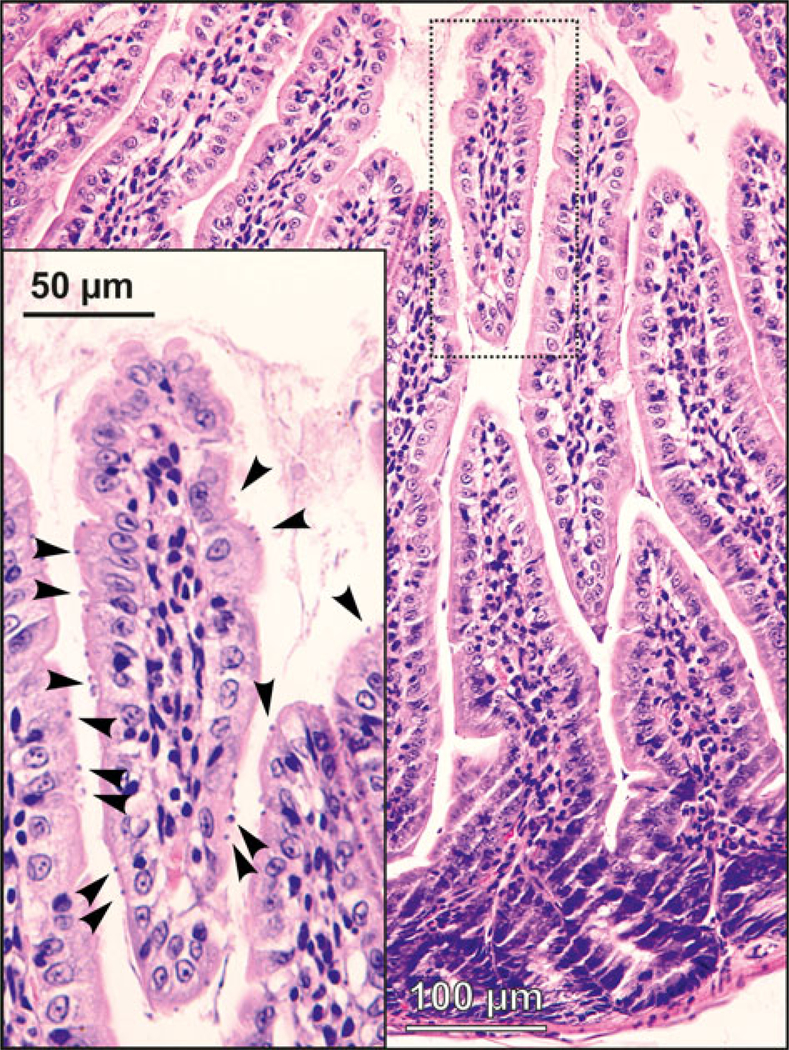

Fig. 4.

Developmental stages (arrowheads) of Cryptosporidium alticolis sp. n. in mucosal glandular epithelium from the duodenum of an experimentally infected common vole (Microtus arvalis). Bar included in each picture.

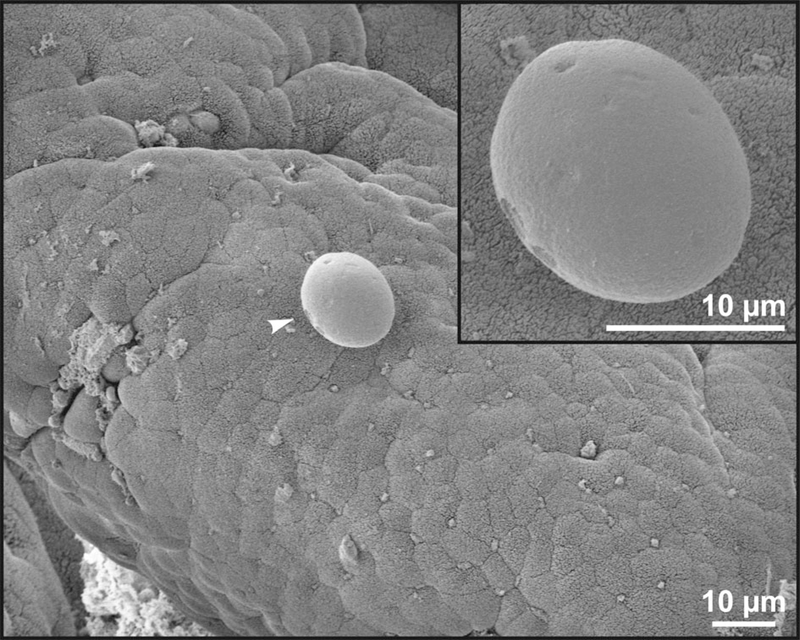

Fig. 5.

Scanning electron photomicrograph of the jejunal epithelium of an experimentally infected common vole (Microtus arvalis). Attached developmental stage of Cryptosporidium alticolis sp. n. (arrowhead; detail in the upper right corner).

Taxonomic summary

ZooBank number for species: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:D12C78AA-222E-4E07-A7CE-51AA6A747BC6

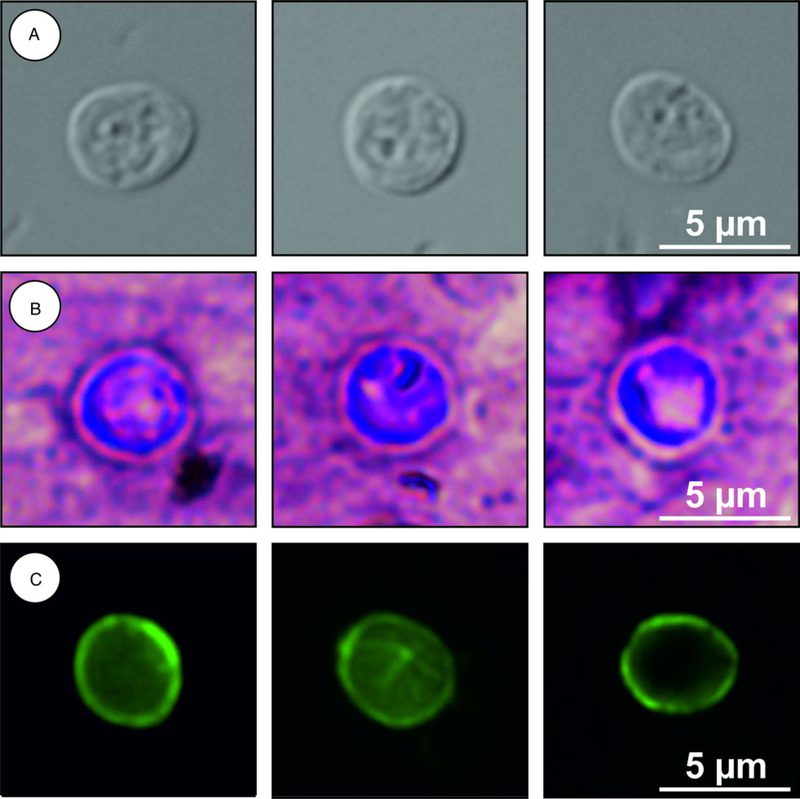

Description: Oocysts are shed fully sporulated with four sporozoites and an oocyst residuum. Sporulated oocysts (n = 50) measure 4.9–5.7 μm (mean ± S.D. = 5.4 ± 0.2 μm) × 4.6–5.2 μm (mean ± S.D. = 4.9 ± 0.2 , μm) with a length/width ratio of 1.00–1.20 (mean ± S.D. = 1.10 ± 0.05) (Fig. 6). Morphology and morphometry of other developmental stages are unknown.

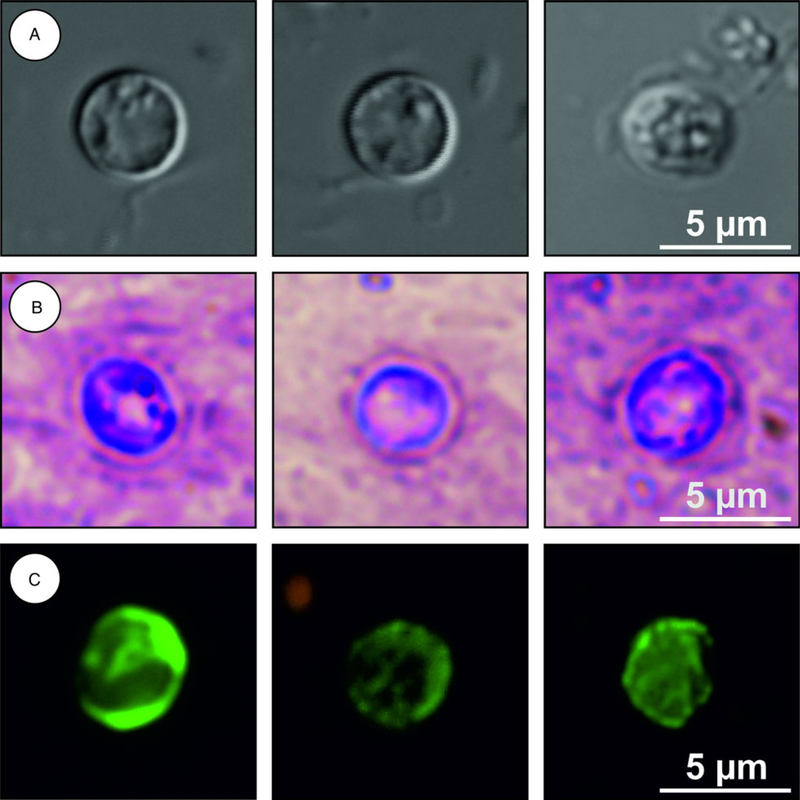

Fig. 6.

Cryptosporidium alticolis sp. n. oocysts visualized in various preparations: (A) differential interference contrast microscopy and stained by (B) aniline-carbol-methyl violet and (C) anti-Cryptosporidium FITC-conjugated antibody. Bar included in each picture.

Type host: common vole (M. arvalis)

Type locality: Dačice (Czech Republic)

Other localities: Masákova Lhota and Všechov (Czech Republic)

Site of infection: jejunum and ileum (Figs 4 and 5)

Distribution: Czech Republic

Type material/hapanotype: Tissue samples in 10% formaldehyde and histological sections of infected jejunum (nos. 174/2016, 175/2016, 176/2016 and 177/2016) and ileum (nos. 178/2016 and 179/2016); genomic DNA isolated from fecal samples of naturally (isolation no. 23111) and experimentally (isolation no. 27124) infected M. arvalis; genomic DNA isolated from jejunal and ileal tissue of experimentally infected M. arvalis (isolation nos. 27035 and 27037, respectively); digital photomicrographs (nos. DIC 1–13/23111, MV 1–11/23111, IF 1–9/23111, HI 1–3/27124 and SEM 1–3/27124) and fecal smear slides with oocysts stained by ACMV staining from experimentally infected M. arvalis (nos. 27124/3, 27124/4, 27124/5 and 27124/6). Specimens deposited at the Institute of Parasitology, Biology Centre of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Czech Republic.

Reference sequences: Partial sequences of SSU, actin, COWP and HSP70 genes were deposited at GenBank under Acc. Nos. MH145330, MH145310, MH145318 and MH145324, respectively.

Etymology: The species name alticolis is derived from the Latin noun ‘alticola’ (meaning a vole).

Differential diagnosis: Oocysts of C. alticolis are larger than those of C. microti (P = 0.001), have similar ACMV staining to other species of Cryptosporidium and cross-react with antibodies developed primarily for C. parvum (Fig. 6). It can be differentiated genetically from other Cryptosporidium spp. based on sequences of SSU, actin, COWP and HSP70 genes. Endogenous development of C. alticolis sp. n. takes place in the small intestine, whereas C. microti develops in the large intestine.

Cryptosporidium microti sp. n.

Prevalence.

Forty-seven wild-caught common voles (14.3%) from nine localities were positive for C. microti sp. n. by PCR, of which 12 had oocysts detectable by microscopy. The infection intensity ranged from 4000 to 42 000 OPG.

Experimental transmission.

Oocysts of C. microti sp. n. from naturally infected common voles were infectious for common and meadow voles, but not for yellow-necked mice, SCID mice, BALB/c mice, C57BL/6J mice, brown rats or chickens. Common voles shed C. microti sp. n. from 4 to 16 DPI, with oocysts detectable by microscopy throughout this period. The infection intensity ranged from 2000 to 430 000 OPG with maximum shedding at 6–7 DPI (Fig. 7). In meadow voles, DNA of C. microti sp. n. was detected from 4 to 14 DPI; however, oocysts were not detectable by microscopy at any time during the patent period.

Fig. 7.

Course of infection of Cryptosporidium microti sp. n. in experimentally infected common voles (Microtus arvalis) and in meadow voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus) based on coprological and molecular examination of feces. Any circles indicate detection of specific DNA, black circle indicates microscopic detection of oocysts.

Sequences of SSU, actin, COWP and HSP70 genes from experimentally infected hosts shared 100% identity with the isolate used in the inoculum. Specific DNA of C. microti sp. n. was found exclusively in the caecum and colon of common and meadow voles. Endogenous developmental stages were detected in the caecum and colon of the common vole (Figs 8 and 9), but were not detected in the meadow vole. Infections were not associated with macroscopical or pathological changes in the digestive tract of common or meadow voles and these animals showed no signs of diarrhoea.

Fig. 8.

Developmental stages (arrowheads) of Cryptosporidium microti sp. n. in mucosal glandular epithelium from the colon of an experimentally infected common vole (Microtus arvalis). Bar included in each picture.

Fig. 9.

Scanning electron photomicrograph of the colon epithelium of a common vole (Microtus arvalis). Attached developmental stage of Cryptosporidium microti sp. n. (arrowhead; detail in the upper right corner).

Taxonomic summary

ZooBank number for species: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:4FD6136C-3932-4881-BE49-4714A5AB488A

Description: Oocysts are shed fully sporulated with four sporozoites and an oocyst residuum. Sporulated oocysts (n = 50) measure 3.9–4.7 μm (mean ± S.D. = 4.3 ± 0.1 μm) × 3.8–4.4 μm (mean ± S.D. = 4.1 ± 0.1 μm) with length/width ratio of 1.00–1.06 (mean ± S.D. = 1.03 ± 0.02) (Fig. 10). Morphology and morphometry of other developmental stages are unknown.

Fig. 10.

Cryptosporidium alticolis sp. n. oocysts visualized in various preparations: (A) differential interference contrast microscopy and stained by (B) aniline-carbol-methyl violet and (C) anti-Cryptosporidium FITC-conjugated antibody. Bar included in each picture.

Type host: common vole (M. arvalis)

Type locality: Radimovice (Czech Republic)

Other localities: Dačice, Zňatky, Sedlečko, Dolní Třebonin, Pelejovice, Masakova Lhota, Všechov and Opatovice (Czech Republic)

Site of infection: caecum and colon (Figs 8 and 9)

Distribution: Czech Republic

Type material/hapanotype: Tissue samples in 10% formaldehyde and histological sections of infected caecum (nos. 97/2016 and 98/2016) and colon (nos. 99/2016 and 100/2016), genomic DNA isolated from fecal samples of naturally (isolation no. 24923) and experimentally (isolation no. 28063) infected M. arvalis; genomic DNA isolated from ceacal and colonical tissue of experimentally infected M. arvalis (isolation nos. 29751 and 29753, respectively); digital photomicrographs (nos. DIC 1–11/24923, MV 1–9/24923, IF 1–9/24923, HI 1–3/28063 and SEM 1–3/28063) and fecal smear slides with oocysts stained by ACMV staining from experimentally infected M. arvalis (nos. 28063/3, 28063/4, 28063/5 and 28063/6). Specimens deposited at the Institute of Parasitology, Biology Centre of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Czech Republic.

Reference sequences: Partial sequences of SSU, actin, COWP and HSP70 genes were deposited at GenBank under Acc. Nos. MH145328, MH145308, MH145316 and MH145323, respectively.

Etymology: The species name microti is derived from the Latin noun ‘microtus’ (meaning a vole).

Differential diagnosis: Oocysts of C. microti sp. n. are smaller than those of C. alticolis sp. n. (P = 0.001), have similar ACMV staining to other species of Cryptosporidium and cross-react with antibodies developed primarily for C. parvum (Fig. 10). It can be differentiated genetically from other Cryptosporidium spp. based on sequences of SSU, actin, COWP and HSP70 genes. Endogenous development of C. microti sp. n. takes place in the large intestine, whereas C. alticolis sp. n. develops in the small intestine.

Discussion

This and other genotyping studies have shown that voles host several Cryptosporidium species and genotypes that appear to be host specific and not infectious for humans, but they rarely host C. parvum (Feng et al., 2007; Stenger et al., 2018; Ziegler et al., 2007a, 2007b). The finding that oocysts of C. alticolis sp. n. and C. microti sp. n. are indistinguishable from oocysts of C. parvum suggests that earlier detections of C. parvum, which were not supported by genotyping data, were misidentifications. Oocyst size is generally only useful for differentiating intestinal (smaller and rounder) and gastric (larger and more oval) species of Cryptosporidium (Ryan and Xiao, 2014).

Cryptosporidium microti sp. n. and Cryptosporidium vole genotypes II, III, VI and VII clustered as part of a large heterogeneous group in ML trees. This is generally consistent with the report by Stenger et al. (2018) that Cryptosporidium genotypes from voles in the Europe and North America formed between three and four phylogenetic groups in ML trees.

Cryptosporidium alticolis sp. n. and C. microti sp. n. are genetically distinct from other known species of Cryptosporidium. Cryptosporidium alticolis sp. n. shares 95.2, 94.7 and 94.3% sequence identity, respectively, with C. canis, C. suis and C. parvum at the SSU locus; 87.9, 90.5 and 89.7%, respectively, at the actin locus; and 84.5, 91.2 and 90.5%, respectively, at the HSP70 locus. At the COWP locus, C. alticolis sp. n. shared 88.1 and 89.9% sequence identity, respectively, with C. canis and C. parvum. Cryptosporidium microti sp. n. shared 95.5, 98.8 and 96.4% sequence identity, respectively, with C. canis, C. suis and C. parvum at the SSU locus; 85.6, 91.6 and 90.5%, respectively, at the actin locus; and 84.2, 93.1 and 92.6%, respectively, at the HSP70 locus. At the COWP locus, C. microti sp. n. shared 86.7 and 91.5% sequence identity, respectively, with C. canis and C. parvum. In comparison, C. hominis and C. parvum share 98–99% identity and C. muris and C. andersoni share 96–99% identity at these loci.

The prevalence of Cryptosporidium in voles ranges from 1 to 100% (Laakkonen et al., 1994; Perz and Le Blancq, 2001; Bajer et al., 2002, 2003; Zhou et al., 2004). The prevalence in wild-caught common voles in the present study (23%) was greater than the 14% reported by Stenger et al. (2018) using similar detection methods, and much lower than the 62–73% reported by Bajer et al. (2002) and Bajer (2008) using microscopic detection, a method that is less sensitive than PCR. The prevalence of Cryptosporidium can be affected by factors such as age, season, population density, location, weather and climate, diet and water consumption (Nichols et al., 2014).

Cryptosporidium microti sp. n. dominated at most locations in this study. Mixed infections were not detected, but they cannot be ruled out because the methods used were not effective at detecting multi-species infections. Microscopy cannot differentiate among species with similar sized oocysts and PCR preferentially amplifies DNA from the dominant species/genotype (Santín and Zarlenga, 2009; Jeníková et al., 2011; Ma et al., 2014; Qi et al, 2015).

Cryptosporidium alticolis sp. n. infects the small intestine, which is similar to most intestinal Cryptosporidium spp. of mammals (Ryan and Xiao, 2014). In contrast, C. microti is only the third species, after C. suis in pigs and C. oculltus in rats, reported to infect the colon (Ryan et al., 2004; Vítovec et al., 2006; Kváč et al., 2018). Similar to C. oculltus (Kváč et al., 2018), C. microti sp. n. localizes to the mucosal surface in the large intestine. In contrast, C. suis predominates in the glandular epithelium of the submucosal colonic lymphoglandular complexes in pigs (Vítovec et al., 2006).

Neither C. alticolis sp. n. nor C. microti sp. n. developed clinical signs in common voles or meadow voles under experimental conditions in the present study. This is consistent with the reports that wild animals rarely display signs of clinical cryptosporidiosis (Sturdee et al., 1999; Hikosaka and Nakai, 2005; Castro-Hermida et al., 2011; Němejc et al., 2012; Čondlová et al., 2018).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support. This study was funded by Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic (LTAUSA17165), the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (1R15AI122152-01A1), Grant Agency of University of South Bohemia (098/2016/Z and 002/2016/Z) and supported by MEYS CR (LM2015062 Czech-BioImaging). We thank Annaliese Beery, Jennifer Christensen, Nancy Owen and Karen Swiecanski of Smith College for providing meadow voles and for assistance with transporting voles to North Dakota State University for the study.

Ethical standards. The research was conducted under ethical protocols approved by the Institute of Parasitology, Biology Centre and Central Commission for Animal Welfare, Czech Republic (protocol nos. 071/2010 and 114/2013) and Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee North Dakota State University, ND, USA (protocol no. A18014).

Footnotes

Supplementary material. The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182018001142

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

- Arrowood MJ and Donaldson K (1996) Improved purification methods for calf-derived Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts using discontinuous sucrose and caesium chloride gradients. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 43, 89S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajer A (2008) Cryptosporidium and Giardia spp. infections in humans, animals and the environment in Poland. Parasitology Research 104, 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajer A, Bednarska M, Pawelczyk A, Behnke JM, Gilbert FS and Sinski E (2002) Prevalence and abundance of Cryptosporidium parvum and Giardia spp. in wild rural rodents from the Mazury Lake District region of Poland. Parasitology 125, 21–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajer A, Caccio S, Bednarska M, Behnke JM, Pieniazek NJ and Sinski E (2003) Preliminary molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium parvum isolates of wildlife rodents from Poland. Journal of Parasitology 89, 1053–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baneth G, Thamsborg SM, Otranto D, Guillot J, Blaga R, Deplazes P and Solano-Gallego L (2016) Major parasitic zoonoses associated with dogs and cats in Europe. Journal of Comparative Pathology 155, S54–S74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bednarska M, Bajer A, Sinski E, Girouard AS, Tamang L and Graczyk TK (2007) Fluorescent in situ hybridization as a tool to retrospectively identify Cryptosporidium parvum and Giardia lamblia in samples from terrestrial mammalian wildlife. Parasitology Research 100, 455–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull SA, Chalmers RM, Sturdee AP and Healing TD (1998) A survey of Cryptosporidium species in Skomer bank voles (Clethrionomys glareolus skomerensis). Journal of Zoology 244, 119–122. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Hermida JA, García-Presedo I, González-Warleta M and Mezo M (2011) Prevalence of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) and wild boars (Sus scrofa) in Galicia (NW, Spain). Veterinary Parasitology 179, 216–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers RM, Sturdee AP, Bull SA, Miller A and Wright SE (1997) The prevalence of Cryptosporidium parvum and C. muris in Mus domesticus, Apodemus sylvaticus and Clethrionomys glareolus in an agricultural system. Parasitology Research 83, 478–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Checkley W, White AC Jr, Jaganath D, Arrowood MJ, Chalmers RM, Chen XM, Fayer R, Griffiths JK, Guerrant RL, Hedstrom L, Huston CD, Kotloff KL, Kang G, Mead JR, Miller M, Petri WA Jr, Priest JW, Roos DS, Striepen B, Thompson RC, Ward HD, Van Voorhis WA, Xiao L, Zhu G and Houpt ER (2015) A review of the global burden, novel diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccine targets for cryptosporidium. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 15, 85–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Čondlová S, Horčičková M, Sak B, Kvétoňová D, Hlásková L, Konečný R, Stanko M, McEvoy J and Kváč M (2018) Cryptosporidium apodemi sp. n. and Cryptosporidium ditrichi sp. n. (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae) in Apodemus spp. European Journal of Protistology 63, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danišová O, Valenčáková A, Stanko M, Luptaková L, Hatalová E and Canady A (2017) Rodents as a reservoir of infection caused by multiple zoonotic species/genotypes of C. parvum, C. hominis, C. suis, C. scrofarum, and the first evidence of C. muskrat genotypes I and II of rodents in Europe. Acta Tropica 172, 29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayer R (2010) Taxonomy and species delimitation in Cryptosporidium. Experimental Parasitology 124, 90–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y (2010) Cryptosporidium in wild placental mammals. Experimental Parasitology 124, 128–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Alderisio KA, Yang W, Blancero LA, Kuhne WG, Nadareski CA, Reid M and Xiao L (2007) Cryptosporidium genotypes in wildlife from a New York watershed. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 73, 6475–6483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foo C, Farrell J, Boxell A, Robertson I and Ryan UM (2007) Novel Cryptosporidium genotype in wild Australian mice (Mus domesticus). Applied and Environmental Microbiology 73, 7693–7696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S and Gascuel O (2003) A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Systematic Biology 52, 696–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajdušek O, Ditrich O and Šlapeta J (2004) Molecular identification of Cryptosporidium spp. in animal and human hosts from the Czech Republic. Veterinary Parasitology 122, 183–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall TA (1999) Bioedit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symposium Series 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hikosaka K and Nakai Y (2005) A novel genotype of Cryptosporidium muris from large Japanese field mice, Apodemus speciosus. Parasitology Research 97, 373–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeníková M, Němejc K, Sak B, Květoňová D and Kváč M (2011) New view on the age-specificity of pig Cryptosporidium by species-specific primers for distinguishing Cryptosporidium suis and Cryptosporidium pig genotype II. Veterinary Parasitology 176, 120–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Alderisio KA and Xiao L (2005) Distribution of Cryptosporidium genotypes in storm event water samples from three watersheds in New York. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 71, 4446–4454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jirků M, Valigurová A, Koudela B, Křižek J, Modrý D and Šlapeta J (2008) New species of Cryptosporidium tyzzer, 1907 (Apicomplexa) from amphibian host: morphology, biology and phylogeny. Folia Parasitologica (Praha) 55, 81–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kváč M, Ondráčková Z, Kvétoňová D, Sak B and Vitovec J (2007) Infectivity and pathogenicity of Cryptosporidium andersoni to a novel host, southern multimammate mouse (Mastomys coucha). Veterinary Parasitology 143, 229–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kváč M, Hofmannová L, Bertolino S, Wauters L, Tosi G and Modrý D (2008) Natural infection with two genotypes of Cryptosporidium in red squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris) in Italy. Folia Parasitologica 55, 95–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kváč M, McEvoy J, Loudová M, Stenger B, Sak B, Kvétoňová D, Ditrich O, Rašková V, Moriarty E, Rost M, Macholán M and Piálek J (2013) Coevolution of Cryptosporidium tyzzeri and the house mouse (Mus musculus). International Journal for Parasitology 43, 805–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kváč M, McEvoy J, Stenger B and Clark M (2014) Cryptosporidiosis in other vertebrates In Cacciò SM and Widmer G (eds), Cryptosporidium: Parasite and Disease. Wien: Springer, pp. 237–326. [Google Scholar]

- Kváč M, Vlnatá G, Ježková J, Horčičková M, Konečný R, Hlásková L, McEvoy J and Sak B (2018) Cryptosporidium occultus sp. n. (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae) in rats. European Journal of Protistology 63, 96–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laakkonen J, Soveri T and Henttonen H (1994) Prevalence of Cryptosporidium sp. in peak density Microtus agrestis, Microtus oeconomus and Clethrionomys glareolus populations. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 30, 110–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Xiao L, Alderisio K, Elwin K, Cebelinski E, Chalmers R, Santin M, Fayer R, Kváč M, Ryan U, Sak B, Stanko M, Guo Y, Wang L, Zhang L, Cai J, Roellig D and Feng Y (2014) Subtyping Cryptosporidium ubiquitum, a zoonotic pathogen emerging in humans. Emerging Infectious Diseases 20, 217–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv C, Zhang L, Wang R, Jian F, Zhang S, Ning C, Wang H, Feng C, Wang X, Ren X, Qi M and Xiao L (2009) Cryptosporidium spp. in wild, laboratory, and pet rodents in China: prevalence and molecular characterization. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 75, 7692–7699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma JB, Cai JZ, Ma JW, Feng YY and Xiao LH (2014) Occurrence and molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. in yaks (Bos grunniens) in China. Veterinary Parasitology 202, 113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miláček P and Vítovec J (1985) Differential staining of cryptosporidia by aniline-carbol-methyl violet and tartrazine in smears from feces and scrapings of intestinal mucosa. Folia Parasitologica 32, 50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modrý D, Hofmannová L, Antalová Z, Sak B and Kváč M (2012) Variability in susceptibility of voles (Arvicolinae) to experimental infection with Cryptosporidium muris and Cryptosporidium andersoni. Parasitology Research 111, 471–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Némejc K, Sak B, Květoňová D, Hanzal V, Jeníková M and Kváč M (2012) The first report on Cryptosporidium suis and Cryptosporidium pig genotype II in Eurasian wild boars (Sus scrofa) (Czech Republic). Veterinary Parasitology 184, 122–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng-Hublin JS, Singleton GR and Ryan U (2013) Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. from wild rats and mice from rural communities in the Philippines. Infection Genetics and Evolution 16, 5–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols GL, Chalmers RM and Hadfield SJ (2014) Molecular epidemiology of human cryptosporidiosis In Cacciò SM and Widmer G (eds), Cryptosporidium: Parasite and Disease. Wien: Springer, pp. 237–326. [Google Scholar]

- Perec-Matysiak A, Bunkowska-Gawlik K, Zalesny G and Hildebrand J (2015) Small rodents as reservoirs of Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia spp. in south-western Poland. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine 22, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perz JF and Le Blancq SM (2001) Cryptosporidium parvum infection involving novel genotypes in wildlife from lower New York State. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 67, 1154–1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi M, Wang H, Jing B, Wang D, Wang R and Zhang L (2015) Occurrence and molecular identification of Cryptosporidium spp. in dairy calves in Xinjiang, Northwestern China. Veterinary Parasitology 212, 404–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rašková V, Květoňová D, Sak B, McEvoy J, Edwinson A, Stenger B and Kváč M (2013) Human cryptosporidiosis caused by Cryptosporidium tyzzeri and C. parvum isolates presumably transmitted from wild mice. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 51, 360–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan U and Xiao L (2014). Taxonomy and molecular taxonomy In Cacciò SM and Widmer G (eds), Cryptosporidium: Parasite and Disease. Wien: Springer, pp. 3–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan UM, Monis P, Enemark HL, Sulaiman I, Samarasinghe B, Read C, Buddle R, Robertson I, Zhou L, Thompson RCA and Xiao L (2004) Cryptosporidium suis n. sp (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae) in pigs (Sus scrofa). Journal of Parasitology 90, 769–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santín M and Zarlenga DS (2009) A multiplex polymerase chain reaction assay to simultaneously distinguish Cryptosporidium species of veterinary and public health concern in cattle. Veterinary Parasitology 166, 32–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinski E, Hlebowicz E and Bednarska M (1993) Occurrence of Cryptosporidium parvum infection in wild small mammals in District of Mazury Lake (Poland). Acta Parasitologica 38, 59–61. [Google Scholar]

- Sinski E, Bednarska M and Bajer A (1998) The role of wild rodents in ecology of cryptosporidiosis in Poland. Folia Parasitologica 45, 173–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spano F, Putignani L, McLauchlin J, Casemore DP and Crisanti A (1997) PCR-RFLP analysis of the Cryptosporidium oocyst wall protein (COWP) gene discriminates between C. wrairi and C. parvum, and between C. parvum isolates of human and animal origin. FEMS Microbiology Letters 150, 209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenger BL, Clark ME, Kváč M, Khan E, Giddings CW, Dyer NW, Schultz JL and McEvoy JM (2015a) Highly divergent 18S rRNA gene paralogs in a Cryptosporidium genotype from eastern chipmunks (Tamias striatus). Infection Genetics and Evolution 32, 113–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenger BL, Clark ME, Kváč M, Khan E, Giddings CW, Prediger J and McEvoy JM (2015b) North American tree squirrels and ground squirrels with overlapping ranges host different Cryptosporidium species and genotypes. Infection Genetics and Evolution 36, 287–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenger BLS, Horčičková M, Clark ME, Kváč M, Čondlová S, Khan E, Widmer G, Xiao L, Giddings CW, Pennil C, Stanko M, Sak B and McEvoy JM (2018) Cryptosporidium infecting wild cricetid rodents from the subfamilies Arvicolinae and Neotominae. Parasitology 145, 326–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturdee AP, Chalmers RM and Bull SA (1999) Detection of Cryptosporidium oocysts in wild mammals of mainland Britain. Veterinary Parasitology 80, 273–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulaiman IM, Morgan UM, Thompson RC, Lal AA and Xiao L (2000) Phylogenetic relationships of Cryptosporidium parasites based on the 70-kilodalton heat shock protein (HSP70) gene. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 66, 2385–2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulaiman IM, Lal AA and Xiao LH (2002) Molecular phylogeny and evolutionary relationships of Cryptosporidium parasites at the actin locus. Journal of Parasitology 88, 388–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A and Kumar S (2013) MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30, 2725–2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres J, Gracenea M, Gomez MS, Arrizabalaga A and Gonzalez-Moreno O (2000) The occurrence of Cryptosporidium parvum and C. muris in wild rodents and insectivores in Spain. Veterinary Parasitology 92, 253–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vítovec J, Hamadejová K, Landová L, Kváč M, Květoňová D and Sak B (2006) Prevalence and pathogenicity of Cryptosporidium suis in pre- and post-weaned pigs. Journal of Veterinary Medicine B 53, 239–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L, Escalante L, Yang C, Sulaiman I, Escalante AA, Montali RJ, Fayer R and Lal AA (1999) Phylogenetic analysis of Cryptosporidium parasites based on the small-subunit rRNA gene locus. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 65, 1578–1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L, Fayer R, Ryan U and Upton SJ (2004) Cryptosporidium taxonomy: recent advances and implications for public health. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 17, 72–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Fayer R, Trout JM, Ryan UM, Schaefer 3rd FW and Xiao L (2004) Genotypes of Cryptosporidium species infecting fur-bearing mammals differ from those of species infecting humans. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 70, 7574–7577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler PE, Wade SE, Schaaf SL, Chang YF and Mohammed HO (2007a) Cryptosporidium spp. from small mammals in the New York City watershed. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 43, 586–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler PE, Wade SE, Schaaf SL, Stern DA, Nadareski CA and Mohammed HO (2007b) Prevalence of Cryptosporidium species in wildlife populations within a watershed landscape in southeastern New York State. Veterinary Parasitology, 147, 176–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.