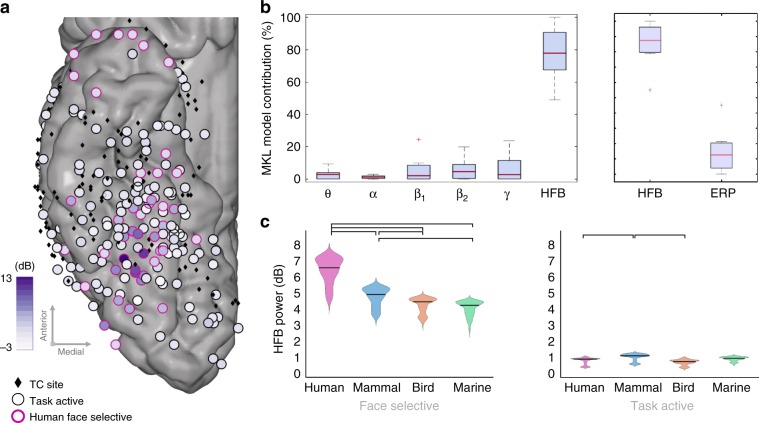

Fig. 1. Effect of species on face coding.

a Task-active and human face-selective sites across subjects in HFB. The coordinates of the electrodes from left hemisphere subjects were mirrored such that all sites could be displayed on a single hemisphere. Among the 357 included TC sites (represented by black diamonds), 190 were task active (represented by circles) as defined by permutation tests (i.e., presenting a significant response to at least one category). The difference between their response to human faces and non-face stimuli are displayed as a color-coded fill. In total, 48 task-active sites were identified as selective for human faces (represented with a pink contour). b HFB activity has the highest contribution in the discrimination between human faces and non-faces, within and across subjects. The results of the MKL model are plotted as box plots of the frequency band contributions to the model across the eight subjects, with the median represented by a red line. Similarly, HFB is favored over ERPs in an MKL model combining HFB power and ERPs. c HFB amplitude averaged within the [150 500]ms time window after onset for each of the four subcategories, in face-selective (left) and task-active sites (right). Coloring and initials represent the face subcategories: human (H/pink), mammal (M/blue), bird (B/orange), and marine (Ma/green). For face-selective sites, significant differences can be found (paired permutation tests, displayed by a black bracket) between the HFB responses to human faces and the mammal, bird, and marine faces, as well as between the mammal and the bird and marine faces. There is no significant difference between the responses to bird and marine faces. For task-active sites (i.e., active but not face selective), significant differences can be found between the bird faces and the human and mammal faces.