Abstract

Objectives

Eating disorders are common and serious conditions affecting up to 4% of the population. The mortality rate is high. Despite the seriousness and prevalence of eating disorders in children and adolescents, no Canadian practice guidelines exist to facilitate treatment decisions. This leaves clinicians without any guidance as to which treatment they should use. Our objective was to produce such a guideline.

Methods

Using systematic review, the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) system, and the assembly of a panel of diverse stakeholders from across the country, we developed high quality treatment guidelines that are focused on interventions for children and adolescents with eating disorders.

Results

Strong recommendations were supported specifically in favour of Family-Based Treatment, and more generally in terms of least intensive treatment environment. Weak recommendations in favour of Multi-Family Therapy, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, Adolescent Focused Psychotherapy, adjunctive Yoga and atypical antipsychotics were confirmed.

Conclusions

Several gaps for future work were identified including enhanced research efforts on new primary and adjunctive treatments in order to address severe eating disorders and complex co-morbidities.

Keywords: Guidelines, Adolescent, Anorexia nervosa, Bulimia nervosa, Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder

Plain English summary

The objective of this project was to develop Canadian Practice Guidelines for the treatment of children and adolescents with eating disorders. We reviewed the literature for relevant studies, rated the quality of the scientific information within these studies, and then reviewed this information with a panel of clinicians, researchers, parents and those with lived experience from across the country. The panel came up with a list of recommendations regarding specific treatments. These recommendations included strong recommendations for the provision of Family-Based Treatment, as well as care provided in a least intensive environment. Weak recommendations were determined for Multi-Family Therapy, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, Adolescent Focused Psychotherapy, adjunctive Yoga, and atypical antipsychotics. The panel also identified several areas for future research including the development of new treatments for severe and complex eating disorders.

Introduction

Eating disorders are common and serious conditions affecting up to 4% of the population [1]. The mortality rate, particularly for Anorexia Nervosa (AN) is high [2, 3], and has been shown to increase by 5.6% for each decade that an individual remains ill [4, 5]. It is well-documented that interventions targeted at earlier stages of illness are critically important, given the evidence showing that earlier treatment leads to better outcomes [6, 7]. Despite the seriousness and prevalence of eating disorders in children and adolescents, no Canadian practice guidelines exist to facilitate treatment decisions. This leaves clinicians without any guidance as to which treatment they should use. We systematically reviewed and synthesized the knowledge available on treatments for children and adolescents with eating disorders to develop our guidelines.

Review of existing guidelines

In the United States, practice parameters have been published by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry for youth with eating disorders [8]. These parameters reflect good clinical practice rather than making statements as to the strength of the evidence to support the recommendations. Clinical practice guidelines have also been developed by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence [9], however, grading of the evidence is also not presented in these guidelines. The Academy for Eating Disorders has also published guidelines on their website that focus on medical management, but do not focus on psychotherapeutic/psychopharmacological interventions, nor the strength of the evidence (http://aedweb.org/web/downloads/Guide-English.pdf). In summary, guidelines that are currently available tend to focus on medical stabilization, and neglect psychotherapeutic/psychopharmacological approaches to treating eating disorders. Furthermore, they do not rate the strength of evidence. No Canadian guidelines focused on eating disorders in the pediatric age group exist.

Objectives

Our aim was to synthesize the best available evidence on treatments for children and adolescents with eating disorders resulting in the production of a practice guideline. The research questions to drive this knowledge synthesis were discussed by our research team and guideline development panel, and are listed below.

Research questions

What are the best treatments available for children and adolescents diagnosed with eating disorders?

How effective is Family-Based Treatment for Anorexia Nervosa?

How effective is Family-Based Treatment for Bulimia Nervosa?

How effective is Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Bulimia Nervosa?

How effective is Dialectical Behaviour Therapy for Bulimia Nervosa?

How effective are Atypical Antipsychotics for Anorexia Nervosa?

How effective are Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors for Bulimia Nervosa?

How effective is day treatment for any type of eating disorder?

How effective is inpatient treatment for any type of eating disorder?

Methods

Overview

We used systematic review of the literature to arrive at a knowledge synthesis of the best treatments for children and adolescents with eating disorders. This was followed by a grading of the evidence using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) system [10–12]. These evidence profiles were then presented to a panel of stakeholders from across Canada, followed by a voting system and arrival at consensus on the recommendations. The Appraisal of Guidelines, Research, and Evaluation (AGREE II) tool was used to inform guideline development and reporting [13].

Synthesis methods

Eligibility criteria

Following the principles outlined in the Cochrane Reviewer’s Handbook [14] and the Users’ Guides to Medical Literature [15], our inclusion criteria were:

-

A)

Criteria pertaining to study validity: i) meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, open trials, case series, and case reports,

-

B)

Criteria pertaining to the subjects: i) involving children and adolescents (under age 18 years), ii) with eating disorders (Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa, Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified, Other Specified Feeding and Eating Disorder, Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder, Binge Eating Disorder),

-

C)

Criteria pertaining to the intervention: i) focusing on treatments including, but not limited to, Family-Based Treatment, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, Dialectical Behavioural Therapy, Atypical Antipsychotics, Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors, Day Treatment, and Inpatient Treatment,

-

D)

Criteria pertaining to the Outcome: i) weight (along with variants of weight such as BMI, treatment goal weight (TGW), etc.), ii) binge/purge frequency, iii) psychological symptoms such as drive for thinness, weight/shape preoccupation, and

-

E)

Articles written in any language.

Exclusion criteria included: i) studies involving primarily adults (18 years or above), ii) studies focusing on medical management, iii) studies focusing on medical outcomes such as bone density, heart rate, iv) studies examining medical treatments such as hormone therapy, calcium, nutrition therapy, v) studies examining other medications. These exclusion criteria were developed for several reasons. We wanted to focus on treatments that were psychopharmacological and psychological in nature, along with outcomes that were central to the core features of eating disorders. We were trying to keep things as simple as possible when thinking of outcomes, especially with the goal of trying to combine studies in a narrative summary or even in a meta-analysis if possible. We focused on a couple of core outcomes with these goals in mind, so therefore excluded papers focusing on other physical outcomes (although these outcomes may indeed be related to weight status).

Identifying potentially eligible studies

Databases

A literature search was completed using the following databases: Medline, PsycINFO, EMBASE, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and CINAHL. The references of relevant articles obtained were also reviewed. This was an iterative process, such that search terms were added based on developing ideas and articles obtained.

Literature search strategy

Initially, an environmental scan of existing guidelines for children and adolescents with eating disorders was completed by the core research team using search terms “guidelines” and “eating disorders” in children and adolescents. Our library scientist then designed and executed comprehensive searches in the databases listed above to obtain evidence to align with each of the guideline questions. The searches included a combination of appropriate keyword and subject heading for each concept. The sample search strategy included, but was not limited to, various combinations of the following terms as appropriate for the questions being addressed: Anorexia nervosa OR bulimia nervosa OR eating disorder not otherwise specified OR other specified feeding and eating disorder OR avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder; AND family-based treatment OR cognitive behavioural therapy OR dialectical behavioural therapy OR atypical antipsychotics OR selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors OR day treatment OR day hospital OR inpatient treatment. The search string was developed further and was modified for each database as appropriate. The search strategy was completed in August 2016. The screening and reviewing process then ensued. Some treatments emerged as important through our search strategy that were not initially identified by our research team and guideline panel as interventions to evaluate. We later included these treatments through panel discussions.

Forward citation chaining

In November 2018 we used a forward citation chaining process to search each included article to see if it had been cited by any additional articles since August 2016 up until November 2018. We then screened the newly found articles to decide whether to include them. The forward chaining process involved the use of Google Scholar to locate all articles citing our included articles from the primary search.

Other strategies

Grey literature was also reviewed, including conference proceedings from the International Conference on Eating Disorders dating back the last 10 years (2008–2018). Databases of ongoing research were searched including The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). We also hand searched the International Journal of Eating Disorders from the last 10 years for relevant articles (2008–2018).

Applying eligibility criteria and extracting data

Two team members independently evaluated the results generated by our searches and came to consensus on which studies met eligibility criteria. We used the software Endnote and DistillerSR to organize our studies. DistillerSR was used for article screening and data extraction. Duplicate records identifying the same study were removed. Titles and abstracts were used to exclude obviously irrelevant reports by two reviewers. Potentially relevant articles were reviewed in full text by two reviewers who had to agree on inclusion, with a third resolving disputes. Authors of publications were contacted if any ambiguity existed about inclusion or exclusion. Data abstraction included the number of subjects, sex and/or gender of subjects, age range, type of treatment, type of control group if any, methodology (blinding, allocation concealment, intent-to-treat analysis), types of outcomes, and results. Sex was defined as biological sex, categorized into male or female. Gender was defined as the individual’s self-identified gender role/identity, categorized as girl, boy, or transgendered.

Appraising studies

The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) system explicitly describes how to rate the quality of each study, as well as how to synthesize the evidence and grade the strength of a recommendation [10–12]. Using this system, we developed an evidence profile of each included study that detailed all of the relevant data about the quality and strength of evidence for that particular study. Each evidence profile was created using GRADEpro software. We then used the GRADE system to synthesize and classify the overall quality of evidence for each intervention based on the quality of all of the studies using that intervention combined, taking into account risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, publication bias, dose-response, and effect size. Although we looked at each outcome independently, when the rating of the evidence was the same, we collapsed the outcomes in the GRADEpro tables for the sake of efficiency.

Guideline-related frameworks

The Appraisal of Guidelines, Research, and Evaluation (AGREE II) tool is an international standard of practice guideline evaluation that was used to inform our guideline development and reporting, and was developed by a co-author (MB) [13]. The Guideline Implementability for Decision Excellence Model (GUIDE-M) is a recent model that identifies factors to create recommendations that are optimally implementable [16]. We used these models to guide our methodological processes in the development of our practice guideline.

The guideline team

The Guideline Team was comprised of a core research team and a larger guideline development panel (GDP). The core team presented the research questions to the GDP, reviewed evidence summaries, formulated practice recommendations, drafted the guideline, and limited biases that could impeach upon the guideline development process [17–19]. The chair of the GDP (MB) is an expert in guideline development having produced the AGREE framework [13]. She is a non-expert in the field of eating disorders, and as such, was an impartial chair. She led the consensus discussions of the GDP and she oversaw conflict-of-interest disclosures and management. A multidisciplinary GDP of 24 diverse stakeholders from across Canada was established including members from academic centres who are experts in the field of eating disorders, multi-disciplinary front-line clinicians/knowledge users from community settings, parent and patient representatives, hospital administrators, and policy-makers (all authors on this guideline).

Procedures

An initial teleconference was held on May 18, 2016 with the core research team and the GDP to confirm the research questions prior to starting the systematic reviews. The initial teleconference oriented GDP members to the guideline development process, the roles and responsibilities of the GDP, as well as reviewed all conflicts of interest. The research questions were refined, the clinical population and outcomes were discussed, and the target audience reviewed.

Once the reviews were completed and the evidence profiles were generated, an in-person meeting was held at a central location on December 20, 2018. The core research team presented their evidence profiles for discussion with the GDP. The in-person meeting focused on a facilitated discussion of the evidence profiles and draft recommendations generated by the core team. For each question, the panel reviewed the evidence, and discussed: i) whether the interpretation of the evidence put forward by the core team aligned with that of the GDP, ii) strengths and limitations of the evidence base, iii) considerations of the generalizability of the studies, precision of the estimates, and whether the evidence aligned with values and preferences of Canadian patients and clinicians. Alternative interpretations and suggestions for further research were discussed. Minority or dissenting opinions were noted. Issues regarding implementability of the recommendations were considered, and suggestions for dissemination of the guideline were elicited.

Following the in-person meeting, GDP members were provided with the draft guidelines for review and approval. Group consensus on recommendations and strength of recommendations was obtained using a modified Delphi method [20], with voting by all GDP members using an anonymous web-based survey platform, Lime Survey (www.limesurvey.com). For a recommendation to be approved, at least 70% of the GDP were required to identify their agreement with the recommendation [12]. Consensus was achieved in the first round of voting. The GDP agreed to review and update the guideline every 5 years.

External review

The purpose of the external review was to add validity to our guideline, but also initiate the dissemination process and elicit suggestions for dissemination and implementation. We invited review from four clinical and research experts in the area of pediatric eating disorders. Upon receiving external review, a summary of the review comments and suggestions was circulated to the GDP, along with a final version of the guideline for approval. The panel again discussed and voted on the changes suggested by the reviewers which included the addition of one further recommendation.

Results

Family therapy

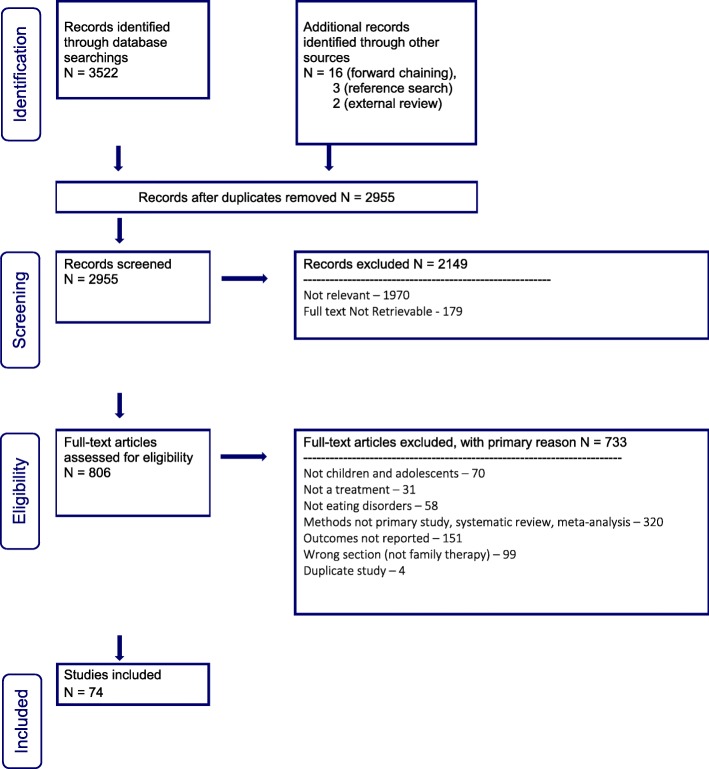

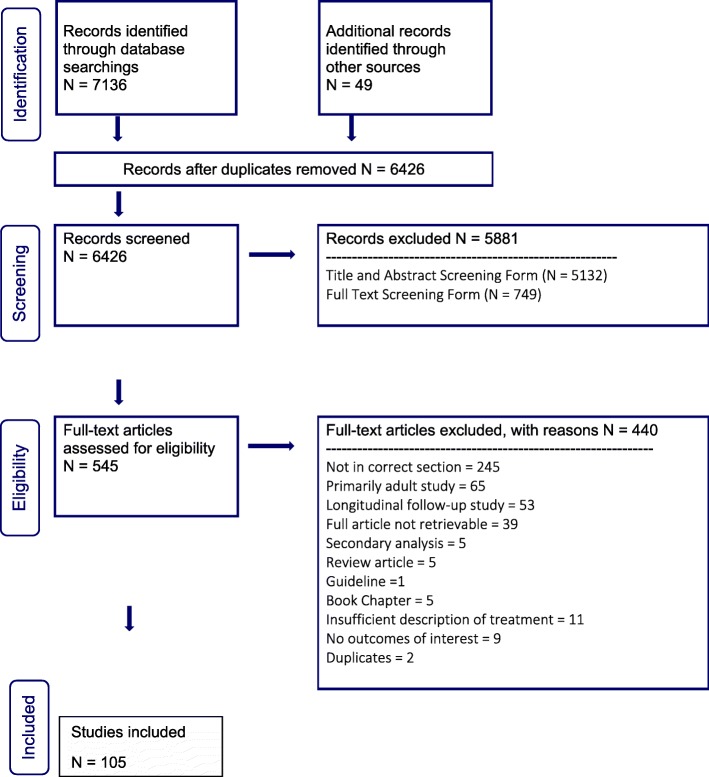

Three thousand, five hundred and twenty-two abstracts were identified for review within the family therapy section of our guideline (see PRISMA flow diagram, Fig. 1). Nineteen additional abstracts were identified through citation chaining (up to November 23, 2018) and review of reference lists. Two additional papers were identified through external review. After duplicates were removed, abstracts screened, and full text articles reviewed, 74 studies were included within the family therapy section of our guideline.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for family therapy

Family-based treatment

Anorexia nervosa

Of all treatments examined, Family-Based Treatment (FBT), in which parents are placed in charge of the refeeding process, had the most evidence to support its use in children and adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa (AN). One meta-analysis [21] and three high quality RCTs have demonstrated that greater weight gain and higher remission rates are achieved in FBT compared to individual treatment, especially when looking at 1 year follow up [6, 22, 23] (Table 1). One RCT compared a similar behavioural family systems therapy to Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) and found no significant differences [24], however the sample size was small (Table 1).

Table 1.

Family-based treatment – anorexia nervosa

| Certainty assessment | Impact | Certainty | Importance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |||

| FBT vs supportive/dynamic individual– outcomes - Remission (assessed with: attaining target weight, good outcome category) Weight gain | |||||||||

| 3 | randomised trials | not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | One meta-analysis indicated superiority of FBT at 6- and 12- month follow up. Three RCTs 43/90 (47.8%) with good outcome or in full remission with FBT, compared to 26/89 (29.2%) in Individual group. Total n = 179. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL |

| not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Weight gain greater in the FBT group compared to individual therapy group at end of treatment. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL | ||

| RCT (FBT vs CBT) Remission/Good Outcome (assessed with: Morgan Russell Scale) | |||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | 7/13 (53.8%) had a good outcome in FBT group vs. 7/12 (58.3%) in the CBT group. No significant difference. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL |

| Weight Gain (assessed with: kg and %IBW) | |||||||||

| 1 | Case control | serious b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | One case control retrospective chart review. 32 treated with FBT model compared to 14 in nonspecific therapy. Those in FBT made greater gains in weight. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

| Weight (assessed with: kg) | |||||||||

| 7 | Case series | very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | 7 large case series (total n = 223). Of these, 32 were children under age 13. Weight was significantly improved, pre to post. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

| Weight (assessed with: kg) | |||||||||

| 11 | Case reports | very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | 11 case reports detailing 29 patients who restored weight with FBT. Some described twins, comorbid conversion disorder, FBT within a group home setting, or FBT starting on a medical unit or use of FBT combined with medication. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

Bibliography:

RCTs - Russell 1987 [6], Lock 2010 [23], Robin 1999 [22] (compared to psychodynamic individual)

RCT – Ball 2004 [24] (compared to CBT)

Case Control -Gusella 2017 [25]

Case Series - Paulson-Karlsson 2009 [26], Lock 2006 [27], Le Grange 2005 [28], Loeb 2007 [29], Goldstein 2016 [30], Couturier 2010 [31], Herscovici 1996 [32]

Case Reports – Le Grange 1999 [33], Le Grange 2003 [34], Loeb 2009 [35], Sim 2004 [36], Krautter 2004 [37], Aspen 2014 [38], Matthews 2016 [39], Turkiewicz 2010 [40], O’Neil 2012 [41], Duvvuri 2012 [42], Goldstein 2013[43]

In terms of nonrandomized studies, a case-control study of 34 patients treated with FBT compared to 14 treated with “nonspecific therapy” indicated that those in FBT made greater gains in body weight and were less likely to be hospitalized [25]. Seven case series (223 patients) also showed improvement in weight following treatment with FBT [26–32]. Eleven additional case reports (number of total patients = 29) are described showing benefit of FBT in terms of weight gain [33, 35–38, 40–44]. Some of these focus on twins [35, 42, 44], comorbid conversion disorder [43], FBT in a group home setting [38], FBT started on a medical unit [39], and FBT combined with medication [42].

Parent-Focused Family Therapy; a type of FBT in which most of the session is spent with the parents alone, may be just as effective as traditional FBT where the family is seen together [45–47] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Parent focused FBT compared to standard FBT for children and adolescents with anorexia nervosa

| Certainty assessment | Impact | Certainty | Importance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |||

| Remission (assessed with: Weight greater than 95% and EDE score within 1 SD), Weight (kg), Psychological symptoms (EDI score) | |||||||||

| 3 | Randomized Trials | not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | one RCT (n = 107) adolescents aged 12–18. Remission higher in Separated FBT (43% vs. 22%) compared to Standard FBT at end of treatment. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL |

| not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none |

one RCT (n = 40), found no differences in weight outcome at end of treatment, except when subgroups analyzed. Those with high expressed emotion did better in separated family therapy in terms of weight gain. One pilot RCT (n = 18) found no differences in weight outcome at the end of treatment; both groups improved. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL | ||

| not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none |

Improvement in EDI score was greater in the standard FBT group compared to the separated group. One pilot RCT (n = 18) found both groups improved in EAT scores with no difference between groups. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL | ||

Bulimia nervosa

Three high quality RCTs for Bulimia Nervosa (BN) have been completed and compared FBT to varying groups [48–50]. When FBT was compared to CBT, remission rates were significantly higher in the FBT group (39% versus 20%) [50]. Remission rates were also significantly better in the FBT group compared to supportive psychotherapy (39% versus 18% )[48]. However, when family therapy (with some elements consistent with FBT) was compared to guided self-help CBT, there were no significant differences (10% versus 14%) [49]. The adolescents in this study were slightly older and had the option to involve a “close other” rather than a parent, which may have resulted in lower remission rates. A case series and case report also support the use of FBT for BN [34, 51] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Family-based treatment for bulimia nervosa

| Certainty assessment | Impact | Certainty | Importance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |||

| Remission (assessed with: Abstinence from binge or purge behaviour for 4 weeks) Psychological Symptoms (assessed with: EDE), Depression (assessed with: BDI), | |||||||||

| 3 | randomised trials | not serious | serious a,b,c | not serious | not serious | none | one RCT (n = 130) compared FBT to CBT for adolescents with BN. FBT group achieved significantly higher remission rates (39% vs. 20%) at end of study. One RCT (n-85) compared FBT to CBT guided self care and found no difference in BP remission (although Binge alone was decreased in the CBT group). One RCT randomized 80 patients to FBT or supportive psychotherapy. 39% in FBT vs. 18% in supportive therapy were in remission at end of treatment; a significant difference. |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE |

CRITICAL |

| not serious | serious a,b,c | not serious | not serious | none | one RCT (n = 130) did not find any differences in EDE score at end of treatment for FBT vs. CBT for adolescents with BN. The other RCT (n = 80) also showed all EDE scores were more improved in the FBT group compared to supportive group. |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE |

CRITICAL | ||

| not serious | serious a,b,c | not serious | not serious | none | One RCT (n = 130) showed a decrease in depression scores that was greater in the FBT group compared to the CBT group at the end of the study. Another RCT (n = 80) did not show any differences in depression scores between FBT and supportive group. |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE |

CRITICAL | ||

| Binge Purge Frequency (assessed with: Frequency Scores) | |||||||||

| 2 | Case Reports | very serious d,e | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Two case reports of 9 patients in total describe decreases in binge and purge behaviours with FBT pre compared to post. |

⨁⨁⨁◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

aone of three RCTs did not find a difference at end of treatment

bone RCT found a difference in psychological symptoms and the other did not

cone RCT showed a difference in depression scores and the other did not

dno randomization

e no control condition

Bibliography:

RCTs – Le Grange 2015 [50], Le Grange 2007 [48], Schmidt 2007 [49]

Family-based treatment with other populations

Family-Based Treatment has been used for children and adolescents with atypical AN [52]. This case series of 42 adolescents who were not underweight but had lost a significant amount of weight, indicated that there were significant improvements in eating disorder and depressive symptoms, but no improvement in self-esteem (Table 4).

Table 4.

Family-based treatment for other populations

| Certainty assessment | Impact | Certainty | Importance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |||

| Atypical AN - Depressive symptoms - Hughes 2017 (atypical AN) [52] | |||||||||

| 1 | Case series | very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Case series of 42 adolescents (age 12 to 18 years) with Atypical AN, that is adolescents who had lost a significant amount of weight, but were not currently underweight. There were significant decreases in eating disorder and depressive symptoms during FBT but no improvement in self esteem. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

| Case Reports - Spettigue 2018 [53], Murray 2012 [54] (ARFID) | |||||||||

| ARFID - Food Variety (assessed with: clinical impression), Weight | |||||||||

| 2 | Case Reports | very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Two case reports describe 7 cases in total (2 male, 5 female) in which ARFID was treated using a combination of FBT techniques, as well as some behavioural rewards and cognitive strategies. Food variety improved by clinical impression. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

| very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Weight improved in all cases. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL | ||

| Case Report - Strandjord 2015 (transgendered youth) [55] | |||||||||

| Transgendered Youth -BMI | |||||||||

| 1 | Case Report | very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | 16 yo female sex assigned at birth treated with FBT to weight restoration then disclosed gender dysphoria with a desire to transition to male gender. BMI 14.9 before treatment, and 19 with treatment. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

ano control condition

bno randomization

Two case reports describe the application of FBT for children with Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) [53, 54]. These case reports (n = 7 cases total) indicate that weight improved in all cases (Table 4).

Family-Based Treatment and other family therapies for children and adolescents with eating disorders across the gender spectrum, including those who are gender variant or nonconforming requires more study. However, there is one case report describing the application of FBT with a transgendered youth, along with complexities that arose [55] (Table 4).

Adaptations to family-based treatment for anorexia nervosa

Adaptations to FBT, such as shorter or longer treatment [56], removal of the family meal [57], guided self-help [58], parent to parent consult [59], adaptive FBT involving extra sessions and another family meal [60], short term intensive formats [61, 62] and delivery of FBT by telehealth [63, 64], appear promising, but require more study (Table 5).

Table 5.

FBT adaptations for children and adolescents with anorexia nervosa

| Certainty assessment | Impact | Certainty | Importance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |||

| Weight and Psychological Symptoms | |||||||||

| 1 |

randomised trials 10 vs 20 sessions |

not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | RCT comparing 10 sessions of FBT to 20 sessions of FBT (n = 86). No differences in weight seen at 1 year. Those with nonintact families and severe eating related obsessive-compulsive features fair better in FBT. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

IMPORTANT |

| not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | No differences in psychological symptoms (EDE) seen at 1 year. Those with nonintact families and severe eating related obsessive-compulsive features fair better in FBT. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

IMPORTANT | ||

| 1 |

randomised trials Adaptive vs. Standard FBT |

not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | 45 adolescents in RCT comparing Adaptive FBT (3 extra sessions) to Standard FBT. No differences in outcomes in terms of weight. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL |

| 1 |

Randomized trial FBT +/− family meal |

not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | One RCT examined FBT with and without the family meal intervention (n = 23). No differences were found in weight at the end of the study. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL |

| 1 |

randomised trials FBT alone vs. FBT plus parent consultation |

not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | RCT of 20 adolescents aged 12–16 all female. 10 received FBT plus parent to parent consultation and 10 received FBT alone. Small increase in rate of weight restoration was seen in FBT plus consultation group. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL |

| Weight | |||||||||

| 4 |

Case Series guided self help, short term intensive, telemedicine |

very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none |

Uncontrolled feasibility study looked at Parental guided self help FBT for AN (n = 19). Improvement in weight was seen at the end of the study. Uncontrolled Short-Term Intensive Family Based Treatment for AN (n = 19). 18/19 patients gained and maintained weight. 30 month outcome of 74 patients treated with this Short Term Intensive Modal indicated 61% remained in full remission. One case series (n = 10) showing benefit of FBT delivery via telemedicine. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

| Weight | |||||||||

| 1 | Case Report telemedicine | very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | One case report of FBT delivered by telehealth. Weight improved pre to post treatment. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

Adjuncts to family-based treatment for anorexia nervosa

Adjuncts to FBT, in which additional treatments have been added to FBT, such as cognitive remediation therapy versus art therapy [65], parental skills workshops [66] and Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (DBT) [67] for children and adolescents with AN show promise, but require further study (Table 6).

Table 6.

FBT adjuncts for children and adolescents with anorexia nervosa

| Certainty assessment | Impact | Certainty | Importance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |||

| Psychological symptoms (EDE) | |||||||||

| 1 |

randomised trials Art therapy vs. CRT |

not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | RCT examining FBT plus either Art Therapy or Cognitive Remediation Therapy. Global EDE score was slightly more improved in the Art Therapy Group (p < 0.03, n = 30). |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL |

| Weight Restoration (assessed with: Median BMI) | |||||||||

| 1 |

Case control FBT +/−skills workshop |

serious a | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | One case control study described 45 families who had FBT with 45 families who had FBT plus a parent education and skills workshop. Week 4 weight gain was higher in those with the workshop, but there were no significant differences at the end of the study. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

| Weight (assessed with: pounds and %expected body weight) | |||||||||

| 1 |

Case series DBT added |

very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | One case series (n = 11) of DBT added to FBT in a community-based clinic. 2/11 achieved full weight restoration at end of treatment |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

| very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | 6/11 had normal EDE scores at the end of the study. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL | ||

| Weight | |||||||||

| 2 |

Case reports Emotion coaching |

very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Two case reports of two patients with AN (one male) treated with adjunctive emotion coaching and the other with Attachment Based Family Therapy during a course of FBT. Both improved in weight to be fully weight restored. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

Two case reports describe the application of adjunctive emotion coaching and attachment based strategies to FBT for one male and one female patient with AN [68, 69] (Table 6).

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy has also been added as an adjunct to FBT for young patients with AN or BN. For AN, three case series [70–72] and two case reports [73, 74] indicate improved weight and psychological symptoms with added modules on perfectionism or exposure (Table 7). For BN, one case control study exists that compared one patient treated with FBT plus CBT to another patient treated with FBT alone, finding that both patients improved in terms of binge/purge symptoms and Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) scores [75] (Table 8).

Table 7.

FBT plus CBT for children and adolescents with anorexia nervosa

| Certainty assessment | Impact | Certainty | Importance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |||

| Weight (assessed with: percent ideal body weight) Psychological Symptoms of ED (assessed with: EDE and EDI) | |||||||||

| 3 | Case series adding CBT to FBT | very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Total n = 78. Three case series looked at a perfectionism module added to FBT, or an exposure component to FBT. Weight increased significantly. One case series looked at Acceptance-Based Separated Family Treatment (n = 47), and also noted weight improved to ideal weight in about 50% of cases from pre to post treatment (20 sessions over 24 weeks). |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

| very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | In one study 2/3 in full remission, 1/3 in partial remission. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL | ||

| very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Decreases in EDE scores and EDI scores reported. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL | ||

| Perfectionism (assessed with: Child and Adolescent Perfectionism Scale) | |||||||||

| 2 | Case reports | very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Two case reports (n = 9 total) report on decreased perfectionism scores with the addition of a CBT perfectionism module or the addition of acceptance-based strategies |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

IMPORTANT |

Table 8.

FBT plus CBT for children and adolescents with Bulimia Nervosa

| Certainty assessment | Impact | Certainty | Importance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |||

| Binge Purge Frequency (assessed with: frequency diary), Psychological symptoms (EDE) | |||||||||

| 1 | Case control | serious a | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | One 15 yo female treated with FBT alone, compared to one 15 yo female treated with FBT and CBT (1 h sessions were split into 30 min of FBT and 30 min of CBT). Both improved significantly - BP episodes decreased from 10 to 12 episodes per week to 0. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

IMPORTANT |

| serious a | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | EDE scores were collected at end of this CBT plus FBT compared to FBT alone study (n = 2). EDE scores were similar in these two patients and demonstrated normal scores (in remission). |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

IMPORTANT | ||

Multi-family therapy

One large high quality RCT (n = 169) found that Multi-Family Therapy (MFT) conferred additional benefits compared to single family therapy (FT) in terms of remission rates for adolescents with AN (75% in MFT versus 60% in FT), although no differences were found on the EDE [76]. There is one case control study examining MFT versus treatment as usual (TAU) in 50 female adolescents with AN [77]. Those in the MFT group had a higher percent body weight (99.6%) versus the TAU group (95.4%) at the end of the study. Two case series have also demonstrated a benefit of MFT for adolescents with AN [78, 79], and one case series with a mixed sample of adolescents with AN or BN showed benefit in psychological symptoms [80]. There is also one small case series examining MFT for adolescents with BN that found improvements in eating disorder symptoms [81] (Table 9).

Table 9.

Multi family therapy for eating disorders

| Certainty assessment | Impact | Certainty | Importance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DE | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |||

| Good Outcome at End of Treatment (assessed with: Morgan Russell Scale), Psychological Symptoms (EDE) | |||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none |

RCT (n = 169) of adolescents with AN aged 11–18 comparing MFT to FBT (91% female). 65/86 (75.6%) good outcome at end of treatment in MFT versus 48/83 (57.8%) in the FBT group - significant difference. No differences between groups seen on the EDE. Both groups improved over time on the EDE. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL |

| not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | No differences between groups seen on the EDE. Both groups improved over time on the EDE. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL | ||

| Weight (assessed with: Percent ideal body weight) | |||||||||

| 1 | Case control | serious a | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Retrospective case control study looking at MFT versus TAU for AN. 50 female adolescents aged 11–18 were included (25 in MFT group and 25 in TAU group). Those in MFT restored weight to a higher percentage (99.6% vs. 95.4%). |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

| Weight (assessed with: kg and BMI) Psychological Symptoms (assessed with: EDE, EDI) | |||||||||

| 4 | Case Series | very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Four studies without a control condition. Total n = 142 adolescents (5 males, 137 females), Diagnoses were mixed including AN, EDNOS and BN. Significant improvements in weight were reported. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

| very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none |

Improvements in psychological symptoms were seen pre to post MFT. In a case series of 10 adolescents aged 13 to 18 years, EDE scores decreased from 4.31 to 3.41 (cohen’s d 0.82). |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL | ||

Other forms of family therapy

Systemic Family therapy has been used in one RCT [82] and three case reports [83–85] for AN. The high quality RCT compared Systemic Family Therapy to FBT and found no significant differences in terms of remission rates, however, rate of weight gain was greater in the FBT group and the use of hospitalization was also significantly lower in the FBT group (Table 10). Structural Family Therapy has been studied within two case series [86, 87] and two case reports [88, 89]. Remission rates in the case series were 75% (38/51) by clinical impression (Table 11). Both of these types of family therapy (Systemic and Structural) might be helpful for children and adolescents with AN, but the evidence generally does not indicate superiority to FBT, especially when costs are taken into consideration.

Table 10.

Systemic family therapy for anorexia nervosa

| Certainty assessment | Impact | Certainty | Importance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |||

| Systemic Family Therapy vs. FBT- Remission (assessed with: greater than 95% IBW) | |||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | One RCT n = 164 (82 in each group, 141 were female). Remission rates were 27/82 in the FBT group and 21/82 in the Systemic Group - not significantly different. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL |

| not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Rate of weight gain were significantly faster in the FBT group compared to the Systemic Group. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL | ||

| not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | No differences were seen in EDE score at end of treatment between FBT and Systemic Therapy |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL | ||

| Weight (assessed with: kg) | |||||||||

| 3 | Case Reports | very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Three case reports describe the use of systemic family therapy to good effect in terms of weight restoration. One case was a 14 yo male in which only the parents came to some of the sessions, another was a 15 yo female with comorbid osteosarcoma, and another is a 15 yo male. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

IMPORTANT |

Table 11.

Structural family therapy for children and adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa

| Certainty assessment | Impact | Certainty | Importance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |||

| Recovery (assessed with: clinical impression), Weight Gain | |||||||||

| 2 | Case series | very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Two large case series of 51 female adolescents total used structural family therapy. 38/51 (75%) were deemed recovered by clinical impression. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

| very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | One of these case series reported between 5 and 31 kg of weight gain with the treatment (n = 25). |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL | ||

| Weight Gain (assessed with: kg) | |||||||||

| 2 | Case reports | very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Two case reports (n = 2 both female) report weight restoration - one of these cases had co-morbid asthma. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

When looking at other nonspecific, family therapies in which family dynamics were examined, there is one high quality RCT which compared family therapy plus TAU to TAU alone [90] and three case reports [91–93] indicating a benefit of family therapy (Table 12). Family therapy has also been compared to family group psychoeducation with no significant differences in outcomes [94]. Both groups were recruited through an inpatient program. Both groups gained weight and were receiving other forms of treatment including medical monitoring and nutritional advice, in addition to the interventions of interest (Table 13).

Table 12.

Family therapy (dynamic) for children and adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa

| Certainty assessment | Impact | Certainty | Importance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |||

| RCT - Good Outcome (assessed with: Morgan Russell) | |||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | one RCT involving 60 adolescents randomized to TAU or TAU plus Family Therapy looking at family dynamics. 12/30 had a good outcome in the FT group compared to 5/30 in the TAU group (p < 0.05). |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL |

| Weight (assessed with: kg) | |||||||||

| 3 | Case Reports | very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | three case reports looking at 4 female patients (one set of twins) treated with family therapy (one solution focused). Weight improved in all cases. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

IMPORTANT |

Table 13.

Family therapy compared to family group psychoeducation for adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa

| Certainty assessment | Impact | Certainty | Importance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |||

| Weight Restoration (assessed with: kg) | |||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | No differences in weight restoration were seen at the end of the study between treatments. Both groups gained weight. (n = 25). |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

IMPORTANT |

Bibliography:

Geist 2000 [94]

Emotion focused family therapy (EFFT) was compared in a randomized trial to CBT for 13 adolescents with BN [95] (Table 14). No differences were found in terms of binge/purge symptoms or psychological symptoms at the end of the study, however, the study was likely underpowered to detect differences.

Table 14.

Emotion focused family therapy compared to cognitive behavioural therapy for children and adolescents with Bulimia Nervosa

| Certainty assessment | Impact | Certainty | Importance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |||

| Binge Purge Frequency (assessed with: frequency), Psychological Symptoms (assessed with: EDI) | |||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | not serious | not serious | not serious | seriousa | none | n = 13 adolescents with BN randomly assigned to EFFT or CBT. No differences in terms of binge purge frequency at end of study. |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE |

CRITICAL |

| not serious | not serious | not serious | seriousa | none | No differences in terms of psychological symptoms at end of study. Very small sample size. |

⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE |

CRITICAL | ||

Individual and group outpatient psychotherapies

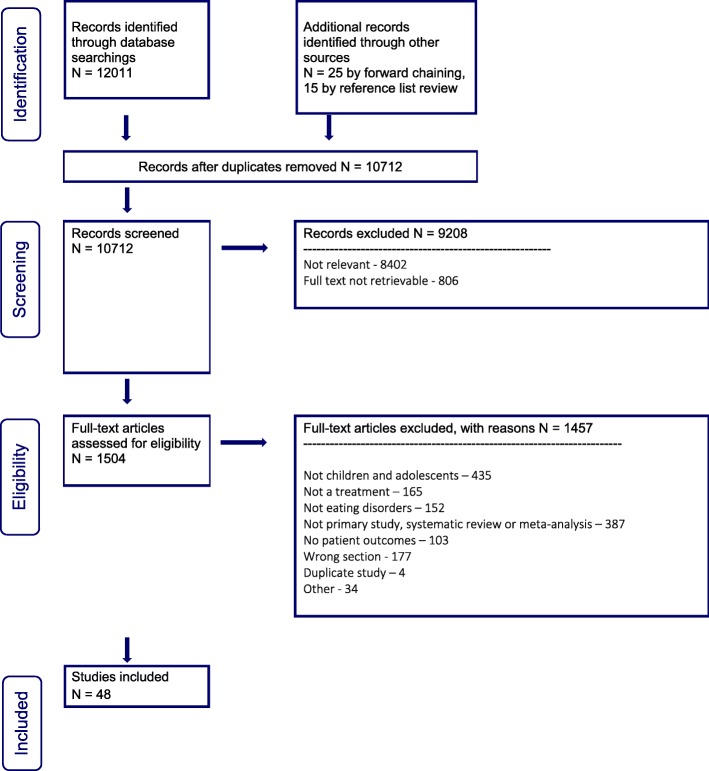

Twelve thousand and eleven abstracts were identified in our database searches for the individual and group psychotherapy section of our guideline (see PRISMA flow diagram, Fig. 2). Twenty-five were added with forward chaining up to November 21, 2018, and 15 more through reference list review. Nine thousand, two hundred and eight abstracts were excluded during the abstract screening phase, and a further 1457 were excluded based on full article review, leaving a total of 48 articles included.

Fig. 2.

PRISMA flow diagram for individual and group psychotherapy

Cognitive Behavioural therapy

Anorexia nervosa

A small RCT (n = 22) did not show any difference between CBT and Behavioural Family Therapy (similar to FBT) in terms of weight, or psychological symptoms on the EDE for children and adolescents with AN, however, both groups improved [24] (Table 15). One large case series [96] indicated that CBT resulted in weight gain and improvement in eating disorder psychological symptoms for children and adolescent with AN (n = 49). Eight additional case reports [97–104] support these results as well. Improvements have also been shown when CBT is delivered in a group setting for AN in a case control design involving 22 patients [105], and in a case series of 29 adolescents [106] (Table 16).

Table 15.

Cognitive behavioural therapy for Anorexia Nervosa

| Certainty assessment | Impact | Certainty | Importance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |||

| Weight (assessed with: BMI), Psychological symptoms (EDE) | |||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | RCT with 11 adolescents and young adults in CBT group compared to 11 in the Behavioural Family Therapy group (age range 13–23). There were no significant differences in terms of weight. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL |

| not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | No differences seen in the eating psychopathology on the EDE between treatment groups. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL | ||

| Weight (assessed with: kg), psychological symptoms with EDE | |||||||||

| 1 | Case Series | very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | strong association | This was a large case series of 49 adolescents age 13 to 17 years, all female. 40 sessions weekly for 45 min. Weight was significantly increased by an average of 8.6 kg comparing pre to post weight. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

| very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | strong association | EDE scores were substantially decreased by a score of 2.03 (range 0–6) indicating psychological symptoms were much improved from pre to post treatment. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL | ||

| Weight (assessed with: kg), psychological symptoms | |||||||||

| 8 | Case Reports | very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | 8 case reports describing 8 adolescents (7 females, 1 male) with AN treated with CBT. One case had comorbid OCD. Weight improved with treatment. Age range 11.5 to 17 years. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

| very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Improved EDE scores and EDI scores as well as improved eating behaviours in terms of a reduction in restricted eating. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL | ||

Explanations

ano randomization

bno control condition

Bibliography:

RCT - Ball 2004 [24]

Case Series - Dalle Grave 2013 [96]

Case Reports - Cowdrey 2016 [97], Cooper 1984 [98], Martin-Murcia 2011 [99], Heffner 2002 [100], Scrignar 1971 [101], Fundudis 1986 [102], Ollendick 1979 [103], Wildes 2011 [104]

Table 16.

Group cognitive behavioural therapy for children and adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa

| Certainty assessment | Impact | Certainty | Importance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |||

| Weight (assessed with: kg) Psychological Symptoms of ED (assessed with: EDE) | |||||||||

| 1 | Case Control | serious a | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | This controlled study involved 11 adolescents in the CBT group condition compared to 11 adolescents in the treatment as usual condition. CBT group involved 24 sessions (90 min each) over a six-month period. There were no significant differences in terms of weight at the end of treatment. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

| serious a | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Significant difference on the EDE subscale of Restraint (0.56 vs. 0.70 - clinical significance questionable). |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL | ||

| Weight (assessed with: BMI) Psychological Symptoms of ED (assessed with: EDE) | |||||||||

| 1 | Case Series | very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Case series of 29 adolescent females (22 AN-R, 7 AN-BP). No control group. 40 sessions of group CBT over 40 weeks. Weight (BMI) improved pre to post treatment. EDE restraint and EDE weight concern improved Pre to Post treatment. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

Bulimia nervosa

For BN, three high quality RCTs were found examining CBT (Table 17). One RCT compared CBT to psychodynamic therapy in primarily adolescents, but also some young adults. This trial did not find any difference in terms of remission from BN. There were small differences in terms of a greater reduction in binge-purge frequency in the CBT group [107]. There were also two high quality RCTs identified comparing CBT to family-based approaches for BN [49, 50]. There are conflicting results between these two studies, with the study by Le Grange and colleagues [50] indicating significantly greater remission rates in the FBT group compared to the CBT group, whereas the study by Schmidt and colleagues [49] showed no significant difference between the groups with only a small proportion remitted in each group. Two large case series indicate significant decreases in binge-purge frequency pre to post treatment [108, 109]. Several case reports indicating improvement in binge-purge symptoms exist [110–114].

Table 17.

Cognitive behavioural therapy for Bulimia Nervosa

| Certainty assessment | Impact | Certainty | Importance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |||

| CBT vs FBT - Remission (assessed with: abstinence from BP for 4 weeks) | |||||||||

| 2 | randomised trials | not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | RCT n = 130 aged 12–18 years. 18 sessions over 6 months. 20% remitted in CBT group versus 39% remitted in FBT group (p < 0.04, NNT = 5). RCT n = 85 (guided self care CBT) remitted 6/44 in CBT group versus 4/41 in family group. no significant difference. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL |

| CBT vs. Psychodynamic - Remission Rates (assessed with: Diagnostic Criteria) | |||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none |

one RCT 81 females mean age 18.7 years (range 14–20). 33.3% remitted in the CBT group and 31.0% in the psychodynamic group. No significant differences. Mean of 37 sessions. Both groups improved, there were small between groups effect sizes for binge eating (d = 0.23) and purging (d = 0.26) in favour of CBT and for eating concern (d = 0.35) in favour of PDT. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL |

| Binge Purge Behaviour (assessed with: EDE) | |||||||||

| 2 | Case Series | very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Two large case series (n = 68 including 2 males, 66 females, and n = 34 all female). Total age range 12–19. Number of sessions 16–20. Frequency of binge and purge episodes decreased significantly pre to post treatment. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

| very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Case series of 68 adolescents - EDE significantly improved global EDE score from 3.6 to 1.8 from pre to post treatment. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL | ||

| Binge Purge Frequency (assessed with: Frequency), Psychological Symptoms (EDE or EAT) | |||||||||

| 5 | Case Reports | very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Case reports involving 9 patients in total. Frequency of binge and purge behaviours described as decreased. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

| very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | 7 cases -EDE or EAT significantly improved. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL | ||

Explanations

ano randomization

bno control condition

Bibliography:

RCT – Le Grange 2015 [50], Schmidt 2007 [49] (CBT vs. FBT) Stefini 2017 [107] (CBT vs. psychodynamic)

Case Series - Dalle Grave 2015 [108], Lock 2005 [109]

Case Reports – Schapman-Williams 2006 [110], Cooper 2007 [111], Anbar 2005 [112], Schapman-Williams 2007 [113], Sysko 2011 [114]

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder

There were 13 case reports identified in which CBT was used to treat ARFID [115–127]. One of these described the delivery of CBT by telemedicine [127]. One case described the combined treatment of CBT with fluoxetine for a significant choking phobia [120]. Although these reports are preliminary, improvements in food avoidance were noted in all cases (Table 18).

Table 18.

Cognitive behavioural therapy for ARFID

| Certainty assessment | Impact | Certainty | Importance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |||

| Avoidance of Food (assessed with: clinical impression) | |||||||||

| 12 | Case Reports | very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | 28 cases are described in which various cognitive behavioural strategies including systematic desensitization (17), hypnosis (6) and EMDR (4) were used. Patients were aged 3 to 16 years (12 male, 16 female). Improvement in food avoidance behaviour was reported in all cases. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

IMPORTANT |

| Telemedicine - Increased food variety (assessed with: bites of nonpreferred food) | |||||||||

| 1 | Case Report | very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Case report with CBT delivered by teleconsultation to parents of 8 year old boy with ARFID. Increased frequency of bites of nonpreferred food was noted. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

IMPORTANT |

Explanations

ano randomization

bno control condition

Bibliography:

Case Reports - Murphy 2016 [125], Fischer 2015 [124], Nock 2002 [119], Okada 2007 [122], Ciyiltepe 2006 [121], de Roos 2008 [123], Culbert 1996 [117], Siegel 1982 [115], Reid 2016 [126], Chatoor 1988 [116], Chorpita 1997 [118], Bloomfield 2018 [127], Bailly 2003 [120]

Adolescent focused psychotherapy

Anorexia nervosa

Adolescent Focused Psychotherapy (AFP: based on psychodynamic principles) [22, 23, 128] and other psychodynamic treatments [129] have some evidence to support their use (Table 19). Remission rates were not significantly different between AFP and FBT in two RCTs involving a total sample of 158 adolescents with AN [22, 23]. Rates of 20% (12/60) remitted in AFP compared to 34% (21/60) in FBT were found in a study by Lock and colleagues [23], whereas 41% in the AFP group met the weight goal of the 50th percentile in a study by Robin and colleagues [22] compared to 53% in the FBT group. Differences between AFP and FBT became more apparent at 1 year follow-up with FBT demonstrating an advantage [23]. Group analytic psychotherapy also has some evidence to support its use for AN [130] (Table 20). Psychodynamic Therapy (group or individual) for AN may be beneficial, however other treatments have some advantages over psychodynamic therapy in terms of cost and more rapid improvement in symptoms.

Table 19.

Adolescent focused psychotherapy/psychodynamic for Anorexia Nervosa

| Certainty assessment | Impact | Certainty | Importance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |||

| Remission (assessed with: normal weight and EDE score) | |||||||||

| 2 | randomised trials | not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | RCT of Adolescent Focused Psychotherapy versus FBT (n = 121, 11male, 110 female, age 12–18). 12/60 (20%) remitted at end of treatment in AFT group versus 21/61 (34.4%) in FBT group. No significant differences in terms of remission. No differences in remission in another RCT (n = 37). 52.6% in FBT reached 50th percentile weight vs. 41.2 in individual (p < 0.05). |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL |

| not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Those in FBT had greater change on EDE scores at end of treatment. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL | ||

| Weight | |||||||||

| 2 | Case Reports | very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Two case reports describing three cases total (age 12–16 years, all female) in which psychodynamic therapy over 1–2 years of therapy resulted in weight restoration. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

Table 20.

Group analytic therapy for children and adolescents with AN and BN

| Certainty assessment | Impact | Certainty | Importance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |||

| Psychological Symptoms (assessed with: EDI, SEED-short evaluation eating disorders) | |||||||||

| 1 | Case Reports | very serious a | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | 8 female adolescents aged 15–17 (3 with AN, 5 with BN). SEED AN and EDI maturity fears significantly decreased from pre to post. Setting was outpatient - 2 years 1.5 h per week |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

IMPORTANT |

Dialectical Behavioural therapy

Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (DBT) for eating disorders has been applied for youth with AN, BN, Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (EDNOS) and Binge Eating Disorder (BED) with promising results [131–133]. Two case series report decreases in binge-purge symptoms, and improvements in psychological eating disorder symptoms [131, 133], along with reductions in frequency of self-harm in multi-diagnostic youth [131] (Table 21).

Table 21.

Dialectical behavioural therapy for eating disorders

| Certainty assessment | Impact | Certainty | Importance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |||

| Binge Frequency (assessed with: number per month) Purge Frequency | |||||||||

| 2 | Case Series | very serious a | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Two case series and one case report for a total of 22 patients (10 EDNOS, 6 AN, 6 BN) reported a significant decrease in binge frequency. Reduction in vomiting pre and post treatment. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

IMPORTANT |

| very serious a | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | There were decreases in psychological symptoms. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

IMPORTANT | ||

| very serious a | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | A decrease in self harm also noted. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

IMPORTANT | ||

| Binge Frequency, EDE scores | |||||||||

| 1 | Case Report | very serious a | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | N = 1 female with BED – decreased frequency of binge episodes |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

IMPORTANT |

| very serious a | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | improvement in EDE scores. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

IMPORTANT | ||

Adjunctive treatments

Cognitive Remediation Therapy (CRT) has been mentioned in the family therapy section of this guideline as an adjunct to FBT [65], however, it has also been studied as an adjunct to other therapies in a case series [134] and a case report [135] for AN (Table 22). It has been used in multiple settings and will be touched upon again within the level of care section of this guideline.

Table 22.

Cognitive remediation therapy for children and adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa

| Certainty assessment | Impact | Certainty | Importance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |||

| ART vs. CRT - Weight (assessed with: BMI), ED symptoms, depression, anxiety | |||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | RCT comparing Art Therapy and CRT (both receiving FBT) n = 30 (3 male, 27 female). BMI not significantly different. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL |

| not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Art Therapy significantly better than CRT in terms of global EDE score at the end of 15 sessions. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL | ||

| not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | No difference between CRT and Art Therapy with respect to depression scores. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL | ||

| not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | No difference between CRT and Art Therapy with respect to Anxiety scores |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL | ||

| Weight (assessed with: BMI), Depression (BDI), Anxiety (STAI) | |||||||||

| 1 | Case Series | very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | One open trial of 20 patients (10 inpatients, 10 outpatients) describes weight improvement with 10 sessions of CRT. Open trial was pre post CRT. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

| very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Depression scores decreased significantly following CRT (pre compared to post) |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL | ||

| very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | No differences pre and post were seen in terms of Anxiety. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL | ||

| Weight | |||||||||

| 1 | Case Report | very serious a,b | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Case report – 12 year old female with AN - pre post and 7 month follow up after 10 sessions CRT. Weight improved at the follow up assessment to a healthy weight range. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

IMPORTANT |

One high quality study suggests some benefits of adjunctive yoga in terms of psychological symptoms of eating disorders, as well as depression and anxiety [136]. In this study, 50 girls and 4 boys were randomly assigned to an 8-week trial of yoga plus standard care versus standard care alone. The majority of the participants had AN (29/54), and others were diagnosed with BN (9/54) and EDNOS (15/54). Eating disorder symptoms measured by the EDE decreased more significantly in the yoga group. Both groups demonstrated maintenance of body mass index (BMI), along with decreases in anxiety and depression scores (Table 23).

Table 23.

Yoga for eating disorders

| Certainty assessment | Impact | Certainty | Importance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |||

| Psychological Symptoms (assessed with: EDE), weight, anxiety, depression | |||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | In this RCT 50 girls and 4 boys were randomized to yoga plus standard treatment, or standard treatment alone.. There were no differences in weight between the yoga group and the no yoga group at the end of the study. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL |

| not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | The yoga group demonstrated greater decreases in EDE score at 12 weeks. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL | ||

| not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Anxiety scores improved over time in the yoga group and were significantly improved compared to the no yoga group. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL | ||

| not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Depression scores were significantly improved in the yoga group compared to the control group. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL | ||

Bibliography:

RCT - Carei 2010 [136]

Medications

Atypical antipsychotics

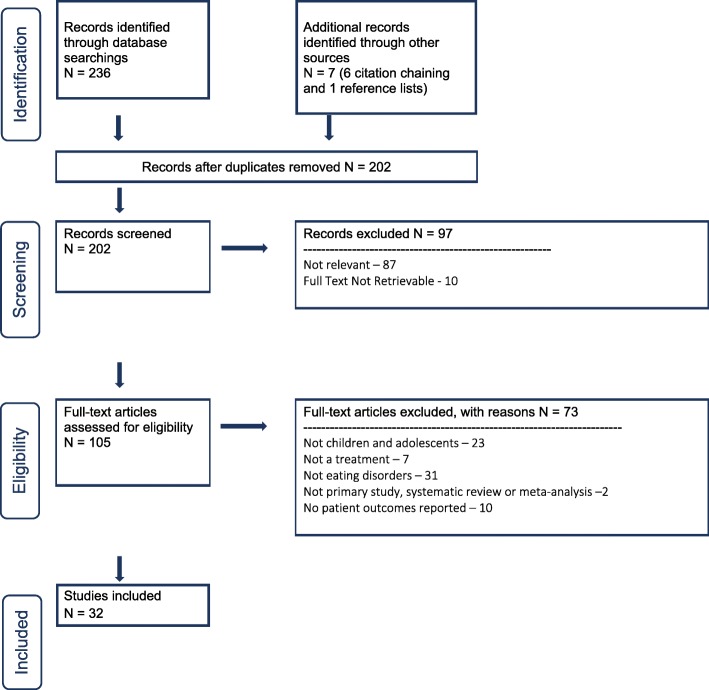

Two hundred and thirty-six abstracts were identified through database searching for the atypical antipsychotic section of our guideline (see PRISMA flow diagram Fig. 3). Seven additional articles were found through citation chaining and reference list review. After excluding 97 abstracts and then excluding 73 full text articles we arrived at 32 included studies for the atypical antipsychotic section. We then divided up the antipsychotics into their respective categories – Olanzapine, Risperidone, Quetiapine, and Aripiprazole.

Fig. 3.

PRISMA flow diagram for antipsychotics

Olanzapine

Anorexia nervosa

Olanzapine has been the most commonly studied psychotropic medication for children and adolescents with AN (Table 24). At present, only one double blind placebo-controlled trial in this population has been published. Kafantaris and colleagues [137] examined olanzapine in 20 underweight adolescents being treated in inpatient (n = 9), day treatment (n = 6) and outpatient (n = 5) settings (age range 12.3 to 21.8 years). In a 10-week pilot study, they found no differences in beneficial effect between the olanzapine and placebo groups in the 15 subjects who completed the trial; however, the treated group showed a trend towards increasing fasting glucose and insulin levels by the end of the study. The mean dose of olanzapine was 8.5 mg daily. Of note, only 21% of eligible patients were recruited into the study and there was a high attrition rate. Although other research teams have also attempted RCTs using olanzapine in this population, trials have been hampered by a myriad of confounding and recruitment issues [155].

Table 24.

Olanzapine for children and adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa

| Certainty assessment | Impact | Certainty | Importance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |||

| Weight (assessed with: BMI), Psychological Symptoms, Side Effects | |||||||||

| 1 | randomised trials | not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | RCT with 10 subjects in olanzapine group and 10 in placebo group. No differences were found between groups in rate of weight restoration or final weight. Difference in BMI was 0.4 kg/m2 and was not significant. Mean dose was 8.5 mg/day. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL |

| not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | No differences in eating disorder symptoms or psychological functioning. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL | ||

| not serious | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | A trend of increasing fasting glucose and insulin levels were found in the olanzapine group. |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ HIGH |

CRITICAL | ||

| Weight gain, activity levels, side effects | |||||||||

| 3 | Case Control | serious a | not serious | not serious a | not serious | none | There are three non randomized case control studies. One of the studies found the rate of weight gain was greater in the olanzapine group, while another study found no differences between cases and controls in terms of weight gain. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

| serious a | not serious | not serious a | not serious | none | Reduced activity levels were observed in one study. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL | ||

| serious a | not serious | not serious a | not serious | none | Sedation and dyslipidemia was found in 56% of patients in one study. One study found that 32% of patients discontinued the treatment due to a side effect. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL | ||

| Weight, hyperactivity, side effects | |||||||||

| 2 | Case Series | very serious a | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | 60 patients total involved in these two case series. Improvements in weight noted. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

| very serious a | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Improvements in hyperactivity are noted. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL | ||

| very serious a | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | No long term adverse effects were seen 3 months after discontinuing medication. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL | ||

| Weight, side effects | |||||||||

| 13 | Case Reports | very serious a | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | Thirteen studies report on 30 cases. All studies report improvement in weight. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL |

| very serious a | not serious | not serious | not serious | none | One case study reports on QTc prolongation (a problem on the ECG), another reports a case with neuroleptic malignant syndrome. |

⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW |

CRITICAL | ||

Explanations

aobservational study, non randomized

Bibliography:

RCT - Kafantaris 2011 [137]

Case Control - Spettigue 2018 [138], Norris 2011 [139], Hillebrand 2005 [140]

Case Series -Swenne 2011 [141], Leggero 2010 [142]

Case Reports - Pisano 2014 [143], Duvvuri 2012 [42], Dennis 2006 [144], Boachie 2003 [145], Mehler 2001 [146], La Via 2000 [147], Dadic-Hero 2009 [148], Hein 2010 [149], Tateno 2008 [150], Ercan 2003 [151], Dodig-Curkovic 2010 [152], Ayyildiz 2016 [153], Ritchie 2009 [154]

Three case control studies have examined the use of olanzapine in children and adolescents with AN [138–140]. The most recent of these studies enrolled 38 patients with AN; 22 of whom took olanzapine and 10 who declined medication and were retained as a comparison group [138]. The mean dose of medication was 5.28 mg daily over a 12-week trial period. Those in the medication group demonstrated a significantly higher rate of weight gain in the first 4 weeks, although approximately one third of participants discontinued olanzapine early due to side effects [138]. Norris and colleagues [139] completed a retrospective chart review of 22 inpatients treated with olanzapine compared to an untreated age-matched group. The rate of weight gain was not significantly different, however, the treated group had more psychiatric co-morbidities than those not taking olanzapine and experienced side effects of sedation and dyslipidemia [139]. Hillebrand and colleagues [140] also reported on olanzapine use in seven patients (mean age 16.0 years) with AN. Most were taking 5 mg of olanzapine, with one patient receiving 15 mg once daily. The authors found reductions in activity levels in the adolescents taking olanzapine in comparison to 11 adolescents not treated with olanzapine. All patients were receiving either inpatient or day hospital care and there were no significant differences in weight [140].

In terms of case series, Leggero and colleagues [142] reported on 13 young patients (age 9.6 to 16.3 years) treated with a mean dose of 4.13 mg daily of olanzapine. Significant improvements were seen in weight, functioning, eating disorder symptoms and hyperactivity. Similarly, Swenne and Rosling [141] reported on 47 adolescents with AN treated with a mean dose of 5.1 mg daily. A mean weight gain of 9 kg was noted. The patients were treated for a mean of 228 days with olanzapine and were followed for three months following medication discontinuation. Biochemical side effects were closely monitored and were felt to be more related to refeeding processes than to medication [141].