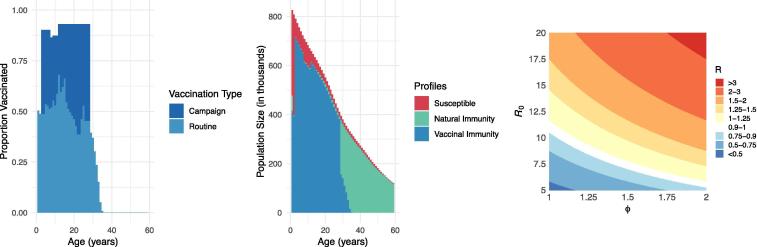

Fig. 3.

Benefits of modeling to understand outbreak risk. (A) From readily available data, we can derive the proportions vaccinated by age cohort; here we see the vaccination profile as of 2018 in Madagascar vaccinated by routine (WHO-UNICEF estimates) and campaign (administrative coverage reported to WHO) activities. It is important to note that administrative coverage data typically over-estimate campaign coverage, and a post-campaign coverage survey is preferred when available [12]. (B) To infer population susceptibility prior to the 2018–19 measles outbreak, we can use modeling to estimate age profiles of measles susceptibility, natural immunity, and vaccinal immunity; here we portray the epidemiologic profile of the Malagasy population estimated using pseudo-dynamic transmission models [16]. (C) Incorporating estimates of susceptibility heterogeneity, we can use modeling to estimate outbreak risk. Here we demonstrate the estimated measles R in the Malagasy population in 2018 across different assumed R0 values (5–20) and susceptibility clustering levels (defined as the relative probability of infected individuals coming into contact with susceptible individuals, e.g., ϕ = 1 in a homogeneously mixing population and ϕ = 2 when infected individuals are twice as likely to contact susceptible individuals) [47].