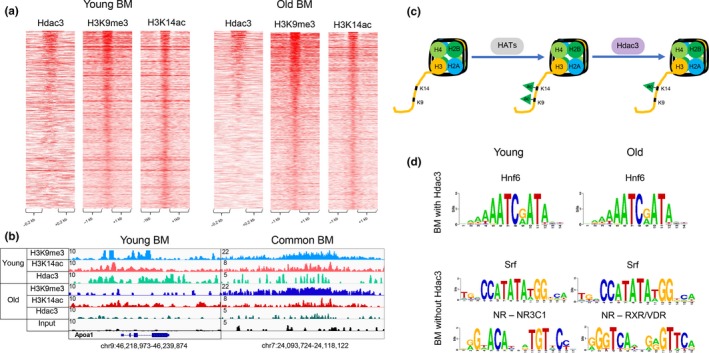

Figure 4.

Hdac3 occupies H3K9me3/H3K14ac bivalent regions. (a) Heatmaps showing Hdac3, H3K9me3, and H3K14ac ChIP‐Seq signal at bivalent regions of young (left panel) and old (right panel) livers. A subset of bivalent regions is bound by Hdac3 in both young and old livers. (b) Examples of genomic regions showing the bivalent region bound by Hdac3 in young livers (chr9:46,218,973–46,239,874) and common to young and old livers (chr7:24,093,724–24,118,122). Magnitude of the ChIP‐Seq signal is shown on y‐axis. (c) Model implicating histone deacetylase, Hdac3, in establishment of bivalent mark. First, a histone acetyltransferase acetylates both H3K9 and H3K14, known to be acetylated together in many regions, followed by deacetylation of H3K9 residue by Hdac3, allowing for its subsequent tri‐methylation. (d) Overrepresented motifs in the bivalent regions with and without Hdac3 binding in young and old livers, identified by PscanChIP. Onecut/Hnf6 motifs were enriched in both young and old bivalent regions bound with Hdac3 livers (p‐values < 4.3E‐38 and 6.8E‐7, respectively). In contrast, motifs in dually marked regions without Hdac3 occupancy included Srf in both young and old livers (p‐values < 0.001 and 6.1E‐6) and several nuclear receptors (young NR3C1, p‐value < 7.4E‐7; old RXRA: VDR, p‐value < 0.0148). ChIP‐Seq data for Hdac3 (Bochkis et al., 2014) and H3K9me3 (Whitton et al., 2018) are from our previous studies