Abstract

Background:

Assessing aspects of intersections that may affect the risk of pedestrian injury is critical to developing child pedestrian injury prevention strategies, but visiting intersections to inspect them is costly and time-consuming. Several research teams have validated the use of Google Street View to conduct virtual neighborhood audits that remove the need for field teams to conduct in-person audits.

Methods:

We developed a 38-item virtual audit instrument to assess intersections for pedestrian injury risk and tested it on intersections within 700 meters of 26 schools in New York City using the Computer Assisted Neighborhood Visual Assessment System (CANVAS) with Google Street View imagery.

Results:

Six trained auditors tested this instrument for inter-rater reliability on 111 randomly selected intersections and for test-retest reliability on 264 other intersections. Inter-rater kappa scores ranged from −0.01 to 0.92, with nearly half falling above 0.41, the conventional threshold for moderate agreement. Test-retest kappa scores were slightly higher than but highly correlated with inter-rater scores (spearman rho=0.83). Items that were highly reliable included presence of a pedestrian signal (K=0.92), presence of an overhead structure such as an elevated train or a highway (K=0.81), and intersection complexity (K=0.76).

Conclusions:

Built environment features of intersections relevant to pedestrian safety can be reliably measured using a virtual audit protocol implemented via CANVAS and Google Street View.

Keywords: cities, data collection, Google Street View, pedestrian environment, urban health

Introduction

Several research teams have validated the use of Google Street View to conduct virtual neighborhood audits that remove the need for field teams to conduct in-person audits.(1–5) Pedestrian safety is a research area that can benefit from such virtual audits. Nearly 40,000 child pedestrians in the United States are injured each year, and nearly 400 die from their injuries.(6) Interventions like the Safe Routes to School program (7–9) that focus on changes to the built environment like improving lighting, adding speed bumps, or maintaining pavement markings can substantially improve pedestrian safety, (10) yet evidence remains limited on which approaches and interventions are most effective, and in what contexts.(10,11) This gap is in part due to the cost and effort of conducting site visits to identify and assess factors at individual intersections (15).

In this study, we report on a comprehensive approach to street audits using CANVAS, improving on prior audits in three ways. First, while audit methods to date have generally focused on street segments, in this study we establish a framework to assess microscale characteristics of intersections, which are the focal point of most interventions to prevent pedestrian collisions. Second, we focus primary data collection specifically on aspects of the environment thought to affect injury risk, including intersection complexity and street lighting. Finally, we sample intersections near New York City schools that received Safe Routes to Schools interventions,(16) thus focusing on locations with both high pedestrian density and municipal support for pedestrian injury prevention.

This study presents the development of the protocol and initial reliability results for a CANVAS-based audit of intersections near 26 schools in New York City that received interventions between 2005 and 2009.

Methods

The CANVAS system and the audit team

CANVAS is a web application accessible from the public Internet and designed for use with a dual-monitor computer system (6). The audit team in this study was comprised of 6 auditors with academic affiliations ranging from undergraduate to associate professor. This auditor team worked from diverse locations, met weekly as a group using web video conferencing technology, and used a wiki website to track decisions and focus discussions.

Audit unit

Because our audit focused on street conditions rather than neighborhood conditions, we chose the intersection as the unit of primary data collection, a decision (15,20) that has implications both for the audit protocol and for the audit location selection, as detailed below.

Intersection audit protocol

After using Street View with a pilot sample of 20 intersections selected from around New York City, the four-member study design team (CJD, KWM, AGR, SJM) developed an audit protocol that standardized the boundaries of the auditable area for a given intersection. We defined the street intersection as an area where multiple street segments overlapped such that cars and pedestrians moving in multiple directions would interact with each other, plus the distance down each street segment that could be reached within two mouse clicks in the Street View interface. We chose this definition to include not only built environment features in the space where pedestrians and cars interact with one another (e.g. crosswalks, signals, and lighting), but also features experienced by drivers as they immediately approached this overlapping space that could affect the risk of a collision (e.g. billboards/distractions, on-street parking, proximity to playgrounds).

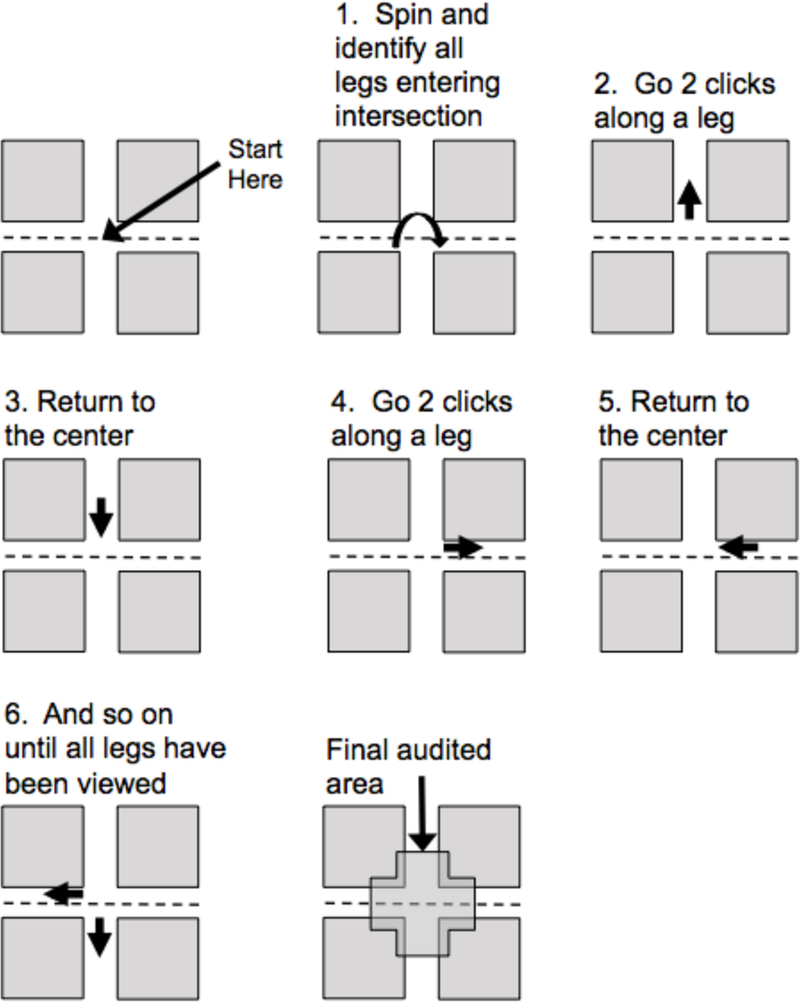

Specifically, we instructed auditors to:

-

1)

Spin 360 degrees around the starting point (typically the center of the intersection) and identify all street segments forming the intersection at that point

-

2)

For each identifiable street segment, click on the Street View interface arrow leading away from the intersection twice, then turn 180 degrees and return to the intersection center

-

3)

When moving two clicks down an intersection leg resulted in identifying more legs, include that leg in set of segments to move two clicks down

-

4)

When all segments have been explored two clicks, consider the union of the space passed in steps 1, 2 and 3 to constitute the intersection

This spatial protocol is illustrated in Figure 1. As the street intersection was defined as the union of these spaces, an intersection was scored as having a feature if the feature was present in any part of the intersection. Data were not collected separately for each street segment entering the intersection. For example, if a bus stop was present on one street segment entering an intersection, we recorded that the intersection unit had a bus stop.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the intersection-based audit protocol

Intersection sample

Using records obtained from the New York City Department of Transportation, we identified 26 schools that had completed interventions in the five boroughs of New York City as of January 2009 (10). We picked schools selected for Safe Routes to Schools interventions for two reasons: First, these schools were initially chosen by the New York City Department of Transportation because of their elevated pedestrian injury rates, so these intersections are of particular public health interest. Second, because interventions included targeted pedestrian environment enhancements, we anticipated that intersections near these schools might be enriched in features such as curb extensions that would be of particular interest to injury prevention researchers.

Once the schools were selected, using Street Centerline data (February 2018) from the New York City Department of City Planning, we identified latitude and longitude of all intersections joining 3 or more street segments within a 700-meter buffer of the 26 selected schools (n=3,786). We chose 700 meters because it represents about 10 minutes walking. Next, for each latitude/longitude value, we used CANVAS to identify the nearest Google Street View image. All latitude/longitude coordinates in our sample had Street View imagery within 50m. In practice, because some intersections were within the buffer zones of more than one selected school, assigning each intersection by school resulted in our auditing some intersections not in our formal reliability test subsample more than once (n=1,087). In all, we selected 2,699 unique locations for audit. During the audit, we excluded a further 108 intersections that did not represent vehicular intersections. The vast majority of these were intersections of streets with footpaths in high-rise housing complexes, which were included in the initial sample because footpaths were marked as road segments in the centerline file we used to identify intersections. Other non-intersections included highway overpasses and intersections of park footpaths with each other or a roadway. Our reliability analysis focuses on two subsamples of the remaining 2591 unique intersections, as detailed below

Audit Instrument development

Our study design team reviewed and selected audit items from the Irvine-Minnesota Inventory (7) and the Pedestrian Environment Data Scan (8). We used both prior virtual audit validation results (6, 18) and domain expertise to select items. We augmented these items with six new items. Our initial explorations suggested that the geometry of the intersection might strongly affect the risk to pedestrians. As a result, we developed an item aimed at classifying the geometry, asking “What type of intersection is this?” and offering six responses: 1) simple 3-way T; 2) simple 3-way Y; 3) simple 4-way; 4) offset 4-way; 5) traffic circle or rotary; or 6) complex intersection, where complex intersection was defined as anything that could not adequately be defined by the others. Overhead imagery of several complex intersections, highlighting the geometric features that may make safely traversing these intersections more cognitively challenging for drivers or pedestrians, is shown in eAppendix 1. In the analysis phase, we found that 3-way Ys, offset 4-ways, and traffic circles were uncommon. As a result, to compute reliability, we recoded 3-way T and 3-way Y to ‘3-way’, simple 4-way and offset 4-way to ‘4-way’ and traffic circle or complex to ‘complex’.

The remaining five new items were less complicated. Two assessed intersection characteristics: 1) How unsafe does the most dangerous potential crossing at this intersection feel? (Response choices: Very dangerous/Somewhat dangerous/About average/Somewhat safe/Very safe), and 2) Is there any physical structure spanning the intersection (ex: overpass, elevated train tracks), or within 2 clicks of intersection? (Response choices: Yes/No). We also developed two items representing environmental factors potentially affecting risk to pedestrians but not assessed in the prior inventories: 1) Are there any restaurants, delis/convenience stores, bars, or other alcohol retailers? (Response choices: Yes/No), and 2) Are there street lights present? (Response choice: Yes/No). Finally, we developed one item to explore the potential to assess built environment change in future audits: What is the year of the oldest image available?

For some audit items, an intersection unit may have multiple variants of the built environment feature being assessed. For example an intersection may have a bus stop with shelter along one leg and a bus stop with just a sign along another. For audit items for which multiple variants might be present, we added multiple as a response option.

Training

To train auditors, we identified intersections that were within 700m of New York City schools that did not receive interventions but were not within 700m of any schools that did. From that list, we randomly selected a set of 10 intersections for all 6 auditors to audit. CANVAS automatically computes Fleiss’s kappa scores for each item in real-time, and the study managers (SJM and AGR) used these scores to determine which items were least reliable and which intersections were the sources of item unreliability. This process was repeated until the study manager team deemed that further improvement of reliability through training was unlikely. In practice, this occurred after 3 sets of 10 intersections. Instructive training slides are available in eAppendix 2.

Audit process

When training was complete, we allocated a queue of intersections to each auditor. When auditors were unsure how to make decisions (e.g. are lines painted on the roadway considered a curb extension; see eAppendix 3 for some examples), they logged the intersection in question on a wiki webpage set up to support the project. The audit team held weekly web conference meetings to discuss the logged intersecrtion features and resolve disagreements. As appropriate, intersections whose characteristics illustrated ambiguous features were added to the wiki page on the relevant audit item.

Inter-rater reliability assessment

We randomly selected 5% of all intersections (n=188) to be rated by all auditors. Eight of these randomly selected intersections fell within overlapping school buffer areas and were selected into the reliability subsample twice. In these eight instances, one set of duplicate audits were randomly selected and deleted. One hundred and eleven of the remaining 180 unique intersections (62%) were audited by 6 auditors; an additional 67 (37%) were audited by all but one of the auditors. We used the 111 intersections audited by all 6 auditors for our primary reliability analysis. Figure 2 is a flow chart illustrating the selection process. eFigure 4 maps these intersections.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of intersection selection process

Most audit items used nominal categorical responses; for these, we computed Fleiss’s kappa scores, which treats auditors as selected from a larger pool of possible auditors. For ordinal audit items we computed a two-way intra-class correlation (ICC) consistency statistic for multiple auditors. As a sensitivity analysis, we repeated the reliability analysis on all 180 unique intersections as rated by 5 auditors. To assess the reliability impact of imagery updates during the audit, we re-computed kappa and ICC statistics for a subset of intersections having an identical image date for all six auditors (n=90). All computations used the R for Windows (Vienna, Austria) ‘irr’ package

Test retest reliability assessment

Our sampling procedure inadvertently selected all intersections surrounding four schools for audit twice. We completed the audit before realizing the error had occurred. Because of this mistake, some auditors audited the same intersection more than once. We assessed test-retest reliability by computing Cohen’s kappa for 264 unique intersections that the same auditor audited twice.

Final item selection

Finally, we considered reliability results and substantive interest to categorize items into one of three categories: core (reliable within New York), extended (not proven reliable within New York, but potentially reliable in contexts where the assessed item showed more variability) and dropped (not likely to be reliable enough for future audits in any context). We considered the core items to represent the final audit instrument, and the core plus extended items to represent the audit instrument future audits in other geographic contexts might consider.

No human subjects were involved in the research.

Results

Audit time

Auditing began in June 2018 and concluded in November 2018. Because auditors had different amounts of time available to audit intersections and proceeded through their assigned intersections at different speeds, we reassigned tasks among auditors during the audit period. The number of intersections rated by each auditor ranged from 402 and 1015 intersections. As data collection progressed, the time required to complete an intersection audit decreased. During the data collection phase covering the first 5 schools, each intersection took about 5 minutes to rate, with the fastest auditor completing intersections in a median of 3 minutes and 33 seconds and the slowest requiring a median of 6 minutes and 28 seconds. For the final five schools, the fastest auditor required a median of 1 minute and 43 seconds per intersection while the slowest required 5 minutes and 25 seconds. In all, about 350 person-hours were spent auditing intersections in CANVAS.

Item frequencies

Assessed items varied substantially in frequency across the full sample (Table 1). About half of all intersections were simple four-way (n=1,249, 49%), with complex intersections (n=296, 12%) and three-way (n=729, 28%) making up most of the others. Few intersections had no crosswalks at all (n=291, 11%), though of those with any crosswalks, a good proportion did not have crosswalks at all possible crossings (n=1014, 39% of all intersections). About a quarter of intersections (n=638, 25%) had bus stops on at least one leg. Outdoor dining areas, scenic/landmark views, and traffic calming devices other than curb extensions were extremely rare (<=2%), whereas sidewalks, streetlights, and on-street parking were extremely prevalent (>98%).

Table 1.

Frequencies of responses to 38 Intersection audit items, audit of New York City, 2018 (n=2591 unique intersections; one randomly sampled audit per intersection, where there was >1 audit).

| Item Description | Item Level | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Restaurants, delis/convenience stores, bars, or other alcohol retailers | Unknown | 2 | 0.1 |

| Yes | 981 | 38 | |

| No | 1588 | 62 | |

| Street lights | Unknown | 1 | 0 |

| Yes | 2528 | 98 | |

| No | 42 | 1.6 | |

| Type of intersection (3 categories) | Unknown | 25 | 1 |

| 3 way | 729 | 28 | |

| 4 simple | 1249 | 49 | |

| All other | 568 | 22 | |

| Subjective ranking of crossing danger level | Somewhat or very dangerous | 1049 | 41 |

| Average or somewhat safe | 1519 | 59 | |

| Overhead physical structure (e.g. overpass, elevated train tracks) | Unknown | 1 | 0 |

| Yes | 170 | 7 | |

| No | 2400 | 93 | |

| Earliest image year available | Unknown | 4 | 0.2 |

| 2007- | 713 | 28 | |

| 2008 | 93 | 3.6 | |

| 2009 | 271 | 11 | |

| 2010 | 121 | 5 | |

| 2011 | 700 | 27 | |

| 2012 | 450 | 18 | |

| 2013 | 108 | 4.2 | |

| 2014 | 41 | 1.6 | |

| 2015 | 6 | 0.2 | |

| 2016 | 31 | 1.2 | |

| 2017+ | 33 | 1.3 | |

| Significant image change from one click to another | Unknown | 3 | 0.1 |

| Yes | 298 | 12 | |

| No | 2270 | 88 | |

| Any bicycle lanes | Unknown | 3 | 0.1 |

| Yes | 394 | 15 | |

| No | 2174 | 85 | |

| On-road, paint-only bicycle lanes | Not Applicable | 2174 | 85 |

| Unknown | 3 | 0.1 | |

| Yes | 352 | 14 | |

| No | 42 | 1.6 | |

| On-road, physically separated bicycle lanes | Not Applicable | 2174 | 85 |

| Unknown | 3 | 0.1 | |

| Yes | 43 | 1.7 | |

| No | 351 | 14 | |

| Off-road bicycle lanes | Not Applicable | 2174 | 85 |

| Unknown | 3 | 0.1 | |

| Yes | 19 | 0.7 | |

| No | 375 | 15 | |

| Outdoor dining areas (cafes, outdoor tables at coffee shops or plazas, etc.) | Unknown | 3 | 0.1 |

| Yes | 54 | 2.1 | |

| No | 2514 | 98 | |

| Type of on street parking | Unknown | 1 | 0 |

| Parallel | 2445 | 95 | |

| Diagonal | 9 | 0.4 | |

| Multiple | 81 | 3.2 | |

| None | 35 | 1.4 | |

| Any on street parking | Any | 2535 | 99 |

| None | 35 | 1.4 | |

| Visible billboards | Unknown | 4 | 0.2 |

| Yes | 175 | 6.8 | |

| No | 2392 | 93 | |

| Pedestrian crossing marked or unmarked | Unknown | 3 | 0.1 |

| All | 1233 | 48 | |

| Some | 1014 | 39 | |

| None | 291 | 11 | |

| Not applicable | 30 | 1.2 | |

| Total lanes for cars (include turning lanes but not including parking lanes) | Unknown | 12 | 0.5 |

| 3- | 151 | 5.9 | |

| 4 | 268 | 10 | |

| 5 | 205 | 8 | |

| 6 | 733 | 28 | |

| 7 | 127 | 4.9 | |

| 8 | 428 | 17 | |

| 9 | 86 | 3.3 | |

| 10 | 161 | 6.3 | |

| 11 | 79 | 3.1 | |

| 12+ | 321 | 12 | |

| Significant open view of landmark or scenery | Unknown | 3 | 0.1 |

| Yes | 50 | 1.9 | |

| No | 2518 | 98 | |

| Parks, playgrounds or fields | Unknown | 4 | 0.2 |

| Yes | 300 | 12 | |

| No | 2267 | 88 | |

| Other public space | Unknown | 3 | 0.1 |

| Yes | 171 | 6.7 | |

| No | 2397 | 93 | |

| Type of crosswalks if marked (painted, zebra, surface, other) | Unknown | 1 | 0 |

| Painted lines | 636 | 25 | |

| Zebra stripes | 1452 | 56 | |

| Different road surface | 7 | 0.3 | |

| Multiple patterns | 154 | 6 | |

| Other | 4 | 0.2 | |

| Not marked at all | 317 | 12 | |

| Type of traffic signal | Unknown | 4 | 0.2 |

| Traffic signal | 1179 | 46 | |

| Stop sign | 1061 | 41 | |

| Yield sign | 7 | 0.3 | |

| Signal and stop | 45 | 1.8 | |

| Signal and yield | 2 | 0.1 | |

| Other multiple | 15 | 0.6 | |

| None | 258 | 10 | |

| Abandoned lot | Unknown | 3 | 0.1 |

| Yes | 105 | 4.1 | |

| No | 2463 | 96 | |

| Sidewalk continuity | Unknown | 3 | 0.1 |

| Complete | 2489 | 97 | |

| Incomplete | 72 | 2.8 | |

| 7 | 0.3 | ||

| Road condition | Poor | 168 | 6.5 |

| Fair or better | 2400 | 93 | |

| Parking lot spanning building frontage | Unknown | 2 | 0.1 |

| Yes | 96 | 3.7 | |

| No | 2467 | 96 | |

| 6 | 0.2 | ||

| Pedestrian signal | Unknown | 2 | 0.1 |

| Yes | 1203 | 47 | |

| No | 1366 | 53 | |

| Median or island for pedestrian refuge | Unknown | 2 | 0.1 |

| Yes | 414 | 16 | |

| No | 2155 | 84 | |

| Curb extension | Unknown | 3 | 0.1 |

| Yes | 135 | 5.3 | |

| No | 2433 | 95 | |

| Chicane | Unknown | 3 | 0.1 |

| Yes | 3 | 0.1 | |

| No | 2565 | 100 | |

| Choker | Unknown | 3 | 0.1 |

| Yes | 8 | 0.3 | |

| No | 2560 | 100 | |

| Speed bump | Unknown | 3 | 0.1 |

| Yes | 28 | 1.1 | |

| No | 2540 | 99 | |

| Rumble strip | Unknown | 3 | 0.1 |

| No | 2568 | 100 | |

| Other traffic calming device or design (e.g. raised crosswalk, different road surface) | Unknown | 3 | 0.1 |

| Yes | 28 | 1.1 | |

| No | 2540 | 99 | |

| Bike route signs, bike crossing warnings, or sharrows | Unknown | 4 | 0.2 |

| Yes | 263 | 10 | |

| No | 2304 | 90 | |

| Commercial garbage bin or dumpster | Unknown | 3 | 0.1 |

| Yes | 98 | 3.8 | |

| No | 2470 | 96 | |

| Tree shade level | Unknown | 2 | 0.1 |

| None or a few | 1934 | 75 | |

| Many or dense | 635 | 25 | |

| Any bus stop | Any bus stop | 638 | 25 |

| No bus stop | 1925 | 75 | |

| Type of sidewalk or path | Unknown | 1 | 0 |

| Footpath (unpaved) | 5 | 0.2 | |

| Sidewalk | 2547 | 99. | |

| Pedestrian street (closed to cars) | 6 | 0.2 | |

| None | 12 | 0.5 | |

Item reliability

Twelve categorical items had Fleiss’s kappa scores for inter-rater reliability above 0.6, which is conventionally the threshold for ‘substantial’ agreement and an additional seven had scores between 0.4 and 0.6, in the range considered ‘moderate’ (Table 2). Items we assessed reliably included presence of bike lanes (K=0.84), presence of a median (K=0.74) and intersection complexity (K=0.76). In general, audit items with low Kappa scores assessed low prevalence intersection features. For instance, the presence of other traffic calming devices had a kappa of −0.01, but traffic calming devices were not present in 99% of intersections. As expected, test retest reliability (Table 2) was generally better than inter-rater reliability, but the two reliability types were strongly correlated (Spearman’s rho = 0.83). Items with notably higher test-retest reliability scores include the presence of curb extensions (K=0.35 inter-rater, K=0.84 test-retest), and significant views (K=0.11 inter-rater, K=0.57 test-retest). These items may benefit from further auditor training.

Table 2.

Kappa scores for 38 items assessed by 6 auditors on 111 intersections, and test retest kappa scores for 264 paired intersections in New York City, 2018

| Item | Interrater Reliability 6 auditors, n=111 |

Test-Retest Matched Pairs, n=264 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kappa (Fleiss) |

95% CI | Kappa (Cohen) |

95% CI | |

| Restaurants, delis/convenience stores, bars, or other alcohol retailers | 0.78 | (0.71, 0.85) | 0.80 | (0.72, 0.87) |

| Street lights | 0.03 | (−0.02, 0.09) | −0.01 | (−0.01, 0) |

| Type of intersection | 0.76 | (0.70, 0.83) | 0.87 | (0.81, 0.92) |

| Subjective ranking of crossing danger level: somewhat or very dangerous | 0.24 | (0.16, 0.33) | 0.56 | (0.46, 0.67) |

| Overhead physical structure (e.g. overpass, elevated train tracks) | 0.81 | (0.62, 1.00) | 0.85 | (0.72, 0.99) |

| Significant image change from one click to another | 0.16 | (0.07, 0.26) | 0.26 | (0.09, 0.43) |

| Any bicycle lanes | 0.84 | (0.75, 0.92) | 0.83 | (0.74, 0.91) |

| On-road, paint-only bicycle lanes | 0.82 | (0.74, 0.92) | 0.80 | (0.72, 0.88) |

| On-road, physically separated bicycle lanes | 0.82 | (0.72, 0.91) | 0.81 | (0.73, 0.90) |

| Off-road bicycle lanes | 0.83 | (0.76, 0.91) | 0.83 | (0.75, 0.91) |

| Outdoor dining areas (cafes, outdoor tables, etc) | 0.05 | (−0.03, 0.14) | 0.43 | (0.17, 0.71) |

| Type of on street parking | 0.49 | (0.32, 0.69) | 0.75 | (0.56, 0.94) |

| Any on street parking | 0.00 | (0, 0) | 0.50 | (−0.11, 1.00) |

| Visible billboards | 0.40 | (0.21, 0.63) | 0.68 | (0.55, 0.83) |

| Pedestrian crossing marked or unmarked | 0.73 | (0.66, 0.80) | 0.75 | (0.67, 0.83) |

| Significant open view of landmark or scenery | 0.11 | (0, 0.24) | 0.67 | (0.46, 0.89) |

| Parks, playgrounds or fields | 0.57 | (0.40, 0.76) | 0.82 | (0.73, 0.92) |

| Other public space | 0.37 | (0.17, 0.59) | 0.65 | (0.49, 0.82) |

| Type of crosswalks if marked (style, 6 categories) | 0.78 | (0.71, 0.85) | 0.82 | (0.74, 0.89) |

| Type of traffic signal | 0.81 | (0.75, 0.87) | 0.86 | (0.80, 0.92) |

| Abandoned lot | 0.26 | (0.10, 0.44) | 0.57 | (0.27, 0.90) |

| Sidewalk continuity | 0.14 | (0.02, 0.26) | 0.24 | (−0.13, 0.67) |

| Road condition | 0.16 | (0.10, 0.22) | 0.34 | (0.24, 0.45) |

| Road condition: poor | 0.29 | (0.17, 0.42) | 0.37 | (0.18, 0.56) |

| Parking lot spanning building frontage | 0.07 | (0.02, 0.12) | 0.45 | (0.11, 0.84) |

| Pedestrian signal | 0.92 | (0.87, 0.97) | 0.88 | (0.82, 0.94) |

| Median or island for pedestrian refuge | 0.74 | (0.66, 0.83) | 0.90 | (0.83, 0.97) |

| Curb extension | 0.35 | (0.28, 0.44) | 0.84 | (0.73, 0.96) |

| Chicane | Never observed in reliability sample | |||

| Choker | 0.00 | (0, 0) | 0.00 | (0, 0) |

| Speed bump | 0.57 | (0.12, 1.00) | 0.00 | (0, 0) |

| Rumble strip | Never observed in reliability sample | |||

| Other traffic calming device or design (e.g. raised crosswalk, different road surface) | −0.01 | (−0.01, 0) | −0.01 | (−0.02, 0) |

| Bike route signs, bike crossing warnings, or sharrows | 0.42 | (0.30, 0.55) | 0.64 | (0.52, 0.77) |

| Commercial garbage bin or dumpster | 0.14 | (0, 0.31) | 0.36 | (0.09, 0.64) |

| Tree shade level | 0.27 | (0.20, 0.34) | 0.51 | (0.38, 0.64) |

| Any bus stop | 0.57 | (0.48, 0.66) | 0.72 | (0.62, 0.82) |

| Type of sidewalk or path | 0.00 | (0, 0) | 0.00 | (0, 0) |

Intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) for ordinal measures are reported in Table 3. Notably, the item assessing the auditor’s holistic sense that the intersection was safe showed only moderate inter-rater reliability (ICC=0.40) whereas earliest image date (ICC=0.82) and total lanes for cars (ICC=0.81) were much more reliable.

Table 3.

Kappa scores for 3 ordinal items assessed by 6 auditors on 111 intersections, New York City, 2018

| Item | ICC | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Subjective ranking of crossing danger level | 0.40 | (0.31, 0.49) |

| Earliest image year available | 0.82 | (0.77, 0.86) |

| Total lanes for cars (include turning lanes but not including parking lanes) | 0.81 | (0.76, 0.86) |

Sensitivity analyses

Inter-rater reliability scores in the sensitivity analysis including only five auditors but more intersections (n=178) did not differ substantially from the primary six-auditor sample. Likewise our sensitivity analysis for intersections having identical image dates across all six auditors (n=90) did not differ meaningfully from the full six-auditor sample. Full results are in presented in eAppendix 5.

Final instrument selection

Our review of the item reliability identified twenty items as composing the core audit instrument, six items as extended items of little use in New York but potentially useful for other audits, and eliminated nine items. All core items had inter-rater kappa scores above 0.35. The final instrument and the extended instrument items are presented in eAppendices 6 and 7.

Discussion

We developed a virtual audit instrument focused on pedestrian safety features of street intersections and tested its reliability using CANVAS with Google Street View Imagery. Our results suggest that numerous environmental factors relevant to pedestrian safety research, including crosswalk markings, pedestrian signals, and bus stops, and medians, can be assessed reliably using this instrument. Our team expended roughly 350 person-hours to audit 3,500 intersections; efficiency is a major benefit of the virtual audit approach.

Our audits focused on intersections near schools that are spread across the five boroughs of New York City. The built environments we audited range from extremely dense Lower Manhattan to Staten Island neighborhoods where urban form is similar to that of many North American suburbs. While this sample allowed us to assess reliability of items assessing features that are rare outside pedestrian-focused areas (e.g. curb extensions), it also resulted in near-ubiquity for items that are common in urban areas (e.g. streetlights). We assessed reliability using the kappa statistic, which imposes a higher penalty for inter-rater disagreement for items with very low or very high prevalence in the sample. In our study, most features that had very low kappa scores were either very rare (e.g. chicanes) or nearly ubiquitous (e.g. streetlights). By contrast, environmental features that were frequent but not ubiquitous (e.g. crosswalks) were assessed with reasonable reliability. Future work should assess areas with more heterogeneity for items receiving poor scores in our study (e.g. outer suburbs where streetlights exist in more of a patchwork).

Across all items, test-retest reliability was strongly correlated with inter-rater reliability, indicating that low item reliability was mostly determined by the cognitive and visual complexity of determining the best rating for a given item at a given location. However, test-retest reliability was somewhat higher than inter-rater reliability, indicating that improved training may be able to modestly improve inter-rater reliability.

Our instrument included two novel items of particular interest. First, we identified complex intersections, such as a diagonal street crossing through an otherwise conventional 4-way intersection, that appear to increase both traffic and cognitive load required for drivers and pedestrians to traverse the space safely. Notably, our results suggest we can assess this kind of intersection complexity reliably. Second, we hypothesized that there might be factors about an intersection that made it feel dangerous above and beyond specific features assessed objectively in the audit. However, our weak test-retest reliability results for the item assessing subjective feelings of safety suggest we cannot capture this intuition reliably.

Prior studies have assessed the pedestrian environment using Google Street View imagery. Nesoff, et al. recently reported on a related audit tool for Google Street View assessment of safety characteristics, similarly reporting being able to reliably assess presence of bus stops and pedestrian crossing signals.(22) Similarly, using virtual audit methods Hanson, et al. identified several environmental factors as being associated with injury severity (number of lanes and presence of medians), that we were able to assess reliably.(20) However, they did not report on inter-rater reliability for these items, precluding direct comparison of the present results.

Our audit used an intersection-based protocol rather than the segment-based protocol that has been more typical of neighborhood virtual audits to date (6,18,19,23). Intersection-based approaches are the most common protocol for in-person site visits to assess pedestrian safety (24) and have been used in prior virtual audits. (22) The intersection-based approach requires identifying the boundaries of intersections, which is not trivial in complex urban settings. The high reliability on items affected by intersection boundaries, such as the intersection complexity item suggest that the within-two-clicks definition of an intersection was adequate for this audit.

We encountered several challenges. When developing our sampling plan, we removed limited access highways from the street network GIS layer and treated all other intersecting street segments as intersections where pedestrians might interact with automobiles. In practice, however, we found that this definition yielded numerous locations where pedestrians were not at risk of being struck by an automobile. Examples include; places where the Manhattan Bridge onramp was elevated over the road grid, pathways in parks and housing developments that were closed to nonemergency/utility vehicular traffic, and driveways that were coded as alleys in the shape file. We designed a mechanism using a wiki page for the audit team to log these locations and reviewed them in weekly team meetings. Locations that did not meet the intersection criteria were removed from the sample.

Relatedly, our initial scan suggested that every intersection we identified by GIS had Street View imagery available. In practice, however, issues with the Street View interface precluded intersection assessment at a half-dozen locations. In several instances, we were not able to virtually enter a street segment from an intersection (a blockage), where a mouse click to move forward caused the vantage point to jump to another distant location (a teleport), or where a mouse click to move forward caused the vantage point to jump back to the center of the intersection (a loop). These glitches in the Matrix appeared to be due to technical issues with Google Street View and could be reproduced on Google Maps without using CANVAS.

A third challenge is that Street View images at a given intersection are often collected at multiple time points. For example, in a simple 4-way intersection, the camera car may pass North-South in June 2018 but not cross East-West until September 2018. Therefore, an auditor trying to collect data on the intersection may need to mentally integrate visual data collected at two (or more) time points and sometimes collected in different seasons. This is an intrinsic limitation of the virtual audit approach.(25) We instructed auditors to record characteristics of the intersection based on the most recent images, but for aspects of intersections that change frequently, temporal variability between images may have affected reliability and validity. Nonetheless, our sensitivity analysis of 90 intersections having identical image dates across all auditors was not perceptibly different. In general, we would anticipate that measurement error relating to inconsistent imagery dating would not be differential with respect to injury risk at an intersection on the small scale (e.g. within a city). This may be an issue for between-city studies, though, because Google updates Street View imagery more frequently in places people visit more often.

The consistency of imagery across audits is also a benefit of the virtual audit approach. Whereas test-retest reliability of an in-person audit cannot distinguish between changes in the underlying audit target and changes in the auditor’s perception, audits conducted within CANVAS, which captures the image date, can isolate perception changes from image changes.

Our audit team discussions and the technical tools that facilitated them substantially mitigated the impacts of audit challenges. We used a web videoconference system with screen sharing capacity and a wiki to track item scoring issues, locations that were not truly intersections, and to discuss images that were challenging to audit or simply interesting or beautiful to observe. These video conference check-ins and the wiki-based idea sharing helped not only ensure data quality by allowing discussion of issues, but also maintained morale and built camaraderie between team members. To the best of our knowledge, this audit was the first large-scale, multi-auditor Street View-based virtual audit where street auditors never met in person.

While our results are strengthened by our large sample size, the diversity of urban form we audited, and the validated CANVAS system, our results are also subject to several limitations. First, the audit locations were in proximity to schools whose pedestrian safety infrastructure had recently received upgrades. While these are areas of key public safety interest, they do not represent the pedestrian environment for children in general. Second, while the diversity of urban form we audited was a strength of this study, infrastructure in New York is more comprehensive than much of the rest of the United States. For example, 98% of our sampled intersections had overhead lighting. Finally, our six-person audit team was too small to assess any auditor-specific effects on rating (e.g. whether auditors with more driving experience see broken pavement as being more dangerous), which would be a valuable area for future research.

Conclusion

Many built environment features relevant to pedestrian safety can be reliably measured using a virtual audit protocol implemented via CANVAS and Google Street View that focuses on collecting data at street intersections.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded in part by Grant K99012868 from the National Library of Medicine, in part by Grant R01HD087460 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development, and in part by the Center for Injury Epidemiology and Prevention at Columbia, which is funded by Grant R49 CE002096 from the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Badland HM, Opit S, Witten K, et al. Can virtual streetscape audits reliably replace physical streetscape audits? Journal of Urban Health. 2010;87(6):1007–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rundle AG, Bader MD, Richards CA, et al. Using Google Street View to audit neighborhood environments. American journal of preventive medicine. 2011;40(1):94–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Griew P, Hillsdon M, Foster C, et al. Developing and testing a street audit tool using Google Street View to measure environmental supportiveness for physical activity. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2013;10(1):103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson JS, Kelly CM, Schootman M, et al. Assessing the built environment using omnidirectional imagery. American journal of preventive medicine. 2012;42(2):193–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Odgers CL, Caspi A, Bates CJ, et al. Systematic social observation of children’s neighborhoods using Google Street View: a reliable and cost-effective method. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53(10):1009–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bader MD, Mooney SJ, Lee YJ, et al. Development and deployment of the Computer Assisted Neighborhood Visual Assessment System (CANVAS) to measure health-related neighborhood conditions. Health & place. 2015;31:163–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Day K, Boarnet M, Alfonzo M, et al. The Irvine–Minnesota inventory to measure built environments: development. American journal of preventive medicine. 2006;30(2):144–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clifton KJ, Smith ADL, Rodriguez D. The development and testing of an audit for the pedestrian environment. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2007;80(1–2):95–110. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wheeler-Martin K, Mooney SJ, Lee DC, et al. Pediatric emergency department visits for pedestrian and bicyclist injuries in the US. Injury epidemiology. 2017;4(1):31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiMaggio C, Li G. Effectiveness of a safe routes to school program in preventing school-aged pedestrian injury. Pediatrics. 2013;peds–2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DiMaggio C, Brady J, Li G. Association of the Safe Routes to School program with school-age pedestrian and bicyclist injury risk in Texas. Injury epidemiology. 2015;2(1):15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiMaggio C, Frangos S, Li G. National Safe Routes to School program and risk of school-age pedestrian and bicyclist injury. Annals of epidemiology. 2016;26(6):412–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DiMaggio C, Li G. Roadway characteristics and pediatric pedestrian injury. Epidemiologic reviews. 2011;34(1):46–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Retting RA, Ferguson SA, McCartt AT. A review of evidence-based traffic engineering measures designed to reduce pedestrian-motor vehicle crashes. American journal of public health. 2003;93(9):1456–1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mooney SJ, DiMaggio CJ, Lovasi GS, et al. Use of Google Street View to assess environmental contributions to pedestrian injury. American journal of public health. 2016;106(3):462–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DiMaggio C Small-area spatiotemporal analysis of pedestrian and bicyclist injuries in New York City. Epidemiology. 2015;26(2):247–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly CM, Wilson JS, Baker EA, et al. Using Google Street View to audit the built environment: inter-rater reliability results. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2012;45(suppl_1):S108–S112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mooney SJ, Bader MD, Lovasi GS, et al. Validity of an ecometric neighborhood physical disorder measure constructed by virtual street audit. American journal of epidemiology. 2014;180(6):626–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mertens L, Compernolle S, Deforche B, et al. Built environmental correlates of cycling for transport across Europe. Health & place. 2017;44:35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanson CS, Noland RB, Brown C. The severity of pedestrian crashes: an analysis using Google Street View imagery. Journal of transport geography. 2013;33:42–53. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mooney SJ, Bader MD, Lovasi GS, et al. Street audits to measure neighborhood disorder: virtual or in-person? American journal of epidemiology. 2017;186(3):265–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nesoff ED, Milam AJ, Pollack KM, et al. Novel methods for environmental assessment of pedestrian injury: creation and validation of the Inventory for Pedestrian Safety Infrastructure. Journal of urban health. 2018;95(2):208–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bethlehem JR, Mackenbach JD, Ben-Rebah M, et al. The SPOTLIGHT virtual audit tool: a valid and reliable tool to assess obesogenic characteristics of the built environment. International journal of health geographies. 2014;13(1):52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schneider RJ, Diogenes MC, Arnold LS, et al. Association between roadway intersection characteristics and pedestrian crash risk in Alameda County, California. Transportation Research Record. 2010;2198(1):41–51. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curtis JW, Curtis A, Mapes J, et al. Using google street view for systematic observation of the built environment: analysis of spatio-temporal instability of imagery dates. International journal of health geographies. 2013;12(1):53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.