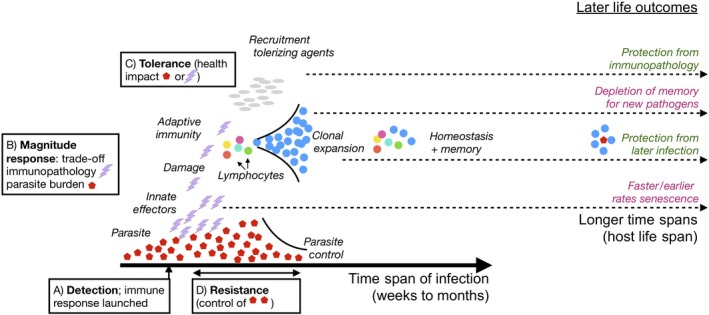

Figure 2.

Dynamics of immunity. Many immune defences are inducible, triggered once growing parasite populations (red hexagons) are detected by the pattern recognition receptors of innate immunity identifying either pathogen‐ or damage‐associated molecular patterns (x‐axis is time following parasite arrival). Innate immune effectors are then launched (purple lightning bars). For species that have adaptive immunity, lymphocytes can subsequently be recruited (coloured circles), potentially leading to amplification of specific B‐ or T‐cell clones that recognize the pathogen (blue circles). These early processes generally correspond to a phase of positive feedback. Immune defences are also associated with active downregulation, by production of repressive cytokines, such as IL10, or (for species with adaptive immunity) engagement of T‐regs promoting a tolerizing environment, that is a phase of negative feedback. Infection and the broad return to homeostasis may nevertheless harbour changes that can result in longer term effects (far right) that may negatively (purple) or positively (green) affect survival rates. Background damage shaped by immune effectors could potentially driving earlier or faster senescence; ‘learning’ by immunity will both enhance protection to previously observed pathogens, but deplete memory, reducing ability to ‘remember’ new pathogens. Finally, early infection may enable immunity to develop a broadly tolerizing environment, protecting the organism from late life immunopathology. Each of these phases of induction and return to homeostasis map onto different trade‐offs relevant for balancing costs associated with immunity (alphabetically labelled boxes correspond to labels on Figure 3). The whole process can potentially occur multiple times over the course of an individual's life span, with potential consequences for rates of senescence (see text)