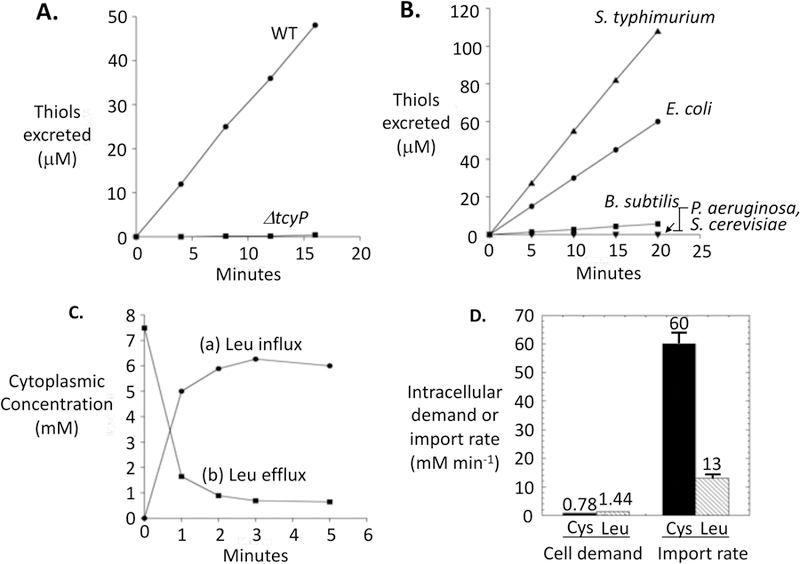

Figure 2. Cystine addition triggers profuse cysteine excretion.

(A) Excretion of thiols upon the addition of cystine (time zero) to wild-type (MG1655) and ΔtcyP (KCI1254) E. coli strains. Cells (0.1 OD600) were growing exponentially in medium containing 18 amino acids (cystine and methionine omitted). (B) Cystine was added to microbes growing in the same media as in panel A, and thiol excretion was monitored. E. coli, S. typhimurium, and B. subtilus contain TcyP homologs, whereas P. aeruginosa and S. cerevisiae do not. (C) 14C-leucine accumulation (curve a) and excretion (curve b) by E. coli. Chloramphenicol was added to cells in amino-acids-free glucose medium, and then 14C-leucine (50 μM) was added at time zero. Intracellular leucine was tracked by filtration (curve a). After 7 min, cells were washed and resuspended in medium containing 1 mM cold leucine, and efflux of 14C-leucine was tracked (curve b). Leucine was selected because E. coli lacks enzymes to catabolize it. (D) Comparison of the cellular demand for leucine and cystine (left bars) with the initial rate of influx when these amino acids are added to cells growing in amino-acid-free medium (right bars). See Experimental Methods for calculations.