Abstract

Objectives

To investigate if the treatment effect of antidepressants in patients with depression substantially varies in each patient (patient-by-treatment interaction or treatment heterogeneity), a necessary but largely unexplored prerequisite of personalised antidepressant treatment.

Design

Meta-analytic variance comparison of treatment outcome between drug arms and placebo arms of clinical trials, based on the assumption that patient-by-treatment interaction should lead to larger variances in drug arms than placebo arms. To put the results into context, we run simple simulations, assuming different definitions and rates of those who respond especially well to antidepressants.

Data sources

163 randomised, placebo-controlled trials (51 396 patients) with complete results for pre–post differences, selected from a recently published systematic review.

Analysis

Variance ratios (VRs) and coefficients of variance ratios (CVRs) of individual trials were meta-analytically combined. The analysis was repeated for classes of antidepressants and specific antidepressants.

Results

VRs (VR=1.01, CI 0.99 to 1.02) and CVRs (CVR=0.82, CI 0.80 to 0.84) of the antidepressant-treatment arms were comparable or smaller than in placebo arms. Similar results were observed for classes of antidepressants and for specific antidepressants. Our simulation analysis confirmed that equal VRs can only be obtained if they are not more than a few patients who respond slightly above average.

Conclusions

The lack of increased treatment-outcome variance in the antidepressants versus placebo groups in randomised controlled trials indicates that no or only very small subgroups of patients respond particularly well to antidepressants. Thus, the scope for personalised treatment with antidepressants seems to be limited.

Keywords: depression and mood disorders, statistics and research methods, psychiatry

Strengths and limitations of this study.

For the first time, the amount of patient-by-treatment interaction (treatment heterogeneity), a necessary prerequisite for personalised medicine, is estimated for the pharmacological treatment of depression with antidepressants.

The database is from a systematic review of published and unpublished studies and is one of the largest so far, resulting in precise estimations of the main outcomes.

The study results are important to inform further attempts in personalised (precision) medicine in psychiatry.

As with all clinical trials, it remains an open question if our results can be replicated in real-world settings, for example among psychiatric inpatients with very severe depression.

Introduction

Personalised or precision medicine, that is, applying medical interventions only to those patients known to benefit especially well to the intervention (henceforth termed ‘benefiters’), is important to increase benefits from treatment and to decrease harms. For example, if a drug with severe side effects is very effective in some patients with a specific genotype, it is crucial to know about these benefiters, because for all other patients, the risk–benefit ratio would be unfavourable. Similarly, if a drug is found to have only modest efficacy across all patients but notable side effects, then it would be important to know if there are patients (eg, those defined via a specific biomarker) who are benefiters. The latter example corresponds with the pharmacological treatment of major depression, because the average efficacy of antidepressants (ADs) is modest, corresponding to, on average, only about 2 points difference on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) between AD groups and placebo in short-term randomised controlled trials (RCTs).1–5 Put differently, according to our most recent estimate, there is about 88% overlap in distribution of depression scores between ADs and placebo at the end of acute treatment.2

Despite substantial research efforts, no predictors of treatment success with ADs were found that were robust and reliable enough for use in clinical practice.6–9 Thus, much of the variance of the treatment outcome remains unexplained so far. Sources of outcome variation include variation between treatment arms (indicating that group means differ due to efficacy of treatments, eg, ADs vs placebo), variation between patients (indicating that the outcome differs from patient to patient, independent of the treatment received), variation within patients (indicating that the outcome for the same patient differs over time due to random symptom fluctuations) and patient-by-treatment interactions (indicating that treatment effects vary from patient to patient).10 The quest for precision psychiatry, in this case—personalised AD treatment, assumes that specific patients benefit more from ADs than others, that is, assumes that there is a patient-by-treatment interaction. Ideally, this can also be explained by a plausible causal mechanism, for example, inter-individual differences in monoamine function. Investing research efforts in personalised medicine only makes sense if there truly is a patient-by-drug interaction that explains some variance in the treatment outcome. Although the field is mostly enthusiastic about personalised medicine or precision psychiatry,11 experts from various fields now start to dampen expectations and caution that personalised/precision medicine may fall short of expectations.12–14

Thus, we must remain mindful that there might be no notable subgroup of true AD benefiters and that the modest average treatment effect is the best we can hope for.15 We further need to acknowledge that RCTs are inherently limited to demonstrating patient-by-treatment interactions.10 To identify patient-by-treatment interactions, repeated period cross-over trials are necessary, but these are hardly feasible with common ADs due to delayed onset of therapeutic effect and relatively high rates of spontaneous remission. The most common trial design is the simple parallel-group trial, where patients are randomised to either ADs or placebo. However, these trials can only identify mean differences between treatment arms (ie, efficacy), whereas variation between patients, within patients, as well as patient-by-treatment interactions are part of the error term. Nevertheless, if patient-by-treatment interaction effects are present, then the variance in the treatment outcome should be increased in the drug group relative to the placebo group, because no comparable drug-by-patient interaction is present in the placebo group.10 16 17 Thus, results from RCT can inform indirectly if there might be subgroups of benefiters.

The goal of this meta-analysis was to examine whether the outcome variances between ADs and placebo differ, in order to gauge the potential of personalised/precision psychiatry for treatment with ADs.

Methods

Data

Our analysis was based on short-term RCTs of ADs for patients with unipolar major depression, reported in the most recent systematic review.18 The authors of this comprehensive study made the data available in a public repository (https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/83rthbp8ys/2). This included 522 trials (with 21 different ADs), of which 254 trials were suitable for further analysis, that is, contained information about the outcome and also included a placebo arm. Where trials had multiple treatment arms with different dosages of ADs, these arms were aggregated. Where trials compared different ADs, the data of these arms were aggregated to only have one value for the drugs in these trials, similar as in a previous publication.16 Additionally, we recorded different ADs by their class [serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), atypical ADs, and tricyclic ADs]. For 169 (67%) of studies, the pre-post mean reduction of depression scores (M) and the related SDs were available, and only the analysis for these studies is reported here. Analysis for the 85 studies (33%) where only the mean value and SD of the post-treatment depression scores were available are reported in the (online supplementary file 1,https://osf.io/98kex/files/). Several additional variables were created for sensitivity analysis (see statistical analysis).

bmjopen-2019-034816supp001.pdf (16.4KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement statement

This research was done without patient involvement. Patients were not invited to comment on the study design and were not consulted to develop patient relevant outcomes or interpret the results. Patients were not invited to contribute to the writing or editing of this document for readability or accuracy.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis

We calculated the variance ratio (VR) for each RCT and aggregated them by means of a random effect meta-analysis according to the procedure suggested by Winkelbeiner et al 16; see https://osf.io/qarvs/files/, using the metafor package in R. Because the pre–post differences were significantly associated with their SD, we repeated the analysis using the coefficient of the variance ratio (CVR). This removes the effect of expected changes in the SD due to changes in the mean.19 A VR of 1.00 suggests equal variance of AD and placebo. If the VR exceeds 1, then the variance of the AD group is larger than in the placebo group. If the CVR exceeds 1, then the increase of variance with increasing pre–post differences is stronger in the AD than in the placebo arms. Sensitivity analysis included meta-regression models with the assessment instruments, year of publication, type of publication (published vs unpublished), sample size and drop-out rates.

Simulation analysis

To bring our results into context, we also ran simulation analysis with different definitions and probabilities for benefiters. We based these simulations on an efficacy of 2 points mean difference between AD and placebo groups, as reported in a meta-analysis on the same dataset for trials using the HDRS-17 instrument.5 We assumed SD=8 and a mean difference between pre-depression and post-depression scores of 11 points in the AD group (based on rounded means of these values observed in our dataset). We used different cut-offs to define patients as benefiters, ranging from 5 to 10 points superior treatment outcome with the HDRS-17, and a proportion of 5%–50% in the AD group versus 0% in the placebo group. To simulate placebo groups, we sampled from a normal distribution with the above parameters for the placebo group (M=9, SD=8 and 5 000 000 samples). We used a similar sampling procedure for the AD group, but created benefiters by adding necessary HDRS responder points to an assumed fraction of the sample, and adding as many points to the rest of the sample to end up with the overall efficacy of 2 HDRS points.

The R-code and data of this publication are available online (https://osf.io/98kex/files/).

Results

Meta-analysis

Across all ADs, the VR was almost perfectly 1.00 with a narrow confidence interval (VR=1.01, 95% CI=0.99 to 1.02). This means that the variances in the AD and placebo groups are nearly identical (table 1). Similar findings were found for all classes of ADs (table 1) and for each individual drug (online supplementary table 2, https://osf.io/98kex/files/). There was no significant sign of heterogeneity in the meta-analyses, except for SSRIs. A closer inspection revealed that this resulted from a single outlier (see footnote in table 1).

Table 1.

Meta-analytic results for variance ratios and coefficients of variance ratio

| n | VR meta-analysis | r (M, SD) | CVR meta-analysis | ||||||||

| Trials | AD | Placebo | VR (95% CI) | p value | Q(df) | AD | Placebo | CVR (95% CI) | p value | Q(df) | |

| AD all | 169 | 32 650 | 18 746 | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.02) | 0.33 | 121.74 (168) | 0.55** | 0.52** | 0.82 (0.80 to 0.84) | 0.00 | 243.53 (168)** |

| SSRI | 89 | 13 146 | 9024 | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.04) | 0.32 | 124.94 (88)**† | 0.56** | 0.45** | 0.83 (0.80 to 0.86) | 0.00 | 137.29 (88)** |

| SNRI | 53 | 9970 | 7226 | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.03) | 0.66 | 14.26 (52) | 0.53** | 0.56** | 0.81 (0.78 to 0.84) | 0.00 | 70.37 (52)** |

| Atypical | 54 | 8780 | 6293 | 1.00 (0.97 to 1.02) | 0.69 | 17.62 (53) | 0.71** | 0.74** | 0.83 (0.79 to 0.86) | 0.00 | 61.53(53) |

| Tricyclics | 11 | 754 | 771 | 1.04 (0.95 to 1.14) | 0.40 | 15.80 (10) | −0.34 | 0.64* | 0.65 (0.58 to 0.72) | 0.00 | 6.96 (10) |

r (M, SD) is the Pearson correlation of mean pre–post differences in depression (M) and the respective SD. Q(df) is the heterogeneity index for the meta-analysis. *p<0.05, **<0.01

†This result was caused by an outlier (Study Dube 2010, NCT00420004), and after removing this study, the heterogeneity index was Q(df=87)=54.54, p=0.99.

AD, antidepressant; CVR, coefficient of variance ratio; VR, variance ratio.

bmjopen-2019-034816supp002.pdf (31KB, pdf)

For the CVR, results indicated that the increase of variance with increasing pre–post differences is less strong in AD than in placebo arms (CVR=0.82, 95% CI=0.80 to 0.84). Comparable results were found for all classes of ADs and individual drugs (table 1). The heterogeneity was statistically significant in nearly all meta-analyses of the CVR.

In the sensitivity analysis, the meta-regression models could not detect statistically significant effects for year of publication, type of publication, measurement instruments, drop out rates, and sample size (see https://osf.io/98kex/files/).

Simulation analysis

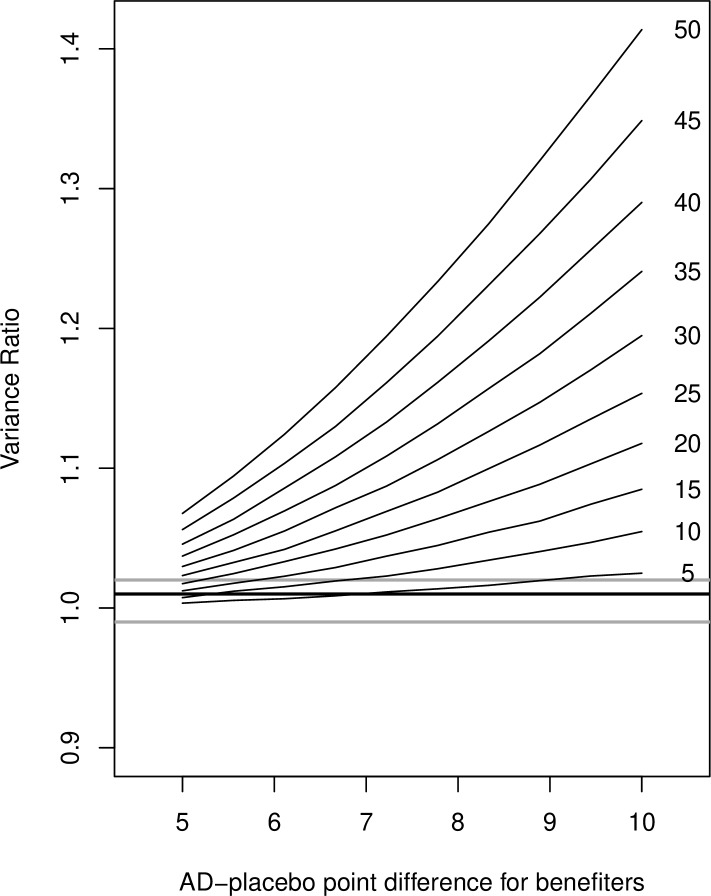

As shown in figure 1, most benefiter assumptions lead to VRs much different from those we observed in our study.

Figure 1.

Results from simulation analyses (hypothetical variance ratios) for different definitions of benefiters (x-axis) and different percentages of benefiters (individual lines with the percentages on the right side of the line). The horizontal thick line is the result from our meta-analysis (VR=1.01), the horizontal grey lines correspond with upper and lower limits of the CI of the meta-analysis (0.99–1.02). VR, variance ratio; AD, antidepressant.

However, for liberal definitions of benefiters and low rates of these benefiters, the VRs can indeed be small. For example, if there are 10% benefiters, as defined with 6 HDRS points difference to average placebo response, the VR is within the CI of our main finding (0.99–1.02).

Discussion

We found nearly identical treatment outcome variances for AD arms compared with placebo in RCTs for the acute treatment of major depression in a large database, as indicated by VRs almost perfectly being VR=1. The simplest explanation for the finding of similar variances is that there are constant treatment effects and no treatment heterogeneity, that is, no patient-by-treatment interaction effects and no specific subgroups of patients who respond particularly well to the treatment.20 Alternatively, such a subgroup of benefiters would be very small (≤10%) and the threshold to classify someone as benefiter would be low (≤6 HDRS points difference to average placebo response). To put this in context, according to anchor-based linkage studies, at least 6 points on the HDRS are necessary for a global impression of ‘minimally improved’.21 22 Consequently, the search for meaningful predictors of relative treatment response (compared with placebo) will probably fail or will at least be very difficult due to the small subgroup of weak benefiters. Therefore, the mean effect size estimate from parallel-group RCT remains the best guess for predicting treatment outcome for an individual patient. Furthermore, the results for the coefficient of variance indicated that the increase of variance associated with increasing larger pre–post differences was stronger in the placebo than the AD groups. There is no immediately plausible explanation for this finding, given that baseline severity does not predict differential treatment effects.23–25

Our findings are in line with Senn,12 who argued that exploratory post-hoc delineation of putative benefiters, such as the ‘true benefiters’ suggested by Thase et al,26 are simply statistical artefacts due to random symptom fluctuations and measurement error (see also Hengartner15). Our findings also replicate the findings for antipsychotics in the acute treatment of schizophrenia,16 and several treatments in a review of various medical interventions.17 Together, these studies indeed suggest that the promises of precision medicine may remain elusive and that the scope for personalised medicine might be smaller than previously hoped for.12 13 Given the high expectations placed in biomarker-based precision medicine, such findings will probably cause disbelief and reluctance in many advocates of this enthusiastic movement. In anticipation of such critique, we would like to address two objections that are likely to be submitted in response to this paper.

First, as recently stressed by biostatistics professor Dr Frank Harrell, to assume that there is treatment heterogeneity (ie, significant patient-by-treatment interaction) when the average treatment effect is close to zero (which is the case with ADs), would imply that there must be a large subgroup of patients where the treatment causes significant harm.27 Although it has been suggested that ADs may worsen the long-term outcome of depression in some patients,28–31 there is no evidence that they may do harm in a large subgroup of patients in short-term trials. In the absence of consistent biologically-informed patient-specific treatment effects, our best treatment estimate for ADs thus remains the average drug effect relative to placebo.27

Second, and closely related to the above argument, even after decades of massive research efforts there is no evidence of robust neurobiological and genetic predictors of differential treatment response in depression.6–9 32 Biostatistics professor Dr Stephen Senn once stated: ‘Unless patient by treatment interaction exists, it is pointless looking for gene by treatment interactions’.33 Thus, calling for more genetic and neurobiological research into differential treatment effects clearly conflicts with the current literature and will most likely fail to yield the hoped-for results.

We acknowledge the following major limitation: as Cortés et al 17 describe in their paper, equal variances are no definite proof for a lack of patient-by-treatment interactions. They hypothetically describe a situation that leads to equal variances in the treatment and in the control condition and with patient-by-treatment interactions, but this situation is highly unlikely. Furthermore, VRs of 1 are, theoretically, also possible with a small fraction of ‘super-responders’ and a specific response for all others, as highlighted in a vivid Twitter-Discussion of our paper (https://twitter.com/Martin_Ploederl/status/1188006207497363457). It can indeed be debated what assumption is more plausible: a constant treatment effect, a hypothetical fraction of super-responders or other highly specific premises. However, a small fraction of super-responders would obviously lead to non-normal distributions with notable peaks at very low levels of depression scores. This was not observed so far, to our knowledge,26 but could be further investigated with patient level data. Moreover, VRs would increase for a wide range of scenarios with varying fractions of benefiters and varying definitions of ‘benefiters’.

Another potential problem may be, as one reviewer pointed out, that the VRs did not vary much across trials, as indicated by the Q statistics, and also by the low I2 statistics. However, the main results remained the same for different estimators of heterogeneity, unweighted results or with the Knapp and Hartung adjustment (see online supplementary table 3). Furthermore, by manually increasing the value of the heterogeneity, results remained comparable. Presumably, the low between-trial heterogeneity was caused by insufficient randomisation of trials, or due to narrow and selective inclusion criteria for trial participants.34

bmjopen-2019-034816supp003.pdf (26.7KB, pdf)

In conclusion, the results of our meta-analysis suggest that there is no or at best a very small patient-by-treatment interaction. The lack of increased outcome variance in the AD versus placebo groups in parallel-group RCT indicates that no specific subgroup of patients may respond particularly well to ADs. Thus, with the ADs currently available, the scope for personalised AD treatments is probably limited and it is unlikely that precision psychiatry will succeed in finding clinical or biological predictors of differential treatment response that would account for a therapeutic effect that goes beyond a minimal clinical improvement.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Cipriani et al 18 and Winkelbeiner et al 16 for making the data and the R-code publicly available.

Footnotes

Contributors: MP and MPH were responsible for the conception and design of the study, interpretation of data, and drafting and revising the manuscript. MP performed the meta-analysis and simulation analysis. Both the authors had full access to all the data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: No ethical approval is required since our study is a secondary analysis.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available in a public, open access repository.

References

- 1. Hengartner MP. What is the threshold for a clinical minimally important drug effect? BMJ Evid Based Med 2018. 10.1136/bmjebm-2018-111056. [Epub ahead of print: 28 Aug 2018]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hengartner MP, Plöderl M. Statistically significant antidepressant-placebo differences on subjective symptom-rating scales do not prove that the drugs work: effect size and method bias matter! Front Psychiatry 2018;9 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jakobsen JC, Katakam KK, Schou A, et al. . Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus placebo in patients with major depressive disorder. A systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2017;17:58 10.1186/s12888-016-1173-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moncrieff J, Kirsch I. Efficacy of antidepressants in adults. BMJ 2005;331:155–7. 10.1136/bmj.331.7509.155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Munkholm K, Paludan-Müller AS, Boesen K. Considering the methodological limitations in the evidence base of antidepressants for depression: a reanalysis of a network meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2019;9:e024886 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Perlman K, Benrimoh D, Israel S, et al. . A systematic meta-review of predictors of antidepressant treatment outcome in major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord 2019;243:503–15. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.09.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Simon GE, Perlis RH. Personalized medicine for depression: can we match patients with treatments? AJP 2010;167:1445–55. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09111680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Widge AS, Bilge MT, Montana R, et al. . Electroencephalographic biomarkers for treatment response prediction in major depressive illness: a meta-analysis. AJP 2019;176:44–56. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17121358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tansey KE, Guipponi M, Perroud N, et al. . Genetic predictors of response to serotonergic and noradrenergic antidepressants in major depressive disorder: a genome-wide analysis of individual-level data and a meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001326 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Senn S. Mastering variation: variance components and personalised medicine. Stat Med 2016;35:966–77. 10.1002/sim.6739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fernandes BS, Williams LM, Steiner J, et al. . The new field of ‘precision psychiatry’. BMC Med 2017;15 ARTN 80 10.1186/s12916-017-0849-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Senn S. Statistical pitfalls of personalized medicine. Nature 2018;563:619–21. 10.1038/d41586-018-07535-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Joyner MJ, Paneth N. Promises, promises, and precision medicine. J Clin Invest 2019;129:946–8. 10.1172/JCI126119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Prasad V, Fojo T, Brada M. Precision oncology: origins, optimism, and potential. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:e81–6. 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00620-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hengartner MP. Scientific debate instead of beef; challenging misleading arguments about the efficacy of antidepressants. Acta Neuropsychiatr 2019;31:235–6. 10.1017/neu.2019.23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Winkelbeiner S, Leucht S, Kane JM, et al. . Evaluation of differences in individual treatment response in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. JAMA Psychiatry 2019;76 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.1530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cortés J, González JA, Medina MN, et al. . Does evidence support the high expectations placed in precision medicine? A bibliographic review. F1000Res 2019;7 10.12688/f1000research.13490.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. . Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet 2018;391:1357–66. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32802-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nakagawa S, Poulin R, Mengersen K, et al. . Meta-analysis of variation: ecological and evolutionary applications and beyond. Methods Ecol Evol 2015;6:143–52. 10.1111/2041-210X.12309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cortés J, González JA, Medina MN, et al. . Does evidence support the high expectations placed in precision medicine? A bibliographic review. F1000Res 2018;7 10.12688/f1000research.13490.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Furukawa TA, Akechi T, Azuma H, et al. . Evidence-based guidelines for interpretation of the Hamilton rating scale for depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2007;27:531–4. 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31814f30b1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Leucht S, Fennema H, Engel R, et al. . What does the HAMD mean? J Affect Disord 2013;148:243–8. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rabinowitz J, Werbeloff N, Mandel FS, et al. . Initial depression severity and response to antidepressants v. placebo: patient-level data analysis from 34 randomised controlled trials. Br J Psychiatry 2016;209:427–8. 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.173906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Furukawa TA, Maruo K, Noma H, et al. . Initial severity of major depression and efficacy of new generation antidepressants: individual participant data meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2018;137:450–8. 10.1111/acps.12886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hieronymus F, Lisinski A, Nilsson S, et al. . Influence of baseline severity on the effects of SSRIs in depression: an item-based, patient-level post-hoc analysis. Lancet Psychiat 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thase ME, Larsen KG, Kennedy SH. Assessing the ‘true’ effect of active antidepressant therapy v. placebo in major depressive disorder: use of a mixture model. Br J Psychiatry 2011;199:501–7. 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.093336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Harrell FE. Viewpoints on heterogeneity of treatment effect and precision medicine, 2019. Available: https://www.fharrell.com/post/hteview/ [Accessed 14.12.2019].

- 28. Fava GA, Offidani E. The mechanisms of tolerance in antidepressant action. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2011;35:1593–602. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.07.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. El-Mallakh RS, Gao Y, Jeannie Roberts R. Tardive dysphoria: the role of long term antidepressant use in-inducing chronic depression. Med Hypotheses 2011;76:769–73. 10.1016/j.mehy.2011.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Andrews PW, Kornstein SG, Halberstadt LJ, et al. . Blue again: perturbational effects of antidepressants suggest monoaminergic homeostasis in major depression. Front Psychol 2011;2:159 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hengartner MP, Angst J, Rössler W. Antidepressant use prospectively relates to a poorer long-term outcome of depression: results from a prospective community cohort study over 30 years. Psychother Psychosom 2018;87:181–3. 10.1159/000488802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. García-González J, Tansey KE, Hauser J, et al. . Pharmacogenetics of antidepressant response: a polygenic approach. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2017;75:128–34. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Senn S. Individual response to treatment: is it a valid assumption? BMJ 2004;329:966–8. 10.1136/bmj.329.7472.966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zimmerman M, Clark HL, Multach MD, et al. . Have treatment studies of depression become even less generalizable? A review of the inclusion and exclusion criteria used in placebo-controlled antidepressant efficacy trials published during the past 20 years. Mayo Clin Proc 2015;90:1180–6. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-034816supp001.pdf (16.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-034816supp002.pdf (31KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-034816supp003.pdf (26.7KB, pdf)