Abstract

The universal access to treatment and care for people living with HIV (PLWHIV) is still a major problem, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, where 70% of HIV-infected people live. Equally important is the fact that HIV/AIDS-related stigma is recognized to be a major obstacle to successfully control the spread of this disease. We devised a pilot project (titled “My friend with HIV remains a friend”) to fight the HIV/AIDS stigmatization through educating secondary school students by openly HIV-positive teachers. In a first step, we have measured the amount and type of stigma felt by the PLWHIV in Buea/Cameroon using the “The people living with HIV Stigma Index” from Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Gossiping and verbal insults were experienced by 90% of the interviewees, while 9% have experienced physical assaults. Using these data and material from the “Toolkit for action” from the “International Centre for the Research on Women,” the teachers educated the students on multiple aspects of HIV/AIDS and stigma. The teaching curriculum included role-plays, picture visualizations, drawing, and other forms of interactions like visits to HIV and AIDS treatment units. Before and after this intervention, the students undertook “True/False” examinations on HIV/AIDS and stigma. We compared these results with results from students from another school, who did not participate in this intervention. We were able to show that the students taking part in the intervention improved by almost 20% points in comparison to the other students. Their results did not change.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, stigmatization, UNAIDS, ICRW, Cameroon

What Do We Already Know about This Topic?

HIV/AIDS-related stigma hampers effective HIV-prevention activities and hence is a major confounder in the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

How Does Your Research Contribute to The Field?

Our research uses the results of the UNAIDS “HIV Stigma Index” questionnaire in conjunction with the “Toolkit for action” from ICRW to design a pilot project to fight HIV/AIDS Stigmatization in Buea/Cameroon. From our data we were able to show the effectiveness of our study.

What Are Your Research’s Implications toward Theory, Practice, or Policy?

We were able to show that using openly HIV-positive teachers are highly effective for reducing HIV/AIDS stigmatization. Production of a DVD has multiplied the effect. The teachers told us, that they also have learned alot about the stigmatization.

Introduction

More than 35 years after AIDS was first described, developing countries are still facing devastating health, economic, social, and developmental problems due to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) estimated that by the end of 2017, a total of 36.9 million persons were living with HIV (PLWHIV) worldwide, when compared to 29.1 million in 2001; 25.5 (70%) million are living in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).1 In Cameroon, UNAIDS estimated that by the end of 2017, 510 000 people were living with the virus. The national prevalence of HIV is 3.7% (15-49 years), 59% of the PLWHIV over 15 years are women; 29 000 people died during that year and about 340 000 children have lost a parent or both parents in Cameroon due to AIDS.1

Since the 2000 International AIDS Conference in Durban, South Africa, titled Break the silence, stigma has been recognized as a major confounder in the HIV/AIDS epidemic. “Stigma” originally was defined as a “dynamic process of devaluation that significantly discredits an individual in the eyes of others.”2 Earlier on, it was recognized as a key factor in fueling the spread of HIV.3,4 Thus, in 2008, UNAIDS reported a rather pessimistic view that HIV/AIDS-related stigma has continued to persist from the start of the epidemic 25 years ago and still constitutes one of the largest barriers in coping with it.5 Another 8 years later in 2016, the UN General Assembly Political Declaration on Ending AIDS has set out a target of eliminating HIV-related stigma and discrimination by 2020. This ambitious target follows earlier hopes that antiretroviral therapy (ART) rollout would help reduce stigma.6,7 However, public stigma—negative attitudes and beliefs that the general public hold toward PLHIV—remains a significant challenge across Africa.8,9 Moreover, ART may have mixed effects on stigma reduction, making the UNAIDS target problematic. Thus, HIV-related stigma may hinder the set goal to eliminate AIDS by 2030.7

Different forms of stigma have been described, including perceived and internalized stigma. Perceived stigma refers to PLWHIV awareness of negative social identity.10 Internalized stigma includes negative beliefs, views, and feelings toward HIV/AIDS and oneself.11 HIV/AIDS-related stigma may also be compounded by negative societal attitudes toward routes of HIV infection (eg, sex work and injection drug use) and demographic characteristics (eg, gender and ethnicity).12

Especially in developing countries, PLWHIV experience strong stigma and discrimination, which is favored by the lack of knowledge.13 As a consequence, HIV/AIDS-related stigma has enormous negative impact on social relationships, access to resources, social support network, and psychological well-being of PLWHIV. A significant greater relationship between severity of symptoms and higher levels of internal HIV/AIDS stigma in PLWHIV was found. It was reported in some studies, but not in others, that the increasing access and availability of antiretroviral treatment has reduced the prevalence of HIV/AIDS-related stigma and resulted in increased use of HIV testing and counseling services.14 Moreover, HIV/AIDS-related stigma hampers effective HIV-prevention activities (condom use; HIV test-seeking behavior, and care seeking behavior) and is a barrier to diagnosis, quality of care provided to HIV-positive patients, and the perception and treatment of PLWHIV by communities, families, and partners.5 As a result, many HIV-infected patients in low- and middle-income countries do not immediately start ART, despite being eligible for ART. In systematic reviews of SSA HIV treatment programs, just two-thirds of the eligible patients initiated ART. The findings of this review underscore the implications of stigma for decisions to start ART. Persistent HIV stigma discourages patients from starting ART because taking daily medication forces the patient to come to terms with his or her status and increases the chances of disclosure to others.15

Given this situation, it is critical that interventions that effectively reduce HIV/AIDS stigma be identified and implemented, especially in developing countries. In recent years, a number of different stigma reduction programs have been implemented with success, which are summarized in the following reviews.16-18

We piloted a novel project to fight HIV/AIDS stigmatization through educating secondary school students in Cameroon, using an innovative approach: Openly, HIV-positive teachers took our results of the UNAIDS stigma questionnaire as a basis for their teaching in combination with the material from International Centre for the Research on Women (ICRW).

Materials and Methods

Study Setting

We conducted this interventional study in Buea, the capital city of the South West Region of Cameroon. Buea is a city with a population of over 86 000 people and has a local HIV infection rate of 5.7%. The local HIV/AIDS treatment center is supporting about 2000 PLWHIV, three-quarters of whom are females. We decided to work with secondary school students since they are young and now considering themselves as the change agents of today while preparing themselves for the future. Their opinions are more likely to change upon education than the opinions of adults. To conduct this pilot project, we selected 2 secondary schools: the Government High School, Bokwango, as our Test School and the Government Bilingual Grammar School, Molyko, as our Control School. From each school, 100 students between the ages of 16 and 18 years were randomly selected.

Study Procedures

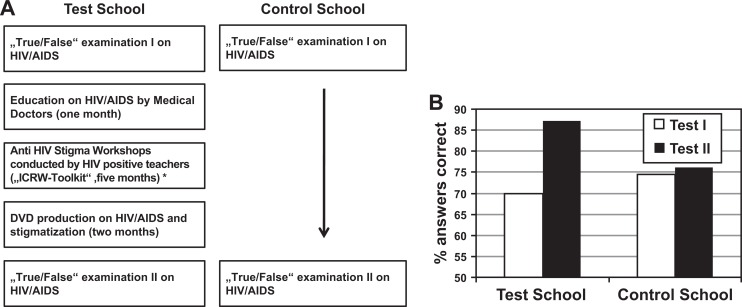

In the first phase of the project, which has been already published, we measured the HIV/AIDS-related stigma by using the “The people living with HIV Stigma Index” from UNAIDS (see Supplementary material).19 In short, we interviewed 200 PLHIV, which were randomly selected, from the HIV/AIDS treatment center in the Regional Hospital Annex Buea. These interviews were conducted by our openly HIV-positive teachers.20 In parallel to this activity, the students from the Test School were taught on multiple aspects on HIV and AIDS and stigmatization by us for 2 months (P.N.A. and V.N.M.) using lecture-style “power point” presentations. Based on our results of the “HIV Stigma Index” and the content of the “Toolkit for action” from the ICRW,21 we devised the curriculum which consists of small group work, drama, picture drawing and visualization, discussion groups, and so on (Figure 1A) for the students. Before and after this intervention, the students undertook “True/False” examinations on HIV, AIDS, and stigma to measure its potential success (see Supplementary material). We compared their results with the results of students from the Control School who did not take part in any intervention.

Figure 1.

A, Flowchart of the project. *“Name + own the problem”; “More understanding, less fear”; “Sex, morality, shame and blame”; “The family and stigma”; “Coping with stigma”; and ending with a “Moving to action module” which, for example, contains the submodule “Start with a vision—a world without stigma.” B, Results of the “True/False” examinations.

In the main phase of the project, the curriculum was taught by our teachers for a duration of 5 months. Each teacher taught a maximum of 10 students once a week for 2 hours per session. The students were taught by different teachers during the sessions. Before each session, the teachers met in a group by themselves to discuss the session of the previous week and to discuss the subject of the upcoming one. Sessions covered by the curriculum, which is set up in a modular fashion (each module contains several sub modules), included “Name+own the problem”; “More understanding, less fear”; “Sex, morality, shame and blame”; “The family and stigma”; “Coping with stigma”; and ending with a “Moving to action module” which, for example, contains the submodule “Start with a vision—a world without stigma.” The subjects of the modules are built upon each other. Special care was taken that each session was very interactive with a maximum of student participation but under the guidance and supervision of the teachers. Teachers were asked to actively involve each and every student by asking questions and for their opinions during the sessions.

Near the end of this phase, the students were asked to come up with their own story line depicting different themes on HIV/AIDS and stigma in their community. Together with a professional film crew, the students transformed these scripts into plays, which resulted in the production of a DVD. This phase ended with a post examination of the students of both the Test School and the Control School. We then compared their results with results from students from the Molyko school, which did not take part in this intervention (Figure 1B).

Ethical Consideration

We received permission from the management of the HIV/AIDS treatment center and the Regional Hospital Annex Buea as well as administrative clearance from the health authorities from the South West Region in Cameroon to conduct the interviews. In short, before starting our pilot project, we in person went to the Regional Delegation of Health and the Regional Delegation of Secondary education in Buea to discuss our proposed project with the responsible persons. Since the project was of a “pilot” character, we received an administrative clearance. We were told that we would need an official ethical approval from the Ministry of Health in the capital city of Yaounde once we roll out the project to include a multiple number of participants. The school authorities in Buea granted us permission to conduct this educational study, including naming the schools in our publications. In addition, parental consent was obtained for all the students who participated in the study.

Results

In order to determine the level and the type of stigmatization experienced by PLWHIV in Buea, we first conducted interviews using the “The people living with HIV Stigma index” questionnaire from UNAIDS. We have published these results already elsewhere.20 Briefly, we found that gossiping and verbal insults were experienced by a large majority of our interviewees (90%). Fortunately, physical assaults were reported only by a minority (9%) of the interviewed PLWHIV. Forty percent of the PLWHIV did not know the reason why they were being discriminated upon, 25% said that having HIV is shameful, and 20% believed that people are afraid of catching HIV. Internal stigma was regarded to be another major factor, as almost half of the interviewed PLWHIV felt ashamed and guilty. With respect to taking the HIV test, more than half of the interviewees were “late presenters.”20

After we have taught the students multiple aspects of HIV/AIDS and stigmatization, our teachers took over to involve them in small group work by using on the one hand the results of the questionnaire and on the other hand the “Toolkit for action.” One major focus was laid on the gossiping and the verbal insults experienced by the PLWHIV. The teachers told the students their own personal experience. Through role-plays, picture drawings, and intensive and in-depth discussions, the students were able to “relive” these situations together with the help and under the close supervision and guidance of their teachers. Another focus was the internal stigma, leaving almost half of the PLWHIV feeling ashamed or guilty. Again, through role-plays and group discussions, our teachers taught their students their experience and the techniques they are using to overcome this major hindrance for a “normal” life.

This was highly interactive, and in the course of the months, the students involved in the project brought out messages that they even used during public manifestations like the national youth day. In the next phase of the project, the students wrote scripts on the subject HIV/AIDS and stigmatization. The resulting scripts (titled “Stigma in the family”, “Stigma in the market” and “Stigma in school”) were completely played by the students themselves (duration between 5 and 15 minutes in length). A DVD was professionally produced, which we have distributed to schools throughout Buea and to interested individuals and nongovernmental organizations. With the dissemination of this DVD, the discussion on HIV/AIDS and stigma will reach out into the families and the community.

In order to measure the educational benefits and stigma reduction in this pilot project, we performed “True/False” examinations on HIV/AIDS for the students of our Test School as well as the students from the Control School before and after our intervention. While the students from the Test School improved their score between the 2 examinations dramatically by almost 20 percentage points (from 69.9 to 87.3 percentage points), the students from the Control School improved their score by only less than 2 percentage points (from 74.5 to 76.1 points; Figure 1B). The observed difference was statistically significant with a P value of 0.03 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.06-4.66). In addition, we got very positive feedback from all participants who were involved in this project. Also, our HIV-positive teachers told us that they have learned a lot, which will help them in the future.

Discussion

Apart from the still rather limited access to treatment and care for PLWHIV in SSA, HIV/AIDS-related stigma is considered to be a major problem in stemming the spread of HIV in that region. In the past, research on HIV stigma has been limited by an imbalance in attention paid to HIV uninfected versus HIV-infected people, a lack of consideration of the mechanisms through which HIV stigma impacts on people and an imprecise understanding of the psychological, behavioral, and health outcomes of HIV stigma. The first research in the late 1980s focused on assessing the extent to which HIV uninfected people felt prejudice toward and discriminated against HIV-infected people.22 As the epidemic evolved, emphasis was shifted to target PLWHIV, their experience with stigma, and the outcome.23

What can be done to reduce stigma? Education is often the first and most important step in stigma reduction and is often combined with other strategies. However, it has been shown that the influence of education is somehow limited because many stereotypes in the society as a whole are resilient to change. The effectiveness of educational approaches can be increased if combined with other approaches, such as having contact to PLWHIV and skill building. On the other hand, the support of political and religious leaders is needed in the fight against stigma. That skill building is not sufficient was shown, for example, in the 2008 Ghana demographic and health survey (GDHS), where over 95% of participants aged 15 through 49 had heard of and were aware of HIV/AIDS, but only 28% of females and 32% males demonstrated comprehensive knowledge of HIV/AIDS.24 Studies have shown that a combination of education, counseling, and contact to PLWHIV is the most promising to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma. This includes interactive components such as role-plays, games, and other experimental activities, which have been found to be effective in enhancing perspective-taking and empathy. It stimulates imaginary behavioral exposure, where participants were instructed to imagine issues and stressors that PLWHIV might face in daily situations.25-28 In addition, it was found that the effectiveness in improving attitudes toward PLHIV was significantly higher in stigma reduction programs with multiple sessions rather than only with 1 session.18

We devised a pilot project, in which we have combined these strategies to reduce HIV/AIDS-related stigma in Buea/Cameroon. We focused on the educational benefit in working with secondary school students. These are young people who are more likely to be positively influenced than adults with preset opinions. For example, in a study from Thailand involving primary schoolchildren, it was shown that there was a strong positive correlation between children’s belief that HIV could be transmitted through casual contact and their negative attitudes toward their HIV-infected peers.29

Using our results from the questionnaire, in combination with the “Toolkit for Action” from the ICRW, we devised a curriculum on HIV/AIDS stigma reduction for our secondary school students. One major focus was laid on the gossiping (experienced by 90%) and the verbal insults experienced by the PLWHIV. Gossiping and verbal insults are as painful and devastating as physical violence since especially in Africa, the social structure is centered around the family. Surprisingly, most of the time, the PLWHIV are verbally insulted by their own family members causing an even greater isolation; a number of interviewees decided not to get married, not to have sex anymore, or not to have children. With regard to taking the HIV test, most people took the test because they had symptoms that were typically AIDS related. According to the questionnaire, the disclosure of the HIV status gave most PLWHIV a great empowerment. Considering the implementation of innovative tools such as self-testing or peer-led HIV testing and support for PLWHIV may also reduce some of the stigmatization surrounding testing by normalizing it and making it more available to people who may otherwise be reluctant to test in a health-care facility.30 In addition, providing PLWHIV with differentiated models of care such as clubs or Community ART Groups in which they can access ART outside a health-care facility and receive peer support from others living with HIV is also another way of reducing stigma.31-33

In another study, the primary hypothesized factor for late HIV diagnosis was perceived HIV stigma. It was marginally significant in the multiple logistic regression analysis result. Respondents who had high perceived HIV stigma, as compared to those who had low perceived HIV stigma, were 1.7 times more likely to be diagnosed (adjusted odds ratio = 1.7, 95% CI: 1-2.89), which is similar with the result of a case-control study in South Wollo, Northeast Ethiopia.34,35

According to our data, the majority of the health-care workers, social workers, or other PLWHIV were however supportive or very supportive when they interacted with the interviewee.20 This information together with the ICRW tool kit helped us build the curriculum that our teachers used in working with the students.

In line with these results, our teachers told the students their own personal experience. Through role-plays, picture drawings, and intensive and in-depth discussions, the students were able to “relive” these situations together with the help and under the supervision and guidance of their teachers. We and others believe that this type of educational work is the strongest way to change people’s opinion and behavior. Another major factor was the internal stigma, leaving almost half of the PLWHIV feeling ashamed or guilty. To fight internal stigma, a novel program incorporating “Inquiry-Based Stress Reduction (IBSR): The Work of Byron Katie”—a guided form of self-inquiry which helps to overcome negative thoughts and beliefs—has been shown in an uncontrolled pilot study in Zimbabwe to be helpful.36

Through role-plays and group discussions, our teacher taught their students their experience and the techniques they are using to overcome this major hindrance for a “normal” life. In the course of this project, we and our teachers realized that not only the students learned a lot but also the teachers realized that most of them are facing a lot of internal stigma. Thus, this project taught not only the students but taught also our teachers on how to better cope with the internal and perceived stigma.

The level of understanding stigma and its consequences was heightened to another level when the students wrote scripts concerning stigma and acting themselves. The resulting DVD was distributed throughout Buea, thus making the viewers very aware of the situation the PLWHIV are facing every single day.

In the final phase, a “True/False” knowledge test was repeated with the students from both schools; here, the students from the Test School performed much better than the students from the Control School supporting our concept of stigma reduction. In addition, through casual talk, the students as well as our teachers told us that they have learned so much from this project about themselves and the society and that as a result they have become “different and better” persons. Most of them said that they were discussing the subject of HIV and stigma very intensively with their families and friends, thus disseminating this subject into the community and beyond.

In summary and to put our results in perspective, it has been found that most of the drivers of stigma and discrimination against HIV/AIDS and PLWHIV are community factors. It appears that a combination of successful health education, improvements to health services and now with our project in educating young adults with openly HIV-positive teachers has and will partially tackle HIV-related stigma and help normalize HIV. To go further, there is a great need for political and religious leaders and clinical staff to be supported—financially, legally and normatively—to innovate new ways of generating community discussion and informing policy. Moreover, HIV health care should be delivered through flexible community outreach, and engagement techniques should be developed for those who may avoid such visits for fear of being exposed as HIV-positive to neighbors. To insist that PLWHIV attend clinics to obtain treatment is to fail to acknowledge the importance of stigma in everyday, biographical and epochal time: The consequence can be that PLWHIV wait until they are desperate or die before they get help. Thus, in our setting, in the next phase of our project, we will actively involve political and religious leaders to fight against the HIV/AIDS stigmatization.37

In a recent review article, “Ubuntu” was discussed to alleviate HIV/AIDS stigmatization. It is a spiritual foundation for many African societies, although not all people in Africa are able to connect anything with this term. Essentially, this traditional African aphorism articulates a basic respect and compassion for others. It can be interpreted as both a factual description and a rule of conduct or social ethic. It both describes human beings as being-with-others and prescribes what being-with-others should all be about. While Ubuntu or African Humanism is resiliently religious, Western humanism tends to underestimate or even deny the importance of religious beliefs. Therefore, Ubuntu could be used as a framework in the fight against discrimination and stigmatization aimed at PLWHIV. The Ubuntu values should correlate positively with the HIV/AIDS-related knowledge, attitudes toward persons living with HIV, accurate perceptions regarding HIV/AIDS, and sexual behavior of youths. It is important to note that the Ubuntu concept of dignity and respect for all humans have been used in various interventions to fight HIV/AIDS.37 A classic example of the Ubuntu principle is a collaboration and multi-sectorial approach adopted in Uganda since the early 1990s. Uganda was one of the countries devastated by HIV/AIDS but collective effort demonstrated in political leadership, religious leadership involvement, and community coalitions, greatly fostered efforts to fight the epidemic. These concerted efforts made Uganda AIDS Action, a singular HIV/AIDS action in Africa that has achieved commendation and recommendation around the world. The Ugandan Ministry of Health (2015) attested to this, stating that with strong political leadership, a vibrant civil society, and an open and multi-sectorial approach, Uganda sustained an impressive response to the epidemic. This was built into the Love Life, Stop AIDS control program.38 In Zambia, community leaders such as the clergy strongly advocated for reduced stigma and discrimination against PLWHIV which helped sustained the fight against HIV/AIDS.39 The importance of community leadership’s involvement in eliminating stigma and discrimination against PLWHIV is, therefore, overdue. But, before we have this, we were able to show here that educating the youth through openly HIV-positive teachers seems to be effective.

Of course, we are aware that the reduction of stigma cannot be measured instantly, but we believe strongly that our approach will eventually lead to a reduction in HIV/AIDS stigmatization. For the future, we are planning to repeat the questionnaire with the same and new interviewees and will educate many more students in different schools. And we will involve the political and religious leaders of Buea into this project. To our knowledge, this will be then the first longitudinal study on stigma and also the first study which is using the results from the questionnaire directly to fight stigma by educating secondary schoolchildren.

This pilot project, involving education (through Medical Doctors), openly HIV-positive teachers, and small group work with students, production of a DVD, is the first of its kind. We strongly believe that this work is very important to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma and should also work well in other settings and countries. Limitations to this pilot project are the limited number of students and the interviewed PLWHIV.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, jacobijipactest1addmat for “My Friend with HIV Remains a Friend”: HIV/AIDS Stigma Reduction through Education in Secondary Schools—A Pilot Project in Buea, Cameroon by Christoph Arnim Jacobi, Pascal Nji Atanga, Leonard Kum Bin, Akenji Jean Claude Fru, Gerd Eppel, Victor Njie Mbome, Hannah Etongo Mbua Etonde, Johannes Richard Bogner and Peter Malfertheiner in Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC)

Supplemental Material, jacobijipactest2addmat for “My Friend with HIV Remains a Friend”: HIV/AIDS Stigma Reduction through Education in Secondary Schools—A Pilot Project in Buea, Cameroon by Christoph Arnim Jacobi, Pascal Nji Atanga, Leonard Kum Bin, Akenji Jean Claude Fru, Gerd Eppel, Victor Njie Mbome, Hannah Etongo Mbua Etonde, Johannes Richard Bogner and Peter Malfertheiner in Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC)

Supplemental Material, jacobijipacunaidsquestaddmat for “My Friend with HIV Remains a Friend”: HIV/AIDS Stigma Reduction through Education in Secondary Schools—A Pilot Project in Buea, Cameroon by Christoph Arnim Jacobi, Pascal Nji Atanga, Leonard Kum Bin, Akenji Jean Claude Fru, Gerd Eppel, Victor Njie Mbome, Hannah Etongo Mbua Etonde, Johannes Richard Bogner and Peter Malfertheiner in Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC)

Supplemental Material, jacobijipacunaidsusergaddmat for “My Friend with HIV Remains a Friend”: HIV/AIDS Stigma Reduction through Education in Secondary Schools—A Pilot Project in Buea, Cameroon by Christoph Arnim Jacobi, Pascal Nji Atanga, Leonard Kum Bin, Akenji Jean Claude Fru, Gerd Eppel, Victor Njie Mbome, Hannah Etongo Mbua Etonde, Johannes Richard Bogner and Peter Malfertheiner in Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC)

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Mrs Badini/UNAIDS who kindly provided the UNAIDS “The people living with HIV Stigma Index” to us. We would like to thank our HIV-positive academic trainers/teachers (Delphine Sindoh, Neba Bertha, Che Christopher, Angela Nwa Tangwa, Andreas Efengwa Tongvia, Ayuk Joseph Agbornyong, Sylvester Nzalla Ngomde, Chabiah Michael Foinsangle, Doris Nnam Nyoh, Tal Stephen); without their help this project would not have been possible. In addition, the authors would like to thank the “International Center on the Research on Women (ICRW) who devised the “Tool for action,” which we have used very successfully. The authors equally like to thank the secondary school authorities of the South West Region of Cameroon, who made it possible for us to work with the students. The authors would like to especially thank Merck & Company, United States, and MSD, Germany, who kindly supported the whole project. Without their generous support, the authors would have not been able to successfully complete this project.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The authors recieved financial support from Merck and Company, United States, and MSD, Germany.

ORCID iD: Christoph A. Jacobi, MD, PhD  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1444-517X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1444-517X

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. UNAIDS Fact Sheet, Global statistics-2016. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Englewood Hills, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Holzemer WL, Uys L, Makoae L, et al. A conceptual model of HIV/AIDS stigma from five African countries. JAN. 2007;58(6):541–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nyblade LC. Measuring HIV Stigma: existing knowledge and gaps. Psychol, Health Med. 2006;11(3):335–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Aids Epidemic Update. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization (WHO)/Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Treating 3 Million by 2005: Making It Happen—The WHO strategy. The WHO and UNAIDS Global Initiative to Provide Antiretroviral Therapy to 3 Million People With HIV/AIDS in Developing Countries by the end of 2005. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (WHO)/Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). [Google Scholar]

- 7. UN General Assembly. Political declaration on HIV and AIDS: on the fast-track to accelerate the fight against HIV and to end the AIDS epidemic by 2030, resolution adopted by the general assembly, 8 June 2016.

- 8. Chan BT, Tsai AC, Siedner MJ. HIV treatment scale-up and HIV-related stigma in sub-Saharan Africa: a longitudinal cross-country analysis. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(8):1581–1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chan BT, Tsai AC. HIV stigma trends in the general population during antiretroviral treatment expansion: analysis of 31 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, 2003–2013. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(5):558–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24(6):518–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mak WW, Poon CY, Pun LY, Cheung SF. Meta-analysis of stigma and mental health. Soc Sci Med. 2007; 65(2):245–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Herek GM, Capitanio JP, Widaman KF. Stigma, social risk, and health policy: public attitudes toward HIV surveillance policies and the social construction of illness. Health Psychol. 2003; 22(5):533–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nyblade L, Pande R, Mathur S, et al. Disentangling HIV and AIDS Stigma in Ethopia, Tanzania and Zambia. Washington, DC: International Center for Research on Women; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee RS, Kochman A, Sikkema KJ. Internalized stigma among people living with HIV-AIDS. AIDS and behaviour. 2002;6:309–319. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ahmeda S, Autreya J, Katz IT, et al. Why do people living with HIV not initiate treatment? A systematic review of qualitative evidence from low- and middle-income countries. Soc Sci Med. 2018;213:72–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sengupta S, Banks B, Jonas D, Miles MS, Smith GC. HIV interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(6):1075–1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stangl AL, Lloyd JK, Brady LM, Holland CE, Baral S. A systematic review of interventions to reduce HIV-related stigma and discrimination from 2002 to 2013: how far have we come? J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(3 Suppl 2):18734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mak WWS, Mo PKH, Ma GYK, et al. Meta-analysis and systematic review of studies on the effectiveness of HIV stigma reduction programs. Soc Sci Med. 2017;188:30–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. The People Living with HIV Stigma Index. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jacobi CA, Atanga PN, Bin LK, et al. HIV/AIDS-related stigma felt by people living with HIV from Buea, Cameroon. AIDS Care. 2013;25(2):173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. International Centre for the Research on Women. Understanding and Challenging HIV Stigma: A Toolkit for Action. Washington DC, USA: ICRW; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pleck JH, O’Donnell L, O’Donnell C, Snarey J. AIDS-phobia, contact with AIDS, and AIDS-related job stress in hospital workers. J Homosex. 1988;15(3-4):41–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: a conceptual framework and implications for action. Soc Sci Med. 2003; 57(1):13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), Ghana Health Services (GHS) and ORC Macro. 2008 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey. Calverton: GSS, GHS, and ORC Macro; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bos AER, Schaalma HP, Pryor B. Reducing AIDS-related stigma in developing countries: the importance of theory- and evidence-based interventions. Psychol, Health Med. 2008;13(4):450–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brown L, Macintyre K, Trujillo L. Interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS Stigma: what have we learned? AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15(1):49–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Heijnders M, van der Meij S. The fight against stigma: an overview of stigma-reduction strategies and intervention. Psychol, Health Med. 2006;11(3):353–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mak WW, Cheng SS, Law RW, Cheng WW, Chan F. Reducing HIV-related stigma among health-care professionals: a game-based experiential approach. AIDS Care. 2015;27(7):855–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ishikawa N, Pridmore P, Carr-Hill R, Chaimuangdee K. The attitudes of primary schoolchildren in Northern Thailand towards their peers who are affected by HIV and AIDS. AIDS Care. 2011;23(2):237–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. MSF. Waiting Isn’t An Option: Preventing and Surviving Advanced HIV. MSF Briefing Paper Geneva, Switzerland; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Decroo T, Telfer B, Biot M, et al. Distribution of antiretroviral treatment through self-forming groups of patients in Tete Province, Mozambique. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56(2):e39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wilkinson LS. ART adherence clubs: a long-term retention strategy for clinically stable patients receiving antiretroviral therapy. S Afr J HIV Med. 2013; 14(2):48–57. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Luque-Fernandez MA, Van Cutsem G, Goemaere E, et al. Effectiveness of patient adherence groups as a model of care for stable patients on antiretroviral therapy in Khayelitsha, Cape Town, South Africa. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Abaynew Y, Deribew A, Deribe K. Factors associated with late presentation to HIV/AIDS care in South Wollo ZoneEthiopia: a case-control study. AIDS Res Ther. 2011;8:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Aniley AB, Ayele TA, Zeleke EG, et al. Factors associated with late Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) diagnosis among peoples living with it, Northwest Ethiopia: hospital based unmatched case-control study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. France NF, MacdonaldI SHF, Conroy RR, et al. We are the change – An innovative community-based response to address self-stigma: A pilot study focusing on people living with HIV in Zimbabwe. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0210152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tarkang EE, Pencille LB, Komesour J. The Ubuntu concept, sexual behaviors and stigmatization of persons living with HIV in Africa: a review article. J Public Health Africa. 2018;9(2):677: 96–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ugandan Ministry of Health. AIDS control programme; 2015. http://www.health.go.ug/programs/aids-control-program. Accessed August 2019.

- 39. Paterson AS. Church mobilisation and HIV/AIDS treatment in Ghana and Zambia: a comparative analysis. Afr J AIDS Res. 2010;9(4):407–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, jacobijipactest1addmat for “My Friend with HIV Remains a Friend”: HIV/AIDS Stigma Reduction through Education in Secondary Schools—A Pilot Project in Buea, Cameroon by Christoph Arnim Jacobi, Pascal Nji Atanga, Leonard Kum Bin, Akenji Jean Claude Fru, Gerd Eppel, Victor Njie Mbome, Hannah Etongo Mbua Etonde, Johannes Richard Bogner and Peter Malfertheiner in Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC)

Supplemental Material, jacobijipactest2addmat for “My Friend with HIV Remains a Friend”: HIV/AIDS Stigma Reduction through Education in Secondary Schools—A Pilot Project in Buea, Cameroon by Christoph Arnim Jacobi, Pascal Nji Atanga, Leonard Kum Bin, Akenji Jean Claude Fru, Gerd Eppel, Victor Njie Mbome, Hannah Etongo Mbua Etonde, Johannes Richard Bogner and Peter Malfertheiner in Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC)

Supplemental Material, jacobijipacunaidsquestaddmat for “My Friend with HIV Remains a Friend”: HIV/AIDS Stigma Reduction through Education in Secondary Schools—A Pilot Project in Buea, Cameroon by Christoph Arnim Jacobi, Pascal Nji Atanga, Leonard Kum Bin, Akenji Jean Claude Fru, Gerd Eppel, Victor Njie Mbome, Hannah Etongo Mbua Etonde, Johannes Richard Bogner and Peter Malfertheiner in Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC)

Supplemental Material, jacobijipacunaidsusergaddmat for “My Friend with HIV Remains a Friend”: HIV/AIDS Stigma Reduction through Education in Secondary Schools—A Pilot Project in Buea, Cameroon by Christoph Arnim Jacobi, Pascal Nji Atanga, Leonard Kum Bin, Akenji Jean Claude Fru, Gerd Eppel, Victor Njie Mbome, Hannah Etongo Mbua Etonde, Johannes Richard Bogner and Peter Malfertheiner in Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC)