Abstract

Introduction

Improper positioning, attachment, and suckling are constructs for ineffective breastfeeding technique (IBT). IBT results in inadequate intake of breast milk, which leads to poor weight gain, stunting, and declines immunity. Besides, IBT increases the risk of postpartum breast problems. Despite its impact on maternal and child health, breastfeeding technique is not well studied in Ethiopia. Hence, the purpose of this study was to assess the prevalence of IBT and associated factors among lactating mothers attending public health facilities of South Ari district, Southern Ethiopia.

Materials and methods

An institution-based cross-sectional study was conducted among 415 lactating mothers attending public health facilities of South Ari district from March 1-29, 2019. A structured observational checklist and interviewer-administered questionnaires were used. Bivariable and multivariable analyses were carried out using binary logistic regression to assess the association between explanatory variables and IBT. Statistical significance was declared at p-value < 0.05.

Results

Overall, the prevalence of IBT was 63.5% [95% confidence interval (CI); 59.0%, 68.0%]. Having no formal education [adjusted odds ratio (AOR): 5.0, 95% CI: 2.3, 10.5], delivering at home [AOR: 4.5; 95% CI; 1.6, 13.1], having breast problems [AOR: 2.5, 95% CI: 1.1, 5.7], being primiparous [AOR: 1.8, 95% CI: 1.0, 3.2], not receiving counseling during pregnancy and postnatal period [AOR: 2.3, 95% CI: 1.4, 3.9 and AOR: 2.5, 95% CI: 1.3, 5.1 respectively] were significantly associated with IBT.

Conclusion

IBT was very high in the study area. Thus, empowering women, increasing institutional delivery, and providing continuous counseling about breastfeeding throughout the maternal continuum of care is invaluable to improve breastfeeding techniques.

Introduction

Breast milk provides the ideal nutrition for infants; nearly a perfect mix of vitamin, protein, fat, and antibodies [1–3]. Breastfeeding is imperative for the mother to facilitate involution [4], reduce the risk of breast cancer [5], epithelial ovarian cancer [6], osteoporosis [7], and coronary artery disease [8]. Ensuring universal breastfeeding can avert 823,000 under-five children deaths and 20,000 breast cancer deaths every year [9]. However, most mothers do not realize breastfeeding technique as a learned skill that needs practice and patience [10].

Breastfeeding technique is the composite of positioning, attachment, and suckling. Positioning denotes the technique in which the infant is held in relation to the mother's body. Attachment indicates whether the infant has enough areola and breast tissue in the mouth, and suckling denotes to the drawing of milk into the mouth from the nipple [11]. Improper positioning, attachment, and suckling are constructs for ineffective breastfeeding technique (IBT), which results in inadequate intake of breast milk that leads to poor weight gain, stunting, and declines immunity [10, 12]. The 2019 mini-Ethiopian demographic health survey (MEDHS) reported that 37%, 21% and 7% of under-five children are stunted, underweight and wasted respectively [13]. IBT is also the leading cause of breast engorgement, cracked nipple, mastitis, and breast abscess [14, 15].

Although there is a significant reduction in the global child mortality over the past three decades, around 5.3 million under-five children died in 2018; sub-Saharan Africa contributes ~50% of these deaths [16]. Suboptimal breastfeeding practices increase the risk of infant mortality; non-breastfed and partially breastfed infants are 14 and 3 times higher risk of death in the first six months as compared to exclusively breastfed infants [17]. Moreover, poor positioning increases sufferings from diarrheal and respiratory infections [18]. IBT results in a reduction of exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) practice [11]. Even though there are improvements over the past fourteen years, in Ethiopia only 59.0% of infants under 6 months are engaged in EBF [13].

The prevalence of IBT ranges from 30-70% in Denmark, Brazil, Nepal, India, Libya, and Ethiopia [15, 19–23]. Breast problems, low level of maternal education, lack of breastfeeding experience, home delivery, insufficient counseling, operative deliveries, and primiparity are some of the factors that contribute to IBT [11, 15, 21].

Despite effective breastfeeding techniques have a proven short and long term benefit both for the mother and her child, its practice is not satisfactory in developing countries [24]. Studies that have assessed factors associated with IBT have been mainly conducted in middle and high-income countries [15, 19, 20, 22, 23]. Additionally, such studies have been conducted immediately after birth before the mother is stable and comfortable which may ultimately influence breastfeeding techniques. As such, there is a paucity of data on IBT and its associated factors in developing countries. Furthermore, considering the time of observing breastfeeding techniques, especially not immediately after birth, would ensure that breastfeeding techniques are observed while mothers are stable and comfortable. Besides, there is a dearth of evidence concerning IBT in southern Ethiopia. Hence, this study was initiated to determine the prevalence of IBT and associated factors in South Ari district, Southern Ethiopia.

Materials and methods

Study area, design and period

An institution-based cross-sectional study was conducted from March 1-29, 2019 at public health facilities of the South Ari district. South Ari district is one of the districts in the south Omo zone and it is located 17 km away from Jinka (i.e. the capital of the zone) and 771 Km away from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. The population of the district is around 254,000; of this, 8,788 were reproductive-age women. The district had one district hospital and eight public health centers that provide delivery, postnatal and immunization services for the catchment area population.

Study population

All mothers who visited public health facilities of South Ari district for immunization and/or postnatal care services were considered as the study population. Lactating mothers who had under six-month infants were included. Those mothers who were seriously ill and unable to breastfeed their newborn, whose infants were critically ill and neonates with major congenital cleft lip and cleft palate were excluded from the study.

Sample size determination

The sample size was calculated by EpiInfo-7 StatCalc using a single population proportion formula using the following assumptions: 57.0% (prevalence of IBT from a study conducted in Harar, Ethiopia [21], 95% level of confidence, and 5% margin of error. By adding a none response rate of 10% the final sample size was 415.

Sampling technique

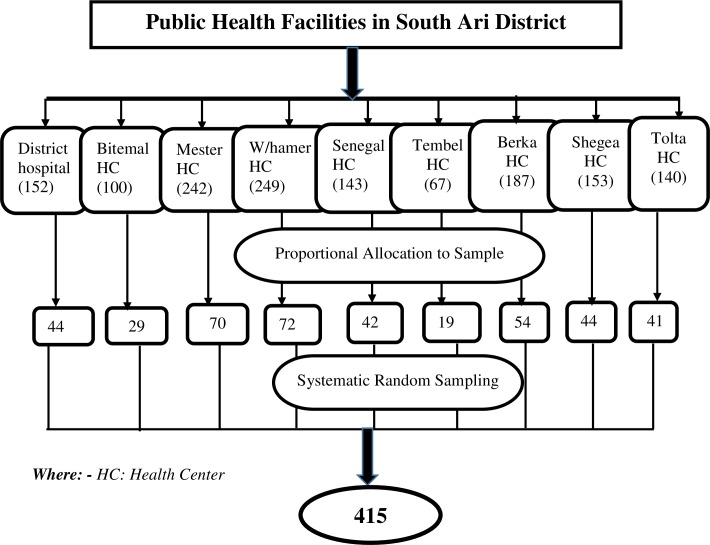

All public health facilities in South Ari district (one district hospitals and eight health centers) were included in this study and the sample size was allocated proportionally to each health facility based on the number of postnatal care (PNC) and immunization service attendants in the last quarter of 2018. Based on the review, the total number of lactating mothers who came for immunization and PNC services were 1433. Then, to get the sampling interval total number of lactating mothers who came for immunization and PNC in the last quarter of 2018 was divided by the number of the required sample size, which is 1433/415=3. Finally, the data were collected by using a systematic random sampling technique with an interval of three (k =3) (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Schematic presentation of the sampling procedure for the study conducted among lactating mothers attending public health facilities of South Ari district, Southern Ethiopia, 2019.

Data collection tool

A structured observational checklist and interviewer-administered questionnaire were prearranged after reviewing previous literature [15, 21]. The tool comprises socio-demographic, maternal and infant characteristics. The WHO B-R-E-A-S-T-Feed observational checklist was used to assess mother and baby’s position, infant’s mouth attachment, and suckling. According to WHO criteria, four components (i.e. baby body should be straight and slightly extended, baby body close and turned toward the mother, the whole body supported, and baby facing toward the mother’s breast) are used to assess the baby’s position in relation to the mother’s body. Likewise, attachment of the baby to the breast was assessed by four components: more areola is visible above the baby’s upper lip, the baby’s mouth is wide open, the baby’s lower lip is turned outward and the baby’s chin is touching or almost touching the breast. Furthermore, suckling was assessed by three components: slow sucks, deep suckling and sometimes pausing [25, 26].

Data collection procedure

Eight diploma midwives and three bachelors of science midwives were recruited as data collectors and supervisors, respectively. A 2-days training about the purpose of the study and process of data collection was given to the data collection team. The positions of the mother and baby, infant’s mouth attachment to breast and suckling were observed through hands-on practice. Data collectors observe the breastfeeding process for five minutes and record as per the WHO B-R-E-A-S-T feed observation form. The observation was done by asking the mother to put her infant to the breast. When the infant was fed in the previous hour, the mother was kindly asked to stay away for a few minutes and observation of the breastfeeding technique was done during the next time when the baby was ready to feed. Data collection, supervision was carried out on a daily basis throughout the study period.

Study variables and measurements

Ineffective breastfeeding technique, obtained from three composite variables (i.e. Positioning, attachment, and suckling), was the outcome variable (Table 1). Furthermore, socio-demographic, maternal and infant characteristics were the independent variables for this study. Maternal age, in completed years, was categorized and coded into four groups as ‘< 20 years’= “1”, ‘20-25 years’= “2”, ‘26 -30 years’ = “3” and ‘> 30 years’= “4”. Maternal level of education was categorized and coded into three as ‘no formal education’ = “1”, ‘attend primary education (grade 1-8)’= “2”, and ‘secondary education and above (grade nine and above)’ = “3”. Parity, the total number of live births after the age of viability (28 completed weeks of gestation), was categorized and coded as ‘primipara’ = “1” and ‘multipara’ = “2”. Antenatal care (ANC) was categorized and coded into two as ‘Yes’ = “1” and ‘No’ = “2”.

Table 1. Description of variables and measurements for the study in South Ari District, Southern Ethiopia, 2019.

| Variables | Descriptions | Measurement/Category |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent/outcome Variable | ||

| Ineffective breastfeeding (IBT) | IBT was a composite variable of the three constructs (positioning, attachment, and suckling) such that lactating women with at least one of the constructs categorized as “poor” were regarded as having IBT [21]. | Those mothers with IBT were categorized as ‘Yes’ and labeled as “1” and mothers with effective breastfeeding techniques were categorized as ‘No’ and labeled as “0”. |

| Composite Variables | ||

| Positioning | The technique in which the infant is held in relation to the mother's body. Good positioning: when at least three out of four criteria for infant positioning was fulfilled; average positioning: when any two of the four criteria were correct and poor positioning when only one or none criterion has been fulfilled [25, 27]. | In the beginning, it was categorized as good, average and poor positioning. Then, to create a dummy variable good and average positioning were merged as ‘good’ and labeled as “0” and ‘poor positioning” was coded as it is and labeled as “1”. |

| Attachment | It indicates whether the infant has enough areola and breast tissue in the mouth. Good attachment: when at least three out of four criterions have been fulfilled. Average attachment: when any two of the four criterions have been fulfilled. Poor attachment: when only one or none out of four criterions have been fulfilled [21, 27]. | Like that of positioning, first, it was categorized as a good, average and poor attachment. Then, to create a dummy variable good and average attachment were merged as ‘good attachment’ and labeled as “0” and ‘poor attachment” was coded as it is and labeled as “1”. |

| Suckling | Drawing of milk into the mouth from the nipple. Effective suckling: at least two out of three criterions have been fulfilled. Ineffective suckling: only one or none from three criterions has been fulfilled [25, 27]. | Suckling was coded as ‘effective suckling’, labeled as “0” and ‘ineffective suckling’, labeled as “1”. |

Prenatal counseling, counseling rendered to pregnant women about birth preparedness and complication readiness, breastfeeding and other postpartum related complications, was categorized into two as those mothers who received counseling were categorized and coded as ‘Yes’= “1” and those who didn’t receive were categorized and coded as ‘No’ = “2”. Likewise, Postnatal counseling, service designed immediately after delivery to provide emotional support for mothers and their partners about breastfeeding, postpartum related complications, and safe motherhood, was categorized into two; those who received counseling were coded as ‘Yes’= “1” and those who didn’t receive were coded as ‘No’ = “2”. Place of delivery, the place where an infant was born, was categorized and coded into three as ‘hospital’ =”1”, ‘health center’ = “2” and ‘home’ = “3”. Breast problems such as breast engorgement, mastitis, and/or breast abscess experienced by women during the postpartum period. It was categorized into two as those who faced any type of breast problems were categorized and coded as ‘Yes’ = “1” and those who didn’t encounter it was categorized and coded as ‘No’ = “2”. Residence, the place where the respondent lives, categorized and coded into two as urban = “1” and rural = “2”. Occupation, the current employment status and specific career of the participant, was categorized and coded into two as housewives = “1” and other = “2”. Other includes government employees, NGO workers, daily laborers, and self-employees. Birth weight, bodyweight of a baby at its birth, was categorized and coded into three as low birth weight (<2500 gram) = “1”, normal (2500-3999 gram) = “2”, and macrosomia (>4000 gram) = “3”. Mode of delivery, childbirth delivery options that natural unassisted childbirth, vaginal operative deliveries and delivery by cesarean section, was categorized into two as normal = “1”, and cesarean section = “2”.

Data quality control

Rigorous training about the objectives of the study and the procedure to be followed during data collection was given for the data collectors. Structured and validated checklists were adopted from the WHO B-R-E-A-S-T feed observation form [28] and translated into local languages (i.e. Arigna and Amharic). The tool was pre-tested among 21 mothers from the kako health center. Close supervision was undertaken on a daily basis throughout the study period. Double data entry was done on 5% of the sample by two data clerks and consistency of the entered data were cross-checked by comparing the two separately entered data sets.

Data management and analysis

The data were visually checked by the investigators and entered to EpiData statistical software version 3.1. Then, the data were exported to SPSS version 25.0 for cleaning and analysis. Descriptive summary measures such as frequency, percentages, mean and standard deviation were used to describe characteristics of the participants. Binary logistic regression was carried out to identify the factors associated with IBT. To control possible confounding factors, variables with a p-value of ≤0.25 in the bivariate analysis were taken to the multivariable analysis. Multicollinearity and model fitness was checked using standard error and Hosmer-Lemeshow test respectively. The adjusted odds ratio (AOR), with 95% confidence intervals (CI), was used to identify the independent variables associated with IBT. All tests were two-sided and statistical significance was declared at P-value < 0.05.

Ethical consideration

Ethical approval was obtained from Arba Minch University, College of medicine and health sciences, Institutional Ethical Review Board (IRB). Permission was secured from the hospital and health center administrators. Moreover, voluntary informed verbal consent was obtained from the study participants before the initiation of the data collection. Code numbers were used throughout the study to maintain the confidentiality of information gathered from each study participant.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

A total of 414 participants were involved, making a response rate of 99.8%. The mean (± standard deviation (SD)) age of the participants was 26.5 (±5.2 SD) years. Of the participants, 31.9% were within the age group of 26-30 years, and 66.9% were protestant by religion. The majority of the participants, 86.3% were married, 69.1% were housewives, 63.3% were rural dwellers, and 60.8% didn’t attend formal education (Table 2).

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics of participants attending public health facilities of South Ari district, Southern Ethiopia, 2019 (n= 414).

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| < 20 | 72 | 17.4 |

| 20–25 | 124 | 30.0 |

| 26–30 | 132 | 31.9 |

| > 30 | 86 | 20.7 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Ari | 319 | 77.1 |

| Amhara | 52 | 12.6 |

| Wolayita | 31 | 7.5 |

| Othera | 12 | 2.8 |

| Religion | ||

| Protestant | 277 | 66.9 |

| Orthodox | 96 | 23.2 |

| Muslim | 25 | 6.0 |

| Otherb | 16 | 3.9 |

| Level of education | ||

| No formal education | 252 | 60.8 |

| Primary school | 100 | 24.2 |

| Secondary school and above | 62 | 15.0 |

| Occupation | ||

| Housewife | 286 | 69.1 |

| Government employee | 38 | 9.2 |

| Self-employed | 42 | 10.1 |

| Daily laborer | 33 | 8.0 |

| Otherc | 15 | 3.6 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 357 | 86.3 |

| Single | 20 | 4.8 |

| Divorced | 24 | 5.8 |

| Otherd | 13 | 3.1 |

| Residence | ||

| Rural | 304 | 73.4 |

| Urban | 110 | 26.6 |

| Family size | ||

| < 5 | 300 | 72.5 |

| ≥ 5 | 114 | 27.5 |

aOromo, konso and Gamo Gofa

bCatholic, yewuha miskir

cNGO, student, farmer

dWidowed, Separated

Obstetric characteristics

Among the participants, 33.1% were primipara, 95.6% had ANC follow-up, and 93.2% were delivered through the natural route. Four-fifths (80.2%) of the participants received counseling about breastfeeding techniques after delivery. The majority (86.7%) of the participants were delivered at term. The birth weight of the newborns was within the normal range for 92.0% of the participants. Nearly half (46.1%) of the infants were male (Table 3).

Table 3. Obstetric characteristics of participants attending public health facilities of South Ari district, southern Ethiopia, 2019 (n = 414).

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parity | Primipara | 137 | 33.1 |

| Multipara | 277 | 66.9 | |

| Ever had stillbirth | Yes | 97 | 23.4 |

| Ever had a neonatal death | Yes | 51 | 12.3 |

| Antenatal care | Yes | 396 | 95.6 |

| Pregnancy status | Planned | 323 | 78.0 |

| Unplanned | 91 | 22.0 | |

| Received counseling during pregnancy | Yes | 245 | 59.2 |

| Place of delivery | Hospital | 123 | 29.7 |

| Health center | 236 | 57.0 | |

| Home | 55 | 13.3 | |

| Mode of delivery | Normal delivery | 383 | 92.5 |

| Cesarean section | 31 | 7.5 | |

| Received postnatal counseling about BFT* | Yes | 332 | 80.2 |

| Gestational age at delivery | Term | 359 | 86.7 |

| Preterm | 34 | 8.2 | |

| Post-term | 21 | 5.1 | |

| Birth weight | Low birth weight | 15 | 3.7 |

| Normal | 381 | 92.0 | |

| Macrosomia | 18 | 4.3 | |

| Age of the infant | < 42 days | 164 | 39.6 |

| ≥ 42 days | 250 | 60.4 | |

| Sex of the Infant | Male | 191 | 46.1 |

| Female | 223 | 53.9 | |

| Breast problem | Yes | 59 | 14.3 |

| Giving pre-lacteal feeding | Yes | 26 | 6.3 |

| Initiate complementary feeding | Yes | 137 | 33.1 |

*Breastfeeding techniques

Status of ineffective breastfeeding technique

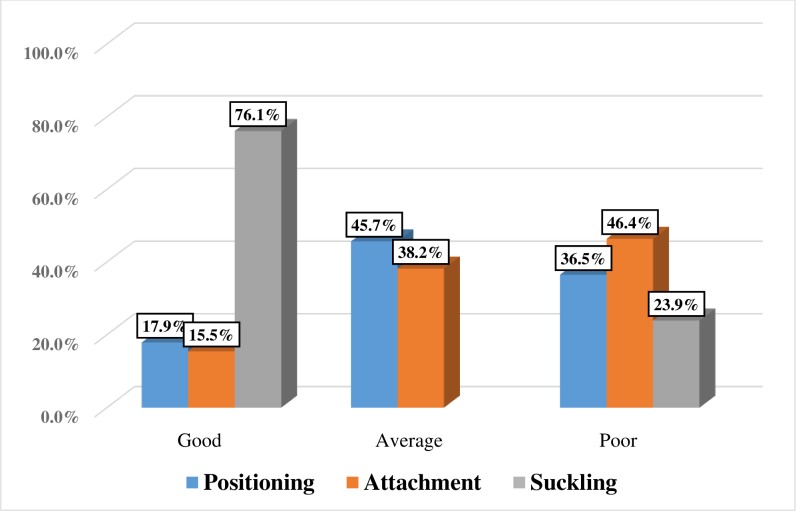

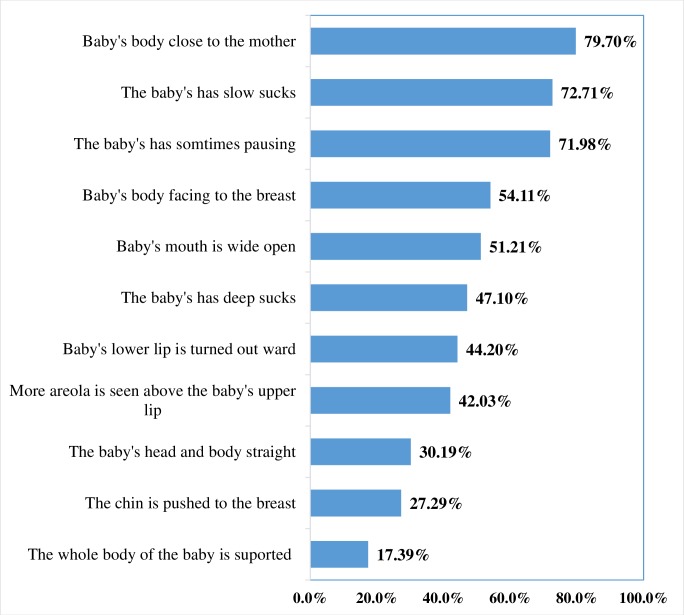

Overall, the prevalence of IBT was 63.5% (95%, CI: 59.0%, 68.0%). Poor positioning was observed among 36.4% of women (Fig 2). Only 17.4% of the participants supported the whole body of their baby and the baby’s head and body were straight for 30.2% of the newborns (Fig 3).

Fig 2. Status of breastfeeding technique constructs in public health facilities of South Ari district, Southern Ethiopia, 2019 (n=414).

Fig 3. Effective breastfeeding practice for each item in public health facilities of South Ari district, Southern Ethiopia, 2019 (n=414).

Factors associated with ineffective breastfeeding technique

The odds of IBT was 5 times (AOR=5.0; 95% CI: 2.3, 10.5) higher among mothers who did not attend formal education as compared to those who had secondary and above education. IBT was 4.5 times (AOR=4.5; 95% CI; 1.6, 13.1) higher among mothers who delivered at home as compared to mothers who delivered in the hospital. Likewise, as compared to multiparous, the odds of IBT was almost two times (AOR=1.8; 95% CI: 1.0, 3.2) higher among primiparous women. Mothers who had breast problems were 2.5 times (AOR=2.5; 95% CI: 1.1, 5.7) more likely to exhibit IBT as compared to their counterparts. Moreover, the odds of IBT was 2.3 times (AOR=2.3; 95% CI: 1.4, 3.9) and 2.5 times (AOR=2.5; 95% CI: 1.3, 5.1) higher among participants who did not received counseling about breastfeeding techniques during pregnancy and at the postnatal period respectively as compared to their counterparts (Table 4).

Table 4. Factors associated with ineffective breastfeeding technique in public health facilities of South Ari district, Southern Ethiopia, 2019 (n = 414).

| Variables | aIBT | bCOR (95% CI) | P-value | cAOR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N, %) | No (N, %) | |||||

| Age category in completed years | ||||||

| <20 | 53 (73.6) | 19 (26.4) | 1.6 (0.8, 3.1) | 0.195 | 1.1 (0.4, 2.7) | |

| 20-25 | 77 (62.0) | 47 (38) | 0.9 (0.5, 1.6) | 0.784 | 0.9 (0.4, 1.8) | |

| 26 -30 | 78 (59) | 54 (41) | 0.8 (0.5, 1.4) | 0.472 | 0.8 (0.4, 1.6) | |

| >30 years | 55 (64) | 31 (36) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Educational status | ||||||

| No formal education | 178 (70.6) | 74 (29.4) | 4.7 (2.6, 8.4) | 0.0001 | 5.0 (2.3, 10.5)* | |

| Primary school | 64 (64) | 36 (36) | 3.4 (1.8, 6.7) | 0.0001 | 3.3 (1.4, 7.6)* | |

| Secondary & above | 21 (33.8) | 41 (66.2) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Parity | ||||||

| Primipara | 96 (70.1) | 41 (29) | 1.5 (0.99, 2.4) | 0.052 | 1.8 (1.0, 3.2)* | |

| Multipara | 167 (60.3) | 110 (39.7) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Antenatal care visit | ||||||

| Yes | 248 (62.6) | 148 (37.4) | 1.0 |

0.088 |

1.0 | |

| No | 15 (83.3) | 3 (16.7) | 2.9 (0.85, 10.4) | 2.3 (0.5, 10.6) | ||

| Prenatal counseling about breastfeeding techniques | ||||||

| Yes | 134 (54.7) | 111 (45.3) | 1.0 |

0.0001 |

1.0 | |

| No | 129 (76.3) | 40 (23.7) | 2.7(1.7, 4.1) | 2.3 (1.4, 3.9)* | ||

| Place of delivery | ||||||

| Hospital | 66 (53.6) | 57 (46.4) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Health center | 147 (62.3) | 89 (37.7) | 1.76 (1.14, 2.7) | 0.115 | 1.01 (0.6, 1.7) | |

| Home | 50 (90.9) | 5 (9.1) | 12.4 (2.8, 54.6) | 0.0001 | 4.5 (1.6, 13.1)* | |

| Postnatal care counseling about breastfeeding | ||||||

| Yes | 195 (58.7) | 137 (41.3) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| No | 68 (82.9) | 14 (17.1) | 3.4 (1.8, 6.3) | 0.0001 | 2.5 (1.3, 5.1)* | |

| Breast problem | ||||||

| No | 213 (60) | 142 (40) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Yes | 50 (84.7) | 9 (15.3) | 3.7(1.8, 7.8) | 0.001 | 2.5 (1.1, 5.7)* | |

| Residence | ||||||

| Rural | 203 (66.8) | 101 (33.2) | 1.7 (1.1, 2.6) | 0.023 | 1.7 (0.9, 2.9) | |

| Urban | 60 (54.5) | 50 (45.5) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Occupation | ||||||

| House wife | 194 (67.8) | 92 (32.2) | 1.8 (1.2, 2.8) | 0.007 | 1.3 (0.7, 2.3) | |

| Otherd | 69 (54) | 59 (46) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Birth weight | ||||||

| Low birth weight | 11 (73.3) | 4 (26.7) | 5.5 (1.2, 24.8) | 0.027 | 2.5 (0.5, 13.2) | |

| Normal | 246 (64.6) | 135 (35.4) | 3.6 (1.3, 9.9) | 0.11 | 2.5 (0.9, 7.3) | |

| Macrosomia | 6 (33.3) | 12(66.7) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Mode of delivery | ||||||

| Normal | 247 (64.5) | 136 (45.5) | 1.7(0.8, 3.6) | 0.156 | 1.3 (0.5, 3.0) | |

| Cesarean delivery | 16 (51.6) | 15 (48.4) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

* Significant at p < 0.05

aIneffective breastfeeding

bcrude odds ratio

cadjusted odds ratio

dgovernment employee, daily laborer, NGO worker, self-employee

Discussion

This study revealed that 63.5% of lactating women exhibit IBT. Having no formal education, delivering at home, having breast problems, being primiparous, not receiving counseling during pregnancy and in the postnatal period were significantly associated with IBT.

The prevalence of IBT in this study is higher than the studies conducted in the rural population of India (49%) [22], Cheluvamba hospital, India (57%) [29], Libya (52%) [15] and Harar, Ethiopia (57%) [21]. On the contrary, it is lower than a study conducted in West Bengal/Kolkata hospital India (69.7%) [19]. This discrepancy might be due to the difference in the quality of health services, counseling, and demonstration about breastfeeding techniques during pregnancy and the postpartum period. In addition, it might be due to socio-cultural, study settings and period variation.

The odds of IBT was five times higher among women having no formal education as compared to those who attend secondary and above education. This finding is in line with the studies conducted in Indian East Delhi, West Bengal Kolkata hospital, Saudi Heraa general hospital, Bhaktapur district of Nepal, Sri Lanka and Harare Ethiopia [10, 19, 21, 29–31]. This might be probably due to the fact that uneducated women need much more time to adhere and implement effective breastfeeding techniques. In addition, unschooled mothers may face some difficulties to acquire and observe health information about appropriate breastfeeding practice.

In this study, the likelihood of having IBT was almost two times higher among the primiparous as compared to multiparous mothers. This is in line with the studies conducted in India, Denmark, Cheluvamba Hospital of India, Libya, Harar Ethiopia and Areka town Ethiopia [10, 15, 21, 27, 29]. This might be due to a shortage of information, skill, and experience about breastfeeding techniques. Moreover, multiparous women are more likely to have gained child-rearing experience (including feeding techniques) from their previous pregnancies.

The odds of IBT was three times higher among participants with breast problems as compared to their complements. This is in line with studies conducted in Libya, and Ethiopia [15, 21]. This might be due to the fact that mothers with breast problems may have severe pain that hinders them to apply breastfeeding techniques. In addition, it is difficult to correctly attach the infant’s mouth with engorged and cracked nipples due to distension and edema of the nipple.

Those mothers who did not receive counseling about breastfeeding techniques after delivery were almost three times more likely to exhibit IBT as compared to those who received adequate information. This is consistent with the studies conducted in rural areas of rural areas of Nagpur district, India and Harar Ethiopia [20, 21]. Likewise, the odds of IBT was two times higher among participants who didn’t receive counseling about breastfeeding techniques during pregnancy as compared to their counterparts. This finding is consistent with the studies conducted in Libya and Coastal Karnataka [15, 32]. This might be due to the fact that adequate counseling about breastfeeding during pregnancy and the postpartum period are imperative to achieving effective breastfeeding techniques. Moreover, psychological support given for lactating mothers has a significant effect on breastfeeding technique enhancement [29].

The odds of IBT was five times higher among participants who delivered at home as compared to those who delivered in the hospital. This is in line with the studies conducted in the Bhaktapur district of Nepal and Harar, Ethiopia. [21, 31]. The possible reason is that women who delivered in the hospital are likely to receive continuous psychological and hands-on support to realize effective breastfeeding techniques.

Generally, this study reported the magnitude of IBT using a standardized observational checklist and interviewer-administered questionnaires. Though it is very minimal, observer bias and hawthorn effect might be introduced. To minimize observer bias and hawthorn effect, the data collectors were well trained and qualified, and each study participant was observed in a private setting respectively. Due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, the design could not allow causality to be inferred. Since the study was restricted to public health facilities, it was difficult to generalize to all lactating mothers living in the district. Thus, to minimize the effect of the aforementioned limitations scholars with similar interest are recommended to conduct a community-based study that addresses cultural practices that hinders effective breastfeeding techniques. Overall, the findings from this study are fundamental for policy-makers to design appropriate intervention strategies to improve breastfeeding techniques.

Conclusions

In the study area, the proportion of IBT was very high. Having no formal education, delivering at home, having breast problems, being primiparous, not receiving counseling during pregnancy and in the postnatal period were significantly associated with IBT. Hence, much work is needed to improve breastfeeding techniques among lactating. Empowering women, increasing institutional delivery, and providing continuous support about appropriate breastfeeding techniques throughout the maternal continuum care is mandatory to come up with a significant reduction in IBT.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(SAV)

Acknowledgments

We want to extend our appreciation to Arba Minch University, study participants, data collectors, supervisors, and south ari district health facilities staff for their invaluable support to make this study real.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Wambach K, Spencer B. Breastfeeding and human lactation: Jones & Bartlett Publishers; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yasmeen T, Kumar S, Sinha S, Haque MA, Singh V, Sinha S. Benefits of breastfeeding for early growth and long term obesity: A summarized review. International Journal of Medical Science and Diagnosis Research (IJMSDR). 2019;3(1). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westerfield KL, Koenig K, Oh R. Breastfeeding: Common Questions and Answers. American family physician. 2018;98(6). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.As' ad S, Idris I. Relationship between Early Breastfeeding Initiation and Involution Uteri of Childbirth Mothers in Nenemallomo Regional Public Hospital and Arifin Nu'mang Public Regional Hospital of Sidenreng Rappang Regency in 2014. Indian Journal of Public Health Research & Development. 2019;10(4):838–44. [Google Scholar]

- 5.González-Jiménez E. Breastfeeding and Reduced Risk of Breast Cancer in Women: A Review of Scientific Evidence. Selected Topics in Breastfeeding: IntechOpen; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Modugno F, Goughnour SL, Wallack D, Edwards RP, Odunsi K, Kelley JL, et al. Breastfeeding factors and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecologic oncology. 2019;153(1):116–22. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duan X, Wang J, Jiang X. A meta-analysis of breastfeeding and osteoporotic fracture risk in the females. Osteoporosis International. 2017;28(2):495–503. 10.1007/s00198-016-3753-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajaei S, Rigdon J, Crowe S, Tremmel J, Tsai S, Assimes TL. Breastfeeding duration and the risk of coronary artery disease. Journal of Women's Health. 2019;28(1):30–6. 10.1089/jwh.2018.6970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lancet T. Breastfeeding: achieving the new normal. The Lancet. 2016;387(10017):404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parashar M, Singh S, Kishore J, Patavegar BN. Breastfeeding Attachment and Positioning Technique, Practices, and Knowledge of Related Issues Among Mothers in a Resettlement Colony of Delhi. ICAN: Infant, Child, & Adolescent Nutrition. 2015;7(6):317–22. [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Infant and young child feeding: model chapter for textbooks for medical students and allied health professionals. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radzewicz E, Milewska M, Mironczuk-Chodakowska I, Lendzioszek M, Terlikowska K. Breastfeeding as an important factor of reduced infants' infection diseases. Progress in Health Sciences. 2018;8(2):70–4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) [Ethiopia] and ICF. 2019. Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey 2019: Key Indicators. Rockville, Maryland, USA: EPHI and ICF. [Google Scholar]

- 14.da Silva Santos KJ, Santana GS, de Oliveira Vieira T, Santos CAdST, Giugliani ERJ, Vieira GO. Prevalence and factors associated with cracked nipples in the first month postpartum. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2016;16(1):209 10.1186/s12884-016-0999-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goyal RC, Banginwar AS, Ziyo F, Toweir AA. Breastfeeding practices: positioning, attachment (latch-on) and effective suckling–a hospital-based study in Libya. Journal of Family and Community Medicine. 2011;18(2):74 10.4103/2230-8229.83372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.UNICEF, WHO, World Bank, UN DESA/Population Division. Levels and Trends in Child Mortality. UNICEF; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sankar MJ, Sinha B, Chowdhury R, Bhandari N, Taneja S, Martines J, et al. Optimal breastfeeding practices and infant and child mortality: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta paediatrica. 2015;104:3–13. 10.1111/apa.13147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joshi H, Magon P, Raina S. Effect of mother–infant pair's latch-on position on child's health: A lesson for nursing care. Journal of family medicine and primary care. 2016;5(2):309 10.4103/2249-4863.192373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dasgupta U, Mallik S, Bhattacharyya K, Sarkar J, Bhattacharya S, Halder A. Breast feeding practices: positioning attachment and effective suckling-A hospital based study in West Bengal/Kolkata. Indian Journal of Maternal and Child Health. 2013;15(1):10. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thakre SB, Thakre SS, Ughade SM, Golawar S, Thakre AD, Kale P. The Breastfeeding Practices: The Positioning and Attachment Initiative Among the Mothers of Rural Nagpur. Journal of Clinical & Diagnostic Research. 2012;6(7). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tiruye G, Mesfin F, Geda B, Shiferaw K. Breastfeeding technique and associated factors among breastfeeding mothers in Harar city, Eastern Ethiopia. International breastfeeding journal. 2018;13(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kishore MSS, Kumar P, Aggarwal K A. Breastfeeding knowledge and practices amongst mothers in a rural population of North India: a community-based study. Journal of tropical pediatrics. 2008;55(3):183–8. 10.1093/tropej/fmn110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh S, Bhattarai S, Paudel I, Khanal V, Ghimire AJHR. Breastfeeding practices in occupational castes of Sunsari district of Nepal. 2013;11(3):219–23. [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. Womens breast feeding practice counsling. world health organization; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization. Breastfeeding counselling a training course. 2014.

- 26.Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health. Integrated Management of Newborn and Childhood Illness, Part 2. Blended Learning Module for the Health Extension Programme. 2011.

- 27.Degefa N, Tariku B, Bancha T, Amana G, Hajo A, Kusse Y, et al. Breast Feeding Practice: Positioning and Attachment during Breast Feeding among Lactating Mothers Visiting Health Facility in Areka Town, Southern Ethiopia. International journal of pediatrics. 2019;2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization, Unicef. Breastfeeding counselling: a training course. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagendra K, Shetty P, Rudrappa S, Jaganath S, Nair R. Evaluation of breast feeding techniques among postnatal mothers and effectiveness of intervention: Experience in a tertiary care centre. Sri Lanka Journal of Child Health. 2017;46(1). [Google Scholar]

- 30.El-Khedr SM, Lamadah SM. Knowledge, attitude and practices of Saudi women regarding breastfeeding at Makkah al Mukkaramah. J Biol Agriculture Health Care. 2014;4:56–65. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paudel D, Giri S. Breast feeding practices and associated factors in Bhaktapur District of Nepal: A community based cross-sectional study among lactating mothers. Journal of the Scientific Society. 2014;41(2):108. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tella K, Guruvare S, Hebbar S, Adiga P, Rai L. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of techniques of breast-feeding among postnatal mothers in a coastal district of Karnataka. International Journal of Medical Science and Public Health. 2016;5(1):28–34. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(SAV)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.