Abstract

Objective:

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to estimate the pooled magnitude of birth asphyxia and its determinants in Ethiopia.

Methods:

The databases, including PubMed, Medline, CINAHL, EMBASE, and other relevant sources, were used to search relevant articles. Both published and unpublished studies, written in English and carried out in Ethiopia, were included in the study. Quality of evidence was assessed by the relevant of the Joanna Briggs Institute tool. RevMan v5.3 statistical software was used to undertake the meta-analysis using a Mantel-Haenszel random-effects model. Heterogeneity was evaluated using the Cochran Q test, and I2 statistics was considered to assess its level. The outcome was measured using a 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results:

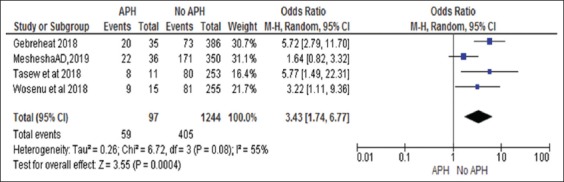

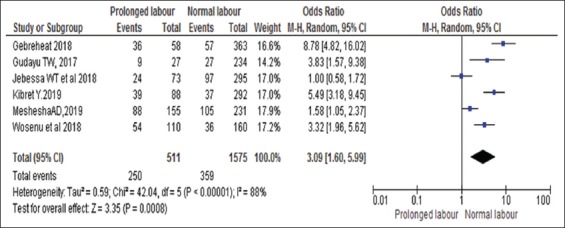

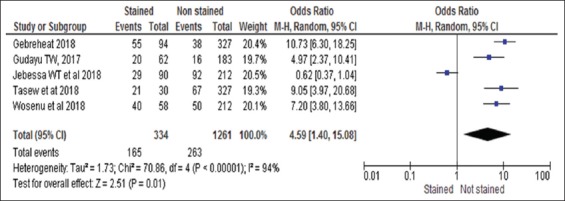

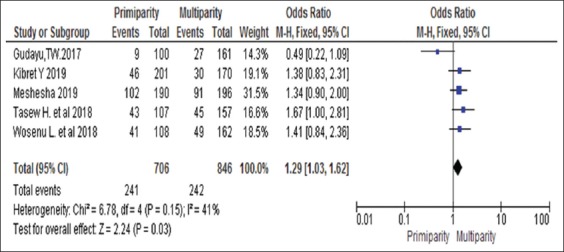

The pooled prevalence of birth asphyxia was 22.8% (95% CI: 13–36.8%]. Illiterate mothers (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]; 1.96, 95% CI: 1.44–2.67), antepartum hemorrhage (APH) (AOR; 3.43, 95% CI: 1.74–6.77), cesarean section (AOR; 3.66, 95% CI: 1.35–9.91), instrumental delivery (AOR; 2.74, 95% CI: 1.48–5.08), duration of labor (AOR; 3.09, 95% CI: 1.60–5.99), pregnancy induced hypertension (AOR; 4.35, 95% CI: 2.98–6.36), induction of labor (AOR; 3.69, 95% CI: 2.26–6.01), parity (AOR; 1.29, 95% CI: 1.03–1.62), low birth weight (LBW) (AOR; 5.17, 95% CI: 2.62–10.22), preterm (AOR; 3.98, 95% CI: 3.00–5.29), non-cephalic presentation (AOR; 4.33, 95% CI: 1.97–9.51), and meconium staining (AOR; 4.59, 95% CI: 1.40–15.08) were significantly associated with birth asphyxia.

Conclusion:

The magnitude of birth asphyxia was very high. Maternal education, APH, mode of delivery, prolonged labor, induction, LBW, preterm, meconium-staining, and non-cephalic presentation were determinants of birth asphyxia. Hence, to reduce birth asphyxia and associated neonatal mortality, attention should be directed to improve the quality of intrapartum service and timely communication between the delivery team. In addition, intervention strategies aimed at reducing birth asphyxia should target the identified determinants.

Keywords: Birth asphyxia, determinant, Ethiopia, newborn

Introduction

Neonatal asphyxia is defined as the failure of initiating and maintaining of breathing at birth.[1,2] Worldwide, more than 1 million neonatal mortality occurred due to birth asphyxia every year.[3,4] A diagnosis of asphyxia is established, when the newborn has a <7 APGAR score at 1st or 5th min after birth.[1,5,6] The acidity of umbilical cord blood can also indicate infants’ oxygen shortage.[5,6] Birth asphyxia results in impairment of tissue perfusion and then yielding to hypoxemia and hypercarbia.[7-9] It is due to the newborn fail to breath normally, which leads to decreased oxygen perfusion to various organs.[5,10,11]

Globally, an estimated 4 million newborns die in the neonatal period; 3 million of them died within 7 days.[12] This accounts for 46% of under-five mortality[13-15] and estimated to increase to 52% in 2030.[16,17] More than 99% of neonatal mortality occurs in developing countries.[18] Neonatal asphyxia is responsible for 42 million disability-adjusted life years.[1,3,10,19-26] The proportion of birth asphyxia is 2 per 1000 births in developed countries but more than 10 times higher in developing countries, where the setting with limited access to quality maternal and neonatal care.[9] Birth asphyxia contributes to a significant burden of neonatal mortality and morbidities. It may result in multi-organ dysfunctions or death. Moreover, survivors of neonatal asphyxia and its main complication (hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy) may suffer from epileptic disorder, cerebral palsy, mental retardation, blindness, hearing, learning, and behavioral disabilities.[3,9,19,23]

In developing countries, newborns had a high chance of being asphyxiated and stillbirth.[25] The available evidence on neonatal mortality rates (NMR) ranged from 0.2% to 64.4% in these settings.[27] The majority of neonatal mortality happened in Asia 39% and Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) 38%. Around 70–80% of these neonatal deaths occur due to preventable and treatable conditions with access to simple, affordable interventions.[12-28] Ethiopia is among countries accounting for more than half of newborn deaths in developing counties.[13-18] Birth asphyxia, septicemia, and complications of preterm birth, jaundice, meningitis, and tetanus are the main cause of neonatal mortality in SSA.[29,30] According to the Ethiopian demographic and health survey, the NMR was 29 out of 1000 live births,[31] and more than 50% of neonatal deaths occurred within the 1st day of life.[17] A complication of prematurity, neonatal asphyxia, and neonatal sepsis were the three common causes of newborn death in Ethiopia.[32-36]

Multiple published studies showed that poor antenatal care (ANC),[37,38] cesarean section, meconium-stained amniotic fluid (MSAF), preterm birth, preeclampsia or eclampsia, and instrumental delivery were major contributing factor for birth asphyxia.[39,40] Occurrences of more serious complications and limited access to quality intrapartum care increased the burden and magnitude of asphyxia in resources limited countries.[23]

For effective health care to be achieved, attention has to be directed to reduce neonatal deaths secondary to birth asphyxia.[38] Supporting with basic newborn resuscitation alone reduce about 30% of intrapartum-related deaths.[1,2,41-43] Moreover, 1-day Helping Babies Breath training can improve the capacity of birth attendants but its implementation of the real action is uncertain.[44] Furthermore, interventions directed to birth asphyxia are less dependent on technology and commodities than trained people.[45] Therefore, improving skills of birth attendance, emergency obstetric care and retraining of this personnel with access to resuscitation equipment is crucial for reductions of mortality due to birth asphyxia.[25,28,46]

Although promising advancement in maternal and childcare occur in the past 10 years, prenatal asphyxia still remains as the main cause of neonatal morbidities and mortality.[38,47-49] With an accelerated increment in facilities-based delivery, attention has to shift toward the quality of service as poor quality would further increase the burden of birth asphyxia.[2] In SSA, including Ethiopia, the main challenges to reducing birth asphyxia are the lack of skilled workers and resuscitation equipment.[46] Evidence pinpointed that birth attendance has insufficient knowledge of birth asphyxia and poor skills in newborn resuscitation.[50] To the best of our knowledge, there is a lack of compressive and solicited evidence for determinants of birth asphyxia in this country. Therefore, the main aim of this meta-analysis was to determine the pooled magnitude of birth asphyxia and its determinants in Ethiopia.

The review questions were:

What was the pooled estimate of birth asphyxia in Ethiopia?

What were the main determining factors of birth asphyxia in Ethiopia?

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis process, identification, screening, and eligibility assessment of full articles were carried out according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement[51] [Additional file 1]. The review protocol was registered in an international prospective register of systematic Review (PROSPERO ID: CRD42018105467). This can be accessed from http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display record.php?ID: CRD 4201 810 5467.

Searching strategies

The databases, including PubMed, Medline, CINAHL, EMBASE, and other relevant sources including Google search engine, Google Scholar, and World Health Organization websites were used to search relevant articles. The following keywords were served as search strings (a) population (newborn, neonate, and fetus), (b) outcome (birth asphyxia, perinatal asphyxia, intrapartum asphyxia, asphyxia neonatorum, perinatal suffocation, suffocation, APGAR score, determinants, associated factors, correlates, predictors, and risk factors), (c) study design (observational studies), and (d) setting (Ethiopia). Finally, all studies which are in agreement with the review title were retrieved and screened for inclusion criteria [Additional file 2].

Eligibility criteria

All studies with cross-sectional, cohort, and case–control study design and survey results were eligible in this meta-analysis. However, case series and reports were excluded from this meta-analysis. Articles with the main aim of determining the proportion of its determinants of birth asphyxia within Ethiopia were considered. Both facility and community-based articles were also included. Both published and unpublished studies at any time point until the last date of search (June 2, 2019), written in the English language and fulfill all other criteria were eligible in the selection process.

Studies screening and selection process

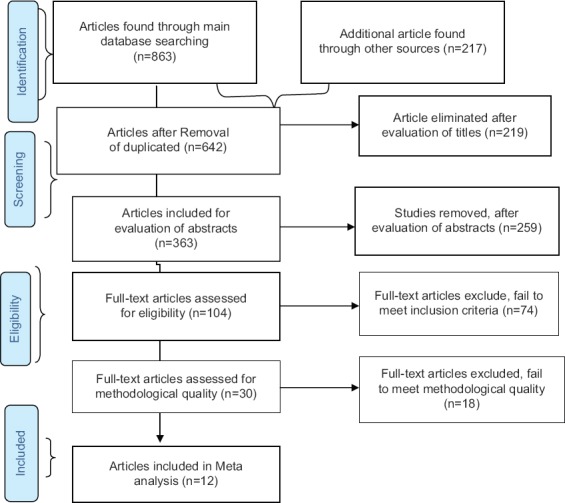

With the possible and appropriate capacity, online documents from the main dataset or directory were transferred into ENDNOTE reference manager software version X8. Then, the articles were collected into a single folder to find duplicates files and removed with the above software. After that, two authors (GT and AD) were separately screened the articles based on preset inclusion criteria. Through title screening, the studies that mentioned birth asphyxia were nominated for abstract screening. Consequently, studies that fulfill eligibility criteria with titles and abstracts were retrieved for full-text screening. Then, full-text screenings were carried out with two independent authors (AD and GT). In any disagreement between the first two authors, the third (AS) was asked to reach into the final decision. The studies screening process based on PRISMA guidelines follows the diagram, as shown in Figure 1.[51]

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis 2009 flow diagram illustrating the screening process for the meta-analysis in identifying the determinant of birth asphyxia in Ethiopia

Critical appraisal of studies

Studies were critically assessed for the validity of results. To ensure the methodological and evidence quality of the studies, we used the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) appraisal tool for observational studies.[52] This JBI critical appraisal checklist had nine questions to assess prevalence data (Q1-Q9), which mainly addresses the methodological area of every article. The results of two authors (GT and AD) with consulting the third author (AS) (in case of discrepancy in the first two authors) were reached into the final judgment. Then, articles with positive answers (yes) for more than 50% of the checklists (i.e., yes for five or more) were included in this meta-analysis. Particular attention was focused on the appropriateness of the design, sampling techniques, data collection, objective, statistical analysis, and any sources of bias [Additional file 3].

Data extraction

Based on the inclusion criteria, two authors (AD and AS) set an extraction template in the Microsoft Excel sheet (2013). Then, the reviewers independently extracted information from all eligible publications. The study description table was formulated to summarize the study design, sample, population, aim, key finding (prevalence of birth asphyxia), and secondary outcome (determinants) [Table 1]. The extracted numerical data were documented and stored in a Microsoft Excel separate sheet.

Table 1.

Describe the characteristics of included studies for outcome variables in the systematic review and meta-analysis

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

A summary table was prepared to describe the characteristics of the included studies. The quantitative data were extracted using Microsoft Excel. Then, data were moved into comprehensive meta-analysis (CMA)[53] and RevMan v5.3 statistical software for the meta-analysis. The pooled prevalence of birth asphyxia was calculated with CMA statistical software, while the factors associated with birth asphyxia were analyzed using RevMan software. The data analysis was performed by AD and GT. The Cochran Q test was applied to find out the occurrence of significant statistical heterogeneity and the level was measured using I2 statistics. When the included studies have high heterogeneity, we used a random-effects model. Sub-group analysis was also conducted considering the APGAR score at the 1st min and 5 min. Any bias related to publication was checked with a funnel plot.

Results

Search results

From 1080 articles retrieved through main databases and direct searches, 438 studies were removed due to duplication through ENDNOTE citation manager. Then, 478 studies were excluded after the title and abstract screening. Full publications of 104 articles were checked in detail for the presence of one of the outcomes variables, and 74 studies were removed. The remaining 30 studies undergone a critical appraisal and 18 studies were excluded in the final meta-analysis because of relative poor method related quality, inconsistency, and unavailability of the data. Finally, 12 publications were included in the pooled estimation of the magnitude of birth asphyxia and eight studies were considered for the analysis of factors associated with birth asphyxia [Figure 1].

Characteristics of studies

Twelve articles with 17147 newborns and 2328 cases of birth asphyxia were incorporated in meta-analysis. Among the studies included in the final analysis, seven were cross-sectional, four were case–control, and the others were prospective cohort. All included studies had sample sizes ranged from 154 to 9738. All articles were written in English. The characteristics of included articles in the meta-analysis were described in the following [Table 1].[54-64]

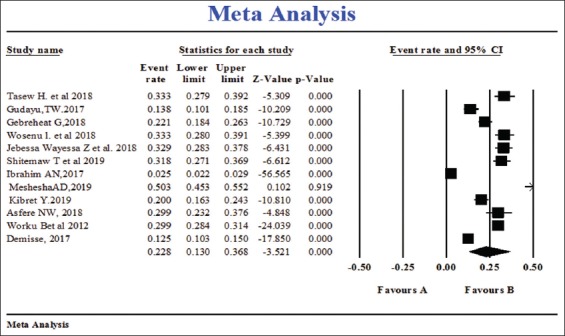

The prevalence of birth asphyxia

The pooled proportion of birth asphyxia in Ethiopia was found to be 22.8% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 13–36.8%), as shown in Figure 2. In sub-group analysis, the prevalence of birth asphyxia in the 1st min was 30.4% (95% CI: 24.6–37%), and at the 5th min was 14.6% (95% CI: 4.3–39.5%).

Figure 2.

Overall pooled estimation of birth asphyxia using the random-effect model in Ethiopia

Determinants of birth asphyxia

The present meta-analysis found various determinants for birth asphyxia in Ethiopia. Maternal illiteracy, low birth weight (LBW), antepartum hemorrhage (APH), preterm births, newborn with MSAF, cesarean section delivery, prolonged duration of labor, instrumental delivery, non-cephalic fetal presentation, and induction or augmentation of labor were found to have a statistically significant association with birth asphyxia. However, ANC use, parity, and maternal anemia were not significantly associated with the outcome variable [Figures 3-16].

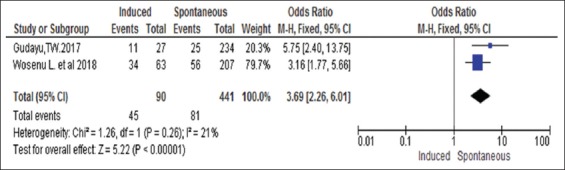

Figure 13.

Association between induction and augmentation of labor with birth asphyxia in Ethiopia

Figure 16.

Association between antenatal care follow-up with birth asphyxia in Ethiopia, 2019

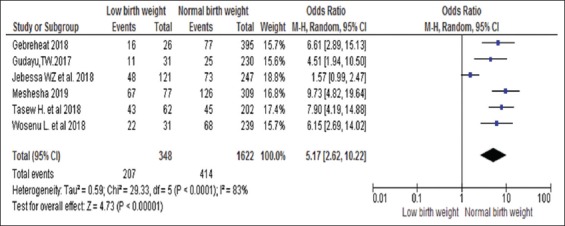

LBW

In this meta-analysis, LBW (<2.5 kg) found a statistically significant association with birth asphyxia with adjusted odds ratio (AOR; 5.17, 95% CI: 2.62–10.22). These indicated that LBW newborns were 5 times more likely to be affected with birth asphyxia compared with their counterparts. Despite the presence of heterogeneity between the studies, LBW was associated with birth asphyxia, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Association between low birth weights with birth asphyxia in Ethiopia

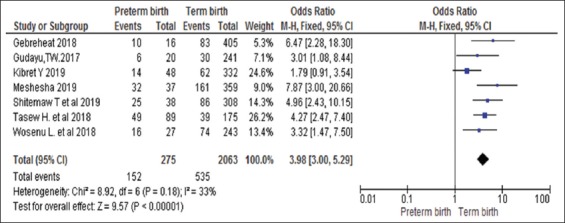

Preterm

According to this meta-analysis, preterm births were found as significant determinants of birth asphyxia. Babies born before 37 weeks of gestation (preterm) have an increased odds of experiencing birth asphyxia with three folds as compared to infants born after term gestations (AOR; 3.98, 95% CI: 3.00–5.29) [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Association between preterm births with birth asphyxia in Ethiopia

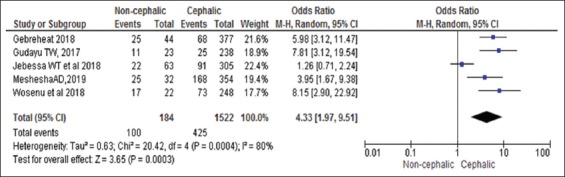

Fetal presentation

According to this meta-analysis, non-cephalic fetal presentation was significantly associated with birth asphyxia. Fetuses who present in non-cephalic ways had more risk of being affected with birth asphyxia (AOR; 4.33, 95% CI: 1.97–9.51) [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Association between non-cephalic fetal presentations with birth asphyxia in Ethiopia

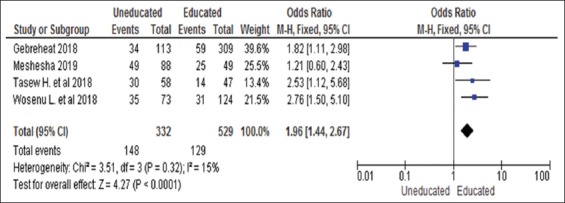

Maternal education

Maternal education level has a statistically significant association with birth asphyxia. Illiterate women were more likely to give asphyxiated newborn when compared with mothers who have attended at least primary and above education level (AOR; 1.96, 95% CI: 1.44–2.67) [Figure 6] and found a statistically significant association with birth asphyxia.

Figure 6.

Association between maternal educations with birth asphyxia in Ethiopia

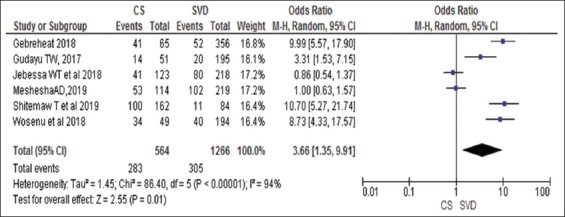

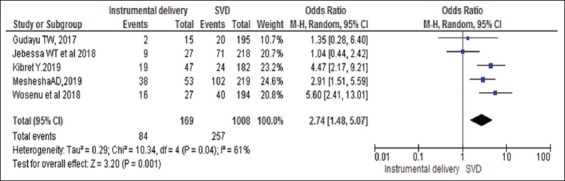

Mode of delivery

Newborn delivered through cesarean section had about 4 times the chance of experiencing severe asphyxia than newborns delivered with spontaneous vaginal birth (AOR; 3.66 [95% CI: 1.35–9.91]) [Figure 7]. Similarly, newborns delivered by assisting instrumental delivery were 2.7 times more likely to be asphyxiated than newborns delivered through spontaneous vaginal mode (AOR; 2.74, 95% CI: 1.48–5.08) [Figure 8]. Giving birth through a cesarean section or instrumental delivery was more likely to expose their newborn for birth asphyxia as compared with newborn delivered through spontaneous vaginal delivery.

Figure 7.

Association between cesarean section with birth asphyxia in Ethiopia

Figure 8.

Association between instrumental deliveries with birth asphyxia in Ethiopia

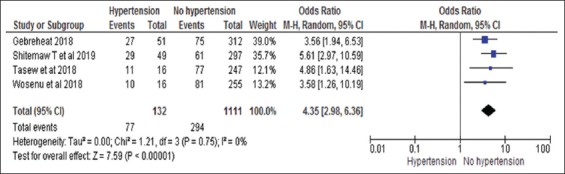

Hypertension during pregnancy

Having hypertensive disorders of pregnancy showed a significant association with the outcome variable. Mothers who had preeclampsia or eclampsia have 4 times the chance of giving asphyxiated newborn than mothers without these disorders (AOR; 4.35, 95% CI: 2.98–6.36) [Figure 9].

Figure 9.

Association between hypertension during pregnancy with birth asphyxia in Ethiopia

APH

The presence of APH was found to have a statistically significant association with birth asphyxia. Neonates from mothers with APH were at high risk of being asphyxiated than newborns from mothers without APH (AOR; 3.43, 95% CI: 1.74–6.77) [Figure 10].

Figure 10.

Association between antepartum hemorrhages with birth asphyxia in Ethiopia

Prolonged duration of labor

The prolonged duration of labor was found as one of the determinants of birth asphyxia. Baby born after a prolonged duration of labor had about 3 times more likely to experience asphyxia than those born in the normal duration of labor (OR; 3.09, 95% CI: 1.60–5.99) [Figure 11].

Figure 11.

Association between duration of labor with birth asphyxia in Ethiopia

MSAF

MSAF was found to have a statistically significant association with birth asphyxia. Newborn delivered with MSAF were 4 times more likely to be asphyxiated as compared with those delivered with clear fluids (AOR; 4.59, 95% CI: 1.40–15.08) [Figure 12].

Figure 12.

Association between meconium-stained amniotic fluids with birth asphyxia in Ethiopia

Induction of labor

Newborns delivered after induction or augmentation labor to facilitate the delivery process had almost 4 times the chance of suffering from birth asphyxia as compared with their counterparts (AOR; 3.69, 95% CI: 2.26–6.01) [Figure 13].

Parity

Babies born from primipara mothers also had a higher chance of getting birth asphyxia than newborns from multipara mothers (AOR; 1.29, 95% CI: 1.03–1.62) [Figure 14].

Figure 14.

Association between parity with birth asphyxia in Ethiopia

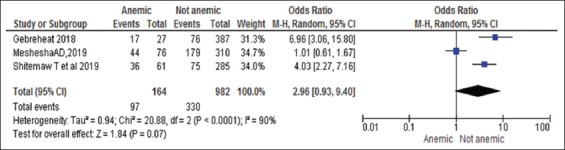

Anemia

Newborn babies from anemic mothers had a chance of giving asphyxiated babies than non-anemic mothers, but it was not statistically significant association (AOR; 2.96, 95% CI: 0.93, 9.40) [Figure 15].

Figure 15.

Association between maternal anemia with birth asphyxia in Ethiopia

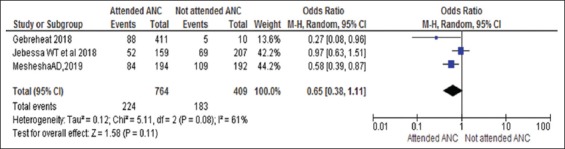

Use of ANC follow-up

Women who had ANC follow-up were 35% less likely to have asphyxiated babies than women who had no visit; however, there was no statistical association (AOR; 0.65, 95% CI: 0.38–1.11) [Figure 16].

Discussion

The present finding indicates that maternal education, APH, caesarian section, instrumental delivery, prolonged duration of labor and induction or augmentation, mode of delivery, being primiparous, LBW, preterm births, MSAF, and non-cephalic presentations were associated with birth asphyxia in Ethiopia. We found out that nearly one-fourths of the newborn were suffering from birth asphyxia in Ethiopia. However, in this analysis, maternal anemia and current use of ANC were not associated with birth asphyxia. The present finding provides important information because; to the best of our knowledge, this paper is the first meta-analysis with regard to determinants of birth asphyxia.

The present meta-analysis provides a summary of available compressive evidence of birth asphyxia and its determinant in the country. Maternal education and prevention of APH are believed to decrease birth asphyxia.[65,66] In current circumstances specifically, in developing countries, where maternal illiteracy is high, it is clear that mothers may not use the prevention strategies as they had inadequate awareness about the burden of birth asphyxia and the determining factors. Therefore, there is a need to refocus the attention to improve birth outcomes with quality intrapartum service including proper resuscitation and early detection of the preventable factors of birth asphyxia in resource-limited countries, particularly in Ethiopia. With regard to the association of APH with birth asphyxia, this may be explained by the fact that there is a reduced blood movement from the placenta to the fetus, resulting in hypoxemia and lead to asphyxia or stillbirth if maternal transfusion is delayed at the time of delivery.

According to present meta-analysis, cesarean sections, instrumental deliveries, induction or augmentations, and prolonged durations of labor were found statistically significant with neonatal asphyxia. This finding was consistent with the different studies conducted in other settings.[47,67-74] The burdens related to birth asphyxia may be related to instrumental delivery because of prolonged labor and delayed interventions so that close monitoring of labor processes, early detection of the main complications, and timely appropriates decision and avoiding unnecessary indications for cesarean section are essential to reducing the burden of birth asphyxia.

Furthermore, preeclampsia or eclampsia has found a statistically significant association with birth asphyxia. The finding is in agreement with evidence in Africa such as Ghana and Egypt.[39,68,70] This may be due to the reduction of blood follow, nutrients and oxygen movement to the fetus, which may increase the risk of in intrauterine development restriction, which may result in perinatal asphyxia. In addition, MSAF was found as a determinant of birth asphyxia. This was in agreement with studies from different countries.[69,73-78] The possible reason may be related to inhalation of MSAF, which causes irritation and inflammation of the lung tissues or may obstruct the airway further inducing hypoxia and birth asphyxia.

Moreover, LBW and pre-term births were found to be significant determinants of birth asphyxia, which was similar to different findings in many settings.[10,39,78-81] In fact, much of LBW newborns are more likely to be pre-term that they are not able to produce adequate surfactant and prone to multiple morbidities, including organ system immaturity, including the inability of initiation of breathing, face challenges in cardiopulmonary transition, and finally, develop birth asphyxia.[75,77] Moreover, a non-cephalic fetal presentation was found independent predictor of birth asphyxia and it is in agreement with other articles in different countries.[6,10,79] In fact, non-cephalic presentation has long been well known to face greater hazards during the process of birth including birth asphyxia, birth trauma, and death. This may be because fetuses presenting with non-cephalic way are more likely to have other associated problems such as umbilical cord prolapsed and head entrapment that predispose them to birth asphyxia.

Limitations and strengths

The present review had certain limitations. The first one was not including qualitative studies in the review, which might identify other determinants of birth asphyxia or might support the quantitative findings. Second, conducting meta-analysis despite the heterogeneity between the included studies might affect the findings. Third, the search was only limited to articles published in the English language. Finally, despite the incorporation of studies from different parts of the country, the representativeness of the population is not as strong as the studies were observational in nature and the majority of them were conducted among newborns admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit. This meta-analysis also has strengths such as the selection and inclusion of both published and unpublished literature which has the potential to minimize publication bias. Moreover, our search strategy was extensive using multiple reputable databases and search engines.

Conclusion

The pooled magnitude of birth asphyxia was very high. Maternal education, APH, caesarian section, instrumental delivery, prolonged duration of labor, induction or augmentation, MSAF, and non-cephalic presentation were factors associated with birth asphyxia. LBW and preterm births were found as fetal related determinants of birth asphyxia. Hence, to reduce birth asphyxia and associated neonatal mortality, attention should be directed to improve the quality of intrapartum service and timely communication between the delivery team. In addition, intervention strategies that aim to reduce birth asphyxia should target the identified factors.

Authors’ Contributions

AD and AS initiated and formulated this meta-analysis. AD conducted activities from initiation to finalization of the manuscript. AD, AS, and GT build-up the search strategies, meta-analysis, and interpretation of the findings. All authors thoroughly revised the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the School of Nursing and Midwifery, College of Health and Medical Science, Haramaya University for their non-financial support and cooperation for facilitation of systematic training.

Additional file 1: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols; recommended items to address in a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol

Title: Determinants of birth asphyxia among newborns in Ethiopia: A systematic review and metal analysis

*It is strongly recommended that this checklist be read in conjunction with the PRISMA-P Explanation and elaboration (cite when available) for important clarification on the items. Amendments to a review protocol should be tracked and dated. The copyright for PRISMA-P (including checklist) is held by the PRISMA-P Group and is distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence 4.0.

From: Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart L, PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015 Jan 2; 349(jan02 1):g7647.

Additional file 2: Search strategy

Title of the review: Determinants of birth asphyxia among live birth newborns in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Additional file 3: Quality assessment of studies using JBI's critical appraisal tools designed for observational studies

Title: Determinants of birth asphyxia among live birth newborns in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Guidelines on Basic Newborn Resuscitation. Geneva: WHO Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manu A, Arifeen S, Williams J, Mwasanya E, Zaka N, Plowman BA, et al. Assessment of facility readiness for implementing the WHO/UNICEF standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities experiences from UNICEF's implementation in three countries of South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:531. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3334-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halloran DR, McClure E, Chakraborty H, Chomba E, Wright LL, Carlo WA. Birth asphyxia survivors in a developing country. J Perinatol. 2009;29:243–9. doi: 10.1038/jp.2008.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawn JE, Manandhar A, Haws RA, Darmstadt GL. Reducing one million child deaths from birth asphyxia a survey of health systems gaps and priorities. Health Res Policy Syst. 2007;5:4. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-5-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ilah BG, Aminu MS, Musa A, Adelakun MB. Prevalence and risk factors for perinatal asphyxia as seen at a specialist hospital in Gusau, Nigeria. Sub-Saharan African J Med. 2015;2:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.West BA, Opara PI. Perinatal asphyxia in a specialist hospital in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Niger J Paediatr. 2013;40:206–10. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spector JM, Daga S. Perspectives preventing those so-called stillbirths. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:2007–8. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.049924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enweronu-Laryea C, Dickson KE, Moxon SG, Simen-Kapeu A, Nyange C, Niermeyer S, et al. Basic newborn care and neonatal resuscitation:A multi-country analysis of health system bottlenecks and potential solutions. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15(Suppl 2):S4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-15-S2-S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krakauer MG, Gowen JC. StatPearlsTreasure Island. Florida: StatPearls Publishing; 2019. Birth Asphyxia-StatPearls-NCBI Bookshelf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aslam HM, Saleem S, Afzal R, Iqbal U, Saleem SM, Shaikh MW, et al. Risk factors of birth asphyxia. Ital J Pediatr. 2014;40:94. doi: 10.1186/s13052-014-0094-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azra Haider B, Bhutta ZA. Birth asphyxia in developing countries:Current status and public health implications. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2006;36:178–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. Child mortality:Countdown to 2015 Tracking Progress in Maternal, Newborn and Child Survival. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.UNICEF. United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME), Levels and Trends in Child Mortality. Report 2015. New York: United Nations Children's Fund; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang H, Liddell CA, Coates MM, Mooney MD, Levitz EC, Schumacher EA, et al. Global, regional, and national levels of neonatal, infant, and under-5 mortality during 1990-2013:A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. Lancet. 2014;384:957–79. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60497-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Monitoring Health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16.UNICEF, WHO, World Bank and U-DPD. Levels and Trends in Child Mortality. UN Plaza, New York: World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bogale TN, Worku AG, Bikis GA, Kebede ZT. Why gone too soon?Examining social determinants of neonatal deaths in Northwest Ethiopia using the three delay model approach. BMC Pediatr. 2017;17:216. doi: 10.1186/s12887-017-0967-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oza S, Lawn JE, Hogan DR, Mathers C, Cousens SN. Neonatal cause-of-death estimates for the early and late neonatal periods for 194 countries: 2000-2013. Bull World Health Organ. 2015;93:19–28. doi: 10.2471/BLT.14.139790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nair J, Kumar VH. Current and emerging therapies in the management of hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy in neonates. Children (Basel) 2018;5:E99. doi: 10.3390/children5070099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bryce J, Boschi-Pinto C, Shibuya K, Black RE. WHO Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group. WHO estimates of the causes of death in children. Lancet. 2005;365:1147–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71877-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stanton C, Lawn JE, Rahman H, Wilczynska-Ketende K, Hill K. Stillbirth rates:Delivering estimates in 190 countries. Lancet. 2006;367:1487–94. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68586-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J. Neonatal survival 1 4 million neonatal deaths :When ?Where ?Why ? Lancet. 2005;365:891–900. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhutta ZA. Learn more about perinatal asphyxia paediatrics in the tropics. In: Farrar J, Hotez PJ, White NJ, editors. Manson's Tropical Infectious Diseases. 23rd ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daripa M, Caldas HM, Flores LP, Waldvogel BC, Guinsburg R, de Almeida MF. Perinatal asphyxia associated with early neonatal mortality:Populational study of avoidable deaths. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2013;31:37–45. doi: 10.1590/s0103-05822013000100007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawn JE, Kerber K, Enweronu-Laryea C, Massee Bateman O. Newborn survival in low resource settings are we delivering? BJOG. 2009;116(Suppl 1):49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riley C, Spies LA, Prater L, Garner SL. Improving neonatal outcomes through global professional development. Adv Neonatal Care. 2019;19:56–64. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0000000000000550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chow S, Chow R, Popovic M, Lam M, Popovic M, Merrick J, et al. A selected review of the mortality rates of neonatal intensive care units. Front Public Health. 2015;3:225. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization. Every Newborn: An Action Plan to End Preventable Deaths:Executive Summary. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Afolabi BM. Sub-Sahara African neonates:Ghosts to statistics. J Neonatal Biol. 2017;6:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salve D, Inamdar IF, Sarawade S, Doibale M, Tambe S, Sahu P. Study of profile and outcome of the newborns admitted in neonatal intensive care unit at tertiary care hospital in a city of Maharashtra. Int J Heal Sci Res. 2015;5:18–23. [Google Scholar]

- 31.ICF and CSA [Ethiopia]. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016: Key Indicators Report. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville Maryland. USA: ICF; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elmi Farah A, Abbas AH, Tahir Ahmed A. Trends of admission and predictors of neonatal mortality:A hospital based retrospective cohort study in Somali region of Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0203314. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Debelew GT, Afework MF, Yalew AW. Determinants and causes of neonatal mortality in Jimma Zone, Southwest Ethiopia:A multilevel analysis of prospective follow up study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e107184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elizabeth UI, Oyetunde MO. Pattern of diseases and care outcomes of neonates admitted in. IOSR J Nurs Heal Sci Ver I. 2015;4:1940–2320. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gebreheat G, Tsegay T, Kiros D, Teame H, Etsay N, Welu G, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of perinatal asphyxia among neonates in general hospitals of Tigray, Ethiopia 2018. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:5351010. doi: 10.1155/2018/5351010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mengesha HG, Sahle BW. Cause of neonatal deaths in Northern Ethiopia:A prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:62. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3979-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chiabi A, Nguefack S, Mah E, Nodem S, Mbuagbaw L, Mbonda E, et al. Risk factors for birth asphyxia in an urban health facility in Cameroon. Iran J Child Neurol. 2013;7:46–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aliyu I, Lawal T, Onankpa B. Prevalence and outcome of perinatal asphyxia:Our experience in a semi-urban setting. Trop J Med Res. 2017;20:161. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dassah ET, Odoi AT, Opoku BK. Stillbirths and very low apgar scores among vaginal births in a tertiary hospital in Ghana:A retrospective cross-sectional analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:289. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Orsido TT, Asseffa NA, Berheto TM. Predictors of neonatal mortality in neonatal intensive care unit at referral hospital in Southern Ethiopia:A retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:83. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2227-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wall SN, Lee AC, Niermeyer S, English M, Keenan WJ, Carlo W, et al. Neonatal resuscitation in low-resource settings :What, who, and how to overcome challenges to scale up ? Int J Gynaecol Obs. 2010;107(Suppl 1):S47–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee AC, Cousens S, Wall SN, Niermeyer S, Darmstadt GL, Carlo WA, et al. Neonatal resuscitation and immediate newborn assessment and stimulation for the prevention of neonatal deaths:A systematic review, meta-analysis and Delphi estimation of mortality effect. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(Suppl 3):S12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-S3-S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chomba E, McClure EM, Wright LL, Carlo WA, Chakraborty H, Harris H. Effect of WHO newborn care training on neonatal mortality by education. Ambul Pediatr. 2008;8:300–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Odjidja EN. Making every baby count :Reflection on the Helping Babies Breathe Program to reduce birth asphyxia in Sub-Saharan Africa;helping, the Breathe, babies. S Afr J Child Health. 2017;11:61–3. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Knippenberg R, Lawn JE, Darmstadt GL, Begkoyian G, Fogstad H, Walelign N, et al. Neonatal survival series 3 systematic scaling up of neonatal care:What will it take in the reality of countries? Lancet. 2005;365:1087–98. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mukhtar-Yola M, Audu LI, Olaniyan O, Akinbi HT, Dawodu A, Donovan EF. Decreasing birth asphyxia:Utility of statistical process control in a low-resource setting. BMJ Open Qual. 2018;7:e000231. doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2017-000231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Antonucci R, Porcella A, Pilloni MD. Perinatal asphyxia in the term newborn. J Pediatr Neonatal Individ Med. 2014;3:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ellsbury DL, Clark RH, Ursprung R, Handler L, Dodd ED, Spitzer AR. A multifaceted approach to improving outcomes in the NICU:The pediatrix 100 000 babies campaign. Pediatrics. 2016;137:e20150389. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Panthee K, Sharma K, Kalakheti B, Thapa K. Clinical profile and outcome of asphyxiated newborn in a medical college teaching hospital. J Lumbini Med Coll. 2016;4:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mirkuzie AH, Sisay MM, Reta AT, Bedane MM. Current evidence on basic emergency obstetric and newborn care services in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia;a cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:354. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses:The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mueller M, D'Addario M, Egger M, Cevallos M, Dekkers O, Mugglin C, et al. Methods to systematically review and meta-analyse observational studies:A systematic scoping review of recommendations. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18:44. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0495-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, Rothstein H. Comprehensive Meta Analysis. 2004. 1 pp.104 pp. Available from: https://www.meta-analysis.com .

- 54.Tasew H, Gebrekristos K, Kidanu K, Mariye T, Teklay G. Determinants of hypothermia on neonates admitted to the intensive care unit of public hospitals of central zone, Tigray, Ethiopia 2017:Unmatched case-control study. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:576. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3691-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gudayu TW. Proportion and factors associated with low fifth minute apgar score among singleton newborn babies in Gondar University referral hospital;North West Ethiopia. Afr Health Sci. 2017;17:1–6. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v17i1.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wosenu L, Worku AG, Teshome DF, Gelagay AA. Determinants of birth asphyxia among live birth newborns in University of Gondar referral hospital, Northwest Ethiopia:A case-control study. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0203763. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wayessa ZJ, Belachew T, Joseph J. Birth asphyxia and associated factors among newborns delivered in Jimma zone public hospitals, Southwest Ethiopia:A cross-sectional study. J Midwifery Reprod Health. 2018;6:1289–95. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shitemaw T, Yesuf A, Girma M, Sidamo NB. Determinants of poor apgar score and associated risk factors among neonates after cesarean section in public health facilities of Arba Minch town, Southern Ethiopia. EC Paediatr. 2019;8:61–70. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ibrahim NA, Muhye A, Abdulie S. Prevalence of birth asphyxia and associated factors among neonates delivered in dilchora referral hospital, in dire dawa, Eastern Ethiopia. Clin Mother Child Health. 2018;14:90. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meshesha AD, Azage M, Worku E, Gebre G. Determinants of Birth Asphyxia Among Newborns in Amhara National Regional State Referral Hospitals, Ethiopia. bioRxiv Prepr First Posted Online:Pre Print Document. 2019:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kibret Y, Hailu G, Angaw K. Determinants of birth-asphyxia among newborns in dessie town hospitals, North-central Ethiopia. Int J Sex Heal Reprod Health Care. 2018;1:12. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Necho AW, Yesuf A. Neonatal asphyxia and associated factors among neonates on labor ward at debre-tabor general hospital, Debre Tabor town, South Gonder, North centeral Ethiopia. Int J Pregnancy Child Birth. 2018;4:208–12. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Worku B, Kassie A, Mekasha A, Tilahun B, Worku A. Predictors of early neonatal mortality at a neonatal intensive care unit of a specialized referral teaching hospital in. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2012;26:200–7. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Demisse AG, Alemu F, Gizaw MA, Tigabu Z. Patterns of admission and factors associated with neonatal mortality among neonates admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit of University of Gondar Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Pediatric Health Med Ther. 2017;8:57–64. doi: 10.2147/PHMT.S130309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Takai IU, Sayyadi BM, Galadanci HS. Antepartum hemorrhage:A retrospective analysis from a Northern Nigerian teaching hospital. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2017;7:112–6. doi: 10.4103/2229-516X.205819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee AC, Mullany LC, Tielsch JM, Katz J, Khatry SK, LeClerq SC, et al. Risk factors for neonatal mortality due to birth asphyxia in southern Nepal:A prospective, community-based cohort study. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1381–90. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.World Health Organization. WHO Statement on Caesarean Section Rates Caesarean Section Rates at the Hospital Level and the Need for a Universal Classification System. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. pp. 8–90. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shah A, Fawole B, M'imunya JM, Amokrane F, Nafiou I, Wolomby JJ, et al. Cesarean delivery outcomes from the WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health in Africa. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;107:191–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kardana I. Risk factors of perinatal asphyxia in the term newborn at Sanglah general hospital, Bali-Indonesia. Bali Med J. 2016;5:175–8. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ibrahim MH, Asmaa MN. Perinatal factors preceding neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in el-minia locality. Gynecol Obstet (Sunnyvale) 2016;6:403–90. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Altman M, Sandstrom A, Petersson G, Frisell T, Cnattingius S, Stephansson O. Prolonged second stage of labor is associated with low apgar score. Euro J Epidemiol. 2015;30:1209–15. doi: 10.1007/s10654-015-0043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Osuorah CI, Ekwochi U, Asinobi N. Failure to establish spontaneous breathing at birth:A 5-year longitudinal study of newborns admitted for birth asphyxia in Enugu, Southeast Nigeria. J Clin Neonatol. 2018;7:151. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kaye D. Antenatal and intrapartum risk factors for birth asphyxia among emergency obstetric referrals in Mulago hospital, Kampala, Uganda. East Afr Med J. 2003;80:140–3. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v80i3.8683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Milsom I, Ladfors L, Thiringer K, Niklasson A, Odeback A, Thornberg E. Influence of maternal, obstetric and fetal risk factors on the prevalence of birth asphyxia at term in a Swedish urban population. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81:909–17. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2002.811003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Utomo MT. Risk factors for birth asphyxia. Folia Medica Indones. 2009;47:211–4. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vijai B, Babu A, Shyamala DS, Kishore KB. Birth asphyxia;incidence and immediate outcome in relation to risk factors and complications. Int J Res Health Sci. 2014;4:1064–71. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pitsawong C. Risk factors associated with bir th asphyxia in phramongkutklao hospital. Thai J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;19:165–71. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Solayman M, Hoque S, Akber T, Islam MI, Islam MA. Prevalence of perinatal asphyxia with evaluation of associated risk factors in a rural tertiary level hospital. KYAMC J. 2017;8:43–8. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yadav N, Damke S. Study of risk factors in children with birth asphyxia. Int J Contemp Pediatr. 2017;4:518. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lee AC, Darmstadt GL, Mullany LC. Risk factors for birth asphyxia mortality in a community-based setting in Southern Nepal. Pediatrics. 2008;121:1–45. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gane B, Vishnu BB, Rao R, Nandakumar S, Adhisivam B, Joy R, et al. Antenatal and intrapartum risk factors for perinatal asphyxia:A case control study. Curr Pediatr Res. 2013;17:119–22. [Google Scholar]