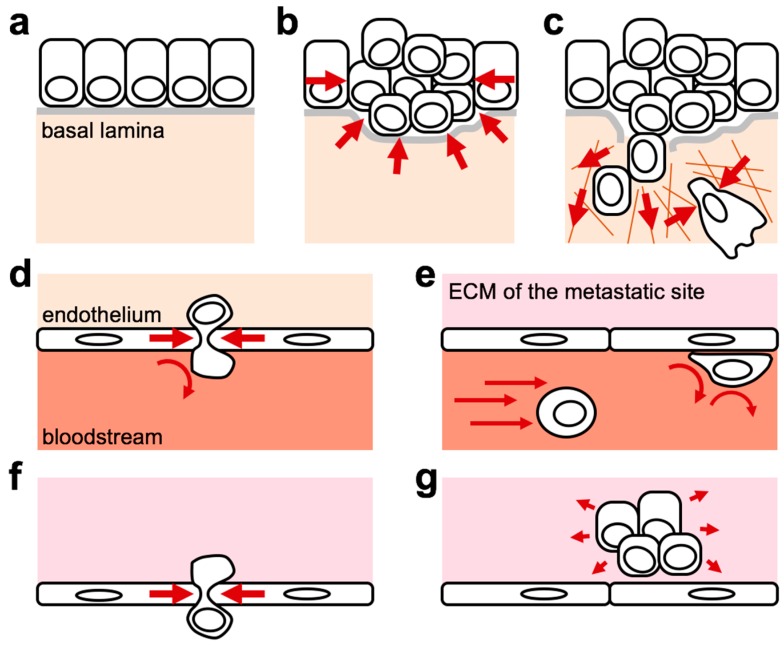

Figure 1.

Cancer cells are exposed to different forces while they undergo metastatic dissemination. The scheme exemplifies the development of a solid tumor originating from an epithelium (a). Transformation and neoplastic growth may increase local crowding and intratumoral pressure (b), activating mechanical competition mechanisms, neoangiogenesis (not shown), and degradation of the basal lamina. Remodeling and stiffening of the extracellular matrix (ECM) in cooperation with cells of the stroma (not shown) provide higher resisting forces, which promotes cell tension, outward cell migration and sustain cancer cell survival, proliferation and tumour-initiating properties (c). Migration within a dense ECM may also cause compressive stresses, leading to DNA ruptures and activation of DNA-damage responses (c). Cells invading the local stroma may reach the vessels and intravasate by physical crossing the endothelial barrier (d). In the blood, disseminating cells lack of adhesion to the ECM and experience shear stresses that may influence their preferential homing to some target organs and the ability of cells to adhere to the endothelium (e). Once cells successfully pass the endothelium and extravasate (f), they reach a novel ECM microenvironment (g) with new mechanical properties (in the example, a softer ECM providing lower resisting forces and thus enabling cells to develop lower traction forces). Red arrows indicate external forces applied on cells by the microenvironment.