Abstract

Adamantinoma-like Ewing sarcoma (ALES) is a rare variant of Ewing sarcoma that is defined by complex epithelial differentiation, including expression of cytokeratin and p40 and frequent keratin pearl formation. In recent years, ALES has been increasingly recognized in the head and neck, where it can mimic a wide range of small round blue cell tumors and basaloid carcinomas. However, there has been persistent controversy regarding whether ALES is best classified and managed as a sarcoma or carcinoma. This review summarizes the characteristic clinical, pathologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular features of ALES with an emphasis on differential diagnosis and tumor classification.

Keywords: Ewing sarcoma, Adamantinoma-like Ewing sarcoma, EWSR1, FLI1, Complex epithelial differentiation

Introduction

Adamantinoma-like Ewing sarcoma (ALES) is a rare and somewhat controversial variant of Ewing sarcoma that was initially described by Bridge et al. in 1999 [1]. While these tumors harbor the t(11;22) translocation and EWSR1-FLI1 gene fusion traditionally regarded as pathognomonic for a diagnosis of Ewing sarcoma, they also demonstrate complex epithelial differentiation, including immunohistochemical expression of high molecular weight cytokeratins and p40 and frequently, overt keratin pearl formation. Indeed, the epithelial differentiation is so well-developed that a subset of identical cases have been reported under the alternate name “carcinoma with Ewing family tumor elements” (CEFTE) [2, 3]. Although ALES was originally described in the extremities and thorax [1, 4–6], this tumor type has since been predominantly recognized in the head and neck. Of the 31 molecularly-confirmed cases published as either ALES or CEFTE to date, 23 (74%) have arisen in head and neck sites [2, 3, 7–16]. In this location, ALES can pose a particularly challenging differential diagnosis with other small round blue cell tumors and basaloid carcinomas. This review aims to present a comprehensive overview of the features of ALES in the head and neck with particular focus on differential diagnosis and tumor classification.

Clinical Features

Twenty-three cases of ALES involving the head and neck have been reported in detail in the literature (Table 1) [2, 3, 7–16]. The vast majority of these tumors have arisen in epithelial organs or mucosal sites, including the parotid gland (n = 8), thyroid gland (n = 6), sinonasal tract (n = 4), and submandibular gland (n = 2); a subset has been centered in soft tissue of the neck (n = 2) and orbit (n = 1). Affected patients have included 13 males and 10 females with a mean age of 37 years (range 7 to 77 years). Interestingly, patient age seems to vary significantly across anatomic site, with a mean age of 52 years in salivary tumors compared to just 26 years in non-salivary tumors. Most ALES cases arising in the thyroid and salivary glands have presented as painless neck masses [2, 3, 8, 10, 11, 14–16], while those in the sinonasal tract and orbit have generally led to symptoms of mass effect including nasal obstruction, proptosis, epistaxis, and orbital pain [7, 8, 13]. One patient with a tumor involving a branch of the vagus nerve in level IV soft tissue presented with Horner syndrome [12].

Table 1.

Clinical and Demographic Features

| Case | Publication | Age | Sex | Site | Presenting symptom | Initial/preliminary diagnosis | Final diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Weinreb et al. [12] | 29 | M | Neck soft tissue | Horner syndrome | PD SCC | ALES |

| 2 | Cruz et al. [2], Eloy et al. [3] | 42 | F | Thyroid gland | Anterior cervical mass | Small cell thyroid CA | CEFTE |

| 3 | Kikuchi et al. [9] | 11 | F | Neck soft tissue | Neck mass | ALES | ALES |

| 4 | Eloy et al. [3] | 24 | M | Thyroid gland | Large thyroid nodule | PD thyroid CA | CEFTE |

| 5 | Lezcano et al. [10], Bishop et al. [8], Rooper et al. [16] | 56 | F | Parotid gland | Painless neck mass | Basal cell ACA | ALES |

| 6 | Bishop et al. [8] | 37 | F | Sinonasal tract | Nasal obstruction and epistaxis | PD SCC | ALES |

| 7 | Bishop et al. [8] | 21 | M | Sinonasal tract | Proptosis | ALES | ALES |

| 8 | Bishop et al. [8] | 7 | F | Orbital soft tissue | Proptosis | Myoepithelial CA | ALES |

| 9 | Bishop et al. [8], Rooper et al. [16] | 40 | F | Parotid gland | Painless neck mass | Basal cell adenoma | ALES |

| 10 | Bishop et al. [8] | 19 | M | Thyroid gland | Neck mass | ALES | ALES |

| 11 | Bishop et al. [8] | 36 | F | Thyroid gland | Goiter | ALES | ALES |

| 12 | Alexiev et al. [7] | 41 | M | Sinonasal tract | Orbital pain and swelling | NUT CA | ALES |

| 13 | Lilo et al. [11], Rooper et al. [16] | 72 | M | Parotid gland | Painful parotid mass | ALES | ALES |

| 14 | Ongkeko et al. [15] | 36 | M | Thyroid gland | Enlarging neck mass | PD thyroid CA | ALES |

| 15 | Rooper et al. [16] | 58 | M | Submandibular gland | Painless neck mass | PD CA | ALES |

| 16 | Rooper et al. [16] | 63 | F | Parotid gland | Rapidly growing parotid mass | PD CA with basaloid features | ALES |

| 17 | Rooper et al. [16] | 77 | M | Submandibular gland | Neck mass | PD CA with basaloid features | ALES |

| 18 | Rooper et al. [16] | 32 | F | Parotid gland | Neck swelling | High grade neuroendocrine CA | ALES |

| 19 | Rooper et al. [16] | 32 | M | Parotid gland | Painless facial mass | PD CA with basaloid features | ALES |

| 20 | Rooper et al. [16] | 41 | M | Parotid gland | Painless neck mass | PD CA with basaloid features | ALES |

| 21 | Rooper et al. [16] | 46 | M | Parotid gland | Rapidly growing tender mass | Merkel cell CA | ALES |

| 22 | Morlote et al. [14] | 20 | F | Thyroid gland | Non-painful left neck mass | ALES | ALES |

| 23 | Madhevan et al. [13] | 18 | M | Sinonasal tract | Nasal mass | Basaloid variant of SCC | ALES |

ACA adenocarcinoma, ALES Adamantinoma-like Ewing sarcoma, CA carcinoma, CEFTE carcinoma with Ewing family tumor elements, F female, M male, PD poorly differentiated, SCC squamous cell carcinoma

Pathologic Features

ALES generally presents as a large tumor, with a mean size of 4.3 cm (range 2.3 to 7.9 cm) [2, 3, 7–16]. While these tumors consistently have infiltrative borders, the extent of invasion differs somewhat by anatomic site, with sinonasal and soft tissue ALES frequently demonstrating extensive involvement and destruction of surrounding structures [7–9, 12] and thyroid and salivary gland ALES largely remaining organ confined [2, 3, 8, 10, 14, 16]. Upon gross examination, ALES tends to have a white to grey, firm, fibrotic, and lobulated cut surface with variable amounts of cystic degeneration and calcifications [2, 9, 10, 12].

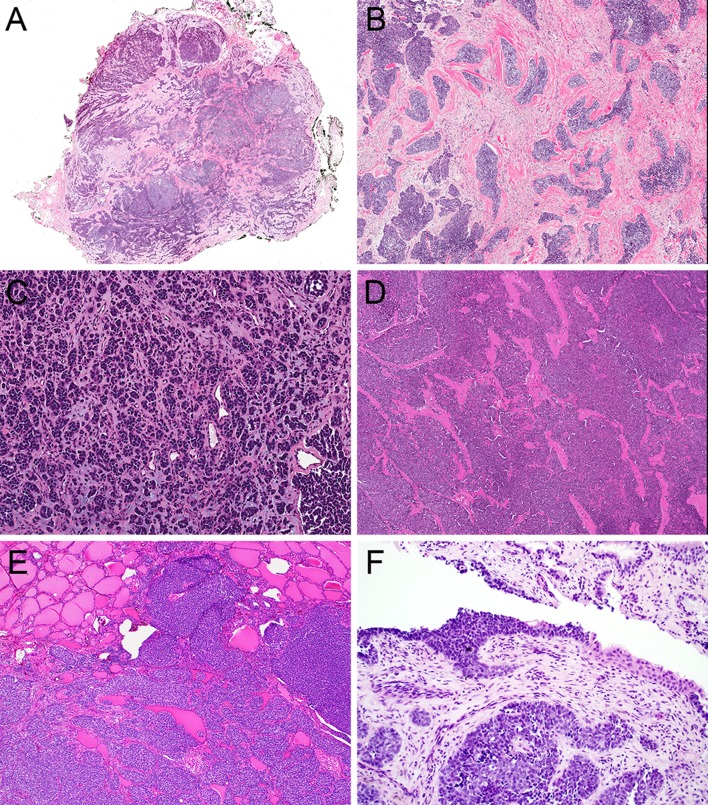

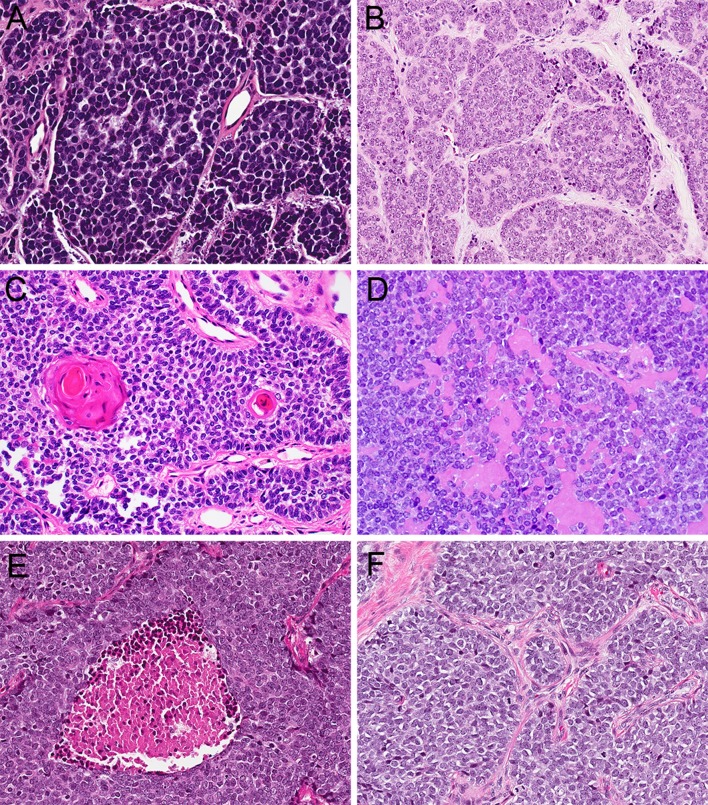

Histologically, ALES is characterized by infiltrative sheets, nests and lobules of basaloid cells embedded in a prominent myxoid, fibromyxoid, or hyalinized stroma (Fig. 1). Occasional sinonasal tumors have shown colonization of surface mucosa, and thyroid tumors frequently grow into existing follicles [7, 8, 14]. While a subset of tumors shows peripheral nuclear palisading and rosette formation (Fig. 2), these features are not uniformly present. Likewise, somewhat abrupt formation of small, compact keratin pearls is only seen in a minority of cases. These features seem to be relatively less common in tumors that occur in the salivary glands than other sites [16]. Tumors tend to have prominent mitoses, with 3 to 20 mitotic figures per 10 high-power fields and easily recognizable zones of necrosis [2, 3, 7–10, 12–16]. Despite these high-grade features, the tumor cells are remarkably uniform with round to oval nuclei that show minimal pleomorphism.

Fig. 1.

ALES is a highly infiltrative tumor (a, 2x) consisting of sheets, lobules, and nests of basaloid tumor cells embedded in fibrous (b, 4x), myxoid (c, 4x), and hyalinized (d, 4x) stroma. Thyroid ALES tend to colonize existing follicular structures (e, 4x) while sinonasal tumors occasionally colonize surface epithelium (d, 10x)

Fig. 2.

ALES is composed of basaloid cells with round to oval nuclei and minimal cytoplasm (a, 20x). A subset of tumors demonstrates rosette formation (b, 20x), peripheral palisading, and keratin pearl formation (c, 20x), with rare production of basement-membrane-like matrix (d, 20x). Tumor cells are uniform and monotonous despite conspicuous necrosis (e, 20x) and an elevated mitotic rate (F, 20x)

Fine needle aspiration (FNA) findings have been characterized in detail in one case, a parotid gland ALES [11]. This tumor produced hypercellular smears comprised of cohesive groups and loose clusters of monotonous basaloid cells with patchy peripheral palisading. Tumor cells had a moderate amount of amphophilic cytoplasm with focal cytoplasmic vacuolation and uniform, round to oval nuclei with rare mitotic figures. A scant amount of metachromatic stroma was present. Although additional detailed cytomorphologic findings are not available, other cases of ALES have been characterized as basaloid neoplasm, follicular neoplasm, or suspicious for malignancy on FNA [2, 10, 14, 15].

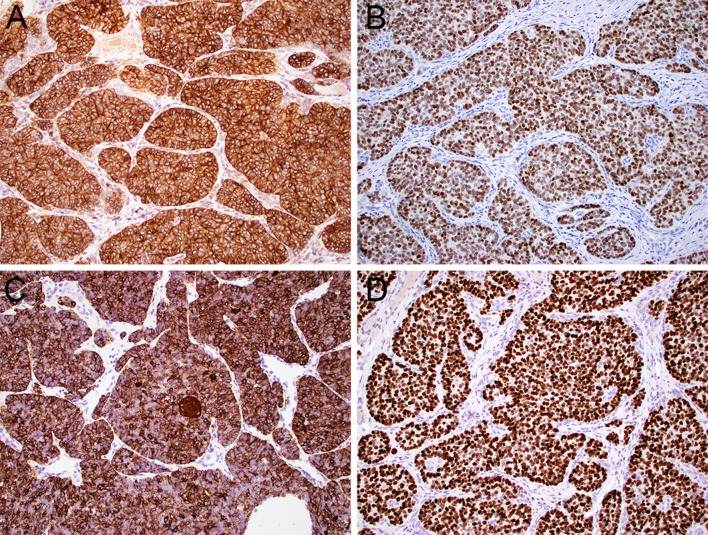

Immunohistochemistry

All reported cases of ALES have demonstrated a characteristic immunohistochemical profile (Table 2). ALES shares the strong, membranous CD99 expression and nuclear NKX2.2 positivity characteristic of conventional Ewing sarcoma [2, 3, 7–19]. But, by definition, this variant also demonstrates positivity for cytokeratin, p63 and p40 (Fig. 3). Although some degree of low molecular weight cytokeratin expression can be seen in up to 30% of conventional Ewing sarcoma [5, 20, 21], the diffuse nature of cytokeratin expression and positivity for high molecular weight cytokeratins is unique in ALES. Likewise, the diffuse positivity for p63 or p40 seen in ALES is uncommon in conventional Ewing sarcoma [22, 23]. ALES also shows variable and usually focal positivity for neuroendocrine markers (most commonly synaptophysin); these stains seem to be more consistently expressed in salivary than non-salivary sites [16]. Additionally, almost all cases of ALES have been negative for S100, SMA, desmin, WT1, and NUT1. Although a subset of cases have shown p16 positivity; in situ hybridization for HPV is always negative [8].

Table 2.

Ancillary testing results

| Case | CK | p63/p40 | Synapto | Chromo | CD99 | NKX2.2 | S100 | Desmin | SMA | NUT1 | EWSR1 FISH | FLI1 FISH | EWSR1-FLI1 PCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | + | + | NA | NA | + | NA | − | − | − | NA | + | NA | + |

| 2 | + | + | − | − | + | NA | − | NA | − | NA | + | + | NA |

| 3 | + | + | F+ | − | + | NA | − | − | − | − | NA | NA | + |

| 4 | + | + | − | − | + | NA | − | NA | NA | NA | + | + | NA |

| 5 | + | + | F+ | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | NA |

| 6 | + | + | − | − | + | NA | + | − | − | − | + | + | NA |

| 7 | + | + | − | − | + | NA | − | − | − | − | + | + | NA |

| 8 | + | NA | NA | NA | + | NA | F+ | − | − | NA | + | + | NA |

| 9 | + | + | F+ | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | NA |

| 10 | + | + | − | − | + | NA | F+ | − | F+ | − | + | + | NA |

| 11 | + | + | + | F+ | + | NA | − | − | − | NA | + | + | NA |

| 12 | + | + | − | − | + | NA | − | − | − | − | + | NA | NA |

| 13 | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | NA | NA |

| 14 | + | NA | − | − | + | NA | − | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | + |

| 15 | + | + | + | F+ | + | NA | NA | − | NA | NA | + | NA | NA |

| 16 | + | + | − | − | + | + | F+ | − | − | − | + | NA | NA |

| 17 | + | + | F+ | F+ | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | NA | NA |

| 18 | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | NA | NA |

| 19 | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | NA | NA | − | + | NA | + |

| 20 | + | + | + | − | + | NA | − | − | NA | − | + | NA | NA |

| 21 | + | + | + | F+ | + | + | − | NA | NA | − | + | NA | NA |

| 22 | + | + | F+ | NA | + | NA | NA | NA | − | − | + | NA | + |

| 23 | + | + | F+ | − | + | NA | − | − | NA | NA | + | NA | + |

Chromo chromogranin, CK pancytokeratin, F+ focally positive, FISH fluorescence in situ hybridization, NA not available, SMA smooth muscle actin, Synapto synaptophysin

Fig. 3.

ALES demonstrates the membranous reactivity for CD99 (a, 20x) and nuclear positivity for NKX2.2 (b, 20x) characteristic of Ewing sarcoma. However, it is defined by their unique complex epithelial differentiation, with concomitant positivity for pancytokeratin (c, 20x) and p40 (d, 20x)

Molecular Diagnostics

Given the extensive overlap with other head and neck tumors, molecular testing is strongly recommended to confirm an ALES diagnosis. ALES harbors a recurrent t(11;22) EWSR1-FLI1 translocation. This translocation is the most common genetic abnormality identified in Ewing sarcoma and has traditionally been considered pathognomonic for classification in the Ewing family [24]. Either break-apart FISH for EWSR1 and/or FLI1 translocations or reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) can be used clinically to identify this translocation (Table 2). Although it is acceptable to use EWSR1 FISH alone in the appropriate morphologic and immunohistochemical context, caution should be exercised to ensure that other EWSR1-rearranged neoplasms are excluded.

Differential Diagnosis

ALES was initially described as “adamantinoma-like” because its basaloid appearance and cytokeratin positivity created diagnostic confusion with tibial adamantinoma [1, 25]. Although adamantinomas do not pose a significant diagnostic consideration in the head and neck, cases of ALES that arise in this region show both histologic and immunohistochemical overlap with a broad range of other small round blue cell tumors and carcinomas with basaloid features. Indeed, 17 of 23 reported cases initially received different diagnoses, including a wide variety of entities (Table 1) [2, 3, 7–16]. Given the rarity of this tumor, the first hurdle to making this diagnosis is even considering the possibility of ALES. Fortunately, a few key features point to this diagnosis regardless of anatomic site. Histologically, the most helpful finding for identifying ALES is the presence of a basaloid neoplasm with cytologic uniformity despite high-grade histologic features such as necrosis and an elevated mitotic rate. Other microscopic features of ALES, including peripheral nuclear palisading, rosette formation, and abrupt formation of keratin pearls, can also be useful clues to suggest the diagnosis but are neither specific nor uniformly present. Immunohistochemically, concomitant positivity for pancytokeratin, p40, and CD99 is identified by definition in ALES and is relatively specific for this diagnosis. Although synaptophysin is not positive in all cases, tumors that do show co-expression of synaptophysin with diffuse, strong p40 should prompt consideration of ALES, as this pattern is almost never seen in any other head and neck tumor type.

In the sinonasal tract, ALES must be specifically distinguished from a broad range of tumors that also show squamous or neuroendocrine differentiation. NUT carcinoma can be a particularly problematic morphologic mimic because it also displays p40 positivity, abrupt keratinization, nuclear monotony, and even occasional CD99 expression that can overlap with ALES [26, 27]. Fortunately, the NUT1 immunostain is highly sensitive for NUT carcinoma and uniformly negative in ALES [28–30]. Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma demonstrates p40 positivity, keratin pearl formation, peripheral nuclear palisading, and pseudoglandular architecture that can mimic rosette formation but shows significantly more cytologic atypia than ALES. High-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma can also form rosettes and displays peripheral palisading and synaptophysin positivity but it consistently contains more cytologic atypia than ALES and lacks diffuse p40 and CD99 staining. Likewise, olfactory neuroblastoma frequently forms rosettes and pseudorosettes but should lack significant cytokeratin or CD99 expression and generally shows diffuse synaptophysin positivity. SMARCB1-deficient sinonasal carcinoma can raise consideration of ALES through its cellular uniformity despite high-grade features, basaloid cells, and variable positivity for p40 and synaptophysin [31–33]. However, its characteristic plasmacytoid/rhabdoid cells and immunohistochemical loss of SMARCB1 expression are not seen in ALES. Finally, sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma is another poorly differentiated carcinoma that can show highly infiltrative growth, but it lacks diffuse p40 and CD99 positivity and exhibits more marked nuclear pleomorphism.

In the salivary glands, ALES can show overlap with a broad spectrum of tumors that have basaloid or myoepithelial features. Although solid forms of adenoid cystic carcinoma often display a high-grade appearance, infiltrative growth, and irregular glandular spaces that mimic rosettes, focal classic areas of cribriform architecture with distinct ductal and myoepithelial cell populations are usually present to help distinguish it from ALES. Likewise, basal cell adenocarcinoma consists of infiltrative solid nests of basaloid cells that are reminiscent of ALES but is usually a low-grade tumor that lacks necrosis and an elevated mitotic rate. Moreover, while both of these tumors demonstrate p40 positivity, they do so in a biphasic pattern with restriction to basal/myoepithelial cells in contrast to the diffuse expression seen in ALES. A subset of high-grade myoepithelial carcinomas of salivary origin can harbor EWSR1 rearrangements and also demonstrate nuclear uniformity, clear cytoplasm, myxoid to hyalinized matrix, and p40 positivity that can overlap with ALES. While EWSR1 fusion partners have not been established in salivary myoepithelial carcinomas, the FLI1 rearrangements characteristic of ALES have not been noted [34, 35]; strong expression of S100, SMA, and calponin can conversely confirm true myoepithelial differentiation. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT), which more commonly occurs in the abdomen but has rarely been reported in salivary glands and adjacent tissues [36–39], also shares EWSR1 rearrangement, uniform basaloid cells, and prominent fibromyxoid stroma with ALES. However, DSRCT is consistently positive for desmin and WT1, which are not expressed in ALES, and harbors a distinctive WT1 fusion.

Finally, in the thyroid gland, ALES can be mistaken for several other uncommon monomorphic tumors that demonstrate solid growth or high grade features. Poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma can raise consideration of ALES via sheet-like or insular architecture and primitive follicular structures that mimic rosettes, but its expression of TTF1 and PAX8 can confirm thyroid follicular origin. Medullary carcinoma is another common thyroid tumor that also expresses neuroendocrine markers and cytokeratin and tends to show a solid and nested architecture, but more prominent amphophilic cytoplasm, positivity for CEA and calcitonin, and negativity for p40 would rule out ALES. Carcinoma showing thymus-like differentiation (CASTLE) is a high grade basaloid tumor that shares high-molecular weight cytokeratin and p40 expression, occasional overt keratinization, and infiltrative growth with prominent stromal desmoplasia with ALES but can be distinguished by its CD5 and CD117 positivity [40, 41]. Additionally, spindle epithelial tumor with thymus-like differentiation (SETTLE) can also display marked hypercellularity, a primitive basaloid appearance, sclerotic stroma and positivity for both cytokeratin and CD99. However, SETTLE generally has lower grade histology with predominant spindled and glandular architecture that ALES lacks [42, 43].

Treatment and Prognosis

Full understanding of the natural history of ALES is somewhat limited at this point by a paucity of follow-up information, with treatment and outcome data available for just 17 patients at a median duration of 13 months (range 1–156 months; Table 3). Twenty-two of 23 ALES patients (96%) underwent surgical resection, followed by radiation therapy in 12 of 15 cases where details were available (80%) and adjuvant chemotherapy in 15 of 16 cases (94%). Although a variety of chemotherapy regimens were employed, 8 patients (57%) were treated with the Ewing-specific protocol of alternating vincristine/doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide/etoposide (VDC/IE) throughout, 4 patients (29%) were treated with other drug combinations, and 2 patients (14%) had an alternate regimen switched to VDC/IE after a change in diagnosis to ALES.

Table 3.

Treatment and follow-up

| Case | Treatment | Clinical course | Follow-up (months) | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Surgery + XRT + chemo (initially cisplatin, then VDC/IE) | Persistent local disease | NA | AWD |

| 2 | Surgery | No residual disease | 38 | NED |

| 3 | Surgery + XRT + chemo | Local recurrence | 36 | AWD |

| 4 | Surgery | No residual disease | 156 | NED |

| 5 | Surgery + XRT + chemo (VDC/IE) | No residual disease | 1 | NED |

| 6 | Surgery initially. At recurrence, surgery + XRT + chemo (docetaxel, carboplatin, capecitabine, methotrexate) | Local recurrence at 24 months; dural metastases at 46 months | 52 | DWD |

| 7 | XRT + chemo (VDC/IE) | Persistent local disease | 12 | AWD |

| 8 | Surgery + XRT + chemo (ifosfamide/cyclophosphamide/etoposide, then ifosfamide/vincristine/etoposide) | No residual disease | 61 | NED |

| 9 | Surgery, XRT/Chemo pending | No residual disease | 1 | NED |

| 10 | Surgery, XRT/chemo pending | NA | NA | NA |

| 11 | Surgery, XRT/chemo pending | NA | NA | NA |

| 12 | Surgery + chemo (VDC/IE), XRT pending | NA | 2 | NA |

| 13 | Surgery, XRT/chemo pending | No residual disease | 1 | NED |

| 14 | Surgery + XRT + chemo (VDC/IE) | Pancreatic metastasis at 2 months | 24 | NED |

| 15 | Surgery + chemo (VDC/IE), XRT pending | NA | NA | NA |

| 16 | Surgery + chemo (VDC/IE) | No residual disease | 3 | DOC |

| 17 | Surgery + XRT + chemo (doxorubicin) | No residual disease | 13 | NED |

| 18 | Surgery + XRT + chemo (carboplatin/etoposide) | Persistent local disease | 8 | AWD |

| 19 | Surgery + XRT + chemo (VDC/IE) | No residual disease | 19 | NED |

| 20 | Surgery + XRT + chemo (initially carboplatin/paclitaxel then VDC/IE) | No residual disease | 24 | NED |

| 21 | Surgery, XRT/chemo pending | NA | NA | NA |

| 22 | Surgery + XRT + chemo (VDC/IE) | No residual disease | 7 | NED |

| 23 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

AWD alive with disease, Chemo systemic chemotherapy, DOC dead of other causes, DWD dead with disease, NA not available, NED no evidence of disease, VDC/IE alternating vincristine/doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide/etoposide, XRT external-beam radiation therapy

While original reports raised concern that ALES would be a more aggressive variant of Ewing sarcoma due to a lack of tumor necrosis in response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy [1], many patients with head and neck tumors have had good outcomes with surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation. Of the 12 reported cases with more than 6 months of follow-up, 6 patients (50%) experienced persistent, recurrent, or metastatic disease. Outcomes seem to vary across anatomic sites in this cohort, with disease progression in 2 (100%) patients with sinonasal tumors and 2 (67%) patients with soft tissue tumors compared to just 1 patient (33%) with a parotid gland tumor and 1 (25%) patient with a thyroid tumor. This included 2 patients treated with VDC/IE (22%) and 2 patients treated with other regimens (40%). At last follow up, 8 of these patients (66%) had no evidence of disease, 3 patients (25%) were alive with disease, and 1 patient (9%) was dead with disease.

Tumor Classification

There has been persistent controversy regarding whether ALES truly represents a variant of Ewing sarcoma or a carcinoma (e.g., myoepithelial carcinoma) that carries the same translocation. Historically, the EWSR1-FLI1 translocation has been considered pathognomonic for a diagnosis of Ewing sarcoma regardless of histologic features. In the initial description of ALES, Bridge et al. argued that molecular homogeneity supersedes pathologic heterogeneity in Ewing sarcoma, and the complex epithelial differentiation of ALES represents phenotypic drift [1]. Likewise, Folpe et al. noted that ALES falls within a spectrum of variant morphologies that conventionally should be regarded as Ewing sarcoma [5]. Indeed, the nuclear monotony, lobular architecture, rosette formation, and CD99/NKX2.2 positive immunoprofile are quite characteristic of conventional Ewing sarcoma. Following this paradigm, most cases with these pathological, immunohistochemical, and molecular features have been reported using the ALES nomenclature [1, 4–16].

However, since ALES was initially described, there has been increasing recognition that unequivocally distinct tumor types can harbor identical translocations [44]. For example, the ETV6-NTRK3 fusion straddles multiple lineages with involvement in secretory carcinoma, papillary thyroid carcinoma, infantile fibrosarcoma, congenital mesoblastic nephroma, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, and acute myeloid leukemia [45–51]. Even elsewhere in the EWSR1 family, the EWSR1-ATF1 fusion has been implicated in angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma, salivary and odontogenic clear cell carcinoma, clear cell sarcoma, mesothelioma, and intracranial myxoid mesenchymal tumors [52–56]. Indeed, the EWSR1-FLI1 translocation is now one of a shrinking number of gene fusions that remains inextricably linked to a single diagnosis. In this spirit, two cases with identical morphology and immunophenotype to ALES were reported as “carcinoma with Ewing family tumor elements” (CEFTE) [2, 3].

At this point, there is no gold standard to resolve the dichotomy between genotype and phenotype in ALES. Because a specific chemotherapy protocol of alternating VDC/IE is regarded as most effective at treating Ewing sarcoma, and alternate therapeutic regiments are generally used to manage carcinomas [57–60], outcomes data on which regimen is more effective in ALES cases could conceivably inform this distinction. However, limited follow up and confounding differences in tumor behavior across anatomic sites make it impossible to draw conclusions about optimal classification from treatment response at this point. In this review, we chose to adhere to the conventional ALES terminology, believing that consistency in nomenclature between the vast majority of reported cases is more valuable than mirroring standards used in other tumor types. Indeed, we contend that maintaining the more familiar terminology is the best way to promote increased recognition and understanding of this distinctive lesion, potentially facilitating a more informed discussion of its classification and management later on. Regardless of name, there is little doubt that the tumor we have referred to as ALES is a unique, recognizable clinicopathologic entity with specific morphologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular features.

Conclusion

ALES is a rare tumor currently regarded as a variant of Ewing sarcoma that demonstrates well-developed squamous epithelial differentiation. In recent years, ALES has predominantly been reported in the head and neck, where it can show diagnostic overlap with a wide range of small round blue cell tumors and basaloid carcinomas. Some of the most helpful clues to the diagnosis of ALES include cytologic monotony despite high-grade histologic features and co-expression of CD99, pancytokeratin, p40, and synaptophysin; identification of an EWSR1-FLI1 translocation confirms the diagnosis. Improved diagnosis of ALES and documentation of its natural history is essential to resolve ongoing controversy regarding the best classification and management of this distinctive entity.

Funding

None

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bridge JA, Fidler ME, Neff JR, Degenhardt J, Wang M, Walker C, et al. Adamantinoma-like Ewing’s sarcoma: genomic confirmation, phenotypic drift. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23(2):159–165. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199902000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cruz J, Eloy C, Aragues JM, Vinagre J, Sobrinho-Simoes M. Small-cell (basaloid) thyroid carcinoma: a neoplasm with a solid cell nest histogenesis? Int J Surg Pathol. 2011;19(5):620–626. doi: 10.1177/1066896911405320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eloy C, Oliveira M, Vieira J, Teixeira MR, Cruz J, Sobrinho-Simoes M. Carcinoma of the thyroid with ewing family tumor elements and favorable prognosis: report of a second case. Int J Surg Pathol. 2014;22(3):260–265. doi: 10.1177/1066896913486696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barroca H, Souto Moura C, Lopes JM, Lisboa S, Teixeira MR, Damasceno M, et al. PNET with neuroendocrine differentiation of the lung: report of an unusual entity. Int J Surg Pathol. 2014;22(5):427–433. doi: 10.1177/1066896913502227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Folpe AL, Goldblum JR, Rubin BP, Shehata BM, Liu W, Dei Tos AP, et al. Morphologic and immunophenotypic diversity in Ewing family tumors: a study of 66 genetically confirmed cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(8):1025–1033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujii H, Honoki K, Enomoto Y, Kasai T, Kido A, Amano I, et al. Adamantinoma-like Ewing’s sarcoma with EWS-FLI1 fusion gene: a case report. Virchows Arch. 2006;449(5):579–584. doi: 10.1007/s00428-006-0279-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexiev BA, Tumer Y, Bishop JA. Sinonasal adamantinoma-like Ewing sarcoma: a case report. Pathol Res Pract. 2017;213(4):422–426. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2016.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bishop JA, Alaggio R, Zhang L, Seethala RR, Antonescu CR. Adamantinoma-like Ewing family tumors of the head and neck: a pitfall in the differential diagnosis of basaloid and myoepithelial carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39(9):1267–1274. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kikuchi Y, Kishimoto T, Ota S, Kambe M, Yonemori Y, Chazono H, et al. Adamantinoma-like Ewing family tumor of soft tissue associated with the vagus nerve: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37(5):772–779. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31828e5168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lezcano C, Clarke MR, Zhang L, Antonescu CR, Seethala RR. Adamantinoma-like Ewing sarcoma mimicking basal cell adenocarcinoma of the parotid gland: a case report and review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2015;9(2):280–285. doi: 10.1007/s12105-014-0558-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lilo MT, Bishop JA, Olson MT, Ali SZ. Adamantinoma-like Ewing sarcoma of the parotid gland: cytopathologic findings and differential diagnosis. Diagn Cytopathol. 2018;46(3):263–266. doi: 10.1002/dc.23829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinreb I, Goldstein D, Perez-Ordonez B. Primary extraskeletal Ewing family tumor with complex epithelial differentiation: a unique case arising in the lateral neck presenting with Horner syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32(11):1742–1748. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181706252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahadevan P, Ramkumar S, Gangadharan VP. Adamantinoma-Like Ewing’s family tumor of the sino nasal region: a case report and a brief review of literature. Case Rep Pathol. 2019;2019:6. doi: 10.1155/2019/5158182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morlote D, Harada S, Lindeman B, Stevens TM. Adamantinoma-Like Ewing sarcoma of the thyroid: a case report and review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2019;13:618–623. doi: 10.1007/s12105-019-01021-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ongkeko M, Zeck J, deBrito P. Molecular testing uncovers an adamantinoma-like ewing family of tumors in the thyroid: case report and review of literature. AJSP. 2018;23(1):8–12. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rooper LM, Jo VY, Antonescu CR, Nose V, Westra WH, Seethala RR, et al. Adamantinoma-like Ewing sarcoma of the salivary glands: a newly recognized mimicker of basaloid salivary carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43(2):187–194. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fadul J, Bell R, Hoffman LM, Beckerle MC, Engel ME, Lessnick SL. EWS/FLI utilizes NKX2-2 to repress mesenchymal features of Ewing sarcoma. Genes Cancer. 2015;6(3–4):129–143. doi: 10.18632/genesandcancer.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hung YP, Fletcher CD, Hornick JL. Evaluation of NKX2-2 expression in round cell sarcomas and other tumors with EWSR1 rearrangement: imperfect specificity for Ewing sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2016;29(4):370–380. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shibuya R, Matsuyama A, Nakamoto M, Shiba E, Kasai T, Hisaoka M. The combination of CD99 and NKX2.2, a transcriptional target of EWSR1-FLI1, is highly specific for the diagnosis of Ewing sarcoma. Virchows Arch. 2014;465(5):599–605. doi: 10.1007/s00428-014-1627-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collini P, Sampietro G, Bertulli R, Casali PG, Luksch R, Mezzelani A, et al. Cytokeratin immunoreactivity in 41 cases of ES/PNET confirmed by molecular diagnostic studies. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25(2):273–274. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200102000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gu M, Antonescu CR, Guiter G, Huvos AG, Ladanyi M, Zakowski MF. Cytokeratin immunoreactivity in Ewing’s sarcoma: prevalence in 50 cases confirmed by molecular diagnostic studies. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24(3):410–416. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200003000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bishop JA, Montgomery EA, Westra WH. Use of p40 and p63 immunohistochemistry and human papillomavirus testing as ancillary tools for the recognition of head and neck sarcomatoid carcinoma and its distinction from benign and malignant mesenchymal processes. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38(2):257–264. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jo VY, Fletcher CD. p63 immunohistochemical staining is limited in soft tissue tumors. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136(5):762–766. doi: 10.1309/AJCPXNUC7JZSKWEU. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Alava E, Lessnick SL, Sorenson PH. Ewing Sarcoma. In: Fletcher CD, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PC, Mertens F, editors. WHO Classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. pp. 306–309. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hauben E, van den Broek LC, Van Marck E, Hogendoorn PC. Adamantinoma-like Ewing’s sarcoma and Ewing’s-like adamantinoma. The t(11; 22), t(21; 22) status. J Pathol. 2001;195(2):218–221. doi: 10.1002/path.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solomon LW, Magliocca KR, Cohen C, Muller S. Retrospective analysis of nuclear protein in testis (NUT) midline carcinoma in the upper aerodigestive tract and mediastinum. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015;119(2):213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2014.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teo M, Crotty P, O’Sullivan M, French CA, Walshe JM. NUT midline carcinoma in a young woman. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(12):e336–e339. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.7486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agaimy A, Fonseca I, Martins C, Thway K, Barrette R, Harrington KJ, et al. NUT carcinoma of the salivary glands: clinicopathologic and molecular analysis of 3 cases and a survey of NUT expression in salivary gland carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42(7):877–884. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bishop JA, Westra WH. NUT midline carcinomas of the sinonasal tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36(8):1216–1221. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318254ce54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haack H, Johnson LA, Fry CJ, Crosby K, Polakiewicz RD, Stelow EB, et al. Diagnosis of NUT midline carcinoma using a NUT-specific monoclonal antibody. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(7):984–991. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318198d666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agaimy A, Hartmann A, Antonescu CR, Chiosea SI, El-Mofty SK, Geddert H, et al. SMARCB1 (INI-1)-deficient sinonasal carcinoma: a series of 39 cases expanding the morphologic and clinicopathologic spectrum of a recently described entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41(4):458–471. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agaimy A, Koch M, Lell M, Semrau S, Dudek W, Wachter DL, et al. SMARCB1(INI1)-deficient sinonasal basaloid carcinoma: a novel member of the expanding family of SMARCB1-deficient neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38(9):1274–1281. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bishop JA, Antonescu CR, Westra WH. SMARCB1 (INI-1)-deficient carcinomas of the sinonasal tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38(9):1282–1289. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dalin MG, Katabi N, Persson M, Lee KW, Makarov V, Desrichard A, et al. Multi-dimensional genomic analysis of myoepithelial carcinoma identifies prevalent oncogenic gene fusions. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1197. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01178-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skalova A, Weinreb I, Hyrcza M, Simpson RH, Laco J, Agaimy A, et al. Clear cell myoepithelial carcinoma of salivary glands showing EWSR1 rearrangement: molecular analysis of 94 salivary gland carcinomas with prominent clear cell component. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39(3):338–348. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Faras F, Abo-Alhassan F, Hussain AH, Sebire NJ, Al-Terki AE. Primary desmoplastic small round cell tumor of upper cervical lymph nodes. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015;120(1):e4–e10. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mihok NA, Cha I. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor presenting as a neck mass: a case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 2001;25(1):68–72. doi: 10.1002/dc.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pang B, Leong CC, Salto-Tellez M, Petersson F. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor of major salivary glands: report of 1 case and a review of the literature. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2011;19(1):70–75. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e3181eec73c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolf AN, Ladanyi M, Paull G, Blaugrund JE, Westra WH. The expanding clinical spectrum of desmoplastic small round-cell tumor: a report of two cases with molecular confirmation. Hum Pathol. 1999;30(4):430–435. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(99)90119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dorfman DM, Shahsafaei A, Miyauchi A. Intrathyroidal epithelial thymoma (ITET)/carcinoma showing thymus-like differentiation (CASTLE) exhibits CD5 immunoreactivity: new evidence for thymic differentiation. Histopathology. 1998;32(2):104–109. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1998.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kakudo K, Bai Y, Ozaki T, Homma K, Ito Y, Miyauchi A. Intrathyroid epithelial thymoma (ITET) and carcinoma showing thymus-like differentiation (CASTLE): cD5-positive neoplasms mimicking squamous cell carcinoma of the thyroid. Histol Histopathol. 2013;28(5):543–556. doi: 10.14670/HH-28.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheuk W, Jacobson AA, Chan JK. Spindle epithelial tumor with thymus-like differentiation (SETTLE): a distinctive malignant thyroid neoplasm with significant metastatic potential. Mod Pathol. 2000;13(10):1150–1155. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Folpe AL, Lloyd RV, Bacchi CE, Rosai J. Spindle epithelial tumor with thymus-like differentiation: a morphologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 11 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(8):1179–1186. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31819e61c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Antonescu CR, Dal Cin P. Promiscuous genes involved in recurrent chromosomal translocations in soft tissue tumours. Pathology. 2014;46(2):105–112. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0000000000000049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alassiri AH, Ali RH, Shen Y, Lum A, Strahlendorf C, Deyell R, et al. ETV6-NTRK3 is expressed in a subset of ALK-negative inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40(8):1051–1061. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Knezevich SR, McFadden DE, Tao W, Lim JF, Sorensen PH. A novel ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion in congenital fibrosarcoma. Nat Genet. 1998;18(2):184–187. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kralik JM, Kranewitter W, Boesmueller H, Marschon R, Tschurtschenthaler G, Rumpold H, et al. Characterization of a newly identified ETV6-NTRK3 fusion transcript in acute myeloid leukemia. Diagn Pathol. 2011;6:19. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-6-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leeman-Neill RJ, Kelly LM, Liu P, Brenner AV, Little MP, Bogdanova TI, et al. ETV6-NTRK3 is a common chromosomal rearrangement in radiation-associated thyroid cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(6):799–807. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rubin BP, Chen CJ, Morgan TW, Xiao S, Grier HE, Kozakewich HP, et al. Congenital mesoblastic nephroma t(12;15) is associated with ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion: cytogenetic and molecular relationship to congenital (infantile) fibrosarcoma. Am J Pathol. 1998;153(5):1451–1458. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65732-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Skalova A, Vanecek T, Sima R, Laco J, Weinreb I, Perez-Ordonez B, et al. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands, containing the ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene: a hitherto undescribed salivary gland tumor entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(5):599–608. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181d9efcc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tognon C, Knezevich SR, Huntsman D, Roskelley CD, Melnyk N, Mathers JA, et al. Expression of the ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion as a primary event in human secretory breast carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2002;2(5):367–376. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Antonescu CR, Katabi N, Zhang L, Sung YS, Seethala RR, Jordan RC, et al. EWSR1-ATF1 fusion is a novel and consistent finding in hyalinizing clear-cell carcinoma of salivary gland. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2011;50(7):559–570. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Desmeules P, Joubert P, Zhang L, Al-Ahmadie HA, Fletcher CD, Vakiani E, et al. A subset of malignant mesotheliomas in young adults are associated with recurrent EWSR1/FUS-ATF1 fusions. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41(7):980–988. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hallor KH, Mertens F, Jin Y, Meis-Kindblom JM, Kindblom LG, Behrendtz M, et al. Fusion of the EWSR1 and ATF1 genes without expression of the MITF-M transcript in angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2005;44(1):97–102. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kao YC, Sung YS, Zhang L, Chen CL, Vaiyapuri S, Rosenblum MK, et al. EWSR1 fusions With CREB family transcription factors define a novel myxoid mesenchymal tumor with predilection for intracranial location. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41(4):482–490. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zucman J, Delattre O, Desmaze C, Epstein AL, Stenman G, Speleman F, et al. EWS and ATF-1 gene fusion induced by t(12;22) translocation in malignant melanoma of soft parts. Nat Genet. 1993;4(4):341–345. doi: 10.1038/ng0893-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gradoni P, Giordano D, Oretti G, Fantoni M, Barone A, La Cava S, et al. Clinical outcomes of rhabdomyosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma of the head and neck in children. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2011;38(4):480–486. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grier HE, Krailo MD, Tarbell NJ, Link MP, Fryer CJ, Pritchard DJ, et al. Addition of ifosfamide and etoposide to standard chemotherapy for Ewing’s sarcoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumor of bone. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(8):694–701. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang M, Lucas K. Current therapeutic approaches in metastatic and recurrent ewing sarcoma. Sarcoma. 2011;2011:863210. doi: 10.1155/2011/863210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rodriguez-Galindo C, Spunt SL, Pappo AS. Treatment of Ewing sarcoma family of tumors: current status and outlook for the future. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2003;40(5):276–287. doi: 10.1002/mpo.10240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]