Abstract

Background

Falls represent a global health issue among older adults and cause a considerable burden on medical systems. In this study, a fall-risk assessment profile was developed for community-dwelling older adults.

Method

The data of survey participants aged > 65 years were obtained from three rounds (2005, 2009, and 2013) of the National Health Interview Survey in Taiwan. In total, 8356 older participants were included in this study. Logistic regression analyses were used to determine potential predictors associated with falls. The regression coefficients of the predictors in the final model were translated into scores (by multiplying by 5) and then summed to obtain a total risk-score for falls. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to evaluate the discriminative performance of the risk assessment profile.

Result

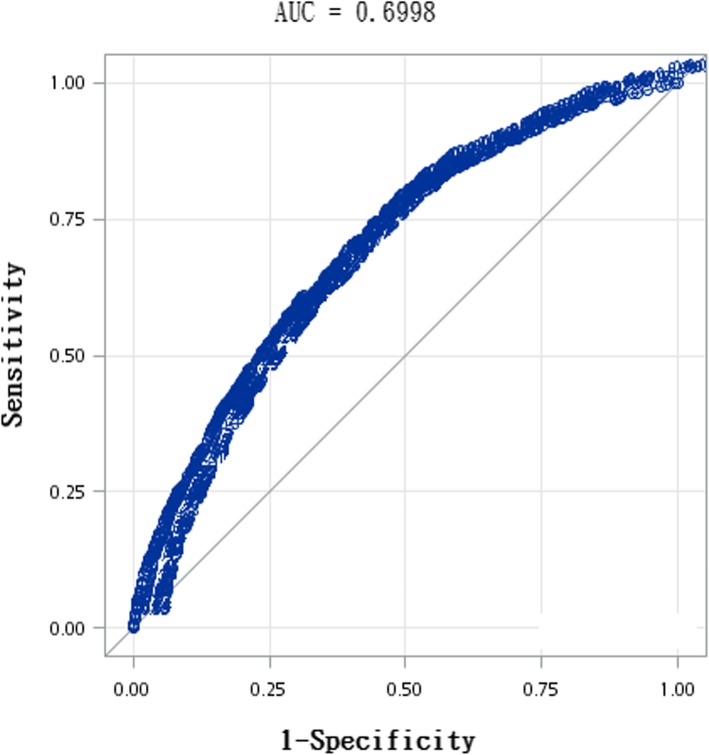

Self-reported falls within 1 year accounted for 19.1% of the total falls. The predictors that were included in the risk profile according to the logistic regression analysis results were as follows: female sex (adjusted odds ratio = 1.57; risk-score = 2), living alone (adjusted odds ratio = 1.56; risk-score = 2), urinary incontinence (adjusted odds ratio = 1.36; risk-score = 2), perceived unhealthiness (adjusted odds ratio = 1.32; risk-score = 1), perceived pain (adjusted odds ratio = 1.51; risk-score = 2), hospital admission in the past year (adjusted odds ratio = 2.42; risk-score = 4), low activity of daily living (ADL) scores (adjusted odds ratio = 1.29; risk-score = 1), and low mobility function scores (adjusted odds ratio = 1.68; risk-score = 3). At a total risk-score cutoff point of 6 (range 0–17), the model predicted falls with a sensitivity and specificity of 75.16 and 52.75%, respectively (area under the ROC curve = 0.70).

Conclusion

The fall-risk assessment profile comprising eight predictors—female sex, living alone, incontinence, perceived unhealthiness, perceived pain, hospital admission in the past year, low ADL scores, and low mobility function scores—may serve as an assessment tool for identification of older adults with a high risk of falling, and assessment results can be used to facilitate community-based intervention.

Keywords: Older, Fall, National Health Interview Survey, Risk assessment profile

Background

Falls represent a major cause of disability and death, particularly in the older population, and contribute to serious public health problems worldwide [1]. Age is a well-known risk factor for falls. Age-related injuries resulting from falls are expected to increase considerably due to an increase in the proportion of older-aged individuals in the overall population. The incidence of falls varies worldwide [2–4]. Approximately one quarter of adults aged > 60 year-old experience at least one fall, and one out of five falls results in serious injury associated with a substantial burden not only on the older adults but also on their families and society; moreover, fall-related injuries are associated with high medical expenses and health care demands [5–7]. The consequences of falls are serious in the older adult population [8].

Falls in older adults can be prevented. A history of falls is associated with a high risk of recurrent falling [9, 10]. The prevention of falls has become a crucial research area because of the severe potential consequences of falling. Identification of potential factors associated with falls may facilitate development of an effective fall-prevention program. Several studies have reported interventions that reduced the risk of falling [11–13]. Over many years, epidemiological data have been collected to identify fall-related risk factors, and fall-prevention programs have been proposed and evaluated [5, 14, 15]. In a report published by the World Health Organization in 2008, the main risk factors for falls were categorized as follows: biological risk factors (e.g., age), behavioral factors (e.g., alcohol use), environmental factors (e.g., home hazards), and socioeconomic factors (e.g., income) [1]. However, the risk profiles of falls in older adults may vary across countries and cultures [16]. A comprehensive study for the development of a risk profile to predict recurrent falls among older individuals was proposed in 2006 [17], but this risk profile was for community-dwelling older adults in the Netherlands. An appropriate risk assessment instrument for Asian older adults needs to be developed.

In this study, we developed a risk assessment profile for falls in older adults by using a national database, the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) in Taiwan. The predictors of the risk of falling in older patients were investigated, and a total risk score was calculated to identify older adults at a high risk of falling.

Methods

Data source

The NHIS is a large-scale, cross-sectional, and face-to-face survey that is conducted once every 4 years by the Health Promotion Administration, National Health Research Institutes, Food and Drug Administration, and Ministry of Health and Welfare of Taiwan. The participants in the NHIS were sampled using a multistage probability proportional to sample size technique. Survey questionnaires were prepared for three age groups, namely, ≥65 years, 12–64 years, and ≤ 11 years. In this study, the participants aged ≥65 years were obtained from the NHIS 2005, 2009, and 2013 databases, respectively. This study was approved by the Taipei Medical University-Joint Institution Review Board (TMU-JIRB N201612015), and the data were provided by the Health and Welfare Data Science Center.

The participants recalled their fall experiences in the past year, including falls caused by slipping, walking, dizziness, sitting, standing, or lying down. Several aspects of physical and social functioning were also assessed in the NHIS, and the potential predictors of the risk of falling were classified into four categories: demographic characteristics, health status, activity or mobility, and life style. In total, 34 potential predictors listed in the NHIS database were selected for developing the risk profile of falling for the older participants.

The demographic characteristics included age (> 75 years or ≤ 75 years), sex, living in a highly urbanized area (the first of seven clusters defined by Liu et al. [18], living alone, marital status, working status, and income. The monthly income of the entire family was categorized as < 30,000 New Taiwan dollars (NTD) (equal to 1000 USD) or ≥ 30,000 NTD. The participants were also asked to specify their highest completed educational level, and a high education level was defined as ≥10 years of education. The following 19 variables were identified under the health status category: diabetes, hyperlipidemia, asthma, cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, psychological disease, epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease, dementia, osteoarthritis, urinary incontinence, hypertension, visual impairment, hearing impairment, paralysis of limbs, poor self-reported health status, pain (including pain in the arms, hips, knees, chest, and back), hospital admission in the past year, and body mass index (BMI). BMI was calculated using body weight and height, and participants with BMI ≤24 kg/m2 and those with BMI > 24 kg/m2 were compared.

A poor mobility status was defined as a score ≥ 1 on one or more mobility tests. The functional limitations of the participants were assessed based on activity of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activity of daily living (IADL) scores, including scores for core daily personal self-care tasks (e.g., eating). Low ADL and IADL scores reflected difficulty performing more than two activities. Four life style variables, namely regular exercise, alcohol use, current smoking status, and betel nut chewing, were evaluated.

Statistical analysis

Fall-related risk factors were identified using a multistep process. First, prevalence, percentage of missing values, and univariate logistic regression were calculated for each potential variable. The Spearman correlations between the variables were also calculated. Variables were excluded if their prevalence was less than 10%, the number of missing values exceeded 10%, or p > 0.2 in univariate logistic regression. Additionally, if two variables were highly correlated (Spearman correlation 0.4), the variable that was more easily measured was retained. After excluding the non-eligible variables, multivariable logistic regression and backward elimination with a stay-significance level of 0.2 were applied to identify the potential predictors to be included in the risk profiles of falling in the older adults. The modified falling risk profile was investigated and the weight (score) of each predictor was defined as the regression coefficient multiplied by 5 and rounded off to the nearest integer. A total risk-score was calculated for each participant. The evaluation values used in this study were negative predictive value (NPV), positive predictive value (PPV), sensitivity, and specificity. PPV indicated the probability of falling among the participants who were in the high-risk group, and NPV indicated the probability of not falling among the participants who were in the low-risk group. Sensitivity represented the probability of correctly identifying the older participants who experienced falls (fallers) as having at least one fall, and specificity was the probability of correctly identifying the older patients who did not experience falls (nonfallers). The diagnostic value was evaluated based on the receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve, and the optimal cutoff point value was defined as the point corresponding with the maximum summed sensitivity and specificity. The analyses were performed using SAS software, Version 9.4 in the SAS system for Windows.

Results

Demographic characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the participants are listed in Table 1. From three survey rounds, 8356 participants aged ≥65 years were included in this study, and of these, 1589 (19%) had at least one fall event in the previous year. Overall, 22.1% female and 15.8% male participants reported at least one fall in the previous year. The percentage of the participants who experienced at least one fall in the past year was higher among those aged > 75 years than among those aged 65–75 years. In addition, participants with chronic diseases, such as diabetes, hyperglycemia, asthma, and cardiovascular disease, had a higher percentage of experiencing at least one fall in the past year than did those who did not have chronic diseases. The participants with low ADL scores or activity functions exhibited a > 2-times higher risk of falling than the participants with high ADL scores or activity functions. Moreover, the participants who did not smoke, or consume alcohol had a higher percentage of falls in the past year than those with these habits. However, the participants who chewed betel nut had a higher percentage of falls in the past year than those without these habits.

Table 1.

Prevalence, univariate odds ratios (ORs), and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for potential predictors of falling

| Variable | Number | Missing rate(%) | Prevalence | OR | 95% CI of OR (p-value) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| faller | Not faller | |||||

| Total | 1598 | 6758 | 19.1 | |||

| Gender | 0 | |||||

| Male | 617 | 3295 | 15.8 | Reference | – | |

| Female | 981 | 3463 | 22.1 | 1.51* | 1.35–1.69(< 0.01) | |

| Age | 0 | |||||

| 65–75 years old | 792 | 3917 | 16.8 | Reference | – | |

| ≥ 75 years old | 806 | 2841 | 22.1 | 1.40* | 1.26–1.57(< 0.01) | |

| Area | 0.28 | |||||

| Non-urbanized | 1255 | 5241 | 19.3 | Reference | – | |

| Urbanized | 337 | 1500 | 18.3 | 0.94 | 0.82–1.07 (0.34) | |

| Education | 0.78 | |||||

| Not high | 1434 | 5662 | 20.2 | Reference | – | |

| High | 154 | 1041 | 12.9 | 0.58* | 0.49–0.70(< 0.01) | |

| Living alone | 0 | |||||

| No | 1374 | 6019 | 18.6 | Reference | – | |

| Yes | 224 | 739 | 23.3 | 1.33* | 1.13–1.56(< 0.01) | |

| Marital status | 0 | |||||

| Married | 886 | 4320 | 17.0 | Reference | – | |

| Single or others | 712 | 2438 | 22.6 | 1.43* | 1.28–1.59(< 0.01) | |

| Working status | 0 | |||||

| Working | 174 | 1069 | 14.0 | Reference | – | |

| Retired or others | 1424 | 5689 | 20.0 | 1.53* | 1.29–1.81(< 0.01) | |

| Income | 4.61 | |||||

| ≥ 30,000 | 732 | 3307 | 18.1 | Reference | – | |

| < 30,000 | 799 | 3133 | 20.3 | 1.15* | 1.03–1.29 (0.01) | |

| Diabetes | 0.14 | |||||

| No | 1203 | 5462 | 18.0 | Reference | – | |

| Yes | 391 | 1288 | 23.3 | 1.38* | 1.21–1.57(< 0.01) | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.40 | |||||

| No | 1148 | 5095 | 18.4 | Reference | – | |

| Yes | 415 | 1581 | 20.8 | 1.17* | 1.03–1.32 (0.02) | |

| Asthma | 0 | |||||

| No | 1490 | 6396 | 18.9 | Reference | – | |

| Yes | 108 | 362 | 23.0 | 1.28* | 1.03–1.60 (0.03) | |

| Cardiovascular disease | 0 | |||||

| No | 1228 | 5633 | 17.9 | Reference | – | |

| Yes | 370 | 1125 | 24.7 | 1.51* | 1.32–1.72(< 0.01) | |

| Osteoporosis | 0.22 | |||||

| No | 1108 | 5298 | 17.3 | Reference | – | |

| Yes | 486 | 1446 | 25.2 | 1.61* | 1.42–1.82(< 0.01) | |

| Psycho disease | 0 | |||||

| No | 1542 | 6582 | 19.0 | Reference | – | |

| Yes | 56 | 176 | 24.1 | 1.36* | 1.002–1.85 (0.04) | |

| Epilepsy | 0 | |||||

| No | 1589 | 6744 | 19.1 | Reference | – | |

| Yes | 9 | 14 | 39.1 | 2.73* | 1.18–6.31 (0.02) | |

| Parkinson’s disease | 0.13 | |||||

| No | 1539 | 6644 | 18.8 | Reference | – | |

| Yes | 52 | 110 | 32.1 | 2.04* | 1.46–2.85(< 0.01) | |

| Dementia | 0 | |||||

| Noa | 1482 | 6550 | 18.5 | Reference | – | |

| Yes | 116 | 208 | 35.8 | 2.46* | 1.95–3.11(< 0.01) | |

| Osteoarthritis | 0 | |||||

| Noa | 1307 | 5921 | 18.1 | Reference | – | |

| Yes | 291 | 837 | 25.8 | 1.58* | 1.36–1.83(< 0.01) | |

| Urinary incontinence | 0.34 | |||||

| No | 1068 | 5321 | 16.7 | Reference | – | |

| Yes | 523 | 1416 | 27.0 | 1.84* | 1.63–2.08(< 0.01) | |

| Hypertension | 0.12 | |||||

| No | 739 | 3561 | 17.2 | Reference | – | |

| Yes | 855 | 3191 | 21.1 | 1.29* | 1.16–1.44(< 0.01) | |

| Visual impairment | 0.11 | |||||

| No | 277 | 1288 | 17.7 | Reference | – | |

| Yes | 1321 | 5461 | 19.5 | 1.13 | 0.98–1.30 (0.11) | |

| Hearing impairment | 0.04 | |||||

| No | 1192 | 5486 | 17.8 | Reference | – | |

| Yes | 406 | 1269 | 24.2 | 1.47* | 1.30–1.67(< 0.01) | |

| Paralysis of limbs | 0.69 | |||||

| No | 1381 | 6183 | 18.3 | Reference | – | |

| Yes | 203 | 531 | 27.7 | 1.71* | 1.44–2.03(< 0.01) | |

| Self-report health status | 9.16 | |||||

| Health | 488 | 3248 | 13.1 | Reference | – | |

| poor | 896 | 2959 | 23.2 | 2.02* | 1.79–2.28(< 0.01) | |

| Pain | 2.42 | |||||

| No | 519 | 3386 | 13.3 | Reference | – | |

| Yes | 1053 | 3196 | 24.8 | 2.15* | 1.92–2.41(< 0.01) | |

| Hospital visit in the past year | 0 | |||||

| No | 940 | 5337 | 15.0 | Reference | – | |

| Yes | 658 | 1421 | 31.6 | 2.63* | 2.34–2.95(< 0.01) | |

| BMI | 9.72 | |||||

| > 24 | 696 | 2848 | 19.6 | Reference | – | |

| ≤ 24 | 724 | 3276 | 18.1 | 0.90 | 0.81–1.02 (0.09) | |

| ADLs | 0.08 | |||||

| < 3 activities | 1299 | 6135 | 17.5 | Reference | – | |

| ≥ 3 activities | 299 | 616 | 32.7 | 2.29* | 1.97–2.67(< 0.01) | |

| IADLs | 0.3 | |||||

| Good | 833 | 4767 | 14.9 | Reference | – | |

| Poor | 761 | 1970 | 27.9 | 2.21* | 1.98–2.47(< 0.01) | |

| Mobility | 0.35 | |||||

| Good | 433 | 3414 | 11.3 | Reference | – | |

| Poor | 1161 | 3319 | 25.9 | 2.76* | 2.45–3.11(< 0.01) | |

| Regular exercise | 3.47 | |||||

| No | 1445 | 6050 | 19.3 | Reference | – | |

| Yes | 82 | 489 | 14.4 | 0.70* | 0.55–0.89(< 0.01) | |

| Alcohol consumer | 0.37 | |||||

| No | 1434 | 5767 | 19.9 | Reference | – | |

| Yes | 157 | 967 | 14.0 | 0.65* | 0.55–0.78(< 0.01) | |

| Current smoker | 0 | |||||

| No | 1439 | 5863 | 19.7 | Reference | – | |

| Yes | 159 | 895 | 15.1 | 0.72* | 0.61–0.86(< 0.01) | |

| Betel nut chewing | 0 | |||||

| No | 1536 | 6536 | 19.0 | Reference | – | |

| Yes | 62 | 222 | 21.8 | 1.19 | 0.89–1.58 (0.24) | |

The odd of falling in the female participants was 1.51 times higher than that in the male participants (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.35–1.69). The odd of falling in the participants aged > 75 years was 1.40 times higher than that in the participants aged 65–75 years (95% CI, 1.26–1.57).

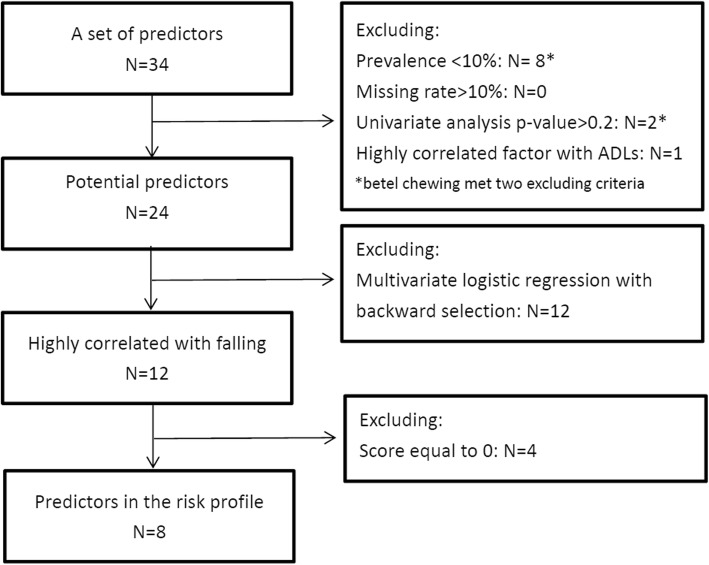

Potential predictor selection

The flow chart illustrating the selection of the potential factors is presented in Fig. 1. The prevalence of the following eight factors was less than 10%: asthma, psychological disease, epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease, dementia, paralysis of limbs, regular exercise, and betel nut chewing. The percentages of missing values for each factor are indicated in the sixth column of Table 1. The proportion did not exceed 10% for any factor. In addition, the odds ratios and corresponding p-values from the univariate analysis for each potential factor are denoted in the fifth column of Table 1. Two factors, namely living in urban areas and betel nut chewing, were nonsignificant (p > 0.2). Moreover, the ADL score, which was relatively easy to measure, was significant and highly correlated with the IADL score. Therefore, the ADL score was retained as a factor, and the IADL score was excluded. After applying the exclusion criteria, 24 potential predictors remained in the risk profile of falling.

Fig. 1.

The study flow chart. N: number of risk factor

All 24 eligible factors were assessed in the multivariable regression model by using backward elimination, and the 12 factors selected for the final risk profile were age, sex, living alone, education, work status, diabetes, urinary incontinence, self-reported health status, pain, hospital admission in past year, ADL score, and mobility. The results are displayed in Table 2, and four of the factors, namely age, education, working status, and diabetes prevalence, exhibited a score of 0 and p > 0.05. The older participants who had been admitted to the hospital in the past year exhibited a high risk-score (4) in the risk profile of falling. The participants with low mobility scores exhibited a risk-score of 3. Some of the participants who were women, were living alone, had urinary incontinence, or experienced pain exhibited risk-scores of 2. The older participants with poor perceived health status or low ADL score, exhibited risk-scores of 1.

Table 2.

Risk profile of falling among older

| Predictors | Regression coefficient | Odds Ratio | P-value | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | −2.73 | |||

| Age (≥75) | 0.08 | 1.08 | 0.28 | 0 |

| Female | 0.45 | 1.57* | 0.02 | 2 |

| Live alone | 0.45 | 1.56* | < 0.01 | 2 |

| High education | −0.09 | 0.91 | 0.59 | 0 |

| Retired | −0.03 | 0.98 | 0.86 | 0 |

| diabetes | 0.003 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0 |

| Involuntary loss of urine | 0.30 | 1.36* | < 0.01 | 2 |

| Self-perceived Health (poor) | 0.28 | 1.32* | 0.02 | 1 |

| Pain | 0.41 | 1.51* | < 0.01 | 2 |

| Hospital admission in the past year | 0.88 | 2.42* | < 0.01 | 4 |

| ADLs (poor) | 0.25 | 1.29* | 0.03 | 1 |

| Mobility (poor) | 0.52 | 1.68* | < 0.01 | 3 |

*: p-value < 0.05

The ROC curve of the risk of falling profile in the older participants is shown in Fig. 2, and the area under the ROC curve (AUROC) is 0.70. The NPV, PPV, sensitivity, and specificity assessed for different cutoff values in the total risk-score are shown in Table 3. The NPV, PPV, sensitivity, and specificity at a cutoff point of 1 were 20.42, 93.46, 96.81, and 10.79%, respectively. The sensitivity was moderate and the specificity was low at a relatively low cutoff. When the cutoff score increased, the sensitivity decreased and the specificity increased. The maximum summation of sensitivity and specificity was reached at a score of 6 (scores of 0–5 versus ≥6), and its corresponding PPV, NPV, sensitivity and specificity were 27.33, 89.98, 75.16, and 52.75%. At a cutoff score of 6, 24.84% of the fallers were not included in the high-risk group, and 47.25% of the nonfallers were included in the high-risk group. With a cutoff score of 11 (score of 0–10 versus ≥11), the sensitivity was low (26.2%) and the specificity was high (90%).

Fig. 2.

ROC curve

Table 3.

Sensitivity and specificity at different cut-off points in the total risk score

| Cut-off in the total risk score | A(n) | B(n) | C(n) | D(n) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Σ% | PV+(%) | PV-(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 vs. ≥1 | 1547 | 6029 | 51 | 729 | 96.8 | 10.8 | 107 | 20.4 | 93.5 |

| 0–1 vs. ≥2 | 1522 | 5773 | 76 | 985 | 95.2 | 14.6 | 110 | 20.9 | 92.8 |

| 0–2 vs. ≥3 | 1450 | 4923 | 148 | 1835 | 90.7 | 27.2 | 118 | 22.8 | 92.5 |

| 0–3 vs. ≥4 | 1401 | 4367 | 197 | 2391 | 87.7 | 35.4 | 123 | 24.3 | 92.4 |

| 0–4 vs. ≥5 | 1315 | 3808 | 283 | 2950 | 82.3 | 43.7 | 126 | 25.7 | 91.2 |

| 0–5 vs. ≥6 | 1201 | 3193 | 397 | 3565 | 75.2 | 52.8 | 128a | 27.3 | 90.0 |

| 0–6 vs. ≥7 | 1063 | 2621 | 535 | 4137 | 66.5 | 61.2 | 128a | 28.9 | 88.5 |

| 0–7 vs. ≥8 | 911 | 2091 | 687 | 4667 | 57.0 | 69.1 | 126 | 30.3 | 87.2 |

| 0–8 vs. ≥9 | 720 | 1427 | 878 | 5331 | 45.1 | 78.9 | 124 | 33.5 | 85.9 |

| 0–9 vs. ≥10 | 604 | 1099 | 994 | 5659 | 37.8 | 83.7 | 122 | 35.5 | 85.1 |

| 0–10 vs. ≥11 | 419 | 641 | 1179 | 6117 | 26.2 | 90.5 | 117 | 39.5 | 83.8 |

| 0–11 vs. ≥12 | 335 | 470 | 1263 | 6288 | 21.0 | 93.0 | 114 | 41.6 | 83.3 |

| 0–12 vs. ≥13 | 189 | 208 | 1409 | 6550 | 11.8 | 96.9 | 109 | 47.6 | 82.3 |

| 0–13 vs. ≥14 | 136 | 142 | 1462 | 6616 | 8.5 | 97.9 | 106 | 48.9 | 81.9 |

| 0–14 vs. ≥15 | 43 | 39 | 1555 | 6719 | 2.7 | 99.4 | 102 | 52.4 | 81.2 |

| 0–15 vs. ≥16 | 12 | 10 | 1586 | 6748 | 0.8 | 99.9 | 101 | 54.5 | 81.0 |

| 0–16 vs. ≥17 | 4 | 3 | 1594 | 6755 | 0.3 | 100.0 | 100 | 57.1 | 80.9 |

A, number of participants who were assigned to the high-risk group and who were fallers; B, number of participants who were assigned to the high risk group and who were not fallers; C, number of participants who were assigned to the low-risk group and who were fallers; D, number of participants who were assigned to the low-risk group and who were not fallers; Σ Sum of sensitivity (A/(A + C))and specificity (D/(B + D)); PV+: Positive predictive value (A/(A + B)); PV- Negative predictive value (D/(C + D))

aMaximal sum of sensitivity and specificity

Discussion

The series of nationwide surveys revealed that the risk of falling in the older participants with at least one fall could be predicted using a risk profile based on eight predictors. The participants who were women, lived alone, experienced urinary incontinence, self-reported poor health status, experienced pain, had undergone hospital admission in the past year, had low ADL scores, or had low mobility scores exhibited a high risk of falling. The AUROC was 0.7 for the proposed risk assessment instrument. The corresponding sensitivity and specificity varied with cutoff scores. At a cutoff score of 6, the summation of sensitivity (75.16%) and specificity (52.75%) was maximal.

Our results revealed that the risk of falling differed in the male and female participants. The reason for the higher risk in the female participants than in the male participants may have been the loss of bone mineral density associated with menopause [19]. However, a previous study showed that after the first occurrence of a fall, sex did not significantly affect the risk of recurrent falls; hence, sex was not included in the risk profile for recurrent falls [17]. Living alone has been identified as a significant risk factor; several studies have shown that older adults living alone are > 2 times more likely to experience a fall than those who do not live alone [20–22]. In this study, living alone was a significant risk factor for falling. One health risk, urinary incontinence, was observed in more than one-third of older adults who lived in communities, had long stay durations in institutions, or had undergone hospitalization. Our study indicated that urinary incontinence was a risk factor for falls, and several cross-sectional epidemiological studies have shown a significant association between the occurrence of falls and urinary incontinence [23, 24]. Chronic pain is strongly associated with falls, and pain is common in older adults (up to 76%) [25, 26]. In our study, general pain status (for all pain locations) was assessed, and it was a risk factor for falls with a score of 2 among the older participants. Pain has been reported to be a risk factor for recurrent falling; therefore, an older patient who experiences pain requires close attention [27].

In our study, low ADL scores and low mobility were associated with high risk of falling. Similar results have been previously reported [28, 29]. These results show that facilitating the maintenance of healthy ADLs in older adults is necessary, but some mobility behaviors may be associated with the risk of falling [30]. Home safety modifications have been suggested to reduce the risk of falling during the performance of ADLs [31, 32]. Some studies have investigated the risk of falling in hospitalized patients [33, 34]. Researchers have also examined hospital admissions that resulted in falls [35]. In our study, the hospital admission was a significant risk factor for falling in the proposed risk assessment instrument.

All the significant risk factors from our study have been presented separately in previous studies. In this study, these risk factors were evaluated simultaneously. A modified falling risk assessment instrument was proposed; health providers can use this instrument to easily assess older adults’ risk of falling. In this study, the total risk-score was calculated, facilitating identification of patients with high risk of falling. In practice, health providers can refer high-risk patients to relevant intervention programs to prevent falls.

This study exhibited several strengths. The risk profile was developed based on a large sample, which was selected by an experienced survey group through a standard interview process. The population-based sample used in this study was representative of the population of older adults in Taiwan.

A limitation in this study was that some data, such as physical activity volume, were self-reported. This may have reduced the accuracy of data and thus resulted in recall bias. The fall experience was recalled retrospectively, and this may result in recall bias. Another limitation was that impact and severity of falls were not evaluated in this study. Moreover, our predicting model did not include a history of falls, which is known as a strong predictors of falls.

Conclusion

Based on the data obtained from three rounds of the NHIS in Taiwan, an instrument for the assessment of the risk of falling in older adults (in Taiwan) was developed. A friendly tool was proposed to identify older adults with a high risk of falls. Identification of these individuals may reduce the number of injuries and fractures resulting from falls.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Executive Yuan, Taiwan (Grant number: E1030909-105) and a grant from Yuan’s General Hospital (Grant number: TMU106YGH-TMU-07). The data sources used in the present study were provided by the Health and Welfare Data Science Center, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan.

Abbreviations

- ADL

Activity of daily living

- AUROC

Area under the ROC curve

- BMI

Body mass index

- CI

Confidence interval

- IADL

Instrumental activity of daily living

- NHIS

National Health Interview Survey

- NPV

Negative predictive value

- PPV

Positive predictive value

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

Authors’ contributions

HY L and PL C contributed to conception and design of the study. HP M and JR O contributed to data analysis and interpretation of data. HP M, HY L and PL C drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partly supported by a grant from the Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Executive Yuan, Taiwan (Grant number: E1030909–105) (PL C) and a grant from Yuan’s General Hospital (Grant number: TMU106YGH-TMU-07) (HP M) for data collection and analysis.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Health Promotion Administration, National Health Research Institutes, Food and Drug Administration, and Ministry of Health and Welfare of Taiwan but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available with permission of Health Promotion Administration, National Health Research Institutes, Food and Drug Administration, and Ministry of Health and Welfare of Taiwan.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Taipei Medical University-Joint Institution Review Board (TMU-JIRB N201612015).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ping-Ling Chen and Hsiao-Yu Lin contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Ping-Ling Chen, Email: plchen@tmu.edu.tw.

Hsiao-Yu Lin, Email: ablin@tmu.edu.tw.

References

- 1.Organization, T.W.H . Global tuberculosis control: surveillance, planning, financing. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kang L, et al. Timed up and go test can predict recurrent falls: a longitudinal study of the community-dwelling elderly in China. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:2009. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S138287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kobayashi K, et al. Measures and effects on prevention of fall: the role of a fall working group at a university hospital. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2017;79(4):497. doi: 10.18999/nagjms.79.4.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou H, et al. Risk factors for falls among older community dwellers in Shenzhen. China Inj Prev. 2019;25(1):31–35. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2017-042597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carty CP, et al. Reactive stepping behaviour in response to forward loss of balance predicts future falls in community-dwelling older adults. Age Ageing. 2014;44(1):109–115. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang VC, Do MT. Risk factors for falls among seniors: implications of gender. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;181(7):521–531. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Florence CS, et al. Medical costs of fatal and nonfatal falls in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(4):693–698. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.James MK, et al. Characterization of fall patients: does age matter? J Saf Res. 2018;64:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2017.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nevitt MC, et al. Risk factors for recurrent nonsyncopal falls: a prospective study. Jama. 1989;261(18):2663–2668. doi: 10.1001/jama.1989.03420180087036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tinetti ME, Speechley M, Ginter SF. Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(26):1701–1707. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198812293192604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burton E, et al. Falls prevention in community care: 10 years on. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:261. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S153687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Close J, et al. Prevention of falls in the elderly trial (PROFET): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1999;353(9147):93–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tinetti ME, et al. A multifactorial intervention to reduce the risk of falling among elderly people living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(13):821–827. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409293311301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mills KM, et al. An economic evaluation of preventing falls using a new exercise program in institutionalized elderly. J Phys Act Health. 2018;15(6):397–402. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2017-0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schott N, Tietjens M. Exploring the mediating role of social support and fall efficacy on the association of falls on physical activity: a cross-sectional study in an assisted-living population. J Aging Phys Act. 2018:1–27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Han BH, Ferris R, Blaum C. Exploring ethnic and racial differences in falls among older adults. J Community Health. 2014;39(6):1241–1247. doi: 10.1007/s10900-014-9852-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pluijm SM, et al. A risk profile for identifying community-dwelling elderly with a high risk of recurrent falling: results of a 3-year prospective study. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(3):417–425. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-0002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu C-Y, et al. Incorporating development stratification of Taiwan townships into sampling design of large scale health interview survey. J Health Manag. 2006;4(1):1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stevens JA, Sogolow ED. Gender differences for non-fatal unintentional fall related injuries among older adults. Injury Prevention. 2005;11(2):115–119. doi: 10.1136/ip.2004.005835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fallon LF, Jr, Awosika-Olumo A, Fulks JS. Factors related to accidents and falls among older individuals. Traumatology. 2002;8(4):205–210. doi: 10.1177/153476560200800403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kharicha K, et al. Health risk appraisal in older people 1: are older people living alone an ‘at-risk’group? Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(537):271–276. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schiller JS, Kramarow EA, Dey AN. Fall injury episodes among noninstitutionalized older adults: United States, 2001-2003. Adv Data. 2007;(392):1–16. [PubMed]

- 23.Foley AL, et al. Association between the geriatric giants of urinary incontinence and falls in older people using data from the Leicestershire MRC incontinence study. Age Ageing. 2011;41(1):35–40. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afr125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haylen BT, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. J Assoc Chartered Physiother Womens Health. 2012;110:33. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abdulla A, et al. Guidance on the management of pain in older people. Age Ageing. 2013;42:i1–57. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stubbs Brendon, Binnekade Tarik, Eggermont Laura, Sepehry Amir A., Patchay Sandhi, Schofield Pat. Pain and the Risk for Falls in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2014;95(1):175-187.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.08.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stubbs B, et al. Pain is associated with recurrent falls in community-dwelling older adults: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Med. 2014;15(7):1115–1128. doi: 10.1111/pme.12462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.GholamHosseini H, et al. A multifactorial falls risk prediction model for hospitalized older adults. In Engineering in medicine and biology society (EMBC), 2014 36th Annual International Conference of the IEEE. IEEE. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Valderrama-Hinds LM, et al. Falls in Mexican older adults aged 60 years and older. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2018:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Lafargue G, Noël M, Luyat M. In the elderly, failure to update internal models leads to over-optimistic predictions about upcoming actions. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e51218. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clemson L, et al. The effectiveness of a community-based program for reducing the incidence of falls in the elderly: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(9):1487–1494. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerson LW, Camargo CA, Jr, Wilber ST. Home modification to prevent falls by older ED patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23(3):295–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2005.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cox J, et al. Factors associated with falls in hospitalized adult patients. Appl Nurs Res. 2015;28(2):78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hitcho EB, et al. Characteristics and circumstances of falls in a hospital setting: a prospective analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(7):732–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30387.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naseri C, et al. Reducing falls in older adults recently discharged from hospital: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2018;47(4):512–519. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afy043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Health Promotion Administration, National Health Research Institutes, Food and Drug Administration, and Ministry of Health and Welfare of Taiwan but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available with permission of Health Promotion Administration, National Health Research Institutes, Food and Drug Administration, and Ministry of Health and Welfare of Taiwan.