Abstract

Background & aims

Gaucher disease (GD) is a multisystemic disease. Liver involvement in GD is not well characterised and ranges from hepatomegaly to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. We aim to describe, and assess the effect of treatment, on the hepatic phenotype of a cohort of patients with GD types I and II.

Methods

Retrospective study based on the review of the medical files of the Gaucher Reference Centre of the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, Brazil. Data from all GD types I and III patients seen at the centre since 2003 were analysed. Variables were compared as pre- (“baseline”) and post-treatment (“follow-up”).

Results

Forty-two patients (types I: 39, III: 3; female: 22; median age: 35 y; enzyme replacement therapy: 37; substrate reduction therapy: 2; non-treated: 3; median time on treatment-MTT: 124 months) were included. Liver enzyme abnormalities, hepatomegaly, and steatosis at baseline were seen in 19/28 (68%), 28/42 (67%), and 3/38 patients (8%), respectively; at follow-up, 21/38 (55%), 15/38 (39%) and 15/38 (39%). MRI iron quantification showed overload in 7/8 patients (treated: 7; MTT: 55 months), being severe in 2/7 (treated: 2/2; MTT: 44.5 months). Eight patients had liver biopsy (treated: 6; MTT: 58 months), with fibrosis in 3 (treated: 1; time on treatment: 108 months) and steatohepatitis in 2 (treated: 2; time on treatment: 69 and 185 months). One patient developed hepatocellular carcinoma.

Conclusions

GD is a heterogeneous disease that causes different patterns of liver damage even during treatment. Although treatment improves the hepatocellular damage, it is associated with an increased rate of steatosis. This study highlights the importance of a follow-up of liver integrity in these patients.

Keywords: Gaucher disease; Enzyme replacement therapy; Liver steatosis; Hemosiderosis; Biopsy, large-core needle; Cholelithiasis

1. Introduction

Gaucher disease (GD) (OMIM #230800, #230900 and #231000) is an autosomal recessive disorder most frequently caused by biallelic pathogenic variants in the GBA1 gene that codes for glucocerebrosidase (GCase). The impaired activity of GCase causes glucosylceramide (GlcCer) to build up into the lysosomes of the reticuloendothelial system cells, mainly macrophages that become engorged and dysfunctional being thus called “Gaucher cells” [1]. The incidence of GD ranges between 1:50,000 and 1:100,000 in the general population, and is about 1:855 in the Ashkenazi Jewish population [2]. GD is broadly categorised in three types, according to neurological manifestations: type I, or “non-neuronopathic”; type II, or “acute neuronopathic”; and type III, or “chronic neuronopathic”.

The manifestations of GD are multisystemic with a complex pathophysiologic process that arises from the infiltration of organs by Gaucher cells, the low-grade inflammation promoted by cells whose intracellular signalling is disrupted by the accumulation of GlcCer [3,4], and other factors such as aberrant complement activity [5,6] and dysfunctional autophagy [7,8]. The main signs and symptoms of GD include hepatosplenomegaly, anaemia, thrombocytopenia, bone deformities and pain, osteonecrosis, restrictive pulmonary disease, and neurological compromise in patients with GD type II and III [1,2] which cause significant impairment in life quality and reduction of life expectancy [9,10]. Treatment of GD is currently available in two modalities: enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) and substrate reduction therapy (SRT). The former is the most established treatment, consisting in the fortnightly infusion of recombinant GCase which is uptaken by the macrophages' lysosomes, decreasing the GlcCer build-up [1,2,11]. Imiglucerase (Sanofi Genzyme Corporation, Cambridge, MA, USA), taliglucerase alfa (Protalix Biotherapeutics, Carmiel, Israel), and velaglucerase alfa (Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Tokyo, Japan) are the currently available enzymes with no detectable difference in efficacy or safety profile known between them [1,12, [13], [14], [15], [16]]. SRT is administered orally once or twice daily and works decreasing the production of GlcCer which consequently decreases its storage [17]. The currently SRT FDA-approved compounds are miglustat and eliglustat. ERT and/or SRT are not indicated for GD type II patients.

The extent of liver damage in GD is still subject of debate – first reports were limited to hepatomegaly, however it is currently known that patients are at increased risk for focal fibrosis, cholelithiasis, steatosis, haemosiderosis, overt cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [18,19]. Recent studies [20,21] have shown that liver stiffness is increased in a large proportion of patients with GD, suggesting that fibrosis may be a pervasive process even in patients with apparent controlled disease, and also that it is correlated to disease severity, making it an important cause of morbidity to be addressed in this population.

In this study, we aimed at characterising the liver involvement in a cohort of patients with GD type I and III, and the effect of ERT/SRT on those variables.

2. Methods

This is a retrospective study, based on the review of the medical records of the GD types I and III patients followed at the Gaucher Reference Centre of the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, Brazil (GRC-HCPA) from 2003 to 2018. HCPA is a public, university hospital located in Southern Brazil. Inclusion criteria were: a) having biochemical or genetic diagnosis of GD; b) not having any other primary liver disease, as determined by clinical and laboratory features and serological screening for hepatitis B and C.

At the GRC-HCPA, patients have regular appointments every 3–4 months and most exams are made in an annual basis unless an acute event prompts a more frequent evaluation. The following exams were performed at baseline for most patients: complete blood count, chitotriosidase activity, aspartate-transaminase (AST), alanine-transaminase (ALT), and abdominal ultrasonography (US). The following exams are performed yearly: AST, ALT, γ-glutamyltransferase (γGT), direct bilirubin (DB), indirect bilirubin (IB), prothrombin time, alkaline phosphatase, total and fractional cholesterol, triglycerides, serum creatinine, blood urea, calcium, phosphorus, US, serum protein electrophoresis, serum immunoglobulins, transferrin saturation/iron-binding capacity, and serum iron. The following exams are performed every three months: complete blood count, serum ferritin, and chitotriosidase activity. All patients are tested for serological markers of viral hepatitis at initiation of treatment and again according to clinical indication. Alpha-foetoprotein (AFP) is not ordered for patients without cirrhosis due to its dubious efficacy as a screening test for hepatocellular carcinoma [22]. The presence of hepatomegaly was ascertained by US or by physical exam (when US was not available). The presence of steatosis was assessed by US. Elastography for fibrosis assessment is not routinely performed. Other exams are performed according to clinical indication [23]. All patients had genotyping of GBA and HFE by next-generation sequencing.

Immunological and iron metabolism findings of our cohort have already been described by Vairo et al. [24] and Koppe et al. [25], respectively.

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software (IBM Inc., v.18); for comparison of frequencies of categorical variables, the χ2 test was used. Patients were compared regarding the findings before the onset of treatment (“baseline” data points) and during treatment until last follow-up (“follow-up” data points). Findings were considered abnormal at baseline or at follow up if altered in at least two measurements for each datapoint, or one measurement when it was the only one available.

3. Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of HCPA (CEP/HCPA), Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil (projects #13–0537 and #15–0083). All studies were conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects or, when <18 years-old, from their parents.

4. Results

4.1. Subjects

Forty-two patients were included (n = 39, type I; n = 3, type III; female = 22; median time on treatment: 124 months). One patient with GD type I (pt 26D) was excluded from the follow-up data analysis due to diagnosis of active chronic hepatitis B. One patient with GD type I (pt 26A) had serological evidence of spontaneously cured hepatitis B. No other patients had signs of other liver diseases, such as drug-related liver injury, autoimmune hepatitis, or viral hepatitis.

No patient had a history of blood transfusions in the past. A total of 36 patients had measurements of serum transferrin saturation after treatment; of these, 6 had decreased values and 5 had increased values (Supplementary Table 1). Four patients had used ferrous sulphate supplements in the past, one of them only during pregnancy (Supplementary Table). No patient was homozygous or compound heterozygous for pathogenic variants in the HFE gene, ruling out the concomitant diagnosis of HFE-associated haemochromatosis (MIM: #235200).

4.2. Laboratory findings

Laboratory findings of all patients are shown in Table 1

Table 1.

Liver enzymes in patients with Gaucher disease.

| Patient | Age | Gender | GBA Genotype | Sx | Baseline |

Time on treatment | Follow-up |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (y) | AST | ALT | GGT | DB | IB | (months) | AST | ALT | GGT | DB | IB | ||||

| 1A | 7 | F | N370S/G202R | No | - | - | - | - | - | None | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1B | 22 | M | N370S/G202R | No | - | - | - | - | - | I(168) | N | N | N | ↑ | N |

| 2 | 20 | M | L444P/L444P | No | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | N | N | I(110) T(1) V(81) | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | N | N |

| 3 | 20 | F | N370S/L444P | No | - | - | - | - | - | None | - | - | - | - | - |

| 4A | 22 | F | N370S/L444P | No | N | N | N | N | N | I(68) | N | N | N | N | N |

| 4B | 36 | F | N370S/L444P | No | N | ↑ | N | N | N | I(19) T(1) I(90) | N | N | N | N | N |

| 5 | 23 | F | N370S/RecNciI | No | ↑ | ↑ | - | - | - | I(184) | N | N | ↑ | N | N |

| 6 | 23 | F | N370S/L444P | No | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | N | N | T(34) | ↑ | N | N | N | N |

| 7 | 24 | M | N370S/N370S | No | - | - | - | - | - | I(131) | N | N | N | ↑ | N |

| 8 | 24 | F | N370S/N370S | No | N | ↑ | N | - | - | I(156) | N | N | N | ↑ | ↑ |

| 9 | 25 | F | N370S/L444P | No | N | N | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | I(113) | N | N | N | ↑ | ↑ |

| 10 | 26 | M | N370S/R120W | No | N | N | N | N | ↑ | I(202) | N | N | N | ↑ | ↑ |

| 11A | 26 | M | L444P/L444P | Yes | - | - | - | - | - | I(176) | N | ↑ | N | ↑ | N |

| 11B | 29 | F | L444P/L444P | Yes | - | - | - | - | - | I(175) | N | ↑ | N | N | N |

| 12 | 27 | M | N370S/c.1328+1G>A | No | N | N | N | ↑ | N | I(159) | N | N | N | ↑ | N |

| 13 | 27 | F | N370S/RecNciI | No | - | - | - | - | - | I(120) T(1) I(6) E(41) I(8) E(16) | N | N | N | N | N |

| 14 | 27 | M | N370S/L444P; c1483G>C | No | ↑ | ↑ | N | - | - | I(237) T(13) | ↑ | ↑ | N | ↑ | ↑ |

| 15 | 28 | F | N370S/L461P; c.1515+1G>T | No | - | - | - | - | - | I(211) | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | N | N |

| 16 | 28 | M | N370S/L444R | No | - | - | - | - | - | A(31) I(227) | N | ↑ | N | N | N |

| 17 | 31 | M | N370S/RecNciI | No | - | - | - | - | - | I(109) T(2) I(9) T(80) | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | N | N |

| 18 | 33 | F | N370S/L444P | No | N | N | - | - | - | M(7) I(115) | N | N | N | N | N |

| 19A | 35 | M | N370S/L444P | No | ↑ | N | ↑ | N | N | I(75) | N | N | N | ↑ | N |

| 19B | 41 | M | N370S/L444P | Yes | N | ↑ | - | ↑ | ↑ | I(74) T(3) I(88) | N | N | N | N | ↑ |

| 19C | 52 | M | N370S/L444P | No | N | ↑ | ↑ | - | - | I(6) T(1) I(81) | N | N | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| 20 | 36 | F | N370S/R163* | No | - | - | - | - | - | I(210) | ↑ | N | ↑ | N | N |

| 21 | 36 | F | N370S/RecNciI | Yes | - | - | - | - | - | A(25) I(28) T(3) I(53) | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | N | N |

| 22A | 37 | M | N370S/L444P | No | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | N | N | I(5) T(81) | ↑ | N | ↑ | N | N |

| 22B | 39 | F | N370S/L444P | No | N | N | N | N | N | I(22) T(2) I(14) E(77) | ↑ | N | N | N | N |

| 23 | 38 | F | N370S/RecNciI | No | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | I(38) | ↑ | N | ↑ | N | N |

| 24 | 45 | M | N370S/RecNciI | No | N | N | - | N | N | I(102) T(3) I(29) T(50) | N | N | N | ↑ | N |

| 25A | 48 | F | E349K/S366N | No | N | N | ↑ | N | N | M(11) T(1) I(62) | N | N | N | N | N |

| 25B | 52 | F | E349K/S366N | No | N | N | N | N | N | M(30) T(14) | N | N | N | N | N |

| 26A | 53 | M | N370S/RecNciI | No | N | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | N | I(89) | N | N | N | ↑ | N |

| 26B | 57 | M | N370S/RecNciI | No | ↑ | ↑ | N | N | N | I(79) | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| 26C | 63 | F | N370S/RecNciI | No | N | N | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | I(73) | N | N | N | ↑ | ↑ |

| 26D | 51 | F | N370S/RecNciI | Yes | - | - | - | N | N | I(96) T(5) I(13) T(79) | - | - | - | - | - |

| 27 | 62 | F | N370S/RecNciI | No | N | N | - | - | - | I(124) T(2) I(8) T(81) | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | N | N |

| 28 | 62 | M | N370S/RecNciI | Yes | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | N | I(34) T(2) I(90) | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| 29A | 64 | M | N370S/N370S | No | N | N | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | I(10) T(2) I(9) T(81) | N | N | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| 29B | 65† | M | N370S/N370S | No | N | N | ↑ | N | N | I(19) T(2) I(8) T(14) | N | N | ↑ | N | ↑ |

| 30 | 67 | F | N370S/L444R | Yes | N | N | N | N | N | I(12) M(25) I(49) | N | N | N | N | N |

| 31 | 62† | M | N370S/RecNciI | No | - | - | - | - | - | None | - | - | - | - | - |

Values considered to be elevated were so in at least two measurements while on treatment. Patients sharing the same number are siblings, except for patient 26D who is a cousin of patients 26A, 26B, and 26C. Patients 5, 7, 8 , 14, 19A, 19B, 19C, 21, 22A, and 24 have a low adherence to treatment (less than 75% of programmed yearly infusions performed). Sx = splenectomy; M = male; F = female; N = normal; A = alglucerase; I = imiglucerase; T = taliglucerase alfa; V = velaglucerase alfa; E = eliglustat; - = no value available. †age of death. Reference values: ALT < 34 U/L; AST < 33 U/L; GGT < 40 U/L; DB < 0.4 mg/dL; IB < 0.9 mg/dL.

Out of the 28 patients with liver enzymes (AST, ALT, or γGT) data at baseline, 19/28 (68%) had abnormal liver enzymes in at least two measurements. At follow-up, 21/38 (68%) had abnormalities in at least one liver enzyme in at least two measurements. History was positive for excessive alcohol intake in two patients (19B and 26B).

Serum transferrin saturation, immunoglobulins, and serum protein electrophoresis results during treatment can be found in the supplementary table. Immunoglobulin measurements and serum protein electrophoresis results were available for 36 patients during treatment; of these, 26 had an abnormal serum immunoglobulin measurement at least twice and 20 had increased γ-globulins in serum electrophoresis at least twice.

4.3. Liver ultrasound findings

Liver US reports were available from 39 patients (baseline = 39; follow-up = 38) (Table 2, Table 3). Hepatomegaly was present in 28/42 (67%) of patients at baseline and in 15/38 (39%) of patients at follow-up.

Table 2.

US findings from GD patients at baseline.

| Patient | Age (y) |

BMI | Steatosis | Hepatomegaly | Cholelithiasis | Ferritin (ng/dL) |

MetSa | Liver biopsy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1A | 7 | 15.9 | No | No | No | 378 | No | No |

| 1B | 8 | 16.1 | No | Yes | No | – | No | No |

| 2 | 1 | 16.9 | No | Yes | No | – | No | No |

| 3 | 15 | 17.3 | Yes | No | No | 174.6 | No | No |

| 4A | 16 | 21.8 | No | No | No | 284.8 | No | No |

| 4B | 26 | 22.7 | Yes | Yes | Yes | 328.5 | No | No |

| 5 | 8 | 15.1 | No | Yes | No | – | No | No |

| 6 | 20 | 22.6 | No | Yes | No | 219.3 | No | Yes |

| 7 | 6 | 14.6 | No | Yes | No | – | No | No |

| 8 | 7 | 12 | No | Yes | No | 97.3 | No | No |

| 9 | 17 | 18.3 | No | Yes | No | 166 | No | No |

| 10 | 9 | 14.5 | No | Yes | No | – | No | No |

| 11A | – | 14.1 | – | Yes | No | – | No | No |

| 11B | – | – | – | Yes | No | – | No | No |

| 12 | 12 | 17.3 | No | No | No | – | No | No |

| 13 | 14 | 23 | No | No | No | – | No | No |

| 14 | 6 | 16.2 | No | Yes | No | – | No | No |

| 15 | 11 | 12.5 | No | Yes | No | – | No | No |

| 16 | – | 15.2 | – | Yes | No | – | No | No |

| 17 | 24 | 16.8 | No | Yes | No | – | No | No |

| 18 | 17 | 21.6 | No | Yes | No | – | No | No |

| 19A | 39 | 30.2 | No | Yes | Yes | 758.3 | No | No |

| 19B | 28 | 22.2 | No | Yes | No | – | No | No |

| 19C | 43 | 26.5 | No | No | No | 951.8 | No | No |

| 20 | 18 | 21.9 | No | Yes | No | – | No | No |

| 21 | 13 | 16.6- | No | Yes | No | – | No | No |

| 22A | 30 | 24 | No | Yes | No | 469.6 | No | No |

| 22B | 29 | 23.2 | No | Yes | No | 213.3 | No | No |

| 23 | 34 | 25.3 | No | No | No | 835 | Yes | Yes |

| 24 | 22 | 24.3- | No | No | No | – | No | No |

| 25A | 42 | 23.4 | No | Yes | Yes | 754.2 | No | No |

| 25B | 43 | 30.2 | Yes | Yes | Yes | 860.7 | No | No |

| 26A | 44 | 25 | No | No | No | 811 | No | No |

| 26B | 50 | 31.4 | No | No | No | 1409 | Yes | No |

| 26C | 57 | 23.5 | No | No | No | 1593 | No | No |

| 26D | 34 | 19.3 | No | Yes | No | – | No | No |

| 27 | 44 | – | No | Yes | No | – | No | No |

| 28 | 52 | 24 | No | Yes | No | 3392 | Yes | Yes |

| 29A | 55 | 28.5 | No | No | Yes | 1698 | Yes | No |

| 29B | 61 | 27.2 | No | No | Yes | 778.2 | No | No |

| 30 | 60 | 29.8 | No | Yes | No | 1972 | Yes | No |

| 31 | 62 | 17.7 | No | No | No | 1343 | No | No |

y = years-old; US = ultrasonography; BMI = body-mass index; MetS = metabolic syndrome. Ferritin RV <150 ng/dL for women, <300 ng/dL for men.

Metabolic syndrome is defined as the presence of at least three of the following: obesity, high triglycerides level, increased blood pressure, and elevated fasting blood glucose (reduced HDL level was not considered as a criterion because it is a feature of GD).

Table 3.

US from GD patients at follow-up.

| Patient | Age (y) |

Time on treatment (months) |

Steatosis | Hepatomegaly | Cholelithiasis | BMI | Ferritin (ng/dL) |

MetS during treatmenta | Liver biopsy during treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1A | – | T(7) | – | No | – | 17.4 | 308 | No | No |

| 1B | 20 | I(168) | No | No | No | 28.6 | 485 | No | No |

| 2 | 20 | I(110) T(1) V(81) | Yesb | Yes | Yes | 21.7 | 254 | No | No |

| 3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 4A | – | – | – | No | No | 24.4 | 312.2 | No | No |

| 4B | 36 | I(19) T(1) I(89) | No | Yes | Yes | 25.9 | 57.3 | No | No |

| 5 | 22 | I(177) | No | No | No | 22.7 | 84.7 | No | No |

| 6 | 23 | T(33) | No | No | No | 22.4 | 172.6 | No | No |

| 7 | 17 | I(68) | No | No | No | 19.2 | 885.3 | No | No |

| 8 | 25 | I(156) | Yesb | Yes | No | 20.5 | 508.3 | No | No |

| 9 | 26 | I(112) | No | No | No | 22.7 | 94.6 | No | No |

| 10 | 25 | I(200) | No | Yes | No | 24.7 | 547 | No | No |

| 11A | 26 | I(174) | Yes | Yes | Yes | 18.8 | 242.6 | No | No |

| 11B | 28 | I(146) | No | Yes | No | 27.8 | 285.9 | No | No |

| 12 | 25 | I(126) | No | Yes | No | 23.1 | 546.3 | No | No |

| 13 | 27 | I(120) T(1) I(6) E(41) I(8) E(9) | Noc | No | Yes | 28.8 | 611.6 | No | Yes |

| 14 | 23 | I(189) | No | Yes | No | 24.9 | 619.9 | No | No |

| 15 | 29 | I(216) | Yesb | Yes | No | 26.6 | 311.1 | No | No |

| 16 | 25 | A(31) I(222) | No | No | No | 20.6 | 569.8 | No | No |

| 17 | 29 | I(109) T(2) I(9) T(55) | No | No | No | 30.6 | 325.8 | No | No |

| 18 | 33 | M(7) I(111) | No | Yes | Yes | 25.3 | 278.8 | Yes | No |

| 19A | 45 | I(67) | Yesb | No | Yes | 32 | 66.5 | No | No |

| 19B | 34 | I(71) | No | No | No | 27.8 | 585.3 | No | No |

| 19C | 51 | I(6) T(1) I(80) | Yesb | Yes | No | 28.3 | 1084 | Yes | No |

| 20 | 36 | I(207) | No | No | Yes | 25.6 | 574.2 | No | No |

| 21 | 32 | A(25) I(28) T(3) I(4) | No | No | No | 22.7 | 415.7 | No | No |

| 22A | 36 | I(5) T(65) | No | Yes | No | 26.8 | 463.8 | No | No |

| 22B | 40 | I(22) T(2) I(14) E(70) | Yes | No | No | 30 | 32 | Yes | No |

| 23 | 38 | I(35) | Yesb | No | Yes | 30.7 | 427.2 | No | No |

| 24 | 44 | I(102) T(3) I(29) T(38) | No | Yes | No | 28.7 | 247.9 | No | No |

| 25A | 48 | M(11) T(1) I(55) | Yes | No | Yes | 25.8 | 611.9 | No | Yes |

| 25B | 51 | M(30) T(10) | Yes | No | Yes | 31.9 | 1053 | No | Yes |

| 26A | 52 | I(80) | No | No | No | 24.1 | 480.6 | No | No |

| 26B | 58 | I(76) | Yes | No | No | 32.2 | 1457 | Yes | Yes |

| 26C | 62 | I(66) | No | No | No | 21.6 | 624.8 | No | No |

| 27 | 61 | I(124) T(2) I(8) T(71) | Yes | No | No | 26.6 | 1052 | Yes | No |

| 28 | 62 | I(34) T(2) I(88) | No | No | No | 22.3 | 543.2 | No | Yes |

| 29A | 65 | I(10) T(2) I(9) T(81) | Yes | No | Yes | 34.5 | 670 | Yes | No |

| 29B | 65 | I(19) T(2) I(8) T(14) | Yes | Yes | Yes | 29.7 | 686 | Yes | No |

| 30 | 67 | I(12) M(25) I(47) | No | Yes | No | 30.5 | 1103 | Yes | Yes |

| 31 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

y = years-old; BMI = body mass index; I = imiglucerase; T = taliglucerase alfa; V= = velaglucerase alfa; E = eliglustat; A = alglucerase; M = miglustat.

Metabolic syndrome is defined as the presence of at least three of the following: obesity, high triglycerides level, increased blood pressure, and elevated fasting blood glucose (reduced HDL level was not considered as a criterium because it is a feature of GD).

Steatosis regressed within two years of US detection.

Steatosis at liver biopsy only.

Steatosis was present in 3/39 (8%) of patients at baseline and in 15/38 (39%) at follow-up. In 6 patients, there was regression of steatosis within 2 years of US detection. Of these, none had any significant change in body-mass index (BMI) but two had changes in the ERT regimen (for patient 15, there was an increase in the imiglucerase dosage from 45 IU/Kg to 60 IU/Kg; for patient 19C, there was a switch from taliglucerase alfa to imiglucerase). Twelve out of the 16 patients (75%) with steatosis were overweight or obese, with 4 patients (two whose steatosis regressed, one that maintains the finding, and one that denied treatment and further follow-up) having a normal BMI. A significant difference was found between the frequency of overweight/obesity in patients with and without persistent steatosis (77.8% vs 40%, p = .047, Pearson's χ2). Blood lipid levels were available for 7 of the 9 patients (78%) with non-regressing steatosis during treatment. All 7 patients had dyslipidaemia (four with high triglycerides, three with high total cholesterol and LDL, and five with low HDL). Levels were available for 31 patients without non-regressing steatosis – of these, 28 (90.3%) had dyslipidaemia (10 with high triglycerides, 5 with high total cholesterol and LDL, and 25 with low HDL). No significant difference was found between patients with and without non-regressing steatosis and the presence of dyslipidaemia (p = .814, Pearson's χ2).

Twelve patients in the cohort had cholelithiasis, and 7 of them underwent cholecystectomy (pts. 13, 18, 19A, 20, 23, 25A, and 25B). Patient 23 had cholecystectomy before initiation of treatment for GD. Eight out of the patients with cholelithiasis were overweight or obese, but no significant difference in the prevalence of overweight/obesity was found between the patients with and without cholelithiasis (66.7% vs 40.7%, p = .135, Pearson's χ2).

Other US findings observed in the cohort were: cysts, haemangioma, solid nodule compatible with an adenoma or a haemangioma, portal hypertension that resolved with initiation of ERT, and cirrhosis with HCC. The two cysts of unknown diagnosis were present in a pair of brothers with GD type I who also had steatosis (pts 29A and 29B). The older brother passed away at the age of 65 due to multiple myeloma. The cyst in the younger brother, now aged 65, is 5 mm in diameter and is stable since it was diagnosed 2 years ago. The patient with cirrhosis (pt 28) is a 62-year-old male splenectomised GD type I patient described elsewhere 26.

4.4. Magnetic resonance iron quantification

Liver iron quantification by magnetic resonance had been performed in 7 patients with GD type I on treatment with ERT (Table 4). Iron overload was observed in 6/7 (85%) patients, ranging from 50 to 280 μmol/g (reference value (RV): <36). All the patients with iron overload had high ferritin values, ranging from 244 to 3011 ng/mL. Two patients had a high level of iron overload (>79 μmol/g [27]) – one was a 55-year-old male patient whose MRI showed a concentration of 280 μmol/g of iron in the liver, with ferritin at 1813 ng/mL and transferrin saturation at 47.3% (RV 20–45%), steatosis, and a heterozygous c.845G>A, p.Cys282Tyr variant in HFE gene. The other patient with high iron levels (210 μmol/g) is a 64-year-old female who had ferritin at 3011 ng/dL and low transferrin saturation at 17.4%. There were no signs of steatosis and she doesn't harbour any pathogenic variant in HFE gene.

Table 4.

Patients screened for hepatic iron overload with magnetic resonance.

| Patient | Age (y) | Gender | HFE genotype | Ferritin (ng/dL) | Transferrin saturation | Treatment at exam | Time on treatment (months) | Iron concentration (μmol/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 26 | M | p.Cys282Tyr/wt | 525 | – | I | I(196) | 70 |

| 15 | 24 | F | wt/wt | 298.4 | 30.7% | I | I(160) | 50 |

| 23 | 34 | F | p.His63Asp/wt | 835 | 25% | None | – | 5 |

| 25A | 44 | F | p.His63Asp/wt | 937.1 | 50.8% | I | M(11) T(1) I(8) | 55 |

| 26B | 55 | M | p.Cys282Tyr/wt | 1813 | 47.2% | I | I(55) | 280 |

| 27 | 59 | F | wt/wt | 347 | 44% | T | I(124) T(2) I(8) T(41) | 65 |

| 30 | 63 | F | wt/wt | 3011 | 17.4% | M | I(12) M(22) | 210 |

All patients are type I. Ferritin and transferrin saturation values given are approximately from the time of the MR iron quantification. Reference values: ferritin (males) <300 ng/mL; ferritin (females) < 150 ng/mL; transferrin saturation 25–45%; iron concentration < 6 μmol/g. y = years-old; HFE = homeostatic iron regulator gene; F = female; M = male; wt = wild-type; I = imiglucerase; T = taliglucerase; M = miglustat.

4.5. Liver biopsy

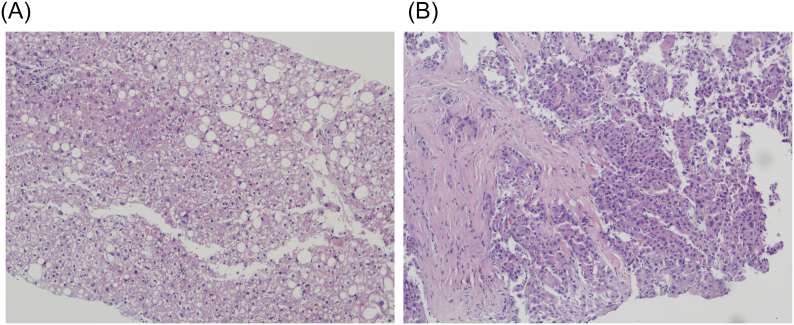

Six patients with GD type I had a liver biopsy done (Fig. 1; Table 5) when on-treatment. One patient was found to have Gaucher cells in the liver parenchyma; One patient had atypical Gaucher cells in a cirrhotic parenchyma with severe iron overload in hepatocytes and Kupffer cells, and, in a subsequent biopsy, a moderately differentiated HCC [26]. Two patients who have had mild to moderate steatosis on ultrasound had a biopsy confirming macrovesicular steatosis – one also with evidence of cholestasis and a few foci of inflammation, and the other with mild haemosiderosis. Two patients had steatohepatitis with mild activity: a 27-year-old female with a BMI of 28.8 Kg/m2 who did not show any sign of steatosis in the ultrasound, had normal serum blood glucose and lipid profile except for a low HDL (which is expected in GD) and that was on SRT with eliglustat at the time of the biopsy; and a 58 year-old man had moderate-to-severe haemosiderosis of hepatocytes and Kupffer cells, elevated triglycerides and total and LDL cholesterol, and low HDL, albeit a normal blood glucose, and signs of steatosis in the liver ultrasound, and that was on ERT at the time of biopsy.

Fig. 1.

A: Haematoxylin and eosin, 200× magnification. Liver biopsy of patient 26B showing macrovesicular steatosis in approximately 5% of hepatocytes, as well as a small focus of mixed inflammation (upper left corner). Fig. 1B: Haematoxylin and eosin, 400× magnification. Liver biopsy of patient 28 showing thick bridging fibrosis characteristic of cirrhosis, as well as substitution of the local hepatic parenchyma by moderately differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma cells.

Table 5.

Findings in the liver biopsy.

| Patient | Age (y) at biopsy | Treatment at biopsy (IU/Kg) |

Time on treatment (months) |

Inflammation | Steatosis | Siderosis | Gaucher cells | Fibrosis | Other findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 20 | None | – | No | No | No | Yes | Perisinusoidal | No |

| 13* | 27 | E | I(120) T(1) I(6) E(41) I(8) E(9) | Steatohepatitis | No | No | No | No | |

| 23* | 34 | None | – | No | No | No | Yes | Bridging | No |

| 25A* | 44 | I [30] | M(1) T(1) I(14) | Mild | Mild | Mild | Yes | No | Cholestasis |

| 25B* | 49 | M | M(11) | No | Mild | Mild | No | No | No |

| 26B | 56 | I [30] | I(69) | Steatohepatitis | Severe | No | No | No | |

| 28 | 60 | I [15] | I(34) T(2) I(72) | No | No | Severe | Yes | Cirrhosis | HCC |

| 30* | 63 | M | I(12) M(22) | Mild | No | Moderate | Yes | No | Nuclear glycogenosis |

y = years-old; Sx = splenectomy; E = eliglustat; I = imiglucerase; M = miglustat; HCC = hepatocellular carcinoma. In patient 28, HCC was noted only in a second biopsy, performed 9 months after the first one. *patients with normal liver enzymes; see Table 1.

Two patients with GD type I underwent liver biopsy before treatment initiation. A 34-year-old female's biopsy showed bridging (stage 3) fibrosis and scattered Gaucher cells; in the other, a 20-year-old woman, peri-sinusoidal fibrosis was noted together with high serum AST, ALT, and γGT, and a normal liver ultrasound.

5. Discussion

For the past few decades, the liver involvement in GD has become subject of great importance in the patients' management. It is now recognised that hepatomegaly is only one of the manifestations of hepatic compromise in GD, and more attention is needed to all the possible comorbidities that may arise from it. In our cohort, we observed that a significant number of patients have mildly increased markers of hepatic and biliary damage before the treatment initiation and throughout the clinical follow-up, indicating that a low-grade process of liver damage is not fully corrected by the treatment. This finding resembles the study by James et al. from when effective treatment for GD was not available [28], in which most patients with GD had mild-to-moderate transaminase elevations. In more recent cohorts, these alterations have also been found in a lesser proportion of patients [20,21]. However, the impact of these alterations is still unclear. Nascimbeni et al. have shown that levels of liver enzymes are not correlated with liver fibrosis [20]. The contribution of chronic liver damage to the development of other complications such as iron deposition, since chronic hepatitis and liver disease are strongly associated with hemosiderosis [29], has not been fully explored to date. The high frequency of patients with elevations in γGT may also be related to the known biliary alterations caused by GD [30] such as changes in bile composition, increased incidence of cholelithiasis, or with the chronic inflammatory process that happens in the disease [3,4,24] causing biliary damage.

A significant proportion of patients had bilirubin elevations, both before and during treatment. Most elevated bilirubin values corresponded to direct bilirubin, which points toward a biliary cause rather than overproduction (e.g., haemolysis). It is difficult to establish a clinical significance of this finding, It is known that GlcCer and glucosylsphingosine (GlcSph) [31,32] interact with a series of transporters of the ABC (ATP-binding cassette) family, including ABCB1 [33]; It is also known that the bile of patients with GD is different than in the general population, being composed of lower total lipid concentration and, in some patients, high relative concentration of sphingolipids [30]; and finally, that ABC transporters such as ABCB1 are capable of transporting GlcCer and GlcSph [34] across cell membranes, and are modulated by these complex lipids [33]. ABCB1 is localized at the canalicular membrane contributing to the bile formation and xenobiotic excretion [35] – it is possible that, due to ABC-mediated efflux, the higher levels of GlcCer present in bile [36] lead to canalicular disturbances that may cause an impaired flow of bilirubin, leading to the slightly high levels of DB observed.

Iron homeostasis is being increasingly recognised as a key factor of GD's pathogenesis [25]. In a recent article by Lefèbvre et al. [37], it was reported that a local overstimulation of hepcidin related to the lower enzymatic activity of GCase causes iron to be sequestered within macrophages and other cell types, leading to a lower level of free iron, transferrin-bound iron and a higher production of ferritin by the liver. In our study, we observed that several patients with GD have high hepatic iron levels as measured by magnetic resonance, two of the tested patients with levels consistent with severe iron overload – whilst in one patient it may be caused by other risk factors such as alcoholism, steatohepatitis, and a pathogenic HFE variant, in the other patient the only obvious risk factor is obesity, and the low transferrin value with exceedingly high ferritin confirm the predictions by Lefèbvre et al. Other studies have observed increase liver iron concentration in GD patients [38], with a positive correlation with serum ferritin concentration. On liver biopsy, positive iron staining has been described extensively [28,39] both in Kupffer cells and in hepatocytes, similar to what was observed in our cohort. Data on pre- (median = 19%, n = 8 patients) and post-treatment (median = 28%, n = 13 patients) values for serum transferrin saturation in this cohort have been described by Koppe et al [25], with no significant difference (p = .138).

The main ultrasound finding in our cohort was steatosis, with predominance in overweight/obese patients. Our findings differ from the Israeli cohort, which has a much lower prevalence of fatty liver and a higher prevalence of focal lesions [40]. In the Israeli study, 500 patients were evaluated by US, of which 39 had ultrasonographic evidence of hepatic disease – of these, two-thirds were on ERT and one-fourth was splenectomised. ERT is a potent inducer of weight gain due to slowing the increased basal metabolic rate of patients before treatment [19,41]; thus, it may be difficult to establish whether the high prevalence of steatosis is a manifestation of GD itself, a complication of its treatment, or a comorbidity. A significant proportion of our patients had dyslipidaemia, which indicates that metabolic syndrome may play a role as a confounder in the development of steatosis in these patients [42]. Remarkably, a young patient being treated with eliglustat that had a hepatic biopsy done during cholecystectomy was diagnosed with steatohepatitis, regardless of having no signs of steatosis. This case raises two questions: whether ultrasound can be relied upon as a mean of screening for liver disease in GD patients; and whether steatohepatitis may be a manifestation of GD, since the only known risk factor that the patient had for steatohepatitis (a BMI of 28.8 Kg/m2) is hardly considered enough for a sole causal factor; and, as the blood glucose and lipid levels of this patient were normal except for a low HDL, which is a marker of GD, dyslipidaemia and metabolic syndrome are not strongly suspected. Another possible cause for the steatohepatitis in this patient could be what is becoming known as “lean fatty liver disease” – that is, non-alcoholic steatosis (NAFLD) or steatohepatitis (NASH) in patients with few or no risk factors for such [43]. Although in the classical definition of “lean NASH” the patient's BMI is normally <25 Kg/m2 [43], despite some authors advocating for the use of a BMI of <30 Kg/m2 in Western populations [44], it is expected that patients with “non-lean NASH” are male, of older age, and have hypertension, insulin resistance, or hypercholesterolaemia - none of which is present in this patient [43]. It is speculated that lean NASH arises from “metabolic obesity” in non-obese people, which is reflected by the higher distribution of fat to the visceral intraabdominal organs [44,45], along with classical risk factors such as insulin resistance and hypercholesterolaemia [44] – none of which were present in this patient – and genetic predisposition due to polymorphisms in genes associated with lipid metabolism [44,46].

Liver fibrosis is shown to be increased in a significant proportion of patients [20], especially in those who were splenectomised [38], and it is a major risk factor for HCC [39]. Liver fibrosis is correlated with increased severity of GD [20], although its correlation with biomarkers of disease activity is still controversial [20,38]. In the pre-ERT era, when no specific treatment for GD was available, liver fibrosis was a common finding [28], and often culminated in a massive central area of hypocellular fibrotic tissue [47,48] that led to portal hypertension and other clinical manifestations of cirrhosis [28].

Cholelithiasis is a frequent comorbid process of GD with about 30–45% [49,50] lifetime incidence in these patients. Although the causes for this increased incidence are not completely elucidated, some authors speculate that the excretion of GlcCer in the bile may increase its lithogenicity, predisposing to the formation of gallstones [30,36,49]. In our cohort, we have observed a similarly increased prevalence of cholelithiasis in GD patients compared to the general population, with 12 patients affected in a total of 41.

6. Conclusion

In this study, we presented a comprehensive summary of the hepatic manifestations in a well-characterised cohort of patients with GD, showing that several patients have lingering alterations that may indicate a smouldering process of liver damage which is not completely avoided by standard therapy. It is also noticeable that many patients have liver steatosis or steatohepatitis, with a noticeable increase in prevalence during treatment with ERT, but it is still unclear whether it reflects a consequence from the treatment, a feature of the disease, or a coincidental finding.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank our undergraduate students Luciana Rizzon, Vitória Schütt Zizemer, and Ana Paula Becker, who helped with keeping the Reference Centre database updated. We are also grateful to the staff of the Medical Genetics Service - Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, Brazil for the support.

Financial support

This study was financed by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brazil (CAPES) and by the Fundo de Apoio a Pesquisa e Eventos (FIPE) of the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre.

All authors disclose no potential personal or financial conflicts of interest regarding this publication

RTS and IVDS designed the study, reviewed the literature, collected and analysed the data, and wrote the manuscript. IVDS supervised the study and obtained funding. FPV, ADD and MRAS helped analysing the data and reviewed the manuscript. SPB and MS performed the molecular analyses and reviewed the manuscript. MLAP reviewed the manuscript. CTSC helped collecting and analysing the histological data and reviewed the manuscript.

Author statement

All authors (Rodrigo Tzovenos Starosta, Filippo Pinto e Vairo, Alícia Dorneles Dornelles, Suélen Porto Basgalupp, Marina Siebert, Maria Lúcia Alves Pedroso, Carlos Thadeu Schmidt Cerski, Mário Reis Álvares-da-Silva, Ida Vanessa Doederlein Schwartz) disclose no potential personal or financial conflicts of interest regarding this publication.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymgmr.2019.100564.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Stirnemann J., Belmatoug N., Camou F. A review of Gaucher Disease pathophysiology, clinical presentation and treatments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18(2) doi: 10.3390/ijms18020441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GM P., Gaucher Disease D.A.H. 2000. Seattle, WA: GeneReviews. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aflaki E., Moaven N., Borger D.K. Lysosomal storage and impaired autophagy lead to inflammasome activation in Gaucher macrophages. Aging Cell. 2016;15(1):77–88. doi: 10.1111/acel.12409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mucci J.M., Cuello M.F., Kisinovsky I., Larroude M., Delpino M.V., Rozenfeld P.A. Proinflammatory and proosteoclastogenic potential of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from Gaucher patients: implication for bone pathology. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2015;55(2):134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pandey M.K., Burrow T.A., Rani R. Complement drives glucosylceramide accumulation and tissue inflammation in Gaucher disease. Nature. 2017;543(7643):108–112. doi: 10.1038/nature21368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pandey M.K., Grabowski G.A., Kohl J. An unexpected player in Gaucher disease: the multiple roles of complement in disease development. Semin. Immunol. 2018;37:30–42. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2018.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kinghorn K.J., Asghari A.M., Castillo-Quan J.I. The emerging role of autophagic-lysosomal dysfunction in Gaucher disease and Parkinson’s disease. Neural Regen. Res. 2017;12(3):380–384. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.202934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu E.A., Lieberman A.P. The intersection of lysosomal and endoplasmic reticulum calcium with autophagy defects in lysosomal diseases. Neurosci. Lett. 2018;697:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2018.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oliveira F.L., Alegra T., Dornelles A. Quality of life of brazilian patients with Gaucher disease and fabry disease. JIMD Rep. 2013;7:31–37. doi: 10.1007/8904_2012_136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cerón-Rodríguez M., Barajas-Colón E., Ramírez-Devars L., Gutiérrez-Camacho C., Salgado-Loza J.L. Improvement of life quality measured by Lansky Score after enzymatic replacement therapy in children with Gaucher disease type 1. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2018;6(1):27–34. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennett L.L., Mohan D. Gaucher disease and its treatment options. Ann. Pharmacother. 2013;47(9):1182–1193. doi: 10.1177/1060028013500469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Rossum A., Holsopple M. Enzyme replacement or substrate reduction? A review of Gaucher Disease treatment options. Hosp. Pharm. 2016;51(7):553–563. doi: 10.1310/hpj5107-553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ben Turkia H., Gonzalez D.E., Barton N.W. Velaglucerase alfa enzyme replacement therapy compared with imiglucerase in patients with Gaucher disease. Am. J. Hematol. 2013;88(3):179–184. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elstein D., Mehta A., Hughes D.A. Safety and efficacy results of switch from imiglucerase to velaglucerase alfa treatment in patients with type 1 Gaucher disease. Am. J. Hematol. 2015;90(7):592–597. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ida H., Tanaka A., Matsubayashi T. A multicenter, open-label extension study of velaglucerase alfa in Japanese patients with Gaucher disease: results after a cumulative treatment period of 24months. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2016;59:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zimran A., Wajnrajch M., Hernandez B., Pastores G.M. Taliglucerase alfa: safety and efficacy across 6 clinical studies in adults and children with Gaucher disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018;13(1) doi: 10.1186/s13023-018-0776-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mistry P.K., Lukina E., Ben Turkia H. Outcomes after 18 months of eliglustat therapy in treatment-naïve adults with Gaucher disease type 1: the phase 3 ENGAGE trial. Am. J. Hematol. 2017;92(11):1170–1176. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adar T., Ilan Y., Elstein D., Zimran A. Liver involvement in Gaucher disease - Review and clinical approach. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2016;68:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nascimbeni F., Dalla Salda A., Carubbi F. Energy balance, glucose and lipid metabolism, cardiovascular risk and liver disease burden in adult patients with type 1 Gaucher disease. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2016;68:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2016.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nascimbeni F., Cassinerio E., Dalla Salda A. Prevalence and predictors of liver fibrosis evaluated by vibration controlled transient elastography in type 1 Gaucher disease. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2018;125(1-2):64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2018.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serai S.D., Naidu A.P., Andrew Burrow T., Prada C.E., Xanthakos S., Towbin A.J. Correlating liver stiffness with disease severity scoring system (DS3) values in Gaucher disease type 1 (GD1) patients. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2018;123(3):357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2017.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frenette C.T., Isaacson A.J., Bargellini I., Saab S., Singal A.G. A practical guideline for hepatocellular carcinoma screening in patients at risk. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2019;3(3):302–310. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2019.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Figueiredo FdA. In: Fireman MAdA. PCDT - Protocolo de Diretrizes Clínicas e Terapêuticas para Doença de Gaucher. Md Saúde., editor. 2017. pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vairo F., Alegra T., Dornelles A., Mittelstadt S., Netto C.B., Schwartz I.V. Hyperimmunoglobulinemia in pediatric Gaucher patients in Southern Brazil. Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 2012;59(2):339. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koppe T., Doneda D., Siebert M. The prognostic value of the serum ferritin in a southern Brazilian cohort of patients with Gaucher disease. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2016;39(1):30–34. doi: 10.1590/1678-4685-GMB-2015-0125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Starosta R.T., Pinto E., Vairo F., Dornelles A.D., Cerski C.T.S., Álvares-da-Silva M.R., Schwartz I.V.D. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Gaucher disease: reinforcing the proposed guidelines. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2019;74:34–36. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2018.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alústiza Echeverría J.M., Castiella A., Emparanza J.I. Quantification of iron concentration in the liver by MRI. Insights Imaging. 2012;3(2):173–180. doi: 10.1007/s13244-011-0132-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.James S.P., Stromeyer F.W., Chang C., Barranger J.A. LIver abnormalities in patients with Gaucher’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1981;80(1):126–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deugnier Y., Turlin B. Pathology of hepatic iron overload. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007;13(35):4755–4760. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i35.4755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taddei T.H., Dziura J., Chen S. High incidence of cholesterol gallstone disease in type 1 Gaucher disease: characterizing the biliary phenotype of type 1 Gaucher disease. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2010;33(3):291–300. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9070-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murugesan V., Chuang W.L., Liu J. Glucosylsphingosine is a key biomarker of Gaucher disease. Am. J. Hematol. 2016;91(11):1082–1089. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lukas J., Cozma C., Yang F. Glucosylsphingosine causes Hematological and visceral changes in mice-evidence for a pathophysiological role in Gaucher Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18(10) doi: 10.3390/ijms18102192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gouaze-Andersson V., Cabot M.C. Glycosphingolipids and drug resistance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1758(12):2096–2103. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neumann J., Rose-Sperling D., Hellmich U.A. Diverse relations between ABC transporters and lipids: an overview. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2017;1859(4):605–618. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pires M.M., Emmert D.M., Chmielewski J.A., Hrycyna C.A. ABCB1 and ABCG2: deciphering the role of human efflux proteins in cellular and tissue permeability. In: Linton K.J., Holland B., editors. The ABC Transporters of Human Physiology and Disease. First ed. Vol. 1. World Scientific; Singapore: 2011. pp. 94–103. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pentchev P.G., Gal A.E., Wong R. Biliary excretion of glycolipid in induced or inherited glucosylceramide lipidosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1981;665(3):615–618. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(81)90279-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lefebvre T., Reihani N., Daher R. Involvement of hepcidin in iron metabolism dysregulation in Gaucher disease. Haematologica. 2018;103(4):587–596. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2017.177816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bohte A.E., van Dussen L., Akkerman E.M. Liver fibrosis in type I Gaucher disease: magnetic resonance imaging, transient elastography and parameters of iron storage. PLoS One. 2013;8(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Regenboog M., van Dussen L., Verheij J. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Gaucher disease: an international case series. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2018;41(5):819–827. doi: 10.1007/s10545-018-0142-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hadas-Halpern I., Deeb M., Abrahamov A., Zimran A., Elstein D. Gaucher disease: spectrum of sonographic findings in the liver. J. Ultrasound Med. 2010;29(5):727–733. doi: 10.7863/jum.2010.29.5.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doneda D., Netto C.B., Moulin C.C., Schwartz I.V. Effects of imiglucerase on the growth and metabolism of Gaucher disease type I patients: a systematic review. Nutr. Metab. (Lond.) 2013;10(1):34. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-10-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doneda D., Lopes A.L., Teixeira B.C., Mittelstadt S.D., Moulin C.C., Schwartz I.V. Ghrelin, leptin and adiponectin levels in Gaucher disease type I patients on enzyme replacement therapy. Clin. Nutr. 2015;34(4):727–731. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Younossi Z.M., Stepanova M., Negro F. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in lean individuals in the United States. Medicine (Baltimore) 2012;91(6):319–327. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3182779d49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoo J.J., Kim W., Kim M.Y. Recent research trends and updates on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2018;25(1):1–11. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2018.0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wattacheril J., Sanyal A.J. Lean NAFLD: an Underrecognized outlier. Curr. Hepatol. Rep. 2016;15(2):134–139. doi: 10.1007/s11901-016-0302-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sookoian S., Pirola C.J. Genetic predisposition in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2017;23(1):1–12. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2016.0109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Glass R.B., Poznanski A.K., Young S., Urban M.A. Gaucher disease of the liver: CT appearance. Pediatr. Radiol. 1987;17(5):417–418. doi: 10.1007/BF02396621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lachmann R.H., Wight D.G., Lomas D.J. Massive hepatic fibrosis in Gaucher’s disease: clinico-pathological and radiological features. QJM. 2000;93(4):237–244. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/93.4.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosenbaum H., Sidransky E. Cholelithiasis in patients with Gaucher disease. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2002;28(1):21–27. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.2001.0480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zimmermann A., Popp R.A., Al-Khzouz C. Cholelithiasis in patients with Gaucher Disease type 1: risk factors and the role of ABCG5/ABCG8 gene variants. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2016;25(4):447–455. doi: 10.15403/jgld.2014.1121.254.zim. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material