Abstract

Background

Bile duct injury (BDI) is a devastating complication following cholecystectomy. After initial management of BDI, patients stay at risk for late complications including anastomotic strictures, recurrent cholangitis, and secondary biliary cirrhosis.

Methods

We provide a comprehensive overview of current literature on the long-term outcome of BDI. Considering the availability of only limited data regarding treatment of anastomotic strictures in literature, we also retrospectively analyzed patients with anastomotic strictures following a hepaticojejunostomy (HJ) from a prospectively maintained database of 836 BDI patients.

Results

Although clinical outcomes of endoscopic, radiologic, and surgical treatment of BDI are good with success rates of around 90%, quality of life (QoL) may be impaired even after “clinically successful” treatment. Following surgical treatment, the incidence of anastomotic strictures varies from 5 to 69%, with most studies reporting incidences around 10–20%. The median time to stricture formation varies between 11 and 30 months. Long-term BDI-related mortality varies between 1.8 and 4.6%. Of 91 patients treated in our center for anastomotic strictures after HJ, 81 (89%) were treated by percutaneous balloon dilatation, with a long-term success rate of 77%. Twenty-four patients primarily or secondarily underwent surgical revision, with recurrent strictures occurring in 21%.

Conclusions

The long-term impact of BDI is considerable, both in terms of clinical outcomes and QoL. Treatment should be performed in tertiary expert centers to optimize outcomes. Patients require a long-term follow-up to detect anastomotic strictures. Strictures should initially be managed by percutaneous dilatation, with surgical revision as a next step in treatment.

Keywords: Bile duct injury, Bile leakage, Cholecystectomy, Long-term outcome, Anastomotic stricture

Introduction

Bile duct injury (BDI) is still a much feared complication following gallbladder surgery. After the introduction of laparoscopy, the initial learning curve resulted in a rise in the incidence of major BDI up to around 1–1.5% [1]. More recently reported incidences of major BDI vary between 0.08 and 0.3% [2, 3, 4]. When including “minor” BDI, reported incidences range from 0.3 to 1.5% [5, 6]. Although the risk of sustaining BDI is low, cholecystectomy is one of the most performed procedures worldwide. Resulting from this, the total number of BDI patients is still considerable. With approximately 750,000 cholecystectomies being performed in the United States annually, an estimated 2,500 patients per year are expected to be affected by a BDI [7].

The severity of BDI ranges from relatively simple leakage of the cystic duct or liver surface to complete transection or even resection of one or more bile ducts, sometimes accompanied by vascular injuries, mainly involving the right hepatic artery and right portal vein. Several classification systems exist for BDI, with the Strasberg classification with Bismuth modification being generally accepted (Table 1) [8, 9]. Treatment is often highly individualized as not only the type of injury, but also the time to detection of the injury, comorbidity, clinical condition of the patient (e.g., the presence of sepsis or peritonitis) and location of (re)admission and diagnosis confine treatment [10]. A multidisciplinary approach including hepato-pancreato-biliary surgeons, gastroenterologists, and interventional radiologists is essential in order to achieve optimal outcomes [11, 12, 13]. Preferably the patient should be referred to a center with expertise in BDI [12, 14, 15].

Table 1.

The Strasberg-Bismuth classification for BDI

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| A | Cystic duct leak or leak from small ducts in the liver bed |

| B | Occlusion of an aberrant right hepatic duct |

| C | Transection without ligation of an aberrant right hepatic duct |

| D | Lateral injury to a major bile duct |

| E | Circumferential injury to a major bile duct: |

| E1 | Transection or stricture >2 cm from the hilum |

| E2 | Transection or stricture <2 cm from the hilum |

| E3 | Transection at the level of the bifurcation, without loss of contact between the left and right hepatic duct |

| E4 | Transection at the level of the bifurcation with loss of communication between the left and right hepatic duct |

| E5 | An injury of a right segmental duct combined with an E3 or E4 injury |

BDI, bile duct injury.

For a patient undergoing an elective cholecystectomy, BDI is an unexpected and devastating complication. It is associated with high morbidity and even mortality, and generally requires invasive treatment. Even type A injury, which is often classified as “minor injury,” may still lead to considerable morbidity due to persistent bile leakage and biliary sepsis [6]. For major injuries, short-term morbidity of up to 40–50% and mortality rates of 2–4% have been reported [16, 17, 18, 19]. Late complications include biliary strictures, anastomotic strictures, recurrent cholangitis, and biliary cirrhosis, which increase the burden for the patient even more. Furthermore, BDI patients show impaired quality of life (QoL), even years after cholecystectomy [20]. A BDI not only causes a major impact for the individual patient, it also is associated with increased health care demands and costs, and litigation claims [21, 22, 23].

The aim of this article is to give a comprehensive literature review of long-term outcomes and impact of BDI, in terms of clinical outcomes, QoL and medico-legal aspects. As there appeared to be limited data in literature regarding management of anastomotic strictures following Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy (HJ), we assessed the management and outcomes of anastomotic strictures using a large cohort of BDI patients from Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Methods

Literature Review

We provided a comprehensive overview of current literature on the long-term outcome of BDI following cholecystectomy. For this, we searched Pubmed, Embase and the Cochrane library using the following key words and Medical Subject Headins (MeSH) terms: “Bile Ducts/injuries” Medical Subject Headins, “BDI”, “HJ”, “biliodigestive anastomosis”, “surgical repair/reconstruction”, “long-term outcome”.

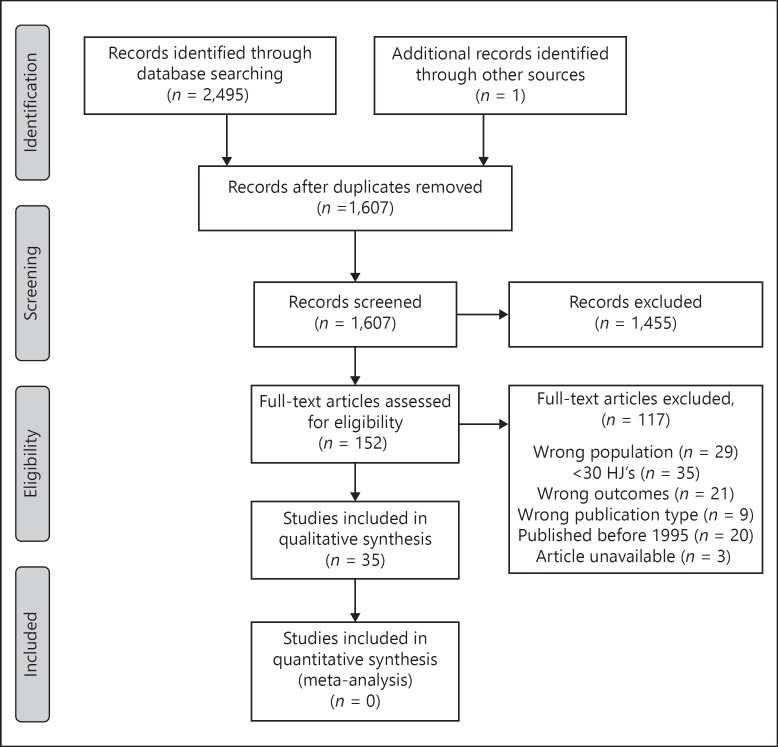

To assess reported long-term outcomes of BDI patients, we included articles reporting outcomes after endoscopic, radiologic and surgical treatment, published between 1995 and 2018. Articles reporting on less than 30 patients, articles only reporting short-term outcomes, and reviews and articles in languages other than English were excluded. For overlapping publications on the same patient cohort, the largest or most recent publication was included. Outcomes of interest were the overall long-term morbidity/mortality, incidence of anastomotic strictures, cholangitis, secondary biliary cirrhosis, incisional hernias. Records were screened in 2 phases by one author (A.M.S.), Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection process. HJ, hepaticojejunostomy.

Retrospective Analysis

As there appeared to be limited data in literature regarding the management of anastomotic strictures following HJ, we also retrospectively analyzed all patients with anastomotic strictures following a biliodigestive anastomosis from a prospectively maintained database containing a consecutive series of 836 BDI patients from the Amsterdam UMC, location AMC. All patients who developed an anastomotic stricture after Roux-en-Y HJ were identified from this database. Data of patients who developed a stricture following HJ performed in the AMC have been published before [24]. We complemented these data with (previously unpublished) information on patients referred to the AMC for the treatment of anastomotic strictures following HJ performed elsewhere.

We collected data on management of anastomotic stricture (surgically or radiologically, number of percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage [PTBD] procedures, duration of treatment) and outcomes of this treatment (recurrence of strictures and/or cholangitis, time to recurrence, development of biliary cirrhosis, long-term BDI related mortality).

Our treatment protocol has been described previously. All patients referred with a BDI were discussed in a multidisciplinary meeting including hepato-pancreato-biliary surgeons, endoscopists, and interventional radiologists to determine a treatment policy. Endoscopic, radiological, and surgical interventions were performed as previously described [25, 26, 27].

Data are presented in numbers and percentages. Means (SD) or median values with range or interquartile range are presented, when appropriate. Data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS statistics, version 24.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Clinical Outcomes after Endoscopic and Radiologic Treatment

Bile leakage due to minor injuries was usually treated endoscopically by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with sphincterotomy and/or insertion of plastic stents, which yielded success rates of 90–97% [25, 28, 29, 30]. Endoscopic treatment of more severe BDI, for example, lateral defects of major bile ducts, showed a slightly lower success rate of 85–89% [25, 29]. For biliary strictures, progressive endoscopic stenting by inserting an increasing number of plastic stents every 3–4 months was usually performed [28, 31]. The long-term success rate of this strategy is reported to be between 74 and 89% [25, 31, 32]. More proximally located injuries (Bismuth type III and IV) had a lower success rate, while the insertion of more than 1 stent increased chances of success [25].

Radiological intervention for BDI by means of PTBD is increasingly used as the availability of this technique grows. This approach is especially useful for patients with a complete transection of the bile duct (loss of continuity) but also in case of a surgically altered (upper) abdominal anatomy. PTBD may be used as a solitary treatment of BDI in patients with minor injuries, or as a bridge to definitive surgical treatment in order to optimize the clinical condition of the patient preoperatively (major injuries) [33]. PTBD in the presence of bile leakage may be more difficult as a result of non-dilated bile ducts [34] but still leads to a technical success of 90% and a (short-term) clinical success of 70–80% in expertise centers [35, 36]. PTBD in addition to surgical reconstruction yields high success rates of 98% [37, 38]. However, data on long-term outcomes of PTBD as a solitary treatment for bile leakage are very limited.

For major injuries (complete transection or resection of a bile duct) in which ERCP and PTBD fail to overcome the defect in the bile duct, a percutaneous-endoscopic rendezvous procedure can be considered before moving on to surgical reconstruction [39, 40, 41]. In a series of 47 patients from our institution, the rendezvous procedure was the final treatment with long-term success for 55% of patients, while for another 30%, the rendezvous procedure provided internal biliary drainage as a bridge to definitive surgical treatment [41].

Clinical Outcomes after Surgical Treatment

In case of a complete transection of the bile duct, surgical reconstruction is generally indicated despite the availability of the rendezvous procedure. Preferably, surgical reconstruction is performed by specialized HPB surgeons in a tertiary referral center [13, 42, 43, 44]. Perera et al. [42] compared outcomes of 45 patients treated by non-specialized surgeons to 112 patients treated by hepatobiliary specialists, showing significantly better long-term outcomes and less overall morbidity in patients treated by hepatobilary specialists (Table 2). Stewart and Way reported that only 13% of repairs performed by the index surgeon without HPB expertise were successful [43]. Of note, this was based on a selected population of patients referred to a tertiary center after undergoing HJ by the index surgeon; it was unknown how many HJs were performed by non-HPB specialists in the community. Inadequate repair of an intraoperatively detected BDI by the index surgeon may complicate the injury and lead to a worse clinical condition of the patient; several reports show that a previous attempted repair is negatively correlated with postoperative morbidity and long-term outcome [45, 46, 47]. In a few centers in the United Kingdom, the HPB surgeon travels toward the index surgeon to perform an immediate repair with excellent outcome [48].

Table 2.

Overview of reports on long-term outcomes after surgical repair of BDI by HJ

| Author | Number of HJs | Overall longterm morbidity, % | HJ stricture, % | Cholangitis, % | Intrahepatic stones, % | cirrhosis, % | Incisional hernia, % | Late BDI-related mortality, % | Time to stricture formation | Follow-up time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AbdelRafee et al. [95], 2015 | 120 | 11.6 | 14.2 | 2.5 | 6.7 | 3.3 | ||||

| Bansal et al. [96], 2015 | 138 | 8 | 54 months (6–83) | |||||||

| Booij et al. [24], 2018 | 281 | 13.2 | 7.5 | 1.8 | 30 months (IQR 9.5–51.7) | 10.5 years (IQR 6.7–14.8) | ||||

| Cho et al. [97], 2015 | 122 | 4.1 | 3.3 | 9 | Mean 4.6 years SD ±4.1 | |||||

| de Santibanes et al. [74], 2006 | 90 | 15 | 78 months (4–168) | |||||||

| Dominguez-Rosado et al. [50], 2016 | 586 | 22.5 | 3 | 2.1 | Mean 40.5 months | |||||

| Felekouras et al. [52], 2015 | 74 | 40.5 | 29.7 | 14.9 | ||||||

| Frilling et al. [98], 2004 | 33 | 17.5 | 5 | 16 months (1–42.7) | ||||||

| Gazzaniga et al. [99], 2001 | 54 | 9.3 | 1.9 | Mean 5.9 years, SD ±0.3 | ||||||

| Gomes and Doctor [100], 2015 | 57 | 7 | 3.5 | 1.8 | 84 months (36–84) | |||||

| Hajjar et al. [101], 2014 | 36 | 12 | 18 months | 34 months (12–68) | ||||||

| Holte et al. [102], 2010 | 42 | 23.8 | 2.4 | 11 months (2–51) | 110 months (0–172) | |||||

| Huang et al. [70], 2014 | 94 | 18 | 0 | 65.5 months (6–120) | ||||||

| Iannelli et al. [49], 2013 | 325 | 29 | ||||||||

| Jablonska et al. [103], 2009 | 38 | 21 | ||||||||

| Jayasundara et al. [104], 2011 | 35 | 9 | 37 months (1–90) | |||||||

| Kaman et al. [69], 2006 | 48 | 20.8 | ||||||||

| Kazibudzki et al. [105], 2006 | 30 | 10 | 6.6 | 10 | (2 months – 10 years) | |||||

| Lillemoe et al. [38], 2000 | 142 | 9.2 | 55 months (11–119) | |||||||

| Lubikowski et al. [106], 2011 | 32 | 6 | 59 months (6–102) | |||||||

| Martinez-Lopez et al. [15], 2017 | 63 | 19 | 21 | |||||||

| Mishra et al. [107], 2007 | 137 | 5.6 | 2.8 | 30 months (18–80) | ||||||

| Nuzzo et al. [13], 2008 | 41 | 12 | ||||||||

| Patrono et al. [108], 2015 | 32 | 21.9 | 81 months (12–182) | |||||||

| Perera et al. [48], 2011* | 112 | 25 | 17 | 11 | 60 months (12–212) | |||||

| 45 | 82 | 69 | 33 | |||||||

| Pottakkat et al. [47], 2010 | 30 | 63 | 37 | |||||||

| Rystedt et al. [4], 2016 | 30 | 20 | 37 months (9–69) | |||||||

| Sahajpal et al. [109], 2010 | 69 | 16 | 14 | 0 | 3 | 71.5 months (0–120) | ||||

| Schmidt et al. [110], 2004 | 46 | 19.6 | 10.9 | 4.6 | 44.6 months (2–143.5) | |||||

| Stilling et al. [111], 2014 | 139 | 42 | 30 | 23 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 2.2 | 12 months (2–141) | 102 months (0–182) |

| Sulpice et al. [112], 2014 | 36 | 13 | 5 | 3 | 93 months (26–204) | |||||

| Thomson et al. [113], 2005 | 47 | 11 | 33 months (6–201) | |||||||

| Walsh et al. [19], 2007 | 84 | 30 | 13 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 4 | 13 months | Mean 67 months | ||

| Winslow et al. [63], 2009 | 112 | 5 | 4.3 years | |||||||

| Wu et al. [114], 2007 | 176 | 12.5 | 1.7 | 3.7 years (0.25–10) | ||||||

Values are presented as proportions or medians (range), unless specified otherwise.

The study by Perera et al. [48] compared outcomes of patients treated by HPB specialists (n = 112) to those of patients treated by general surgeons (n = 45). Differences between outcomes were all statistically significant (p < 0.001).

BDI, bile duct injury; HJ, hepaticojejunostomy; HPB, hepato-pancreato-biliary; IQR, interquartile range.

The timing of surgical reconstruction has been suggested to be of influence of long-term outcomes; however, this topic is currently still under debate. Several studies have concluded that an overall delay in surgical repair has a lower risk of postoperative complications compared to early repair [10, 18, 27, 49, 50]. In contrast, publications by Barauskas et al. [30], Booij et al. [24], Kirks et al. [51], and Felekouras et al. [52] all showed similar short- and long-term results for early and delayed repair. The rationale of delayed surgical repair is that it allows for adequate sepsis control, restoration of vascular damage, and optimization of the clinical condition of the patient. Deviation of bile through a PTBD (with bile replacement via a nasogastric feeding tube) in this period will stop intra-abdominal bile leakage and reduce inflammation. Furthermore, delaying surgery may allow ischemia of the bile duct to reach its final state, making sure that the anastomosis is made on an adequate level to serve as definitive repair (generally higher up to the bifurcation). On the other hand, early repair may preclude the patient from clinical deterioration in the first place. Early repair also leads to a shorter hospitalization period and lower costs [53]. An individualized approach, taking into account the type of injury, patient characteristics but in particular the clinical condition of the patient may be most advisable. Moreover, as only 20–40% of BDIs are recognized during the initial cholecystectomy, it is not always possible to choose for an early repair.

Besides the timing of surgery, a delayed referral to a tertiary center may negatively influence patient outcomes. In a series of 63 BDI patients, Martinez-Lopez et al. [54] showed that a delayed referral was associated with a higher incidence of postoperative complications, requiring more invasive procedures and prolonging recovery. Similar results have been reported by Fischer et al. [55]. A possible explanation for this may be that pre-reconstructive optimization of the patient may be better in a center with expertise in BDI and a multidisciplinary approach, in particular by experience in endoscopic and radiological drainage procedures [56].

Surgical Techniques

The Roux-en-Y HJ is considered the optimal technique for surgical repair of BDI. Although an end-to-end bile duct anastomosis is technically simple (it may be performed by the initial surgeon) and is associated with lower rates of postoperative complications compared to HJ, it almost always requires additional endoscopic dilatation or surgical treatment. In a series of 54 patients who underwent end-to-end repair (mostly in the initial hospital), 66% of patients underwent subsequent endoscopic stenting and 32% underwent an HJ [57]. Similar results have been reported by others [58, 59].

A high-level bile duct anastomosis is recommended in order to prevent anastomotic leakages and biliary strictures due to ischemia [60, 61]. Several techniques have been described to conduct this biliary-enteric anastomosis: an end-to-side anastomosis, the Hepp-Couinaud technique, incorporating both the biliary confluence and the left hepatic duct in a side-to-side anastomosis [62], and a similar side-to-side anastomosis to the right hepatic duct as proposed by Winslow et al. [63] No direct comparison has been made between these techniques; however, a side-to-side anastomosis theoretically spares more of the vascularization of the bile duct itself, also providing a wide and tension-free anastomosis.

Outcomes

Of 1,607 records screened, 35 studies reporting on long-term outcomes following HJ for BDI were identified (Fig. 1). In Table 2, we provide an overview of reported incidences of long-term outcomes after HJ. Reported incidences of anastomotic strictures vary between 4.1 and 69%, with most studies reporting incidences around 10–20%. The median time to stricture formation varied between 11 and 30 months. This means that patients who underwent HJ for BDI require a long follow-up period. In our experience, these patients should be followed-up for 3–5 years, with the assessment of cholestatic parameters every 6 months.

Results of these studies are difficult to compare due to different definitions of outcome across studies. For that purpose, an international working group of surgeons, endoscopists, and interventional radiologists recently proposed a standardized procedure of reporting outcome of BDI using outcome grades [64]. These outcome grades, ranging from A to D, are defined for surgical and non-surgical treatment and take into account the invasiveness and duration of treatment required for complications (e.g., the period of subsequent stenting after stricture formation of a HJ) as well as the final outcome. They also propose to take into account “disease-free survival” by reporting the duration of bile duct patency according to the Kaplan-Meier method (“actuarial primary patency rate”). This grading system will not only allow for adequate comparison of results between future studies but also between different treatment modalities, recognizing the different indications for those treatment options.

Several factors have been reported to be associated with worse outcomes. Vascular injury [65, 66, 67], level of injury [19, 65, 68, 69, 70], sepsis or peritonitis [24, 50, 70], postoperative bile leakage [24], and overall postoperative complications [24] are thought to be risk factors for stricture formation.

Anastomotic strictures may eventually lead to secondary biliary cirrhosis, portal hypertension, end-stage liver disease, and death. The reported incidences of biliary cirrhosis in literature are relatively low varying between 2.4 and 10.9% (Table 2); however, this is a disastrous complication. Liver transplantation is a last-resort option for patients with secondary biliary cirrhosis. Parrilla et al. [71] reported that of 7 patients who required emergency liver transplantation for acute liver failure, 2 patients died while on the waiting list, and only one patient survived past 30 days. Of a further 13 patients who underwent elective liver transplantation for secondary biliary cirrhosis, the 5-year survival rate was 68%.

For complex vasculobiliary injuries or high intrahepatic BDI, a partial liver resection may be indicated in rare situations [72]. Only 0.8–1.4% of patients require a liver resection [73, 74]. Postoperative morbidity of this procedure is considerable [73, 75], with a short-term mortality of up to 18% [73].

The rate of incisional hernias is not reported in many studies, although this late complication contributes substantially to the overall long-term morbidity. The long-term mortality after BDI is considerable: BDI-related mortality varied between 1.8 and 4.6%. Regarding all-cause mortality, Halbert et al. [76] reported an increase of 8.8% in BDI patients compared to the expected age-adjusted death rate after 20 years.

Management of Anastomotic Strictures

Following Roux-en-Y HJ, ERCP is often not possible due to the altered anatomy. Therefore, for a non-surgical approach, PTBD with balloon dilatation and internal drainage is generally applied. This usually requires 1–4 repeat dilatations and a period of biliary drainage of approximately 3 months [26]. Overall success rates of 66–76% and low procedural morbidity of 11–13% have been reported [26, 38, 77], making PTBD with balloon dilatation a suitable first step in treatment before moving on to surgical revision. Surgical revision of an HJ shows a slightly higher operative morbidity of 30–40%, but long-term results are good in approximately 90% of cases [24, 78]. A step-up approach starting with PTBD dilatation and moving on to surgical revision when PTBD fails seems advisable; however, only a few reports exist on this topic.

The AMC Experience

Of 281 patients who underwent an HJ in our institution between 1991 and 2016, 37 patients (13%) developed an anastomotic stricture [24]. Of these, 33 patients (89%) were treated by PTBD dilatation, which initially was successful in all patients. Fourteen of these 33 patients (42%) developed a recurrent stricture, requiring another PTBD treatment and finally only 4 patients (11%) eventually underwent surgical revision of their HJ.

Furthermore, 54 patients who underwent HJ at their referring hospital were referred to us for treatment of an anastomotic stricture, at a median of 29 months after HJ (range 1–261 months). Median follow-up was 13.6 years (range 2.8–25.3 years). Of these 54 patients, 5 patients directly underwent surgical revision. One patient chose conservative treatment and up to now received 5 courses of antibiotics for cholangitis. The other 48 patients underwent PTBD with balloon dilatation. In 2 patients, dilatation failed due to a tight stenosis and these patients underwent surgical revision; in 46 patients, the treatment was initially successful. Twenty-one patients developed a recurrent stricture, for which 16 patients underwent a second cycle of PTBD dilatations (5 patients underwent surgical revision). All 16 PTBD treatments were initially successful; however, 10 patients developed another recurrent stricture. A third cycle of PTBD dilatations was attempted in 5 patients, with success in 2. The remaining 8 patients eventually underwent surgical revision of the HJ.

Combining all patients with an anastomotic stricture (both after HJ performed in our institution or in a referring hospital), 91 patients were analyzed, of whom 81 underwent PTBD treatment. PTBD treatment was eventually successful in 62 out of 81 patients (77%). Per PTBD treatment cycle, a median of 3 dilatations was performed (range from 1 to 8 dilatations). Median duration of treatment was 2 months, with a range from 1 week to 5 months.

Altogether, 24 patients underwent surgical revision of an HJ. Of these, re-stricture of the anastomosis occurred in 5 patients (21%). Four of these patients underwent additional PTBD dilatation, which was successful in all; one patient who already developed secondary biliary cirrhosis underwent a second surgical revision.

Quality of Life

After the first study on QoL following BDI in 2001 by Boerma et al. [79], several reports have examined the long-term effect of BDI on health-related QoL. Although some authors claim that in the long term BDI does not affect QoL [80, 81], most studies show an impaired QoL even many years after treatment of the injury [79, 82, 83, 84, 85]. A meta-analysis performed by Landman et al. [20] in 2013 showed a long-term detrimental effect on health-related QoL for patients with BDI when compared to patients undergoing uneventful cholecystectomy. More recent reports substantiate this finding [17, 86]. Furthermore, Booij et al. [17] assessed work-related limitations, finding a loss of productivity in paid and unpaid work and increased use of disability benefits.

Conflicting reports exist on whether QoL improves over time. De Reuver et al. [83] following up on a previous study, showed that QoL did not improve at follow-up 5.5 years later [79], while Dominguez-Rosado et al. [87] found an improvement of QoL at 5 years after the injury compared to the QoL at 1 year after the injury.

Several factors have been suggested to influence QoL in BDI patients - first, the time to detection of the injury. Surveying 107 BDI patients, Rystedt and Montgomery found that intraoperative detection and immediate intraoperative repair of an injury led to a QoL comparable to that of a matched control group of patients undergoing uneventful cholecystectomy [88]. Of note, the patients in this study mainly sustained minor injuries. Second, being involved in a malpractice litigation claim has been showed to negatively affect QoL [83, 84, 85]. In the study by de Reuver et al. [83] not only the involvement in a malpractice litigation claim but also the outcome of this litigation claim showed to be correlated to QoL.

The effect of BDI on QoL is most evident in the psychological domain [20]. This may reflect the psychological impact an unexpected and severe complication after elective surgery can have. It may also explain why there seems to be no evident correlation between clinical outcomes and QoL [87]. Remarkably, the type of injury, type of treatment (surgical/endoscopical/radiological), and duration of treatment were also not correlated to QoL according to de Reuver et al. [83].

Medicolegal Aspects

Medical liability is often a concern of surgeons involved in BDI cases. In Europe, approximately 19–32% of BDI patients are involved in a litigation claim [42, 83]. Although in the majority of claims liability is rejected, payouts are high (especially in the United States) and increasing in recent years. Reported monetary compensation varies from 2,500 to 216,000 pound in the United Kingdom, EUR 9826–55,301 in the Netherlands, and USD 628,138–2,891,421 in the United States [89].

Death as a consequence of BDI and loss of workability are associated with increased acknowledgement of liability [90, 91]. Patients with more severe (vascular) injury, with (perceived) incomplete recovery and patients with a delayed recognition of BDI are more likely to file a claim [42, 92]. Two studies also reported treatment of BDI by the index surgeon as a risk factor for litigation [42, 90], which may be another argument for treatment of these patients in tertiary expert centers.

Although the risk of BDI during cholecystectomy is currently low (0.1–0.3%), the severity of this complication requires that it be part of preoperative informed consent. However, in a survey by McManus and Wheatley [93], almost half of surgeons in the United Kingdom discussed BDI rarely or never preoperatively, and in a study by de Reuver et al. [90] the possibility of BDI was noted only in 9.7% of patient files as part of an informed consent. In a study by Perera et al. [42], among patients with BDI, 70% of patients felt that they had been inadequately informed prior to the cholecystectomy. Straightforward and honest information/communication once the damage has been detected is at least as important. Disclosure of an iatrogenic injury may be the most challenging type of bad news to deliver to a patient, and physicians are often insufficiently trained in this kind of communication [94].

Key Messages

Although clinical outcomes of endoscopic, radiologic, and surgical treatment of BDI are good with success rates of around 90%, QoL may be impaired even after “clinically successful” treatment of BDI. Clear communication between patients and health care providers is key, both preoperatively during the informed consent procedure for cholecystectomy and postoperatively after detection of the DBI.

Patients should be referred to a tertiary referral center with expertise in BDI, and treatment policy should be decided in a multidisciplinary team before intervention. For patients requiring surgical treatment, a Roux-en-Y HJ is recommended. Timing of surgery is mainly dependent on the patient condition. HJ strictures will occur in 10–20% of patients. As most strictures develop after 1 year or more, a long follow-up period or adequate instruction of patients is necessary; a follow-up period of 3–5 years, with assessment of cholestatic parameters every 6 months is recommended. Management of anastomotic strictures by PTBD yields reasonable results, with surgical revision as a next step in treatment.

Ethics Statement

The authors have no ethical conflicts to disclose.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Calvete J, Sabater L, Camps B, Verdu A, Gomez-Portilla A, Martin J, et al. Bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: myth or reality of the learning curve? Surg Endosc. 2000;14:608–611. doi: 10.1007/s004640000103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halbert C, Pagkratis S, Yang J, Meng Z, Altieri MS, Parikh P, et al. Beyond the learning curve incidence of bile duct injuries following laparoscopic cholecystectomy normalize to open in the modern era. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:2239–2243. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4485-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mangieri CW, Hendren BP, Strode MA, Bandera BC, Faler BJ. Bile duct injuries (BDI) in the advanced laparoscopic cholecystectomy era. Surg Endosc. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s00464-018-6333-7. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rystedt J, Lindell G, Montgomery A. Bile duct injuries associated with 55,134 cholecystectomies: treatment and outcome from a National perspective. World J Surg. 2016;40:73–80. doi: 10.1007/s00268-015-3281-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tornqvist B, Stromberg C, Persson G, Nilsson M. Effect of intended intraoperative cholangiography and early detection of bile duct injury on survival after cholecystectomy: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2012;345:e6457. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Booij KA, de Reuver PR, Yap K, van Dieren S, van Delden OM, Rauws EA, et al. Morbidity and mortality after minor bile duct injury following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Endoscopy. 2015;47:40–46. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1390908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flum DR, Dellinger EP, Cheadle A, Chan L, Koepsell T. Intraoperative cholangiography and risk of common bile duct injury during cholecystectomy. JAMA. 2003;289:1639–1644. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.13.1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strasberg SM, Hertl M, Soper NJ. An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180:101–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bismuth H, Majno PE. Biliary strictures: classification based on the principles of surgical treatment. World J Surg. 2001;25:1241–1244. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kapoor VK. Bile duct injury repair: when? what? who? J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:476–479. doi: 10.1007/s00534-007-1220-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Reuver PR, Rauws EA, Bruno MJ, Lameris JS, Busch OR, van Gulik TM, et al. Survival in bile duct injury patients after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a multidisciplinary approach of gastroenterologists, radiologists, and surgeons. Surgery. 2007;142:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rauws EA, Gouma DJ. Endoscopic and surgical management of bile duct injury after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;18:829–846. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nuzzo G, Giuliante F, Giovannini I, Murazio M, D'Acapito F, Ardito F, et al. Advantages of multidisciplinary management of bile duct injuries occurring during cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 2008;195:763–769. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flum DR, Cheadle A, Prela C, Dellinger EP, Chan L. Bile duct injury during cholecystectomy and survival in medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2003;290:2168–2173. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.16.2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez-Lopez S, Upasani V, Pandanaboyana S, Attia M, Toogood G, Lodge P, et al. Delayed referral to specialist centre increases morbidity in patients with bile duct injury (BDI) after laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) Int J Surg. 2017;44:82–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sicklick JK, Camp MS, Lillemoe KD, Melton GB, Yeo CJ, Campbell KA, et al. Surgical management of bile duct injuries sustained during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: perioperative results in 200 patients. Ann Surg. 2005;241:786–792. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000161029.27410.71. discussion 93–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Booij KAC, de Reuver PR, van Dieren S, van Delden OM, Rauws EA, Busch OR, et al. Long-term impact of bile duct injury on morbidity, mortality, quality of life, and work related limitations. Ann Surg. 2018;268:143–150. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ismael HN, Cox S, Cooper A, Narula N, Aloia T. The morbidity and mortality of hepaticojejunostomies for complex bile duct injuries: a multi-institutional analysis of risk factors and outcomes using NSQIP. HPB (Oxford) 2017;19:352–358. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walsh RM, Henderson JM, Vogt DP, Brown N. Long-term outcome of biliary reconstruction for bile duct injuries from laparoscopic cholecystectomies. Surgery. 2007;142:450–456. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.07.008. discussion 456–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landman MP, Feurer ID, Moore DE, Zaydfudim V, Pinson CW. The long-term effect of bile duct injuries on health-related quality of life: a meta-analysis. HPB (Oxford) 2013;15:252–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2012.00586.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hofmeyr S, Krige JE, Bornman PC, Beningfield SJ. A cost analysis of operative repair of major laparoscopic bile duct injuries. S Afr Med J. 2015;105:454–457. doi: 10.7196/samj.9038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Savader SJ, Lillemoe KD, Prescott CA, Winick AB, Venbrux AC, Lund GB, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy-related bile duct injuries: a health and financial disaster. Ann Surg. 1997;225:268–273. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199703000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de S V, e S, Bossens M, Parmentier Y, Gigot JF. National survey on cholecystectomy related bile duct injury - public health and financial aspects in Belgian hospitals - 1997. Acta Chir Belg. 2003;103:168–180. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2003.11679403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Booij KA, Coelen RJ, de Reuver PR, Besselink MG, van Delden OM, Rauws EA, et al. Long-term follow-up and risk factors for strictures after hepaticojejunostomy for bile duct injury: An analysis of surgical and percutaneous treatment in a tertiary center. Surgery. 2018;163:1121–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Reuver PR, Rauws EA, Vermeulen M, Dijkgraaf MG, Gouma DJ, Bruno MJ. Endoscopic treatment of post-surgical bile duct injuries: long term outcome and predictors of success. Gut. 2007;56:1599–1605. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.123596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janssen JJ, van Delden OM, van Lienden KP, Rauws EA, Busch OR, van Gulik TM, et al. Percutaneous balloon dilatation and long-term drainage as treatment of anastomotic and nonanastomotic benign biliary strictures. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2014;37:1559–1567. doi: 10.1007/s00270-014-0836-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Reuver PR, Grossmann I, Busch OR, Obertop H, van Gulik TM, Gouma DJ. Referral pattern and timing of repair are risk factors for complications after reconstructive surgery for bile duct injury. Ann Surg. 2007;245:763–770. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000252442.91839.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dumonceau JM, Tringali A, Papanikolaou IS, Blero D, Mangiavillano B, Schmidt A, et al. Endoscopic biliary stenting: indications, choice of stents, and results: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline - updated October 2017. Endoscopy. 2018;50:910–930. doi: 10.1055/a-0659-9864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adler DG, Papachristou GI, Taylor LJ, McVay T, Birch M, Francis G, et al. Clinical outcomes in patients with bile leaks treated via ERCP with regard to the timing of ERCP: a large multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:766–772. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barauskas G, Paskauskas S, Dambrauskas Z, Gulbinas A, Pundzius J. Referral pattern, management, and long-term results of laparoscopic bile duct injuries: a case series of 44 patients. Medicina (Kaunas) 2012;48:138–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Costamagna G, Pandolfi M, Mutignani M, Spada C, Perri V. Long-term results of endoscopic management of postoperative bile duct strictures with increasing numbers of stents. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:162–168. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.116876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tuvignon N, Liguory C, Ponchon T, Meduri B, Fritsch J, Sahel J, et al. Long-term follow-up after biliary stent placement for postcholecystectomy bile duct strictures: a multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2011;43:208–216. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson CM, Saad NE, Quazi RR, Darcy MD, Picus DD, Menias CO. Management of iatrogenic bile duct injuries role of the interventional radiologist. Radiographics. 2013;33:117–134. doi: 10.1148/rg.331125044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuhn JP, Busemann A, Lerch MM, Heidecke CD, Hosten N, Puls R. Percutaneous biliary drainage in patients with nondilated intrahepatic bile ducts compared with patients with dilated intrahepatic bile ducts. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:851–857. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Jong EA, Moelker A, Leertouwer T, Spronk S, Van Dijk M, van Eijck CH. Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage in patients with postsurgical bile leakage and nondilated intrahepatic bile ducts. Dig Surg. 2013;30:444–450. doi: 10.1159/000356711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eum YO, Park JK, Chun J, Lee SH, Ryu JK, Kim YT, et al. Non-surgical treatment of post-surgical bile duct injury: clinical implications and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:6924–6931. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i22.6924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Misra S, Melton GB, Geschwind JF, Venbrux AC, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD. Percutaneous management of bile duct strictures and injuries associated with laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a decade of experience. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:218–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lillemoe KD, Melton GB, Cameron JL, Pitt HA, Campbell KA, Talamini MA, et al. Postoperative bile duct strictures: management and outcome in the 1990s. Ann Surg. 2000;232:430–441. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200009000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Donatelli G, Vergeau BM, Derhy S, Dumont JL, Tuszynski T, Dhumane P, et al. Combined endoscopic and radiologic approach for complex bile duct injuries (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:855–864. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fiocca F, Salvatori FM, Fanelli F, Bruni A, Ceci V, Corona M, et al. Complete transection of the main bile duct: minimally invasive treatment with an endoscopic-radiologic rendezvous. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1393–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schreuder AM, Booij KAC, de Reuver PR, van Delden OM, van Lienden KP, Besselink MG, et al. Percutaneous-endoscopic rendezvous procedure for the management of bile duct injuries after cholecystectomy: short- and long-term outcomes. Endoscopy. 2018;50:577–587. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-123935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perera MT, Silva MA, Shah AJ, Hardstaff R, Bramhall SR, Issac J, et al. Risk factors for litigation following major transectional bile duct injury sustained at laparoscopic cholecystectomy. World J Surg. 2010;34:2635–2641. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0725-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stewart L, Way LW. Laparoscopic bile duct injuries: timing of surgical repair does not influence success rate. A multivariate analysis of factors influencing surgical outcomes. HPB (Oxford) 2009;11:516–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2009.00096.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mercado MA, Franssen B, Dominguez I, Arriola-Cabrera JC, Ramirez-Del Val F, Elnecave-Olaiz A, et al. Transition from a low to a high-volume centre for bile duct repair: changes in technique and improved outcome. HPB (Oxford) 2011;13:767–773. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2011.00356.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barros F, Fernandes RA, de Oliveira ME, Pacheco LF, Martinho JM. The influence of time referral in the treatment of iatrogenic lesions of biliary tract. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2010;37:407–412. doi: 10.1590/s0100-69912010000600006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mihaileanu F, Zaharie F, Mocan L, Iancu C, Vlad L., Management of bile duct injuries secondary to laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy The experience of a single surgical department. Chirurgia (Bucur) 2012;107:454–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pottakkat B, Vijayahari R, Prakash A, Singh RK, Behari A, Kumar A, et al. Factors predicting failure following high bilio-enteric anastomosis for post-cholecystectomy benign biliary strictures. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:1389–1394. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1241-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perera MT, Silva MA, Hegab B, Muralidharan V, Bramhall SR, Mayer AD, et al. Specialist early and immediate repair of post-laparoscopic cholecystectomy bile duct injuries is associated with an improved long-term outcome. Ann Surg. 2011;253:553–560. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318208fad3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Iannelli A, Paineau J, Hamy A, Schneck AS, Schaaf C, Gugenheim J. Primary versus delayed repair for bile duct injuries sustained during cholecystectomy: results of a survey of the Association Francaise de Chirurgie. HPB (Oxford) 2013;15:611–616. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dominguez-Rosado I, Sanford DE, Liu J, Hawkins WG, Mercado MA. Timing of surgical repair after bile duct injury impacts postoperative complications but not anastomotic patency. Ann Surg. 2016;264:544–553. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kirks RC, Barnes TE, Lorimer PD, Cochran A, Siddiqui I, Martinie JB, et al. Comparing early and delayed repair of common bile duct injury to identify clinical drivers of outcome and morbidity. HPB (Oxford) 2016;18 doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2016.06.016. 718-7-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Felekouras E, Petrou A, Neofytou K, Moris D, Dimitrokallis N, Bramis K, et al. Early or delayed intervention for bile duct injuries following laparoscopic cholecystectomy? A dilemma looking for an answer. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:104235. doi: 10.1155/2015/104235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dageforde LA, man MP, Feurer ID, Poulose B, Pinson CW, et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of early vs late reconstruction of iatrogenic bile duct injuries. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214:919–927. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martinez-Lopez S, Upasani V, anaboyana S, Attia M, Toogood G, et al. Delayed referral to specialist centre increases morbidity in patients with bile duct injury (BDI) after laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) International J Surg. 2017;44:82–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fischer CP, Fahy BN, Aloia TA, Bass BL, Gaber AO, Ghobrial RM. Timing of referral impacts surgical outcomes in patients undergoing repair of bile duct injuries. HPB (Oxford) 2009;11:32–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2008.00002.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nuzzo G, Giuliante F, Giovannini I, Murazio M, D&Acapito F, Ardito F, et al. Advantages of multidisciplinary management of bile duct injuries occurring during cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 2008;195:763–769. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Reuver PR, Busch OR, Rauws EA, Lameris JS, van Gulik TM, Gouma DJ. Long-term results of a primary end-to-end anastomosis in peroperative detected bile duct injury. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:296–302. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0087-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hart RS, Passi RB, Wall WJ. Long-term outcome after repair of major bile duct injury created during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Hpb. 2000;2:325–332. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Andren-Sandberg A, Johansson S, Bengmark S. Accidental lesions of the common bile duct at cholecystectomy. II. Results of treatment. Ann Surg. 1985;201:452–455. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198504000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mercado MA, Chan C, Orozco H, Tielve M, Hinojosa CA. Acute bile duct injury. The need for a high repair. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1351–1355. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-8705-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mercado MA, Chan C, Salgado-Nesme N, Lopez-Rosales F. Intrahepatic repair of bile duct injuries. A comparative study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:364–368. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0428-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hepp J, Couinaud C. [Approach to and use of the left hepatic duct in reparation of the common bile duct] Presse Med. 1956;64:947–948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Winslow ER, Fialkowski EA, Linehan DC, Hawkins WG, Picus DD, Strasberg SM. “Sideways”: results of repair of biliary injuries using a policy of side-to-side hepatico-jejunostomy. Ann Surg. 2009;249:426–434. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31819a6b2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cho JY, Baron TH, Carr-Locke DL, Chapman WC, Costamagna G, de Santibanes E, et al. Proposed standards for reporting outcomes of treating biliary injuries. HPB (Oxford) 2018;20:370–378. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2017.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bansal VK, Krishna A, Misra MC, Prakash P, Kumar S, Rajan K, et al. Factors affecting short-term and long-term outcomes after bilioenteric reconstruction for post-cholecystectomy bile duct injury: experience at a tertiary care centre. Indian J surg. 2015;77((suppl 2)):472–479. doi: 10.1007/s12262-013-0880-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schmidt SC, Langrehr JM, Hintze RE, Neuhaus P. Long-term results and risk factors influencing outcome of major bile duct injuries following cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2005;92:76–82. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Strasberg SM, Helton WS. An analytical review of vasculobiliary injury in laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy. HPB (Oxford) 2011;13:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2010.00225.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Moossa AR, Mayer AD, Stabile B. Iatrogenic injury to the bile duct. Who, how, where? Arch Surg. 1990;125:1028–1030. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1990.01410200092014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kaman L, Sanyal S, Behera A, Singh R, Katariya RN. Comparison of major bile duct injuries following laparoscopic cholecystectomy and open cholecystectomy. ANZ J Surg. 76:788–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2006.03868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang Q, Yao HH, Shao F, Wang C, Hu YG, Hu S, et al. Analysis of risk factors for postoperative complication of repair of bile duct injury after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:3085–3091. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Parrilla P, Robles R, Varo E, Jimenez C, Sanchez-Cabus S, Pareja E, et al. Liver transplantation for bile duct injury after open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2014;101:63–68. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lichtenstein S, Moorman DW, Malatesta JQ, Martin MF. The role of hepatic resection in the management of bile duct injuries following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am Surg. 2000;66:372–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Booij KA, Rutgers ML, de Reuver PR, van Gulik TM, Busch OR, Gouma DJ. Partial liver resection because of bile duct injury. Dig Surg. 2013;30:434–438. doi: 10.1159/000356455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.de Santibanes E, Palavecino M, Ardiles V, Pekolj J. Bile duct injuries: management of late complications. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1648–1653. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-0491-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pekolj J, Yanzon A, Dietrich A, Del Valle G, Ardiles V, de Santibanes E. Major liver resection as definitive treatment in post-cholecystectomy common bile duct injuries. World J Surg. 2015;39:1216–1223. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2933-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Halbert C, Altieri MS, Yang J, Meng Z, Chen H, Talamini M, et al. Long-term outcomes of patients with common bile duct injury following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:4294–4299. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-4745-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lee AY, Gregorius J, Kerlan RK, Jr, Gordon RL, Fidelman N. Percutaneous transhepatic balloon dilation of biliary-enteric anastomotic strictures after surgical repair of iatrogenic bile duct injuries. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46478. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stilling NM, Fristrup C, Wettergren A, Ugianskis A, Nygaard J, Holte K, et al. Long-term outcome after early repair of iatrogenic bile duct injury. a national Danish multicentre study. HPB (Oxford) 2015;17:394–400. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Boerma D, Rauws EA, Keulemans YC, Bergman JJ, Obertop H, Huibregtse K, et al. Impaired quality of life 5 years after bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective analysis. Ann Surg. 2001;234:750–757. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200112000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hogan AM, Hoti E, Winter DC, Ridgway PF, Maguire D, Geoghegan JG, et al. Quality of life after iatrogenic bile duct injury: a case control study. Ann Surg. 2009;249:292–295. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318195c50c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sarmiento JM, Farnell MB, Nagorney DM, Hodge DO, Harrington JR. Quality-of-life assessment of surgical reconstruction after laparoscopic cholecystectomy-induced bile duct injuries: what happens at 5 years and beyond? Arch Surg. 2004;139:483–488. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.5.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.de Reuver PR, Sprangers MA, Gouma DJ. Quality of life in bile duct injury patients. Ann Surg. 2007;246:161–163. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318070cb1e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.de Reuver PR, Sprangers MA, Rauws EA, Lameris JS, Busch OR, van Gulik TM, et al. Impact of bile duct injury after laparoscopic cholecystectomy on quality of life: a longitudinal study after multidisciplinary treatment. Endoscopy. 2008;40:637–643. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1077444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Melton GB, Lillemoe KD, Cameron JL, Sauter PA, Coleman J, Yeo CJ. Major bile duct injuries associated with laparoscopic cholecystectomy: effect of surgical repair on quality of life. Ann Surg. 2002;235:888–895. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200206000-00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Moore DE, Feurer ID, Holzman MD, Wudel LJ, Strickland C, Gorden DL, et al. Long-term detrimental effect of bile duct injury on health-related quality of life. Arch Surg. 2004;139:476–481. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.5.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Flores-Rangel GA, Chapa-Azuela O, Rosales AJ, Roca-Vasquez C, Bohm-Gonzalez ST. Quality of life in patients with background of iatrogenic bile duct injury. World J Surg. 2018;42:2987–2991. doi: 10.1007/s00268-018-4564-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dominguez-Rosado I, Mercado MA, Kauffman C, Ramirez-del Val F, Elnecave-Olaiz A, Zamora-Valdes D. Quality of life in bile duct injury: 1-, 5-, and 10-year outcomes after surgical repair. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:2089–2094. doi: 10.1007/s11605-014-2671-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rystedt JM, Montgomery AK. Quality-of-life after bile duct injury: intraoperative detection is crucial. A national case-control study. HPB (Oxford) 2016;18:1010–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hariharan D, Psaltis E, Scholefield JH, Lobo DN. Quality of life and medico-legal implications following iatrogenic bile duct injuries. World J Surg. 2017;41:90–99. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3677-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.de Reuver PR, Wind J, Cremers JE, Busch OR, van Gulik TM, Gouma DJ. Litigation after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: an evaluation of the Dutch arbitration system for medical malpractice. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kern KA. Malpractice litigation involving laparoscopic cholecystectomy. cost, cause, and consequences. Arch Surg. 1997;132:392–397. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430280066009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Alkhaffaf B, Decadt B. 15 years of litigation following laparoscopic cholecystectomy in England. Ann Surg. 2010;251:682–685. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181cc99fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.McManus PL, Wheatley KE. Consent and complications: risk disclosure varies widely between individual surgeons. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2003;85:79–82. doi: 10.1308/003588403321219812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Barrios L, Tsuda S, Derevianko A, Barnett S, Moorman D, Cao CL, et al. Framing family conversation after early diagnosis of iatrogenic injury and incidental findings. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2535–2542. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0450-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.AbdelRafee A, El-Shobari M, Askar W, Sultan AM, El Nakeeb A. Long-term follow-up of 120 patients after hepaticojejunostomy for treatment of post-cholecystectomy bile duct injuries: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 18:205–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bansal VK, Krishna A, Misra MC, Prakash P, Kumar S, Rajan K, et al. Factors affecting short-term and long-term outcomes after bilioenteric reconstruction for post-cholecystectomy bile duct injury: experience at a tertiary care centre. Indian J Surg. 2015;77((Suppl 2)):472–479. doi: 10.1007/s12262-013-0880-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cho JY, Jaeger AR, Sanford DE, Fields RC, Strasberg SM. Proposal for standardized tabular reporting of observational surgical studies illustrated in a study on primary repair of bile duct injuries. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221:678–688. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Frilling A, Li J, Weber F, Fruhauf NR, Engel J, Beckebaum S, et al. Major bile duct injuries after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a tertiary center experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:679–685. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gazzaniga GM, Filauro M, Mori L. Surgical treatment of iatrogenic lesions of the proximal common bile duct. World J Surg. 2001;25:1254–1259. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gomes RM, Doctor NH. Predictors of outcome after reconstructive hepatico-jejunostomy for post cholecystectomy bile duct injuries. Trop Gastroenterol. 2015;36:229–235. doi: 10.7869/tg.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hajjar NA, Tomus C, Mocan L, Mocan T, Graur F, Iancu C, et al. Management of bile duct injuries following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: long-term outcome and risk factors infuencing biliary reconstruction. Chirurgia (Bucur) 2014;109:493–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Holte K, Bardram L, Wettergren A, Rasmussen A. Reconstruction of major bile duct injuries after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Dan Med Bull. 2010;57:A4135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Jablonska B, Lampe P, Olakowski M, Gorka Z, Lekstan A, Gruszka T. Hepaticojejunostomy vs. end-to-end biliary reconstructions in the treatment of iatrogenic bile duct injuries. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1084–1093. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0841-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jayasundara JA, de Silva WM, Pathirana AA. Changing clinical profile, management strategies and outcome of patients with biliary tract injuries at a tertiary care center in Sri Lanka. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2011;10:526–532. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(11)60089-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kazibudzki M, Orawczyk T, Urbanek T, Kuczmik W, Ludyga T, Krupowies A, et al. Iatrogenic trauma of the biliary tract - Own experience. [Polish, English]. Chirurgia Polska. 2006;8:243–251. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lubikowski J, Post M, Bialek A, Kordowski J, Milkiewicz P, Wojcicki M. Surgical management and outcome of bile duct injuries following cholecystectomy: a single-center experience. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2011;396:699–707. doi: 10.1007/s00423-011-0745-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mishra PK, Saluja SS, Nayeem M, Sharma BC, Patil N. Bile duct injury-from injury to repair: an analysis of management and outcome. Indian J Surg. 2015;77((suppl 2)):536–542. doi: 10.1007/s12262-013-0915-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Patrono D, Benvenga R, Colli F, Baroffio P, Romagnoli R, Salizzoni M. Surgical management of post-cholecystectomy bile duct injuries: referral patterns and factors influencing early and long-term outcome. Updates Surg. 2015;67:283–291. doi: 10.1007/s13304-015-0311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sahajpal AK, Chow SC, Dixon E, Greig PD, Gallinger S, Wei AC. Bile duct injuries associated with laparoscopic cholecystectomy: timing of repair and long-term outcomes. Arch Surg. 2010;145:757–763. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Schmidt SC, Settmacher U, Langrehr JM, Neuhaus P. Management and outcome of patients with combined bile duct and hepatic arterial injuries after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surgery. 2004;135:613–618. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2003.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Stilling NM, Fristrup C, Wettergren A, Ugianskis A, Nygaard J, Holte K, et al. Long-term outcome after early repair of iatrogenic bile duct injury. a national Danish multicentre study. HPB (Oxford) 2015;17:394–400. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sulpice L, Garnier S, Rayar M, Meunier B, Boudjema K. Biliary cirrhosis and sepsis are two risk factors of failure after surgical repair of major bile duct injury post-laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2014;399:601–608. doi: 10.1007/s00423-014-1205-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Thomson BN, Parks RW, Madhavan KK, Wigmore SJ, Garden OJ. Early specialist repair of biliary injury. Br J Surg. 2006;93:216–220. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wu JS, Peng C, Mao XH, Lv P. Bile duct injuries associated with laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy: sixteen-year experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2374–2378. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i16.2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]