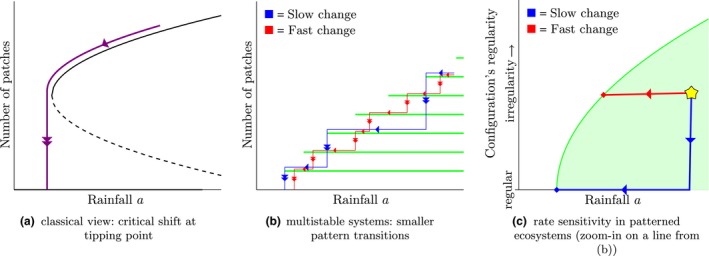

Figure 1.

Differences between classical views on ecosystem resilience and resilience in patterned ecosystems. Classically, a change in environmental conditions corresponds to a minor adjustment of the ecosystem state, until changes drive the system over a tipping point and a critical shift occurs (a). In multistable systems, every set of environmental conditions allows for multiple patterned states (b); here, instead of one critical shift, multiple smaller pattern transitions from one patterned state to another occur – that have minor impact on the system's function. Moreover every green line in (b) corresponds to a (fixed) number of patches in the system. However, resilience of a state is determined not only by the number of patches, but also by their configuration. In (c) a zoomed‐in sketch of one such line is given, where the green area indicates feasible configuration types for various levels of the rainfall parameter a. It is found that regular configurations – when water is distributed equally among the patches – are the most resilient, and can persist for lower rainfall values than the more irregular configurations. When environmental change drives a system state outside of the feasible region, not all patches can be maintained any longer and, as a consequence, a pattern transition occurs in which some patches wither. How many (and which) patches disappear during such transition again depends on the type of configuration: regular patterns typically lose half their patches (i.e. a period doubling), whereas irregular patterns lose only one (the weakest patch). Moreover – and very importantly in patterned ecosystems – the patches in a pattern are not static; on the contrary, patches slowly try to rearrange themselves into a regular configuration. Hence, under worsening climatic conditions two effects compete: (i) the movement of patches trying to rearrange themselves into a regular configuration and (ii) the shrinking of the feasible region due to climatic change. It depends on the rate of change which effect prevails, and as such two distinct trajectories can be identified (b and c). First, if change is slow (blue in (b and c)), patches have enough time to rearrange themselves into a regular configuration, and stay in that configuration until, for a relatively low rainfall value, a pattern transition occurs in which half of the patches disappear. The process then continues in the same way until the system has degraded into the desert state. Second, if the change is fast (red in (b and c)), patches do not have time to rearrange. Therefore the patterned state leave the feasible region relatively soon, and one patch disappears in the then occurring pattern transition. The process then repeats itself, and patches keep dying out one‐by‐one until the system is captured in the desert state.