Abstract

The astrocyte brain-type fatty acid binding protein (Fabp7) gene expression cycles globally throughout mammalian brain, and is known to regulate sleep in multiple species, including humans. The mechanisms that control circadian Fabp7 gene expression are not completely understood and may include core circadian clock components. Here we examined the circadian expression of Fabp7 mRNA in the hypothalamus of core clock gene Bmal1 knock-out (KO) mice. We observed that the circadian rhythm of Fabp7 mRNA expression is blunted, while overall Fabp7 mRNA levels are significantly higher in Bmal1 KO compared to control (C57BL/6 J) mice. We did not observe any significant changes in levels of hypothalamic mRNA expression of Fabp3 or Fabp5, two other fatty acid binding proteins expressed in mammalian brain, between Bmal1 KO and control mice. These results suggest that Fabp7 gene expression is regulated by circadian processes and may represent a molecular link controlling the circadian timing of sleep with sleep behavior.

Main text

Sleep behavior is exhibited by virtually every species studied, while the precise function of sleep remains unknown. Understanding the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms that relay sleep behavior may resolve important clues as to sleep function. Sleep is thought to be governed by two processes, a circadian system, which controls the daily timing of sleep, and a homeostatic system, which regulates sleepiness based on previous time spent awake [1, 2]. Circadian rhythms are regulated by a well-defined and phylogenetically conserved transcriptional/translational autoregulatory negative feedback loop [3], which includes the core clock gene Bmal1 [4]. Bmal1 is a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor known to heterodimerize with core circadian factors CLOCK or NPAS2 and bind to E-box elements in the promoter of downstream target genes to influence circadian their transcriptional output and behavior [5, 6]. Deletion of Bmal1 is the only single gene deletion that disrupts circadian clock function, whereas single gene deletion of other clock components only leads to attenuated circadian rhythms [7]. However, exactly how this circadian clock shapes molecular events that in turn regulate sleep behavior are not well understood.

Fatty-acid binding proteins (Fabp) comprise a family of small (~ 15 kDa) hydrophobic ligand binding carriers with high affinity for long-chain fatty-acids for intracellular transport, and are associated with metabolic, inflammatory, and energy homeostasis pathways [8, 9]. These include three that are expressed in the adult mammalian central nervous system (CNS), and are Fabp3 (H-Fabp), Fabp5 (E-Fabp), and Fabp7 (B-Fabp). Fabp3 is predominantly expressed in neurons, Fabp5 is expressed in multiple cell types, including both neurons and glia, and Fabp7 is enriched in astrocytes and neural progenitors. Fabp7 mRNA was identified as a unique transcript elevated in multiple hypothalamic brain regions of mice during the sleep phase [10], and Fabp7 is also known to regulate sleep in flies, mice, and humans [11]. Here we were interested in determining whether circadian Fabp7 mRNA expression is disrupted in mice that lack the core circadian clock gene Bmal1.

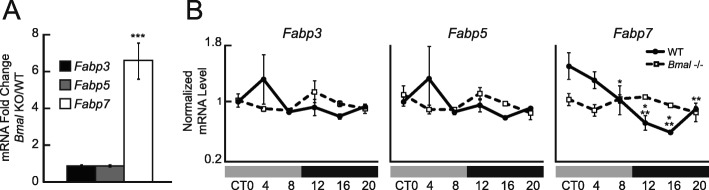

To test whether circadian Fabp7 mRNA expression is regulated by the core molecular clock, we compared Fabp7 transcript levels in hypothalamus of Bmal1 KO to wild-type (WT) littermate control C57BL/6 J mice using qPCR analysis. We observed that baseline levels of Fabp7 mRNA expression in the Bmal1 KO mouse were higher compared to WT littermate controls, irrespective of circadian time (Fig. 1a, Fig. S1), while the circadian expression of Fabp7 mRNA was completely ablated in Bmal1 KO mice compared to controls (Fig. 1b). In order to test whether other CNS expressing Fabps have altered mRNA expression as a result of Bmal1 deficiency, we profiled Fabp3 and Fabp5 and found that neither the baseline expression or circadian pattern of these transcripts were affected by Bmal1 (Fig. 1a, b), suggesting that among Fabps expressed in the CNS, both the baseline and circadian profile of transcription affected by the core clock is Fabp7 specific.

Fig. 1.

Increased baseline Fabp7 mRNA expression, and disruption of its circadian rhythm, in Bmal1 KO. (a) Average expression of hypothalamic Fabp7 mRNA is ~7fold greater in BMAL KO compared to WT mice, while Fabp3 mRNA and Fabp5 mRNA are stable (n = 18 per group). ***p < 0.001 Fabp7 mRNA KO/WT vs. Fabp3 mRNA or Fabp5 mRNA KO/WT (t-test). (b) Normalized mRNA expression values (to mean of circadian values within each group) of various Fabps depicts the circadian oscillation of Fabp7 mRNA in C57BL/6 WT which is absent in BMAL KO mice (n = 3 per group per timepoint). Fabp7 mRNA shows a significant circadian dependent change in expression based on genotype. Two-way ANOVA (p < 0.001). ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 vs ZT0 (post-hoc Bonferroni), while there is no significant difference for circadian variation of Fabp7 mRNA in BMAL KO mice

Circadian Fabp7 mRNA expression has been shown to be regulated by the nuclear hormone receptor Rev-erbα (NR1D1), a transcriptional repressor, via Rev-erbα response elements (ROREs) in the Fabp7 gene promoter [12]. Since Bmal1 deficiency greatly suppresses Rev-erbα expression, it is likely that the circadian regulation of Fabp7 mRNA by Bmal1 is through Rev-erbα. Studies determining whether Bmal1 regulates Fabp7 mRNA indirectly via Rev-erbα or whether the Fabp7 gene promoter also has functional E-box binding sites will be crucial for identifying the clock-regulated expression of this gene. Fabp7 mRNA expression was also shown to be upregulated in mice with deletion of Bmal1 in neurons and astrocytes [13]. Future studies using cell-specific knock-down of Bmal1 to determine whether disruption of core clock genes in astrocytes regulates circadian Fabp7 mRNA expression will be important for our understanding of how clock-controlled genes in non-neural cells regulate pathways affecting behavior. For example, recent studies show that astrocytes are able to regulate daily rhythms in the master circadian pacemaker of the hypothalamus, the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), and circadian behavior [14, 15]. Further, post-transcriptional processing mechanisms known to operate on Fabp7 mRNA targeting to perisynaptic processes [16] will be important to characterize following circadian clock disruption in astrocytes. Determining whether circadian Fabp7 expression is necessary for daily rhythms in SCN and extra-SCN physiology [17] and related behavior are additional avenues for future study.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank A. Pack and the UPENN Center for Sleep and Circadian Neurobiology, and G. FitzGerald and lab for the Bmal1 KO mice and helpful discussions. We would also like to thank Swetha Patel for technical assistance.

Authors’ contributions

JRG and GKP conceived and designed the experiments. JRG wrote the manuscript. GKP carried out the experiments. JRG and GKP analyzed the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Supported by NIH grant 1 U54 HL117798 and R35GM133440.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animals in this study were housed according to the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Pennsylvania. All experimental protocols were approved by IACUC.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jason R. Gerstner, Email: j.gerstner@wsu.edu

Georgios K. Paschos, Email: gpaschos@pennmedicine.upenn.edu

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13041-020-00568-7.

References

- 1.Borbely AA, Achermann P. Sleep homeostasis and models of sleep regulation. J Biol Rhythm. 1999;14:557–568. doi: 10.1177/074873099129000894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borbely AA, Daan S, Wirz-Justice A, Deboer T. The two-process model of sleep regulation: a reappraisal. J Sleep Res. 2016;25:131–143. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allada R, Emery P, Takahashi JS, Rosbash M. Stopping time: the genetics of fly and mouse circadian clocks. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:1091–1119. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buhr Ethan D., Takahashi Joseph S. Circadian Clocks. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2013. Molecular Components of the Mammalian Circadian Clock; pp. 3–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albrecht U. Timing to perfection: the biology of central and peripheral circadian clocks. Neuron. 2012;74:246–260. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohawk JA, Green CB, Takahashi JS. Central and peripheral circadian clocks in mammals. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2012;35:445–462. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu AC, et al. Intercellular coupling confers robustness against mutations in the SCN circadian clock network. Cell. 2007;129:605–616. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furuhashi M, Hotamisligil GS. Fatty acid-binding proteins: role in metabolic diseases and potential as drug targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:489–503. doi: 10.1038/nrd2589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Storch J, Corsico B. The emerging functions and mechanisms of mammalian fatty acid-binding proteins. Annu Rev Nutr. 2008;28:73–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.27.061406.093710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerstner JR, Vander Heyden WM, Lavaute TM, Landry CF. Profiles of novel diurnally regulated genes in mouse hypothalamus: expression analysis of the cysteine and histidine-rich domain-containing, zinc-binding protein 1, the fatty acid-binding protein 7 and the GTPase, ras-like family member 11b. Neurosci. 2006;139:1435–1448. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerstner JR, et al. Normal sleep requires the astrocyte brain-type fatty acid binding protein FABP7. Sci Adv. 2017;3:e1602663. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1602663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schnell A, et al. The nuclear receptor REV-ERBalpha regulates Fabp7 and modulates adult hippocampal neurogenesis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lananna BV, et al. Cell-Autonomous Regulation of Astrocyte Activation by the Circadian Clock Protein BMAL1. Cell Rep. 2018;25:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tso CF, et al. Astrocytes regulate daily rhythms in the Suprachiasmatic nucleus and behavior. Curr Biol. 2017;27:1055–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brancaccio M, et al. Cell-autonomous clock of astrocytes drives circadian behavior in mammals. Sci. 2019;363:187–192. doi: 10.1126/science.aat4104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerstner JR, et al. Time of day regulates subcellular trafficking, tripartite synaptic localization, and polyadenylation of the astrocytic Fabp7 mRNA. J Neurosci. 2012;32:1383–1394. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3228-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paul Jodi R., Davis Jennifer A., Goode Lacy K., Becker Bryan K., Fusilier Allison, Meador‐Woodruff Aidan, Gamble Karen L. Circadian regulation of membrane physiology in neural oscillators throughout the brain. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2019;51(1):109–138. doi: 10.1111/ejn.14343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.