Abstract

Minimal residual disease (MRD) analysis for patients of acute leukemia has evolved as a significant prognostic factor. Based on the MRD results, the cases are risk-stratified after induction chemotherapy, and an alteration in further management is made to yield maximal therapeutic benefits. The two primary methodologies for MRD detection are multi-parameter flow cytometry (MFC) and polymerase chain reaction. MFC identifies the MRD based on characteristic ‘leukemia-associated immunophenotypes’ on the residual leukemia cells. MRD analysis by MFC is most frequently done at the post-induction stage of treatment and often can achieve a sensitivity of detecting one leukemic cell in 10,000 normal cells, or even higher at times. This review outlines the technical aspects and provides inputs on standard antibody panels used for MRD detection in B-, T-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemias, and acute myeloid leukemia.

Keywords: Minimal residual disease (MRD), Multi-parameter flow cytometry (MFC), Immunophenotyping

Introduction

Acute leukemia is a heterogeneous neoplasm and encompasses the four broad subcategories viz. acute myeloid leukemia (AML), B- acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), T- acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) and acute leukemias of ambiguous lineage, as per the updated 2016 World Health Organisation (WHO) classification of hematological malignancies [1]. All these subcategories have further been ramified into numerous subtypes based on various immunophenotypic and molecular markers. Each sub-category of acute leukemia is managed differently, as per the current standard guidelines [2, 3]. Even with the advent of various new therapeutic approaches and refinements in the treatment protocols, these malignancies can relapse after a good initial response. The main reason behind this is the ‘minimal residual disease’ (MRD), defined by the presence of leukemic cells in a patient which escapes from the morphological identification on routine light microscopy. Identification, as well as quantification of this residual disease, has evolved as a significant prognostic factor to manage acute leukemias in the current era. Based on the MRD results, the cases are risk-stratified after induction chemotherapy, and an alteration in further management is made to yield maximal therapeutic benefits [4–6].

The two primary methodologies for MRD detection are multi-parameter flow cytometry (MFC) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR). MFC identifies the MRD based on characteristic ‘leukemia-associated immunophenotypes’ (LAIPs) on the residual leukemic cells whereas PCR employs the use of specific genetic aberrations, and/or specific immunoglobulin or T cell receptor gene rearrangements [7]. Both techniques offer comparable high sensitivities [8] though have certain limitations as well. This review focuses on the MRD detection in B/T- ALL and AML cases by MFC with regards to the current strategies practiced worldwide.

Clinical Indications of MRD Testing in Acute Leukemias

A significant breakthrough in the treatment advances of acute leukemia has been the estimation of MRD in the post-induction phase. Based on the MRD results, further therapy can either be intensified or de-intensified to achieve long-term complete remission and reduces the harmful effects of toxic chemotherapies. Hence, MRD has emerged as a strong prognostic factor for assigning a particular case of acute leukemia into various risk categories and treatment arms [6, 9, 10]. Another upcoming indication of MRD testing has been its role in the treatment decision making for the patients undergoing stem cell transplant (SCT). Among the ALL patients, MRD estimation before the SCT is an essential indicator of the outcomes [11–14]. Also, post-SCT, MRD estimation is a good predictor of impending relapse in such patients [15].

Clinical trials with the new therapeutic agents for acute leukemias nowadays are employing MRD at various time points to study the efficacy of these agents [16–18]. In fact, MRD has been used as an endpoint for evaluation of these agents [19].

Time Points of MRD Testing

There are differences in the MRD testing time points with regards to the type of acute leukemia; the treatment protocol received as well as for the pediatric/adult age groups. For the childhood ALL, assessment of MRD is recommended at 1 month (post-induction: day 33), 3 months (post-consolidation: day 78), after re-induction and during the first part of maintenance therapy [20]. MRD is said to be negative at a cut-off of ≤ 10−4. The time points which are most informative for prediction of relapse are at 1 month (day 33) and 3 months (day 78). Based on the MRD estimation at these time points, cases are stratified into low-risk (negative MRD at both time points), medium-risk (< 5 × 10−4 MRD at day 78) and high-risk (≥ 5 × 10−4 MRD at day 78) [7]. For the adult ALL, different study groups viz. the Programa Espanol de Tratamientos en Hematolog´ıa (PETHEMA), the Northern Italy Leukemia Group (NILG) and the French Group For Research On Adult ALL (GRAALL) used different cut-off to define MRD. Most of them however, recommends MRD testing post-induction (day 29–35) and/or after first consolidation (week 16) [7, 21]. The PETHMA group used a cut-off of 5 × 10−4 at week 16–18, the NILG group defined MRD cut-off at 10−4 (week 16 and 22) and the GRAALL at 10−4 (week 6 for Philadelphia negative ALL) and 10−3 (for high-risk patients) [7]. However, a widespread consensus over all time points of MRD detection has not been achieved.

With regards to the AML group, the timeline for MRD determination has been even less consistent among the different study groups. However, the majority of them have advocated MRD testing at the post-induction time-point [22]. This has been a robust predictor of outcome in such patients. Further, testing in other phases has been areas of research. Besides, molecular etiology of AML has also been an essential factor to dictate the time of MRD testing [23].

Principles of MRD Testing by MFC

The chronological expression of various antigens on the various series of developing cells of myeloid and lymphoid lineages is indispensable for understanding the concept of identification of MRD cells by MFC. Any deviation from this normal maturational pattern has been labelled as ‘leukemia-associated immunophenotype.’ This principle remains the mainstay of MRD assays for B-, T-, and myeloid lineage acute leukemias.

For B-ALL, MFC employs three basic immunophenotypic features which stand behind its pathogenesis and helps in identification as well as distinguishing leukemic blasts from normal maturing B-cells in bone marrow or peripheral blood sample. Firstly, there are specific antigens which are differentially expressed in leukemia cells compared to the normal maturational pattern. These can be either ‘under-/over-expressed’ and hence, stands out on a flow cytometry plot away from the normal maturing cell population. For example, overexpression of CD34 and/or CD10 and under-expression of CD45 and/or CD38 on leukemic cells have been employed as a good strategy to identify MRD [23–26] (Fig. 1). Second strategy employed for identification of MRD is called as ‘lineage-infidelity.’ There are certain markers are not expressed during normal B-cell development but are aberrantly expressed on leukemic cells. These are usually the markers of other lineages like CD13, CD33, CD117, CD15, CD65, CD56 and CD66c [25]. Thirdly, ‘asynchronicity’ of antigen expression on leukemic cells is also helpful in MRD estimation. There are markers whose expression are not expected for a particular stage of B-cell development or those with ectopic expression, hence these characterize a cell as leukemic blast, e.g., CD21 and NG2 (the corresponding antibody is 7.1) are not expressed on normal progenitor B-cells but on leukemia blasts [25]. Besides, many new markers have been studied across different studies whose altered expression can help in MRD detection (over-expression- CD86, CD49f, CD44, CD58, CD123, CD73, CD200, CD304; under-expression- CD81, CD24, CD72; aberrant expression- CD123, CD11b, CD304) [27–35].

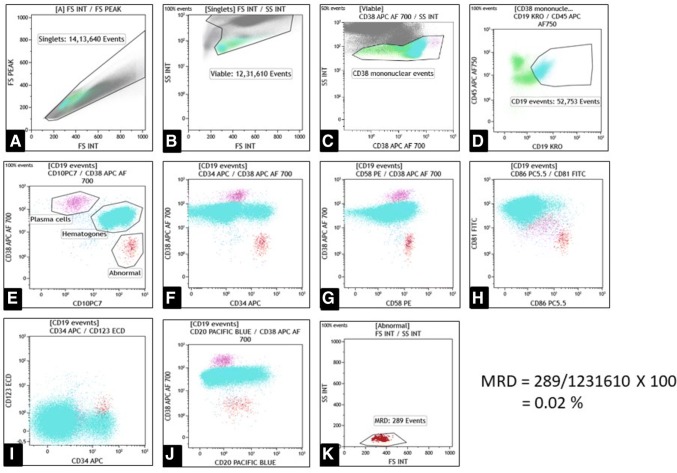

Fig. 1.

Representative plots from a case of B-Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (post-induction bone marrow aspirate). a Singlets are gated on forward scatter-area versus peak. b Viable events are then gated on forward scatter-area versus side scatter-area. c Mononuclear viable cell population is gated on CD38/side scatter plot. d CD19 positive events are then gated for further analysis. e CD38/CD10 plot is showing an abnormal cell population which is CD38dim/CD10bright compared to plasma cells and hematogones (a LAIP). The abnormal cell population is expressing CD34 (plot f), CD58 (plot g) and CD86bright/CD81neg (plot h). All these are LAIPs. There is also slight expression of CD123 (plot j) and CD20pos/CD38dim. Once, these LAIPs are recognized, the discrete cell population of abnormal cells is gated on forward and side scatter-area. The calculated MRD is shown on right

T-ALL blasts MRD identification is based on the principle that the presence of immunophenotypically immature T-cells in bone marrow/peripheral blood identifies MRD. T-ALL blasts usually display phenotypes that correspond to different stages of thymocyte development. For example, the cells co-expressing cCD3/TdT or CD7/TdT are T-ALL blasts and when detected in a sample of bone marrow/peripheral blood indicates MRD [25]. Lower expression or lack of antigen expression, like CD5, sCD3, CD2, and dual negativity of CD4 and CD8 are also beneficial in determining abnormal from normal T-cells. Over-expression of CD7 is another common finding and in addition expression of CD13/CD33 (lineage infidelity) can often be of help in MRD detection [36]. Since T-ALL blasts nearly always express CD7 and cytoplasmic-CD3, these remain essential gating markers (Fig. 2).

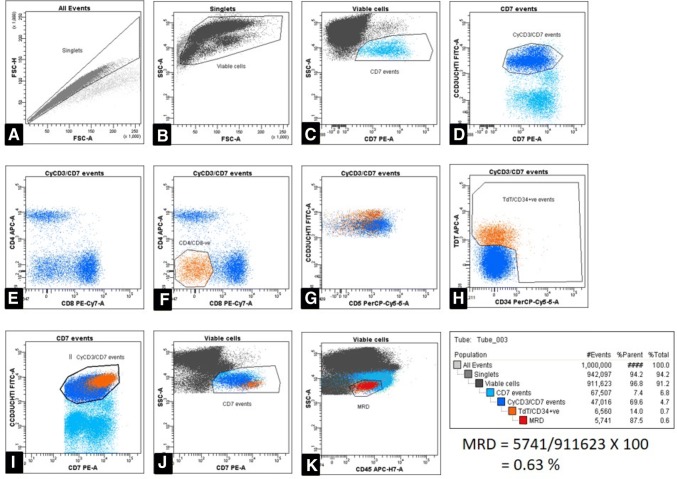

Fig. 2.

Representative plots from a case of T-Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (post-induction bone marrow aspirate). a Singlets are gated on forward scatter-area versus height. b Viable events are then gated on forward scatter-area versus side scatter-area. c Plot shows gating of viable CD7 positive cells (representing T-cells). d Finally, discrete T-cell population was gated with CD7/cCD3. NK cells are excluded based on CD16-CD56pos/CD38bright population (not shown). e On CD4/CD8 plot, some dual negative cells are present apart from normal CD4 and CD8 positive T-cells. These dual negative cells when gated (plot g) shows CD5 positivity (plot h), To note that these cells have CD5 expression dimmer than the normal T-cells (a LAIP). i Plot shows the T-cells with TdT and CD34 positivity and this abnormal population constitutes MRD, which when gated (orange) has been highlighted on CD7/cCD3 plot (plot i) with a brighter CD7 compared to normal T-cells (in blue). This population is also highlighted on CD7/SSC-A plot (k). Finally, MRD is calculated from CD45/SSC-A plot (l) as a discrete cluster. The hierarchy of all the gated cells and number of events are provided and MRD calculation is shown on right (color figure online)

However, estimation of MRD in T-ALL can be challenging in certain situations. One may encounter a case of T-ALL where the markers of immaturity are lost due to induction chemotherapy. This scenario can be seen in about 40% of such cases. To tackle this situation, defining the antigenic aberrancies are helpful in delineating MRD once the initial population of interest is gated. The altered expression of antigens like CD2, CD3, CD4, CD5, CD7, CD8 and CD45 are helpful in such cases [37]. Loss of sCD3, seen on a small subset of normal T cells also needs careful exclusion with normal expression-patterns of CD2, CD5, CD7, CD45, split amongst CD4 and CD8, presence of cCD3, and absence of any immaturity markers. NK cells should be excluded from the initial gated population as they often contaminate the MRD estimation. To ensure their exclusion from CD45bright/CD7pos cells, the dual-negativity of cCD3 and sCD3 and further the pattern of CD16pos/CD56pos and CD38bright can be useful.

For AML, same principles of cross-antigen expression, loss or over-expression, and asynchronous expression of markers govern MRD detection, though these cells are more heterogeneous for various markers and spread across multiple areas on dot plots. Hence, it remains pertinent to understand and build-up experience of normal patterns of maturation of myeloid precursors. In view of several subtypes of AML, which include variable differentiation to monocytic, erythroid and megakaryocytic lineages, it is more relevant to know diagnostic immunophenotype of AML, as compared to B- or T-ALLs. The common aberrations seen on AML cells are: (1) asynchronous expression of early/late antigens on a particular cell stage (CD34 along with CD15); (2) lineage infidelity (expression of B-/T-/NK-cell markers on AML cells viz. CD7, CD2, CD3, CD5, CD19, CD56); (3) under-/over-expression of antigens, and (4) absence of lineage-specific antigens like CD13, CD33 on the leukemia myeloid blasts [23, 38, 39] (Fig. 3). The good strategy to assess AML-MRD is by initial gating of all cells in the progenitor region defined by CD45dim with a low to intermediate side scatter. The gate is usually extended to include the monocytic region. This is followed by back gating to delineate CD34pos cells as well as CD117pos cells on a CD45/SSC plot. It should be noted that the CD117pos population is not limited to myeloblasts. It also includes promyelocytes (CD34neg/HLA-DRneg/CD33bright), early erythroid precursors (CD36bright/HLA-DRneg), mast cells (CD117bright(est)/CD33bright/HLA-DRneg) and a subset of immature NK cells (CD7bright/CD16-CD56pos/CD38bright). CD19 can be utilized to exclude normal B-cell precursors (hematogones) and also plasma cells from CD45dim gate. A care is required for not excluding CD19-expressing leukemic myeloblasts, often seen in AML with t(8;21). The normal populations of CD123bright cells should be distinctly identified in CD45dim region. This usually includes basophils (CD123bright/HLA-DRneg) and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (CD123bright/HLA-DRpos). Clear identification of different sets of normal populations in CD45dim region is necessary for discrete analysis of the target myeloblasts.

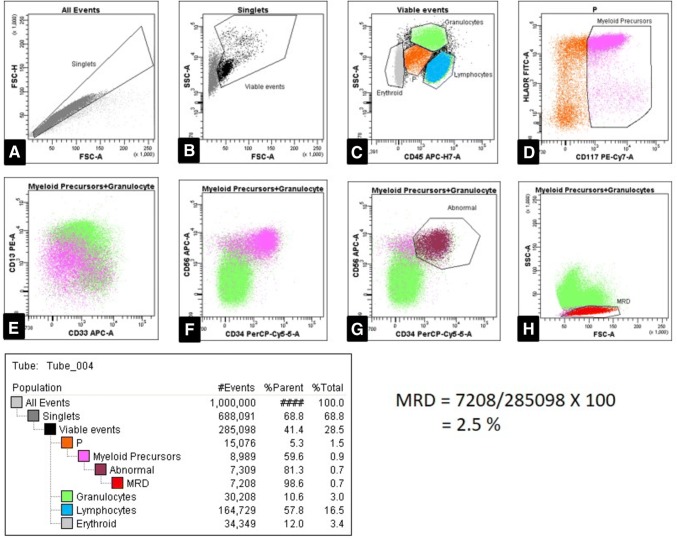

Fig. 3.

Representative plots from a case of Acute Myeloid Leukemia (post-induction bone marrow aspirate). a Singlets are gated on forward scatter-area versus height. b Viable events are then gated on forward scatter-area versus side scatter-area. c This plot shows the distribution of viable leukocytes based on CD45 expression versus side scatter-area. The cells in the precursor region, labelled as ‘P’ (low SSC-A and CD45dim) are gated for further analysis. d Plot shows gating of myeloid precursors which are CD117pos and/or HLA-DRpos. These precursors are then analysed to look for LAIPs (exclusion of normal populations in CD45dim gate, like hematogones, early erythroid precursors, mast cells, basophils, plasmacytoid dendritic cells, immature NK cells and promyelocytes is explained in the text). f Plot shows under-expression of CD13 and CD33 on myeloid precursors (in pink) compared to that of mature neutrophils (green). g Plot shows another LAIP in the form of aberrant expression of CD56 on myeloid precursors (pink) and these are also positive for CD34 (plot h). Finally, the discreet MRD population was gated on forward and side scatter-area plot for calculation (red). The hierarchy of all the gated cells and number of events are provided and MRD calculation is shown on right (color figure online)

Data from CD45dim gate and from CD34pos myeloblast gate should preferably be separately analysed. This two-step gating strategy is more reliable as analysis of CD45dim cells take care of cases with CD34neg myeloblasts, and any unusual population in CD45dim region can be looked up thoroughly for the aberrancies. CD34-gated myeloblasts are more reliable for analysing the aberrancies, and are known to be more therapy-resistant cells [40].

A new emerging concept of estimation of leukemic stem cells (LSCs) in the follow-up bone marrow samples of AML cases is a promising approach [41]. LSCs defined by CD34pos/CD38neg comprise of a population which initiates and maintains the disease. A high LSCs count has been associated with a worse outcome. This population often express various aberrancies like expression of CD25, CD32, CD44, CD47, CD96, CD123, CD133, CLL-1, TIM3, IL1RAP. These markers can be used in addition to CD34/CD38 to better delineate LSCs. Recently, Zeillemaker et al. [42] have devised a single tube method to estimate LSCs. The tube includes 8 colors viz. CD45, CD34 and CD38 as backbone markers, CD45RA, CD123, CD33 and CD44 as specific markers plus any one as aberrancy marker in the form of cocktail (CLL-1/TIM-3/CD7/CD11b/CD22/CD56).

Technical Aspects of MRD Detection

Sample Prerequisites

Many large-scale studies have confirmed that the bone marrow sample is more informative than peripheral blood for detection of MRD [43–45]. There has been a difference of 1–3 log of MRD being lower in a paired peripheral blood than a bone marrow sample [20]. The difference of residual tumor load is more apparent in B-ALL as compared to T-ALL. Bone marrow aspirate, however, remains the sample of choice for MRD detection. There have been some speculations regarding different tumor load of leukemia cells in different bone marrow compartments post-chemotherapy that might affect the correct MRD quantification. But the later studies refuted this notion. The tumor load reduction is more likely homogenous in all marrow compartment, and thus, the site of sampling of bone marrow is usually unilateral, from the posterior superior iliac spine [46].

It is advisable that the first sample of aspirate should be used for MRD studies. Care should be taken not to dilute it with peripheral blood, and usually, a 2 ml but less than 5 ml sample is sufficient to recover cells that give a sensitivity of ≤ 10−4 [7]. EDTA- or Heparin- anti-coagulated samples are good and preferably to be assayed for MRD detection within 24–48 h. Pre-titrated and cocktailed antibody-panel is preferred for more consistent results. Erythrocyte lysing step may follow antibody-incubation step or may be done prior to staining. Both procedures are known to yield satisfactory results, although prior lysing of bulk sample is good for acquisition of a large number of events or for concentrating low cellularity samples.

Instrument Requirements (Hardware and Software)

MRD detection by MFC has paralleled with the advancements in the flow cytometry technology. Upgraded ten to thirteen color instruments are now available for clinical use to rapidly identify MRD [47, 48]. The most commonly used cytometers are 6–8 colors, however, use of 10 color flow cytometer is rapidly gaining popularity with the aim to define MRD with even a limited sample volume and with more antigenic markers. The ability to rapidly acquire millions of events make these advanced instruments well suited for MRD detection. Various advanced, high-efficiency software are now available which can rapidly process the bulk amount of acquired data, do a quick post-acquisition “compensation” and display the plots and results in a simple and more understandable format [47]. With the availability of technical advancement, there is a recent trend to automate MRD analysis.

Antibody Panels

The selection of antibody panels depends definitely on the version of a flow cytometer that a laboratory is using. Numerous combinations of antibodies, comprising of four colors to ten color- cocktails have been tested. Though the gating/backbone markers for various MRD assays have been more or less consistent, preferential use of certain other markers is usually based on individual experiences. Many studies have put forward their recommendations over past two decades, and examples of recommended panels for B-/T-ALL and AML by Wood [49] and EuroFlow consortium [50] for a two laser and four laser flow cytometer are given in Table 1. For each panel, there are certain backbone markers which identify all the normal as well as leukemic cells (target population) and down further there are markers which help in separation of these two cell populations. Commonly used backbone markers for B-ALL is CD19 with side scatter, for T-ALL is CD7 with side scatter, and for AML are CD45/CD117 with side scatter.

Table 1.

Immunophenotypic panels recommended for 2/4 laser flow cytometera for B-/T-ALL and AML

| B-ALL (2 lasers) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APC | perCP | PE | FITC | |

| Tube 1 | CD19 | CD45 | CD20 | CD10 |

| Tube 2 | CD19 | CD45 | CD9 | CD34 |

| B-ALL (2 lasers) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC7 | FITC | PE | PCP5.5 | APC | APC7 | – | – | – | |

| Tube 1 | CD19 | CD20 | CD10 | CD38 | CD58 | CD45 | – | – | – |

| Tube 2 | CD19 | CD9 | CD13 + 33 | CD34 | CD10 | CD45 | – | – | – |

| B-ALL (4 laser) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC7 | FITC | PE | PCP5.5 | APC | APC7 | PB | A594 | – | |

| Tube 1 | CD19 | SYTO16 | CD10 | CD34 | CD58 | CD45 | CD20 | CD38 | – |

| B-ALL (EuroFlow antibody panel) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC7 | FITC | PE | PCP5.5 | APC | APC-A750 | PB | PO | – | |

| Tube 1 | CD19 | CD81 | CD66c + CD123 | CD34 | CD10 | CD38 | CD20 | CD45 | – |

| Tube 2 | CD19 | CD81 | CD304 + CD73 | CD34 | CD10 | CD38 | CD20 | CD45 | – |

| T-ALL (4 laser) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC7 | FITC | PE | PC5 | APC | APC7 | PB | A594 | PE-TR | |

| Tube 1 | CD5 | cCD3 | CD7 | CD56 | sCD3 | CD45 | CD16 | CD38 | – |

| Tube 2 | CD3 | CD2 | CD5 | CD56 + 16 | CD7 | CD45 | CD8 | CD4 | CD34 |

| AML (4 laser) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC7 | FITC | PE | PCX | APC | APC7 | PB | A594 | PE-TR | APC-A700 | |

| Tube 1 | CD13 | CD15 | CD33 | CD117 | CD34 | CD45 | HLA-DR | CD38 | CD19 | CD71 |

| Tube 2 | CD13 | CD64 | CD123 | CD14 | CD34 | CD45 | HLA-DR | CD38 | CD4 | CD16 |

| Tube 3 | CD33 | CD56 | CD7 | CD5 | CD34 | CD45 | HLA-DR | CD38 | – | – |

aThe two lasers used have excitation at 488 nm (FITC, PE, PCP5.5, PC7, PE-TR, PCX) and 635 nm (APC, APC7, A700). A 4 laser flow cytometer, also, have a laser with excitation at 407 (PB or V450) and 594 nm (A594). The SYTO16 dye binds to nuclei acid and helps in the enumeration of total nucleated cells

FITC fluorescein isothiocyanate, PE phycoerythrin, PCP5.5 PerCP-Cy5.5, PC7 E-Cy7, APC allophycocyanin, APC7 APC-Cy7, PB pacific blue or V450, PO pacific orange, A594 Alexa 594, PE-TR PE-Texas Red, PCX PE-Cy5 or PE-Cy5.5 or PerCP-Cy5.5, APC-A700 APC-alexa 700, APC-A750 APC-alexa 750

Once the sample is acquired on a flow cytometer, it gives a significant amount of data which needs to be appropriately channelized. The main aim of data analysis is to identify the leukemic cells from the normal cell populations as well as from the various artifacts. There are two approaches currently employed for identification of MRD. The one uses LAIPs determination at the time of diagnosis and their subsequent identification in the follow-up samples. The other approach is the construction of a standard template using normal marrow samples. Though there no definite consensus, but some reports mention to use at least 20 bone marrow samples from the cases where marrow procedure is done for conditions like immune thrombocytopenia, Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and for MRD analysis in B-ALL, to use end-induction marrow samples of T-ALL [40, 51]. The normal templates are made using these samples and the recommended antibody panels. Superimposing this template on the test samples help in identifying MRD. Both the approaches work well in our experience, and their feasibility depends on whether the same laboratory is processing the diagnostic as well as follow-up samples [24, 49].

Usually, the analysis is started by identifying the target population with the help of side scatter and a lineage-specific antigen. The gating strategy is more uniform throughout different standardized laboratories in cases of B-ALL MRD but for T-ALL and AML cases, it varies [40]. The different strategies have been described in the section on ‘principles of MRD testing by MFC.’ This gated population is further analyzed for the various antigens which may help is distinguishing MRD from the normal cells in the sample what are called as LAIPs. Identification of at least two LAIPs is recommended for the quantification of MRD. The commonly used LAIPs for the subtypes of acute leukemia are compiled in Table 2 [23, 25, 36].

Table 2.

Leukemia-associated immunophenotypes commonly employed for identification of MRD

| B-ALL | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Markers of normal B-cell development | |

| A. Under-expression | CD45, CD38, CD81, CD72, CD24 | |

| B. Over-expression | TdT, CD22, CD10, CD34, CD123, CD58, CD86, CD73, CD200 | |

| C. Asynchronous expression |

CD19/CD34bright/CD10bright CD19/CD34bright/CD21bright CD19/CD34dim/TdTbright CD19/CD34bright/cyto.μbright |

|

| 2. | Cross-lineage antigen expression |

CD13, CD33, CD15 CD65, CD56, 7.1, CD66c |

| T-ALL | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Markers of T-lineage not seen outside the thymus | TdT, CD34 |

| 2. | Asynchronous antigen expression | CD3dim/CD2dim |

| 3. | Under-/over-expression |

CD2dim/neg/CD3neg/CD7bright CD3neg/CD5dim CD4dim/CD8dim CD3neg CD5neg CD2neg |

| 4. | Cross-lineage antigen expression |

CD13 CD33 |

| AML | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Asynchronous expression of markers of normal myeloid lineage |

CD34/CD11b CD34/CD14 CD34/CD64 CD34/CD65 CD34/CD15 CD34/CD56 CD117/CD11b CD117/CD14 CD117/CD64 CD117/CD15 CD117/CD56 CD117/CD65 CD33/CD15 CD33/CD64 CD33/CD65 CD33/CD11b CD33/CD56 |

| 2. | Cross-lineage antigen expression | CD2, CD7, CD10, CD19, CD2,CD7, CD10, CD19, Glycophorin A |

| 3. | Under-/over-expression |

CD33bright/CD13neg CD33neg/CD13bright HLA-DRbright/CD13neg HLA-DRbright/CD33neg |

The quality of a particular LAIP in distinguishing leukemic cells from the normal marrow cells is determined by its sensitivity (the percentage of LAIP expression on leukemic cells; it should be expressed on > 10% blasts), specificity (the percentage of LAIP expression in normal marrow cells; it should be less than 0.1%) and stability (LAIP may undergo phenotypic shifts) [23]. The stability of LAIP may be lost during therapy specially with the steroids which often downregulates the immaturity markers on leukemic cells. Hence, a LAIP which may initially be present at the time of diagnosis may not be detected in follow-up MRD studies [49]. Thus, during the evaluation of MRD at a particular time point, it is always advisable to look for LAIP which marks a discreet population of leukemic cells from the normal and not merely by just superimposing on the LAIPs detected at the time of diagnosis.

Quality Control

The MRD testing requires strict quality control measures. The number of events to be acquired are dictated by the sensitivity of the assay. By using a serial dilution assay with the leukemic cells to the normal marrow cells, it has been shown that MFC can reliably measure MRD to a level of 10−4 [39]. To achieve a sensitivity of at least 10−4, one should acquire 1,000,000 events, and amongst these events, at least 100 leukemic cells should be there to call it as MRD positive sample. This gives a coefficient of variance (CV) as 10%. If the events acquired are less than this, the sensitivity gets reduced, and CV increases proportionately. However, it should be noted that the overall sensitivity of the MRD assay is not constant. It depends not only on the number of events acquired but also on the fact that to what extent the leukemic cells are separated from background population. For example, in B-ALL MRD analysis the sensitivity becomes high if the leukemic cells are easily distinguishable from normal B-cell precursors present in the background, as compared to a case where there is a significant overlap of marker profile between the normal precursors and the leukemic cells making it difficult to delineate the abnormal cells.

The other quality issue encountered during MRD testing is to deal with various type of artifacts. These include falsely altered antigenic intensities due to fluidics instability as well as a false increase in acquired events in disguise of air bubbles when the sample gets exhausted while the acquisition is still going on. To counteract these issues, it is advisable to monitor one parameter for each of the lasers over time [49]. The other artifact arises due to the simultaneous passing of two or more events across the laser (“doublets”). This artifact may significantly alter the true value of MRD. Special care to be taken during sample processing as well as acquisition to minimize this issue. Besides, during data analysis, doublet discrimination should be done with the help of plots for peak area, height and/or width [49].

Loss of cell viability is another issue which leads to altered scatter characteristics of the target population as well as the antigenic loss which can lead to spurious results. Application of viability gate (forward and side scatter gating) can significantly reduce this phenomenon [49]. The denominator used for enumerating residual leukemic cells also lacks standardization. A viability gate on forward scatter versus side scatter or all CD45 positive events or use of DNA-binding dye are commonly used methods for calculating the denominator [49]. DNA-binding dye seems to have an edge as in the past few years it has more takers due to its apparent closeness to all nucleated cell count on morphology.

MRD Calculation

The first step to calculate the MRD is to estimate the number of viable events from the flow cytometry plots which will serve as the denominator (described above in ‘quality control’ measures). Subsequently, the MRD events are quantified based on different LAIPs detected. The average number of events of LAIPs are calculated which becomes the numerator. Finally, MRD is given as percentage of average events of LAIPs to total viable events.

MRD Techniques Selection: MFC Versus PCR

The choice of MRD detection technique is dictated by several factors like the expertise of the laboratory, the resources available (manpower and finances) and the treatment regimen used/clinical trial design. The two most commonly used techniques viz. MFC and real-time quantitative (RQ)-PCR (for leukemia-associated clonal rearranged immunoglobulin and/or T-cell receptor (Ig/TCR) gene rearrangements and fusion transcripts), in some situations, are complementary to each other (Table 3). Results have shown a high level of concordance between the two techniques. However, the level of sensitivity by RQ-PCR is one log more than that by MFC [52, 53]. This reduced sensitivity has now been overtaken by the advanced version of MFC called as “next-generation flow cytometry [54, 55].”

Table 3.

Comparison of advantages and disadvantages of multiparameter flow cytometry and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction for MRD detection

| Technique of MRD | Multiparameter flow cytometry | Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (for immunoglobulin/T-cell receptor gene rearrangements or fusion transcripts) |

|---|---|---|

| Advantages | Rapid turn-around time | Detects MRD in all types of cases of B/T-ALL |

| Discrete cell population can be analysed | Higher sensitivity | |

| Given information about the viability of sample | Technique is well standardized with quality assurance | |

| Relatively less expensive | Targets for detection are stable over the period of disease | |

| Relatively less expertise required | ||

| Archival data can be easily stored | ||

| Disadvantages | False negative results in case of phenotypic shifts | Relatively expensive |

| False positive results due to similarity of immunophenotypes of regenerating B-cell precursors | Relatively higher turn-around time | |

| Limited standardization and quality assurance | Technically more complex | |

| May not be applicable in all cases of B/T-ALL (in cases of absence of lineage specific antigen) | Requires more expertise | |

| Amplification of DNA from dead cells | ||

| RNA instability in cases of MRD detection of fusion transcripts |

The advantages offered by conventional MFC are rapid turnaround time, allows analysis at a level of single cell/single population, gives information about the whole sample cellularity and viability, and the data produced can be easily stored. As compared to RQ-PCR, this technique is relatively less expensive. However, there are certain pitfalls and disadvantages of MFC which are overcome by RQ-PCR. One such scenario is that pertaining to the immunophenotypic shifts which render a particular antigen to be lost or gained during the treatment. For example, steroid therapy during the early induction phase of B-ALL often leads to modulation of antigens like down-regulation of CD10 and CD34 [56]. RQ-PCR overcomes this problem by targeting the regions which remain stable even after treatment and hence, easily quantifiable in follow-up samples. Another scenario is the absence of lineage-specific gating marker, e.g., CD19 in B-ALL, though seen in a very small proportion of cases [49]. In such scenarios, one has to be very cautious while analyzing and interpreting the MRD MFC data. RQ-PCR techniques are usually helpful in such cases.

The MFC techniques for MRD analysis is less well standardized, and there are no regular world-wide quality assurance (QA) programs [7]. This is due to the applicability of different treatment protocols and time points and hence, different antibody panels used by different centres. The RQ-PCR technique, on the other hand, is well standardized and have regular QA assessment schemes.

Future Considerations

During the last 5 years, new approaches for detection of MRD are coming up aiming at higher sensitivity and broader applicability. One such technique developed by EuroFlow Consortium is a high throughput “next-generation flow cytometry (NGF)” which employs ≥ eight colors and is based on analysis of data on multivariate plots where a test sample is compared with that of the standard one. The basic principles of this technique are principal component and canonical analysis [48, 54]. By this, a novel software (e.g., Infinicyt) measures the degree of deviation of maturation/differentiation in a test sample from the normal one. This technique has been fully standardized with regular QA assessments. Protocols defining the sample processing, instrument settings, antibodies to be used, data acquisition and analysis with appropriate gating strategies have been provided by the Consortium [57, 58]. This upcoming technique will likely to replace the current MFC protocols.

Another likely breakthrough for MRD quantification in near future will be next-generation sequencing (NGS). EuroClonality-NGS Consortium (https://www.euroclonalityngs.org/) has made guidelines/workflow as well as standardization for NGS-based Ig/TCR assays in hemato-oncology. This technique involves the characterization of leukemia-specific clonal Ig/TCR gene rearrangements in the diagnostic sample. The substantial benefit that it offers, is by utilizing the same set of primers as that for RQ-PCR. These sequences are then utilized for detection of MRD in the follow-up samples. This assay offers short turnaround time and better sensitivity (down to even 10−7) than Sanger sequencing-based assay. However, to achieve this high level of sensitivity, the amount of input DNA required should be large (~ 65 µg). This amount of DNA is often difficult to get in post-induction marrow samples. Another promising advantage of NGS-based assay can be detection of MRD from peripheral blood sample because of its higher sensitivity [59].

Conclusions

In the current era, MRD detection is no longer a research tool but now a routine standard of diagnostic care. MFC is still the most widely used technology for its detection which offers applicability in the majority of cases, have a fast throughput and is relatively less expensive. Much advances have been developed in MFC standardization with regards to MRD detection in ALL, but for AML it is still an ongoing process. Efforts are to be made towards harmonizing the operating protocols for the MFC MRD estimation among the different laboratories. This requires participation in various QA programs. But one has to recognize the fact that none of the MRD techniques are perfect and one has to do a proper selection as to when and where a particular technique is applicable.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:2391–2405. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown PA, Shah B, Fathi A, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: acute lymphoblastic leukemia, version 1.2017. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2017;15:1091–1102. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Donnell MR, Tallman MS, Abboud CN, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia, version 3.2017, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2017;15:926–957. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borowitz MJ, Devidas M, Hunger SP, et al. Clinical significance of minimal residual disease in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and its relationship to other prognostic factors: a Children’s Oncology Group study. Blood. 2008;111:5477–5485. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-132837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cavé H, van der Werff ten Bosch J, Suciu S, et al. Clinical significance of minimal residual disease in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:591–598. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808273390904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coustan-Smith E, Gajjar A, Hijiya N, et al. Clinical significance of minimal residual disease in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia after first relapse. Leukemia. 2004;18:499–504. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Dongen JJM, van der Velden VHJ, Brüggemann M, Orfao A. Minimal residual disease diagnostics in acute lymphoblastic leukemia: need for sensitive, fast, and standardized technologies. Blood. 2015;125:3996–4009. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-580027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neale G, Coustan-Smith E, Pan Q, et al. Tandem application of flow cytometry and polymerase chain reaction for comprehensive detection of minimal residual disease in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 1999;13:1221–1226. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conter V, Bartram CR, Valsecchi MG, et al. Molecular response to treatment redefines all prognostic factors in children and adolescents with B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results in 3184 patients of the AIEOP-BFM ALL 2000 study. Blood. 2010;115:3206–3214. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-248146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stow P, Key L, Chen X, et al. Clinical significance of low levels of minimal residual disease at the end of remission induction therapy in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115:4657–4663. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-253435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eckert C, Biondi A, Seeger K, et al. Prognostic value of minimal residual disease in relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet. 2001;358:1239–1241. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06355-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knechtli CJC, Goulden NJ, Hancock JP, et al. Minimal residula disease status as a predictor of relapse after allogenic bone marrow transplantation for children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 1998;102:860–871. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krejci O, van der Velden VHJ, Bader P, et al. Level of minimal residual disease prior to haematopoietic stem cell transplantation predicts prognosis in paediatric patients with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a report of the Pre-BMT MRD Study Group. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;32:849–851. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bader P, Kreyenberg H, Henze GHR, et al. Prognostic value of minimal residual disease quantification before allogeneic stem-cell transplantation in relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: the ALL-REZ BFM Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:377–384. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.6065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bader P, Kreyenberg H, von Stackelberg A, et al. Monitoring of minimal residual disease after allogeneic stem-cell transplantation in relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia allows for the identification of impending relapse: results of the ALL-BFM-SCT 2003 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1275–1284. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.4631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grupp SA, Kalos M, Barrett D, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for acute lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1509–1518. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Topp MS, Gökbuget N, Stein AS, et al. Safety and activity of blinatumomab for adult patients with relapsed or refractory B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:57–66. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Topp MS, Kufer P, Gökbuget N, et al. Targeted therapy with the T-cell-engaging antibody blinatumomab of chemotherapy-refractory minimal residual disease in B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients results in high response rate and prolonged leukemia-free survival. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2493–2498. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.7270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Appelbaum FR, Rosenblum D, Arceci RJ, et al. End points to establish the efficacy of new agents in the treatment of acute leukemia. Blood. 2007;109:1810–1816. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-041152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Dongen JJ, Seriu T, Panzer-Grümayer ER, et al. Prognostic value of minimal residual disease in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in childhood. Lancet. 1998;352:1731–1738. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)04058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruggemann M, Raff T, Flohr T, et al. Clinical significance of minimal residual disease quantification in adult patients with standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2005;107:1116–1123. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Percival M-E, Lai C, Estey E, Hourigan CS. Bone marrow evaluation for diagnosis and monitoring of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Rev. 2017;31:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al-Mawali A, Gillis D, Lewis I. The role of multiparameter flow cytometry for detection of minimal residual disease in acute myeloid leukemia. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;131:16–26. doi: 10.1309/AJCP5TSD3DZXFLCX. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campana D, Coustan-Smith E. Detection of minimal residual disease in acute leukemia by flow cytometry. Cytometry. 1999;38:139–152. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0320(19990815)38:4<139::AID-CYTO1>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Campana D (2003) Flow-cytometry—based studies of minimal residual disease in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, pp 21–36. 10.1007/978-1-59259-318-7_2

- 26.Behm FG, Raimondi SC, Schell MJ, et al. Lack of CD45 Antigen on blast cells in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia is associated with chromosomal hyperdiploidy and other favorable prognostic features. Blood. 1992;79:1011–1016. doi: 10.1182/blood.V79.4.1011.bloodjournal7941011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DiGiuseppe JA, Fuller SG, Borowitz MJ. Overexpression of CD49f in precursor B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: potential usefulness in minimal residual disease detection. Cytom Part B Clin Cytom. 2009;76B:150–155. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.20440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamazani FM, Bahoush GR, Aghaeipour M, et al. CD44 and CD27 expression pattern in B cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia and its clinical significance. Med Oncol. 2013;30:359. doi: 10.1007/s12032-012-0359-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cox CV, Diamanti P, Blair A. Investigating the expression of the MRD Marker CD58 on leukaemia initiating cells in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Blood. 2011;118:1887. doi: 10.1182/blood.V118.21.1887.1887. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeidan MA, Kamal HM, Shabrawy EL, Shabrawy DA, et al. Significance of CD34/CD123 expression in detection of minimal residual disease in B-ACUTE lymphoblastic leukemia in children. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2016;59:113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tembhare PR, Ghogale S, Ghatwai N, et al. Evaluation of new markers for minimal residual disease monitoring in B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia: CD73 and CD86 are the most relevant new markers to increase the efficacy of MRD 2016; 00B: 000-000. Cytom Part B Clin Cytom. 2018;94:100–111. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.21486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sędek Ł, Theunissen P, Sobral da Costa E, et al. Differential expression of CD73, CD86 and CD304 in normal vs. leukemic B-cell precursors and their utility as stable minimal residual disease markers in childhood B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Immunol Methods. 2018;5:4. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2018.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsitsikov E, Harris MH, Silverman LB, et al. Role of CD81 and CD58 in minimal residual disease detection in pediatric B lymphoblastic leukemia. Int J Lab Hematol. 2018;40:343–351. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.12795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cherian S, Miller V, McCullouch V, et al. A novel flow cytometric assay for detection of residual disease in patients with B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma post anti-CD19 therapy. Cytom Part B Clin Cytom. 2018;94:112–120. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.21482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rhein P, Mitlohner R, Basso G, et al. CD11b is a therapy resistance- and minimal residual disease-specific marker in precursor B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115:3763–3771. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-247585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Porwit-MacDonald A, Björklund E, Lucio P, et al. BIOMED-1 Concerted Action report: flow cytometric characterization of CD7+ cell subsets in normal bone marrow as a basis for the diagnosis and follow-up of T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) Leukemia. 2000;14:816–825. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roshal M, Fromm JR, Winter S, et al. Immaturity associated antigens are lost during induction for T cell lymphoblastic leukemia: implications for minimal residual disease detection. Cytom Part B Clin Cytom. 2010;78B:139–146. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.20511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Macedo A, Orfão A, Vidriales MB, et al. Characterization of aberrant phenotypes in acute myeloblastic leukemia. Ann Hematol. 1995;70:189–194. doi: 10.1007/BF01700374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Mawali A, Gillis D, Hissaria P, Lewis I. Incidence, sensitivity, and specificity of leukemia-associated phenotypes in acute myeloid leukemia using specific five-color multiparameter flow cytometry. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:934–945. doi: 10.1309/FY0UMAMM91VPMR2W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu J, Jorgensen JL, Wang SA. How do we use multicolor flow cytometry to detect minimal residual disease in acute myeloid leukemia? Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:787–802. doi: 10.1016/J.CLL.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cruz NM, Mencia-Trinchant N, Hassane DC, Guzman ML. Minimal residual disease in acute myelogenous leukemia. Int J Lab Hematol. 2017;39:53–60. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.12670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zeijlemaker W, Kelder A, Oussoren-Brockhoff YJM, et al. A simple one-tube assay for immunophenotypical quantification of leukemic stem cells in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2016;30:439–446. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coustan-Smith E, Sancho J, Hancock ML, et al. Use of peripheral blood instead of bone marrow to monitor residual disease in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2002;100:2399–2402. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brisco MJ, Sykes PJ, Hughes E, et al. Monitoring minimal residual disease in peripheral blood in B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 1997;99:314–319. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.3723186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van der Velden VHJ, Jacobs DCH, Wijkhuijs AJM, et al. Minimal residual disease levels in bone marrow and peripheral blood are comparable in children with T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), but not in precursor-B-ALL. Leukemia. 2002;16:1432–1436. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Velden VHJ, Hoogeveen PG, Pieters R, Dongen JJM. Impact of two independent bone marrow samples on minimal residual disease monitoring in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2006;133:382–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gaipa G, Basso G, Biondi A, Campana D. Detection of minimal residual disease in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cytom Part B Clin Cytom. 2013;84:359–369. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.21101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Preffer F, Dombkowski D. Advances in complex multiparameter flow cytometry technology: applications in stem cell research. Cytom Part B Clin Cytom. 2009;76B:295–314. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.20480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wood BL. Flow cytometric monitoring of residual disease in acute leukemia. Totowa: Humana Press; 2013. pp. 123–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Theunissen P, Mejstrikova E, Sedek L, et al. Standardized flow cytometry for highly sensitive MRD measurements in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2017;129:347–357. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-07-726307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patkar N, Alex AA, Bargavi B, et al. Standardizing minimal residual disease by flow cytometry for precursor B lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a developing country. Cytom Part B Clin Cytom. 2012;82B:252–258. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.21017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Malec M, van der Velden VHJ, Björklund E, et al. Analysis of minimal residual disease in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: comparison between RQ-PCR analysis of Ig/TcR gene rearrangements and multicolor flow cytometric immunophenotyping. Leukemia. 2004;18:1630–1636. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Neale GAM, Coustan-Smith E, Stow P, et al. Comparative analysis of flow cytometry and polymerase chain reaction for the detection of minimal residual disease in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2004;18:934–938. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Costa ES, Pedreira CE, Barrena S, et al. Automated pattern-guided principal component analysis vs expert-based immunophenotypic classification of B-cell chronic lymphoproliferative disorders: a step forward in the standardization of clinical immunophenotyping. Leukemia. 2010;24:1927–1933. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pedreira CE, Costa ES, Lecrevisse Q, et al. Overview of clinical flow cytometry data analysis: recent advances and future challenges. Trends Biotechnol. 2013;31:415–425. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gaipa G, Basso G, Maglia O, et al. Drug-induced immunophenotypic modulation in childhood ALL: implications for minimal residual disease detection. Leukemia. 2005;19:49–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van Dongen JJM, Lhermitte L, Böttcher S, et al. EuroFlow antibody panels for standardized n-dimensional flow cytometric immunophenotyping of normal, reactive and malignant leukocytes. Leukemia. 2012;26:1908–1975. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kalina T, Flores-Montero J, van der Velden VHJ, et al. EuroFlow standardization of flow cytometer instrument settings and immunophenotyping protocols. Leukemia. 2012;26:1986–2010. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reyes-Barron C, Burack WR, Rothberg PG, Ding Y. Next-generation sequencing for minimal residual disease surveillance in acute lymphoblastic leukemia: an update. Crit Rev Oncog. 2017;22:559–567. doi: 10.1615/CritRevOncog.2017020588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]