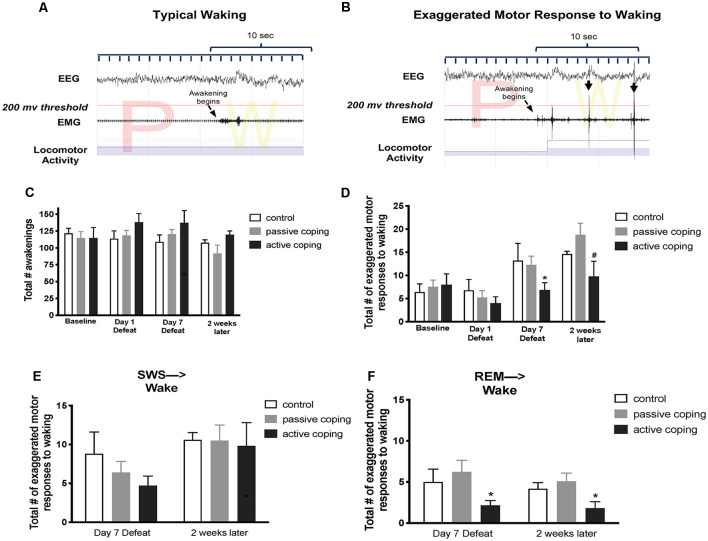

Figure 4.

Number of exaggerated motor responses during transitions to waking from SWS or REM sleep in the light period at baseline, Day 1 of defeat, Day 7 of defeat, and 2 weeks after the last defeat. (A) Representative typical awakening: a trace of EEG, EMG, and locomotor activity data during arousal from a REM sleep episode (initiated at arrow). Note that EMG spikes do not go above the 200 μV threshold in red within 10 s of the sleep transition. (B) Representative exaggerated motor response at awakening: a trace of EEG, EMG, and locomotor activity data during arousal from a REM sleep episode (initiated at arrow). Note the recurrent EMG spikes greater than 200 μV (denoted with black arrows) that occur within 10 s of the sleep transition with concurrent locomotor activity. (C) Total counts of awakenings during 6 h of the light period at baseline, defeat day 1, defeat day 7, and 2 weeks after the last defeat exposure. No significant differences in the total number of awakenings were detected between groups at any time point. (D) Total counts of exaggerated motor responses to waking during 6 h of the light period at baseline, defeat day 1, defeat day 7, and 2 weeks after the last defeat exposure. Actively coping rats (n = 8) displayed less exaggerated motor responses to waking than both control (n = 7) and passively coping rats (n = 15) after day 7 of defeat, and this persisted 2 weeks later. (E,F) Exaggerated motor responses counted separately for arousals from SWS and REM sleep, respectively. Compared to control (n = 7) and passively coping rats (n = 15), actively coping rats (n = 8) had significantly fewer exaggerated motor responses to waking from REM sleep specifically but not from SWS. *P < 0.05, #P < 0.1.