Abstract

Background

Although surgical site infection (SSI) is one of the most studied healthcare-associated infections, the global burden of SSI after appendectomy remains unknown.

Objective

We estimated the incidence of SSI after appendectomy at global and regional levels.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Participants

Appendectomy patients.

Data sources

EMBASE, PubMed and Web of Science were searched, with no language restrictions, to identify observational studies and clinical trials published between 1 January 2000 and 30 December 2018 and reporting on the incidence of SSI after appendectomy. A random-effect model meta-analysis served to obtain the pooled incidence of SSI after appendectomy.

Results

In total, 226 studies (729 434 participants from 49 countries) were included in the meta-analysis. With regard to methodological quality, 59 (26.1%) studies had low risk of bias, 147 (65.0%) had moderate risk of bias and 20 (8.8%) had high risk of bias. We found an overall incidence of SSI of 7.0 per 100 appendectomies (95% prediction interval: 1.0–17.6), varying from 0 to 37.4 per 100 appendectomies. A subgroup analysis to identify sources of heterogeneity showed that the incidence varied from 5.8 in Europe to 12.6 per 100 appendectomies in Africa (p<0.0001). The incidence of SSI after appendectomy increased when the level of income decreased, from 6.2 in high-income countries to 11.1 per 100 appendectomies in low-income countries (p=0.015). Open appendectomy (11.0 per 100 surgical procedures) was found to have a higher incidence of SSI compared with laparoscopy (4.6 per 100 appendectomies) (p=0.0002).

Conclusion

This study suggests a high burden of SSI after appendectomy in some regions (especially Africa) and in low-income countries. Strategies are needed to implement and disseminate the WHO guidelines to decrease the burden of SSI after appendectomy in these regions.

Prospero registration number

CRD42017075257.

Keywords: epidemiology, health policy, quality in health care, Public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This meta-analysis is the first to summarise the global incidence of surgical site infections after appendectomy.

We investigated WHO region, level of income and surgical procedure as sources of heterogeneity.

We were not able to investigate all sources of heterogeneity due to missing information in the original studies.

There were few studies from low-income countries and from Africa.

Introduction

Defined as an acute inflammation of the vermiform appendix,1 evidence abounds that acute appendicitis is the most common abdominal surgical emergency,2 with an incidence of almost 100 per 100 000 person-years reported in Australia, Europe and North America.3 4 Evidence suggests appendectomy, the surgical removal of the vermiform appendix, as first-line treatment for acute appendicitis, although antibiotic therapy may be efficacious for a selected group of patients with uncomplicated acute appendicitis.5–7 Appendectomy is a relatively safe surgical intervention with a case fatality rate of 2.1–2.4 per 1000 patients, as reported in studies conducted in Europe.8 9

Innovations in appendectomy, especially with the advent of minimally invasive or laparoscopic surgery in 1983,10 which has replaced the traditional open appendectomy in most of high-income countries, have led to a drastic reduction in the morbidity and mortality related to appendectomy.11–13 Laparoscopic appendectomy is now recognised as the gold standard surgical approach for uncomplicated acute appendicitis owing to its merits over open surgery: less postoperative pain, reduced postoperative ileus, shorter hospital stay, rapid postoperative recovery and better aesthetic scars.14–19

However, regardless of the surgical technique (laparoscopic or open surgery), appendectomy remains a sceptic surgical intervention associated with a substantial risk of surgical site infections (SSIs). SSIs after appendectomy are postoperative nosocomial infections affecting the incision site, deep tissues and organs at the operative site within 30 days after the surgical procedure.20–22 SSI following appendectomy is a serious postoperative medical concern that increases the financial burden for both the healthcare system and the patient. It also has a negative impact on the patient’s health-related quality of life.23–28

SSI is both the most frequently studied and the leading healthcare-associated infection reported hospital-wide in low-income and middle-income countries.29 A recently published prospective, international, multicentre cohort study suggested a higher burden of SSIs after any gastrointestinal surgery in low-income countries compared with high-income countries.30 However, there is no global systematic review with meta-analysis reporting the burden of SSI after appendectomy or comparing the burden between regions and between country level of income. It would be interesting to have such accurately estimated data to construct efficient strategies to globally curb the burden of SSI after appendectomy. To fill this gap, the current systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to summarise contemporary data on the occurrence of SSI after appendectomy.

Methods

Design

This systematic review and meta-analysis was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO). The protocol has been published in a peer-reviewed journal.31 This review is reported according to the guidelines of the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.32 33

Eligibility criteria

We considered observational studies (cross-sectional, case–control and cohort) and clinical trials of appendectomy patients. The outcome of interest was incidence of SSI in patients with appendectomy (or enough data to compute this estimate, i.e. number of cases of SSI and sample size). We excluded letters, reviews, commentaries and editorials, and studies that lacked key data and/or explicit method description, as well as studies where relevant data on SSI after appendectomy were impossible to extract even after contacting the corresponding author.

Search strategy

We searched EMBASE, PubMed and Web of Science (Web of Science Core Collection, Current Contents Connect, KCI-Korean Journal Database, SciELO Citation Index, Russian Science Citation Index) to identify observational studies published between 1 January 2000 and 30 December 2018. No language restrictions were applied. The initial search strategy was designed for EMBASE and was adapted for use in other databases. The search strategy, as illustrated in online supplementary table 1 and in the study protocol,31 was based on a combination of relevant text words and medical subject headings related to SSI. Moreover, the references of all relevant articles found were scrutinised for potential additional data sources. When a full text was not available, it was requested via the corresponding author by email. For duplicates or studies published in more than one report, the one reporting the largest sample size was considered.

bmjopen-2019-034266supp001.pdf (2MB, pdf)

Study selection

Two reviewers (CD and AM) independently screened the title and abstract of articles for eligibility. Full texts of potentially eligible articles were retrieved and screened for final inclusion. Disagreements between the two reviewers were solved by discussion, and when a consensus was not reached a third reviewer (JNT) resolved discrepancies. Studies in languages other than French, English and Spanish were translated using Google Translate.

Data extraction and management

A standardised and pretested data extraction form was used by five reviewers (CD, JNT, AM, RNTN, CMM) to independently extract data from individual studies. A sixth reviewer (JJB) independently extracted the data for accuracy. The last name of the first author, year of publication, country, study design, age groups, sample size, mean or median age, proportion of men, specific conditions of the study population, the surgical method (open surgery or laparoscopy), and incidence of SSI after appendectomy in the study population (or enough data to compute this estimate) were extracted.

To assess the methodological quality of each study, two reviewers (CD and CMM) used an adapted version of the bias assessment tool for prevalence studies developed by Hoy and colleagues.34

Data synthesis and analysis

A meta-analysis was used to summarise data on the incidence of SSIs by pooling together data of studies reporting the incidence of SSIs. Study-specific estimates were then pooled through a DerSimonian and Laird random-effects meta-analysis model to obtain an overall summary estimate of the incidence across studies, after stabilising the variance of individual studies using the Freeman-Tukey double arc-sine transformation.35 Incidence was expressed by 100 surgical procedures for appendectomy with their 95% CI and 95% prediction interval. Heterogeneity was evaluated using the χ² test on Q statistic, which is quantified by I² values,36 assuming that I² values of 25%, 50% and 75% represent low, medium and high heterogeneity, respectively.37 Where substantial heterogeneity (I² >50%) was detected, a subgroup analysis was performed to detect possible sources using the following grouping variables: type of surgery (laparoscopy or open), WHO region and country level of income. A p value <0.05 was indicative of statistically significant difference. A meta-regression analysis was performed to estimate the explained heterogeneity of each covariate included in the subgroup analysis. Inter-rater agreement for study inclusion was assessed using Cohen’s κ coefficient.38 Funnel plot analysis and Egger’s test (p<0.10) were performed to detect the presence of publication bias.39 Since we assumed that the incidence estimates of interest would likely be published even if substantially different from previously reported estimates, we have not reported adjusted incidence estimate in the case of publication bias. Data were analysed using the ‘meta’ package in R V.3.6.1.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination of our research.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

Overall, 619 records were initially identified. After removal of duplicates, and screening of study titles, abstracts and full texts, 226 studies including 729 434 patients remained for meta-analysis (online supplementary figure 1). The full list of included studies is in the online supplementary appendix 1. With regard to methodological quality, 59 (26.1%) studies had low risk of bias, 147 (65.0%) moderate risk of bias and 20 (8.8%) high risk of bias. The characteristics of the included studies are presented in online supplementary table 2. Among the included studies, 154 were conducted in high-income, 36 in upper-middle, 27 in lower-middle and 9 in low-income countries. Overall, most of the studies were from Europe (n=68) and the Americas (n=67). SSI was defined according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria in 50 studies, while 25 studies used other criteria. The definition of SSI was not clearly given in 151 studies. Individual characteristics of the included studies are shown in online supplementary table 3.

Overall incidence

The overall incidence of SSI after appendectomy was 7.0 per 100 appendectomies (95% prediction interval: 1.0–17.6), varying from 0% to 37.4%, with substantial heterogeneity and publication bias (online supplementary figure 2). The sensitivity analysis including only studies with low risk of bias yielded a very close incidence to crude analysis (table 1).

Table 1.

Summary statistics of meta-analysis of the incidence of surgery site infections after appendectomy

| Incidence per 100 surgical procedures (95% CI) | 95% prediction interval | Studies (n) | Participants (n) | H (95% CI) | I² (95% CI) | P heterogeneity | P Egger’s test | P difference | |

| Global | 7.0 (6.4 to 7.7) | 1.0–17.7 | 226 | 729 434 | 8.9 (8.7 to 9.1) | 98.7 (98.7 to 98.8) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | – |

| Low risk of bias | 6.9 (6.0 to 7.9) | 1.6–15.2 | 59 | 204 450 | 6.7 (6.3 to 7.1) | 97.7 (97.4 to 98.0) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | – |

| By level of income | |||||||||

| Low | 11.1 (5.5 to 18.2) | 0.0–42.2 | 9 | 1496 | 3.8 (3.0 to 4.8) | 93.1 (89.0 to 95.6) | <0.0001 | 0.735 | 0.015 |

| Lower-middle | 9.2 (6.3 to 12.6) | 0.0–31.6 | 27 | 10 379 | 5.1 (4.6 to 5.7) | 96.2 (95.3 to 96.9) | <0.0001 | 0.960 | |

| Upper-middle | 8.5 (6.5 to 10.8) | 0.3–25.3 | 36 | 26 557 | 5.4 (2.9 to 5.9) | 96.6 (95.9 to 97.1) | <0.0001 | 0.392 | |

| High | 6.2 (5.6 to 6.9) | 0.9–15.3 | 154 | 691 002 | 9.5 (9.2 to 9.8) | 98.9 (98.8 to 99.0) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| By WHO regions | |||||||||

| Africa | 12.6 (3.3 to 26.4) | 0.0–72.5 | 8 | 3001 | 9.1 (7.9 to 10.5) | 98.8 (98.4 to 99.1) | <0.0001 | 0.628 | <0.0001 |

| Western Pacific | 9.6 (8.1 to 11.2) | 2.3–20.8 | 43 | 30 822 | 3.8 (3.5 to 4.2) | 93.2 (91.7 to 94.4) | <0.0001 | 0.150 | |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 8.2 (6.4 to 10.2) | 1.7–18.6 | 23 | 7779 | 2.6 (2.2 to 3.1) | 85.3 (79.1 to 89.6) | <0.0001 | 0.515 | |

| South-East Asia | 7.6 (4.7 to 11.1) | 0.0–24.6 | 16 | 5782 | 3.8 (3.2 to 4.5) | 93.0 (90.1 to 95.0) | <0.0001 | 0.0001 | |

| The Americas | 5.9 (5.2 to 6.6) | 1.9–11.7 | 67 | 401 931 | 7.5 (7.1 to 7.9) | 98.2 (98.0 to 98.4) | <0.0001 | 0.0004 | |

| Europe | 5.8 (4.6 to 7.0) | 0.0–19.1 | 68 | 276 793 | 10.4 (10.0 to 10.8) | 99.1 (99.0 to 99.1) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| By type of surgical procedure | |||||||||

| Laparoscopy with open surgery | 4.6 (2.5 to 7.2) | 0.0–15.6 | 10 | 4892 | 3.2 (2.6 to 4.2) | 90.7 (85.0 to 94.2) | <0.0001 | 0.942 | 0.0002 |

| Laparoscopy | 4.6 (3.4 to 5.9) | 0.0–14.3 | 40 | 33 873 | 4.4 (4.0 to 4.8) | 94.7 (93.6 to 95.7) | <0.0001 | 0.0002 | |

| Open surgery | 11.0 (7.9 to 14.4) | 0.0–39.3 | 44 | 13 120 | 5.7 (5.2 to 6.1) | 96.9 (96.4 to 97.3) | <0.0001 | 0.077 |

H, H statistics.

Sources of heterogeneity

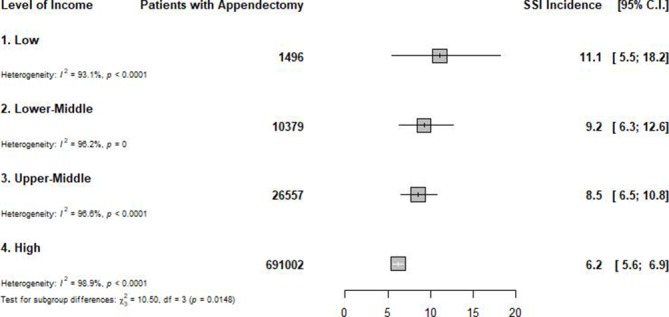

According to country level of income (figure 1 and online supplementary appendix 1), the incidence of SSI after appendectomy increased when the level of income decreased, from 6.2 in high-income countries to 11.1 per 100 appendectomies in low-income countries (p=0.015) (table 1).

Figure 1.

Global incidence of surgical site infection after appendectomy, by level of country income.SSI: surgical-site infection; C.I.: confidence intervals.

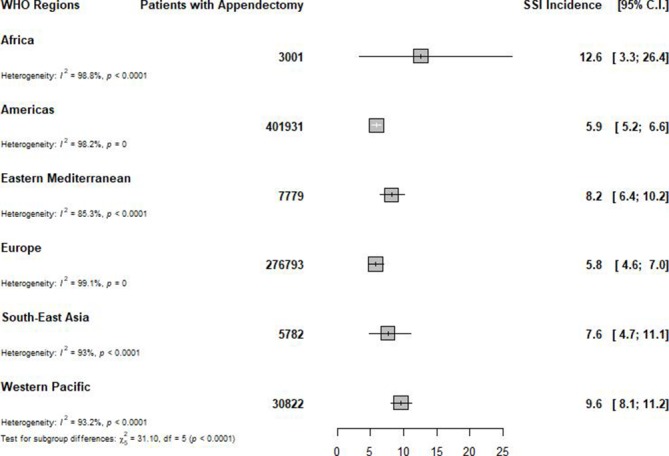

The incidence varied widely across the WHO regions (figure 2 and online supplementary appendix 1), from 5.8 in Europe to 12.6 per 100 surgical procedures in Africa (p<0.0001) (table 1). Two regions (Europe and the Americas) had an incidence of <6 per 100 appendectomies, three an incidence between 6 and 10 per 100 appendectomies (South-East Asia, Eastern Mediterranean and Western Pacific), and one an incidence of >10 per 100 appendectomies (Africa) (table 1). The incidence also varied widely within different regions. The incidence varied from 0.2 to 32.0 in Africa, 1.9 to 37.4 in Western Pacific, 1.3 to 33.8 in Eastern Mediterranean, 1.2 to 25.8 in South-East Asia, 0.1 to 37.4 in the Americas, and 0 to 20.0 per 100 appendectomies in Europe (figure 2 and online supplementary appendix 1).

Figure 2.

Global incidence of surgical site infection after appendectomy, by WHO region.SSI: surgical-site infection; C.I.: confidence intervals.

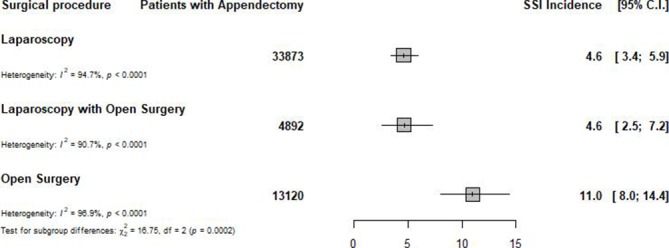

Open appendectomy, with an incidence of 11.0 (95% prediction interval: 0.0–39.3) per 100 appendectomies, was found to have a higher incidence of SSI compared with laparoscopic appendectomy, which has an incidence of 4.6 (95% prediction interval: 0.0–14.3) per appendectomies (p=0.0002) (figure 3 and online supplementary appendix 1).

Figure 3.

Global incidence of surgical site infection after appendectomy, by type of surgical procedure.SSI: surgical-site infection; C.I.: confidence intervals.

Heterogeneity in the overall incidence of SSI after appendectomy was explained by WHO region (17.1%), country level of income (11.1%) and type of surgical procedure (4.9%). We conducted a post-hoc analysis; then in a meta-regression analysis of 119 studies reporting data on the use of antibiotics, there was no association between variation in SSI incidence and proportion of patients with antibiotics (coefficient: 0.0010 (95% CI −0.0004 to 0.0023), p=0.170). However, most (79.5%) of these studies reported use of antibiotics in all patients.

Discussion

This first systematic review and meta-analysis of data on 729 434 appendectomies in 226 studies from 49 countries found an overall incidence of SSI of 7.0 per 100 surgical procedures for appendectomy, varying from 0 to 37.4 per 100 appendectomies, with substantial heterogeneity according to WHO region, country level of income and type of surgical procedure. The incidence increased with decreasing country level of income and was higher when using open surgery compared with laparoscopy. The incidence significantly varied by WHO region, with Africa having the highest burden, followed by the Western Pacific, Eastern Mediterranean and South-East Asia. We found no association between SSI incidence and proportion of patients using antibiotics.

Healthcare-associated infections are acquired by patients when receiving care and are the most frequent adverse event affecting patient safety worldwide. These include SSI after appendectomy.40 As reported in a previous systematic review and meta-analysis, SSI was the leading infection in hospitals in developed countries.29 The high incidence we found in this study suggests that SSI after appendectomy remains a global public health concern. WHO reported that in every 100 hospitalised patients at any given time, 7 in developed and 15 in developing countries will acquire at least one healthcare-associated infection.40 SSIs are mainly caused by micro-organisms resistant to commonly used antimicrobials, which can be multidrug-resistant. Indeed, more than 50% of SSIs can be antibiotic-resistant.41 The leading micro-organisms identified in SSIs are Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative staphylococci and Escherichia coli, as reported by the National Healthcare Safety Network.41 It is a concern since S. aureus and E. coli are the micro-organisms with the highest proportion of antibiotic resistance, respectively resistant to oxacillin/methicillin in 43% of cases and to fluoroquinolones in 25% of cases.41 A recent international prospective cohort study has shown that 21.6% of patients with SSI after any gastrointestinal surgery had an infection that was resistant to the prophylactic antibiotics used.30 There are many factors that can favour SSI, including patient-related and procedural-related factors.42 These factors can be classified into two categories: non-modifiable factors such as age and sex, and modifiable factors including nutritional status, tobacco use, correct use of antibiotics, obesity, diabetes, prolonged duration of surgery, presurgery hospital stay of at least 2 days, lower volume of hospital and surgeons, and intraoperative techniques.40 Strategies to curb the burden of SSIs should therefore focus on addressing these identified factors. However, we were not able to find an association between SSI and use antibiotics, which may be due to the low variability in the proportion of antibiotics in the original studies.

In the current study looking specifically at SSI after appendectomy, we also found that SSI was higher in low-income countries. Interestingly, there was a trend of increasing incidence when the country level of income decreased. In this study, the WHO Africa region, essentially composed of sub-Saharan Africa, was the region with the highest incidence. The WHO estimates that the endemic burden of healthcare-associated infections is two to three times significantly higher in low-income and middle-income countries than in high-income nations.40 The highest burden found in Africa may be associated with the fact that most of the countries in this continent are low-income countries with perhaps limited resources for perioperative spesis control compared with other regions. Indeed, factors associated with increased risk of SSI after appendectomy may be higher in low-income settings. The burden of diabetes, obesity and undernutrition is increasing in low-income countries.43 44 There is also inadequate use of antimicrobials in low-income and middle-income countries, and micro-organisms are more resistant to prophylactic antibiotics used to prevent SSI in low-income countries compared with high-income countries.30 45 46 Lower level income is also associated with lower volume of surgeons and hospitals, factors that are recognised to be associated with increased risk for SSIs.40 The higher incidence found in low-income countries may also be explained by the fact that open surgery is the most used surgical procedure in this setting. Indeed, we found, as in other studies, that open surgery is associated with higher incidence of SSI compared with laparoscopy.47 48 Laparoscopy is generally indicated for uncomplicated appendicitis, where the spread of micro-organism is lower compared with open surgery indicated for perforated appendicitis, with peritonitis for example. Moreover, compared with high-income countries, only few low-income countries have the necessary infrastructure to carry out laparoscopy procedures.49–51

Our findings have important implications for healthcare providers and health policy makers. SSIs are among the most preventable healthcare-associated infections.52 53 They still represent a significant burden in terms of patient morbidity and mortality and additional costs for healthcare systems.40 The prevention of SSI has received considerable attention from surgeons, infection control professionals, health policy makers, the media and the public since there is a perception among the public that SSIs may reflect poor quality of care.54 However, special attention is needed in low-income countries and Africa. Strategy to curb the burden of SSIs after appendectomy, as for other surgery procedures, should be focused on strategies that can help address factors associated with increased risk of SSIs. Therefore, such strategies should be a package that includes how to address the factors cited above. The 26 WHO recommendations on preventing SSIs should be disseminated and implemented,40 especially in low-income countries. Strengthening the healthcare systems of low-income countries and of the countries in the WHO Afro region is of paramount importance, and can be achieved by educating and providing training to healthcare providers to enhance their skills in performing less invasive surgical procedures.

This study should however be interpreted in the context of some drawbacks. First, the included studies used different definitions of SSIs. In addition, there was some heterogeneity in terms of the surgical procedure and the profile of patients. This may have led to an overestimation or underestimation of SSI incidence by individual studies (depending on the study characteristics). Second, few studies reported on participants’ characteristics and details of the surgical procedure, which can modify the risk of developing SSIs. We were not therefore able to measure their impact on our outcome of interest. Third, only a quarter of studies had low risk of bias; however, our analysis including only studies with low risk of bias yielded an estimate close to the crude incidence. Fourth, the various geographical regions and countries were variably represented, with some countries having only one study or even no study, and this could affect the generalisability of our findings.

Despite these limitations, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to provide a global estimate of the burden of SSI after appendectomy. A protocol had been published, and we used rigorous methodological and statistical procedures to obtain and pool data. Furthermore, subgroup analyses were conducted to investigate the various factors likely to affect our estimate.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis compiled data from more than 700 000 people with appendicitis in 49 countries and pointed a high incidence of SSI after appendectomy, at 7 per 100 appendectomies. This estimate seemed higher in some WHO regions (especially Africa) and in low-income countries. These data suggest that less invasive procedure is associated with low incidence of SSI after appendectomy. Strategies are needed to implement already known guidelines to decrease the burden of SSI after appendectomy. However, in low-income countries which have weak health systems, cost-effectiveness studies are needed to inform policies on the best strategies to decrease the burden of SSI after appendectomy.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: CD and JJB conceived the idea of the study and developed the protocol. JJB, CD and JNT did the literature search. CD, AM and JNT selected the studies. CD, JNT, RNTN, AM, CMM and JJB extracted the relevant information. CD, JJB and CMM synthesised the data. CD, JNT, CMM and JJB wrote the first draft of the paper. CD, JJB, JNT, AB, RNTN, CMM, MLG and AE critically revised the successive drafts of the paper and approved the final version. MLG and AE supervised the overall work. CD and JJB are the guarantors of the review.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1. Giesen LJX, van den Boom AL, van Rossem CC, et al. . Retrospective multicenter study on risk factors for surgical site infections after appendectomy for acute appendicitis. Dig Surg 2017;34:103–7. 10.1159/000447647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Navarro Fernández JA, Tárraga López PJ, Rodríguez Montes JA, et al. . Validity of tests performed to diagnose acute abdominal pain in patients admitted at an emergency department. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2009;101:610–8. 10.4321/S1130-01082009000900003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ohmann C, Franke C, Kraemer M, et al. . [Status report on epidemiology of acute appendicitis]. Chirurg 2002;73:769–76. 10.1007/s00104-002-0512-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Körner H, Söreide JA, Pedersen EJ, et al. . Stability in incidence of acute appendicitis. A population-based longitudinal study. Dig Surg 2001;18:61–6. 10.1159/000050099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Martínez Carrilero J. [Safety an efficacy of antibiotics compared with appendicectomy for treatment of uncomplicated acute appendicitis: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials]. Rev Clin Esp 2012;212:460–60. 10.1016/j.rce.2012.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Varadhan KK, Neal KR, Lobo DN. Safety and efficacy of antibiotics compared with appendicectomy for treatment of uncomplicated acute appendicitis: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2012;344:e2156–e56. 10.1136/bmj.e2156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Masoomi H, Nguyen NT, Dolich MO, et al. . Laparoscopic appendectomy trends and outcomes in the United States: data from the nationwide inpatient sample (NIS), 2004-2011. Am Surg 2014;80:1074–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kotaluoto S, Ukkonen M, Pauniaho S-L, et al. . Mortality related to appendectomy; a population based analysis over two decades in Finland. World J Surg 2017;41:64–9. 10.1007/s00268-016-3688-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Blomqvist PG, Andersson REB, Granath F, et al. . Mortality after appendectomy in Sweden, 1987–1996. Ann Surg 2001;233:455–60. 10.1097/00000658-200104000-00001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Semm K. Endoscopic appendectomy. Endoscopy 1983;15:59–64. 10.1055/s-2007-1021466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Xiao Y, Shi G, Zhang J, et al. . Surgical site infection after laparoscopic and open appendectomy: a multicenter large consecutive cohort study. Surg Endosc 2015;29:1384–93. 10.1007/s00464-014-3809-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Varela JE, Wilson SE, Nguyen NT. Laparoscopic surgery significantly reduces surgical-site infections compared with open surgery. Surg Endosc 2010;24:270–6. 10.1007/s00464-009-0569-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bregendahl S, Nørgaard M, Laurberg S, et al. . Risk of complications and 30-day mortality after laparoscopic and open appendectomy in a Danish region, 1998-2007; a population-based study of 18,426 patients. Pol Przegl Chir 2013;85:395–400. 10.2478/pjs-2013-0060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sauerland S, Jaschinski T, Neugebauer EAM, et al. . Laparoscopic versus open surgery for suspected appendicitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010;23:CD001546–CD46. 10.1002/14651858.CD001546.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aziz O, Athanasiou T, Tekkis PP, et al. . Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy in children. Ann Surg 2006;243:17–27. 10.1097/01.sla.0000193602.74417.14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dai L, Shuai J. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy in adults and children: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. United European Gastroenterol J 2017;5:542–53. 10.1177/2050640616661931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Markides G, Subar D, Riyad K. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy in adults with complicated appendicitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg 2010;34:2026–40. 10.1007/s00268-010-0669-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wei B, Qi C-L, Chen T-F, et al. . Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy for acute appendicitis: a metaanalysis. Surg Endosc 2011;25:1199–208. 10.1007/s00464-010-1344-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li X, Zhang J, Sang L, et al. . Laparoscopic versus conventional appendectomy - a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Gastroenterol 2010;10:129–29. 10.1186/1471-230X-10-129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Martone WJ, et al. . CDC definitions of nosocomial surgical site infections, 1992: a modification of CDC definitions of surgical wound infections. Am J Infect Control 1992;20:271–4. 10.1016/S0196-6553(05)80201-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Culver DH, Horan TC, Gaynes RP, et al. . Surgical wound infection rates by wound class, operative procedure, and patient risk index. National nosocomial infections surveillance system. Am J Med 1991;91:152S–7. 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90361-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care–associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control 2008;36:309–32. 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Badia JM, Casey AL, Petrosillo N, et al. . Impact of surgical site infection on healthcare costs and patient outcomes: a systematic review in six European countries. J Hosp Infect 2017;96:1–15. 10.1016/j.jhin.2017.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thompson KM, Oldenburg WA, Deschamps C, et al. . Chasing zero: the drive to eliminate surgical site infections. Ann Surg 2011;254:430–7. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31822cc0ad [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hawn MT, Vick CC, Richman J, et al. . Surgical site infection prevention: time to move beyond the surgical care improvement program. Ann Surg 2011;254:494–501. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31822c6929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mehta JA, Sable SA, Nagral S. Updated recommendations for control of surgical site infections. Ann Surg 2015;261:e65 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318289c5fd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Andersson RE. Short-Term complications and long-term morbidity of laparoscopic and open appendicectomy in a national cohort. Br J Surg 2014;101:1135–42. 10.1002/bjs.9552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pinkney TD, Calvert M, Bartlett DC, et al. . Impact of wound edge protection devices on surgical site infection after laparotomy: multicentre randomised controlled trial (ROSSINI trial). BMJ 2013;347:f4305–f05. 10.1136/bmj.f4305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Allegranzi B, Bagheri Nejad S, Combescure C, et al. . Burden of endemic health-care-associated infection in developing countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2011;377:228–41. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61458-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. GlobalSurg Collaborative Surgical site infection after gastrointestinal surgery in high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries: a prospective, international, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2018;18:516–25. 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30101-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Danwang C, Mazou TN, Tochie JN, et al. . Global prevalence and incidence of surgical site infections after appendectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020101–e01. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. . Meta-Analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (moose) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008–12. 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. . The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700–b00. 10.1136/bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, et al. . Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:934–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Barendregt JJ, Doi SA, Lee YY, et al. . Meta-Analysis of prevalence. J Epidemiol Community Health 2013;67:974–8. 10.1136/jech-2013-203104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cochran WG. The combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics 1954;10:101–29. 10.2307/3001666 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Higgins JPT, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Viera AJ, Garrett JM. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med 2005;37:360–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, et al. . Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. WHO Global guidelines on the prevention of surgical site infection, 2016. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250680/9789241549882-eng.pdf?sequence=8 [Accessed 23 Nov 2019].

- 41. Sievert DM, Ricks P, Edwards JR, et al. . Antimicrobial-Resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections summary of data reported to the National healthcare safety network at the centers for disease control and prevention, 2009–2010. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2013;34:1–14. 10.1086/668770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Buggy D. Can anaesthetic management influence surgical-wound healing? Lancet 2000;356:355–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02523-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Seidell JC, Halberstadt J. The global burden of obesity and the challenges of prevention. Ann Nutr Metab 2015;66:7–12. 10.1159/000375143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Checkley W, Ghannem H, Irazola V, et al. . Management of ncd in low- and middle-income countries. Glob Heart 2014;9:431–43. 10.1016/j.gheart.2014.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Versporten A, Zarb P, Caniaux I, et al. . Antimicrobial consumption and resistance in adult hospital inpatients in 53 countries: results of an Internet-based global point prevalence survey. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:e619–29. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30186-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Klein EY, Van Boeckel TP, Martinez EM, et al. . Global increase and geographic convergence in antibiotic consumption between 2000 and 2015. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018;115:E3463–70. 10.1073/pnas.1717295115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Foster D, Kethman W, Cai LZ, et al. . Surgical site infections after appendectomy performed in low and middle human Development-Index countries: a systematic review. Surg Infect 2018;19:237–44. 10.1089/sur.2017.188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Marchi M, Pan A, Gagliotti C, et al. . The Italian national surgical site infection surveillance programme and its positive impact, 2009 to 2011. Euro Surveill 2014;19:20815 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2014.19.21.20815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Udwadia TE. Diagnostic laparoscopy. Surg Endosc 2004;18:6–10. 10.1007/s00464-002-8872-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Adisa AO, Lawal OO, Arowolo OA, et al. . Local adaptations aid establishment of laparoscopic surgery in a semiurban Nigerian Hospital. Surg Endosc 2013;27:390–3. 10.1007/s00464-012-2463-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Alfa-Wali M, Osaghae S. Practice, training and safety of laparoscopic surgery in low and middle-income countries. World J Gastrointest Surg 2017;9:13–18. 10.4240/wjgs.v9.i1.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Haley RW, Culver DH, White JW, et al. . The efficacy oe infection surveillance and control programs in preventing nosocomial infections in US hospitals. Am J Epidemiol 1985;121:182–205. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Harbarth S, Sax H, Gastmeier P. The preventable proportion of nosocomial infections: an overview of published reports. J Hosp Infect 2003;54:258–66. 10.1016/S0195-6701(03)00150-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Birgand G, Lepelletier D, Baron G, et al. . Agreement among healthcare professionals in ten European countries in diagnosing case-vignettes of surgical-site infections. PLoS One 2013;8:e68618–e18. 10.1371/journal.pone.0068618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-034266supp001.pdf (2MB, pdf)